Abstract

We present the emerging science of Mind Genomics, to understand people’s responses to health-related issues, specifically pain. Mind Genomics emerge out of short, affordable, scalable, east-to-run experiments. The topic, here pain, is deconstructed into four questions, each with four separate answers (elements.) The answers are combined into vignettes, presented to respondents, who rate the entire vignette. Emerging from the study are the ratings and the response times to the vignettes, both of which are deconstructed into the contributions of the different underlying elements which the vignettes comprise. The answers cannot be gamed, and the data quickly reveal what is important to the individual, as well as revealing the existence of new-to-the-world mind-sets which differ in the pattern of elements that they find important. Mind Genomics provides the opportunity to understand the person’s needs and wants for specific health as well as other experiential situations where human judgment is relevant.

Introduction

Pain is an inevitable companion in our life’s journey. Pain is defined through its association with actual or potential tissue damage, denoting it as a necessary characteristic of the experience, but also recognizing that events other than tissue damage can serve as determinants, consistent with a bio psychosocial model of pain [1,2]. This definition of pain denotes multiple causal factors underlying pain, beyond the issue pathology.

There is no dearth of studies on pain, whether these studies are report of pain from one’s everyday life [3], a topic dealt with in medicine [4], and a topic of scientific investigation [5]. When we talk about pain, can we probe into the mind of the person beyond simply the report, beyond a simplistic scale? Can we move beyond simple indicators, approaching a more detailed description of one’s pain but yet not forcing the respondent to become a scientist?

Pain, a highly subjective phenomenon, often refers to a sensory experience resulting from actual damage to the body or from non-bodily damage [6]. Pain may be influenced by psychological mechanisms such as: attention, emotion, beliefs and expectations [7].

In general, there are two different classifications of physical pain, visceral and somatic. Visceral pain originates in the internal organs whereas somatic pain stems from skin, muscle, soft tissue, and bone. There are many types of pain which fall under these categories. A person’s pain can also be classified as acute or chronic. Pain can be described as nerve pain, psychogenic pain, muscle pain, abdominal pain, back pain, pelvic pain, etc.

Subjective pain is influenced by its intensity and by interventions to treat the pain. Expectations and attitudes towards pain, may stem from psychological processes that are fundamental to learning across various sensory experiences and affect. Understanding expectations and attitudes towards pain may help us form communication messaging to help individuals deal more effectively with their chronic pain.

The subjective nature of pain makes it difficult to test the actual nature of perceived pain across populations, within a country, and in different countries. There are accepted methods of testing the actual perception of pain, specifically pain thresholds and pain tolerance, as well as psychophysical scaling of pain. One example is measuring the time one can submerge a limb in an ice bath, to test the ability of subjects to tolerate pain under varying conditions, most notable with the testing of analgesics of anesthetics. These methods give a measure of the all-or-none response to pain, and even the qualitative nature of the pain, but do not give a sense of the mind of the person who is undergoing the pain.

Increase in pain accompanies one’s beliefs that a certain treatment will cause pain or increase one’s symptoms overtime [7]. Negative beliefs regarding pain and its effects may occur in some types of chronic pains. To test whether expectations affect pain, studies tested the extent to which expectations influenced physiological responses among individuals. Placebo treatments truly reduced pain intensity [8–12]. These studies also indicated that short-term expectations varied and strongly affected perceptions of pain and pain-evoked responses [13].

Other studies linked differences in expectations regarding pain to the magnitude of responses to pain treatments [14]. Research on the relationship between expectations and pain experiences, showed that expectations about treatments and painful stimuli profoundly influenced behavioral markers of pain perception [7].

Pain treatments also bring positive changes in negative emotions [15]. Expectations affect pain through attention, executive functioning, value learning, anxiety and negative emotions [16]. Attitudes towards pain such as anxiety raised subjective pain. Pain is, thus a complex experience, involving sensory, motivational, and cognitive components. Affect any one of these components may change one’s attitudes towards pain [7].

Whereas studies indicate that beliefs influenced pain experience, it is unclear to what extent psychological processes such as attention, anxiety and emotions affect choice of treatments and what communication messages may mediate the effects of these psychological processes. This study tests communication messaging that affect emotion, attitudes towards pain and choice of treatment for pain.

In his book, Pain: The Gift Nobody Wants, author Paul Brand, MD describes his observations across cultures. Growing up as the child of missionaries in India and then moving to the US, Brand noted the difference in pain and suffering that existed in the East versus the West. He noted that, “as a society gained the ability to limit suffering, it lost the ability to cope with what suffering remains”. He stated that he believed that Easterners have learned to control pain at the level of the mind and spirit whereas, Westerners tend to view pain and suffering as an injustice or failure and an infringement on their right to happiness [17].

In the newly developing science of Mind Genomics we attempt to demonstrate a richer understanding of one’s inner life by presenting the respondent (or ill/healthy pain sufferer, here) with vignettes describing the inner experience, instructing the respondent to rate the fit of the vignettes, one at a time, and then estimating the degree to which each of the elements of the vignette ‘fits’ the respondent.

Method

Mind Genomics as an emerging science has been previously presented [18]. Mind Genomics works by presenting respondents with vignettes, combinations of statements which together tell a story. The respondent is instructed to judge the vignette, rating the vignette as a totality. The rating scale for this study is simply ‘How well does this describe you?’

The statements, elements in the language of Mind Genomics, present simple ideas. The approach requires the construction of four questions which ‘tell a story.’ For each question, the researcher is required to provide four answers, all expressed in simple language. Table 1 presents the four questions, and the four answers to each question. Ideally, the questions and answers should deal with the topic, here pain, but need not mention pain directly. Rather, the questions and answers should be relevant to the topic.

Table 1. The four questions and the four answers to each question.

|

Question A: how would you describe the nature of pain you are feeling?

|

|

Pain bothers me all over my body

|

|

The pain is localized but intolerable

|

|

The pain radiates and makes it difficult to function

|

|

The pain is minor but frequent and annoying

|

|

Question B: Describe a situation that would make you feel more comfortable

|

|

The doctor explains to me how to deal with the pain

|

|

I try to deal with the pain to work through it

|

|

I’m happy when I can use a device that delivers therapeutic solution

|

|

I just like taking a pill that deals with the pain.

|

|

Question C: Describe how would you like to to avoid future pain

|

|

I would like to have a diet that is tailored to reduce my pain

|

|

I would like exercises and stretches that reduce pain

|

|

I would like regular therapy sessions to reduce my pain

|

|

I would like a prescription that gives me the medication I need to feel better

|

|

Question D: Describe what you would like the doctor to do

|

|

The doctor should give me advice

|

|

The doctor should give me a shot that delivers long term relief

|

|

The doctor should set me up with a system for me to follow

|

|

The doctor should give me a regular schedule of visits to treat my pain

|

The answers in Table 1 are combined by experimental design into a set of 24 vignettes, with each vignette comprising 2–4 elements. Table 2 shows an example of the first six vignettes. The elements appear an equal number of times. Each of the 16 elements is, by design, statistically independent of every other element.

