DOI: 10.31038/GEMS.2024654

Abstract

The paper presents the use of AI-generated ideas in a study on evaluating offers by a builder to local neighborhood regarding use of land for building new development. The novelty of the approach comes from the use of AI-generated material evaluated by human respondents, and the use of such approach to help create an efficient system to deal with local issues. The paper moves the emerging science of Mind Genomics towards dealing with the everyday problem of negotiations about civic and property issues, showing the power of AI (Idea Coach) to make the process affordable and doable in real time.

Introduction

In the ‘project of science’ research studies are assumed to emerge as efforts to contribute to a picture of ‘how the world works.’ Those who publish their investigations are often described as ‘filling gaps in our knowledge.’ Indeed, much of the edifice of science rests on the practice of what is called the ‘hypothetico-deductive’ system, the system which requires that the researcher propose a hypothesis and do the experiment to either support the hypothesis or falsify it. It is by the accretion of such studies that the edifice of science is created, the picture of the world [1]. The assumption in science is that the researcher somehow ‘knows’ a great deal about the topic and can identify what might be the next experiment to perform. The experiments often end up as simple reports, supported by statistics, and introduced by detailed literature reviews. The research ends up being done and incorporated into the edifice. At the other side of the project of science is grounded theory [2]. Here the researcher does a study or reports a set of observations. It is from those observations that hypotheses emerge. Once again, however, the effort assumes at the start that the researcher does the experiment, and thus implicitly assumes that the researcher is beginning with a knowledgeable conjecture.

What then happens in those increasingly frequent cases where the issues are new, or at least new combinations of old issues, and where there has not been sufficient time to create a literature, or even to develop grounded theory and hypotheses? Can a method be developed which allows the exploration of issues in a manner which is quick, simple, yet profound in the depths of information and insight that it can promote, and even create? This paper presents such an approach with a worked example, and a timetable of events. The topic concerns repurposing and redeveloping land in a way suitable to the existing community while allowing the developer to maximize profits.

The approach presented here, Mind Genomics, comes from a combination of three disciplines, and has evolved since the late 1990’s. The disciplines are:

- Consumer research. This area of applied science studies the way people make decisions about the topics of daily life.

- Mathematical psychology and psychophysics; The study of how we subjectively ‘measure’ external stimuli and situations in our ‘mind’, to create an algebra of the mind. For the current topic of environment and health, mathematical psychology and psychophysics will help us create the structure of how we think about topics.

- Statistics, specifically experimental design. This is the study of how we can combine different variables to represent alternative ‘realities’, these realities equivalent to different descriptions of how the world works. The normal, everyday experience of the world comes in packets of stimuli, not in single ideas. Rather than surveying the person, giving that person single questions, we create combinations of those questions, and give the person these combinations. The person then rates the combinations on a defined scale.

The issue dealt with in this paper comes from a real situation lasting several years. The issue was the sale of a large plot of land on which previously was a now bankrupt golf club. As is the case with many similar pieces of land, the golf club extended over a large area, encompassing different types of land, presenting different types of issues such as a small lake in the premises, and of course the houses that had been built in proximity to the golf course over the period of a century.

The case itself, with the different points of view espoused by local homeowners, by the local city government, and by the builder brought up the possibility that cases of this type might be amenable to study using Mind Genomics. The ingoing notion was that one could define the situation, use AI (artificial intelligence) to suggest reasonable questions and answer, and then test responses to those answer among real people. The objective was to see what would emerge from this exercise, and whether there might be an opportunity to bring Mind Genomics into an entirely new world.

Applying Mind Genomics to Legal Issues and the Law

The origin of Mind Genomics can be traced to experimental psychology, and specifically to the study of perception. After years of experiments relating physical stimuli to sensed quality and magnitude, respectively, the notion of measuring ideas began to take shape [3,4]. Researchers have long measured the strength of ideas using a rating scale, with the respondent presented with a variety of different single ideas and asked to rate each idea, one at a time, in terms of importance. This approach, the typical questionnaire, although simple to do and quite popular, does not really get at the notion of measuring the power of meaningful ideas. Rather, the questions ask for the magnitude of general classes, such as the importance of general features, e.g., the importance of affordability, the importance of ecological stability, and so forth.

At least two key issues emerge when researchers work with questionnaires.

- The misleading simplicity inherent in general questions. People live in a granular world, not in the world of the general. To talk about general aspects of an issue, e.g., service, price, and so forth, requires that the survey respondent abstract a single answer from a variety of experiences. The abstraction may be simple and straightforward, but the reality is that the survey respondent has to understand the aspect being questioned, pull up the specific experiences (unknown to the researcher), and then assign a rating to the memory of the issue or topic. In other words, no one really knows the basis on which the survey respondent is assigning the rating,

- The desire to give the right answer to the interviewer, or now to the interviewing machine. Again, and again researchers are faced with the conscious or often subconscious desire by survey takers to give the ‘right’ or the ‘politically correct’ answers. Indeed, when respondents are academics, they are often the most vocal about questionnaires, insisting that the answers be simple, so that the survey taker is not at all confused. This ends up allowing the survey taker to ‘game the system’, producing the occasionally misleading result, such as what happened in political polls with surveys about voting for a new term for then President Trump [5].

The Mind Genomics approach emerged from studies about decision making [6], not so much with the desire to avoid biases as with the desire to present to survey takers or research respondents with more meaningful test stimuli. Rather than asking the respondent to rate the single ideas, the early research efforts presented the respondents with combinations of ideas, vignettes, which presented a situation. The respondent was to either choose between two vignettes in terms of some criterion (e.g., preference) in what was called a ‘choice experiment’ (ref) or was to rate the vignette, this combination, on a scale. In either case the ratings of the choices were analyzed to show the ‘driving’ power of each individual component of the vignette. Respondents were not required to intellectualize, but simply to choose. In the Mind Genomics system, the vignettes, combinations of ideas or messages about a topic, are created according to a systematic plan called an experimental design. Rather than presenting respondents with single ideas, Mind Genomics presents the respondents with sets of ideas or elements. These messages are combined into vignettes by the experimental design in a way which allows each vignette to contain a small number of different elements, a minimum of two, and a maximum of four. In this way the vignettes are short, easy to read or more realistically to ‘scan’ as the researcher grazes across the vignette taking in the relevant information.

The Mind Genomics system creates 24 unique vignettes for each respondent or survey taker. That is, the 24 vignettes created for the first respondent are different from the 24 vignettes created for the second respondent, etc. Furthermore, the vignettes are set up so that a valid, powerful statistical analysis, OLS (ordinary least squares) regression can be performed on the results from one respondent, independent of all of the other respondents. The uniqueness of the 24 vignettes is guaranteed by a permutation algorithm [7]. The variables themselves, the elements or messages, are coded in a simple fashion, namely present or absent, called ‘dummy variable coding’ [8]. The happy result is that the researcher can identify a topic, and simply explore the topic by creating different elements or messages bout topics relevant to the topic. There does not have to be much up-front thinking. That is, the structure of the Mind Genomics design promotes exploring of different ideas, promoting experimentation and data rather than extensive army chair hypothesizing. In some quarters this up-front thinking is called ‘analysis paralysis’ … over analyzing the problem up-front before doing the experiment. In this paper we explore the use of Mind Genomics as a rapid, inexpensive tool to deal with a local problem, a problem which has proved to be fractious. The problem involves the activities of a builder in a local residential area, the building having purchased the lands belonging to a defunct golf club, the builder desirous of building single family houses on the land to maximize sales revenue after the construction. We explore how this problem can be approached by a combination of AI, artificial intelligence, to suggest ideas, and people, to evaluate these ideas.

