Abstract

Objective of the study: Infertility affects millions of couples worldwide. Treatments have positive effects on fertility, but they also increase stress levels and disrupt emotional life. Often longer and more difficult than expected, they are a source of exhaustion and frequently cited as the cause of abandonment. The aim of this article is to evaluate the effects of a breathing control and breath hold program on stress and emotional life of patients undergoing MAP.

Method: In this randomized, single-center study, 12 MAR patients took part in a 4-week breathing control and breath hold program inspired by free diving breathing techniques, to be integrated into a care routine.

Results: Participants improved their psychological well-being in terms of stress, anxiety and depression. Negative thoughts decreased while positive thoughts increased. Sense of internal control increased positively, and quality of life improved.

Adherence to the program was very high and no side effects were reported.

Conclusion: This study tested the possibility of introducing and integrating free diving breathing techniques to help people regulate the negative impact of treatment on their emotional life. The program was very well accepted and tolerated. It met with great interest from participants and could be proposed as routine care in MPA and experimented with in other areas of mental health, such as PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder).

Keywords

Infertility, Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Breath control, Internal control, Quality of life, Emotional regulation

Introduction

Infertility affects several million couples worldwide. In France, almost a quarter of couples are unable to have children after one year of trying without contraception, and over 10% are still unable to do so after two years. In Europe, experts predict that this trend will double over the next ten years, partly due to the involvement of behavioral and environmental factors, which are increasingly suspected of affecting fertility. People eligible for assisted reproduction benefit from technical and medical advances to realize their desire for a child, but this is often at the cost of a long, difficult and psychologically challenging process. It has been observed that 40.2% of women undergoing MAP have a psychiatric disorder, the most common being generalized anxiety disorder (23.2%), followed by major depression (17%) and dysthymic disorder (9.8%). The levels of anxiety and depression observed in infertile women are equivalent to those found in women with heart disease, cancer or HIV infection [3]. However, before starting treatment, patients do not present more depressive disorders than the general population [1-6].

The percentage of couples who voluntarily abandon MAP can reach 50% after one year, and 60% after three cycles of treatment. In the opinion of couples, psychological reasons are more responsible for discontinuing protocols than medical refusal to continue attempts, physical exhaustion or medical pathologies. These abandonments are linked to emotional or psychological difficulties, anxiety and depression [7-12].

The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Psychosocial Routine Guide recommends access to psychological support [13].

Current psychological interventions aim to improve adaptation to the treatment process. A meta-analysis by Frederiksen et al (2015) showed that 56% of studies applying methods combining relaxation and cognitive behavioral therapies reduced stress and improved MPA outcome [14-16].

In either fields, studies have shown that the way we breathe influences our bodily, emotional and cognitive functioning [17-20]. Breathing has been shown to affect blood pressure, heart rate variability and certain brain regions such as the hypothalamus, amygdala and hippocampus [21,22]. Properly controlled, it helps us to regulate stress [23-25] and anxiety [26], with a reduction in cortisol concentrations in saliva. Conversely, high levels of stress have a detrimental effect on our breathing, causing hyperventilation [27-30].

Breath-holding is a special case of controlled breathing. It lies at the heart of apnea practice. The Danish national freediving team has created a respiratory rehabilitation program for patients with respiratory insufficiency. The program has met with a high level of acceptance (96.3%), while in conventional treatments, we observe patients’ difficulty in staying motivated and taking care of themselves over time [31].

It also improved exercise capacity and quality of life, with no reported side effects.

We propose to evaluate the impact of a breathing control and breath hold program, on stress for people undergoing MPA. Guillaume NERY, world champion freediver, created this specific program for the study.

Material and Method

Study Population

- This randomized study included 12 patients undergoing MPA, either as couples (female couples, female/male couples) or as singles (unmarried women). It was proposed between 05/27/2024 and 07/02/2024.

- Inclusions were entered into REDcap by the Randomization was also performed by REDcap.

- Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of no pregnancy after 12 months without contraception and societal infertility. The program had to take place before receiving hormonal stimulation treatment or between two medical protocols.

- Non-inclusion criteria were heart failure, epilepsy or pregnancy.