Table 2. The first seven vignettes for the first respondent, created by the experimental design. The table shows the combinations, then the combinations transformed into binary, and then the ratings.

|

Vig1

|

Vig2

|

Vig3

|

Vig4

|

Vig5

|

Vig6

|

Vig7

|

|

A

|

4

|

0

|

4

|

3

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

|

B

|

3

|

2

|

1

|

2

|

1

|

1

|

3

|

|

C

|

4

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

4

|

3

|

|

D

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

0

|

3

|

1

|

4

|

|

Binary

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

|

A2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

A3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

A4

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

B1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

|

B2

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

B3

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

|

B4

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

C1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

C2

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

C3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

|

C4

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

|

D1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

|

D2

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

D3

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

|

D4

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

|

Rating

|

7

|

8

|

4

|

7

|

9

|

7

|

9

|

|

Binary

|

100

|

100

|

0

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

|

RT (response time) in seconds

|

10

|

6

|

9

|

6

|

10

|

8

|

7

|

Each respondent evaluates a unique set of 24 vignettes. The underlying mathematical structure of the experimental design is maintained, but the specific combinations are changed, in a permutation scheme which preserves the mathematical properties of the design [19]. The permutation covers many more combinations of elements compared to the standard approach of creating one experimental design and presenting that design to many respondents. The Mind Genomics achieves stability by testing many combinations, each a single time, but the expanded coverage ensures that a great of the ‘space of combinations’ is covered. It is difficult to be very ‘wrong’ with a Mind Genomics study because the scope. In contrast, traditional research works with a very small experimental design, e.g., equivalent to the combinations tested by one person, but the combinations are tested by many respondents in order to obtain a stable estimate of the value for each combination.

Mind Genomics and traditional statistics are on opposite sides in terms of what generates valid data. Is valid data obtained by sampling a few of the many possible combinations, albeit with stability for each point (traditional), or by sampling a great many of the combinations, albeit with less stability at any point. A good analogy to Mind Genomics is, metaphorically, the MRI, which discovers the configuration of tissue by taking different ‘snapshots’ and integrating them into one picture. With the permuted experimental one need not ‘be sure’ that the limited number of combinations is the correct set to represent the total set of possible alternatives. With as few as 25 respondents, the number of respondents participating, generating a total of 720 different combinations has covered the space quite well.

Running the Mind Genomics experiment

The experiment is run on the web, typically with respondents from a specific population who have agreed to participate (e.g., those being treated for a condition), or more typically with respondents recruited from the general population, when the objective is a quick ‘scan’ of what is important. The base sizes of these studies range from 25 for an exploration to 500 for a massive deconstruction of the population into different mind-sets. The more typical base size of 25–50 respondents reveals quite a bit about the nature of people’s minds with regard to a particular issue. This study shows the type of learning emerging from this small base size of respondents from the general population, and can be followed with many different studies to follow up on various interesting aspects.

The elements, answers to the questions, are created by experimental design [20]. The 16 elements are combined into 24 combinations or vignettes, similar in structure to the vignettes shown schematically in Table 2. The vignette can be presented on smartphones, tablets, or PC’s.

Although the respondent might feel that the vignettes are created in a random fashion, the reality is just the opposite. The vignettes are created within the framework of the design, which prescribe the exact combinations. The elements are placed one atop the other, centered, without any connectives, making the respondent’s task easier as the respondent ‘grazes for information’.

The experimental design ensures that the elements are statistically independent; appear several times against different backgrounds provided by the other elements in the vignette. Each respondent evaluates a unique set of 24 vignettes, permuted as noted above, so that the design structure is maintained but the specific combinations are new. The permutation system allows a great deal of the design space, or combinations, to be tested, and allows the information to emerge even when the researcher has absolutely no idea what will be important and what won’t. In other words, Mind Genomics is a discovery system, and not a confirmation system. One can learn quickly from a base of zero knowledge, simply by doing 1–4 easy studies of different facets of a topic.

The respondents who participated were US residents, members of a 10+ million world-wide panel of Luc.id Inc., who had previously agreed to participate in these studies for a reward administered by the panel provider. All respondents participated anonymously. The only information about the respondent was age, gender, and the answer to the third question about what type of pain they had. There were five answers to the third question, three dealing with chronic pain of various sorts, and two saying either ‘no pain,’ or ‘not applicable.’ All respondents were classified by gender, age, and by either pain/yes versus pain/no.

Preparing the data for analysis

The respondent assigns a rating to assess ‘How much does this describe how you feel’. The low anchor, 1, is ‘not at all.’ The high anchor, 9, is ‘very much.’ The Mind Genomics program bifurcates the scale, dividing it into the lower part, ratings of 1–6, transformed to 0, plus a very small random number (<10–5), and a high part, ratings of 7–9, transformed to 100, plus a very small random number. The bifurcation comes from the decades of experience which suggest that managers and scientists alike do not ‘understand’ the meaning or use of the Likert or category scale, but they easily understand the meaning of a no/yes, binary scale. The choice of where to bifurcate is left to the researcher. Thirty-five years of experiments suggest that a 2/3 vs 1/3 division seems to work well. The small random number added to the binary transformed data ensures that when it is time to run the OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression on the data at the level of the individual respondent, there will not be a ‘crash’ of the regression program when the respondent confined the ratings to either the low range (1–6) or to the high range (7–9.) Either of those two cases produces all 0’s or all 1’s, crashing the regression. The small random number ensures that there is variability in the dependent variable, the binary transformed data.

How the different elements drive the binary transformed rating

Table 3 shows the parameters and relevant statistics for the additive model created from the ratings of the total panel, after transformation to a binary scale. The model itself is a simple linear equation of the form: Binary Rating = k0 + k1(A1) + k2(A2) … K16(D4). The experimental design allows us to create the model either at the level of the individual respondent or at the grand level, combining all of the data from the ‘relevant’ respondents, with relevant being

Table 3. Parameters of the model for ‘Fits Me’ after binary transformation. The data come from the Total Panel (720 observations, 24 tested vignettes from each of 30 respondents.) The table is sorted in descending order of coefficient for ‘describes me.’ At the right is the associated coefficient for response time.

|

|

|

Coeff Desc.

|

T-stat

|

P-Value

|

Coeff RT

|

|

Additive constant

|

46

|

4.68

|

0.00

|

|

|

C2

|

I would like exercises and stretches that reduce pain

|

6

|

0.95

|

0.34

|

0.9

|

|

D3

|

The doctor should set me up with a system for me to follow

|

2

|

0.39

|

0.69

|

2.1

|

|

B2

|

I try to deal with the pain to work through it

|

2

|

0.39

|

0.70

|

1.9

|

|

A1

|

Pain bothers me all over my body

|

1

|

0.23

|

0.82

|

1.3

|

|

A3

|

The pain radiates and makes it difficult to function

|

0

|

0.05

|

0.96

|

1.6

|

|

C3

|

I would like regular therapy sessions to reduce my pain

|

-2

|

-0.28

|

0.78

|

1.7

|

|

D2

|

The doctor should give me a shot that delivers long term relief

|

-3

|

-0.53

|

0.59

|

1.8

|

|

D4

|

The doctor should give me a regular schedule of visits to treat my pain

|

-3

|

-0.58

|

0.56

|

1.7

|

|

B3

|

I’m happy when I can use a device that delivers therapeutic solution

|

-4

|

-0.65

|

0.52

|

2.1

|

|

D1

|

The doctor should give me advice

|

-4

|

-0.69

|

0.49

|

1.5

|

|

B1

|

The doctor explains to me how to deal with the pain

|

-4

|

-0.73

|

0.47

|

1.8

|

|

A4

|

The pain is minor but frequent and annoying

|

-5

|

-0.90

|

0.37

|

2.1

|

|

A2

|

The pain is localized but intolerable

|

-6

|

-0.95

|

0.34

|

1.2

|

|

C4

|

I would like a prescription that gives me the medication I need to feel better

|

-7

|

-1.19

|

0.24

|

1.4

|

|

C1

|

I would like to have a diet that is tailored to reduce my pain

|

-7

|

-1.22

|

0.22

|

1.4

|

|

B4

|

I just like taking a pill that deals with the pain.