Setting Up the Mind Genomics Study

The Mind Genomics platform uses a templated approach, the template having evolved over a 30-year span since the introduction of its predecessor, IdeaMap®, during the 1993 conference of ESOMAR in Copenhagen [9]. By templating the approach, it became possible to fulfill the objective of ‘democratizing research’ world-wide, making it possible for anyone to understand the mind of people as they make decisions about the topics of the everyday

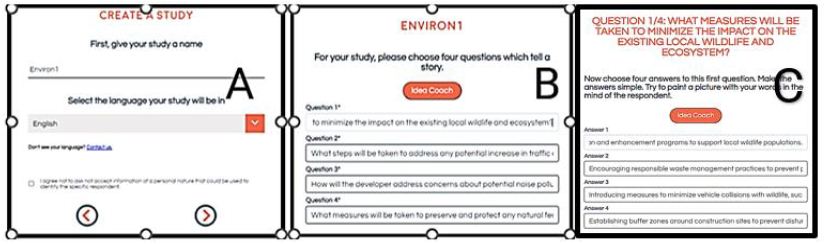

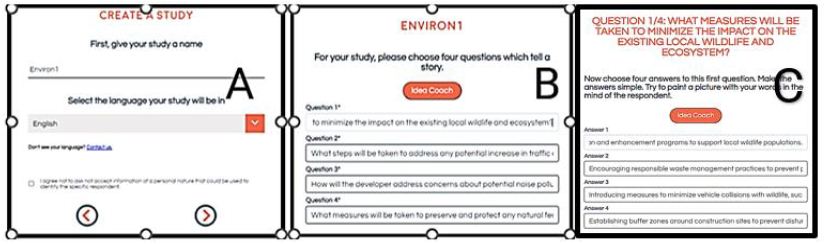

Step 1 – Name the study (Figure 1, Panel A)

‘Naming’ seems to be a simple task, but the sheer effort to reduce the research to a word or two focuses the researcher’s mind. Often the naming step turns into an exercise to hone the ‘big idea’ into something tractable, a realization which emerges after the effort is success. All too often those researchers who are new to Mind Genomics end up trying to name their study using a long phrases which ends up constraining the thinking. Forcing the researcher to use a short name opens up the researcher to thinking about the topic in a more creative fashion.

Step 2 – Develop Four Questions or ‘Categories’ Pertaining to the Topic (Figure 1, Panel B)

It is at this step that many researcher become unusually nervous as they begin to stumble about. This inability to craft questions seems endemic, across ages and cultures. It seems almost that we are taught to answer questions, but not taught to pose questions. Even seasoned researchers react with consternation and frustration at being asked to come up with four questions which ‘tell a story’, or at least four questions which end up painting a coherent picture of a topic (Figure 1).

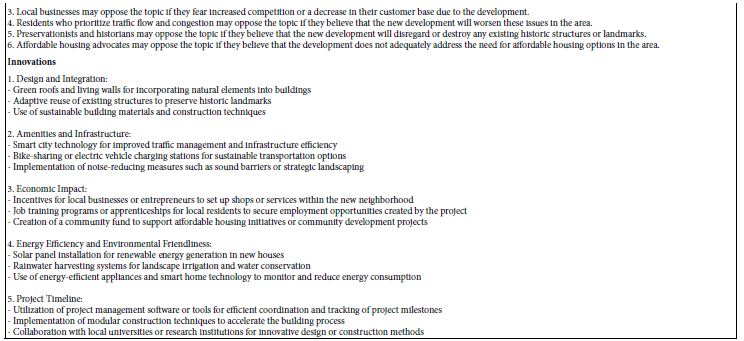

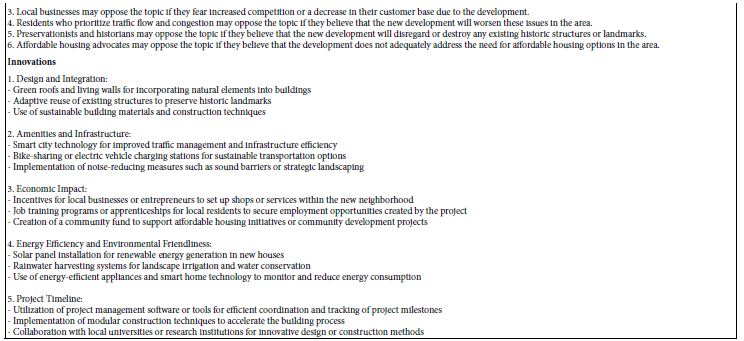

The requirement to create four questions became simpler to fulfill with the advent of available AI, specifically ChatGPT 3.5 [10]. AI was incorporated into the BimiLeap program through Idea Coach, a program specifically developed to create questions. When invoked, Idea Coach required that the research specify the topic, background, and the nature of the level of the answer. Idea Coach would then return with 15 proposed questions from which the research could select 0-4 questions and drop those questions into the study. Idea Coach allowed the researcher to modify the specification if desired, or maintain the specification, and afterwards re-run a second time. By running the Idea Coach many times, the researcher would end up creating separate sets of 15 questions, few repeating questions, but many new questions. The ability to request Idea Coach to produce sets of 15 questions was augmented by a summarizer, with each set of 15 questions separately summarized through AI. Thus, in a matter of five minutes or so, the researcher could create up to 10 different sets of 15 questions. These sets of 15 questions would be stored in an Excel workbook. At the end of selecting the questions and answers (see below), the BimiLeap program would then take each of the pages of questions or answers, 15 per page, and summarize that page with a fixed set of AI based queries. Table 1 shows an example of one page of questions, ad the Idea Coach summarization available almost immediately after program set-up. When considering the depth of information in Table 1, one can appreciate the ‘education’ virtually immediately available to the researcher who knows little about the topic, an education which otherwise might have required a year of intensive research.

Figure 1: Panel A – name the study. Panel B – create four questions Panel C – create four answers to question #1.

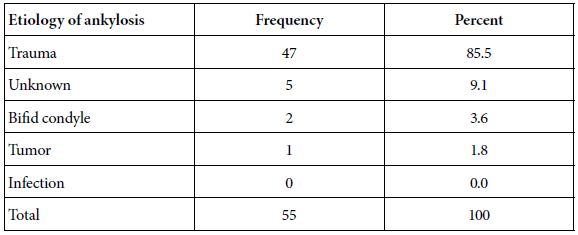

Table 1: Summarization by AI of Idea Coach’s first iteration of 15 suggested questions, generated in the effort to create four test questions for the Mind Genomics experiment.

Step 3 – Create Four Answers to Each of the Four Questions (Figure 1, Panel C)

Table 2 shows an example of 15 answers returned by Idea Coach as an attempt to answer Question #1. It is worth noting that the actual question posed to the Idea Coach moves beyond the simple question. The prompt requests that the answer ‘explain in depth’, as well as being both short (fewer than 15 words), and understandable to a 12-year-old. It is in this way that the researcher works with the AI in Idea Coach to craft a reasonable set of answers that the respondent can understand when participating in the Mind Genomics experiment. Table 2 shows both the ‘edited question’ and the first set of answers. Once again the summarizer works on each set of answers. Thus, once again the Idea Book, viz., the summarized sets of different sets of 15 questions or answers provides in 20 minutes of effort what night have taken a year or two.

Table 2: First set of answers to Question #1, followed by AI summarization of these 15 answers.