Intervention

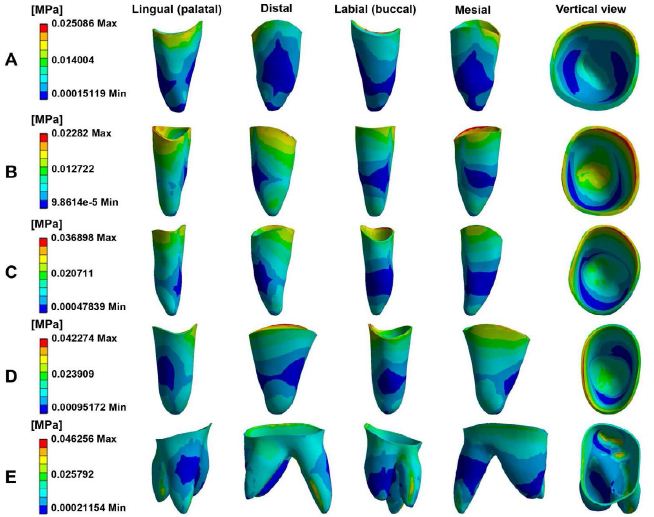

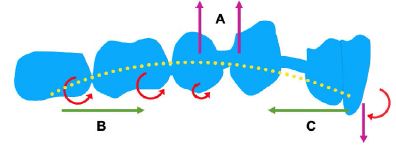

The intervention consisted of a program of breathing control and retention techniques used in freediving practice (Figure 1).

Each session lasted 1h and took place every week for 4 weeks. It consisted of:

- Introduction with a presentation of the session and a Warm up breath (observation of breath and ventilatory mechanics).

- A cycle of breath control and retention (progressive lengthening of exhalation) with body movements targeting the ribcage.

- Prolonged breath retention.

- A return to calm.

Figure 1: Program

Program Summary

This program has been proposed to patients undergoing MPA because they are confronted with high levels of stress, leading to difficult emotional elevators, a feeling of loss of control, emotional deregulation and reduced quality of life. The psychological implications are consequential in the various spheres of personal and professional life, and are a source of abandonment [7-12]. The aim was to be able to offer a stress management tool accessible to everyone, with no prerequisites and at anytime. The idea was also to propose an activity that could be shared as a couple, to create an opportunity to meet other people who live the same journey, particularly for solo women who often feel isolated in their treatment. Being able to accompany patients outside the medical treatment setting, outside the walls of the CHU (University Hospital Center) was an important point in fostering a climate of relaxation and conviviality in the AMP course. Last but not least, the aim was to accompany and support treatment protocols with a totally innovative approach.The breathing control and breath hold program was created by a renowned freediver, who is keen to pass on his practice and the associated breathing techniques to as many people as possible.