|

-8

|

-1.35

|

0.18

|

1.6

|

The analysis suggests the following:

- Additive constant, the expected binary value in the absence of elements: Without any elements, the likely response that the vignette will ‘describe me’ is about 46%. By design, all vignettes comprised 2–4 elements, so the additive constant is an estimated parameter. Thus, the value of 46 for additive constant says that half the time respondents will answer that whatever appears will describe them. It is the elements which must do the work to move beyond this almost 50% agreement rate. It is worthwhile commenting here that this baseline of 46% is modest. When the topic is credit cards and the rating is ‘interested in acquiring this credit card,’ the additive constant plummets to about 10–15. When the topic is pizza and the rating is ‘interested in eating this pizza,’ the additive constant skyrockets to 60–70.

- There are no very strong elements for the total panel: That is, no element drives the description of ‘me.’ This weakness can either be the result of choosing the wrong elements, or the result of dealing with two or perhaps even three or more different populations, who describe their impressions by different terms, and who may live in quite different worlds of pain.

- The highest scoring element is C2, I would like exercises and stretches that reduce pain. This element generates a coefficient of only 6, and has a t-statistic of 0.95, with a probability of 0.34 that it came from a distribution with a true mean of 0. That is, it’s quite likely that were we to do this study again, we would come up with a coefficient much lower than 6, probably 0 or thereabouts.

- The remaining elements do not ‘fit’ the respondent: It may well be that the elements are simply incorrect and others will fit the respondent better, or more likely that we are dealing with a segmented population of individuals, some of whom feel that an element ‘fits them,’ whereas others feel that the same element ‘does not fit them.’ In such a situation the responses cancel each other, and we are left with a coefficient around 0, denoting ‘no fit.’

Key subgroups

We know three additional things about the respondent based upon the self-profiling questions completed during the study. The first is gender, the second is age, and the third is whether or not they suffer pain on a regular basis. In this computerized application, the respondent is required to select one of two genders (male/female), and required to put in the year of birth, which provides age. The third question is left to the discretion of the researcher. In this study is the selection of pain, with five options. Two options are defined as ‘no pain’ (actual selection of ‘no pain’ as an answer, selection of not applicable). The remaining three options as pain (i.e. pain in the limbs, back, etc.). We will look at gender, age, and self-reported pain as the three self-defined subgroups. We will also explore two new subgroups, mind-sets inherent in the population but revealed by understanding patterns of responses, behavioral patterns, rather than self-classification.

The focus of interest in Mind Genomics studies is on the additive constant as the ‘baseline,’ and then on the ‘story’ told by the winning elements. These elements are operationally defined as having a value of +6.51 or higher, which becomes 7 when rounded to the nearest whole number.

Gender

- Males show a higher additive constant than do females (57 vs 38). In the absence of elements, men are more likely to say that a vignette ‘describes ME.’ Women are less likely to say that, and require more specification.

- We get a good sense of what is important by looking at the elements which are most positive (most like me), and most negative (least like me)

- For men, the single phrase which most describes them is

C2: I would like exercises and stretches that reduce pain

- For men, the single phrase which least describes them is

C1: I would like to have a diet that is tailored to reduce my pain

- For women, the two phrases phrase which most describe them are

B2: I try to deal with the pain to work through it,

A1: Pain bothers me all over my body. The degree of fit is less, however, for these elements than the corresponding best fits for males.

- For women, the phrase which least describes them is

B4: I just like taking a pill that deals with the pain.

Age: Under 50 versus 50+

Respondents provided the year of their birth. One respondent did not provide the year and was eliminated from this particular analysis by age.

- Surprisingly, the additive constant is much higher for the younger respondents versus the for the older respondents (48 vs 31.)

- For the younger respondents, there are no strong elements which fit them. The two elements which most describe them are those which suggest control over the pain:

C2: I would like exercises and stretches that reduce pain

D3: The doctor should set me up with a system for me to follow

- For the younger respondents, the two elements which least describe them are those which suggest passivity, and no control over the pain.

B1: The doctor explains to me how to deal with the pain

B4: I just like taking a pill that deals with the pain.

- For the older respondents, the two elements which most describe them are actual experience to reduce the pain, as well as a description of the experience.

A3: The pain radiates and makes it difficult to function

C2: I would like exercises and stretches that reduce pain

- For the older respondents, the three elements which least describe them is passivity

D1: The doctor should give me advice

C4: I would like a prescription that gives me the medication I need to feel better

C1: I would like to have a diet that is tailored to reduce my pain

No pain versus pain

As part of the self-profiling classification, the respondents selected the type of pain, if any, afflicting them. The respondents who check any of the three types of pain assigned to the group saying YES. The remaining respondents were assigned to the group saying NO.

- The additive constant is virtually the same, 46 vs 48, meaning that in the absence of elements in the vignette; a little fewer than 50% of the responses will be ‘describes me.’

- For those with pain, the phrase which most describes them is

C2: I would like exercises and stretches that reduce pain.

- For those with pain, the element which least describes

C1: I would like to have a diet that is tailored to reduce my pain

- For those with no pain, virtually no element most describes them

- For those with no pain, many elements least describe. The strong element which least describes is

C4: I would like a prescription that gives me the medication I need to feel better

Mind-Sets: Dividing respondents by the patterns of their coefficients for a specific topic

We have just seen that there are some differences in terms of ‘describes me’ across genders, and across those who define themselves as having pain versus no pain. These are ways that people describe themselves. People may differ in ways that the researcher cannot describe in simple terms, or even in way that they themselves don’t understand.

A major tenet of Mind Genomics is that within any topic area, such as the description of pain presented here, there are fundamental differences across people, differences that are obvious once demonstrated, but differences limited to a single topic area. This is the case of the data here. Even within the small sample of 30 respondents we can extract two, possibly three different mind-sets. The method for extracting mind-sets has been previously described [21]. Quite simply, the technique is a matter of clustering the respondents into two or three groups based upon the pattern of their 16 coefficients. The statistical method of clustering is well accepted [22] All that remains is the clustering, extracting the small groups with the property that these mutually exclusive groups represent different ways of thinking about the topic.

Table 4 shows the results for the two mind-set segments emerging from the clustering of the 30 respondents. A base size of 25–30 suffices to reveal the nature of these different mind-sets, especially because the segments are so obviously different and interpretable.

