DOI: 10.31038/AWHC.2025811

Abstract

Background: Skilled birth attendant delivery is vital for the health of mothers and newborns, as most maternal and newborn deaths occur at the time of childbirth. Skilled delivery care service utilization in Ethiopia is still far-below any acceptable standards. However, Ethiopia still falls considerably below acceptable standards in providing skilled birth care services. Moreover, there is limited evidence regarding geographical distribution, and factors influencing access to skilled birth care services.

Objectives: The aim of this study is to assess magnitude, spatio-temporal variations and determinants of skilled birth attendant delivery among reproductive age women in Ethiopia between Demographic and Health Survey 2016 and 2019.

Design: Survey-based cross-sectional study design was employed for EDHS.

Setting: Data for both EDHS were collected in all nine regions and two city administrations of Ethiopia in 2016 and 2019.

Participants: The source population for this study was all fertile women of reproductive age in Ethiopia and the study population was all reproductive age women who gave birth in the last 5 years preceding each survey year in selected enumeration areas.

Outcome measure: Skilled birth attendant delivery was the outcome variable for this study.

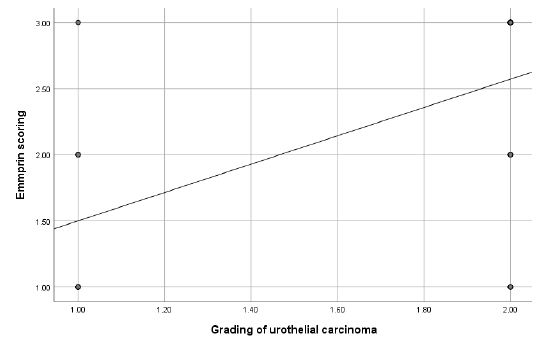

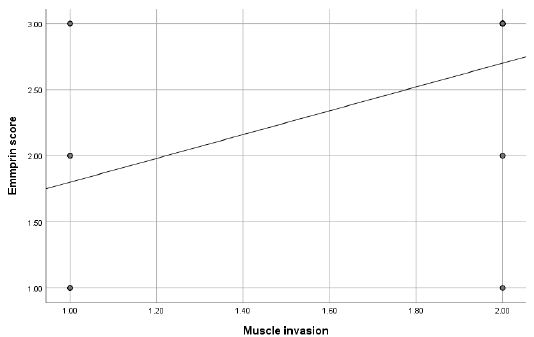

Results: Skilled birth attendant delivery utilization was increased from 27.7% in 2016 to 49.6% in 2019. The spatial pattern of skilled birth attendant delivery was non-random across the country and its distribution varied across regions. The spatial scan stastics analysis detected a total of 56 clusters (relative risk (RR)=3.12, p-value<0.01) in 2016 and 28 clusters (relative risk (RR)=2.02, p-value<0.01) in 2019 significant most likely (primary) clusters. Maternal education, parity, household wealth index, ever use of family planning, media exposure, health insurance coverage, maternal age at first birth, distance from health facility, type of place of residence, region, community child care burden and community poverty level were significant determinants.

Conclusion: Skilled birth attendant delivery remains far-below national acceptable standards and had significant spatial variation across the country. Individual-level and community-level factors were associated with skilled birth attendant delivery. Therefore, a geographic specific intervention should be launched by the government and respective local administrators supported by small area researches done by academia in regions with low skilled birth attendant delivery, to intensify individual and aggregated community level variables.

Keywords

Skilled birth attendant delivery, Spatio-temporal variation, Multilevel analysis, Ethiopia

Introduction

In 2015, an estimated 303, 000 women died during pregnancy and childbirth. One woman in 41 in low-income countries died from maternal causes. In 2016, maternal mortality as the second leading cause of death for 15-49 age women. Most maternal deaths (95%) happened in low and lower middle income countries, and About 65% death recorded in African countries. Worldwide, about 295,000 maternal deaths occurred in 2017 which is 38% of decreament from the year 2000 with an average decreament of 3% each year. Even though a significant decline was recorded in the last 25 years, still the death of reproducive age women is high. Approximately 810 women perished per day from avoidable pregnancy and childbirth-related causes, which is the vast majority of these deaths (94%) that occurred in low-resource setting countries. Maternal mortality ratios dropped globally from 385 per 100,000 new births in 1990 to 216 in 2015. Despite this global decrement, there is still high rates of maternal death in Africa’s sub-Saharan region and South Asia; which accounts for 88% of worldwide maternal death. In spite of tremendous progress made on maternal health at the global level with the implementation of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), there is slower progress in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Ethiopia’s maternal mortality rate decreased by 71.8% between 1990 and 2015, from 1250 deaths per 100,000 livebirths to 353, which is less than the goal of the maternal mortality-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). In Ethiopia, maternal mortality ratio declines from 676 every 100,000 live births in 2011 to 412 every 100,000 live births in 2016. Despite this decrement, the plan of reducing the maternal mortality ratio to 199 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births by 2020 was unachieve [1-8].

In the year 2000, The United Nations (UN) Millennium Declaration set eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for its member states to reach by 2015. One of these goals was to cut the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) by 75% (MDG-5). In the event that the MMR is not reduced by 2015, the worldwide community reviewed the goals and redeveloped them as 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). One of these SDGs is to cut MMR globally to less than 70 by 2030 [2]. Maternal mortality reduction remains a priority agenda under goal three in the UN Goals for Sustainable Development (SDGs) through 2030. one of the best ways to achieve this objective is through providing skilled care during delivery [1,9]. Skilled birth attendance Through the prevention or treatment of the majority of obstetric complications, the labour, delivery, and early postpartum period can dramatically lower mother and newborn morbidity and mortality complications. Ending preventable maternal death remain at the top of the global agenda [10,11].

In recent decades, the world has made significant progress reducing new born and maternal deaths. Between 1990 and 2020, the new born mortality rate was almost halved. However, the number of women and new-borns dying is still unacceptably high, primarily due to treatable or preventable conditions such infectious illnesses and pregnancy-related problems or childbirth. In Sub-saharan Africa one in every two deliveries occurs outside of a health facility and without skilled assistant care. In Sub-Saharan Africa, childbearing women face a 1 in 39 risks of dying in childbirth [12-14]. In addition to indirect reasons including anaemia, malaria, and heart disease, the most frequent direct causes of maternal injury and death are excessive blood loss, infection, high blood pressure, botched abortion, and obstructed labour [11].

The majority of maternal deaths can be avoided with prompt intervention by a qualified healthcare provider operating in a nurturing environment [11]. Reducing maternal mortality is the target of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.1, and achieving this goal is thought to depend on skilled attendance at birth. If a woman receives care from qualified medical professionals, many maternal deaths can be avoided. In childbearing, women need a continuum of care to ensure the best possible health outcome for them and their new born. The skilled attendant is at the centre of the continuum of care [15].

Skilled care referred to as when a woman and her child receive care during pregnancy, childbirth, and the immediate postpartum period from a licenced and qualified healthcare professional who has access to the required tools and the backing of an operational healthcare system-including transportation and facilities for emergency obstetric care. An skilled birth attendant is defined as “an accredited health professional such as a midwife, doctor or nurse who has been educated and trained to proficiency in the skills needed to manage normal (uncomplicated) pregnancies, childbirth and the immediate postnatal period, and in the identification, management and referral of complications in women and new born” [16].

Skilled birth attendant delivery refers to births delivered with the assistance of either doctors, nurses, midwives, health officers or health extension workers [17].

According to studies, the percentage of women using trained health professionals to give birth has increased slightly over the past 20 years across all regions and as a result, the global rate of births attended by skilled health professionals has increased significantly from 64% in 2000 to 83% in 2020. Just 80% of live births worldwide between 2012 and 2017 took place in medical facilities with the assistance of skilled birth attndants. Globally, 70% of births in rural areas and 90% of births in cities worldwide are attended by skilled birth attndants. Sub-Saharan Africa shows the biggest differences, with 49% of rural births and 81% of urban births in Western and Central Africa being attended by trained medical professionals. But in Sub-Saharan Africa, where maternal mortality is highest, only 59% of live births were attended by trained health personnel. Despite the fact that competent prenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care can save women’s lives, in Ethiopia, 28% of births in 2016 and 50% of births in 2019 were attended by qualified professionals, which is unacceptable high [18,19].

