DOI: 10.31038/EDMJ.2024822

Abstract

Introduction: Neonatal hypoglycemia is a metabolic problem characterized by decreased in blood glucose. It is the leading cause of neonatal mortality and is associated with multiple factors associated with neonatal hypoglycemia. However, there are limited studies on the prevalence and factors associated with neonatal hypoglycemia in the study area.

Objective: This study aimed to assess the prevalence and associated factors of neonatal hypoglycemia among neonates admitted to neonatal intensive care units in Northwest Amhara Region Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia, in 2022.

Method: An institutional-based cross-sectional study was carried out among 497 neonates admitted to neonatal intensive care units in Northwest Amhara Region Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals from October 3, 2022 to November 3, 2022. A systematic random sampling technique was used to select study participants. Data were collected through maternal interviews using structured questionnaires and neonatal chart reviews using checklists. Finally, the data were entered into Epi-Data version 4.6.0.6 and analyzed using STATA version 14.0. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the variables. Both bi-variable and multi-variable logistic regression models were used for the analysis. AOR and 95% CI were used to measure association and strength, with statistical significance assessed at a p-value <0.05

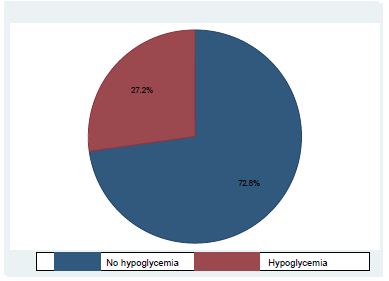

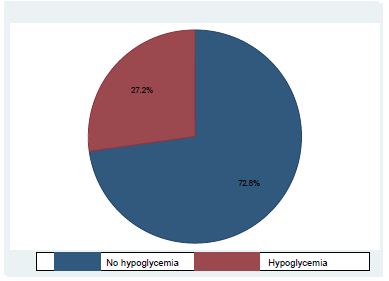

Results: The prevalence of neonatal hypoglycemia in the study area was 27.2% with 95%CI (23.4-31.4%). In this study variables such as maternal age 20-35 years [(AOR: 0.35, (95%CI: 0.167-0.73)], preterm birth [(AOR=2.60, 95%CI: 1.07-6.36)], low birth weight [(AOR: 3.07, 95%CI: 1.26-7.46)] and hypothermia [(AOR: 2.58, 95%CI: 1.27-5.23)], were factors associated with neonatal hypoglycemia.

Conclusions and recommendations: The prevalence of neonatal hypoglycemia in the neonatal intensive care unit of the northwest Amara region is relatively high. Preterm, low birth weight and hypothermia were significant factors for neonatal hypoglycemia. It is better for neonatal care providers in neonatal intensive care units to prioritize premature newborns or those with low birth weight and to follow the warm chain protocol.

Keywords

Hypoglycemia, NICU, Prevalence

Background

The term “hypoglycemia” refers to a low blood glucose level [1]. Neonatal hypoglycemia is defined as a blood glucose level of less than 40 mg/dL (2.2 mmol/L) [2]. It can be transient or persistent, and most cases of neonatal hypoglycemia are transient and respond simply to treatment, with a good prognosis [3]. The numerical explanation of neonatal hypoglycemia remains controversial [4]. Neonatal hypoglycemia is the most common metabolic problem observed in neonatal intensive care units [5].

In developing countries, the overall prevalence of neonatal hypoglycemia is 5%-15% of all babies [6]. In Sub-Saharan Africa, neonatal hypoglycemia affects (11%-30.5%) in all newborns [7-9]. Neonatal mortality is highest in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) with mortality rates (NMR) of 24, and 27 deaths per 1,000 live births respectively, and hypoglycemia is a contributing factor [10,11]. Studies have found that neonates with hypoglycemia had higher mortality than neonates with normoglycemic [12-14].

Ethiopia ranks among the top countries with the highest number of neonatal deaths and has made little progress in lowering the neonatal mortality rate (NMR), According to the 2019 Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey (EDHS), NMR in Ethiopia was 33 /1000 live births [15]. Neonatal hypoglycemia is the most significant contributor to neonatal mortality [16]

Severe, prolonged hypoglycemia in the neonatal period can have devastating outcomes, including apnea, irritability, lethargy, seizures, long-term neurodevelopmental disabilities, cerebral palsy, and death. Neonates with persistent hypoglycemia have significantly higher rates of morbidity and mortality and 25 to 50% have developmental disabilities [17,18].

Direct costs attributable to the acute management of neonatal hypoglycemia can be large, particularly if the infant is admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit [19]. Both healthcare-related costs and the impact on quality of life due to, the long-term outcomes of neonatal hypoglycemia accrue over the lifetime of neonates [20]. Neonates who experienced neonatal hypoglycemia had a combined discounted hospital and post-discharge cost greater than neonates without hypoglycemia [21]

Various studies have shown that certain variables are associated with neonatal hypoglycemia, including premature infants; small for gestational age (SGA); large for gestational age (LGA); post-maturity; twins; infants of diabetic mothers; infants born to mothers who receive high-glucose infusion before delivery, delayed initiation of feeding, perinatal asphyxia, sex of the baby, meconium aspiration syndrome, and respiratory distress syndrome(RDS) [7,9,22,23].

There are limited studies in Ethiopia on the prevalence and factors associated with neonatal hypoglycemia among newborns admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit in the Northwest Amhara Region Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals. Although the Ethiopian national guidelines recommend early initiation of breastfeeding and prevention of hypothermia at birth to prevent hypoglycemia due to maternal, neonatal, and institutional problems, delays in feeding initiation and hypothermia are major problems observed among neonates admitted to NICUs [24]. Therefore this study aimed to determine the prevalence of neonatal hypoglycemia and identify the factors associated with neonatal hypoglycemia among newborns admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit in the Northwest Amhara Region Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals.