Results

Patient Characteristics

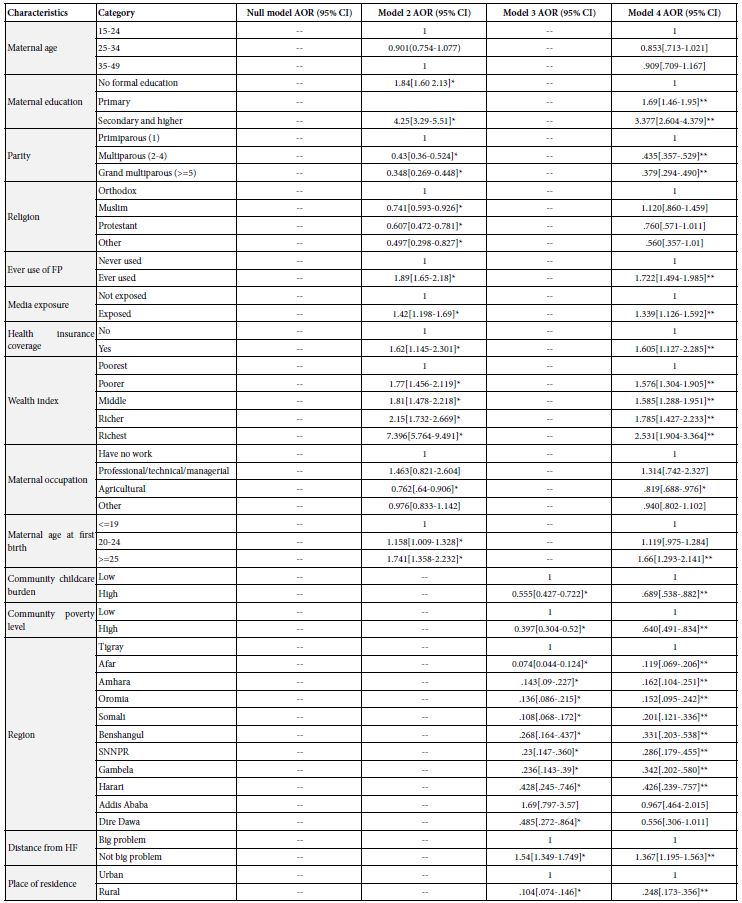

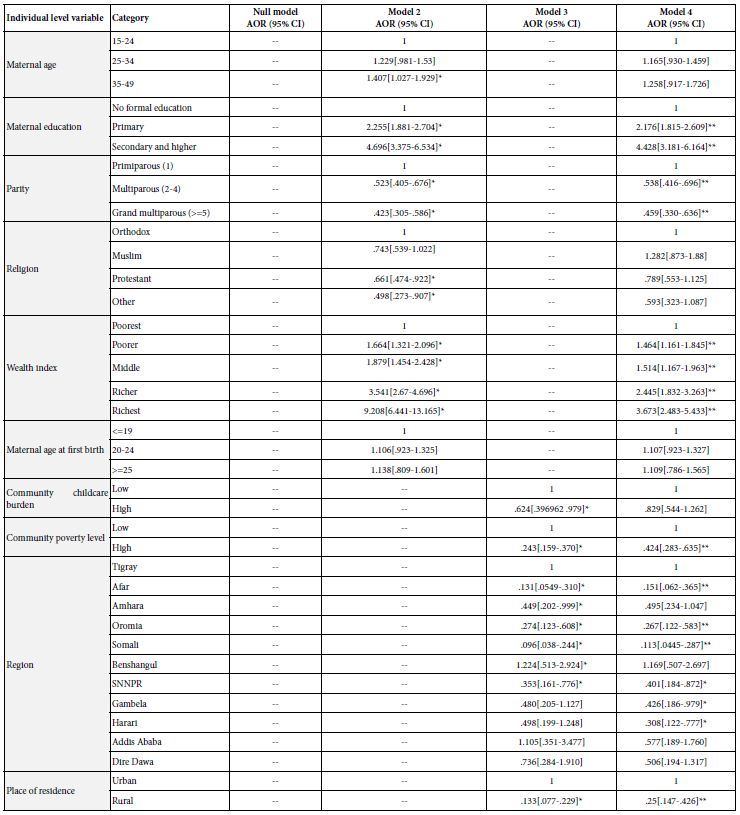

- Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

- The average age of the participants was 34.

- In both groups, almost all were women, as MPA is mainly aimed at women (solo women, female couples and female/ male couples).

- In the active group, 8 patients were couples and 4 were unmarried women.

- In both groups, all participants were working at the time of the As far as infertility is concerned, none of the participants had ever had a child. The infertility of each participant was therefore primary.

- In both groups, we observe the same distribution of 2/3 of patients in the gamete donation AMP program and 1/3 in the intra-marital program. It should be noted that half of the participants were affected by societal infertility, and therefore by gamete donation. Generally speaking, the average duration of infertility does not exceed 3 years. Only a minority in both groups had not yet received hormonal treatment.

Table 1: Characteristics of the patients.

|

Breath Group |

Control Group |

|

| Average Age |

33 |

35 |

| Female |

5 |

5 |

| Male |

1 |

1 |

| FM Couple |

2 |

3 |

| Couple FF |

2 |

1 |

| Solo Women |

2 |

2 |

| Women in Employment |

5 |

5 |

| Men in Employment |

1 |

1 |

| Infertility |

6 |

6 |

| Primary Secondary |

0 |

0 |

| Type of Fertility | ||

| Female |

2 |

2 |

| Male |

0 |

0 |

| Mixed |

0 |

1 |

| Societal |

3 |

3 |

| Societal and Feminine |

1 |

0 |

| Idiopathic |

0 |

0 |

| Conception mode | ||

| With Gamete Donation |

4 |

4 |

| Oocyte Donation |

0 |

1 |

| Sperm Donation |

4 |

3 |

| Without Gamete Donation |

2 |

2 |

| Duration of Treatment | ||

| 0-1 Year |

2 |

4 |

| 1-2 Year |

4 |

1 |

| 2-3 Year |

0 |

1 |

| >3 Year |

0 |

0 |

| No of Treatments |

1 |

2 |

| Not Yet Treated |

13 |

7 |

| Attendence at 4 Meetings |

5 |

/ |

| Study Output |

0 |

/ |

| Graduation and Participation in the program |

/ |

4 |

| Out of Sight |

1 |

1 |

Study Results

The patients in the control group, motivated by the proposed program, indicated that they wished to leave the study to take part in the program sessions. They joined the active group and completed the entire program. Comparison at M1 was therefore not possible (Table 2).