Approximately 73% of all maternal deaths resulted from direct obstetric cases, while 27% were caused by indirect factors. Approximately 25% of maternal fatalities happened during the prepartum phase, followed by 25% during the intrapartum and immediate postpartum phases, 33% during the sub-acute and delayed postpartum phases, and 12% during the late postpartum phase [20,21].

Evidences from different studies indicated that women’s age at first birth, household wealth index, participation in household decisions, mother’s/father’s education, health insurance coverage, religion, frequency of ANC visit, knowledge of critical pregnancy and delivery danger signs, parity, ANC visit, media exposure, History of still birth, Maternal occupation, place residence, geopolitical region, perception of distance from the health facility and community childcare burden were factors of skilled birth attendant delivery [22-29].

Numerous small-scale research on skilled birth attendance delivery utilizations have been conducted at the regional and lower administrative levels of the country, But at the national level little was done on the spatio – temporal patterns of skilled birth attendant delivery and associated factors after EDHS year 2016. Moreover, the trend of skilled birth attendant utlization from EDHS year 2016 upto 2019 not well known. Therefore, this study attempts to fill these evedence gap by investigating the spatial and temporal varation of SBA delivery and its associated factors using multilevel model analysis using EDHS survey 2016 and 2019 data.

Methods and Materials

Study Design, Setting and Period

For this investigation, cross-sectional survey data from two EDHS (2016 and 2019) were utilised. At the national level, complete surveys were carried out every five years, with micro surveys in between. The study was conduct in Ethiopia, which is a developing country, whose economy is mainly dependent on agriculture. Ethiopia is found throughout the Horn of Africa and shares a border with Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan and Kenya. (3°–14° N and 33°–48° E) is where it is. Administratively, it is divided into two city administrations (Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa) and nine regions (Afar, Amhara, Benishangul-Gumuz, Gambelia, Harari, Oromia, Somali, Southern Nations Nationalities and People’s Region (SNNPR), and Tigray) and further divided into Zones, districts, towns, and kebeles.

Source and Study Population

Every fertile woman in reproductive age in Ethiopia were the study’s source population and all reproductive age women who gave birth in the last 5 years preceding each survey year in selected enumeration areas were study population.

Sample Size & Sampling Procedures

A total of 16,394 reproductive age women, who had a live birth five years prior to the study were included in this study. The study included the two city administrations as well as all nine regions in Ethiopia. A stratified two-stage cluster sampling procedure was used to select the nationally representative sample in both surveys, with a high overall response rate that ranged from 98% to 99%. In the first stage, total EAs (in urban and rural) were chosen independently in each sampling stratum and with a probability corresponding to the size of the enumeration area. In the second stage, a set number of households per cluster were chosen using an equal probability systematic selection process. For spatial analysis, a total of 624 clusters in 2016 and 305 clusters in 2019 were used after removing clusters with zero coordinates. The entire sampling technique were available in both survey year report [17,30].

Data Collection Tools and Procedures

Face-to-face interviews with structured questionnaires were used to gather EDHS data. For this analysis, the data were taken from the measure DHS programme (Demographic and Health Survey) website (www.measuredhsprogram.com), after gaining permission for download and additional analysis on Nov 30, 2022. Similarly location information (longitudinal and latitude) was extracted from the downloaded GPS (Global Positioning System) file. Data extraction was performed using STATA version 12. After extraction, observations with in cluster of having zero latitude and longitude were left out for spatial analysis.

Variables

Dependent Variable

Skilled birth attendant delivery was the outcome variable for this study and it was coded as 1 if the woman received assistance during delivery from competent delivery attendants and 0 otherwise.

Independent Variables

Socio-demographic and socio-economic variables (maternal age, religion, household wealth index, mother’s education, mother’s occupation and health insurance coverage), Obstetrics related variables (parity, ever use of family planning and age of Mather at birth) and community-level variables (region, place of residence, community poverty level, distance from health facility and community level childcare burden). For this study community poverty level and community child care burden variables were computed by adding up all of individual level variables within their clusters by utilising the median values of the percentage of women in each category of a given variable, since not all aggregates were normally distributed.

Data Management and Analysis

Following, extracting the EDHS data; STATA version 12 and Microsoft Excel was used for editing, cleaning and recoding. Prior to analysis, the data was weighted using sampling weight to ensure that the survey was representative again and to instruct STATA to use the sampling design when calculating standard errors to produce accurate statistical estimates. The joining variable was used to combine the datasets to the Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates of the EDHS clusters.

Spatial Analysis

The spatial analysis was carried out using Arc-GIS 10. 7 and Sat Scan 9.6. A cross tabulation was performed using the result variable’s weighted frequency and cluster number in STATA software and exported to excel to get the case to total proportion. Then excel file was imported to Arc-GIS 10.7 for spatial analysis and joined to the geographic coordinates based on each cluster unique identification code. The units of spatial analysis were DHS clusters (geographic coordinates of EDHS were collected at cluster level). The Ethiopian Poly-conic Projected Coordinate System was utilised to create the map of Ethiopia.

Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

Global spatial autocorrelation was measured with Arc-GIS using the Global Moran’s-I statistics to determine whether the pattern expressed is clustered, scattered, or random throughout the study areas. Moran’s I is a spatial statistics that measures spatial autocorrelation by yielding a single output value between -1 and +1. Moran’s I Values close to −1 indicate disease/intervention is dispersed, whereas moron’s I close to +1 indicate disease clustered and disease distributed randomly if I value is zero. The presence of spatial autocorrelation is indicated by a statistically significant Moran’s I (p < 0.05), which leads to the rejection of the null hypothesis (skilled birth attendance is randomly distributed). Local Anselin Moran’s In terms of positively connected (high-high and low-low) or negatively correlated (high-low and low-high) clusters, used to look into the local level cluster locations of skilled birth attendance. A positive value for ‘I’ indicated that a case with adjacent cases that had similar values. A negative value for “I” indicated that a case was surrounded by cases that had values that were different from its own.

Host Spot Analysis (Getis-Ord Gi* Statistic)

The Getis-Ord Gi* statistic was calculated to quantify how spatial autocorrelation varied over the research location. The statistical significance of the clustering was assessed using the Z-score and the p-value. Spatial clusters with high values (hot spots) and low values (cold spots) were distinguished by the Getis-Ord Gi* statistic. Gi* is a measure of local autocorrelation, i.e. it measures how spatial autocorrelation varies locally over an area and provide statistic for each data points. If z-score is higher, the intensity of the clustering is stronger. A z-score that is close to zero denotes no clustering, a positive z-score suggests high value clustering, and a negative z-score suggests low value clustering.

Spatial Interpolation

Spatial interpolation is the process of estimating values (spatially continuous variables) for spatial locations which have not value from spatial location using known values. It is the method of determining the unknown value for any given set of points with known values. Spatial interpolation technique was used to predict SBA delivery on the un-sampled areas in the country based on sampled EAs. Numerous deterministic and geo-statistical interpolation techniques exist. Ordinary Kriging and empirical Bayesian Kriging are regarded as the best techniques out of all of them since they statistically optimise the weight and take into account spatial autocorrelation. For this study, the Ordinary Kriging spatial interpolation approach was employed to forecast SBA delivery in Ethiopian regions that were not sampled.

Spatial Scan Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis using Sat Scan version 9.6, a Bernoulli-based model was used to determine whether statistically significant spatial clusters of SBA delivery were present or not. The spatial scan statistic uses a circular scanning window that moves across the study area. To suit the Bernoulli model, women who gave delivery with a skilled birth attendant were classified as cases, and those who did not were classified as controls. Each location’s case count followed a Bernoulli distribution, and the model needed information on cases, controls, and geographic coordinates. The number of observed SBA inside each probable cluster was compared to the expected number using the likelihood ratio test statistic and p-value to see if there was a significant difference. By comparing the rank of the maximum likelihood from the real data with the maximum likelihood from the random datasets, Monte Carlo hypothesis testing was used to assign a p-value to each cluster. The scanning window with the largest likelihood was the most likely performing cluster. Based on Monte Carlo replications, the primary and secondary clusters were found, given p-values, and ranked according to their likelihood ratio tests [31].