Methods and Materials

Study Design, Period, and Setting

An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted from October 3, 2022, to November 3; 2022. This study was conducted in the Northwest Amhara region’s comprehensive specialized hospital, in Northwest Ethiopia. The Amhara region is the second-largest and most populous Region in Ethiopia with a total population of a 31 million [25]. In the Northwest Amhara region, there are five comprehensive specialized hospitals (CSH). These were the University of Gondar CSH, Felege Hiwot CSH, Tibebe Ghion CSH, Debre Tabor CSH, and Debre Markos CSH. The UoGCSH is located in the town of Gondar. Although neonatal hospitalization varies, this hospital has an average annual admission of 4560 and an average monthly admission of 380 neonates. Felege Hiwot and Tibebe Ghion CSH were found in Bahir Dar. These hospitals have an average annual neonatal admission of 1836 and 1920 neonates, and an average monthly admission of 153 and 160, respectively. Debre Tabor CSH, which is found in Debre Tabor town, has an average annual neonatal admission of 1560, and an average monthly admission of 130. Debre Marko’s CSH was found in the town of Debre Marko’s. This hospital has 1692 annual neonatal admissions; an average monthly admission of 141. These hospitals have NICUs with a mix of health professionals (neonatal and comprehensive nurses, general practitioners, pediatricians, and other staff). The major services in the NICU include general neonatal care services, blood and exchange transfusions, phototherapy, and ventilation support such as continuous positive air pressure.

Population Selection and Participation

The source population consisted of all neonates and their mothers who were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit of the Northwest Amhara Region Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals. All neonates with their mothers who were admitted to the neonatal intensive care units during the study period comprised the study population. All neonates with their mothers who were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit during the time of data collection were included in the study. Neonates whose mothers were critically ill, abandoned neonates and neonates with incomplete charts during the data collection period were excluded from the study.

Sample Size Determination and Sampling Procedures

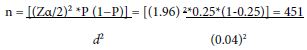

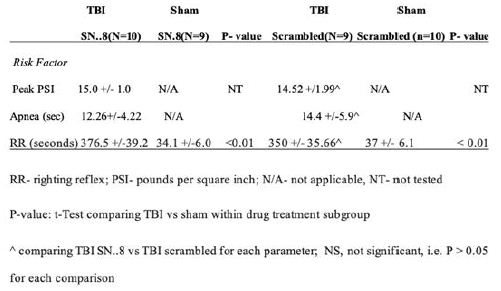

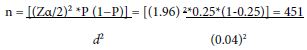

For the first objective, the sample size was calculated by using a single population proportion formula taking the prevalence of neonatal hypoglycemia at 25% in St. Paul Hospital [9]

P=proportion hypoglycemia=25%

d = margin of error 4%

Z α/2= the corresponding Z score of 95% CI=1.96

n = Sample size.

By adding a 10% non-response rate, a total of 497 participants were included in the study.

For the second objective, the sample size was calculated using the double proportion formula by considering significant factor variables (Table 1).

Table 1: Sample size calculation by factors for the second objective. Data were collected through a review of the neonate’s medical chart it is not experiments on humans and/or the use of human tissue samples.

|

Neonatal Hypoglycemia

|

|

Variables

|

P1 |

P2 |

Power |

OR |

Sample size

|

| Prematurity |

66%

|

22.89% |

80% |

6.537(26) |

55 |

|

Low birth weight

|

24.3% |

9.75% |

80% |

2.979(26) |

258

|

| Finally, the largest sample size which is obtained by the first objective (497) was taken. |

Sampling Technique and Procedure

In the Northwest Amhara region, there were five comprehensive specialized hospitals: UoGCSH 380/month, FHCSH 153/month, TGCSH 160/month, DTCSH 130/month, and DMCSH has 141/month. In total, 964 neonates and their mothers were admitted to the hospital from October 3, 2022, to November 3, 2022. Based on the final calculated sample size proportional allocation was performed for each hospital. Systematic random sampling was used in this study. The k interval was determined (964/497; K = 2). After determining the Kth interval, the first neonates with mothers were selected randomly, and then based on the bed number of the neonates every other two neonates with mothers were selected using a systematic sampling technique.

Study Variables and Their Measurements

The outcome variable was the prevalence of neonatal hypoglycemia among neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit. The independent variables were as follows: 1. socio-demographic factors (maternal age, residency, marital status, educational status and maternal occupation); 2. Obstetric factors (ANC follow-up, parity, mode of delivery, duration of labor, place of delivery, number of current pregnancies) 3. Maternal factors (DM, pregnancy-induced hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, maternal HIV/AIDS, maternal drugs) 4. Neonatal factors (sex, gestational age, age at admission, birth weight, weight for gestational age, time of initiation of feeding, perinatal asphyxia (PNA), temperature, respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), sepsis, meconium aspiration syndrome)

Neonatal Hypoglycemia

A baseline or first blood glucose measurement value of less than 40 mg/dl in neonates [27].

Hypothermia

A baseline axillary body temperature below 36.5°C [28].

Perinatal Asphyxia

Apgar score of less than 7 in the 5th minute.

Macrosomia

Birth weight of 4000 grams and above.

Neonatal Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Diagnosed based on the presence of one or more of the following signs: an abnormal respiratory rate, expiratory grunting, nasal flaring, chest wall recessions, and thoracoabdominal asynchrony with or without cyanosis [29], and Physician diagnosis.

Pregnancy-induced Hypertension

Blood pressure greater than 140/90 mm Hg occurring after the 20th week of pregnancy or during the first 24 hours postpartum without evidence of proteinuria.

Preeclampsia

New-onset hypertension with proteinuria with or without edema.

Eclampsia

It is the development of convulsions coma or both in the clinical setting of preeclampsia.

Small for Gestational Age

It is related to birth weight and gestational age if the birth weight is less than the 10th percentile [28]

Large for Gestational Age

It is related to birth weight and gestational age if the birth weight is greater than the 90th percentile [28]

Incomplete Chart

Charts with one of the following factors are missed (gestational age, birth weight, neonatal age, parity, place of delivery, body temperature, maternal age and type of pregnancy, and random blood glucose level.