Step 4: Raw Materials Test Stimuli – Elements (Phrases Painting Word Pictures) Combined by Experimental Design

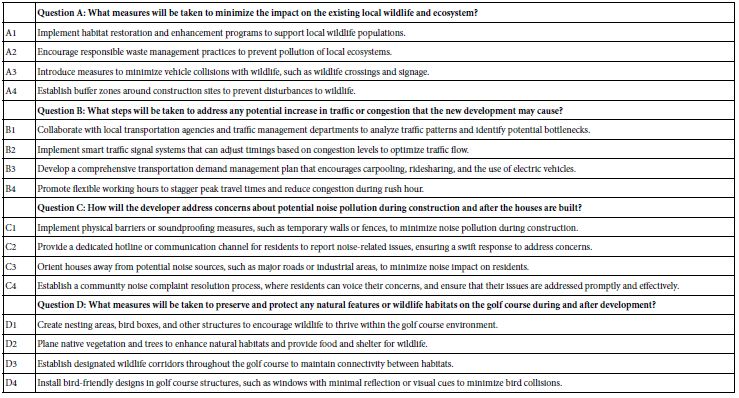

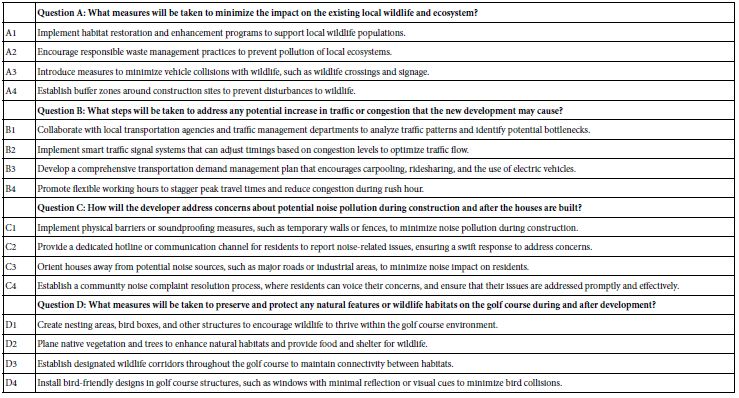

The actual raw material ends up being 16 different phrases, four selected as answers to each of the four questions. Table 3 shows these four questions and their answers. The questions and answers were generated by the combination of the researcher and the AI embedded in Idea Coach. It is important to keep in mind that the researcher is able to edit the elements at any time before the actual experiment wherein human respondents will evaluate the test stimuli.

Table 3: The final questions and their associated answers (elements).

Step 5: Create the Test Stimuli, Vignettes, Using Experimental Design

The actual stimuli rated by respondents comprise vignettes, combinations of the 16 elements. The combinations are specified by an underlying experimental design, which prescribes 24 different vignettes. Each vignette comprises a minimum of two elements and a maximum of four elements, at most one element from a question. There is no effect made to connect the elements to each other. Rather, the elements are presented in a simple, stark fashion, with one element atop the other. This starkness makes it easier for the respondent to scan the vignette and assign a rating, instead of forcing the respondent to dig through a mass of text to identify the salient messages. In author HRM’s experience, presenting respondents with complete paragraphs, connectives and all, with grammatically correct sentences ends up fatiguing the respondent by forcing the respondent to engage with the material in an effortful manner through the effort reading rather than simple inspection.

The 24 vignettes for each respondent differ from each other, as noted above [7]. This set of differences ensures that the vignettes cover a great number of possible combinations in the so-called design space, allowing the researcher to quickly explore the topic without having to know much about the topic at the beginning. Furthermore, the 24 vignettes are set up for individual-level analysis of OLS (ordinary least squares) regression, necessary when the research goal is to discover how each element drives the rating. Finally, the vignettes more naturally approach what might be experienced, because the respondent has to deal with combinations of elements and cannot game the system. There is no apparent pattern, forcing the respondent to stop looking for a pattern, and simply to respond naturally. In other words, the system frustrates the search for patterns, making the respondent guess in a fashion which seems unmotivated, but which ends up working effectively.

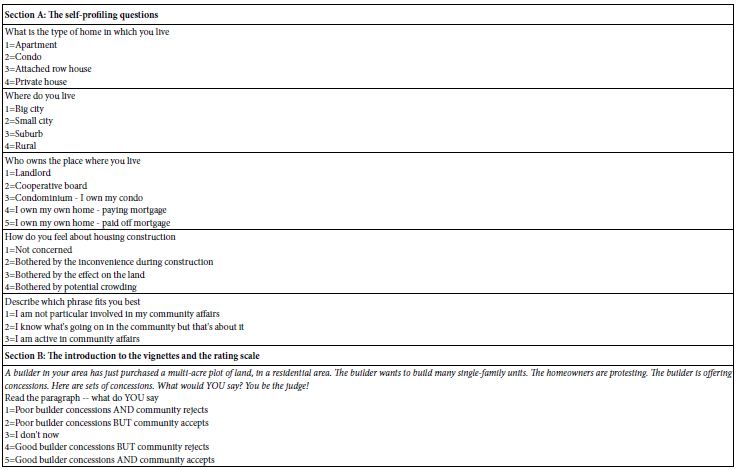

Step 6: Create a Set of Self-profiling Questions Which Allows the Researcher to Better Understand the Mind of the Respondent