Multi-Level Analysis

The multi-level mixed effect logistic regression model was employed for the proper determinant estimate due to the hierarchical nature of the DHS data. Two-level multilevel Multivariable logistic regression (mixed effect model) was used to analyse factors associated with SBA delivery at two levels, at individual and community (cluster) levels. Four models were built. The first model was an empty model without any explanatory variables, to calculate the degree of variance within the cluster on SBA delivery. The second model was adjusted with individual level variables; the third model was adjusted for community level variables while the fourth was fitted with both individual and community level variables simultaneously. ICC (Intra-class correlation), MOR (median odds ratio) and the difference across clusters were measured using PCV (proportional change in variance). The ICC is a measure of within cluster variation (i.e., the variation between individuals within the same cluster) [32]. MOR refers the median value of the odds ratio between the cluster at high risk and the cluster at reduced risk when two clusters are randomly selected [33]. In comparison to the null model, PCV calculates the overall variation in the multilevel model that is attributable to individual and community level influences. The formulas for these measurements are as follows;

𝐼𝐶𝐶=𝑐𝑙𝑢𝑠𝑡𝑒𝑟 𝑙𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑙 𝑣𝑎𝑟𝑖𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑒 / 𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑣𝑎𝑟𝑖𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑒: i.e. 𝐼𝐶𝐶=𝑣𝑖/ (𝑣𝑖+𝜋2/3) were VI=estimated variance in each model, which has been described elsewhere.

𝑀𝑂𝑅=(0.95√𝑣𝑧) (put reference) where vz=the variance at the cluster level

PCV=(Vn1−Vn2)/ Vn1; (put reference) where Vn1 is the neighbourhood variance in the empty model and Vn2 is the neighbourhood variance in the subsequent model. Models were compared, based on the log-likelihood ratio (LLR) and deviation. The model with the highest LLR and with lowest deviance was considered as a best fitted model. Variables in the multivariable multilevel logistic regression analysis were deemed statistically significant if their p-value was less than 0.05. Finding the Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) and its corresponding 95% confidence interval was used for identifying factors associated to SBA delivery. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was also used to test for multi-colinearity. There is multi-co linearity if variable have VIF>10 and tolerance< 0.1

Dissemination of the Finding

As part of a Master of Public Health (MPH) thesis, the findings of the study will be present and disseminated to the Bahir Dar University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, School public health, department of health system management and health economics. The findings will also be shared with the Regional health bureaus, and other relevant governmental and nongovernmental organizations. It will be submitted to scientific Journals for publication and possibly presented to other research conferences and seminars for concerned governmental and non-governmental organizations and stakeholders.

Results

Descriptive Characteristics of the Study Population

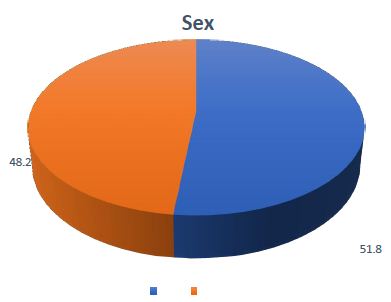

A weighted sample of 11,023 from EDHS 2016 and 5,527 from EMDHS 2019 reproductive age women were incorporated into this research. However, the data of 21 clusters from EDHS 2016 were not included in the spatial analysis as geographical information was missed. 66.1% of study participants in EDHS 2016 and 53.6% in EMDHSB2019 had no formal education. About 96.5% of the study participant’s health expenditure was not protected by health insurance in EDHS 2016. Regarding media exposure, about 81.9% of participants had no media exposure in EDHS 2016. The median age of participants upon first birth, was 18 years in both survey years. Large of study participants 88.9% and 75.3% were lived in rural area in EDHS 2016 and EMDHS 2019 respectively. From the total participants more than half, 56.6% in EDHS 2016 and 57.1% in EMDHS 2019 were lived in communities with low poverty level. The percentage of women delivery with the assistance skilled professional was 27.7% and 49.6% in 2016 and 2019 respectively.

Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Skilled Birth Attendant Delivery

The proportion of skilled birth attendant delivery across regions of Ethiopia was increased over survey periods in all regions, except in Addis Ababa.

The overall Skilled birth attendant delivery showed increasing pattern in the country between survey years (2016 to 2019).

Spatial autocorrelation analysis indicated that the distribution of skilled birth attendant delivery was non-random across the two survey periods. Using a global Moran’s I statistic value of (I=0.36, P-value <0.001, for EDHS 2016 and I=0.17, P-value<0.001, for EMDHS 2019). This test result shows the existence of significant global positive spatial autocorrelation. The geographical dispersion of skilled birth attendant delivery varies throughout geographical areas in both surveys. It, suggests that there is local clustering in the distribution of skilled delivery that needs to be further explained using local statistics.

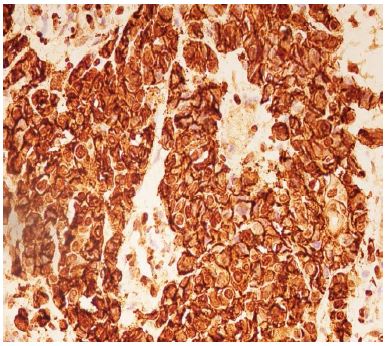

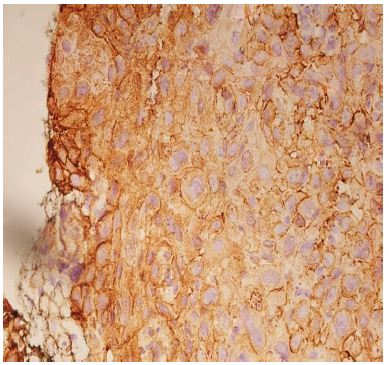

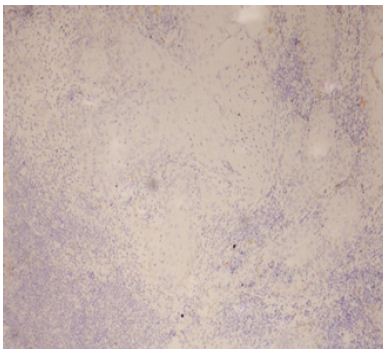

Hot Spot Analysis

The geographical distribution of SBA delivery was different in both survey periods. The Getis Ord Gi* statistical analysis identified the significant geographical distribution of hotspots and significant clustering of cold spots of SBA delivery. In EDHS 2016, hotspot of skilled birth attendant delivery was discovered in Dire Dawa, Harari, Addis Ababa, Northern part of SNNPR (Gurage) and Southern part of Amhara (north Shewa) regions. On the contrary, Afar, most part of Amhara, Benshangul-Gumuz, Western Gambela (Nuer), Central Oromia, SNNPR and Somali were regions with cold spots.

In EMDHS 2019, hotspot of SBA delivery was clustered in Dire Dawa, Addis Ababa, Harari and South west part of Benshangul-Gumuze (Asosa) regions; whereas Afar, Somali, Amhara and Eastern part of SNNPR were cold spot areas of SBA delivery. The overall spatial pattern of skilled birth attendant delivery was different across regions of Ethiopia over survey periods except Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa and Harari showed similar spatial pattern over the two survey years.

