DOI: 10.31038/CST.2016125

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this work was to specify the epidemiological profile of soft tissue sarcomas at the Dakar Cancer Institute and to evaluate their diagnostic and therapeutic management.

Patients and Methods: This was a prospective study involving 40 patients with soft tissue sarcomas treated at the Dakar Cancer Institute during a 3-year period from August 1, 2009 to July 30, 2012.

Results: Soft tissue sarcoma represents 0.4% of cancer cases at the Dakar Cancer Institute. The average age was 41.2 years. The sex ratio was 0.6. There was a family history of cancer in 5 patients. History of type 1 neurofibromatosis was found in 2 patients and irradiation for pelvic cancer in 1 patient. The average time for consultation was 17.2 months. The most frequent localizations were the thigh (17.5%) and the shoulder (12.5%). The mean lesion size was 14.3 cm. Imaging showed metastasis in 9 patients (24.4%) and extension to neighboring organs in 17 patients (42.5%). The most common histological type was Rhabdomyosarcoma (20%) followed by Dermatofibrosarcoma (17.5%). High grade sarcoma was found in 5 patients (12.5%). Excision was the most common type of surgery (30%). Chemotherapy was performed in 13 patients (32.5%) including 8 cases of palliative chemotherapies. Radiotherapy was performed in 5 patients (12.5%). The goal was neo adjuvant in 2 patients, adjuvant in 1 patient and palliative in 2 patients. After a 52-month follow-up period, 1 patient presented a local recurrence and 18 patients died.

Keywords

sarcoma; surgery; chemotherapy; radiotherapy; recurrence.

Introduction

Soft tissue sarcomas represent all malignant tumors with mesenchymal differentiation in all extra-bone tissues with the exception of lymph nodes and glial tissue [1]. It is a rare cancer. The prognosis depends on the initial stage, the histological type, the grade, the location and the initial treatment [2]. The objective of this work was to specify the epidemiological profile of soft tissue sarcomas at the Dakar Cancer Institute and to evaluate their diagnostic and therapeutic management.

Patients and methods

We carried out a descriptive prospective study involving 40 patients with soft-tissue sarcomas treated at the Dakar Cancer Institute for a period of 3 years from August 1, 2009 to July 30, 2012.

Results

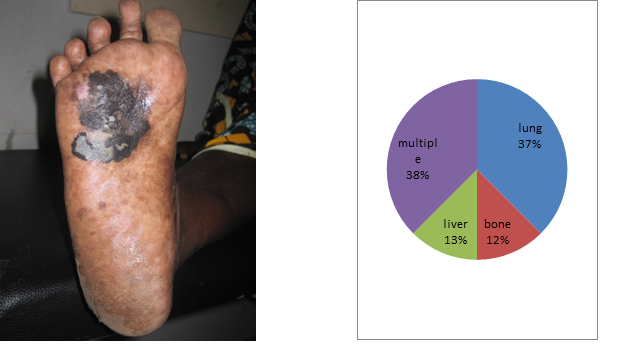

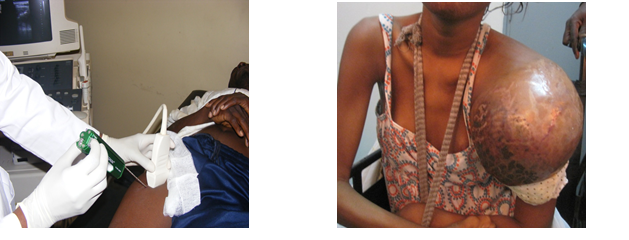

Soft tissue sarcoma represents 4 patients per 1000 cases at the Dakar Cancer Institute. The mean age was 41.2 years with extremes of 9 and 81 years. There was a female predominance with a sex ratio of 0.6. There was a family history of cancer in 5 patients. History of type 1 neurofibromatosis was found in 2 patients and irradiation for pelvic cancer in 1 patient. Mean follow-up was 17.2 months after onset of symptomatology. The most frequent localizations were the thigh (n = 7) [Figure 1] and the shoulder (n = 5) [Figure 2]. The size of the lesions varied from 5 to 35 cm with an average of 14.3 cm. The majority of patients (n = 37) had a single lesion. The initial lesion was bifocal in 2 patients and 1 patient had 4 lesions. The imaging assessment used CT for 20 patients, MRI for 11 and ultrasound in 6 cases. It showed the presence of metastasis in 9 patients (24.4%) at the time of diagnosis and an extension to neighboring organs in 17 patients. Surgical biopsy was the most common modality (26 cases, 67%) followed by ultrasound guided biopsy (6 cases, 15%). The most common histological type was Rhabdomyosarcoma (20%) followed by Dermatofibrosarcoma (17.5%) [Table 1]. A high-grade sarcoma was found in 19 patients (47.5%). Surgery was performed in 24 patients (60%). Wide resection was the most common type of surgery (n = 12). Chemotherapy was performed in 13 patients including 8 palliative chemotherapies. The Adriamycin-Cisplatin chemotherapy protocol was the most widely used (n = 11). Radiotherapy was performed in 5 patients. The goal was neo adjuvant in 2 patients, adjuvant in 1 patient and palliative in 2 patients. After a 52-month follow-up period, 2 patients had local recurrence and 18 patients died [Table 2].