Data Collection Tool and Procedure

The data were collected using interviewer-administered and chart review through structured, pretested questionnaires that were adapted from a questionnaire developed from previous studies [9,20,23,28,31,42]. The questionnaire contains four sections: The first section contains five questions regarding the socio-demographic characteristics of the mothers. The second section contains six questions regarding the obstetric characteristics of the mothers; the third section contains six questions regarding maternal-related characteristics, and the fourth section contains eleven questions related to neonatal-related characteristics. The data were collected by five BSc nurses who worked in a neonatal intensive care unit and supervised by four MSc nurse professionals. Primary data was collected through structured questionnaires by using interviews, and secondary data were collected through a review of the neonate’s medical chart by using checklists to take the baseline neonatal characteristics such as blood glucose, body temperature, and birth weight.

Data Quality Assurance

To ensure the quality of the data, a pretest was given among 5% (25) neonates with their mothers at Dessie CSH. The training was given to all data collectors and supervisors on the purpose of the study, how to get informed consent, and the technique of selecting the study participants from the neonatal intensive care unit. The data was further assured through careful planning and translation of the questionnaire; the English version was translated into the local language, Amharic. To maintain the validity of the tool, its content was reviewed by senior pediatric and child health specialist nurses and instructors. Then the questions were checked for clarity, completeness, consistency, sensitivity, and ambiguity. The completeness of the collected data was checked onsite daily during data collection and received prompt feedback from the supervisor and the principal investigator. All completed data collection forms were examined for completeness and consistency during data management, storage, cleaning, and analysis.

Data Processing and Analysis

Data were checked, coded, and entered into Epi-Data version 4.6.0.6 and exported to STATA version 14 for analysis. Descriptive statistics were carried out using the mean, frequency, percentage, proportion, tables, and figures to present the findings. The outcome variable was dichotomized and coded as 0 and 1, representing those who are not hypoglycemia and hypoglycemia, respectively. Pearson rank chi-square assumption fulfillment was checked for categorical variables. An adjusted odd ratio (AOR) with a 95% CI was used to assess the relationship between factors associated with the occurrence of the outcome variable. A logistic regression model was used, and bi-variable and multi-variable logistic regression was done to determine the association between each independent variable and the outcome variable. Variables having p-value <0.25 in variables logistic regression analysis were taken into multivariable logistic regression analysis. In multivariable analyses, variables whose p-value was ≤, 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Multicollinearity was checked by using variance inflation factors (VIF = 1.04–4.17, mean VIF=1.59) and model goodness of fit test was checked by Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit tests (p = 0.55)

Results

Socio-demographic Characteristics of the Mothers

In this study, a total of 497 study participants were enrolled, with a response rate of 96.18% The mean (±SD) age of mothers was 28.33 (±4.8) years, and the majority of 398 (83.25%), were between the ages of 20 and 35, with 273 (57.11%) living in urban. Of the mother’s educational status 124 (25.94%) completed secondary school and 142 (29.71%) were college and above; the majority of participants 455 (95.19%) were married (Table 2).

Table 2: Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants in Northwest Amhara region comprehensive specialized hospitals, 2022(n=478).

|

Variables

|

Categories |

frequency(n) |

Percent (%)

|

| Maternal age |

<20 years |

17

|

3.56

|

| 20-35 years |

398

|

83.26

|

| >35Years |

63

|

13.18

|

| Marital status |

Married |

455

|

95.19

|

|

Single |

19

|

3.97

|

| Divorced |

4

|

0.84

|

| Residency |

Urban |

273

|

57.11

|

| Rural |

205

|

42.89

|

| Educational status |

unable to read and write |

128

|

26.78

|

| primary school |

84

|

17.57

|

| Secondary school |

124

|

25.94

|

| College and above |

142

|

29.71

|

| Occupation |

Government Employee |

99

|

20.71

|

| Private employee |

38

|

7.95

|

| Merchant |

63

|

13.18

|

| Daily labor |

5

|

1.05

|

| House Wife |

273

|

57.11

|

Maternal Clinical Related Factors

Among a total of 478 participants, 47 (9.83%) were diabetics Miletus, of which 42 (89.36) gestational diabetics Miletus; 69 (14.44%) were pregnancy-induced hypertension, of which 46 (66.67) eclampsia; 46 (9.62%) were given medications during pregnancy, and 16 (3.35%) were given medications during labor (Table 3).

Table 3: Maternal Clinical related factors of study participants in Northwest Amhara region comprehensive specialized hospitals, 2022(n=478).

|

Variables

|

Categories |

Frequency (n) |

Percent (%)

|

| Maternal diabetic Mellitus |

Yes |

47

|

9.83 |

|

No

|

431 |

90.17

|

| Type of diabetic mellitus |

Pre gestational |

5

|

10.64 |

|

Gestational

|

42 |

89.36

|

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension |

Yes |

69

|

14.44 |

|

No

|

409 |

85.56

|

| Type Pregnancy-induced hypertension |

Preeclampsia |

23

|

33.33 |

|

Eclampsia

|

46 |

66.67

|

| Medication use during Pregnancy (Except iron-folic acid) |

Yes |

46

|

9.62 |

|

No

|

432 |

90.38

|

| Type of medication use during pregnancy |

Amoxicillin |

2

|

4.35 |

|

Magnesium sulfate

|

38 |

82.6

|

| Hydrazine |

2

|

4.35 |

|

Ceftriaxone

|

4 |

8.7

|

| Medication is given during labor and delivery |

Yes |

16

|

3.35 |

|

No

|

462 |

96.65

|

| Type of Medication given during labor and delivery |

Oxytocin |

6

|

37.5 |

|

Ampicillin

|

4 |

25

|

| Dexamethasone |

6

|

37.25 |

|

HIV/AIDS

|

Yes

|

9 |

1.88

|

| No |

469

|

98.12

|

Obstetric Related Factors

Out of 478 maternal interviews and reviewed charts neonates admitted in NICU regarding Obstetric factors-More than half, 248(51.88%) of mothers were multipara. 425 (88.91%) had ANC follow-up, and 454 (94.98%) had a duration of labor less than 24 hours. Around two-thirds, 306 (64.02%) of mothers gave birth via spontaneous vaginal delivery (Table 4).