Spatial Interpolation

The spatial interpolation methods allow estimating values for locations where no samples have been taken and also used to assess the uncertainty of these estimates. We have used geo-statistical spatial interpolation with Ordinary Kriging technique in ArcGIS 10.7 software for estimating values for locations where no samples have been taken. From EDHS 2016, geo-statistical ordinary kriging analysis predicted that the highest frequency of skilled birth attendant delivery (77.7% to 98.5%) was discovered in Dire Dawa, Harari, Addis Ababa and south east part of Tigray. In contrast, area with relatively low prevalence (5.1%-15.5%) was predicted in Eastern part of Somali (Doolo), Southern Oromia (Borena and Guji), Western Gambela (Nuer), Benshagul (Metekel), Central Amhara (South Gondar) and Afar regions. Based on EDHS-2019 data, ordinary kriging analysis predicted that the prevalence of skilled birth attendant delivery was the highest percent about (79.09% to 98%) predicted in Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa, Harari and Western Benshangul-Gumuz (Asosa). In contrast, area with relatively low prevalence (13%-22.4%) was predicted in most part of Somali, southern Afar and south part of Oromia (Borena, Guji and Liben).

Spatial Scan Statistics

For detection of purely spatial clusters of SBA delivery, spatial analysis was carried out with the Culldorff spatial sat scan analysis. The circular window with highest likelihood ratio and containing more cases than expected was identified as the most likely (primary) cluster. A significance level of P < 0.05 was used to test whether the cluster was significant or not. A total of 13 significant clusters were found in the EDHS 2016. Of which, 1 was most likely (primary) cluster and 12 of them were secondary clusters. The primary cluster spatial window was found in Addis Ababa which was located at (8.977567 N, 38.738050 E) of geographic location with 14.56 km radius, as well as the Log-Likelihood ratio (LLR) of 441.312466 which was detected as the most likely cluster with maximum Likelihood. It demonstrated that women within this spatial window had 3.12 times more probable to deliver with SBAs than the women outside that area of the spatial window. The scanning window for the secondary clusters was found in Dire Dawa and Tigray, Northern SNNPR, Southern Gambela, Western Amhara and Western border of Oromia, with a LLR range from 9.7-441.3. In EMDHS 2019, A total of 9 significant cluster with p-value <0.05 were detected. 28 locations with overall sampled population of 337 were found as primary clusters. The spatial window of primary cluster was situated in Addis Ababa. The spatial window of primary cluster was located at (8.651588 N,39.118340 E) / 68.57 km in radius, with a log-likelihood ratio (LLR) of 181.62 and a relative risk (RR) of 2.02. It demonstrated that women within this spatial window had 2.02 times more probable to get SBA than the women outside areas of the spatial window. The location of the secondary cluster spatial window was in Dire Dawa, Benshangul, Tigray, South East and central Amhara, Eastern Afar, SNNPR and Eastern Gambela regions, with a log-likelihood ratio (LLR) of 9.6-181.6.

Determinant Factors of Skilled Birth Attendant Delivery

Intra-cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) in the empty model indicated that 16.8% and 36.7% of the overall fluctuation for skilled birth attendant delivery was caused by variations amongst clusters in EDHS 2016 and EMDHS 2019 respectively. The remaining unexplained (83.2% in EDHS 2016 and 63.3% in EMDHS 2019) was due to individual variations. The null model’s median odds ratio (MOR) was 2.8 and 3.8 in EDHS 2016 and EMDHS 2019 respectively. Which indicates in the event that two women are chosen at random from two distinct clusters, those in the cluster with the highest skilled birth attendant delivery had 2.8 and 3.8 times more likely to experience skilled birth attendant delivery as compared with women from the cluster that has a lower skilled birth attendant delivery utilization. Bi-variable logistic regression analysis was performed to find the variables for the multivariable multilevel logistic analysis. Variables with p-value <0.05 were taken into account for the multivariate study. Multi-collinearity was also checked using VIF, which was found with maximum value of 2.2 in EDHS 2016 and 2.1 in EMDHS 2019. It indicates that there was no multi-collinearity among independent variables. With the highest log-likelihood and the lowest deviation, the final model (model-4) was the best suited model.