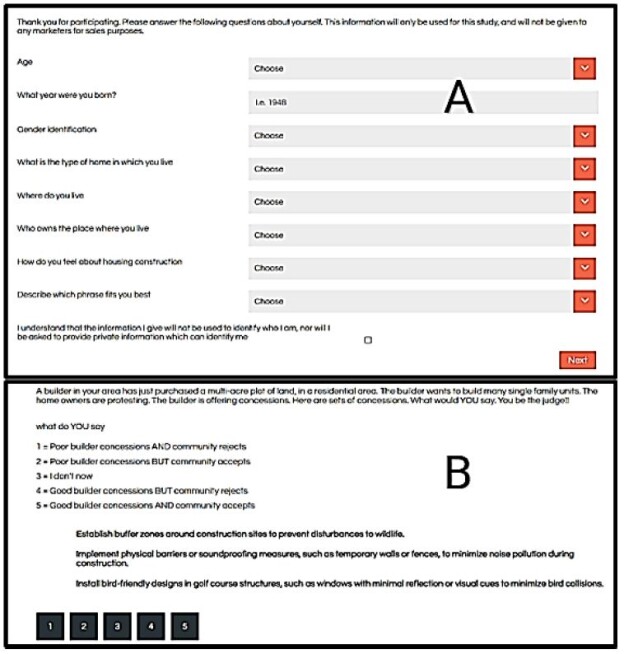

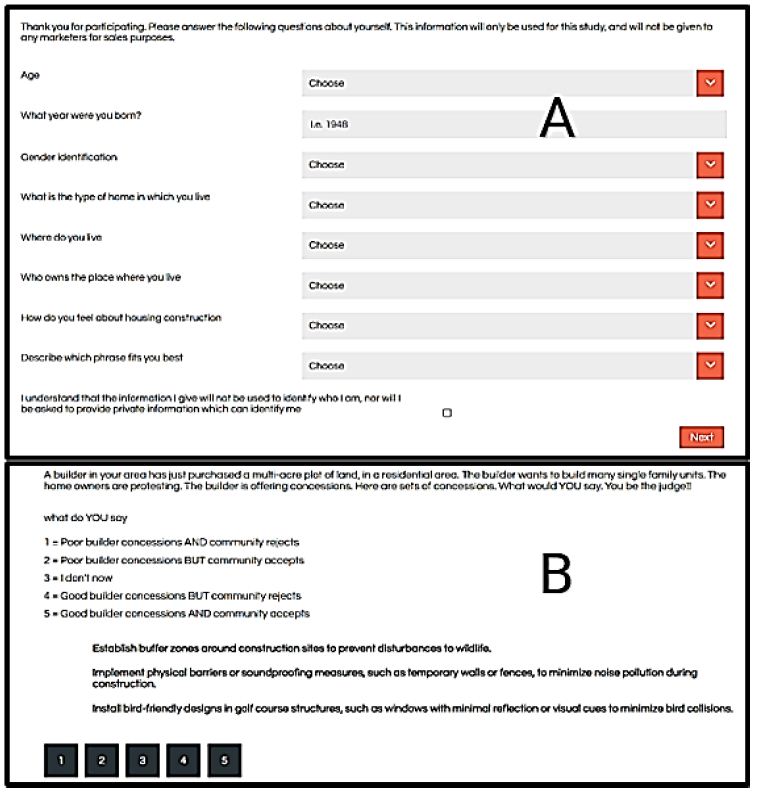

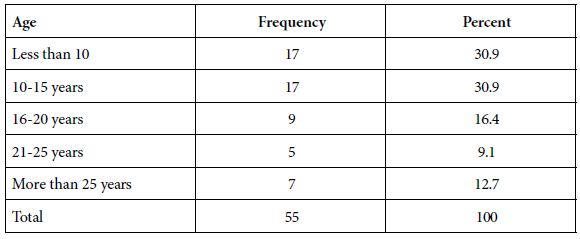

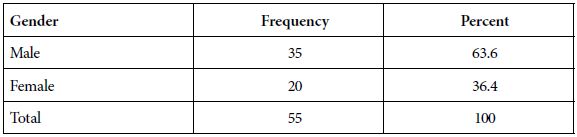

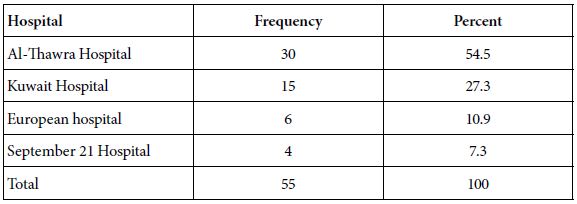

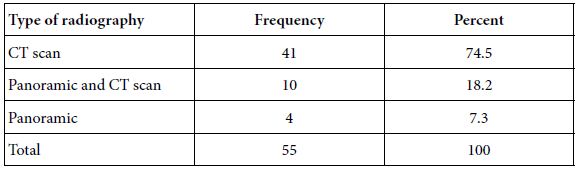

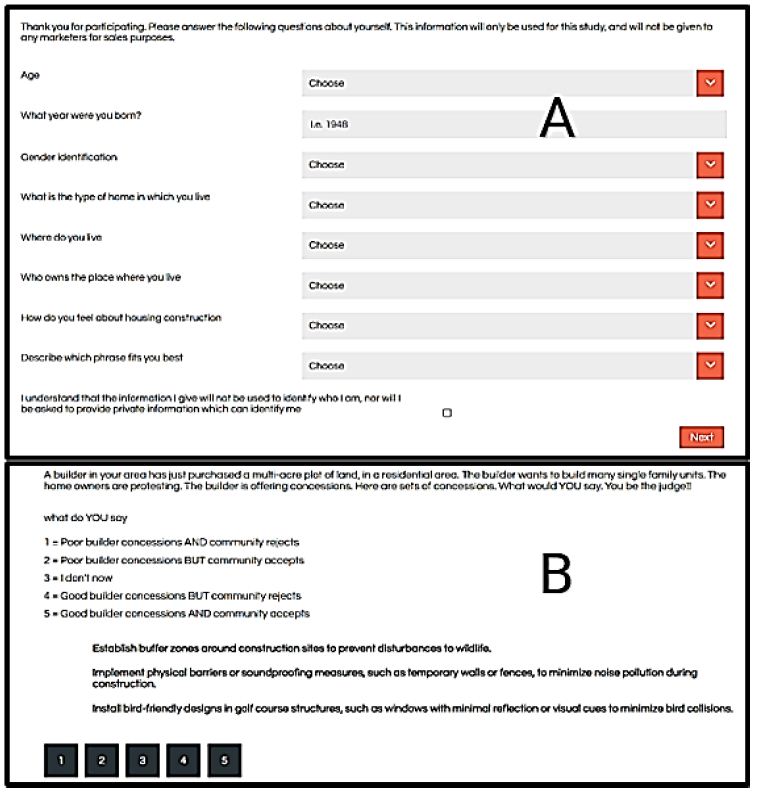

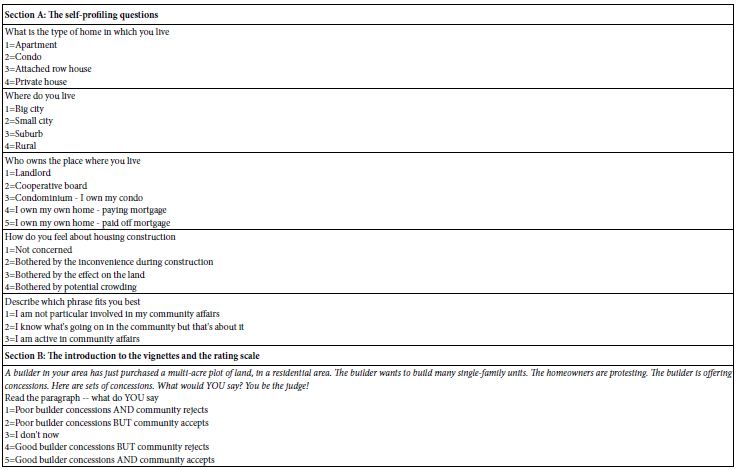

The Mind Genomics platform automatically requests the respondent to provide information about gender and age, and then gives the researcher an additional eight questions to use, each question allowing 2-8 possible answers, from which the respondent is instructed to choose one answer. In the data analyses these groups Table 4 presents these self-profiling questions and answers, along with the rating scale (see Step 7). Figure 2, Panel A shows the respondent experience when presented with these self-profiling questions, at the start of the experiment.

Figure 2: The respondent experience. Panel A – The pull-down menu for the self-profiling questions. Panel B – example of a screen showing the vignette along with the introduction and rating scale.

Table 4: The self-profiling questions (Section A), and the introduction to study topic, and the rating scale (Section B).

Step 7: Create the Introduction to the Vignettes, and the Rating Question for Each Vignette

The respondent first reads an informative introduction to the situation, and then is presented with 24 ‘screens’, each ‘screen’ comprising a shortened version of the introduction, the rating scale, and then the vignette. The rating question focuses on the mind of the respondent. It is through the rating question that the researcher will end up understanding the way the respondent thinks about the topic. The introduction and rating question appear below. Note that the rating question asks the respondent to select the answer, with the answer have ‘two sides.’ The two aspects are the nature of the concessions by the builder (good versus poor), and acceptance by the community of the concession (accepts versus rejects Figure 2, Panel B shows an example.

Figure 2: The respondent experience. Panel A shows the pull-down menu for the self-profiling question. Panel B shows an example of the short introduction to the vignette, the rating scale, and then one of the vignettes. The respondent will see 24 screens similar to Panel B, as well as a first ‘training’ screen (Figure 2).

Step 8: Collect the Data by Internet-executed Experiment and Prepare the Data for Statistical Analysis

Respondents in the New York state area were invited to participate. The respondents were to have incomes above $40,000, and 30 years or older. The respondents were members of various on-line research panels, available to Luc.id Inc., a panel aggregator. The respondents were invited by email. Those who participated pressed a link embedded in the email invitation, were led to the study, read the introduction and proceeded, first with the self-profiling questions, and then with the test vignettes.

The BimiLeap program collected the ratings and created a database. The database comprised 24 rows. Each row corresponded to one of the vignettes evaluated by the respondent. The first set of columns were devoted to identifying the study, the respondent, and the self-profiling information for the respondent, respectively. The second set of columns show the order of the vignette (1 to 24), and the composition of the vignette, expressed as 16 columns, one column for each of the 16 elements, respectively. When the element was present in the particular vignette the cell was given the value ‘1’ When the element was absent from the particular vignette the cell was given the value ‘0’. The final set of columns showed the rating, and the response time (RT) in 100ths of a second.

The data collected must be transformed for subsequent analysis by OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression [11]. OLS will relate the presence/absence of the 16 elements (Table 5) to the dependent variable.. The scale is set up to allow for several dependent variables:

R5x – good concession, neighborhood accepts. The rating of 5 transformed to 100, ratings of 1,2,3 and 4 transformed to 0.

R3x – cannot decide. The rating of 3 transformed to 100, rating of 1,2 4 or 5 transformed to 0.

