DOI: 10.31038/SRR.2018115

Abstract

Introduction: septoplasty and turbinectomy are one of the most frequently performed surgical procedures in otolaryngology, with reduced morbidity and mortality. It is known that the use of nasal saline solution increases the nasal mucociliary clearance, reducing the accumulation of secretion. However, despite being widely used, studies evaluating its efficacy in septoplasty and lower turbinectomy postoperative are still lacking.

Objective: To prove the benefit of Maresis (0.9% isotonic solution spray) in septoplasty and lower turbinectomy postoperative.

Method: Randomized, parallel, controlled, single-blind, single-center study, held at the IPO (Instituto Paranaense de Otorrinolaringologia), in which 106 patients underwent septoplasty and bilateral lower turbinectomy, divided into 2 groups (with and without application of Maresis) and compared objectively regarding the improvement in breathing, degree of mucosal edema, crusting and ease of crusts removal in the third and tenth day after surgery. Subjective evaluation regarding the obstruction, crusting and difficulty to sleep was also performed.

Results: The product shows a statistically significant result regarding the parameter ease of crusts removal and improved quality of sleep. Statistically significant differences for mucosal edema reduction and crusting were not observed between the two groups.

Conclusion: the use of Maresis® as an adjuvant in the treatment of immediate septoplasty and bilateral lower turbinectomy postoperative assists in the process of crusts removal and improving the quality of sleep in postoperative.

Key words

nasal spray. septoplasty. turbinectomy. post – operative. Nasal isotonic solution.

Introduction

Septoplasty and turbinectomy are one of the most frequently performed surgical procedures in otorhinolaryngology practice, with reduced morbidity and mortality [1].

The use of buffering in nasal surgeries used to be indicated for the prevention of the onset of bleeding, septal hematoma or synechia in postoperative, ensuring the coaptation of mucoperichondrium retail and cartilage stabilization2. However, it is known that its use presents possible complications, among the most common pain and discomfort in postoperative. In addition, the nasal buffering may cause hypoxia, oropharyngeal irritation, headache, crusting, synechia and secondary infection and is associated with a higher retention rate in the hospital and pain in postoperative. The nasal buffering is being less indicated routinely in postoperative for septoplasty and lower turbinectomy, since it has no proven benefit and increases the morbidity [2]. An alternative to this practice is the use of the transseptal suture, which presents a lower risk of complications [3–5].

It is expected that the patient’s recovery is as short and comfortable as possible, and any method that reduces surgical time and bring more comfort to the patient must be encouraged [5,6].

The most commonly post-operative treatments used include a combination of oral and local antibiotics, oral or local antihistamines with or without decongestants, oral and intranasal corticosteroids, and nasal rinsing with saline, isotonic or hypertonic solutions, as well as mucolytics and sympathomimetics. Adjuvant therapy aims to normalize the permeability of ostiomeatal complex by reducing the mucosal edema and promoting improved mucociliary system function [7].

Intranasal saline solutions have been used for clinical treatment of chronic rhinitis, sinusitis and post-operative care. Benefits include cleaning of nasal mucus, purulent secretions, cellular debris and crusts as well as the possibility of reducing the risk of synechia by cleaning the postoperative clots. Nasal wash cleans the upper airways and is a more conservative treatment as it has no adverse effects, it is the simplest of all, being cost-effective. In addition to removing the secretions, increases aeration of the nasal mucosa, leading to decreased local inflammation [8–11].

Maresis is a continuous jet nasal spray with a sterile sodium chloride isotonic solution, without vasoconstrictor and preservative-free. It does not alter the physiology of nasal mucosa cells and sinuses. It acts fluidizing the secretion of the nasal mucosa, favoring its removal, assisting in the treatment of nasal symptoms common to colds and flu and other respiratory disorders such as rhinitis, sinusitis and postoperative nasal surgery.

It is known that the use of nasal saline solution increases the nasal mucociliary clearance, reducing the accumulation of secretion. However, despite being widely used in clinical practice, the number of studies evaluating its efficacy in septoplasty and lower turbinectomy postoperative is still limited.

Objective

To assess the benefit and safety of Maresis® use in septoplasty and bilateral lower turbinectomy postoperative.

Methods

A phase IV, single-center, randomized, parallel, single-blind and controlled clinical trial held in IPO hospital between July 2014 and May 2015. Approved by the institution´s ethics and research committee.

It was based on the choice of patients referred for septoplasty and turbinectomy by nasal obstruction, operated under local anesthesia for the same surgical technique by three different surgeons belonging to the same team. Patients were randomized in two groups, with Maresis® (test group) or without (control group) and were evaluated in the postoperative period.

All patients met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and signed the Informed Consent Form before entering the study.