Table 4: Obstetric factors of study participants in Northwest Amhara region comprehensive specialized hospitals, 2022(n=478).

|

Variables

|

Category |

Frequency(n) |

Percent (%)

|

| Parity |

Primipara |

230

|

48.12 |

|

multi para

|

248 |

51.88

|

| ANC follows up on the current pregnancy |

Yes |

425

|

88.91 |

|

No

|

53 |

11.09

|

| Number of ANC follow-up |

1 time |

12

|

2.51 |

|

2times

|

37 |

7.74

|

| 3 times |

125

|

26.15 |

|

4 and above

|

251 |

52.51

|

| Duration of labor |

<24 hours |

454

|

94.98

|

| >24 hours |

24

|

5.02

|

| Place of delivery |

Hospital |

294

|

61.51

|

| Health center |

64

|

34.31 |

|

Home

|

20 |

4.18

|

| Modes of delivery |

Spontaneous vaginal delivery |

306

|

64.02 |

|

Assisted vaginal delivery

|

52 |

10.88

|

| Cesarean section |

120

|

25.10 |

|

Number of current pregnancies?

|

Single

|

410 |

85.77

|

| multiple |

68

|

14.23

|

Neonatal Related Factors

Among admitted neonates more than half of 263 (55.02%) were male. Around 207 (43.31%) were preterm and 213 (44.56%) of them had low birth weight. Around two-thirds (65.6%) of the neonates had hypothermia. in respect of to Weight for Gestational age 439 (91.84%) was appropriate for gestational age. 223 (46.65%) of neonates were started feeding within one hour. Around one-third, 149 (31.17%) of the neonates had respiratory distress syndrome, and 60 (12.55%) of the neonates were meconium aspiration syndrome (Table 5).

Table 5: Neonatal-related factors of study participants in Northwest Amhara region comprehensive specialized hospitals, 2022(n=478).

|

Variables

|

Category

|

Frequency(n) |

Percent (%)

|

| Male |

263

|

55.02 |

|

Female

|

215 |

44.98

|

| Age at admission |

<24 hours |

351

|

73.43 |

|

≥24 hours

|

127 |

26.57

|

| Gestational age |

Preterm |

207

|

43.31 |

|

Term

|

261 |

54.60

|

| Post-term |

10

|

2.09 |

|

Birth weight

|

Low birth weight

|

213 |

44.56

|

| Normal birth weight |

254

|

53.14 |

|

Macrosomia

|

11 |

2.30

|

| Weight for Gestational age |

Small for gestational age |

22

|

4.60 |

|

Appropriate for gestational age

|

439 |

91.84

|

| Large for gestational age |

17

|

3.56 |

|

Axillary body temperature at admission

|

Hypothermia

|

287 |

60.04

|

| Normothermic |

154

|

32.22 |

|

hyperthermia

|

37 |

7.74

|

| Initiation of feeding |

Within one hour |

223

|

46.65 |

|

After one hour

|

255 |

53.35

|

| Respiratory distress syndrome |

Yes

No |

149

329

|

31.17

68.83

|

| No |

329

|

68.83

|

| Meconium aspiration syndrome |

Yes |

60

|

12.55 |

|

No

|

418 |

87.45

|

| Sepsis |

Yes |

290

|

60.67 |

|

No

|

188 |

39.33

|

| PNA |

Yes |

49

|

10.25 |

|

No

|

429 |

89.75

|

| Neonatal hypoglycemia |

Yes |

130

|

27.20 |

|

No

|

348 |

72.80

|

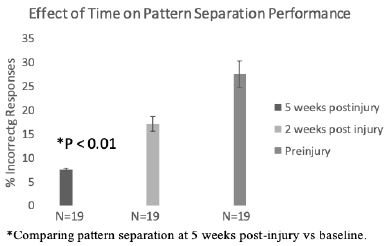

Prevalence of Neonatal Hypoglycemia

The study revealed that the prevalence of baseline neonatal hypoglycemia was found to be 27.2% with 95%CI (23.4-31.4%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Prevalence of neonatal hypoglycemia among neonates admitted to neonatal intensive care units in Northwest Amhara Region Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia, 2022.

Factors Associated with Neonatal Hypoglycemia

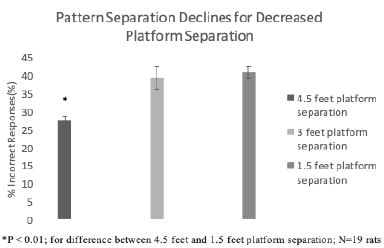

Bivariable analysis was carried out on all of which variables having p-value <0.25: maternal age, maternal diabetes miletus, pregnancy-induced hypertension, medication use during pregnancy and labor, parity, place of delivery, duration of labor and mode of delivery, age at admission, feeding initiation time, gestational age, birth weight, axillary body temperature, RDS, PNA, and sepsis. Then multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to adjust possible confounders. In multivariable logistic regression analysis factors that were significantly associated which showed p-value < 0.05 neonatal hypoglycemia were After controlling confounders in the final model, maternal age between 20 and 35 years, preterm, low birth weight, and hypothermia.

Maternal age group 20- 35 years old were 65% less likely to be hypoglycemic (COR; 95%CI 0.35, 0.17-0.73) as compared to the maternal age above 35 years old of the mothers.

Preterm neonates were 2.6 times more likely to be hypoglycemic as compared to term neonates (AOR = 2.60, 95% CI: 1.07, 6.36).

Low-birth-weight neonates were 3.07 times more likely to be hypoglycemic than neonates delivered with normal birth weight (AOR = 3.07, 95%, CI: 1.26–7.46).

