Infectious Diseases and Therapeutics

Monthly Archives: June 2024

Mind-Sets of “Verbal Judo” – How Young Males Respond to Described Interactions between Perpetrators and Police Officers

DOI: 10.31038/ALE.2024111

Abstract

The study focuses on how young males, ages 16-30, in the Virginia area respond to different scenarios of a police officer interacting with a prospective lawbreaker. The scenarios were created by systematic combinations of messages (elements), developed from human experience and artificial intelligence. The deconstruction of the ratings into the part-worth contribution of each of 16 elements showed the degree to which each element would be “listened to” by the prospective lawbreaker, as well as the degree to which the same element would lessen the anger. Three mind-sets emerged. The first mind-set is the police officer who creates empathy, which de-escalates the situation. The second mind-set is the take-charge officer, who clearly senses a developing problem, talks authoritatively. The third mind-set pays attention to community-oriented and empathic policing. These mind-sets represent the way ordinary people, young males, think about the police and what the police do when they read about these different potential crimes and interactions between perpetrators and police. The approach allows us to identify the way young people think about the information that they read. The results show that not everybody is the same and that there may be different strategies about the role of police officers depending upon the nature of that to which a person pays attention.

Keywords

Lawbreaker, Mind-sets, Police officer, Verbal judo

Introduction

The origin of this study can be traced to ongoing work by the authors in the world of working with police officers to figure out how to deal with the public, how to deal with active lawbreakers, prospective lawbreakers, situations which may turn violent, and finally, just as important, how to recruit police officers in a world where certain kinds of social activities have been set up to hamper police officers. The study that was done here concerns what the police officer should say to an individual who looks like that individual will engage in violence. The study is based upon a series of discussions with various police departments, as well as the recognition that there are different mind-sets of criminals. A detailed look through the literature of crime suggests that criminals, those who do violence for example, are not doing it all for the same motive [1-5]. This statement may seem like a truism, and it is to some extent. However, the ramifications of this truism are especially important. We are not dealing here with academic issues which will result in the same outcomes. Rather, we are discussing real-world situations in which violence may take place, in which people may get hurt or even killed. We are looking at a problem which is systemic all over the world, namely the interaction, and perhaps even confrontation, between a police officer and a lawbreaker. Crimes are committed for different reasons. What’s not necessarily obvious is the nature of the motivation of the criminal, and perhaps just as well, the type of communication to which the criminal or at least the prospective lawbreaker might be receptive. Negotiators recognize these differences in the types of language and the types of wording that might be effective, but all too often, such knowledge resides in the mind of the person who has had experience, who has been trained “on the job” through personal interactions.

We would like to bring this effort into the public eye by doing research on what people think will be effective communications [6]. The objective here is not necessarily to have an encyclopedia of those discussions. We leave that to the professionals. Rather, our objective is to use new research techniques, such as Mind Genomics, to discover the types of mind-sets of prospective lawbreakers and their situations in which things happen. And, for both of them to figure out what type of language might be effective as perceived by a person who’s asked to judge the situation.

The science of criminology has long recognized the existence of mind-sets or types of individuals. It could be no other way. People are different in the reasons underlying their commission of crimes or misdemeanors. We all operate within different life circumstances. Can we make a tool that the negotiator in a crime or the police officer can use for specific circumstances, named at the time of use? The objective would be to use that tool as a way to learn, and to instruct. We do not expect the work to be presented here to be anything other than a start of using Mind Genomics as emergent science to understand the mind of what we might call negotiation [7-10]

The Foundation and Approach of Mind Genomics

The foundation of Mind Genomics is the belief that it is possible to study the reactions to the world of the everyday in a scientific manner. When we look at the specific details of the everyday, we may often find that people react to these details in different ways, but in a limited number of different ways. These different ways are called mind-sets. The objective of Mind Genomics is to understand the world by understanding how people differ from each other in their response to features of and messages about the daily world [11]. Rather than assuming that there are a limited grand number of mind-sets — let’s say three or ten or sixty even — we assume that the mind-set emerges from the pattern of reactions or the pattern of potential reactions to a granular, everyday situation. That is, people can be in one mind-set when they think about how they’re going to order and eat breakfast but be in totally different mind-sets when they realize how they’re going to commute to work. The goal of Mind Genomics, therefore, becomes one to understand these mind-sets at the granular level, doing so in a way which is efficient, inexpensive, educational, reliable, powerful [12-14]. One ultimate goal is to create a “database of everyday life.” This paper presents one application, the messaging or “verbal judo” between a police officer and a prospective lawbreaker.

Setting Up the Mind Genomics Study Through a Templated System

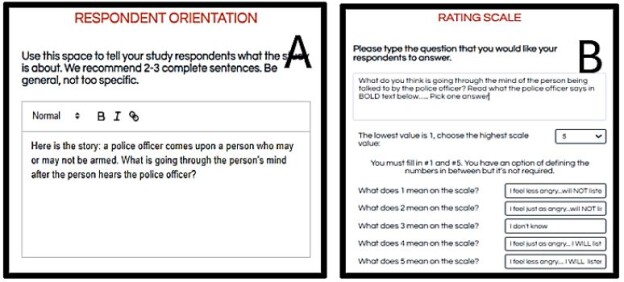

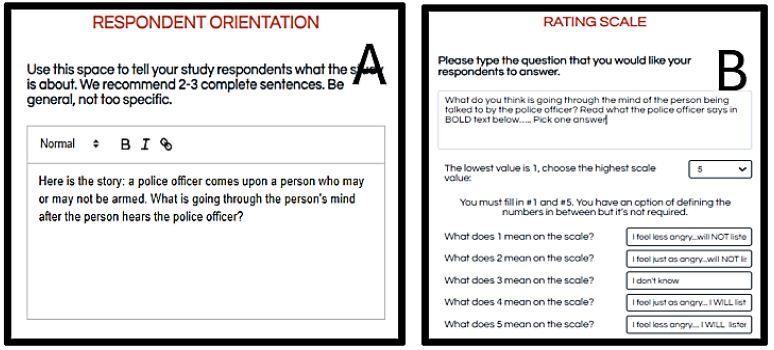

The templated approach developed for Mind Genomics ensures that any user can do a study, whether the user knows the elements to be tested or whether the user wants to be “coached” by AI in the form. of an LLM (large language model) to create these elements. Figure 1, Panel A shows what confronts the user at the start of the study. The user is requested to tell four or select four questions which “tell a story.” Panel A is already filled in but one could imagine Panel A with no questions whatsoever simply with four blanks, one blank per question.

The prospect of course is quite daunting as has been the experience of the authors over the past decades. It is for that reason that we embedded artificial intelligence using ChatGPT 3.5 [15]. ChatGPT 3.5 was programmed to receive a small squib shown in the box on the right (Figure 1, Panel B). The squib describes the issue. From that squib ChatGPT 3.5 creates 15 questions for each iteration [16,17]. The user can iterate again and again, each time creating 15 questions, until the user selects a total of four questions across the various iterations. The user can select the questions, edit them, provide other questions, doing so for many iterations. The Mind Genomics process will record each iteration, whether the elements were selected or not. The result is an education simply through creating questions in each iteration. Thus, the four selected questions could come from a variety of iterations and reflect the results of editing the suggested questions [16,17].

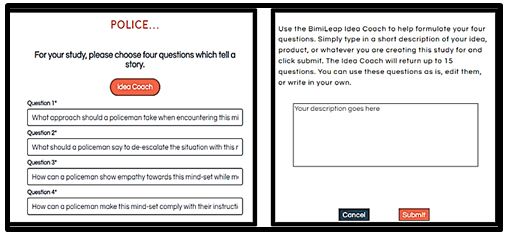

What ends up of course is that the user can drop the questions into the study as shown in Panel A, can edit it, put it into different words, or even use the user’s own ideas (Figure 1, Panel A). Table 1 shows the types of questions which emerge when the user uses Idea Coach ChatGPT for creating the questions.

Table 1: Output of AI for the squib. Topic: A policeman is responding to a situation. What should I ask?

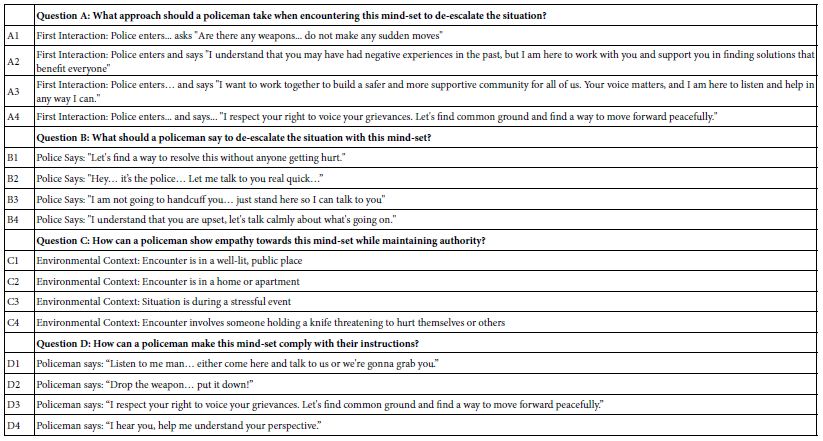

The same approach requiring the user to generate four answers to each question finally selected once again generates a sense of discomfort. The level of discomfort seems to be less, perhaps because it is easier to answer questions than to pose them. Once again AI proves valuable here, reducing the panelist. The user only needs to select Idea Coach and AI is prompted to return with 15 answers to each question. The process can go on several times for each question, resulting in a book of questions and answers to those questions. Table 2 shows the final set of four questions and four answers to each question.

Figure 1: Panel A shows the user interface screen requesting four questions, with the questions filled in. Panel B shows the user interface box to write in the squib for the Idea Coach, using ChatGPT 3.5.