Table 4. Coefficients for the binary-transformed scale ‘Describes me’ across gender, age, pain, and mind-set, respectively. Coefficients of +7 or more are presented in bold, and shaded.

|

|

|

Male

|

Female

|

Age<50

|

Age 50+

|

Pain Yes

|

Pain No

|

Mind Set 1: Wants a cure

|

Mind Set 2: Simplicity through the doctor

|

|

Additive constant

|

57

|

38

|

58

|

31

|

46

|

48

|

37

|

54

|

|

A1

|

Pain bothers me all over my body

|

1

|

4

|

-1

|

3

|

6

|

-9

|

10

|

-9

|

|

A2

|

The pain is localized but intolerable

|

-4

|

-4

|

-9

|

0

|

-3

|

-11

|

-2

|

-9

|

|

A3

|

The pain radiates and makes it difficult to function

|

1

|

1

|

-7

|

9

|

2

|

-4

|

10

|

-11

|

|

A4

|

The pain is minor but frequent and annoying

|

-11

|

2

|

-5

|

-2

|

-2

|

-12

|

-3

|

-8

|

|

B1

|

The doctor explains to me how to deal with the pain

|

-8

|

-1

|

-11

|

2

|

-7

|

1

|

3

|

-12

|

|

B2

|

I try to deal with the pain to work through it

|

-2

|

4

|

-1

|

4

|

4

|

-2

|

8

|

-3

|

|

B3

|

I’m happy when I can use a device that delivers therapeutic solution

|

-6

|

-3

|

-7

|

-1

|

-4

|

-2

|

1

|

-9

|

|

B4

|

I just like taking a pill that deals with the pain.

|

-9

|

-8

|

-12

|

-5

|

-7

|

-11

|

-16

|

1

|

|

C1

|

I would like to have a diet that is tailored to reduce my pain

|

-15

|

0

|

-5

|

-10

|

-10

|

-3

|

2

|

-17

|

|

C2

|

I would like exercises and stretches that reduce pain

|

13

|

-3

|

5

|

7

|

10

|

-5

|

9

|

3

|

|

C3

|

I would like regular therapy sessions to reduce my pain

|

-1

|

-3

|

-3

|

1

|

-2

|

-2

|

3

|

-7

|

|

C4

|

I would like a prescription that gives me the medication I need to feel better

|

-11

|

-4

|

-4

|

-9

|

-5

|

-14

|

-9

|

-5

|

|

D1

|

The doctor should give me advice

|

-7

|

-5

|

-1

|

-9

|

-4

|

-3

|

-2

|

-4

|

|

D2

|

The doctor should give me a shot that delivers long term relief

|

-9

|

0

|

-1

|

-5

|

-3

|

-3

|

-6

|

3

|

|

D3

|

The doctor should set me up with a system for me to follow

|

-1

|

2

|

5

|

-1

|

4

|

-2

|

-4

|

10

|

|

D4

|

The doctor should give me a regular schedule of visits to treat my pain

|

-10

|

1

|

0

|

-5

|

-2

|

-6

|

-8

|

4

|

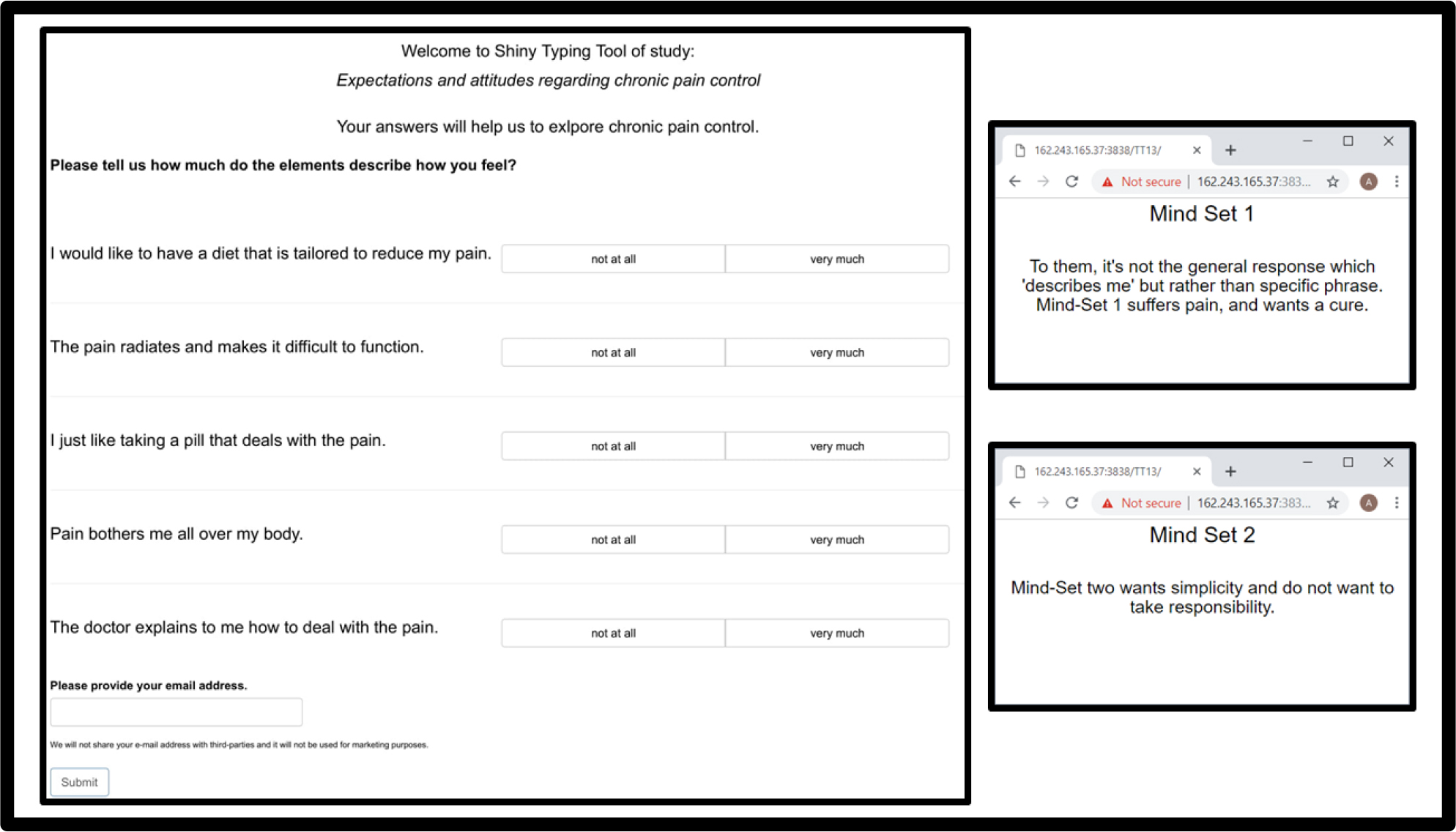

- Mind-Set 1 (wants a cure) begins with a low additive constant, 37. To them, it’s not the general response which ‘describes me’ but rather the specific phrase. Mind-Set 1 suffers pain, and wants a cure. Here are the elements which Mind-Set 1 feels best describes them:

A1: Pain bothers me all over my body

A3: The pain radiates and makes it difficult to function

C2: I would like exercises and stretches that reduce the pain

- Mind-Set 1 do not want simple medical treatment which will alleviate their pain. Here is the element which is they feel least describes them:

B4: I just like taking a pill that deals with the pain.

- Mind Set 2 (simplicity through the doctor) shows a higher additive constant, 54. Mind-Set 2 is less discriminating among elements. Mind-Set 2 wants simplicity. Here is the one element that they feel best describes them:

D3: The doctor should set me up with a system for me to follow

- Mind Set 2 does not want to take responsibility. Here are the elements that they feel least describe them:

C1: I would like to have a diet that is tailored to reduce my pain

B1: The doctor explains to me how to deal with the pain

A3: The pain radiates and makes it difficult to function

Response times as a measure of cognitive processing of information

At the same time that the respondents were reading the vignettes, the response time was being measured. Response time is operationally defined as the time between the appearance of the vignette and the assignment of the rating. The experiment was executed on the internet.