Comparison of the “Control and Breath-holding” Group and the Control Group at M0

Table 2: Main results of the emotional scales.

|

Breath Group |

Control Group | Breath Group |

Control Group |

|

|

M0 |

M1 | M0 |

M1 |

|

|

n=6 |

n=6 | n=6 |

n=6 |

|

| Stress |

21.8 |

19.8 | 17,5 |

20,5 |

| Anxiety T |

46.8 |

40.6 | 42 |

33 |

| Anxiety E |

60.8 |

43.4 | 36 |

36,6 |

| Depression |

12 |

2.8 | 5.5 |

2 |

| Positive Thoughts |

35.6 |

37 | 32 |

38 |

| Negative Thoughts |

23.8 |

20.6 | 18,5 |

19 |

| Internal Control |

11.6 |

12 | 12 |

13 |

| Control A |

9.6 |

8 | 6 |

5 |

| Control C |

8.2 |

8.8 | 7 |

7 |

| QOL Core |

64.6 |

71.6 | 67 |

68 |

| QOL Treatment |

58.75 |

62 | 100 |

68.5 |

| QOL Total Score |

92 |

82 | 58,48 |

67,5 |

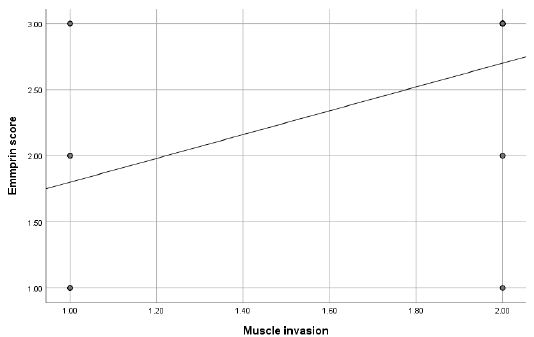

The control group is made up of 2/3 patients who will not receive hormone treatment (men or women who will not carry the pregnancy) although the “control and breath-holding” group is composed by women who’ll take the treatment at 100%.Before starting the program (M0), the control group had less stress, less treatment anxiety, fewer positive and negative thoughts, slightly more internal control, and a similar emotional quality of life. However, there were significant differences with regard to state anxiety, with rates significantly lower than those of the “control and breath-holding” group. Treatment related quality of life was significantly higher in the control group. The relationship is reversed for the overall quality of life score which is better in the “control and breath-hold” group.

For methodological reasons, the self-questionnaire scores returned by people who left the study at (M1) cannot be used. They were nevertheless reported with an improvement in parameters between (M0) and (M1).We note the positive impact of the program between M0 and M1 for the control group, particularly for depression, trait anxiety, positive thoughts and overall quality of life. When patients in the control group look ahead to treatment, however, scores drop and are lower than those in the “control and breath-hold” group.

Stress Levels

After completing the program, stress levels fell to below the pathological threshold.

Anxiety

The results show that people do not have a basic anxious personality, but they feel anxious about the medical protocol. While their habitual anxious background diminished after the program, anxiety about the treatment tended to in- crease.

Depression

A clear reduction in depressive affect was observed, with the threshold becoming almost zero at M1.

Positive and Negative Affects

The results show that patients have more positive thoughts after the program, while at the same time there is a greater reduction in negative thoughts.

Locus of Control

The patients all increased their sense of internal control over external elements, and the feeling that their actions were producing the desired effects.

Quality of Life

The results obtained show a trend towards an improvement in quality of life, at the global, emotional and treatment levels.

Program Compliance

Patients in the breathing group attended all 4 sessions, except for 1 person who was unable to attend a session for professional reasons. People in the control group left the study to take part in the breath- hold program.