Table 2: The final set of four questions, and the four answers (elements) for each question

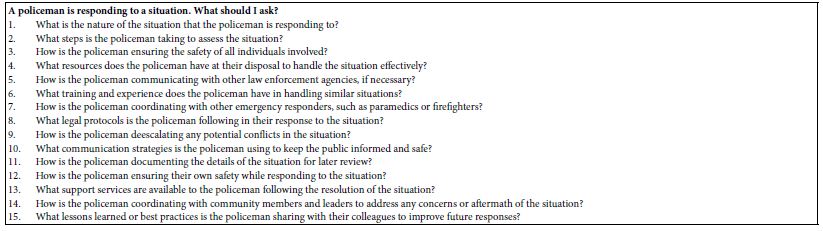

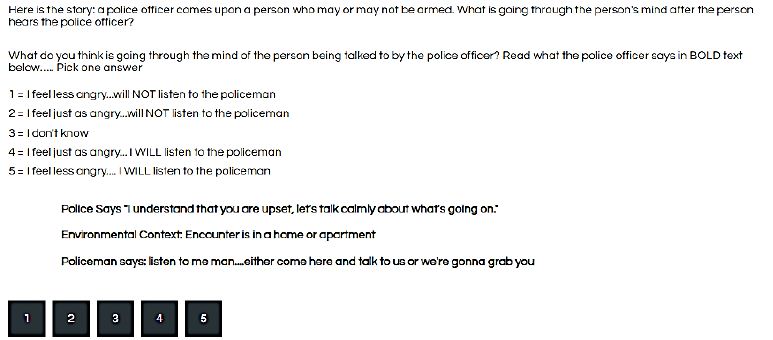

Orienting the Respondents and Providing a Rating Scale

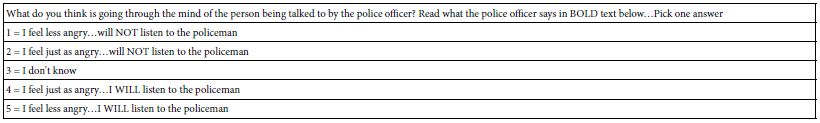

The next step in the setup of the Mind Genomics study involves the creation of the orientation for the respondent and an easy-to-use rating scale. Traditionally, the rating scale has been unidimensional, from low to high, from 1 to 5. More recent efforts have used two-sided rating scales, allowing the respondent to provide two pieces of information in the same scale. It is a two-sided rating scale that we use in this study. The first side involves ratings of listening. The second one involves ratings of reducing anger. Table 3 presents the text of the rating scale. Respondents typically have little problem assigning ratings using this type of scale, even though it would seem that they are making two types of judgments. Figure 2, Panel A shows the screenshot for the respondent orientation provided by the researcher. Figure 2, Panel B shows the set up for the rating scale, allowing the user to select the question itself (top), the number of scale points, and the optional anchoring phrase for each scale point.

Table 3: The rating scale

Figure 2: Panel A shows the user interface to create the respondent orientation. Panel B shows the user interface to create the rating question.

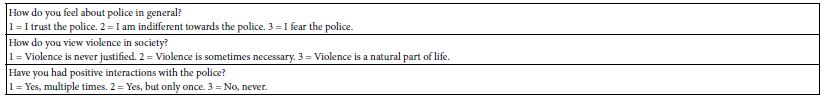

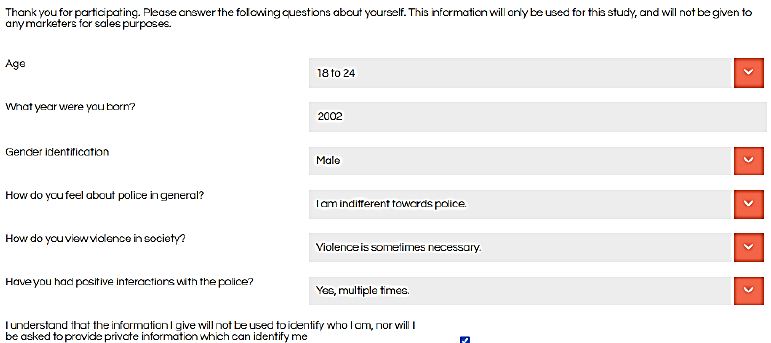

Table 4 shows the three self-profiling questions selected by the user, in addition to two additional standard questions (age, gender). These self-profiling questions allow the user to obtain otherwise impossible-to-obtain information about the respondent. Figure 3 shows the actual pull-down menu as presented to the respondent at the start of the evaluation session.

Table 4: The three self-profiling questions selected by the user

Figure 3: The pull-down menu presenting the self-profiling questions

Once the consumer respondent logs in and completes the self-profiling classification (Figure 3), the respondent is presented with an orientation and immediately evaluates 24 vignettes, one vignette after another (see Figure 4). The vignettes are created by experimental design, a systematized layout. Each respondent evaluates a unique set of the 24 vignettes, the uniqueness guaranteed by a permutation scheme which maintains the mathematical properties of the combinations (statistical independence, equal frequency of appearance, etc.).

Figure 4: Example of a vignette as presented to the respondent, who reads and rates the vignette. The vignette automatically advances to the next vignette after the respondent assigns a rating.

A vignette has two, three, or four elements, at most one element from each question or one answer from each question. According to the experimental design, the combinations of the vignettes are incomplete. That is, the vignettes are not created by the obsessive requirement that each vignette have exactly one element (viz., answer) from each question. That requirement would, in fact, end up being counterproductive in a statistical sense because the 16 elements would not be statistically independent of each other, and only relative value of coefficients would emerge, not the more desirable absolute values.

The strategy of having each respondent evaluate a unique set of combinations was developed by Gofman and Moskowitz in the early 2000’s [18]. The objective was to ensure that Mind Genomics would explore many combinations and thus might be well used as a tool for exploration rather than a tool to confirm what was known. In traditional conjoint measurement, the typical user ends up testing known combinations, creating these limited numbers of combinations to test the hypothesis. It is important in traditional conjoint measurement to “know” the important elements ahead of time. In a complete about face, Mind Genomics was designed to explore the response to messages, elements, welcoming the absence of any ingoing knowledge about “what is important.” In Mind Genomics, the user may have absolutely no idea of what the important elements are, and therefore it makes far more sense to have each person test a unique set of combinations different from the combinations of everybody else. The consequence of that is that the Mind Genomics system is much like an MRI of the mind, looking at different areas, identifying things, and then putting everything together at the end of the experience with one grand computer analysis which shows exactly what every element contributes.

Transformation to Binary Scales and Creation of Equations Using OLS (Ordinary Least Squares) Regression

The analysis of Mind Genomics data follows a simple series of steps and like the setup is templated to make the approach easier for people to use. The rating scale has two dimensions. One dimension is listening, the second dimension is lessening anger. We want to capture both of these. The transformations create two new variables, each taking on the values of 0 or 100, as shown. Each rating thus generates these two binary variables. As a precautionary measure to ensure that every respondent generates some level of variation in these two binary variables, we add a vanishingly small random number (<10-5) to each newly created binary variable. By so doing we ensure that the subsequent analysis using OLS (ordinary least squares) regression will not “crash.”

R54 (Listen to Officer) Ratings 5 and 4 transformed to 100, ratings 1,2, and 3 transformed to 0.

R52 (Lessen Anger) Ratings 5 and 2 transformed to 100, ratings 1, 3 and 4 transformed to 0.

The effort put into creating the combinations now pays out. It is straightforward to apply OLS regression to the data, whether at the level of a single individual or at the level of a group. The equation shows how one deconstructs the rating, or more correctly the transformed binary variable, into the part-worth contribution of each of the 16 elements. The equation does not have an additive constant, meaning that the equation is forced through the origin. This simple expression contains within it all of the information about the driving strength of each of the 16 elements for Listen to Office or for Lessen Anger.

Binary Dependent Variable = k1A1 + k2A2… k16D4

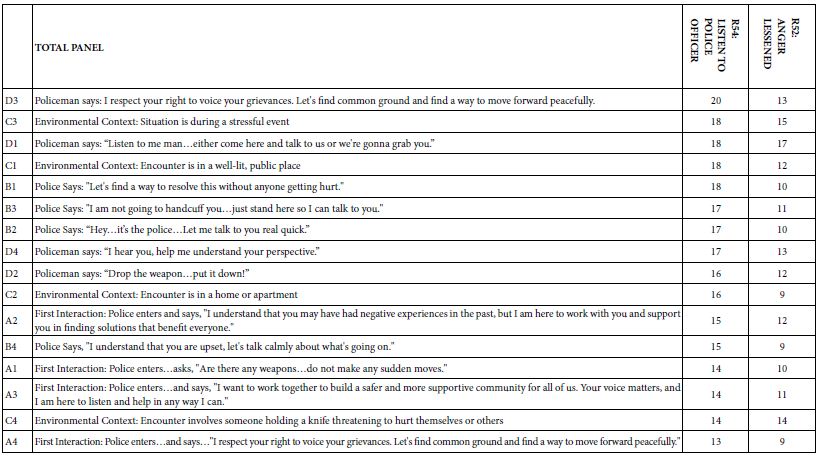

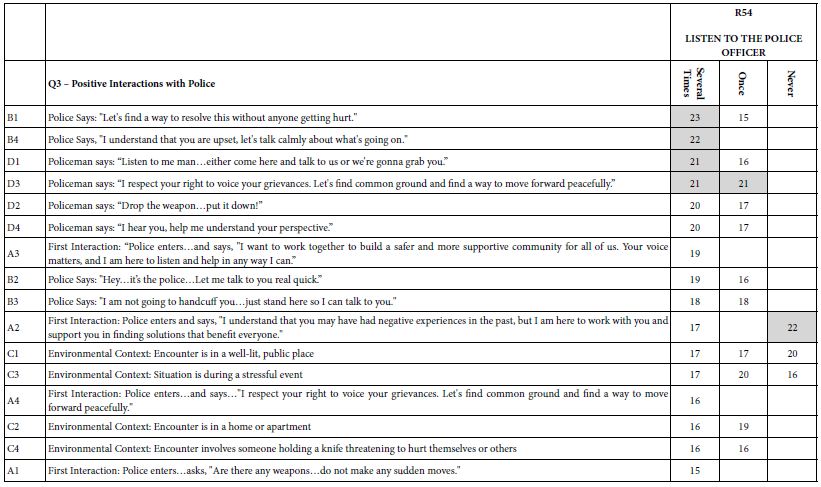

Table 5 shows the coefficients from the ordinary least squares regression. The coefficients are sorted by the magnitude for R54 (Listen to Police Officer). The convention for this analysis will be that any coefficient of 21 or higher will be shaded to highlight as being an extremely important, highly significant coefficient. The value 21 emerges from statistical tests of significance. The second column shows the coefficient for R52 the binary dependent variable for Lessened Anger. In neither case is any element shown as highly significant with a coefficient of 21, although D3 is close: Policeman says I respect your right to voice your grievances.