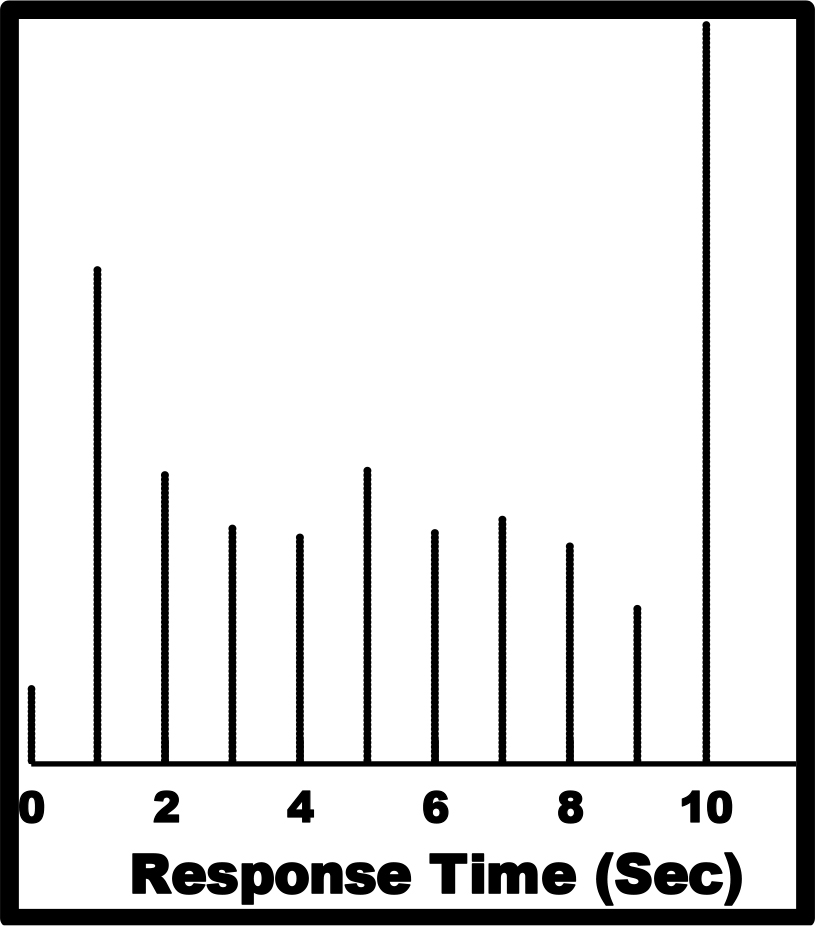

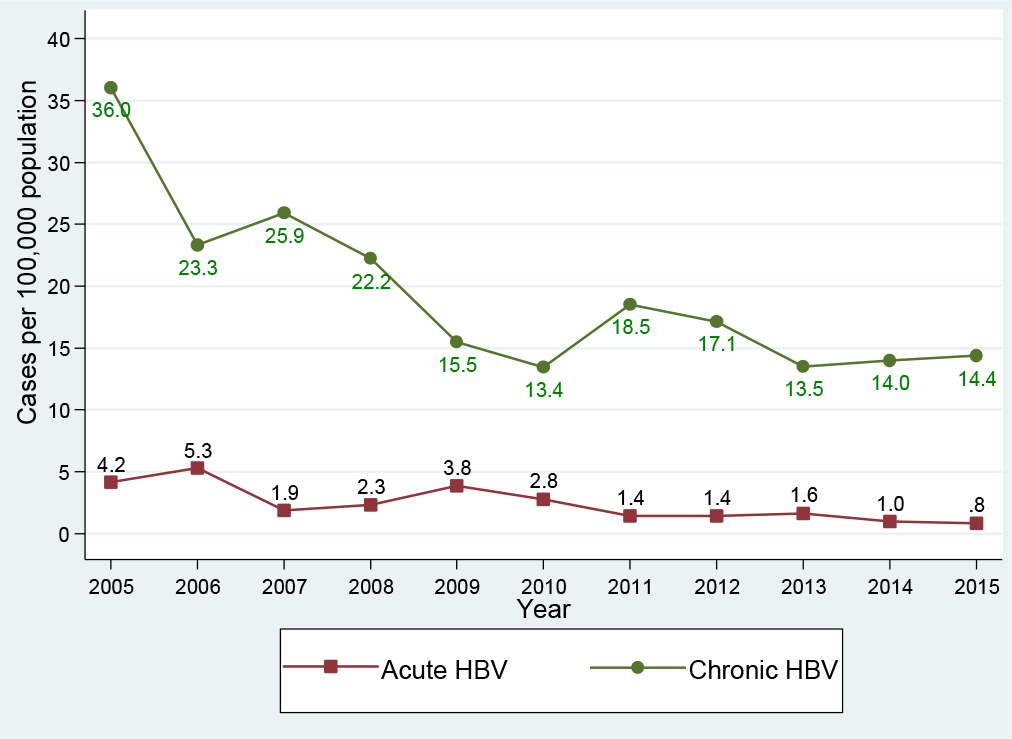

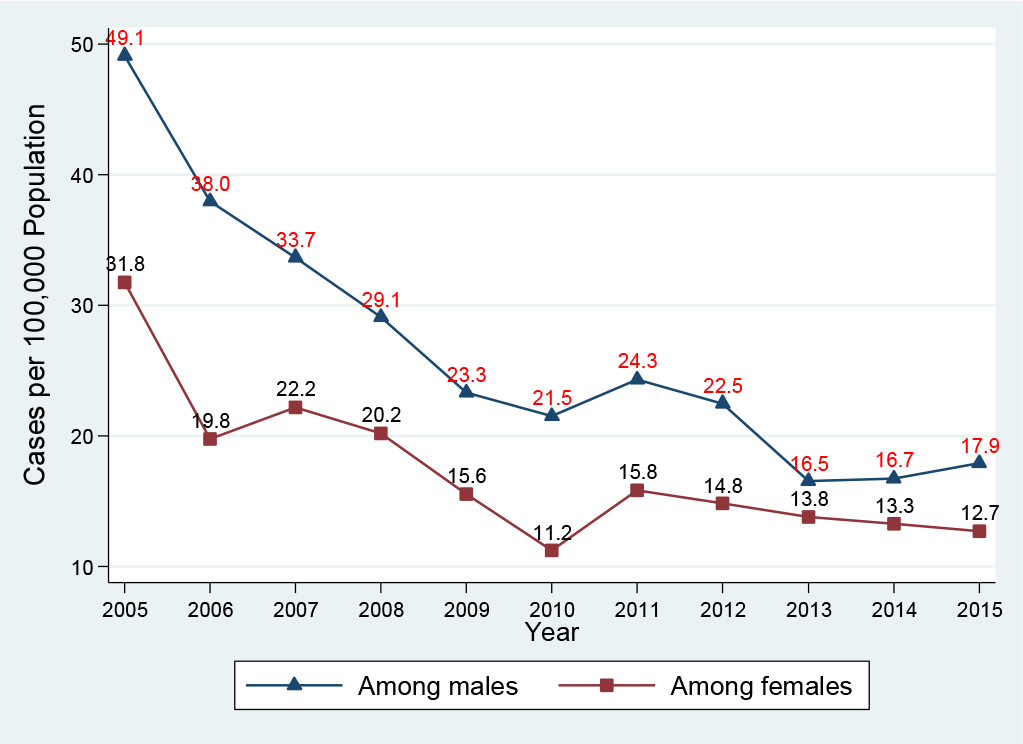

The respondent was unaware of response time being measured, being instructed simply read the vignette and assign a ‘gut-level’ judgment. Occasionally, in about 10% of the cases, the response time was longer than 10 seconds, suggesting that the respondent was doing something as well, so-called multi-tasking. Those response times of 10 seconds or longer were recoded as 10 seconds. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the 720 response times (30 respondents, each evaluating 24 vignettes)

Figure 1. Distribution of response times for the total panel of 30 respondents, each rating 24 unique vignettes.