Inclusion criteria included age between 18 and 65 years; indication for septoplasty and bilateral lower turbinectomy with turbinate luxation; agreement to meet the requirements of the trial and attend the institute in the day(s) and time(s) defined for evaluations.

Exclusion criteria were the use of other nasal decongestant; use of analgesic and corticosteroid not described in the protocol; hypersensitivity to components of the formula; use of nasal topical medications; pregnant and lactating women; alcohol intake during treatment; associated surgery; use of Gelfoan; buffering and splint; patients who underwent surgery under general anesthesia and occurrence of post-operative complications (septal hematoma, heavy bleeding requiring buffering or return to the operating room or infection).

The withdrawal criteria were loss of follow up; loss, damage and/or misdirection of the sample causing discontinuation of use by the volunteer, adverse event preventing the continued use of the product being studied.

At the time of hospital discharge, subjects were randomized in two groups, with name, age and sex registries. In the test group, the patients used Maresis® six times a day, associated with the oral drugs, which included the use of acetaminophen 500 mg and pseudoephedrine hydrochloride 30 mg – every 8 hours for 3 days and prednisone 40 mg/day for 5 days. In the control group, only the oral drugs were administered.

The first return occurred after three days (ranging from two to four days). Patients were asked about the improvement of breathing until the third day and underwent a clinical evaluation performed by a blinded researcher physician, with analysis of the degree of mucosal edema (absent or mild, and medium or severe), crusting (absent or present, only at the incision, in up to 50% of the septum or more than 50% of the septum) and ease of removal of crusts (very easy, easy, difficult, or indifferent). The patients answered a questionnaire grading nasal obstruction, crusting and difficulty to sleep.

The second return occurred ten days after (ranging from nine to eleven). The initial evaluation was repeated and patients again answered to the initial questionnaire and about the use of the study product .

It proceeded to statistical analysis. Quantitative variables were summarized by the number of valid observations, mean, standard deviation, median, quartile range, minimum and maximum. Qualitative variables were described using frequency tables, including absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies.

Superiority of Maresis ® associated with acetaminophen 500 mg and pseudoephedrine hydrochloride 30 mg + Prednisolone 40 mg compared to acetaminophen 500 mg associated to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride 30 mg + Prednisolone 40 mg was assumed if the 95% confidence interval lower limit calculated for the mean difference in clinical scale for improvement of obstruction and nasal crusting between the two treatments exceed the superiority margin δ =0,10.

The secondary endpoint, the difference in adverse events rate after 10 days of treatment was summarized by treatment group using data descriptive analysis. Expected treatment effect was provided together with confidence intervals, if applicable. If applicable, the descriptive p values for comparisons of the treatment groups were computed.

Other comparative analysis between Maresis® associated with acetaminophen 500 mg and pseudoephedrine hydrochloride 30 mg + Prednisolone 40 mg and acetaminophen 500 mg associated with pseudoephedrine hydrochloride 30 mg + Prednisolone 40 mg were made. Quantitative variables were compared using the T test for independent samples, or alternatively, the Mann-Whitney test, if not taken the assumption of distribution normality. Comparisons of qualitative variables were made using Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test.

All hypothesis tests were performed bilaterally, considering a significance level of 5%, i.e., statistical significance was set at p <0.05.

Results

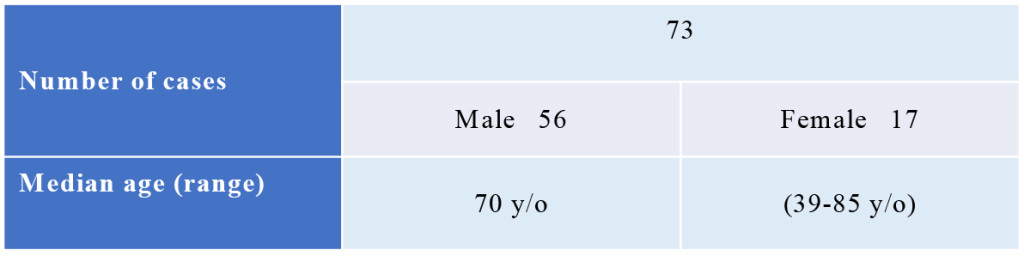

All of the 106 selected patients were randomized (53 in each treatment arm), but only 79 had their data validated for efficacy statistical analysis, totaling 45 patients in the test group and 34 in the control group.

The average age of study subjects was 31.04 ± 9.70 years in the test group and 33.44 ± 10.17 in the control group. No statistical differences were noted in gender, age and physical exams distribution (weight, height and BMI) between the two groups in the pre-treatment

(p > 0.05).

No statistical differences were observed between the clinical indications for the surgery in both groups. In both groups, all subjects had nasal obstruction as clinical indication for surgery; furthermore, 6.67% of the subjects in the test group had recurrent sinusitis and 4.4% had rhinogenic headache. The same symptoms were observed in 14.71% and 5.9% in the control group, respectively.