Table 5: Coefficients for the Total Panel

The fact that there are no very strong elements for R54 (Listen to Police Officer) or for R52 (Lessen Anger) may emerge because people have different criteria, and therefore their ratings may cancel each other out. We can think of two streams meeting another stream in opposite directions. A stream flows quickly, but if two streams meet together and they’re going in opposite directions, often the result is a pool with a lot of disturbance, but the pool is not going fast in any direction. It just becomes a maelstrom. The same thing may occur with the coefficients from the total panel. We may have different groups of people with different ideas, and the question is whether in fact these people are canceling each other out. We will see that when we come to mind-sets, but first we have to work our way through the differences between people as they have defined themselves in the classification questions.

Self-Profiling

The respondents were required to answer three questions at the start of the study, shown in Table 3. Mind Genomics can generate a wall of numbers because of the different binary dependent variables (R54, R52), the 16 elements, and the several groups self-defined by the respondent. To make understanding and discovering patterns easier, we focus from this point forward on one key dependent variable, R54.

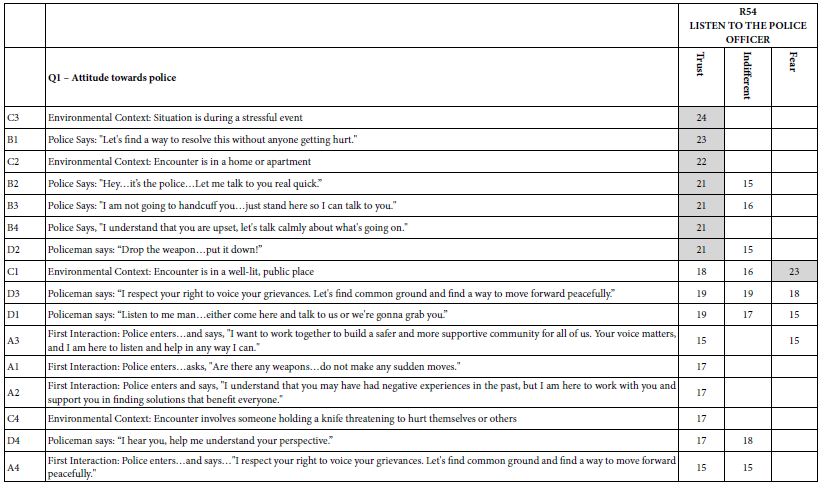

Table 6 shows the coefficients based upon Question 1, attitude towards police. The story in Table 6 is clear. Only one of the three subgroups generate consistently high coefficients, viz., those who say they trust police.

Table 6: Coefficients for elements based on self-profiling Question 1 (Attitude toward police).

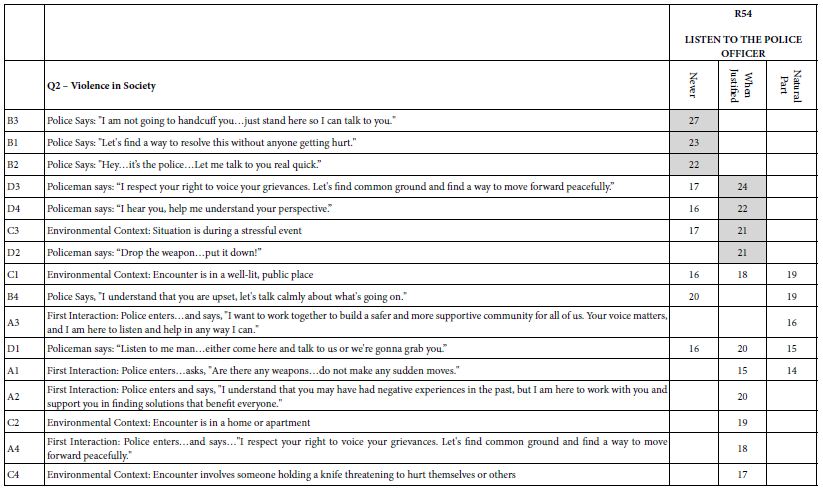

Table 7 shows the coefficients for R54, this time based on how the respondent feels about violence in society. Once again, a story emerges, although not one quite as clear as before. Those who feel that violence is never justified end up saying they will listen to direct statements to them by the police. Those who feel that violence is occasionally warranted say that they will listen in a number of situations, but the common link is not clear. Finally, those who feel that violence is simply part of everyday life do not end up saying that they will listen to the police officer.

Table 7: Coefficients for elements based on self-profiling Question 2 (Violence in society).

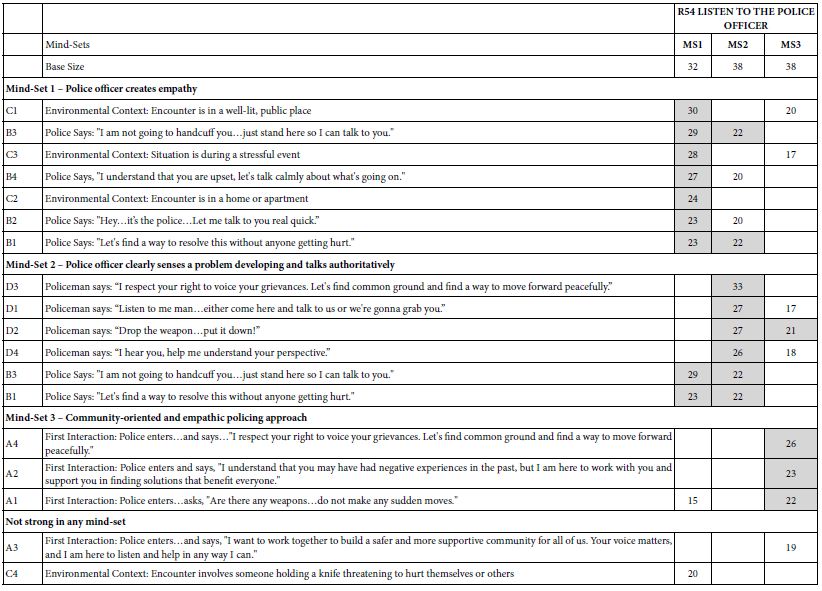

Table 8 shows the coefficients for R54, this time for self-profiling question #3, “positive interactions with police.” Those respondents who say that they have had several positive interactions with the police are likely to listen, especially when spoken to respectfully.

Table 8: Coefficients for elements based on self-profiling Question 3 (Positive interactions with police).

Mind-Sets

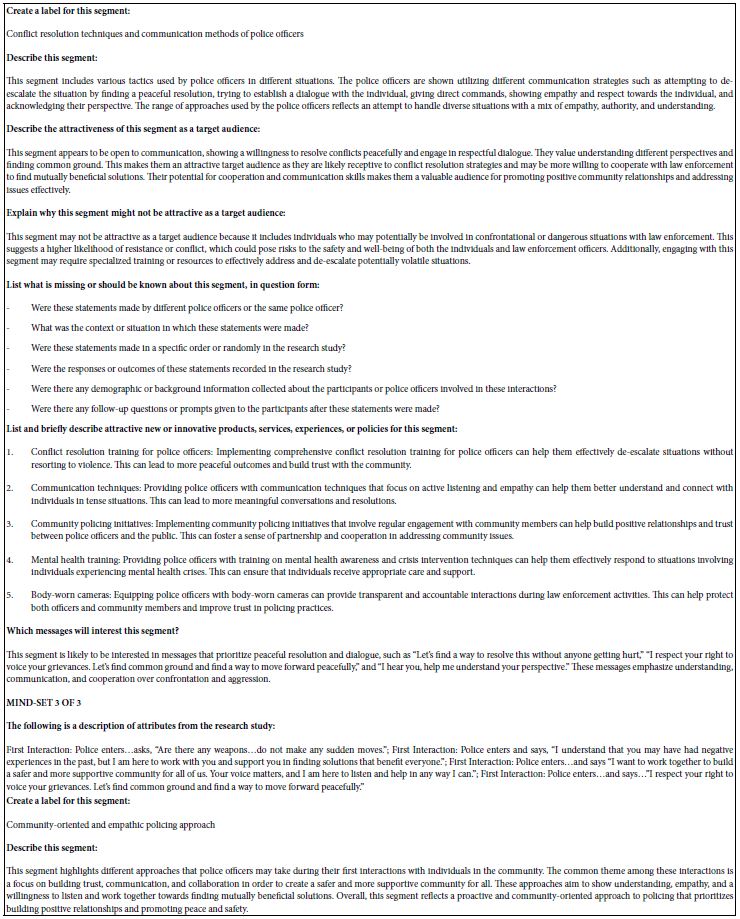

The last analysis creates mind-sets. Mind-sets are defined as clusters of individuals who respond in the same way towards a specific topic. Individuals within a mind-set find certain patterns to be extraordinarily engaging and other patterns to be virtually irrelevant. Mind-sets emerge from statistical analyses of the patterns of coefficients for the individuals. Ideally for a topic such as listening to police officers, the statistical analysis should generate a limited number of clusters of patterns, the mind-sets, with these patterns telling easy to understand “stories.” The former is parsimony, the latter is interpretability.

The creation of mind-sets for these data involved the estimation of 108 individual-level equations, one equation for each respondent. It is just as easy for the computer to create 108 equations as to create one equation, since each respondent’s 24 vignettes were arranged ahead of time to ensure that the 16 elements appeared in a statistically independent fashion. As before, the key dependent variable is R54, Listen to the police officer. The final analysis to generate the mind-sets used k-means clustering [19]. The outcome is two, and then three clusters or mind-sets. The three-mind-set solution was easier to interpret. Table 9 shows the three-mind-set solution, sorted from high to low for each mind-set separately. Elements which generate coefficients of 21 or higher in two mind-sets appear in each mind-set in the proper order, to make interpretation easier. Table 9 shows many more strong performing elements, with these elements telling simpler stories. It is important to keep in mind that these mind-sets emerge without the help of human interpretation except at the very end. All of the analyses come from pure mathematical considerations.