Response time patterns for different subgroups

The measurement of response times as a key feature of Mind Genomics began during the summer of 2019. In the studies run since that introduction, the response time data suggests that when the topic deals with an important health issue, the respondents spend a long time reading the vignette, and thus their response times are long, often 1.0 seconds or longer. When the topic deals with something commercial or ‘fun’ the response times are very short, around 0.2 – 0.7 seconds.

Table 5 presents the response time coefficients for the key subgroups. The model for response time is written in the same way as the model for the binary transformed rating, with the key difference being that that the model for response time does not have an additive constant. The ingoing assumption is that the response time is 0 when there are no elements in the vignette.

Table 5. The coefficients for the response time models. The models do not feature an additive constant.

|

|

|

Male

|

Female

|

Age <50

|

Age 50+

|

Pain YES

|

Pain NO

|

Mind-Set 1: Wants a cure

|

Mind-Set 2: Simplicity through the doctor

|

|

A1

|

Pain bothers me all over my body

|

1.3

|

1.1

|

1.0

|

1.6

|

1.0

|

2.0

|

1.3

|

1.3

|

|

A2

|

The pain is localized but intolerable

|

1.0

|

1.2

|

1.3

|

1.1

|

1.1

|

1.5

|

1.0

|

1.4

|

|

A3

|

The pain radiates and makes it difficult to function

|

1.7

|

1.5

|

1.8

|

1.4

|

1.8

|

1.2

|

1.6

|

1.7

|

|

A4

|

The pain is minor but frequent and annoying

|

2.5

|

1.7

|

1.9

|

2.5

|

1.9

|

2.7

|

1.8

|

2.6

|

|

B1

|

The doctor explains to me how to deal with the pain

|

1.8

|

1.9

|

1.2

|

2.6

|

1.9

|

1.6

|

1.8

|

1.7

|

|

B2

|

I try to deal with the pain to work through it

|

2.3

|

1.6

|

1.6

|

2.1

|

2.1

|

1.5

|

2.1

|

1.7

|

|

B3

|

I’m happy when I can use a device that delivers therapeutic solution

|

2.1

|

2.3

|

1.8

|

2.7

|

2.3

|

1.8

|

2.0

|

2.2

|

|

B4

|

I just like taking a pill that deals with the pain.

|

2.0

|

1.0

|

1.1

|

2.2

|

1.9

|

0.8

|

1.4

|

1.8

|

|

C1

|

I would like to have a diet that is tailored to reduce my pain

|

1.6

|

1.0

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

1.7

|

0.5

|

1.3

|

1.4

|

|

C2

|

I would like exercises and stretches that reduce pain

|

1.2

|

0.6

|

1.2

|

0.8

|

1.3

|

-0.1

|

0.9

|

1.0

|

|

C3

|

I would like regular therapy sessions to reduce my pain

|

1.9

|

1.5

|

1.7

|

1.9

|

2.0

|

0.9

|

1.4

|

1.9

|

|

C4

|

I would like a prescription that gives me the medication I need to feel better

|

2.1

|

0.6

|

1.7

|

1.6

|

2.0

|

0.0

|

1.2

|

1.7

|

|

D1

|

The doctor should give me advice

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

1.4

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

1.3

|

1.4

|

1.6

|

|

D2

|

The doctor should give me a shot that delivers long term relief

|

1.5

|

2.1

|

1.6

|

2.0

|

1.9

|

1.5

|

1.7

|

1.9

|

|

D3

|

The doctor should set me up with a system for me to follow

|

1.7

|

2.7

|

2.0

|

2.2

|

2.0

|

2.2

|

2.4

|

1.8

|

|

D4

|

The doctor should give me a regular schedule of visits to treat my pain

|

1.7

|

1.8

|

1.4

|

2.0

|

1.8

|

1.4

|

1.3

|

2.1

|

In Table, coefficients of 2.0 or higher are shaded and shown in bold. These are the elements to which the respondent pays attention. There are some simple patterns which emerge from visual inspection of these elements that are processed ‘more slowly.’

- For gender, males focus on the description of symptoms.

A4 The pain is minor but frequent and annoying

B2 I try to deal with the pain to work through it

B3 I’m happy when I can use a device that delivers therapeutic solution

C4 I would like a prescription that gives me the medication I need to feel better

B4 I just like taking a pill that deals with the pain.

- For gender, females want a relationship, or at least someone/something external to them.

D3 The doctor should set me up with a system for me to follow

B3 I’m happy when I can use a device that delivers therapeutic solution

D2 The doctor should give me a shot that delivers long term relief

- For age, those under 50 focus on only one element:

D3 The doctor should set me up with a system for me to follow

- For age, those 50+ focus on a number of phrases, most dealing with methods to assure pain reduction

B3 I’m happy when I can use a device that delivers therapeutic solution

B1 The doctor explains to me how to deal with the pain

A4 The pain is minor but frequent and annoying

B4 I just like taking a pill that deals with the pain.

D3 The doctor should set me up with a system for me to follow

B2 I try to deal with the pain to work through it

D4 The doctor should give me a regular schedule of visits to treat my pain

D2 The doctor should give me a shot that delivers long term relief

- For pain, those with PAIN YES, i.e., who say they suffer from one or another pain, the focus is on what stops the pain, i.e., assure pain reduction

B3 I ‘m happy when I can use a device that delivers therapeutic solution

B2 I try to deal with the pain to work through it

D3 The doctor should set me up with a system for me to follow

C3 I would like regular therapy sessions to reduce my pain

C4 I would like a prescription that gives me the medication I need to feel better

- For pain, those with PAIN NO, i.e., who say that they do not suffer from pain, the focus is on descriptions of pain

A4 The pain is minor but frequent and annoying

D3 The doctor should set me up with a system for me to follow

A1 Pain bothers me all over my body

- For Mind-Sets, Mind-Set 1 (Wants a cure)

D3 The doctor should set me up with a system for me to follow

B2 I try to deal with the pain to work through it

B3 I’m happy when I can use a device that delivers therapeutic solution

- For Mind-Sets, Mind-Set 2 (Simplicity through the doctor)

A4 The pain is minor but frequent and annoying

B3 I’m happy when I can use a device that delivers therapeutic solution

D4 The doctor should give me a regular schedule of visits to treat my pain

Finding the mind-sets in the population using a PVI (Personal Viewpoint Identifier)

The mind-sets reveal different ways of perceiving the nature of pain. The mind-sets represent a way to divide what is likely a continuum of feelings and points of view into at least two distinct groups, a division which may provide further understanding, and certain a division that can be used to deal with patients in different, and possibly more appropriate fashion.