The efficacy of adding continuous jet nasal spray in postoperative was clinically evaluated according to three parameters: decreased mucosal edema, decreased crusting and ease of crusts removal. The results indicate that the product exhibits a statistically significant result on the parameter ease of crusts removal. No statistically significant differences were observed for reduced mucosal edema and crusting between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Variables assessed by physicians for all patients in the study between visit 1 and visit 2.

|

|

Intervention |

N |

Mean of difference |

Standard deviation |

Differences 95% confidence interval |

|

Regarding mucosal edema |

Maresis |

45 |

0.58 |

1.033 |

–0.404; 0.442 |

|

Control |

34 |

0.56 |

0.786 |

|

|

|

Regarding crusting, in which degree do you assess the current state of the patient? |

Maresis |

45 |

0.31 |

0.763 |

–0.547; 0.169 |

|

Control |

34 |

0.50 |

0.826 |

|

|

|

Regarding ease of crust removal, how do you assess the current state of the patient? |

Maresis |

45 |

0.78 |

1.259 |

0.291; 1.500 |

|

Control |

34 |

-0.12 |

1.387 |

|

* 95% Confidence Interval for mean differences of independent samples.

Three days after surgery, 37% of subjects in the test group did not present any difficulty to sleep versus 8.8% in the control group; furthermore, 20.6% of subjects in the control group reported great difficulty to sleep, while only 8.9% of those in the test group reported the same. These figures show that the test use in postoperative for septoplasty and turbinectomy improves ease into sleep (p <0.005). For the remaining parameters assessed by patients no statistically significant differences were observed. This perceived improvement was not maintained after 10 days of treatment (Tables 2 and 3). Ten days after surgery the evaluations were homogeneous between the groups (Table 2 and 3).

Table 2. Clinical variables of interest assessed by patients for all patients in the study in visit 1 (3 days after surgery).

|

|

Intervention |

N |

p value |

|

How quickly could you breathe better after surgery? |

Maresis |

45 |

0.054 |

|

Control |

34 |

|

|

|

How do you rate nose obstruction (blockage)? |

Maresis |

45 |

0.453 |

|

Control |

34 |

|

|

|

How do you rate crusting in the nose? |

Maresis |

45 |

0.109 |

|

Control |

34 |

|

|

|

Did you have difficulty to sleep? |

Maresis |

45 |

0.039 |

|

Control |

|

|

* Chi-Square Test, Yates correction and Fisher’s test for comparison of independent samples proportions.

Table 3. Clinical variables of interest assessed by patients for all patients in the study in visit 2 (10 days after surgery).

|

|

Intervention |

N |

p value |

|

How quickly could you breathe better after surgery? |

Maresis |

45 |

0.936 |

|

Control |

34 |

|

|

|

How do you rate nose obstruction (blockage)? |

Maresis |

45 |

0.839 |

|

Control |

34 |

|

|

|

How do you rate crusting in the nose? |

Maresis |

45 |

0.213 |

|

Control |

34 |

|

|

|

Did you have difficulty to sleep? |

Maresis |

45 |

0.129 |

|

Control |

34 |

|

* Chi-Square Test, Yates correction and Fisher’s test for comparison of independent samples proportions.

After 10 days of treatment, subjects in the test group assessed the degree of satisfaction with the product. Ninety-one percent of subjects were satisfied or very satisfied with the use of Maresis®; 100% of subjects considered the product as easy or very easy to apply and 93.3% would indicate the product.

To evaluate the safety of Maresis® use, information from the 106 randomized volunteers were considered. No serious adverse events were reported during the study. Ten adverse events were reported in the study, none of them related to Maresis®. According to the results, the addition of Maresis® to postoperative therapy did not lead to increased adverse events (p = 1.00).

Discussion

The positive results found in this study may be related to the amount of volume dispensed by Maresis®, as well as the technology of its nasal applicators, promoting adequate washing in patients’ nasal cavities.

The use of nasal isotonic saline solution is a simple and low cost procedure, which has been used for years to treat sinonasal tract diseases. Its use causes relief in signs and symptoms of these conditions, reduces the use of drugs and may help to minimize antimicrobial resistance [12].

Its use has proved to be well tolerated in patients with allergic rhinitis, leading to improvement of symptoms and must even be considered as adjuvant therapy to maintain the efficacy of nasal corticosteroid therapy at reduced doses, thus reducing the occurrence of possible side effects and the cost [13].

Pynnomen14 assessed the use of saline solution nasal spray and irrigation with higher amounts of saline solution with slight positive pressure in 127 patients with sinonasal symptoms, demonstrating that there is a greater improvement in symptoms with the use of nasal irrigation.