The strong performance of elements in Table 9 should not surprise. The analogy given above for the total panel was of two or more streams, moving swiftly in opposite directions, clashing with each other and creating a pool of turbulent, but non-flowing flowing water. The mind-sets flow in different directions. We see weaker performance for the total panel (see Table 5, column for R54). Only when the different mind-sets emerge do we see how really strong the mind-sets are.

Table 9: The three-mind-set solution emerging from clustering the coefficient on the basis of values for R54 (Listen to the police officer).

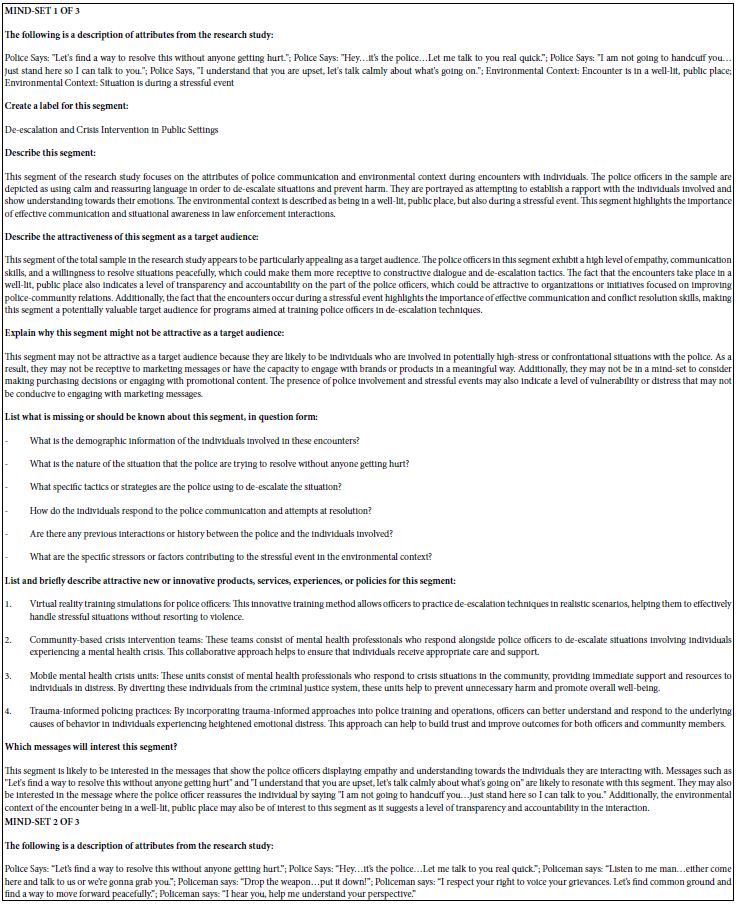

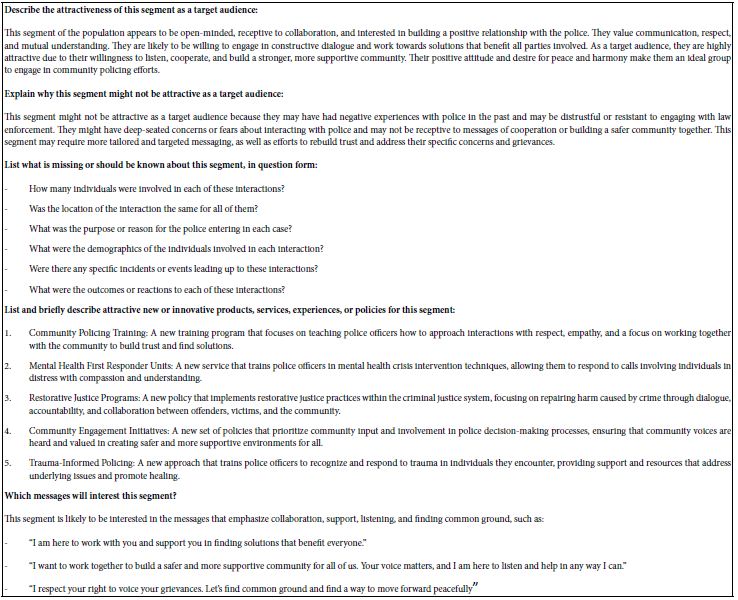

Using AI to Understand the Mind-Sets More Deeply

Our final analysis comprises the deeper interpretation of our mind-sets through artificial intelligence. We know the strong performing elements for the key binary dependent variable R54. Table 9 shows these elements in shade. The LLM embedded in BimiLeap.com, the Mind Genomics platform, “summarizes” the patterns behind these strong performing elements. Table 10 presents these summaries exactly the way they emerged from the LLM. It is important to keep in mind that the user does not have to accept the summarization. For example, the mind-set names used in Table 9 are not those recommended by AI. Rather, the summarization shown in Table 10 is meant as an aid to learning and to critical thinking, essentially acting as a “coach” to suggest other aspects meriting the user’s attention.

Table 10: AI-generated “automated summaries” of strong-performing elements for each of the three mind-sets shown in Table 9.

Discussion and Conclusions

The goal of this study was to demonstrate how a combination of artificial intelligence and Mind Genomics thinking can create different features of the interaction between a potential perpetrator of a violent act and the police. With the increasing power of artificial intelligence as manifested in large language models, it becomes straightforward to request these large language models to provide relevant questions and then for each question relevant answers. We demonstrated this through Idea Coach. Whether or not we created the correct questions and selected the correct answers becomes a minor issue when we realize that we can do an iteration in a minute or less. What would take months of thinking, now with the help of large language models, really takes minutes to do in terms of searching for new questions and in turn for new answers to those questions, the elements of our study.

The first half of the study was devoted to finding the test stimuli. The second half is devoted to finding the response of real people, in our case young males living in the Virginia area. The issue was whether these people would respond in a specific way to the various scenarios, to the different elements combined. The data from our 108 respondents suggest three different mind-sets. It’s important to know that this is our first foray. The first mind-set would be strong responses to listening when the place is familiar and when the police officer says to the effect that “I’m going to not do anything to you, just let’s talk.” The second mind-set stresses that the person says they will listen when there are clear actions that suggest a hostile nature. The police officer clearly senses a situation and the problem developing and talks authoritatively. It’s important to note that the police officer who talks authoritatively may also want to talk in a more peaceful manner to find common ground. The third mind-set is that the police officer really knows what’s going to happen and essentially threatens or orders the potential perpetrator not to do anything. As a closing comment, one should keep in mind that these mind-sets are not hard and fast divisions, but interpretable regions on a continuum. That itself is key learning, that sometimes there are strong differences, opposite or independent, orthogonal, and sometimes the mindsets fall along a continuum of power. It’s quite possible that in the case of police behavior in these situations we are dealing with positions on a continuum rather than radically different mind-sets. Only experimentation will tell us.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Vanessa Marie B. Arcenas for helping to produce this manuscript.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ChatGPT | Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| OLS regression | Ordinary Least Squares regression |

Competing Interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Anshel MH (2000) A conceptual model and implications for coping with stressful events in police work. Criminal justice and Behavior 27(3): 375-400.

- Bazemore G, and Senjo S (1997) Police encounters with juveniles revisited: An exploratory study of themes and styles in community policing. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 20(1): 60-82.

- Hulderman MA (2003) Decision-making styles and learning strategies of police officers: Implications for community policing. Oklahoma State University.

- Ramshaw P (2012) On the beat: Variations in the patrolling styles of the police officer. Journal of Organizational Ethnography 1(2): 213-233.

- Wachi T, Watanabe K, Yokota K, Otsuka Y, and Lamb ME (2016) The relationship between police officers’ personalities and interviewing styles. Personality and Individual Differences 97: 151-156.

- Mendoza C, Mendoza C, Deitel Y, Rappaport S, Moskowitz HR (2023) Empowering young people to become Researchers: What does it take to become a police officer? Psychology Journal Research Open 5: 1-12.

- Cooper HHA (2005) Close Encounters of an Unpleasant Kind: Preliminary Thoughts on the Stockholm Syndrome. Journal of Police Crisis Negotiations 5(2): 81-109.

- Donohue WA, and Roberto AJ (1993) Relational development as negotiated order in hostage negotiation. Human Communication Research 20(2): 175-198.

- Greenstone JL (2013) The elements of police hostage and crisis negotiations: Critical incidents and how to respond to them. Routledge.

- Soskis DA, and Van Zandt CR (1986) Hostage negotiation: Law enforcement’s most effective nonlethal weapon. Behavioral Sciences & the Law 4(4): 423-435.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A (2007) Selling Blue Elephants: How to Make Great Products that People Want Before They Even Know They Want Them. Pearson Education.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J and Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind genomics. Journal of sensory studies 21(3): 266-307.

- Porretta S, Gere A, Radványi D and Moskowitz H (2019) Mind Genomics (Conjoint Analysis): The new concept research in the analysis of consumer behaviour and choice. Trends in food science & technology 84: 29-33.

- Radványi D, Gere A and Moskowitz HR (2020) The mind of sustainability: a mind genomics cartography. International Journal of R&D Innovation Strategy (IJRDIS): 2(1): 22-43.

- Wu T, He S, Liu J, Sun S, et al (2023) A brief overview of ChatGPT: The history, status quo and potential future development. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 10(5): 1122-1136.

- Mendoza C, Mendoza C, Rappaport S, Deitel J, Moskowitz HR (2023) (c) Empowering young researchers to think critically: Exploring reactions to the ‘Inspirational Charge to the Newly-Minted Physician’. Psychology Journal, Research Open 2: 1-9.

- Mendoza C, Mendoza C, Rappaport S, Deitel Y, Moskowitz H (2023) Empowering Young Students to Become Researchers: Thinking of Today’s Gasoline Prices. Mind Genom Stud Psychol Exp 2(2): 1-14.