Three people were lost to follow-up. They had expressed changes in their schedules shortly after signing the consent form. They did not complete any questionnaires. With the exception of those lost to follow-up, the response rate to the self-questionnaires was 100%. Patients who left the study to participate in the breathing sessions wished to complete the self-questionnaires.

Adverse Events

No adverse events were reported during the program.

Discussion

At M0, those who did not receive the hormonal treatment were less anxious about the treatment, and less depressed, than those who were to take it and carry the pregnancy. This trend is also reflected in the assessment of treatment item in quality of life, which is lower in those who will take the treatment. Treatment seems to be a factor that differentiates the two groups emotionally. Those taking the treatment will be more sensitive to emotional imbalance. On the other hand, those who do not take the treatment will be exposed to passivity. It can be hypothesized that being a “spectator” of the process represents a stress factor and a deterioration in overall quality of life, with a feeling of not being able to act concretely on the difficulties encountered by women in protocol.

Patients were sensitive to the fact that care teams were concerned about the emotional impact of treatment, and that they were offered help with an innovative activity created by a top-level athlete. Interest in and compliance with this type of program corroborates the results of a Danish study carried out by the Danish national free diving team. It proposed a respiratory rehabilitation program for patients suffering from respiratory failure. The study showed a high level of adherence (96.3%) and compliance for patients who usually have difficulty sustaining rehabilitation activities over time [31].

For infertility patients, couples wished to participate as a couple, and were very receptive and motivated by the idea of being able to share together an activity linked to their MPA journey, outside the medical context in which the man or woman who will not carry the pregnancy often finds it difficult to find their place in the journey. Only one woman in a couple did not participate with her partner, for scheduling reasons.

Those lost to follow-up expressed a lack of stability in their professional schedules (business travel, monthly schedule changes) before withdrawing.

Despite this enthusiasm, we encountered several obstacles to recruitment. Recruitment time was short (6 weeks), as sessions had to be carried out before starting the first protocol or between two protocols, and in the absence of pregnancy. Geographical remoteness was also an important factor, with the expression of excessively long travel times and the anticipation of parking difficulties. Dense or unstable schedules, compounded by numerous medical appointments, were also mentioned. In addition, patients’ availability slots were not always compatible with those of the room in which the sessions were held (mid and late afternoon times too early for most patients, who were unable to make themselves available). Finally, it was not possible to present this study to the clinical-biological team before starting the inclusions.

Raising awareness, informing and training care teams in the value of a complementary approach to limit the risks of exhaustion and abandonment in MPA could have provided a better understanding of the issues at stake in the study. Psychological burden is more difficult to bear than physiological burden. It is responsible for the majority of withdrawals from MPA, with a rate of 60% after 3 cycles of treatment.

The use of apnea breathing techniques is totally new in MPA and in the healthcare field.

Raising doctors’ awareness is particularly important, as it has been shown that the gynecologist remains the central figure in the lives of patients undergoing MPA. His word is therefore of decisive value in introducing this kind of program [32]. At an emotional level, the results of self-questionnaires show that the breath control and retention program reduces stress levels, improves psychological well- being, quality of life and feelings of internal control, and increases positive thoughts.

This trend is similar to that observed in Huberman’s study [21], which showed that, when properly controlled, breathing has significant effects on the regulation of stress, emotions and mood. The results show reduced levels of cortisol concentration in saliva and a positive impact of these breathing techniques on the hippocampus and various other brain areas, involving, among other things, an action on the vagus nerve and cardiac variability.

Similarly, he observed that voluntary breathing re-establishes a sense of control over internal states and increases positive affect. These results corroborate the trends observed in our study, whether in terms of internal locus control, positive and negative affect scale. This is particularly interesting for patients who suffer from a sense of loss of control and often dominated by negative thoughts, particularly in women after embryo transfer [33-35]. Reestablishing a sense of control could help patients regain confidence, reassuring themselves that it is possible to act on their thoughts and emotions, and that they can choose which actions to take to adapt. Better internal control will help to filter thoughts and to encourage positive ones. Patients will move from a mindset of “fighting against loss of control” to “working to control the things I can do something about”. Feeling able to act on their internal physiological and psychological state enables them to become active rather than being passive face to the treatment, to feel involved and no longer have the feeling of being subjected to treatment. In terms of anxiety, we note that trait anxiety, which relates to the treatment experience, tends to increase, while state anxiety decreases. It may be hypothesized that breath control and retention reduce general anxiety, but more practice or other tools should be considered to deal with treatment related anxiety.