R54x – good builder concession. Rating of 5 or 4 transformed to 100, rating of 1,2 or 3 transformed to 0

R52x – neighborhood accepts. Rating of 5 or 2 transformed to 100, rating of 4,3 or 1 transformed to 0.

R41x – neighborhood rejects. Rating of 4 or 1 transformed to 100, rating of 5, 3, or 2 transformed to 0

R21x – poor builder concession. Rating of 2 or 1 transformed to 100, rating of 5,4 or 3 transformed to 0.

After the transformation was made, a vanishingly small random number was added to the newly created transformed variable in order to add the needed variability to allow the OLS regression to ‘run’, and not ‘crash’. When the OLS regression encounters a dependent variable with no variability, the analysis crashes. The very small number (<10-4) is a prophylactic measure which ensures against crashes.

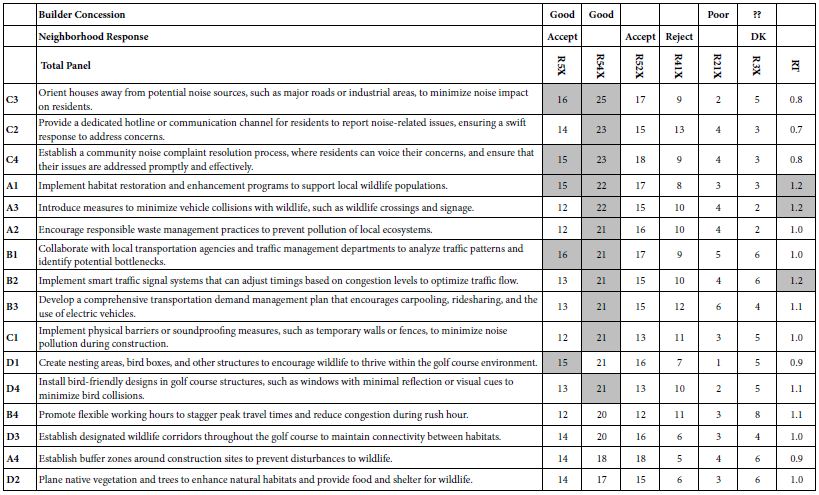

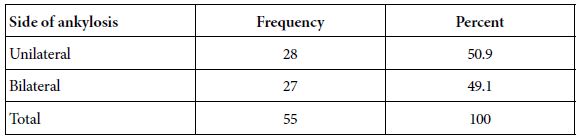

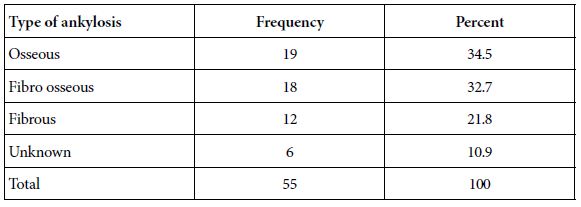

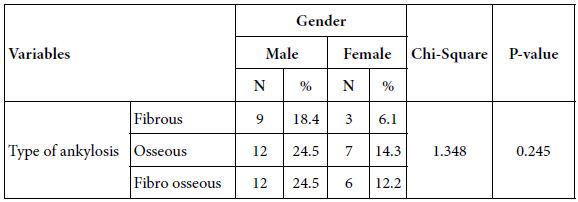

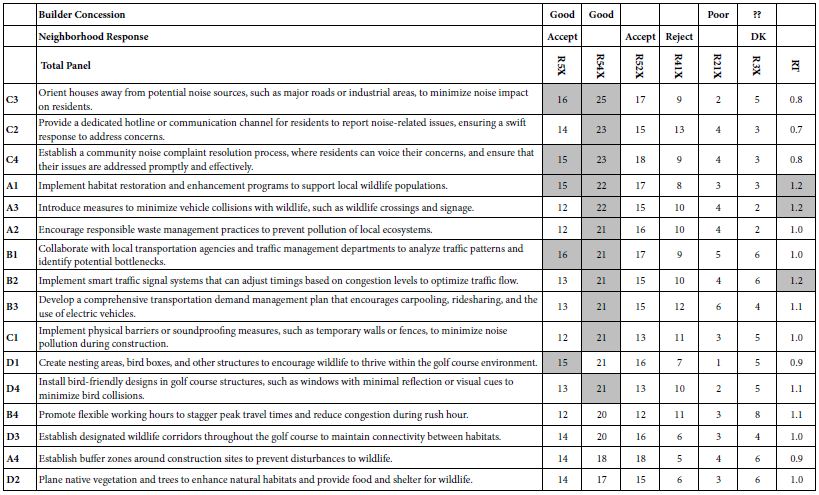

Table 5: Parameters for linear models for the total panel relating the presence/absence of the 16 elements to the binary dependent variables and to response time (RT). The elements are sorted by the coefficient for R54.

Step 9: Use OLS Regression to Relate the Presence/Absence of the 16 Elements to the Newly Created Binary Dependent Variables

The OLS regression is run on the full set of 2424 cases, 24 cases or observation for each of the 101 respondents. The equation is simple, showing the degree to which each of the 16 elements ‘drives’ the newly created binary scale, as well as how the elements drive response time.

Dependent variable = k1A1 + k2A2 +… k16D4

The equation does not have an additive constant. Previous analyses incorporated the additive constant as the 17th term of the equation. Although somewhat more statistically ‘rigorous’, estimating the additive constant created problems in the comparison of the coefficients across groups, and across studies. Analysis of the coefficients estimated with versus without the additive constant in the equation showed that the coefficients were of different values, as expected, but strongly and positively correlated with each other. Strong performing elements were strong whether estimated with an additive constant or without an additive constant. Table 5 shows the coefficients for the different binary dependent variables, and the response time. The top of Table 5 shows the meaning of the dependent variable. For this study, the key dependent variable will be R54x, a good concession from the builder, but it is instructive to consider all of the binary dependent variables and the response time. Most concessions offered by the builder were seen to be positive. Coefficients for R54 equal or greater than 21 are shown in shaded cells. Despite the strong performance of most elements, however, there is no sense of a pattern in the mind of the respondents. The coefficients are close together, hovering around 21, some coefficient lower, some coefficients higher.

Table 5 shows a ‘flatness’ of rating value across the elements. Of course, in the absence of anything else the researcher could simply look at the strong performing elements, and stop there, listing out these elements, as well as listing the. Table 5 does not reveal a clear relation between strength of performance and long response time.

Uncovering Different Ways of Thinking about the Topic Through Mind-set Segmentation