- Gofman A, Moskowitz H (2010) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127-145.

- Likas A, Vlassis N, Verbeek JJ (2003) The global k-means clustering algorithm. Pattern Recognition 36: 451-461.

Fertility Preservation Among Cancer Patients in Saudi Arabia: A Hot Topic

DOI: 10.31038/CST.2024923

Abstract

The future quality of life of cancer patients with respect to their fertility is impacted by cancer treatment for those who were diagnosed before or during their reproductive years. Fertility cryopreservation technologies give hope to cancer survivors for life following cancer treatments. However, a limited number of patients are taking advantage of the benefits provided by fertility preservation alternatives because of a lack of standardized guidelines, a lack of awareness, and the need for additional education and training.

Keywords

Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices, Fertility preservation, Cancer patients, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Worldwide, the prevalence of cancer patients is increasing, with a long-term incidence projection showing that there will be a 1.8-fold increase by 2030, making it a life-threatening diagnosis [1]. Fortunately, recent advances in cancer treatment have resulted, for example, in female cancer survival rates increasing to 10% of all survivors under the age of 40 [2,3]. However, it is known that a number of cancer treatments harm the reproductive system, resulting in sterility or infertility. In order to improve the quality of life of cancer survivors of childbearing age, fertility preservation (FP), advice, and treatment are increasingly being offered [4]. The knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) regarding FP, especially in cancer patients, are very advanced worldwide. In Saudi Arabia, FP in cancer patients is a topic that has gained increasing attention and importance. However, it is still a difficult problem, and for a variety of reasons, referral and consulting are not yet widely used.

The KAP among Oncologist

According to our previous studies in 2011, we identified several knowledge gaps among oncologists that could impact their attitude, which in turn was reflected in their poor practice. For example, the possibility of preserving female fertility was unknown to 45% of oncologists [5]. At that time, there was limited awareness about FP options, a lack of standardized guidelines, and a need for further education and training in this area, especially in the absence of legislation.

Twelve years after the above-mentioned study, the advice of senior religious scientists in 2018 allowed the freezing of tissue of the ovarian membrane, the entire ovary, and eggs for later use in reproduction in order to preserve the offspring. In a recent study conducted in 2023, we investigated whether oncologists’ knowledge, attitudes, and referral procedures regarding FP have improved. Their level of understanding has greatly increased, as we have discovered. Doctors were actually found to be significantly more knowledgeable about a wide range of female FP options, the most prevalent of which was egg cryopreservation (77%), than other options. It was still necessary to improve patient counseling and referrals to fertility services, though. Our results demonstrate Saudi Arabia’s deficiency in clinical practice standards for FP in cancer patients. [6].

The KAP among Health Practitioners

Understanding the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of health practitioners toward fertility preservation is crucial in ensuring that individuals receive accurate information and appropriate care regarding their reproductive options.

A recent study conducted in Saudi Arabia aimed to assess the attitude of health practitioners towards fertility preservation and showed that clinical practitioners’ knowledge is still inadequate. They concluded that there is a need to train health practitioners and establish practice guidelines and fertility preservation clinics for cancer patients [7].

The KAP among Medical Student

Medical students are the future doctors, and in order to successfully deal with the topic of FP, medical training should begin. To implement cancer education curricula related to fertility preservation, it is necessary to identify any gaps and other barriers that could be overcome through medical education to improve future clinical practices. Our recent study on the attitude and knowledge among Saudi medical students toward FP showed respectable awareness and attitudes toward FP. However, there are still some gaps; almost half of the respondents mentioned that cancer treatment should be started before FP, suggesting the need to improve education about FP in the medical curriculum [8].

The Knowledge among Cancer Patients

Cancer patients who may face fertility challenges in the future were recently surveyed. The study by Abusanad A. et al. in 2022 showed that 56.30% of the cancer patients surveyed had satisfactory knowledge about the consequences of cancer treatment for infertility and expressed a desire to have children through FP in the future. However, this desire has been hampered by limited oncofertility care and FP procedures. Unfortunately, such patients were occasionally referred to a specific fertility facility, where only 17% saw a fertility specialist and only 37.8% received fertility counseling [4].

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, there have not been studies addressing such an important topic in our region for a decade. To meet the patient’s needs and improve the quality of life of cancer survivors, the best way is to increase cancer awareness through cancer education and disseminate information about cancer prevention. This can be done in a number of ways: through educational events and continuing medical education programs for medical students, oncologists, and nurses caring for cancer patients whose fertility is affected by cancer treatment. Such educational programs will expand their knowledge and improve their practice. The public should be aware of the availability of fertility preservation services in government and private centers, as well as the cost, timing, and various procedures.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, for funding through the Vice Deanship of Scientific Research Chairs.

Conflict of Interest

The author has no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Arafa MA, Rabah DM, Farhat K (2020) Rising cancer rates in the Arab World: now is the time for action. East Mediterr Health J. 26(6): 1-5 [crossref].

- McLaren JF, Bates GW (2012) Fertility preservation in women of reproductive age with cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Dec; 207(6): 455-62 [crossref].

- Dursun P, Doğan NU, Ayhan A (2014) Oncofertility for gynecologic and non-gynecologic cancers: fertility sparing in young women of reproductive age. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. Dec; 92(3): 258-67 [crossref].

- Abusanad A, Mokhtar AMA, Aljehani SAA, Aljuhani KFA, Saleh KAA, Alsubhi BH, et al. (2022) Oncofertility care and influencing factors among cancer patients of reproductive age from Saudi Arabia. Front Reprod Health. Nov 17; 4: 1014868. [crossref]

- Arafa MA, Rabah DM (2011) Attitudes and practices of oncologists toward fertility preservation. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 33: 203-7. [crossref]

- Arafa MA, Abdulkader SM, Farhat KH, Rabah DM, Awartani DK, Aldriweesh AA, et al. (2023) Are There Any Developments in the Attitudes and Practices of Oncologists Regarding Fertility Preservation in Saudi Arabia After 12 Years? Cureus. Sep 2; 15(9): e44562. [crossref]

- Ahmad Sindi R, Salem Bagabas M, Mamdoh Al-Manabre L, Zahi Al-Sofee R, Yousef Rednah R, Meshal Al-Jahdali S (2022) Evaluation of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Health Practitioners towards Fertility Preservation in Cancer Patients in an Environmental Region of Saudi Arabia. J Environ Public Health. Jun 6; 2022: 6404837. [crossref]

- Karim Hamda Farhat, Mostafa Ahmed Arafa, Danny Munther Rabah, Deana Khalid Awartani, Shahad Hussein Bajunaid, Seham Majid Abdulkader, et al. (2023) Fertility Preservation among Cancer Patients in Saudi Arabia: Knowledge and Attitudes of Medical Students. Dubai Med J 6 (Suppl. 1): 5-10.

Thermal Properties of Natural and Hybrid Fiber Reinforced Composites

Abstract

The thermal stability of natural fiber composites is a relevant aspect to be considered since the processing temperature plays a critical role in the manufacturing process of composites. At higher temperatures, the natural fiber components (cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin) start to degrade and their major properties (mechanical and thermal) change. Different methods are used in the literature to determine the thermal properties of natural fiber composites as well as to help to understand and determine their suitability for a certain applications (e.g., Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and differential mechanical thermal analysis (DMA)). Weight loss percentage, the degradation temperature, glass transition temperature (Tg), and viscoelastic properties (storage modulus, loss modulus, and the damping factor) are the most common thermal properties determined by these methods. This paper provides an overview of the recent advances made regarding the thermal properties of natural and hybrid fiber composites in thermoset and thermoplastic polymeric matrices. First, the main factors that affect the thermal properties of natural and hybrid fiber composites (fiber and matrix type, the presence of fillers, fiber content and orientation, the treatment of the fibers, and manufacturing process) are briefly presented. Further, the methods used to determine the thermal properties of natural and hybrid composites are discussed. It is concluded that thermal analysis can provide useful information for the development of new materials and the optimization of the selection process of these materials for new applications. It is crucial to ensure that the natural fibers used in the composites can withstand the heat required during the fabrication process and retain their characteristics in service.

Keywords

Natural fiber reinforced composite material, Thermal analysis, Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), Differential mechanical thermal analysis (DMA)

Introduction

The application of composites has continuously increased across many industries, in particular in the automotive and aerospace industries where lower weight and high resistance are key factors. The most commonly used fibers that attend these requirements are carbon and glass fibers [1-3]. However, nowadays, the industry is seeking new desirable characteristics of composite materials, such as renewability, eco-friendliness, and low cost. Consequently, there has been great interest in research and innovation in natural fiber composites owing to the advantages of these materials compared to their synthetic fiber counterparts (i.e., lower environmental impact and lower cost), supporting their potential across a wide range of applications in several industrial sectors [4-9]. The natural fiber-reinforced composites (NFRCs) are used mainly in non-structural car body parts, such as door panels, package trays, hat racks, instrument panels, internal engine covers, sun visors, boot liners, oil air filters, and even progressing to more structurally demanding parts, such as seat backs and exterior underfloor paneling [10,11]. Nowadays, most of the automotive makers, such as Audi, Volkswagen, Toyota, Daimler-Benz, Volvo, Ford, etc., use NFRCs to produce components. The continually growing demands for lightweight and fuel-efficient vehicles will further push the growth of NFRCs in the automotive market. There are other exciting market trends going forward in many different industries. For example, tri-dimensional hybrid natural fiber reinforcement preforms have been used recently by sports car manufacturers, such as Porsche and even McLaren in Formula 1 .Other applications of NFRCs include sport equipment, musical instruments, aerospace, construction industry [12-14], and ballistic armour [15,16].