Individual-Level Predictors

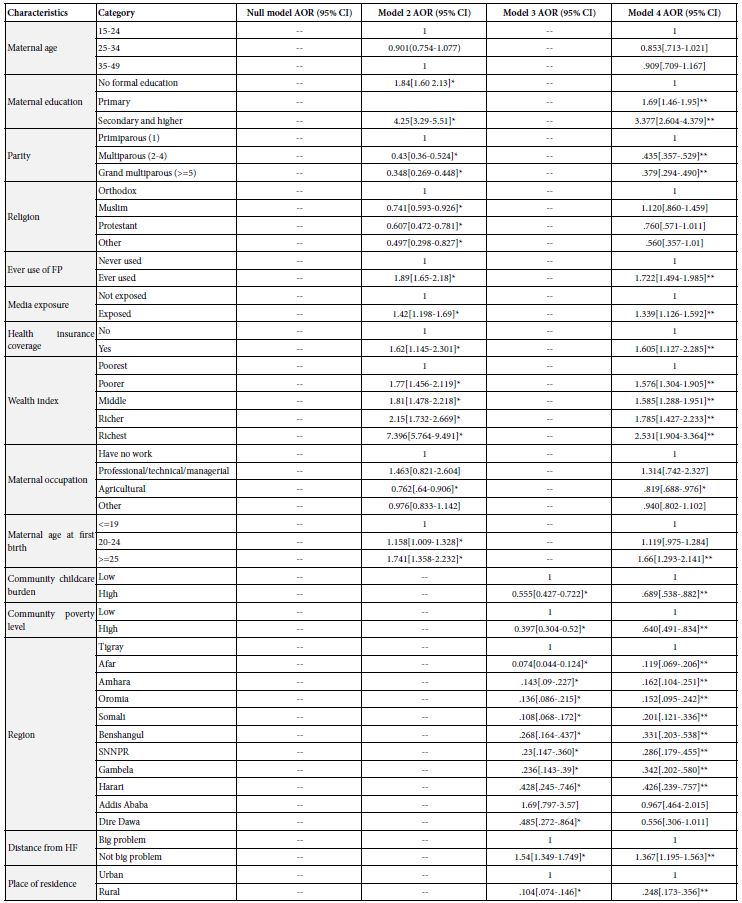

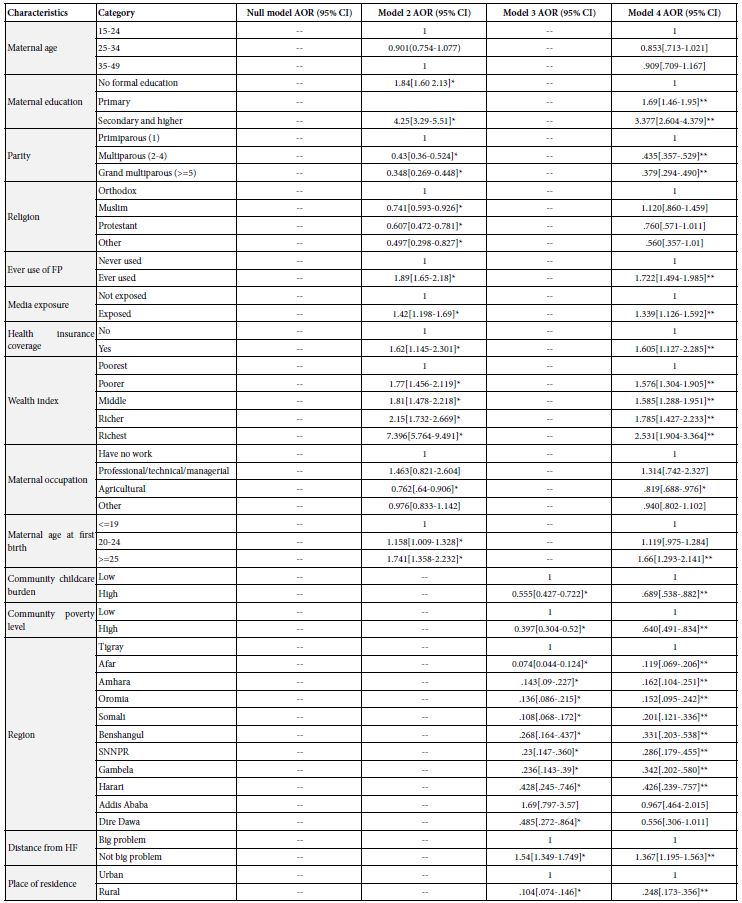

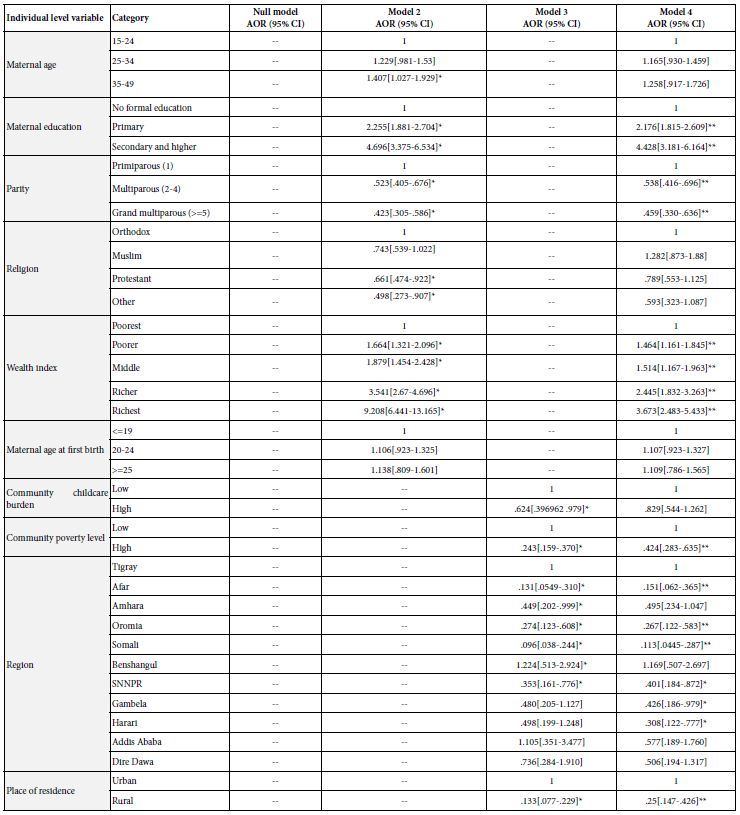

In multivariable multilevel mixed-effect logistic regression analysis; wealth index, maternal education level and parity were significantly linked to the delivery by skilled birth attendants in both survey periods, However, health insurance coverage, media exposure, ever use of family planning and maternal age at first birth was strongly correlated with the delivery by a skilled birth attendant in EDHS 2016 (Table 1).

Table 1: Multilevel logistic result of individual level and community level factors associated with SBA delivery in Ethiopia, EDHS 2016 regression analysis.

Key: 1: Reference group; *Significant with p-value 0.01-0.05; **Significant with p-value<0.01; — Not applied

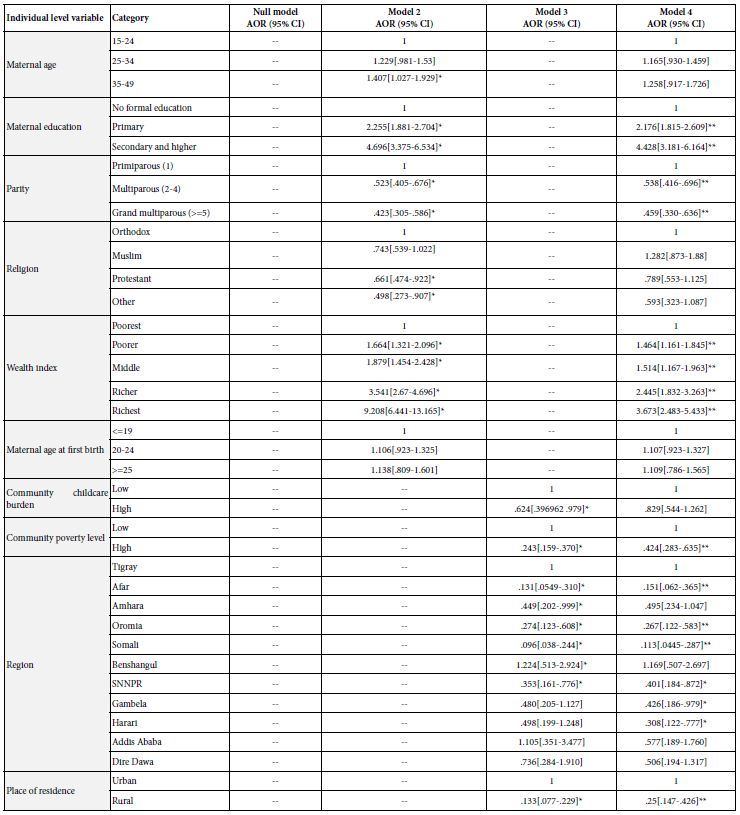

Table 2: Multilevel logistic regression analysis result of individual level and community level factors associated with SBA delivery in Ethiopia, EMDHS 2019.

Key: 1: Reference; *Significant with p-value 0.01-0.05; **Significant with p-value <0.01; — Not applicable

For variables showing significant association in both surveys, by taking the recent survey (EMDHS 2019), The likelihood of using SBA delivery for those women residing with household wealth index of poorer, middle, richer and richest increased with 1.46 times (AOR=1.46, 95%CI=1.16-1.85), 1.51 times (AOR=1.51, 95%CI=1.17-1.96), 2.44 times (AOR=2.44, 95%CI=1.83-3.26) and 3.67 times (AOR=3.67, 95%CI=2.48-5.43) respectively in contrast with women in poorest wealth index.

The likelihood of having SBA delivery for those women with primary education and those with secondary and higher were 2.18 times (AOR=2.18, 95% CI=1.82-2.61) and 4.43 times (AOR=4.43, 95%CI=3.18-6.17) higher as compared with no formal education respectively.

Women having 2-4 children and those who had 5 or above were 46.2% (AOR=0.538, 95% CI=0.42-0.69) and 54.1% (AOR=0.459, 95%CI=0.33-0.64) less likely to experience SBA delivery in contrast to those who had only one child respectively.

The likelihood of experiencing SBA delivery for those women reside in rural areas were lower by 75% (AOR=0.25, 95%CI=0.15-0.43) in contrast to those who live in urban areas.

The odds of experiencing SBA delivery for those women whose medical expenditure was covered by health insurance were 1.61 times (AOR=1.61, 95% CI=1.13-2.29) higher in contrast to those who don’t have health insurance.

The likelihood of having SBA delivery for those women who had media exposure were 1.34 times (AOR=1.34, 95% CI=1.13-2.29) higher compared to those who had no media exposure.

The likelihood of experiencing SBA delivery for those women who had ever used family planning were 1.72 times (AOR=1.72, 95% CI=1.49-1.99) higher compared to those who never used family planning.

The likelihood of having SBA delivery for those women with age at first birth was ≥25 years were 1.66 times (AOR=1.66, 95% CI=1.29-2.14) higher compared to those whose age at first birth was ≤19 years. But the proportion of women deliver with the assistance of SBAs with age at first birth between 20 and 24 had no significant difference with reference age of ≤19 years.

Community-Level Predictors

Multivariable multilevel mixed-effect logistic regression analysis showed that; region, type of location of the residence and community poverty level in both survey periods (2016 and 2019) and distance from health facility and community childcare burden only in EDHS 2016 were strongly linked to the delivery by a skilled birth attendant in EDHS 2016(Table 1 and 2).

For variables showing significant association in both surveys, by taking the recent survey (2019), The probability of women residing in Afar 84.9% (AOR=0.151, 95% CI=0.06-0.37), Oromia 73.3% (AOR=0.267, 95% CI=0.12-.58), Somalia 88.7% (AOR=0.113, 95% CI=0.045-0.29), SNNPR 59.9% (AOR=0.401, 95% CI=0.18-0.87), Gambela 57.4% (AOR=0.426, 95% CI=0.19-0.98) and Harari 69.2% (AOR=0.308, 95% CI=0.12-0.78) less likely to experience SBA delivery in contrast to those who live in Tigray region. Whereas, Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa, Amhara and Benshangul-Gumuz region had not changed all that much in proportion of SBA delivery from the region of reference Tigray.