The quality of life results show an improvement in overall quality of life, including emotional life and treatment experience, between M0 and M1. The medical protocols are better experienced, but they nevertheless give rise to massive anxiety, which is difficult to reduce.

Depression remains moderate at M0 and becomes almost non- existent at M1. After IVF treatment, 1 in 4 women and 1 in 10 men experience depression when the pregnancy test is negative [36- 38]. Having a regulatory tool at your disposal would help to limit depressive affects, reduce emotional elevators and better apprehend the fear of results for the next protocol.

The Breath control and breath hold program in this study is characterized by alternating sequences of breath control and retention, during which the patient moves out of his or her comfort zone, experiment phases of long exhalations, which promote a return to calm.

By focusing on the sequence of different moments, the patients live instead of experience, through the body, moments of discomfort and “challenge” during the retention phase. During the return to calm, the long exhalation repositions them in their own safety zone, fostering a sense of reassurance and confidence. It’s also interested to note that the design of a session is quite similar than MPA mental sequences. The sequence of a session includes 3Steps: a preparation of the body(before the protocol), a moment of challenge (during the protocol, action phase) with breath control and retention, and a recovery time (after the protocol). Treatment sequences follow the same triptych, with pre- treatment preparation (physical, mental, lifestyle, medical examinations), an uncomfortable period of action, during treatment, at the moment of results and afterwards, a control phase, followed by a return to everyday life and the usual balance.

Progressive preparation for the next breathing cycle allows each individual to progress at his or her own space, working on internal control and reinforcing a sense of security. At the start of the session, zone-by-zone stretching exercises prepare the body to expand the breathing space. During the session, the freediving instructor provides precise guidance, meticulously respecting the sequence and duration of each exercise. This sets a clear framework and rhythm. The freediver takes the mental load off the patient, providing warm, enveloping and deliberately minimalist guidance. The fact that there is no visualization, no mental images to suggest or elaborate, no hint of stress to evacuate, no interpretation with psychological connotations means that the patient demobilizes his mind. Patients don’t have to concentrate on memorizing breathing rhythms or program sequences. They let themselves be carried along by the voice of the freediver, who follows the program without seeking to comment or observe. The spirit of the program calms and eases the mind in favor of an intimate relationship with oneself, an active, unique and direct focus on one’s breathing body.

This mental “off-loading” is further reinforced by the fact that the instructor himself takes care of setting up and taking down the yoga mats .The duration of each breathing sequence is shared by the group. The result is a kind of “group breath” that creates a sense of unity. In this space of shared breath, everyone experiments with their own breathing rhythm and challenges, while feeling carried, accompanied, secured and supported. At the end of the program, other related benefits were observed. For example, the solo women were able to meet outside after the sessions, in a convivial atmosphere. They were able to get to know each other and share their experiences with others going through the same process. They were able to say how much these encounters had changed their experience of treatment and the precious, reassuring bonds they had forged.

Limitations

It would have been preferable to begin with a feasibility study, and to plan a training and information period with the healthcare professionals concerned before starting the study. Furthermore, randomization was carried out on an individual basis, which was a real hindrance. There was a lot of disappointments at the time of group allocation, with a feeling of failure and bad luck for those in the control group, particularly the women. It also led to people leaving the study to join their partner. As a result, the study could not be randomized.

Conclusions

This study shows that a breath control and breath hold program is an interesting stress management tool in MAR, while it can promote social bonding and improve emotional regulation. We suggest that it can be proposed as a preventive measure, by the gynecologist, to limit the risks of burn out, avoid the deterioration of the emotional state, the risks of abandonment and also multiply the chances of success. Progress must be made to take into account the psychological issues of MAR and that accompanying proposals in an integrative approach are part of the care paths. A respiratory program could be tried in other clinical fields such as PTSD (Post-traumatic Stress Disorder). This program could be considered in zoom or via an application, to broaden access, without geographical constraints or audio to do at home.

Abbreviations

MAR: Medical Assisted Reproduction; MAP: Medical Assistance for Procreation; CHU: Universitaire Hospital Center; HS: Shrinkage According Height; DS: Shrinkage According Diameter; Anxiety T: Anxiety Trait; Anxiety E: State Anxiety; Control I: Internal Control; Control A: Others Control; Control C: Chance Control; QOL Core: Quality of Life Core; QOLT: Quality of Life Treatment; QOL Total Score: Quality of Life Score Total

Acknowledgments

We thank the « Bluenery Academy and Guillaume Nery » for its contribution of this program.