Several types of natural fibers are currently used in industry, such as jute, sisal, oil palm, kenaf, and flax, which are well established in the global market with a well-defined production line. However, new promising natural fibers are being discovered and used on a smaller scale or are still being used only for research. This is the case of the buriti and curauáfibers, for example, that still need some improvements in their production line to be more commercially affordable and reach widespread use [17,18]. They are used as reinforcement fibers in thermoset or thermoplastic polymeric matrix in a variety of applications [19]. Depending upon the matrix type, NFRCs are categorized into completely biodegradable or partially biodegradable composites.The growing importance of natural fiber reinforced composites is reflected by the increasing number of publications (e.g., reviews, patents, book chapters, and books) during the recent years [20-25]. Therefore, it is important to study their thermal and mechanical behaviour in order to utilize their full potential. The thermal stability of natural fiber composites is a relevant aspect to be considered as the processing temperature plays a crucial role in the fabrication process of the composites. At higher temperatures, the natural fiber components (i.e., cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin), start to degrade and the major properties (mechanical and thermal) of the composite change. Intense research efforts are continuously made and some of the shortcomings of NFRCs were addressed by recent advancements in fiber treatment and modification, exploration of new natural fibers, and hybridization. The fiber modification techniques provide improved fiber–matrix interfacial adhesion, improved fiber roughness, and wettability and depend on the particular fiber/matrix used and the composite application, while the hybridization methods provide flexibility in fiber selection for the material properties according to the end-use application requirements.

Even though there are many recent review articles concerning the use of natural fibers in the production of natural hybrid composites [26-34], one topic that was not covered in any significant detail relates to the thermal characterisation of NFRCs. This paper provides an overview of the recent advances in the thermal properties of natural and hybrid natural fiber composites in thermoset and thermoplastic polymeric matrices. First, the main factors that affect the thermal properties of natural and hybrid fiber composite materials (fiber and matrix type, the presence of additive fillers, fiber content and orientation, the treatment of the fibers, manufacturing process, and type of loading) are briefly presented. Further, the methods used to determine the thermal properties of natural and hybrid composites are discussed. Finally, some conclusions and critical challenges and future perspectives and research activities are summarized.

Influencing Factors

The main factors that affect the thermal properties of natural and hybrid fiber compo-site materials are: fiber and matrix type, the presence of additive fillers, fiber content and orientation, the treatment of the fibers, manufacturing process, and type of loading [35].

Methods Used to Determine the Thermal Properties of Natural and Hybrid Composites

The following methods are used

a) Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

b) Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

c) Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

Conclusions

Thermal analysis can provide useful information for the development of new materials and optimization of the selection process of these materials for new applications. The most common thermal properties studied in the literature are: the percentage of weight loss, the degradation temperature, Tg, and viscoelastic properties (storage modulus, loss modulus, and the damping factor). Different factors affect the thermal properties of natural fiber composites (i.e., fiber and matrix type, the presence of fillers, fiber content, and fiber orientation, the chemical treatment of the fibers, manufacturing process, and type of loading). It is crucial to ensure that the natural fibers used in the composites can withstand the heat required during the fabrication process and retain their characteristics after exposure to heat. Different approaches were used in the literature for the enhancement of thermal properties of natural fiber-based composite materials. For example, using natural fibers with low lignin content leads to a better thermal performance of composites. Another approach involves the removal of lignin through fiber treatment. Finally, the incorporation of synthetic fillers or synthetic fibers in natural fiber reinforced composites increase their thermal stability.

References

- Guo R, Xian G, Li C, Huang X, Xin M (2021) Effect of fiber hybridization types on the mechanical properties of carbon/glass fiber reinforced polymer composite rod. Mech Adv Mater Struct 1-13.

- Li C, Xian G, Li H (2019) Tension-tension fatigue performance of a large-diameter pultruded carbon/glass hybrid rod. Int J Fatigue 120: 141-149.

- Lal HM, Uthaman A, Li C, Xian G, Thomas S (2022) Combined effects of cyclic/sustained bending loading and water immersion on the interface shear strength of carbon/glass fiber reinforced polymer hybrid rods for bridge cable. Constr Build Mater 314: 125587.

- Budhe S, de Barros S, Banea MD (2019) Theoretical assessment of the elastic modulus of natural fiber-based intra-ply hybrid composites. J Braz Soc Mech Sci Eng 41: 263.

- Banea MD, Neto JSS, Cavalcanti DKK (2021) Recent Trends in Surface Modification of Natural Fibres for Their Use in Green Composites. Springer 329-350.

- Wambua P, Ivens J, Verpoest I (2003) Natural fibres: Can they replace glass in fibre reinforced plastics? Compos Sci Technol 63: 1259-1264.

- De Queiroz HFM, Banea MD, Cavalcanti DKK (2021) Adhesively bonded joints of jute, glass and hybrid jute/glass fibre-reinforced polymer composites for automotive industry. Appl Adhes Sci 9: 2.

- De Queiroz HFM, Banea MD, Cavalcanti DKK (2020) Experimental analysis of adhesively bonded joints in synthetic- and natural fibre-reinforced polymer composites. J Compos Mater 54: 1245-1255.

- De Queiroz HFM, Banea MD, Cavalcanti DKK, de Souza e Silva Neto J (2021) The effect of multiscale hybridization on the mechanical properties of natural fiber-reinforced composites. J Appl Polym Sci 138: 51213.

- Pickering KL, Efendy MA Le TM (2016) A review of recent developments in natural fibre composites and their mechanical performance. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 83: 98-112.

- Marichelvam MK, Manimaran P, Verma A, Sanjay MR, Siengchin S, et al. (2021) A novel palm sheath and sugarcane bagasse fiber based hybrid composites for automotive applications: An experimental approach. Polym Compos 42: 512–521.

- Akampumuza O, Wambua PM, Ahmed A, Li W, Qin XH (2017) Review of the applications of biocomposites in the automotive industry. Polym Compos 38: 2553-2569.

- Fitzgerald A, Proud W, Kandemir A, Murphy RJ, Jesson DA, et al. (2021) A Life Cycle Engineering Perspective on Biocomposites as a Solution for a Sustainable Recovery. Sustainability 13: 1160.

- Islam MS, Ahmed SJU (2018) Influence of jute fiber on concrete properties. Constr Build Mater 189: 768-776.

- Benzait Z. Trabzon L (2018) A review of recent research on materials used in polymer–matrix composites for body armor application. J Compos Mater 52: 3241-3263.

- Braga FDO, Bolzan LT, da Luz FS, Lopes PHLM, Lima ÉP, et al. (2017) High energy ballistic and fracture comparison between multilayeredarmor systems using non-woven curaua fabric composites and aramid laminates. J Mater Res Technol 6: 417-422.

- Sanjay M, Siengchin S, Parameswaranpillai J, Jawaid M, Pruncu CI, et al. (2019) A comprehensive review of techniques for natural fibers as reinforcement in composites: Preparation, processing and characterization. Carbohydr Polym 207: 108-121.

- Silva RV, Aquino EMF (2008) CurauaFiber: A New Alternative to Polymeric Composites. J Reinf Plast Compos 27: 103-112.

- Cavalcanti DKK, Banea MD, Neto JSS, Lima RAA (2021) Comparative analysis of the mechanical and thermal properties of polyester and epoxy natural fibre-reinforced hybrid composites. J Compos Mater 55: 1683-1692.

- Chaudhary V, Bajpai PK, Maheshwari S (2020) Effect of moisture absorption on the mechanical performance of natural fiber reinforced woven hybrid bio-composites. J Nat Fibers 17: 84-100.

- Maslinda AB, Abdul Majid MS, Ridzuan MJM, Afendi M, Gibson AG (2017) Effect of water absorption on the mechanical properties of hybrid interwoven cellulosic-cellulosic fibre reinforced epoxy composites. Compos Struct 167: 227-237.

- Choudhury MR, Debnath K (2021) Green Composites: Introductory Overview. Springer1-20.

- El Messiry M (2021) Green Composite as an Adequate Material for Automotive Applications. Springer 151-208.

- Mahmud S, Hasan KMF, Jahid MA, Mohiuddin K, Zhang R, et al. (2021) Comprehensive review on plant fiber-reinforced polymeric biocomposites. J Mater Sci 56: 7231-7264.

- Do Nascimento HM, dos Santos A, Duarte VA, Bittencourt PRS, Radovanovic E, et al. (2021) Characterization of natural cellulosic fibers from Yucca aloifolia L. leaf as potential reinforcement of polymer composites. Cellulose 28: 5477-5492.

- Gurunathan T, Mohanty S, Nayak SK (2015) A review of the recent developments in biocomposites based on natural fibres and their application perspectives. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 77: 1-25.

- Mehdikhani M, Gorbatikh L, Verpoest I, Lomov SV (2018) Voids in fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review on their formation, characteristics, and effects on mechanical performance. J Compos Mater 53: 1579-1669.

- Sanjay MR, Madhu P, Jawaid M, Senthamaraikannan P, Senthil S. et al. (2018) Characterization and properties of natural fiber polymer composites: A comprehensive review. J Clean Prod 172: 566-581.

- Siakeng R, Jawaid M, Ariffin H, Sapuan SM, Asim M, et al. (2019) Natural fiber reinforced polylactic acid composites: A review. Polym Compos 40: 446-463.

- ThyavihalliGirijappa YG, MavinkereRangappa S, Parameswaranpillai J, Siengchin S (2019) Natural Fibers as Sustainable and Renewable Resource for Development of Eco-Friendly Composites: A Comprehensive Review. Front Mater 6: 226.

- Sivaranjana P, Arumugaprabu V (2021) A brief review on mechanical and thermal properties of banana fiber based hybrid composites. SN Appl Sci 3: 176.

- Swolfs Y, Gorbatikh L, Verpoest I (2014) Fibre hybridisation in polymer composites: A review. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 67: 181-200.

- Mahmoud Zaghloul MY, YousryZaghloul MM, YousryZaghloul MM (2021) Developments in polyester composite materials–An in-depth review on natural fibres and nano fillers. Compos Struct 278: 114698.

- Odesanya KO, Ahmad R, Jawaid M, Bingol S, Adebayo GO, et al. (2021) Natural Fibre-Reinforced Composite for Ballistic Applications: A Review. J Polym Environ 29: 3795–3812.

- Neto JSS, de Queiroz HFM, Aguiar RAA, Banea M (2021) Polymers 13: 4425.