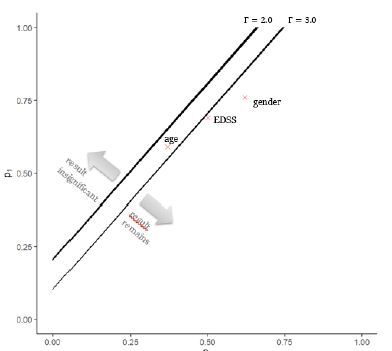

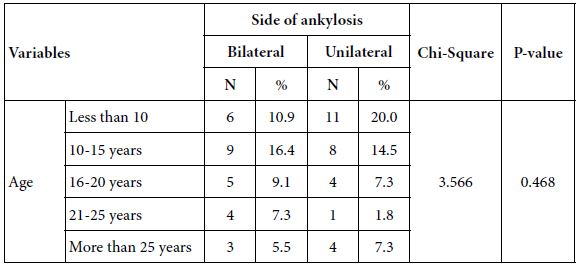

A hallmark of Mind Genomics is that people differ from each other in the way that they think about a topic, with these different ways not necessarily being random person to person variation. Rather, many studies suggest that when it comes to the topic of the everyday world, people’s different opinions about aspects of the topic appear to form clearly distinct groupings, mind-sets in the language of Mind Genomics, clusters in the language of statistics [12]. These differences in the way people think about topics is clear when we deal with products, especially food, but also many of the products and services that we purchase and consume [13]. The differences emerge in responses to social issues, and clearly emerge in the law, except perhaps for one topic, murder, where these mind-sets do not seem to loom large [14]. With the prevalence of mind-sets in the population, can we find these mind-sets in the population of our 101 respondents who are dealing with the issue of their response to builder concessions with regard to building of a community of stand-alone houses in a community. The large number of high positive coefficients for the 16 elements in Table 5 (Total Panel; R54x) presents us with an interesting possibility, namely that all of the elements are positive, viz., that all of the builder concessions appear to be good ones. Faced with this somewhat flat distribution of coefficients from a low of +17 to a high of +23 for R54x (good concession), will this case of builder concession become an example of how there are no clear mind-set?. The possibility is certainly real. Nothing dictates that every issue should comprise within it radically different mind-sets. Attitudes about builder concessions may be shared by all people. Table 6 shows the outcome of clustering the 101 respondents, first into two clusters or mind-set, then into three clusters or mind-sets. The method of clustering, k-means, divides the 101 respondents by the pattern of their 16 coefficients. The distance between any two respondents is defined as (1 – Pearson R, or correlation coefficient). The Pearson R ranges between a value of 1 when two sets of objects, e.g., coefficients, align perfectly, viz. are parallel, going in the precise same direction, and a value of -1 when two sets if objects move in opposite direction. The k-means clustering technique is purely mathematical, attempting to satisfy several criteria at the same time [15].

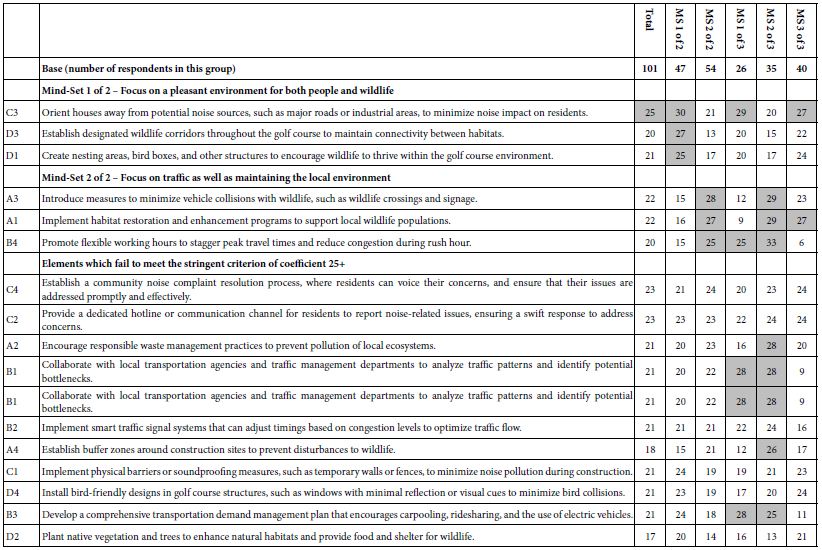

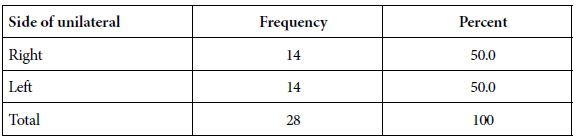

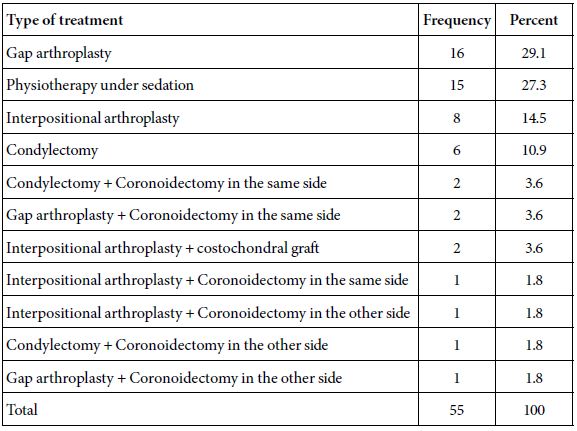

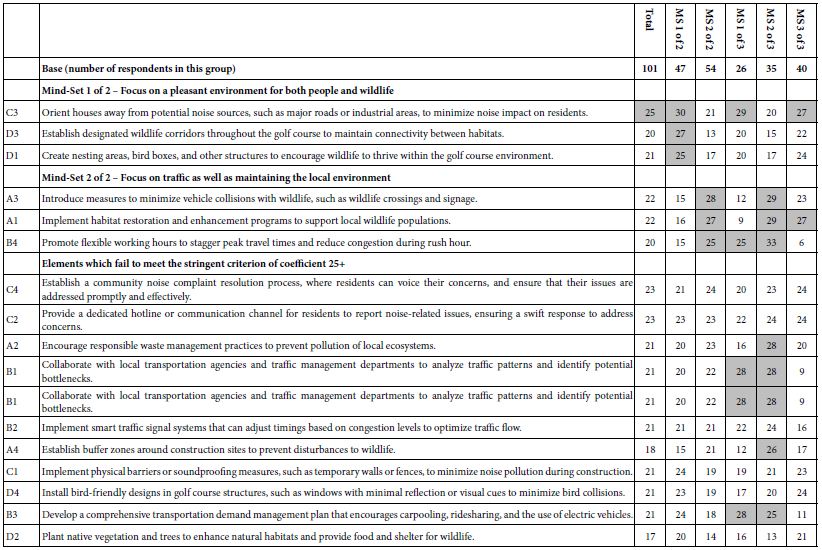

Table 6: Results from the segmentation of respondent on the basis of R54x, builder provides good concessions. The criteria for ‘strong performing’ element has been increased from the conventional value of 21 to a more stringent value of 25+ in order to allow for clearer definition of the nature of the mind-sets.

The clustering was done on the coefficients for R54, viz., perception that the builder concessions are good. One could also do the clustering on the basis of R52, acceptance of the builder concessions, but for this paper we focus only on R54x. Table 6 shows a great number of positive coefficients, magnitude 21+. The coefficient value of 21 may be too lenient a criterion. In Table 6 we highlight the coefficients of 25+, making the criterion more stringent. The two-mind-set solution can be more easily interpreted than the three-mind-set solution. With this more stringent criterion in place the mind-sets may be interpreted as:

Mind-Set 1 of 2 – Focus on a pleasant environment for both people and wildlife

Mind-Set 2 of 2 – Focus on traffic as well as maintaining the local environment.