The neonates who had hypothermia were 2.58 times more likely to develop neonatal hypoglycemia as compared to those who had normal body temperature (AOR = 2.58, 95% CI: 1.27–5.23) (Table 6).

Table 6: Bi-variable and multivariable logistic regression of neonatal hypoglycemia among neonates admitted to neonatal intensive care units in Northwest Amhara Region Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia, 2022.

|

Variable

|

Categories |

Neonatal Hypoglycemia |

COR with 95% CI |

AOR with 95% CI |

| Yes |

No

|

| Maternal age |

<20 years |

8 (47.06%)

|

9(52.94%) (52.2.94%) |

1.44(0.49-4.25) |

1.13(0.29-4.37) |

|

20-35 years

|

98 (24.62%) |

300 (75.38%) |

0.53(0.30- 0.93) |

0.35(0.167-0.73)**

|

| >35Years |

24 (38.10%)

|

39(61.90%) |

1 |

1 |

|

Maternal diabeticmellits

|

Yes

|

18(38.30%) |

29(61.70%) |

1.77(0.95- 3.31) |

1.87(0.86-4.06)

|

| No |

112(25.99%)

|

319(74.01%) |

1 |

1

|

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension |

Yes |

28(40.58%)

|

41(59.42%) |

2.06(1.21-3.49) |

1.07(0.47- 2.45)

|

| No |

102(24.94%)

|

307(75.06%) |

1 |

1

|

| Medication use during pregnancy pregnancy |

Yes |

22(47.83%)

|

24(52.17%) |

2.75(1.49-5.10) |

2.11(0.81-5.52)

|

| No |

108(25.00%)

|

32(475.00%) |

1 |

1

|

| Medication use during labor |

Yes |

7(43.75%)

|

9(56.25%) |

2.14(0.78-5.88) |

2.41(0.70-8.30)

|

| No |

123(26.62%)

|

339(73.38%) |

1 |

1

|

| Parity |

Primipara |

70(30.43%)

|

160(69.57%) |

1.37(0.92-2.05) |

1.37(0.81-2.34)

|

|

Multipara |

60(24.19%)

|

188(75.81%) |

1 |

1

|

| Duration of labor |

<24 hours |

120(26.43%)

|

334(73.57%) |

1 |

1

|

| >24 hours |

10(41.67%)

|

14(58.33%) |

1.99(0.86-4.60) |

2.08(0.67-6.45)

|

| Place of delivery |

Hospital |

90(30.61%)

|

204(69.39%) |

1 |

1

|

| Health center |

36(21.95%)

|

128(78.05%) |

0.64(0.41-0.99) |

0.68 (0.39-1.19)

|

| Home |

4(20.00%)

|

16(80.00%) |

0.57(1.18-1.74) |

0.93(0.25-3.50)

|

| Mod of delivery |

SVD |

70(22.88%)

|

236(77.12%) |

1 |

1

|

| Instrumental |

14(26.92%%

|

38(73.08%) |

1.24(0.64-2.4) |

1.62(0.73-3.63)

|

|

C/s |

46(38.33%)

|

74(61.67%) |

2.09(1.33-3.3) |

1.19(0.65-2.17)

|

| Age at admission |

<24 hours |

107(30.48%)

|

244(69.52%) |

1.98(1.19 -3.28) |

0.67(0.33-1.37)

|

| >24 hours |

23(18.11%)

|

104(81.89%) |

1 |

1

|

| Gestational age |

Term |

32(12.26%)

|

229(87.74%) |

1 |

1

|

| Preterm |

96(46.38%)

|

111(53.62%) |

6.18(3.91-9.80) |

2.60(1.07-6.36)*

|

| Post-term |

2(20.00%)

|

8(80.00%) |

1.79(0.36-8.79) |

1.15(0.19-7.03)

|

| Birth weight |

Normal birth weight |

31(12.20%)

|

223(87.80%) |

1 |

1

|

| Low birth weight |

98(46.01%)

|

115(53.99%) |

6.13(3.86-9.73) |

3.07(1.26-7.46)*

|

|

Macrosomic |

1(9.09%)

|

10(90.91%) |

0.72(0.09-5.81) |

0.83 (0.09-747)

|

| Body temperature |

Hypothermia |

111(38.68%)

|

176(61.32%) |

5.84(3.26-10.47) |

2.58(1.27- 5.23)**

|

| Hyperthermia |

4(10.81%)

|

33(89.19%) |

1.12(0.845-0 .35) |

2.14(0.59-7.63)

|

| Normothermic |

15(9.74%)

|

139(90.26%) |

1 |

1

|

| Initiation of feeding |

Within 1 hour |

33(14.80%)

|

190(85.20%) |

1 |

1

|

|

After 1 hour |

97(38.04%)

|

158(61.96%) |

3.53(2.26-5.53) |

1.75(0.97-3.15)

|

| Respiratory distress syndrome |

Yes |

62(41.61%)

|

87(58.39%) |

2.74(1.79-4.17) |

0.55(0.28-1.05)

|

| No |

68(20.67%)

|

261(79.33%) |

1 |

1

|

| Sepsis |

Yes |

64(22.07%)

|

226(77.93%) |

0.52(0.34-0.78) |

0.91 (0.55 -1.53)

|

| No |

66(35.11%)

|

122(64.89%) |

1 |

1

|

| PNA |

Yes |

17(34.69%)

|

32(65.31%) |

1.49(0.79-2.78) |

1.69(0.72-3.99)

|

| No |

113(26.34%)

|

316(73.66%) |

1 |

1

|

Discussion

This study revealed that the prevalence of neonatal hypoglycemia was 27.2% with 95%CI (23.4-31.4%). The findings are consistent with those previously conducted in Ethiopia St. Paul Hospital (25%) [9] and Nigeria (30.5%) [30]. The possible reasons in Ethiopia St. Paul Hospital may have used a similar study design and similarity in the neonatal intensive care unit setting and the possible reasons in Nigeria may be due to similar sources of the population were used.