Integrative Journal of Nursing and Medicine

Integrative Journal of Nursing and Medicine

Archives of Women Health and Care

Archives of Women Health and Care

Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism Journal

Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism Journal

Integrative Gynecology and Obstetrics Journal

Integrative Gynecology and Obstetrics Journal

Cancer Studies And Therapeutics

Cancer Studies And Therapeutics

A Narrative Enquiry on the Ethno-Religious Conflict on the Health of Women in Plateau, Nigeria

Abstract

This study investigates the impact of ethno-religious conflict on the health of women in Plateau State, Nigeria, utilizing a comprehensive review of existing documents and literature. Plateau State, often referred to as the “Home of Peace and Tourism,” has been plagued by persistent ethno-religious violence, which has had profound implications for the health and well-being of its female population. This research synthesizes data from governmental reports, non-governmental organisation (NGO) publications, academic journals, and health surveys to delineate the multifaceted health challenges faced by women in this region. The findings reveal that ethno-religious conflicts in Plateau State have significantly exacerbated physical, mental, and reproductive health issues among women. The physical health impacts include increased rates of injuries, malnutrition, and infectious diseases due to disrupted living conditions and healthcare services. Psychologically, women experience heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a result of exposure to violence, displacement, and the loss of family members. Furthermore, reproductive health is severely affected, with limited access to prenatal and postnatal care, higher instances of sexual violence, and inadequate menstrual health management. The study implicated policymakers, health care providers, humanitarian organisations, faith-based organisation working in Plateau State. Recommendations are discussed.

Keywords

Religion, Ethnicity, Health, Women, Plateau, Nigeria

Introduction

Ethno-religious conflicts have long been a persistent challenge in various parts of Nigeria, significantly impacting the social fabric and overall well-being of its population. Plateau State, located in the central region of Nigeria, is one of the areas most affected by these conflicts. The intersection of ethnic diversity and religious plurality in Plateau has often led to violent clashes between different groups, resulting in substantial socio-economic and health-related repercussions. The health of women, in particular, has been severely affected by these conflicts. Women in conflict zones often face unique vulnerabilities, including displacement, loss of livelihoods, and increased exposure to violence and exploitation. These factors collectively exacerbate health issues ranging from physical injuries and psychological trauma to disruptions in maternal and child healthcare services [1,2].

In Plateau State, the cyclical nature of ethno-religious violence has created a volatile environment where healthcare delivery is consistently disrupted. Hospitals and clinics are often targets during conflicts, leading to their destruction or abandonment, which severely limits access to essential medical services for women. Additionally, the breakdown of social networks and support systems further compounds the health challenges faced by women, as they are often left to cope with the aftermath of violence with limited resources and support [3].

Studies have shown that women in conflict-affected areas of Plateau State experience higher rates of physical and mental health issues compared to those in more stable regions. For instance, maternal mortality rates are significantly higher in these areas due to the lack of access to emergency obstetric care and skilled birth attendants. Furthermore, the pervasive fear and stress associated with ongoing conflict contribute to a higher prevalence of mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety, among women [4,5].

This study aims to explore the multifaceted impact of ethno-religious conflict on the health of women in Plateau State, Nigeria, and to identify potential strategies for mitigating these effects. By examining the direct and indirect health consequences of conflict and highlighting the experiences of affected women, this research seeks to contribute to a better understanding of the challenges and inform policy and programmatic responses to support women’s health in conflict-affected regions.

Research Methodology

This study is a qualitative study using narrative method. The narrative method is a qualitative research approach that focuses on the collection, analysis, and interpretation of stories to understand the experiences, meanings, and cultural contexts of individuals or groups. Data was gotten from gazettes, periodicals, journal articles and archives of humanitarian organization such as governmental organizations, non-governmental organisations, civil based organizations, community based organization and faith-based organization. The data was analyzed using discourse analysis.

Ethno-Religious Conflict in Plateau, Nigeria

Plateau State, located in central Nigeria, has been a hotspot for ethno-religious conflicts for several decades. This region, known for its ethnic and religious diversity, has witnessed recurrent violent clashes between different groups, primarily driven by competition over land, political power, and resources. These conflicts are often framed along ethnic and religious lines, exacerbating tensions and leading to significant loss of life, displacement, and destruction of property. The roots of ethno-religious conflicts in Plateau State can be traced back to colonial and post-colonial policies that disrupted traditional land ownership and governance structures. The British colonial administration’s divide-and-rule tactics, coupled with the post-independence government’s failure to address these divisions, laid the groundwork for contemporary conflicts [6].

Plateau State is home to over 50 ethnic groups, with the Berom, Afizere, and Anaguta being the indigenous ethnicities, while the Hausa-Fulani are significant settler communities. The state is also religiously diverse, with a roughly equal distribution of Christians and Muslims. This diversity, while a potential strength has often been exploited by political actors to mobilize support and resources, deepening ethnic and religious divides. Several factors contribute to the ethno-religious conflicts in Plateau State. First, the competition for fertile land and grazing rights between indigenous farming communities and migrant herders is a primary driver of conflict. This competition has intensified with population growth and environmental changes, leading to frequent clashes. Second, the political marginalization of certain ethnic groups fuels resentment and conflict. Indigenous groups often feel that the settler communities, particularly the Hausa-Fulani, are favored in political appointments and economic opportunities. Third, religious identity is a significant factor in Plateau’s conflicts. Incidents of religious violence elsewhere in Nigeria often spill over into Plateau State, inflaming local tensions. Both Christians and Muslims perceive themselves as victims of marginalization and discrimination, leading to mutual suspicion and hostility. Fourth, high levels of youth unemployment and poverty create a fertile ground for recruitment into militant groups. Young people, feeling disenfranchised and without prospects, are easily mobilized by leaders who exploit ethnic and religious narratives for their purposes [7-11].

The impacts of the conflicts in Plateau State cannot be underestimated. First, there is the loss of life and property. Thousands have been killed in violent clashes, and many more have been injured or displaced. Entire communities have been destroyed, with homes, schools, and places of worship burnt down [3]. Second, the conflicts have led to massive internal displacement, with many people living in camps under harsh conditions. Displacement disrupts education, healthcare, and economic activities, perpetuating poverty and instability. Third, the continuous cycle of violence has caused deep psychological trauma among the affected populations, particularly women and children. This trauma manifests in increased mental health issues and social fragmentation. Fourth, the persistent conflicts have severely affected the local economy. Agriculture, the mainstay of the state’s economy, has been disrupted, leading to food insecurity and economic decline [12-14].

Various efforts have been made to address the conflicts in Plateau State but the issue has continued to escalate with women being at the receiving end. The first effort of the government is the deployment of security agencies. The Nigerian government has deployed security forces to quell violence and established commissions of inquiry to investigate the causes of conflicts. However, these measures have often been criticized for being reactive rather than preventive [15]. Another intervention of the government was the setting the pace for dialogue and reconciliation initiatives. Local and international organizations have initiated dialogue and reconciliation programs aimed at fostering understanding and cooperation between conflicting groups. These initiatives include peace education, interfaith dialogues, and community mediation [7]. Also, there are the economic empowerment programs such as vocational training and economic empowerment programs targeting youth. These programs aim to reduce unemployment and provide alternative livelihoods. Unfortunately, these strategies have not yielded the needed results because the ethno-religious conflicts in Plateau State are complex and multifaceted, rooted in historical grievances, competition for resources, political marginalization, and religious tensions [16].

Women and Conflict in Nigeria

Women in Nigeria are significantly affected by various forms of conflict, including ethno-religious violence, insurgency, communal clashes, and political unrest. These conflicts, which are prevalent in different regions of the country, have profound and multifaceted impacts on women’s lives. It is important to state that ethno-religious conflicts, particularly in the Middle Belt and northern regions, have a devastating impact on women. These conflicts often arise from long-standing ethnic tensions and religious differences, exacerbated by competition over land and resources. Women are frequently targeted in these conflicts, experiencing violence, displacement, and loss of livelihoods [10].

Also, the Boko Haram insurgency in northeastern Nigeria is one of the most severe conflicts affecting women. Boko Haram’s brutal tactics, including mass abductions, sexual violence, and forced marriages, have garnered international attention. Women and girls are particularly vulnerable to these abuses, which have long-lasting physical and psychological effects. Furthermore, during communal clashes and resource-based conflicts women are the targets. In various parts of Nigeria, communal clashes often revolve around land disputes, resource control, and herder-farmer tensions. These conflicts, prevalent in states like Benue, Taraba, and Kaduna, disrupt communities and displace thousands of women and children. The loss of homes and livelihoods significantly affects women’s ability to provide for their families [17,18].

Women are also affected by political violence, especially during election periods. Political thuggery, assassinations, and post-election violence create an environment of insecurity that disproportionately affects women, limiting their participation in political processes and exposing them to further violence. The impact of the conflict on women cannot be overemphasized. It causes physical violence and sexual exploitation. Women in conflict zones are often subjected to physical violence and sexual exploitation. Rape and other forms of sexual violence are used as weapons of war, leading to severe physical injuries, unwanted pregnancies, and sexually transmitted infections. These experiences not only cause immediate harm but also have long-term health implications. It resulted in displacement and humanitarian crisis for the women. Conflicts in Nigeria frequently result in mass displacement. Women and children constitute a significant portion of the internally displaced population. Displacement exacerbates existing vulnerabilities, as women in camps often face inadequate living conditions, limited access to healthcare, and increased risk of exploitation. Also, it has resulted in economic hardship for women [19-21].

Conflict-induced displacement and disruption of economic activities lead to significant economic hardships for women. Many women lose their means of livelihood and struggle to provide for their families. The destruction of markets, farmlands, and other economic resources further deepens poverty and economic instability among women. Also, the psychological impact of conflict on women is profound. Women who have experienced violence, displacement, and the loss of loved ones often suffer from severe mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The lack of mental health services in conflict zones exacerbates these problems, leaving many women without the support they need [22,23].

There is also disruption of education and healthcare. Conflicts disrupt essential services, including education and healthcare. Many girls drop out of school due to insecurity and displacement, limiting their future opportunities and perpetuating cycles of poverty and dependency. Healthcare services, particularly maternal and reproductive health services, are often severely limited during conflicts, increasing risks for pregnant women and new mothers [24].