The likelihood of having SBA delivery for those women reside in rural areas were lower by 75% (AOR=0.25, 95%CI=0.15-0.43) in contrast to those who live in urban areas.

Women who reside in areas with high rates of poverty in the community were 57.6% (AOR=0.424, 95%CI=0.28-0.64) less likely experiencing of SBA delivery in contrast t with those women live in a region with low rates of poverty.

The odds of experiencing SBA delivery for those women who perceive distance from health facility as not a big problem were 1.34 times (AOR=1.34, 95% CI=1.2-1.56) greater than those who perceive distance from health facility as a significant problem.

The probability of receiving SBA delivery for those women live with a community of high childcare burden were lower by 31.1% (AOR=0.689, 95%CI=0.54-0.88) as compared with low community childcare burden.

Discussion

This study was amid to explore spatio-temporal variation and determinants of SBA delivery among reproductive age women in Ethiopia over 3 years.

The finding of this study revealed that, the recent prevalence of SBA delivery was 49.6% (in EMDHS 2019). This finding is in consistent with previous study done in Kembata tambaro , Zone in Ethiopia 50.9% [28], whereas higher than study done in North west Ethiopia 18.8%, another study in Ethiopia 15.6% and Galkacyo district in Somalia 27%. This inequality may be because of the deference in study setting, sample size and period. In addition, it might be because of socio-demographic and cultural differences across regions. But this finding is lower than the result from Ghana 60.5%, Pooled prevalence in 12 East African Countries 67.18%, Rwanda 90.68%, Malawi 89.8%, Burundi 85.13%, Comoros 83.78, Zimbabwe 78.14%, Uganda 75.19%, Zambia 64.21%, Kenya 61.81% and Mozambique 53.65%. This may be as a result of the difference in accessing the service as well as due to the fact that women in those countries had better economic and educational status. This study showed that the delivery attended by skilled birth attendant increased from 27.7% to 49.6% between survey year 2016 and 2019. This improvement might be due to the focus of government since the inclusion of SBA as a key outcome indicator in the MDGs. In addition, some socio-demographic improvement in the country might contribute for the improvement of SBA delivery [35-39].

This finding revealed that the proportion of SBA delivery varies across the regions of the country. Studies conducted in developing countries also pointed out the significant regional variations in the use of SBA delivery [29,40]. This might be due to the socio-cultural and socioeconomic differences among regions of the country. The highest prevalence was observed in Addis Ababa (95.5%) and Tigray (73%), whereas the lowest prevalence was obtained in Afar (30.2%) and Somali (25.7%). This might be because of inequalities in the distribution of resources like skilled birth attendants. Moreover, women from pastoral regions might have limited access to information regarding maternal health services than those in agrarian and urban regions. Maternal health service utilization by pastoralists is extremely low because of lack of awareness, cultural beliefs, seasonal mobility and limited availability of health facilities and health staff [41].

Global Moran’s I value showed that spatial distribution of SBA delivery was non- random across the country and there was statistically significant clustering of SBA delivery. In this study significant cold spot areas of SBA delivery were observed in Afar, Amhara, Benshangul Gumuz, Gambelia, Oromia and Somali regions. One explanation could be the discrepancy in the provision of maternal health services, as well as the poor accessibility of infrastructure such as roads for transportation in those regions. Furthermore, the communities in these regions were more pastoral; as a consequence, relative to the rest, health facilities are not nearly available [41]. This finding shows that public health planners and programmers should develop successful public health actions to improve SBA delivery in these substantial cold spot regions.

Women from households of better economic status were more likely to use SBA during delivery in contrast to women raised from poorest household. This finding has also been demonstrated in similar studies in Ethiopia [29,35,40], Kenya [42], Nigeria [26], Ghana [23], India [43] and Bangladesh [44,45]. This might be due to the reason that women in a higher wealth index had greater autonomy in decision-making on reproductive health and more likely delivered under skilled birth attendance [46]. Women with better economic status often have the financial empowerment to access skilled attendance during delivery [47]. In contrast women in the poorest households are less likely to get health access because of economical constraint, which is backbone to get education and health services. Even though maternal health services in Ethiopia are free, this could not give a guaranty for the use of SBA delivery, because of the presence of other costs such as time and transportation. Sometimes mothers may be asked to buy supplies that are not available at the health facility at the time of delivery.

This study also indicated that women with increased education were more experiencing SBA delivery as compared with those not has formal education. This finding was consistent with studies conducted in Ethiopia [28,29,34,40,48], Kenya [42,49], Zambia [24], Nigeria [26], Bangladesh [22], Ghana [37] and east Africa [38]. This could be explained by the fact that women who are educated had knowledge about the delivery complication and their consequences on them and their child, which could push them to deliver with the help of SBAs. Educated women had more open and better communication with the husband, more decision-making power and better negotiating skills thus better ability to demand adequate services [50]. As a result, more emphasis is required in educating women specifically those with no formal education on the importance of skilled delivery services and its association with reduced maternal mortalities.

Those women whose health expenditure was covered by health insurance had higher odds of experiencing SBA delivery in contrast to those not have health insurance. This finding is in line with previous study done in Ethiopia [29] and Ghana [23]. This might be because of women’s health expenditure is covered by health insurance, they sense free and seek any medical care frequently and it might be narrows the difference between rich households and poor households in using SBA delivery service. This is supported by this study in which wealth index is a significant factor associated with SBA delivery.

The finding of this study indicated that women who exposed to media had more likely to use SBA delivery service as compared to those women who were not exposed to media. This finding was line with a previous study done in Ethiopia [35], Niger, Sierra Leone and Mali [27]. The possible reason is that health information may improve health-seeking habits, as information about what services are available, where and when to get them, as well as the benefits and risks of accessing specific services, can be communicated via different Medias.

Women with parity of more children were less likely to experience SBA delivery as compared with who had only one child. This finding was in line with previous studies in Ethiopia [29,38], Nigeria [26] and southern Ghana [51].This might be because women with higher parity might not have any complications before and take childbirth as a natural process or might have bad contact with a health professional previously, so they may prefer delivering without SBA [52]. Another possible explanation for this is that women who are pregnant with their first child are usually more likely to have difficulties during delivery than women of more parity. This may result in low parity women being more motivated to deliver with assistance of SBAs than women with more parity.

Women who had used any family planning services were more likely to deliver with the help of SBA in contrast to those women who had never used family planning. The finding is in agreement with studies conducted in Bangladesh [22]. Family planning service could empower women by exposing them to the health education about the benefit of skilled birth attendance. Moreover, women could understand the complication before, during and after delivery and early detection of complications arising during birth preparedness and complication planning which push them to visit skilled birth attendants.

The odds of experiencing SBA delivery for those women with age at first birth ≥25 year was higher as compared with those whose age at first birth was <=19 years. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in Bangladesh [22] and sub-Saharan Africa [53]. The possible reason for this finding could be the fear of stigmatization, devaluation and shaming young pregnant women to receive at maternal health services [54].

The odds of experiencing SBA delivery were lower among women who lived in Afar, Oromia, Somali, SNNPR, Gambelia, and Harari as compared to Tigray region. This finding indicated that SBA delivery vary across regions and in line with a study in Ethiopia [29] and Nigeria [26]. Regional variation in the health infrastructure can cause significant health service disparity. Another potential reason might be women in pastoral regions have poor access to education and are not permanent residents and because of these, there is limited availability and accessibility of maternal health services.

The likelihood of having SBA delivery for those women reside in rural was decreased by 75% compared to those women live in urban areas. The result was comparable with studies conducted in Kambata Tembaro Zone [28], North West Ethiopia [34,55], Ethiopia [29,40], Nigeria [26], East Africa [38] and Bangladesh [22]. Women living in urban areas have much easy access to skilled birth attendance compared to rural areas due to the proximity of the health facilities and better availability of transportation [56,57]. Another possible reason might be urban women in Ethiopia tend to benefit from increased knowledge and access to maternal health services compared with their rural counterparts, because, various health promotion programs uses urban-focused mass media work to the advantage of urban residents and explain the close connection between urban residence and use of maternal health services. Moreover, rural women are more readily influenced by traditional practices that are contrary to modern health care.