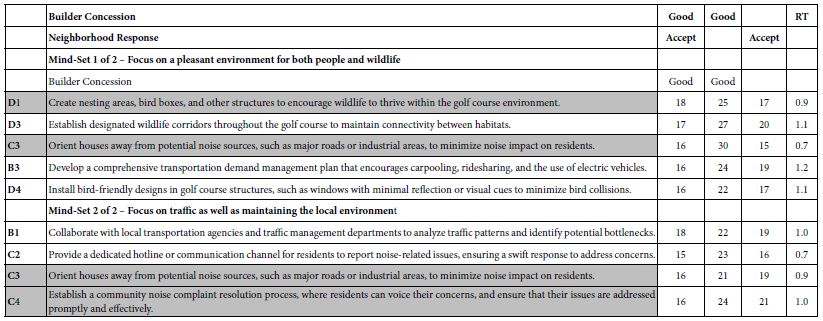

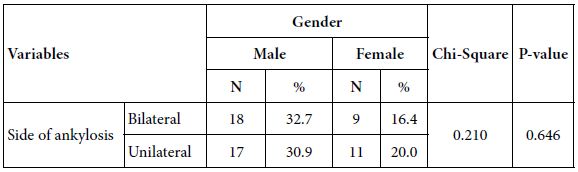

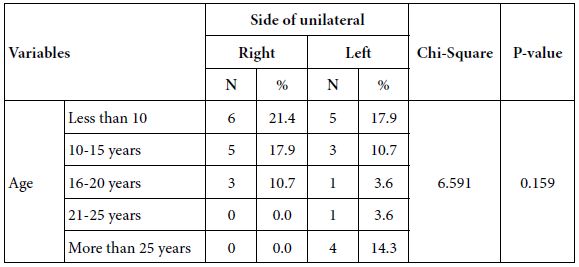

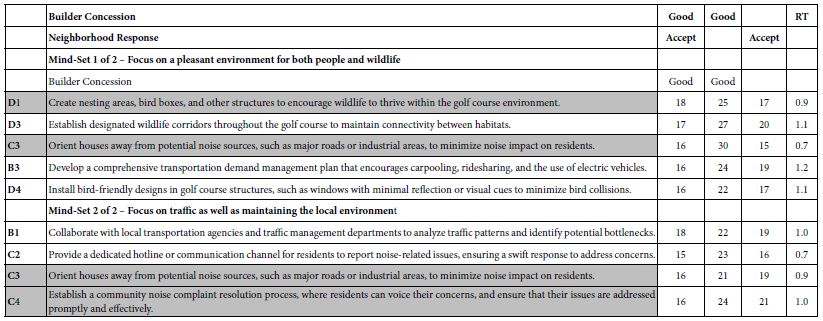

Coming to an Agreement

The relative flatness of the data in terms of range, along with the strong performance of many of the elements in terms of how good the respondents feel about the builder concessions generates a situation not typical to Mind Genomics. For most topics dealt with in previous studies, the experiment presented above have shown clearly different mind-sets. Perhaps the only case where there has not been clear and strong differences between or among mind-sets has been the case of murder [14]. Yet, here we have the situation of most elements being positive. The issue now evolves to selecting the best element from the total panel, C3. Orient houses away from potential noise sources, such as major roads or industrial areas, to minimize noise impact on residents. The wisdom of selecting C3 is confirmed by listing the strong performing elements for both mind-sets, as is done in Table 7. The table shows the strong performing elements for both mind-sets. C3 is common to both mind-sets and thus should be the key concession accepted by the local community. In addition, the negotiation might consider two other requests from the builder, in order to satisfy the two mind-sets:

Mind-Set 1: D1 Create nesting areas, bird boxes, and other structures to encourage wildlife to thrive within the golf course environment.

Mind-Set 2: C4 Establish a community noise complaint resolution process, where residents can voice their concerns, and ensure that their issues are addressed promptly and effectively.

The benefit of a Mind Genomics experiment in this case emerges as a way to find ‘second best’ ideas that will work for the different mind-sets.

Table 7: Selecting the best single concession (C3) and one additional concession to satisfy each mind-set more deeply.

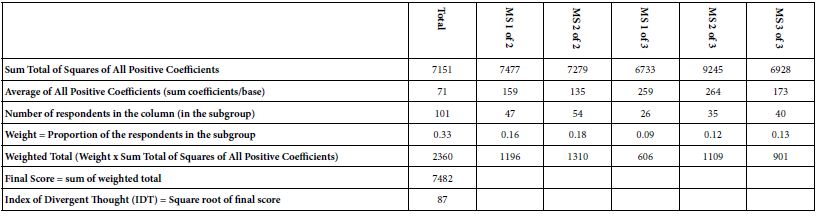

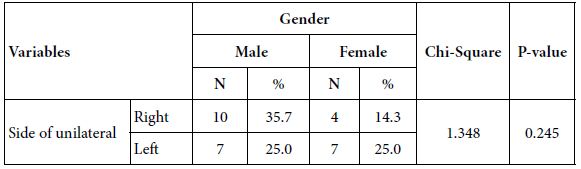

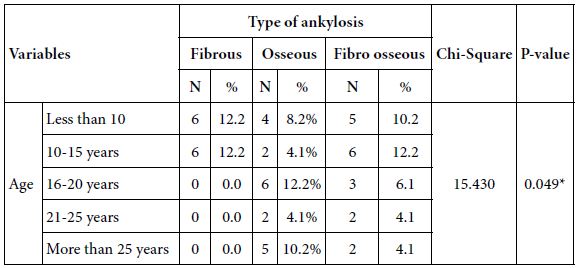

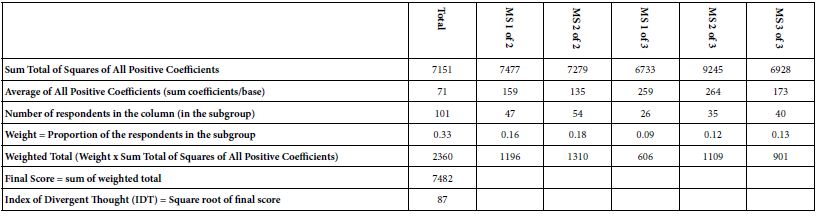

How Good are the Ideas the Ideas – Index of Divergent Thought (IDT)

A continuing issue in Mind Genomics revolves around the topic of the elements, specifically are the elements ‘good’ or ‘poor’. This question is relevant, indeed increasingly so, as the ability of people to think critically seems to be diminishing. Certainly, the pre-AI days showed that the effort to create four questions ended up being a frustrating experience, and a clear stumbling block to the use of Mind Genomics. It was only after the introduction of AI in the form of the Idea Coach that the task became easier. Let us now merge the use of AI with the specific topic dealt with here, viz., the issues regarding the concessions offered by a builder. The elements were developed in conjunction with AI. The data suggest a large number of strongly positive elements. In order to quantify the true strength of the ideas, a computational method should be developed which accounts for the strength of the elements, as well as the proportion of the population among which the elements perform strongly. Thus, the underlying ‘thinking’ becomes much more impressive when the elements perform strongly, viz., have high coefficients, with large groups in the population. In contrast, when elements perform strongly, but only among a small size group of respondents in the population, we can say that the thinking is not quite as good. Table 8 shows the computations leading up to the IDT, the index of divergent thought. The IDT provides one empirical way to measure the strength of performance. The IDT ends up being the square root of the weighted sum of square of all the elements with positive coefficients, across six groups: total panel, the two mind-sets, and the three mind-sets, respectively. Typical results in the past have ranged from a low near 55 and a high near 75. The 87 generated in this study suggests that the thinking is particularly good, perhaps aided by the fact that the strong performing elements because there are no counter-current patterns generated by mind-set with opposing ideas. That is, the basic ideas are good, that good performance reinforced by the similar patterns of mind-sets which differ only slightly from each other.

Table 8: Computation of the IDT, Index of Divergent Thought.