Table 6 shows, however, that it’s unlikely to identify mind-sets by their age and gender. It is also quite possible that there are no direct classifications of who a person ‘is’ or what a person ‘experiences’ which can easily assign a person to one of these two mind-sets.

Table 6. How the two emergent mind-sets for pain distribute on the self-profiling classification in terms of age, sex, and experience of pain.

|

|

Mind-Set1 Wants a cure

|

Mind-Set2 Simplicity through the doctor

|

Total

|

|

Male

|

6

|

10

|

16

|

|

Female

|

9

|

5

|

14

|

|

Total

|

15

|

15

|

30

|

|

|

|

|

|

Under 50

|

7

|

9

|

16

|

|

50+

|

7

|

6

|

13

|

|

Total

|

14

|

15

|

29

|

|

|

|

|

|

NOPAIN

|

6

|

3

|

9

|

|

YESPAIN

|

9

|

12

|

21

|

|

Total

|

15

|

15

|

30

|

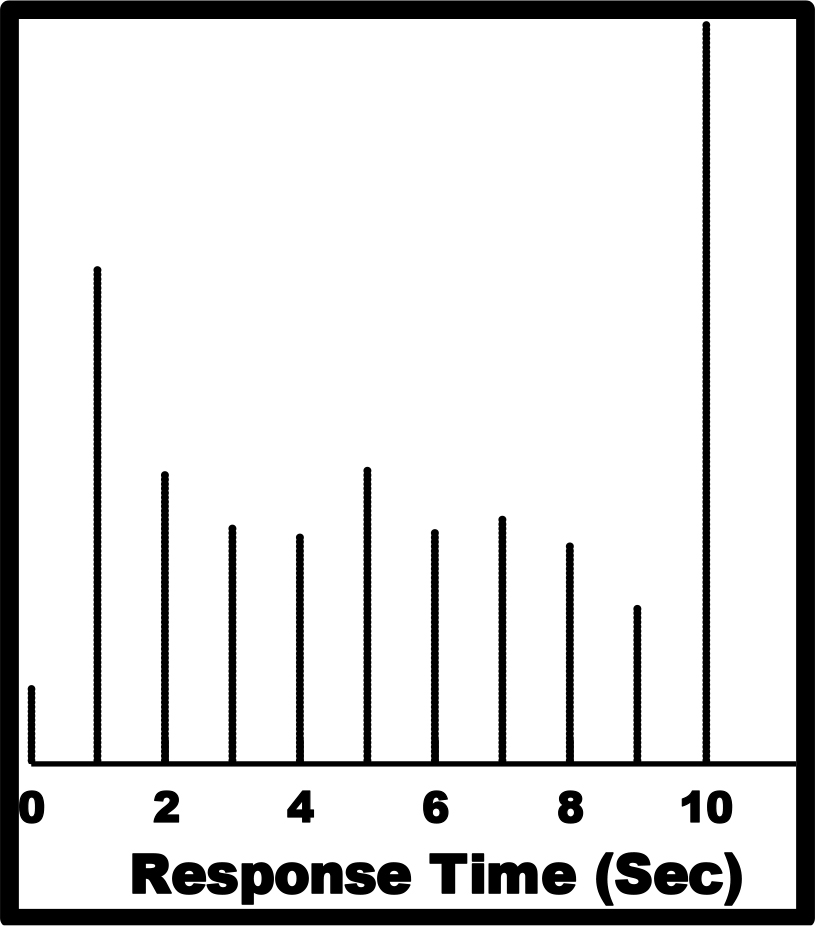

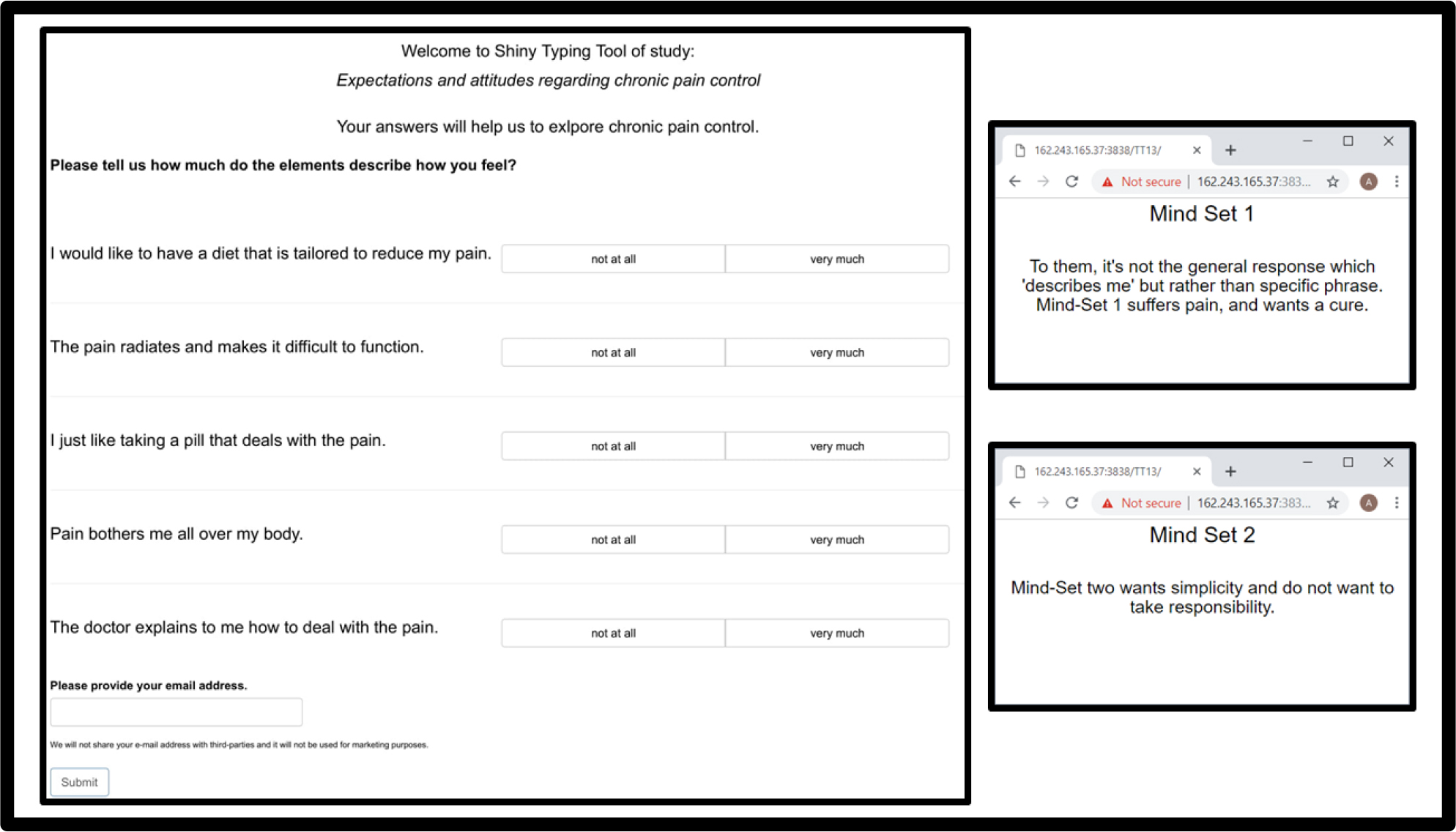

An alternative way to assign new individuals to mind-set has been developed by author Gere. It is called the PVI, the personal viewpoint identifier. The PVI comprises a set of six questions, answered with one of two answers, no or yes. The pattern of the answers to the six questions assigns the respondent to one of the two mind-sets. Figure 2 shows the PVI questionnaire at the left, and the response emerging, given either to the physician and/or to the patient/client. The questions themselves are taken from the actual study. These are the answers or elements, now turned into questions.