On the other hand, the findings of this study are lower than the study conducted in Iraq (39.1%) [31] and New Zealand (51%) [23]. This may be because these two studies were used among neonates identified as high-risk groups. In Iraq, the study was conducted among low birth weight and preterm neonates and excluded healthy term newborns, whereas in New Zealand source of the population only infants of diabetic mothers.

On the contrary, the result of this study is higher than the study conducted in Eastern Ethiopia (21.2%) [32], Uganda (2.2%) [33] and (7.5%) [34], Côte d’Ivoire (15.9) [35], Nigeria (11%) [22], India (15.38%) [36], Israel (23.2) [37], Iraq (16.25%) [38], and China (16.9%) [39] The possible explanation for Uganda may be due to the difference in the study area and the number of study participants. It was conducted in the community which is different from institutional-based because less likely to gate healthy individuals compared to the community-based study area and the large number of study participants involved in the study. In Nigeria, the possible reasons may be that the study conducted included a smaller sample size, and neonates less than 24 hours of age were included in the study [22]. The study conducted in Iraq and India excludes infants born to diabetic mothers, neonates born to hypertensive mothers, and newborns with severe congenital malformations [36,38]. Another possible justification is that the study conducted in China used a lower cut-off point (30.6 mg/dL) to diagnose neonatal hypoglycemia compared to the current study [39].

Neonates delivered from mothers who had a maternal age of 20- 35 years old were 65% less likely to develop neonatal hypoglycemia as compared to the maternal age above 35 years old of the mothers. This finding is supported by Saint Paul‘s Hospital in Ethiopia [9] and India [40]. The possible justification is that mothers who are 20–35 years old are more likely to have higher levels of maternal human capital, which includes maturity, experience, self-esteem, and mental health, than older mothers (> 35 years old) [41]. The ideal childbearing age is between 20 and 35 years old. This is the time when having the highest number of good quality eggs available and pregnancy-related risks are lowest compared to maternal ages older than 35 years [42]. Advanced maternal age at birth (35 years and older) is associated with gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia, preterm birth, low birth weight, low Apgar scores, and neonatal hypoglycemia [43]

The study revealed that preterm neonates were 2.6 times more likely to be hypoglycemic as compared to term neonates. This finding is supported by a study conducted in Eastern Ethiopia [32], Nigeria [7], New Zealand [23], Iran [38], Indonesia [26], and Macedonia [44]. The possible reason may be that preterm newborns have higher metabolic demands. In preterm infants, the enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis are expressed at low levels; thus, their ability to produce endogenous glucose is poor, contributing to their risk of severe or prolonged low glucose concentrations [45]. Preterm neonates are uniquely predisposed to developing hypoglycemia and its associated complications due to their limited glycogen and fat stores, their inability to generate new glucose using gluconeogenesis pathways, and their decreased ability to breastfeed effectively [46]

In this study, low birth weight neonates were 3.07 times more likely to be hypoglycemic as compared to normal birth weight neonates. This is in keeping with other studies in the study: Khartoum [47], Nigeria [7], New Zealand [23], Indonesia [26], and Japan [48], Since neonates with low birth weight are at risk for hypoglycemia because they are born with decreased glycogen stores, decreased adipose tissue and experience increased metabolic demands because of their relatively large brain size [49].

According to the current study, hypothermic neonates were 3.58 times more likely to be hypoglycemic as compared to neonates with normal body temperature. This finding is supported by the studies conducted in Eastern Ethiopia [32], Uganda [34], Nigeria [22], Israel [50], Iran [38], China [39] and India [40]. The possible justification is that newborn hypothermia develops, the baby gets cold, and it uses up more glycogen to keep warm. Then the baby must utilize his glucose stores to keep warm, and then the blood sugar drops and they become hypothermic and hypoglycemic, and the glucose requirement increases in neonates who have hypothermia, which will increase the utilization of glucose [51].

Limitations of the Study

This study does not include other risk factors like Polycythemia, rhesus hemolytic disease, and neonatal jaundice because the study design is a cross-sectional study design.

This study does not see the fluctuation of blood glucose after the management of neonates having low blood glucose.

Conclusions

The prevalence of neonatal hypoglycemia in the study area was relatively high. Furthermore, it was found that maternal age between twenty and thirty-five, preterm birth, low birth weight, and hypothermia were significantly associated with neonatal hypoglycemia.

Recommendations

For Hospitals and Health Care Providers

Every neonatal intensive care unit should have its own thermostat and humidity control so that neonatal intensive care unit personnel can adjust the thermostat as needed for any neonates. Neonatal intensive care units’ temperature and humidity should be documented four times per day. The postnatal and neonatal intensive care units should be suitably arranged for the delivery unit so that mothers can’t be in difficulty of skin-to-skin contact during intra-facility transportation. The practice of warm chain should also be supervised regularly.

Neonatal care providers have to adhere to the routine practice of warm chain by giving the most prioritized attention to newborns with health problems, preterm and low birth weight newborns Mothers should also be oriented about thermal care during their antenatal care while they are in labor, delivery, and postnatal unit. The mothers also apply kangaroo mother care especially for preterm and low birth weight newborns.

Health education about neonatal hypoglycemia and its risk factors and preventive measures should be given to all families starting from ANC follow-up.

It is better to regularly screen out pregnant mothers for maternal obstetric factors like pregnancy-induced hypertension and chronic illness so that they will be alarmed as this can put them at risk of delivery being preterm and low birth weight which may lead to poor neonatal adaptation and many associated co-morbidity that leads to neonatal hypoglycemia. Healthcare providers who work in the labor and delivery ward and neonatal intensive care unit routinely check the neonates’ blood sugar levels.

Amhara Health Bureau

Integrate the need for training for health professionals on general prevention of hypoglycemia and develop standard protocols for all facilities to aware all the health professionals attending delivery and working in NICUs. To strengthen the service of the neonatal intensive care unit, medical equipment and medical team including a neonatologist, pediatrician, medical doctor, and neonatal nurse have to fulfill.