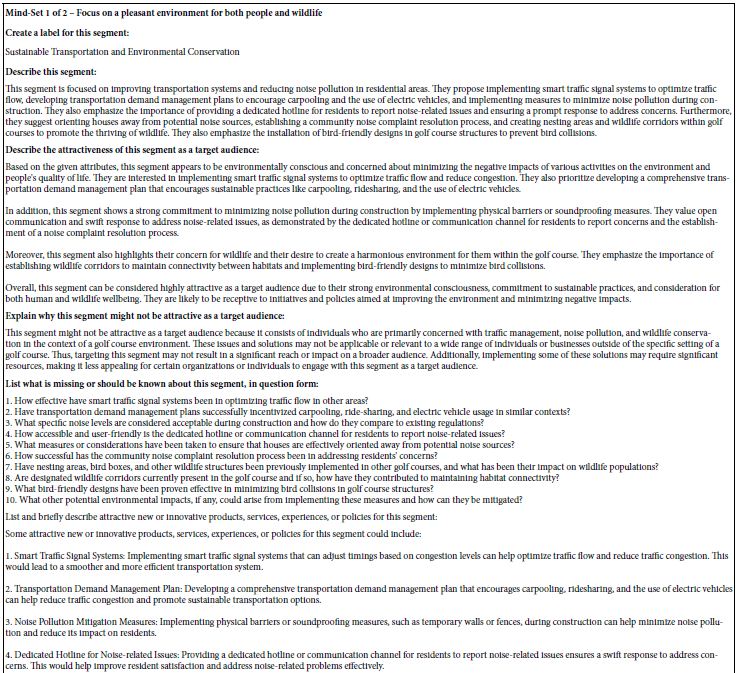

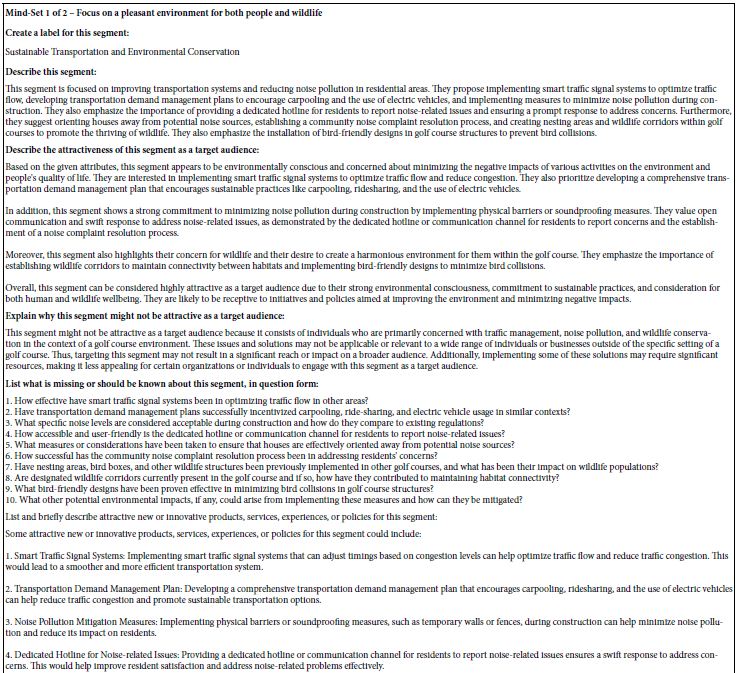

Deeper Thinking about Mind-sets for R54 (Good Builder Concessions) Using AI Summarization

The final analysis for this rich set of data regarding a local community issue comes from the AI summarization of the strong performing elements for R54 (good builder concessions), done for the two mind-sets. Table 9 shows the summarization, based upon a series of queries submitted to AI (Idea Coach), which looked only at the elements with coefficients of 21 or higher for the mind-set, for dependent variable R54. The AI provides the researcher with what ends up being a ‘second pair of eyes.’

Table 9: AI summarization of the strong performing elements for the two mind-sets, based upon the coefficients for R54 (Good concession from the builder).

Do Open Ended Comments Give Any Deeper Insight into the Mind-sets

After the respondent finished rating all 24 vignettes, the respondent was presented with the instruction to answer the following question by writing one or more sentences: How does being a judge about this negotiation between builder and community make you feel? Table 10 shows the AI summarization of the open ends, with slight editorial changes by the authors to make the summarization more relevant to parties in a negotiation. The summarization was done by QuillBot, an AI editor [16]. The differences between the mind-sets emerge in Table 10, but once again the differences are a matter of ‘shading’ rather than of radically different points of view.

Table 10: AI summarization of the open-ended question.

Discussion and Conclusions

The goal of this paper, dealing with a local property development issue, represents a new direction for Mind Genomics, one perhaps frequently encountered in legal and professional circles, rather than in research papers. The original efforts of Mind Genomics were based in the effort to understand the preferences of people for the ‘stuff’ of everyday life, whether products or services. The almost universal finding from all of the Mind Genomics experiments was the emergence of a limited number of clearly defined mind-sets. When the research moved to political polling [13] or to social research of serious problems [17] clearly different mind-set once again emerged. It is only with problems of the local community that we see the absence of such strong mind-sets. The mind-sets do emerge, as they must with statistical processing forcing them out of the data. However, the mind-sets are similar to each other in the response to most of the messages. It is only the ‘shading’ of the responses where we find differences, and where we struggle to come out with these different groups. The subtlety of point of view of such issues has already been recognized, although not in the language of Mind Genomics [18-22]. As we go through these results, the question now emerges as to how to treat differences of opinion in the situations where the mind-sets reflect modest quantitative differences, shadings of opinion rather than striking differences. It may well be that in many situations dealing with negotiations, the different offerings brought by the parties are almost all equally acceptable. In such cases Mind Genomics may reveal an entirely new opportunity to study the way people make decisions, not so much in the world of preference patterns but rather in the world of graduated ‘give and take’, the world of subtleties in negotiation, rather than dramatic differences in thinking about a topic.

References

- Lawson AE (2000) The generality of hypothetico-deductive reasoning: Making scientific thinking explicit. The American Biology Teacher 62: 482-495.

- Seyfi S, Michael Hall C, Fagnoni E (2019). Managing world heritage site stakeholders: A grounded theory paradigm model approach. Journal of Heritage Tourism 14: 308-324.

- Moskowitz HR (2012) ‘Mind Genomics’: The experimental, inductive science of the ordinary, and its application to aspects of food and feeding. Physiology & Behavior 107: s 606-613.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind Genomics. Journal of Sensory Studies, 21: 266-307.

- Kennedy C, Blumenthal M, Clement S, Clinton JD, Durand C, et al. (2018) An evaluation of the 2016 election polls in the United States. Public Opinion Quarterly 82: 1-33.

- Porretta S, Gere A, Radványi D, Moskowitz H (2019) Mind Genomics (conjoint analysis): The new concept research in the analysis of consumer behaviour and choice. Trends in Food Science & Technology 84: 29-33.

- Gofman A, Moskowitz H (2010) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127-145.

- Hardy MA (1993) Regression with dummy variables (Vol 93). Sage.

- Moskowitz HR, Martin D (1993) How computer aided design and presentation of concepts speeds up the product development process. In ESOMAR Marketing Research Congress. Pg: 405.

- Teubner T, Flath CM, Weinhardt C, Christof Tl. (2023) Welcome to the era of ChatGPT, the prospects of large language models. Business & Information Systems Engineering Pg: 95-101.

- Craven BD, Islam SM (2011) Ordinary least-squares regression. The SAGE Dictionary of Quantitative Management Research. Pg: 224-228.

- Talevich JR, Read SJ, Walsh DA, Iyer R, Chopra G (2017) Toward a comprehensive taxonomy of human motives. PloS one 12. [crossref]

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A (2007) Selling Blue Elephants: How to Make Great Products That People Want Before They Even Know They Want Them. Pearson Education.

- Moskowitz HR, Wren J, Papajorgji P (2020) Mind Genomics and the Law. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

- Pham DT, Dimov SS, Nguyen CD (2005) Selection of K in K-means clustering. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science 219: 103-119.

- Fitria TN (2021) QuillBot as an online tool: Students’ alternative in paraphrasing and rewriting of English writing. Englisia: Journal of Language, Education, and Humanities, 9: 183-196.

- Zemel R, Attila Gere, Petraq Papajorgji, Howard Moskowitz (2019) Young Americans reacting to statements about Palestine & Israel: A Mind Genomics exploration. Ageing Science and Mental Health Studies, 3: 1-12.

- Pacione M (2013) Private profit, public interest and land use planning—A conflict interpretation of residential development pressure in Glasgow’s rural–urban fringe. Land Use Policy, 32: 1-77.

- Pinto Â, Pinto T, Praça I, Vale Z, Faria P (2018) Clustering-based negotiation profiles definition for local energy transactions. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Control, and Computing Technologies for Smart Grids (SmartGridComm), October, 1-5.

- Song Y, Knaap GJ (2007). Quantitative classification of neighbourhoods: The neighbourhoods of new single-family homes in the Portland Metropolitan Area. Journal of Urban Design 12: 1-24.

- Stevens SS (2017) Psychophysics: Introduction to its perceptual, neural and social prospects. John Wiley.

- Joshua MDuke(2004)Institutions and land-use conflicts: Harm, dispute processing, and transactions.Journal of Economic Issues 38: 227-252.