Women residing in communities with high poverty levels had lower odds to give birth by SBA as compared to women residing in communities with low poverty level. This finding is supported by a study done in Ethiopia [29, 35, 40], Bangladesh [22], India [43] and East Africa [38]. This is due to communities with high poverty level even might not be able to pay for health insurance and health insurance coverage is associated with SBA delivery in this study [58].

Women who perceive distance from health facilities as big problem were less likely to receive SBA delivery compared to those perceive distance from nearest health facility was not a big problem. The finding is also in agreement with studies conducted in Ethiopia [29,40]. This is due to the fact that long distance from health facilities is important factors to prevent mothers from seeking and utilizing skilled maternity care services. Moreover, some women at times deliver on the way to the health facility due to long distances [59,60].

Women who live in communities with high childcare burden had less likely to deliver with SBA as compared to those with low child care burden and this finding is in line with study in Ethiopia (29).This might be due to a high childcare burden may need cost and time for carrying children, which may prevent mothers from seeking and utilizing maternal health services like SBA delivery [61].

Conclusion

In spite of the above limitations, this study tries to explore spatio-temporal variation and determinants of SBA delivery among reproductive age women in Ethiopia. The magnitude of SBA delivery was lower in EDHS 2016 and it showed improvement in 2019. But if it continue with the current pace, it will be difficult to achieve the national Health Sector Transformation Plan II target. Despite the efforts that have been made in recent years to improve maternal health outcomes in Ethiopia, the proportion of women who receive assistance from SBAs is still unacceptably low.

The spatial pattern of SBA delivery in Ethiopia was clustered non-randomly across regions of Ethiopia. The most prominent low SBA delivery were detected in Afar, Amhara, SNNPR and Somali regions more or less consistently over survey periods. Benshangul-Gumuz, Gambela and Oromia showed improvements after survey year 2016. High proportion of SBA delivery was detected in Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa and Harari regions in both survey years.

Household wealth index, maternal birth, region, type of place of residence, community poverty level, distance from health facility and community child care burden were significant predictors of SBA delivery among reproductive age women.

Strengths and Limitations of This Study

Strengths of the Study

This study applied spatial pattern analysis tools and a multi-level mixed effect logistic regression model because of nested nature of the data. The study was used large dataset representing the whole regions of the country and applied sample weighting of data considering sample designs during analysis of cross-tabulation and estimation to be representative of the Ethiopian population.

Limitations of the Study

Since the study was a cross-sectional it doesn’t confirm a causal relationship between the independent and dependent variables. Respondents’ data with geographic coordinates didn’t specify were excluded for spatial analysis which could affect the generalizability of the findings. The DHS data depend on the respondent’s report, so there might be a recall bias.Moreover, medical and health facility related factors that might influence the outcome variable were not assessed.

Abbreviations

ANC: Antenatal care, ARC-GIS: Aeronautical Reconnaissance Coverage Geographic Information System, CMHS: College of Medicine and Health Sciences, CSA: Central Statistical Agency, DHS: Demographic Health Survey, Dr: Doctor, EA: Enumeration Area, EDHS: Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey, EMEDHS: Ethiopian Mini Demographic and Health Survey, EmOC: Emergency Obstetric Centre, EPHI: Ethiopia Public Health Institute, GIS: Geographic Information System, ICC: Intra-Class Correlation, ICF: Inner-City Fund, MDGs: Millennium Development Goals, MoH: Ministry of Health, MOR: Median Odds Ratio, MPH: Master of Public Health, Mr: Mister, NGOs: Non-Governmental Organizations, PCV: Proportional Change in Variance, PHC: Population and Housing Census, SBA: Skilled Birth Attendant, SDGs: Sustainable Development Goals, SNNP: Southern Nations and Nationality of People , SPSS: Statistical Package for Social Science , UN: United Nation, USAID: United States of America International Development, WHO: World Health Organization.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thanks Bahir Dar University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences for providing this opportunity and support to conduct this research. Thanks a lot Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency (CSA) for providing Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey data for this study.

Authors’ Contributions

YAM was responsible for a significant contribution to the conceptualization, study selection, data extraction, investigation, methodology, formal analysis and original and final draft preparation. Project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, and reviewing are all handled by MAA, HAG and EMA and the final draft of the work was read, edited and approved by all authors.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing Interests

None declared

Patient and Public Involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient Consent for Publication

Not required

Ethical Approval

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review committee of Bahir Dar University, CMHS. In addition a permission for data access was obtained from a measure Demographic and Health Survey through an online request at (http://www.dhsprogram.com). The data used for this study were publicly available with no personal identifier. Our study was based on secondary data from Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey and we have secured the permission letter from the Measure Demographic Health and Survey.

Data Availability

The data used in this study are the third-party data which is Demographic and Health Survey available at (http://www.dhsprogram.com). So, to access the data, someone needs to follow the steps and protocol outlined under the methods section or the data is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

- World health statistics 2019 (2019) Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals.

- WHO UUatW (2015) Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015. [Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/publications/trends-maternal-mortality-1990-2015.

- WHO U, UNFPA WBG, the UNPD (2019) Trends in Maternal Mortality: 2000 to 2017. [Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/featured-publication/trends-maternal-mortality-2000-2017

- UNICEF (2022) Maternal mortality. [Available from: https://gdc.unicef.org/resource/maternal-mortality

- Loewe M (2014) The United Nations Global Compact International Yearbook 2014. UN-library.

- Tessema GA, Laurence CO, Melaku YA, Misganaw A, Woldie SA, et al (2017) Hiruye A, et al. Trends and causes of maternal mortality in Ethiopia during 1990-2013: findings from the Global Burden of Diseases study 2013. BMC public health 17(1): 1-8. [crossref]

- USAID (2021) Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health: Ethiopia. [Available from: https://www.usaid.gov/ethiopia/global-health/maternal-and-child-health.

- ICF CEa (2016) Demographic and Health Surveys. [Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR241/SR241.pdf

- Nations U (2015) Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development .: . Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. [Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication.

- Graham WJ, Bell JS, Bullough CH (2001) Can skilled attendance at delivery reduce maternal mortality in developing countries? Safe motherhood strategies: a review of the evidence. 2001.

- Organization WH. Maternal health – GLOBAL [Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/maternal-health#tab=tab_1.

- Organization WH (2019) Maternal mortality – World Health Organization. [Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329886/WHO-RHR-19.20-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- UNICEF (2017) UNICEF Annual Report 2016. [Available from: https://www.unicef.org/reports/unicef-annual-report-2016.

- Fund UNP (2015) Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015. [Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/publications/trends-maternal-mortality-1990-2015

- WHO (2004) Making pregnancy safer: the critical role of the skilled attendant: a joint statement by WHO, ICM and FIGO.

- Organization WH (2004) Making pregnancy safer: the critical role of the skilled attendant: a joint statement by WHO, ICM and FIGO: World health organization.

- ICF CEa (2016) Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF (2016) Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. CSA and ICF, Addis Ababa, Rockville. – References – Scientific Research Publishing [Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers.aspx?referenceid=2860060.

- UNICEF (2021) Delivery care 2021 [Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/delivery-care/.

- Tiruneh SA, Lakew AM, Yigizaw ST, Sisay MM, Tessema ZT (2020) Trends and determinants of home delivery in Ethiopia: further multivariate decomposition analysis of 2005-2016 Ethiopian Demographic Health Surveys. BMJ Open 10(9): e034786. [crossref]

- Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tunçalp Ö, Moller AB, et al (2014) Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health2(6): e323-33. [crossref]

- Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggeshall MS, Shackelford KA, Steiner C, et al. (2014) Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 384(9947): 980-1004. [crossref]

- Antenatal care and skilled birth attendance in Bangladesh are influenced by female education and family affordability: BDHS 2014. Public Health. 2019.