Researchers

Further studies have to be carried out to address the other factors associated with neonatal hypoglycemia and also to determine the outcomes of this hypoglycemia neonate using a follow up study.

Declarations

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

AGA developed the research idea, designed the study, and was involved in proposal writing, training and supervision of the data collectors, analysis and interpretation of the results, and preparation of the manuscript. EGM and AWA participated in the critical revision of the proposal, study design, analysis and interpretation of the results, and writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review committee of the School of Nursing on behalf of the institutional review board of the University of Gondar. An official letter was written to the Northwest Amhara region’s Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals for permission and support from the Ethical Review Committee of the School of Nursing with ref. no. SN/032/2015 on 03/10/2022 (G.C.) and with ref.no. SN/032/2015.A written permission letter was obtained from Amhara Public Health Institute for each hospital (ref. no. አሕጤኢ/ዋ/ዳ/03/1611). Finally, permission was obtained from the NICU head of each hospital to access the mother’s and neonates’ medical charts. As this is a prospective study, consent must come from the mothers. The confidentiality of the information was strictly maintained by omitting any personal identifier (name and medical record number) during the data collection.

Acknowledgments

First, the authors would like to express their deepest gratitude to the University of Gondar, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, and School of Nursing for providing me with this opportunity and financial support. Next, we would also like to acknowledge the Amhara Public Health Institute for permitting me to conduct the study at each hospital, and we would also like to thank the Northwest Amhara Region Comprehensive Specialized Hospital NICU Coordinators and healthcare providers for giving me general information related to the study area and study population. Finally, we would also like to extend our special thanks to the data collectors, supervisors, and study participants for their great contributions to the success of this study.

Funding Statement

Financial support was received from University of Gondar. The funding institution had no role in the preparation of the manuscript or in the decision to publish.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Berard LD, Blumer I, Houlden R, Miller D, Woo V (2013) Monitoring glycemic control. Canadian journal of diabetes. 37: S35-S9. [crossref]

- NICU guideline 2021. 2017;1: 277.

- Training NICUN, Manual P (2021) Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) TrainingParticipants’ Manual Federal Ministry of Health. 2021.

- Kallem VR, Pandita A, Gupta G (2017) Hypoglycemia: when to treat? Clinical Medicine Insights: Pediatrics. 11: 1179556517748913. [crossref]

- Hansen AR, Stark AR, Eichenwald EC, Martin CR (2022) CLoherty and Stark’s Manual of neonatal care: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;

- Makker K, Alissa R, Dudek C, Travers L, Smotherman C, Hudak ML (2018) Glucose gel in infants at risk for transitional neonatal hypoglycemia. American Journal of Perinatology. 35(11): 1050-6. [crossref]

- Efe A, Sunday O, Surajudeen B, Yusuf T (2019) Neonatal hypoglycemia: prevalence and clinical outcome in a tertiary health facility in North-Central Nigeria. Int J Health Sci Res. 9: 246-51.

- Mukunya D, Odongkara B, Piloya T, Nankabirwa V, Achora V, Batte C, et al (2020) Prevalence and factors associated with neonatal hypoglycemia in Northern Uganda. [crossref]

- Nurussen I, Fantahun B (2021) Prevalence And Risk Factors of Neonatal Hypoglycaemia at St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Pediatrics and Child Health. 16(1).

- Blencowe H, Krasevec J, De Onis M, Black RE, An X, Stevens GA, et al (2019) National, regional, and worldwide estimates of low birth weight in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 7(7): e849-e60.[crossref]

- Wardlaw T, You D, Hug L, Amouzou A, Newby H (2014) UNICEF Report: enormous progress in child survival but greater focus on newborns urgently needed. Reproductive health. 11(1): 1-4. [crossref]

- Dedeke I, Okeniyi J, Owa J, Oyedeji G (2011) Point-of-admission neonatal hypoglycemia in a Nigerian tertiary hospital: incidence, risk factors and outcome. Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics. 38(2): 90-4.

- El-Mekkawy MS, Ellahony DM (2019) Prevalence and prognostic value of plasma glucose abnormalities among full-term and late-preterm neonates with sepsis. Egyptian Pediatric Association Gazette. 67(1): 1-7.

- Masaba BB, Mmusi-Phetoe RM (2020) Neonatal survival in Sub-Sahara: a review of Kenya and South Africa. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. 13: 709.[crossref]

- Demographic E (2019) Health survey: Addis Ababa. Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistics Agency and ORC macro.

- EN. T (2021) Clinical Reference Manual for Advanced Neonatal Care in Ethiopia Ministry of Health ©UNICEF.. Frontiers in Endocrinology 12: : 59-62.

- De Angelis LC, Brigati G, Polleri G, Malova M, Parodi A, Minghetti D, et al (2021) Neonatal hypoglycemia and brain vulnerability. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 12: 634305.

- Thornton PS, Stanley CA, De Leon DD, Harris D, Haymond MW, Hussain K, et al(2015) Recommendations from the Pediatric Endocrine Society for evaluation and management of persistent hypoglycemia in neonates, infants, and children. The Journal of Pediatrics. 167(2): 238-45.[crossref]

- Glasgow MJ, Harding JE, Edlin R, Alsweiler J, Chase JG, Harris D, et al (2018) Cost analysis of treating neonatal hypoglycemia with dextrose gel. The Journal of Pediatrics. 198: 151-5. e1.[crossref]

- Harding JE, Harris DL, Hegarty JE, Alsweiler JM, McKinlay CJ (2017) An emerging evidence base for the management of neonatal hypoglycemia. Early human development. 104: 51-6.[crossref]

- Glasgow MJ, Edlin R, Harding JE (2021) Cost burden and net monetary benefit loss of neonatal hypoglycemia. BMC Health Services Research. 21(1): 1-13.[crossref]

- Ochoga MO, Aondoaseer M, Abah RO, Ogbu O, Ejeliogu EU, Tolough GI (2018) Prevalence of Hypoglycaemia in Newborn at Benue State University Teaching Hospital, Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria. Open Journal of Pediatrics. 8(2): 189-98.