Author Contributions

Valérie Benoit: Conceptualization, investigation, organization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Véronique Isnard: conceptualization, recruitment, organization. Methodology – Clémence Cirade: conceptualization, recruitment Sarah Dupuis: conceptualization, recruitment Marion Causeret: project administration, supervision

You can see full list of contributor roles below:

- Conceptualization

- Data curation

- Formal Analysis

- Funding acquisition

- Investigation

- Methodology

- Project administration

- Resources

- Software

- Supervision

- Validation

- Visualization

- Writing – original draft

- Writing – review & editing

We kindly recommend referring to CRediT Taxonomy (https://credit.niso.org/) for the detailed term explanation.

Funding

This work is supported by University Hospital Center if Nice (Grant No. XXXXX).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Rapport du Ministère de la Santé sur l’infertilité, Février 2022

- Chen TH, Chang SP, Tsai C-F, Juang KD (2004) Prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in an assisted reproductive technique clinic. Hum. Reprod 19 (10): 2313-8. [crossref]

- Domar AD, Clapp D, Slawsby E, Kessel B, Orav J, et al (2000) The impact of group psychological interventions on distress in in-fertile women. Health Psychol 19(6): 568-75. [crossref]

- Verhaak CM, Smeenk JM, Evers AW, Kremer JA, et (2007) Women’s emotional adjustment to IVF: a systematic review of 25 years of research. Hum Reprod Update 13(1): 27-36. [crossref]

- Lewis AM, Liu D, Stuart SP, Ryan G. (2013) Less depressed or less for-thcoming? Self- report of depression symptoms in women preparing for in vitro Arch Womens Ment Health 16: 87-92. [crossref]

- Lintsen AM, Verhaak CM, Eijkemans MJ, Smeenk JM, Braat (2009) Anxiety and depression have no influence on the cancellation and pregnancy rates of a first IVF or ICSI treatment. Hum Reprod 24(5): 1092-1098. [crossref]

- Domar AD (2004) Impact of psychological factors on dropout rates in insured infertility patients. Fertil Steril 81: 271-3. [crossref]

- Olivius C, Friden B, Borg G, Berg G (2004) Why do Couples discontinue in vitro fertilization treatment? A cohort study. Fertil Steril 81(2): 258-61. [crossref]

- Smeenk JMJ, Verhaak CM, Stolwijk AM, Kremer JAAM, Braat (2204) Reasons for dropout in an in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection program. Fertil Steril 81(2): 262-8

- Verhaak CM, Smeenk JMJ, Eugster A, van Minnen A, Kremer JAM, et al (2001) Stress and marital satisfaction among women before and after their first cycle in vitro fertilization and intracyto-plasmic sperm injection. Fertil Steril 76(3): 525-31. [crossref]

- Gameiro S, Boivin J, Peronace L, Verhaak CM (2012) Why do patients discontinue fertility treatment? A systematic review of reasons and predictors of discontinuation in fertility treatment. Hum Reprod Update 18(6): 652-669. [crossref]

- Cousineau TM, Domar AD (2007) Psychoogical impact of Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 21(2): 293-308. [crossref]

- S Gameiro,J Boivin, E Dancet, C de Klerk, M Emery et al (2015) ESHRE guideline: routine psychosocial care in infertility and medically assisted reproduction—a guide for fertility Hum Reprod 30: 2476-2485. [crossref]

- Balban MY, Neri E, Kogon MM, Weed L, Nouriani B, et (2023) Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. Cell Rep Med 4(1): 100895. [crossref]

- Ricou M, Marina S, Vieira PM, Duarte I, Sampaio I, et al (2019) Psychological intervention at a primary health care center: predictors of BMC Fam Pract 20(1): 116. [crossref]

- Frederiksen Y, Farver-Vestergaard I, Skovgard NG, Ingerslev HJ, Zachariae R (2015) Efficacy of psychosocial interventions for psychological and pregnancy outcomes in infertile women and men: a s y s t e m a t i c r e v i e w a n d m e t a-a n a l y s i s . BMJ Open 5(1): e006592. [crossref]