Frequently, topical saline solution has been prescribed, empirically, to lessen patients’ discomfort in nasal surgery postoperative. It is hypothesized that these sprays may perform such benefits by reducing mucus, clots, mucosal edema, and reduction in inflammatory mediators. Many studies refer to the importance of nasal rinsing with saline solution in improving the permeability and mucociliary clearance in clinical diseases [9–11]. However, despite the widespread use, there are still few studies demonstrating which solution works best and the advantages in the postoperative period, and, therefore, there is no conduct standardization.

Pinto15 analyzed the use of nasal spray on symptoms of nasal obstruction, secretion, headache and difficulty to sleep in postoperative endoscopic surgery. There was no evidence of benefit from the use of nasal sprays. This study differs from ours in which the ease in the removal of crusts and improvement in quality of sleep were statistically significant with the use of continuous jet spray.

Besides removing the secretions and crusts, nasal irrigation increases aeration of nasal mucosa, leading to reduction of local inflammation. Therefore, it improves the quality of life, as it reduces the accumulation of secretions resulting in symptoms of anterior and posterior rhinorrhea, and increases the air flow which was reduced due to these secretions [8,9,11]. Thus, it has preventive function of humidification and cleaning of airways from bacteria, allergens and irritants, favoring mucociliary clearance, providing comfort to the patient.

Conclusion

The results of the study indicate that the use of Maresis® as an adjunct in the treatment of immediate postoperative for septoplasty and bilateral lower turbinectomy assists in crusts removal process and improves patients’ quality of sleep. The addition of Maresis® to standard postoperative therapy is safe.

References

- Haroon Y; Saleh HA; Abou-Issa AH. (2013) Nasal soft tissue obstruction improvement after septoplasty without turbinectomy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 270(10): 2649–55. [Crossref]

- Bernardo MT; Alves S; Lima NB; Helena D; Condé A. (2013) Septoplasty with or without postoperative nasal packing? Prospective study. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 79(4): 471–4. [Crossref]

- Thapa N; Pradhan B. (2011) Postoperative complications of septal quilting and BIPP packing following septoplasty. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 9(2): 186–8. [Crossref]

- Ghimire A; Limbu TR; Bhandari R. (2012) Trans-septal suturing following septoplasty: an alternative for nasal packing. Nepal Med Coll J. 14(3): 165–8. [Crossref]

- Yildirim G; Cingi C; Kaya E. (2013) Septal stapler use during septum surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 270(3): 939–43. [Crossref]

- Quinn JG; Bonaparte JP; Kilty SJ. (2013) Postoperative management in the prevention of complications after septoplasty: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 123(6): 1328–33. [Crossref]

- Aukema AAC, Fokkens WJ. (2004) Chronic rhinosinusitis: management for optimal outcomes. Treat Respir Med. 3(2): 97–105. [Crossref]

- Olson DE, Rasgon BM, Hilsinger RL. (2002) Radiographic comparison of three methods for nasal saline irrigation. Laryngoscope. 112: 1394–8. [Crossref]

- Hauptman G; Ryan M.W. (2007) The effect of saline solutions on nasal patency and mucociliary clearance in rhinosinusitis patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 137(5): 815–21. [Crossref]

- Ural, A; Oktemer, T.K; Kizil, Y; Ileri, F; Uslu, S.J. (2009) Impact of isotonic and hypertonic saline solutions on mucociliary activity in various nasal pathologies: clinical study. Laryngol Otol. 123(5): 517–21. [Crossref]

- Jurkiewicz, D; Rapiejko, P. (2011) Use of isotonic NaCl solution in patients with acute rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Pol. 65(1): 47–53. [Crossref]

- Papsin B, McTavish A. (2003) Saline Nasal Irrigation. Can Fam Physician. 48: 168–73.

- Chen JR, Jin L, Li X. (2014) The effectiveness of nasal saline irrigation (seawater) in treatment of allergic rhinitis in children. Int J Ped Otolaryngol. 78: 115–8. [Crossref]

- Pynnomen MA; Mukerji SS, Kim M, Adams E, Terrel JE. (2007) Nasal Saline for Chronic Sinonasal Symptoms. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 133(11): 1115–20. [Crossref]

- Pinto, J.M.;Elwany, S;Baroody, F.M.;Naclerio, R. (2006) Effects of saline sprays on symptoms after endoscopic sinus surgery. American Journal of Rhinology. 20(2): 191–196. [Crossref]

- Süslü, N; Bajin, M.D; Süslü, A.E; Oğretmenoğlu, O. (2009) Effects of buffered 2.3%, buffered 0.9%, and non-buffered 0.9% irrigation solutions on nasal mucosa after septoplasty. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol . 266(5): 685–9. [Crossref]