- Asamoah BO, Agardh A, Pettersson KO, Östergren P-O (2014) Magnitude and trends of inequalities in antenatal care and delivery under skilled care among different socio-demographic groups in Ghana from 1988-2008. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 14(1): 295[crossref]

- Jacobs C, Moshabela M, Maswenyeho S, Lambo N, Michelo C (2017) Predictors of antenatal care, skilled birth attendance, and postnatal care utilization among the remote and poorest rural communities of Zambia: a multilevel analysis. Frontiers in Public Health 5: 11[crossref]

- Henry V. Doctor SEF, Giorgio Cometto, Godwin Y. Afenyadu (2013) Awareness of Critical Danger Signs of Pregnancy and Delivery, Preparations for Delivery, and Utilization of Skilled Birth Attendants in Nigeria. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved.

- Olakunde BO, Adeyinka DA, Mavegam BO, Olakunde OA, Yahaya HB, et al. (2019) Factors associated with skilled attendants at birth among married adolescent girls in Nigeria: evidence from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, 2016/2017. International Health 11(6): 545-50. [crossref]

- Ameyaw EK, Dickson KS (2020) Skilled birth attendance in Sierra Leone, Niger, and Mali: analysis of demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health 20(1): 1-10. [crossref]

- Mathewos Oridanigo E, Kassa B (2022) Utilization of Skilled Birth Attendance among Mothers Who Gave Birth in the Last 12 Months in Kembata Tembaro Zone. Advances in Medicine 2022.

- Teshale AB, Alem AZ, Yeshaw Y, Kebede SA, Liyew AM, et al (2020) Exploring spatial variations and factors associated with skilled birth attendant delivery in Ethiopia: geographically weighted regression and multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health 20(1): 1444.

- UNICEF (2019) The 2019 Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey. [Available from: https://www.unicef.org/ethiopia/reports/2019-ethiopia-mini-demographic-and-health-survey

- K (2018) SatScan user guide 2006.

- Bartko JJ (1966) The intraclass correlation coefficient as a measure of reliability. Psychological reports 19(1): 3-11. [crossref]

- Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A, editors (2012) Understanding variability in multilevel models for categorical responses. Proceedings of the AERA Annual Meeting, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

- Alemayehu M, Mekonnen W (2015) The prevalence of skilled birth attendant utilization and its correlates in North West Ethiopia. BioMed Research International. 2015. [crossref]

- Fekadu M, Regassa N (2014) Skilled delivery care service utilization in Ethiopia: analysis of rural-urban differentials based on national demographic and health survey (DHS) data. African Health Sciences 14(4): 974-84. [crossref]

- Yusuf MS, Kodhiambo M, Muendo F, Kariuki JG (2018) Determinants of access to skilled birth attendants by women in Galkacyo district, Somalia: KENYATTA UNIVERSITY.

- Amoakoh-Coleman M, Ansah EK, Agyepong IA, Grobbee DE, Kayode GA,et al (2015) Predictors of skilled attendance at delivery among antenatal clinic attendants in Ghana: a cross-sectional study of population data. BMJ Open 5(5): e007810. [crossref]

- Tessema ZT, Tesema GA (2020) Pooled prevalence and determinants of skilled birth attendant delivery in East Africa countries: a multilevel analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 46(1): 1-11.

- Gaffey MF, Das JK, Bhutta ZA, editors (2015) Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5: Past and future progress. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 20(5): 285-92. [crossref]

- Regassa LD, Tola A, Tusa BS, Weldesenbet AB. Trends, (2020) Spatial Pattern and Determinants of Skilled Birth Attendant Utilization in Ethiopia: Data from Ethiopian Demographic and Health Surveys (2005, 2011 and 2016)

- Biza N, Mohammed H (2016) Pastoralism and antenatal care service utilization in Dubti District, Afar, Ethiopia, 2015: A cross-sectional study. Pastoralism 6(1): 15.

- Gitonga E (2017) Skilled birth attendance among women in Tharaka-Nithi County, Kenya. Advances in Public Health. 2017.

- Pathak PK, Singh A, Subramanian S (2010) Economic inequalities in maternal health care: prenatal care and skilled birth attendance in India, 1992-2006. PloS one 5(10): e13593. [crossref]

- Bhowmik J, Biswas R, Woldegiorgis M (2019) Antenatal care and skilled birth attendance in Bangladesh are influenced by female education and family affordability: BDHS 2014. Public Health 170: 113-21. [crossref]

- Kibria GMA, Burrowes V, Choudhury A, Sharmeen A, Ghosh S,et al (2018) A comparison of practices, distributions and determinants of birth attendance in two divisions with highest and lowest skilled delivery attendance in Bangladesh. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 18(1): 1-10.

- Ameyaw EK, Tanle A, Kissah-Korsah K, Amo-Adjei J (2016) Women’s health decision-making autonomy and skilled birth attendance in Ghana. International Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2016. [crossref]

- Joseph G, da Silva ICM, Barros AJ, Victora CG (2018) Socioeconomic inequalities in access to skilled birth attendance among urban and rural women in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health 3(6): e000898.

- Mengesha ZB, Biks GA, Ayele TA, Tessema GA, Koye DN (2013) Determinants of skilled attendance for delivery in Northwest Ethiopia: a community based nested case control study. BMC Public Health. 13(1): 1-6.

- Nyongesa C, Xu X, Hall JJ, Macharia WM, Yego F,et al (2018) Factors influencing choice of skilled birth attendance at ANC: evidence from the Kenya demographic health survey. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 18(1): 88. [crossref]

- Carter MW, Speizer I (2005) Salvadoran fathers’ attendance at prenatal care, delivery, and postpartum care. Revista panamericana de salud publica 18(3): 149-56. [crossref]

- Manyeh AK, Akpakli DE, Kukula V, Ekey RA,et al (2017) Socio-demographic determinants of skilled birth attendant at delivery in rural southern Ghana. BMC Research Notes 10(1): 1-7. [crossref]

- Hazarika I (2011) Factors that determine the use of skilled care during delivery in India: implications for achievement of MDG-5 targets. Maternal and Child Health Journal 15(8): 1381-8. [crossref]

- Budu E, Chattu VK, Ahinkorah BO, Seidu A-A, Mohammed A, et al (2021) Early age at first childbirth and skilled birth attendance during delivery among young women in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 21(1): 834. [crossref]

- Kola L, Bennett IM, Bhat A, Ayinde OO, Oladeji BD,et al (2020) Stigma and utilization of treatment for adolescent perinatal depression in Ibadan Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 20: 1-8. [crossref]

- Mengesha ZB, Biks GA, Ayele TA, Tessema GA, Koye DN. (2013) Determinants of skilled attendance for delivery in Northwest Ethiopia: a community based nested case control study 13(130)

- Bintabara D (2021) Addressing the huge poor-rich gap of inequalities in accessing safe childbirth care: A first step to achieving universal maternal health coverage in Tanzania. Plos One 16(2): e0246995. [crossref]

- Talukder S, Farhana D, Vitta B, Greiner T (2017) In a rural area of Bangladesh, traditional birth attendant training improved early infant feeding practices: a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. Maternal & Child Nutrition 13(1) [crossref]

- Umeh CA, Feeley FG (2017) Inequitable Access to Health Care by the Poor in Community-Based Health Insurance Programs: A Review of Studies From Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Global Health, Science and Practice 5(2): 299-314. [crossref]

- Fisseha G, Berhane Y, Worku A, Terefe W (2017) Distance from health facility and mothers’ perception of quality related to skilled delivery service utilization in northern Ethiopia. Int J Womens Health 9: 749-56. [crossref]

- Ogolla JO (2015) Factors associated with home delivery in West Pokot County of Kenya. Advances in Public Health 2015(1): 1-6

- Stephenson R, Baschieri A, Clements S, Hennink M, Madise N (2006) Contextual influences on the use of health facilities for childbirth in Africa. American Journal of Public Health 6(1): 84-93. [crossref]