- Yackle , Schwarz LA, Kam K., Sorokin JM, Huguenard JR, et al (2017) Breathing control center neurons that promote arousal in mice. Science.355(6332): 1411-1415. [crossref]

- Feinstein JS, Buzza , Hurlemann R., Follmer RL, Dahdaleh NS, et al (2013) Fear and panic in humans with bilateral amygdala damage. Nat. Neurosci 16(3): 270-272. [crossref]

- Philippot P., Chapelle G., Blairy S. (2002) Respiratory feedback in the generation of Cognit. Emot 16(5): 605-627.. Grossman P (1983) Respiration, stress, and cardiovascular function. Psychophysiology 20(3): 284-300. [crossref]

- Jensen PS, Stevens PJ, Kenny DT (2012) Respiratory patterns in students enrolled in schools for disruptive behaviour before, during after Yoga Nidra J child Fam Studies 21: 667-681.

- Balban MY, Neri E, Kogon MM, Weed L, Nouriani B, et al (2023) Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arou-sal. Cell Rep Med 4(1): 100895. [crossref]

- Khalsa S.S, Feinstein JS, Li W., Feusner JD, Adolphs R., et al (2016) Panic anxiety in humans with bilateral amygdala lesions: pharmacological induction via cardiorespiratory interoceptive pathways. Neurosci.36(12): 3559-3566. [crossref]

- Del Negro CA, Funk GD, Feldman JL (2018) Breathing Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19(6): 351-367. [crossref]

- Rötger , Theobald DA, Abendroth J., Jacobsen T (2021) The effectiveness of combat tactical breathing as compared with prolonged exhalation. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 46(1): 19-28. [crossref]

- Bouchard , Bernier F., Boivin É., Morin B., Robillard G (2012) Using biofeedback while immersed in a stressful videogame increases the effectiveness of stress management skills in soldiers. PLoS One 7(4): e36169. [crossref]

- Zelano , Jiang H., Zhou G., Arora N., Schuele S., e al (2016) Nasal respiration entrains human limbic oscillations and modulates cognitive function. J. Neurosci 36(49): 12448-12467. [crossref]

- Ma X, Yue Z-Q, Gong Z-Q, Zhang H, Duan N-Y, et al (2017) The effect of diaphragmatic breathing on aten-tion, negative affect and stress in healthy Front Psychol 8: 874. [crossref]

- Georges Raad and others,(2021) Neurophysiology of cognitive behavioural therapy, deep breathing and progressive muscle relaxation used in conjunction with ART treatments: a narrative review, Human Reproduction Update, Volume 27(2): 324-338. [crossref]

- Grossman P(1983) Respiration, stress and cardiovascular Psychophysiology 20(3): 284-300. [crossref]

- Jensen PS, Stevens PJ, Kenny DT (2012) Respiratory paterns in students enrolled in schools for disruptive behaviour before, during, and their Yoga Nidra J Child Fam Stud 21: 667-681.

- Borg M, Thastrup T, Larsen KL, Overgaard K, Hilberg O, et al (2021) Free diving- inspired breathing techniques for COPD patients: A pilot study. Chron Respir Dis. 202118: 14799731211038673. [crossref]

- Ok TM Cousineau an SA, D Domar (2007) Psychological Impact of Best Practise and Research Clinicla Obstetrics and Gynaecology.21(2): 293-308. [crossref]

- Boivin J, Andersson L, Skoog-Svanberg A, Hjelmstedt A, Collins A, et al (1998) Psychological reactions during in vitro fertilization: similar response pattern in husbands and Hum Reprod 13: 3262-7. [crossref]

- Goacher L. (1995) In vitro fertilization: a study of clients waiting for pregnancy test Nurs Stand 10(2): 31-4.[crossref]

- Knoll N, Schwarzer R, P Fuller B, Kienle R (2009) Transmission of depressive symptoms: A Sttudy with couples undergoing assisted reproduction treatment. Eur Psychologist 14(1): 7-17.

- Boivin J, Lancastle D (2010) Medical waiting periods: imminence, emotions and Womens Health 6: 59-69. [crossref]

- Volgsten H, Skoog Svanberg A, Ekselius L, Lundkvist O, Sund-strom Poromaa I (2008) Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in infertile women and men undergoing in vitro fertilization treatment. Hum Reprod 23(9): 2056-2063. [crossref]