- Mitchell NA, Grimbly C, Rosolowsky ET, O’Reilly M, Yaskina M, Cheung P-Y, et al (2020) Incidence and risk factors for hypoglycemia during fetal-to-neonatal transition in premature infants. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 8: 34. [crossref]

- Tesfay EN (2021) Clinical Reference Manual for Advanced Neonatal Care in Ethiopia Ministry of Health 2021 ©UNICEF. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 12: 59-62.

- Ethiopia FDRo (2019) Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) Assessment (Regional Government of Amhara) Final Report

- Yunarto Y, Sarosa GI (2019) Risk factors of neonatal hypoglycemia. Paediatrica Indonesiana. 59(5): 252-6.

- Ng. 2021. 2017;2017;1: 277.

- Lunze K, Hamer D (2012) Thermal protection of the newborn in resource-limited environments. Journal of Perinatology. 32(5): 317-24. [crossref]

- Sweet DG, Carnielli V, Greisen G, Hallman M, Ozek E, Te Pas A, et al (2019) European consensus guidelines on the management of respiratory distress syndrome–2019 update. 115(4): 432-50. [crossref]

- West B, Aitafo J (2020) Prevalence and Clinical Outcome of Inborn Neonates with Hypoglycaemia at the Point of Admission as seen in Rivers State University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. Journal of Pediatrics, Perinatology and Child Health. 4(4): 137-48. [crossref]

- Rajab AS, Chalabi DA, Al-Rabaty AA (2018) Prevalence and severity of hypoglycemia in a sample of neonates in Erbil city. Zanco Journal of Medical Sciences (Zanco JMed Sci) 22(1): 13440.

- Sertsu A, Nigussie K, Eyeberu A, Tibebu A, Negash A, Getachew T, et al (2022) Determinants of neonatal hypoglycemia among neonates admitted at Hiwot Fana Comprehensive Specialized University Hospital, Eastern Ethiopia: A retrospective cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Medicine. 10: 20503121221141801. [crossref]

- Mukunya D, Odongkara B, Piloya T, Nankabirwa V, Achora V, Batte C, et al (2020) Prevalence and factors associated with neonatal hypoglycemia in Northern Uganda: a community-based cross-sectional study. Tropical Medicine and Health. 48(1): 1-8. [crossref]

- Nabuuma T (2022) Prevalence and factors associated with abnormal glycemic status among term neonates admitted to special care unit Kawempe National Referral Hospital: Makerere University.

- Ouattara GJ, Cissé L, Koffi G, Yao J-JA, Enoh J, Sei C, et al (2017) Clinical and Epidemiological Features and Management of Neonatal Hypoglycemia at the University Teaching Hospital of Treichville (Abidjan-Côte d’Ivoire) Open Journal of Pediatrics. 7(4): 320-30.

- Magadla Y (2016) Infants of diabetic mothers: maternal and infant characteristics and incidence of hypoglycemia: Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand.

- Zigron R, Rotem R, Erlichman I, Rottenstreich M, Rosenbloom JI, Porat S, et al (2022) Factors associated with the development of neonatal hypoglycemia after antenatal corticosteroid administration: It’s all about timing. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 158(2): 385-9. [crossref]

- Sabzehei MK, Otogara M, Ahmadi S, Daneshvar F, Shabani M, Samavati S, et al (2020) Prevalence of Hypoglycemia and Hypocalcemia Among High-Risk Infants in the Neonatal Ward of Fatemieh Hospital of Hamadan in 2016-2017. Hormozgan Medical Journal. 24(1): e94453e.

- Zhou W, Yu J, Wu Y, Zhang H (2015) Hypoglycemia incidence and risk factors assessment in hospitalized neonates. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 28(4): 422-5. [crossref]

- Sasidharan C, Gokul E, Sabitha S (2010) Incidence and risk factors for neonatal hypoglycemia in Kerala, India. Ceylon Medical Journal. 49(4)

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry. 62(6): 593-602.

- Fall CH, Sachdev HS, Osmond C, Restrepo-Mendez MC, Victora C, Martorell R, et al (2015) Association between maternal age at childbirth and child and adult outcomes in the offspring: a prospective study in five low-income and middle-income countries (COHORTS collaboration) The Lancet Global Health. 3(7): e366-e77.

- Wambach KA, Cole C (2000) Breastfeeding and adolescents. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 29(3): 282-94. [crossref]

- Stomnaroska O, Petkovska E, Jancevska S, Danilovski D (2017) Neonatal hypoglycemia: risk factors and outcomes. Prilozi (Makedonska akademija na naukite i umetnostite Oddelenie za medicinski nauki)

- Carmen S (1986) Neonatal hypoglycemia in response to maternal glucose infusion before delivery. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 15(4): 319-23.

- Sharma A, Davis A, Shekhawat PS (2017) Hypoglycemia in the preterm neonate: etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, management and long-term outcomes. Translational pediatrics. 6(4): 335. [crossref]

- Hussein SM, Salih Y, Rayis DA, Bilal JA, Adam I (2014) Low neonatal blood glucose levels in cesarean-delivered term newborns at Khartoum Hospital, Sudan. Diagnostic Pathology. 9(1): 1-4.

- Shimokawa S, Sakata A, Suga Y, Isoda K, Itai S, Nagase K, et al. Incidence and risk factors of neonatal hypoglycemia after ritodrine therapy in premature labor: a retrospective cohort study. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Care and Sciences. 2019;5(1): 1-7.

- Abramowski A, Ward R, Hamdan AH. Neonatal hypoglycemia (2021) StatPearls [Internet]: StatPearls Publishing;.

- Bromiker R, Perry A, Kasirer Y, Einav S, Klinger G, Levy-Khademi F (2019) Early neonatal hypoglycemia: incidence of and risk factors. A cohort study using universal point of care screening. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 32(5): 786-92.

- Adamkin DH, editor Neonatal hypoglycemia (2017) Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine; Elsevier.