The PVI can be deployed along with additional information obtained during the questions. Thus, Figure 2 shows that the respondent, a new person not part of the previous study establishing the PVI, is asked for his or her email. Other questions can be asked, to relate mind-set membership to external variables, whether of a medical/health nature, or of a life-style nature.

Discussion & Conclusions

Since pain is a complex sensation involving sensory, motivational, and cognitive components, and affecting any one of these may change one’s attitudes towards pain [7]; we tested the effect of communication messaging, across mind-set segments towards pain. We tested how each min-set segment we identified emotionally responds to chronic pain, and which treatment choices are preferred by attitudinal mind-sets towards pain.

People who belong to the first mind-set segment feel the pain as radiating and challenging their daily functioning. The pain is very bothersome, but they choose to alleviate it by exercises and stretching. They chose to avoid medical treatment to simply deal with the pain and its ramifications. People belonging to the second mind-set segment also view their chronic pain as radiating and challenging their daily functioning. They, however, choose to simply take pain medication their doctor will prescribe. They expect their doctor to also set them up with a system to follow. In addition, they do not want to take responsibility for self-managing the illness which causes their pain. They prefer to avoid a diet that is tailored to reduce their pain.

Figure 2. The PVI created for the pain study. The link for the PVI as of this writing (Feb. 2019) is: http://162.243.165.37:3838/TT13/

This study also illustrated how a medical professional may easily identify the mind-set segment to which a patient belongs and accord communication messaging to patient choices and values. Identification of the mind-set to which a patient belongs may assist in building patient-physician trust resulting in higher patient adherence and better implementation of patient-centered care [21].

Mind Genomics provides the ability to segment out populations that share a common mind type and thereby help identify the possibility of determining the types of pain that a person is most likely to experience. It may help answer the question of why people with the same disease experience pain in profoundly different ways. By mind-typing patients who share ailments, Mind Genomics may aid in helping tailor a treatment plan best suited to that individual lying within a disease spectrum.

In light of the current opioid epidemic, it more important, now more than ever, to address how to customize pain treatments to individuals. There are many modalities to treat pain. In the West, pain medications are the first line of treatment. These medications include narcotics/opiates, Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, certain antidepressants, muscle relaxants, anticonvulsants, corticosteroids, local anesthetics, and most recently medical marijuana. Other modalities such as Transcutaneous Nerve Stimulation (TENS), implantable spinal cord stimulators, meditation and biofeedback are also used to help combat pain. Health care professionals who specialize in pain management use experience and training to try and help tailor treatment regimens to the individual patient. But a tool like Mind Genomics may help the practitioner go beyond the current protocols and prejudices of current practice. Mind Genomics may provide a “cheat sheet” to the patient’s mind and help provide a short cut to success by focusing on pathways that will more likely work for a given patient and eliminating the pathways that will waste time and resources.

References

- Hadjistavropoulos T, Craig KD, Duck S, Cano A, Goubert, L, et al. (2011) A biopsychosocial formulation of pain communication. Psychological bulletin 137: 9.

- Williams AC, Craig KD (2016) Updating the definition of pain. Pain 157: 2420– 2423. [crossref]

- Baker KS, Gibson S, Georgiou-Karistianis N, Roth RM, Giummarra MJ (2016) Everyday executive functioning in chronic pain: specific deficits in working memory and emotion control, predicted by mood, medications, and pain interference. The Clinical Journal of Pain 32: 673–680.

- Morrison RS, Maroney-Galin C, Kralovec PD, Meier (2005) The growth of palliative care programs in United States hospitals. Journal of Palliative Medicine 8: 1127–1134.

- Schug SA, Palmer GM, Scott DA, Halliwell R, Trinca J (2016) Acute pain management: scientific evidence, 2015. Medical Journal of Australia 204: 315–317.

- Loeser JD, Treede RD (2008) The Kyoto protocol of IASP Basic Pain Terminology. Pain 137: 473–477. [crossref]

- Atlas LY, Wager TD (2012) How expectations shape pain. Neurosci Lett 520:140–148. [crossref]

- Goffaux P, de Souza JB, Potvin S, Marchand S (2009) Pain relief through expectation supersedes descending inhibitory deficits in fibromyalgia patients. Pain 145: 18–23.

- Goffaux P, Redmond WJ, Rainville P, Marchand S (2007) Descending analgesia–when the spine echoes what the brain expects. Pain 130: 137–143. [crossref]

- Matre D, Casey KL, Knardahl S (2006) Placebo-induced changes in spinal cord pain processing. Journal of Neuroscience 26: 559–563.

- Price DD, Craggs J, Verne GN, Perlstein WM, Robinson ME (2007) Placebo analgesia is accompanied by large reductions in pain-related brain activity in irritable bowel syndrome patients. Pain 127: 63–72.

- Alkes L. Price, Arti Tandon, Nick Patterson, Kathleen C. Barnes, Nicholas Rafaels, et al (2009) Sensitive Detection of Chromosomal Segments of Distinct Ancestry in Admixed Populations. PLoS Genet 5: 1000519.

- Atlas LY, Bolger N, Lindquist MA, Wager TD (2010) Brain mediators of predictive cue effects on perceived pain. J Neurosci 30: 12964–12977. [crossref]

- Watson A, El-Deredy W, Iannetti GD, Lloyd D, Tracey I, et al. (2009) Placebo conditioning and placebo analgesia modulate a common brain network during pain anticipation and perception. PAIN 145: 24–30.

- Wager TD, Atlas LY, Leotti LA, Rilling JK (2011) Predicting individual differences in placebo analgesia: contributions of brain activity during anticipation and pain experience. Journal of Neuroscience 31: 439–452.

- Flaten MA, Aslaksen PM, Lyby PS, Bjørkedal E (2011) The relation of emotions to placebo responses. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 366: 1818–1827.

- Brand PW, Yancey P (1993) Pain: the gift nobody wants. New York, HarperCollins Publishers.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind genomics. Journal of sensory studies 21: 266–307.

- Gofman A, Moskowitz HR (2010) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127–145.

- Box GE, Hunter JS, Hunter WG (2005) Statistics for experimenters: design, innovation, and discovery (Vol. 2). New York: Wiley-Interscience.

- Gabay G, Moskowitz HR, Silcher M, Galanter E (2017) The New Novum Organum: Policies, Perceptions and Emotions in Health. Pardes-Ann Harbor Publishing.

- Moskowitz HR, Martin DM (1993) How computer aided design and presentation of concepts speeds up the product development process. Paper presented at the ESOMAR Congress, September, 1993, Copenhagen.

- Eippert F, Finsterbusch J, Bingel U, Büchel C (2009) Direct evidence for spinal cord involvement in placebo analgesia. Science 326: 404. [crossref]

- Moskowitz, HR (2012) ‘Mind genomics’: The experimental, inductive science of the ordinary, and its application to aspects of food and feeding. Physiology & behavior 107: 606–613.