Women and Conflict in Plateau, Nigeria

Women in Nigeria are profoundly affected by various forms of conflict, facing physical violence, displacement, economic hardships, psychological trauma, and disruptions to education and healthcare. It has resulted in the physical violence and sexual exploitation. Women in conflict zones are at high risk of physical violence and sexual exploitation. During clashes, women are often targeted for rape and other forms of sexual violence as a tactic of war and intimidation. Such violence has devastating immediate and long-term effects on women’s physical and mental health, leading to trauma, unwanted pregnancies, and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS [25].

Women have encountered displacement and loss of livelihood in Plateau, Nigeria. Ethno-religious conflicts frequently lead to large-scale displacement. Women and children make up the majority of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Plateau State. Displacement disrupts women’s lives profoundly, stripping them of their homes, livelihoods, and social networks. Many displaced women find themselves in IDP camps, where living conditions are often dire, and access to basic necessities like food, clean water, and healthcare is limited. The destruction of property and loss of livelihoods during conflicts disproportionately affect women, who often bear the primary responsibility for their families’ welfare. With traditional agricultural activities disrupted, many women struggle to provide for their children, leading to increased poverty and economic instability. Additionally, women frequently face barriers to accessing financial support and resources needed to rebuild their lives after displacement [26,27].

The psychological impact of conflict on women in Plateau State cannot be overstated. Women who have experienced violence, displacement, and the loss of loved ones often suffer from severe mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [22]. The lack of mental health services exacerbates these problems, leaving many women without the support they need to recover. Conflicts disrupt essential services, including education and healthcare. Women and girls are particularly affected by these disruptions. Many girls drop out of school due to displacement or insecurity, limiting their future opportunities and perpetuating cycles of poverty and dependency. Healthcare services, especially maternal and reproductive health services, are often severely limited during conflicts, increasing risks for pregnant women and new mothers [24].

Health of Women in IDP Camps

Internally displaced persons (IDPs) camps are temporary shelters established to accommodate people who have been forced to flee their homes due to conflict, violence, or natural disasters. In many regions, including Nigeria, women make up a significant portion of the IDP population. The health of women in IDP camps is a critical issue, as they face numerous challenges that impact their physical, mental, and reproductive health. There are physical health challenges that women go through. There is poor living condition for women in IDP camps. IDP camps are often overcrowded and lack adequate sanitation facilities, which contribute to the spread of infectious diseases. Women in these camps are at heightened risk of contracting illnesses such as cholera, malaria, and respiratory infections due to poor hygiene and limited access to clean water [21].

Also, there is limited access to healthcare services in IDP camps. Access to healthcare services in IDP camps is often severely limited. Health facilities are typically understaffed and under-resourced, making it difficult for women to receive the care they need. This is particularly problematic for pregnant women and those with chronic health conditions. The lack of access to maternal healthcare services increases the risk of complications during pregnancy and childbirth, leading to higher maternal and infant mortality rates [28].

Furthermore there is malnutrition affecting women in IDP camps. Food insecurity is a common issue in IDP camps, where food supplies are often insufficient and lack nutritional diversity. Malnutrition is a significant health concern, particularly for pregnant and lactating women, who require increased nutritional intake. Malnourished women are more susceptible to health complications and have a higher risk of giving birth to underweight babies [29].

The mental health challenges of women cannot be underestimated. It has resulted in psychological trauma. The experiences that lead to displacement, such as violence, loss of family members, and destruction of homes, are traumatic. Women in IDP camps often suffer from severe psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The lack of mental health services in these camps exacerbates the problem, leaving many women without the support they need to cope with their trauma [23].

It has led to increased gender-based violence. Women in IDP camps are at increased risk of gender-based violence (GBV), including domestic violence, sexual harassment, and rape. The lack of security and privacy in these camps makes women vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. GBV has profound impacts on women’s physical and mental health, leading to injuries, psychological trauma, and sexually transmitted infections [25].

There is the reproductive health challenge facing women. There is the lack of reproductive health services such as family planning, prenatal care, and childbirth assistance, are often inadequate in IDP camps. This lack of services leads to high rates of unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortions, and complications during childbirth. Women in IDP camps frequently lack access to contraception and other reproductive health supplies, further exacerbating these issues [28]. Also, there is the inadequate menstrual health management. Managing menstrual health in IDP camps is a significant challenge. Women often lack access to sanitary products, clean water, and private spaces to manage their menstruation, leading to poor menstrual hygiene. This can result in infections and other health complications, as well as contribute to feelings of shame and embarrassment [30].

Recommendation

Finding a roadmap towards solving the impact of ethno-religious crisis in plateau state requires a coordinated effort that combines healthcare, protection, mental health support, and empowerment initiatives is essential to address the complex challenges faced by these women. There is the need for the state government of Plateau state to collaborate with non-governmental organization and faith-based in supporting women affected by conflict in Nigeria. These organizations will assist in providing essential services, including food aid, healthcare, psychosocial support, and educational programs. There is also the need to strengthen healthcare infrastructure. This could be done through an expansion of healthcare facilities in IDP camps. This could be done through the increase in the number and capacity of healthcare facilities in conflict-affected areas to ensure accessible and adequate medical care for women. There is also the need for the government, NGO’s and FBO’s to ensure that healthcare centers where sick and displaced women are kept are well-equipped with necessary medical supplies and staffed by trained healthcare professionals, particularly those skilled in trauma care and reproductive health services.

The importance of mobile health clinic cannot be overemphasized. There is the need to deploy mobile health clinics to reach women in remote or insecure areas, providing essential services such as vaccinations, prenatal and postnatal care, and treatment for injuries and infectious diseases. Also, there is the need to implement comprehensive psychosocial support programs to address the mental health needs of women affected by conflict. These programs should include counseling, support groups, and trauma-informed care. Furthermore, training for healthcare workers is paramount. Train healthcare workers in mental health care to recognize and treat conditions such as PTSD, depression, and anxiety among women in conflict zones.

There is the need to improve reproductive health services. Access to reproductive health Supplies should be improved. Furthermore, ensure that women in conflict areas have access to reproductive health supplies, including contraceptives, sanitary products, and safe childbirth kits. Also, establish safe spaces within IDP camps and affected communities where women can receive reproductive health services and information in a secure and private environment.

There is the need to strengthen protection mechanisms within IDP camps and conflict-affected communities to prevent gender-based violence. This includes improving security, increasing the presence of female security personnel, and implementing zero-tolerance policies against perpetrators of physical and sexual violence against women in IDP camps. There is the need to provide medical care, legal assistance, and psychosocial support for women in IDP camps.

Conclusion

The ethno-religious conflict in Plateau State, Nigeria, has had a profound and detrimental impact on the health of women in the region. The violence and instability have exacerbated physical, mental, and reproductive health issues, creating a public health crisis that demands urgent attention. Women in Plateau State face heightened risks of injury, malnutrition, and infectious diseases due to disrupted living conditions and inadequate access to healthcare. Additionally, the psychological toll of conflict, including stress, anxiety, and PTSD, has severely impacted their mental health. Reproductive health has also suffered, with limited access to essential prenatal and postnatal care, and a rise in instances of sexual violence. To address these challenges, it is imperative to strengthen healthcare infrastructure, enhance mental health support, and improve reproductive health services. Protection mechanisms must be fortified to prevent gender-based violence, and comprehensive support must be provided for survivors. Ensuring food security and nutrition is crucial for the overall health and resilience of women and their families. A multi-sectoral approach that promotes collaboration between government agencies, NGOs, international organizations, and local communities is essential for holistic and sustainable solutions. Policy advocacy and robust monitoring and evaluation systems are needed to ensure effective implementation and continuous improvement of interventions. By addressing the health needs of women in conflict-affected areas comprehensively, stakeholders can work towards mitigating the adverse effects of ethno-religious conflict and enhancing the overall well-being of women in Plateau State. The commitment to peace-building, healthcare access and women’s empowerment will pave the way for a healthier, more resilient community. The ethno-religious conflict in Plateau, Nigeria, has profound and far-reaching impacts on the health of women. By implementing these recommendations, stakeholders can work towards mitigating these effects and improving the overall health and well-being of women in conflict-affected areas. A coordinated effort that combines healthcare, protection, mental health support, and empowerment initiatives is essential to address the complex challenges faced by these women.

References

- Ikelegbe A (2005) The economy of conflict in the oil rich Niger Delta region of Nigeria. Nordic Journal of African Studies 14(2): 208-234.

- Pogu J (2018) Ethno-religious crises and the challenges of sustainable development in Nigeria. African Journal of History and Culture 10(5): 54-62.

- Human Rights Watch (2013) Leave Everything to God: Accountability for Inter-Communal Violence in Plateau and Kaduna States, Nigeria. Human Rights Watch.

- Onifade CA, Imhonopi D (2013) Towards national integration in Nigeria: Jumping the hurdles. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences 3(9): 75-82.

- Adebayo AA (2011) The challenge of poverty alleviation in Nigeria. Poverty Alleviation Strategies and Sustainable Development in Nigeria 3: 45-54.

- Danfulani UHD, Fwatshak SU (2002) The September 2001 Events in Jos, Nigeria. African Affairs 101(403): 243-255.

- Best SG (2007) Conflict and Peace Building in Plateau State, Nigeria. Spectrum Books.

- Blench R (2004) Natural Resource Conflicts in North-Central Nigeria: A Handbook and Case Studies. Mallam Dendo Ltd.

- Egwu S (2004) Ethnic and Religious Violence in Nigeria. St Stephen Book House.

- Salawu B (2010) Ethno-religious conflicts in Nigeria: Causal analysis and proposals for new management strategies. European Journal of Social Sciences 13(3): 345-353.

- Higazi A (2011) The Jos Crisis: A Recurrent Nigerian Tragedy. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- International Crisis Group (2012) Curbing Violence in Nigeria (I): The Jos Crisis. International Crisis Group.

- Okoli AC, Atelhe GA (2014) Nomads Against Natives: A Political Ecology of Herder/Farmer Conflicts in Nasarawa State, Nigeria. American International Journal of Contemporary Research 4(2): 76-88.