Fig1.deep limb localization Fig2.shoulder localization of a rhabdomyosarcoma

Table 1. Different histologic types of STS

| Histologic type | Frequencies | Percentage (%) |

| Angiosarcoma | 1 | 2,5 |

| Chondrosarcomea | 1 | 2,5 |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans | 7 | 17,5 |

| Fibrosarcoma | 5 | 12,5 |

| Atypical Fibroxantoma | 1 | 2,5 |

| Atypical Hémangioendothelioma | 1 | 2,5 |

| Endemic Kaposi Sarcoma | 1 | 2,5 |

| Leimyosarcoma | 1 | 2,5 |

| Liposarcoma | 2 | 5,0 |

| Neurosarcoma | 3 | 7,5 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 8 | 20 |

| Fusiform Cells Sarcoma | 3 | 7,5 |

| Phyllod Sarcoma | 1 | 2,5 |

| Pleomorph Sarcoma | 2 | 5 |

| Synovialosarcoma | 3 | 7,5 |

| Total | 40 | 100 |

Table 2. Results of follow up

| Evolution | Frequencies | Percentage(%) |

| Décès | 18 | 45 |

| Récidive | 2 | 5 |

| Patients en cours de traitement | 7 | 17,5 |

| Patients traités sans récidive | 13 | 32,5 |

| Total | 40 | 100 |

Discussion

Soft tissue sarcoma (STS) accounts for 0.5-1% of malignant tumors in adults. Their incidence is estimated at 30 cases per million inhabitants [1]. The frequency of soft tissue sarcomas increases in adults with age, and half of the patients are older than 50 years [2]. There is a slight male predominance especially after 60 years [3]. Several genetic factors including Gardener syndrome, Li Fraumeni syndrome and type 1 neurofibromatosis predispose to the onset of STS [4]. The sarcomas of the limbs represent approximately 60% of the sites, 45% of which are in the lower limbs [5, 6]. They are characterized by their large sizes [7,8]. It is a very lymphophilic tumor in the higher grades, in the associated forms in particular carcinosarcomas and in certain histological types such as synovialosarcomas and rhabdomyosarcomas [9]. One patient in four is metastatic at the time of diagnosis and secondary lesions are predominantly located at lymph nodes and lungs [10, 11]. MRI is the main method of imaging in STS. In association with PET-SCAN, its role is increased in the diagnosis of recurrences [12, 13]. The scanner is only used in the local assessment if MRI is contraindicated. Ultrasound is of limited utility except in the superficial small masses. The delay of consultation, very long in case of limited resources are bad prognoses factors [2]. The most frequent histological types are liposarcomas, leiomyosarcomas and malignant histiocytofibromas [14].

The treatment need a multidisciplinary approach and is better considered in a reference center [2]. Surgery regardless of location is the basic treatment. It is more functional and more conservative thanks to multidisciplinary teams and the development of new techniques like the isolated perfusion of the limb. The objective is to minimize functional sequelae and amputation rates [15, 16]. Chemotherapy occupies an important place in neo adjuvant situation in the locally advanced sarcomas and the high grades [2]. The question of adjuvant chemotherapy is generally left to the appreciation of multidisciplinary consultations [17]. Radiotherapy, in particular radio chemotherapy, has produced encouraging results in the neo-adjuvant period for locally advanced tumors [18]. The surgical excision followed by complementary radiotherapy is the standard loco regional treatment of limbs and operable and localized STS [19]. Abstinence from adjuvant radiotherapy is possible for superficial or strictly intramuscular tumors for which surgery showed clear margins [20].

The best survival rate, obtained in the reference centers, is of the order of 60 to 70% at 5 years in the early stages and of 2 months in the advanced stages [2, 11].

Conclusion

Soft tissue sarcoma is a rare cancer. It occurs sporadically or on specific genetic situations. Histological forms and grade determine susceptibility to treatment and prognosis. High grade and long delay are the cause of poor prognosis in limited resources situations. The main goal is first conservative and functional treatment. It needs multidisciplinary approach associating mainly surgery and radiotherapy. High grade sarcomas and metastatic stages have very poor prognosis.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Source of funding: None.

Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Acknowledgments: None.

Author Contribution: Ka conceived this presentation while Diouf and Dem participated in quality control of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Fletcher DM, Unnik K and Mertens F (2002) World Health Organization classification of tumors. Pathology and genetics of tumors of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press.

- Honoré C, Méeus P, Stoeckle E, Bonvalot S (2015) Soft tissue sarcoma in France in 2015: Epidemiology, classification and organization of clinical care. J Visc Surg 152: 223-230. [crossref]

- Jørgensen PH, Lausten GS, Pedersen AB (2016) The Danish Sarcoma Database. Clin Epidemiol 8: 685-690. [crossref]

- Ducimetière F, Lurkin A, Ranchère-Vince D, Decouvelaere AV, Isaac S, et al. (2010) [Incidence rate, epidemiology of sarcoma and molecular biology. Preliminary results from EMS study in the Rhône-Alpes region].Bull Cancer 97: 629-641. [crossref]

- Chang AE, Rosenberg SA (1988) Clinical evaluation and treatment of soft tissue tumors. In: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Soft tissue tumors (2nd ed) St Louis, Toronto, London: CV Mosby Co 19–42.

- Coindre JM, Terrier P, Bui NB, Bonichon F, Collin F, Le Doussal V (1996) Prognostic factors in adult patients with locally controlled soft tissue sarcoma. A study on 546 patients from the French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group. J Clin Oncol 14:869–77.

- Mazeron JJ, Suit HD (1987) Lymph nodes as sites of metastases from sarcomas of soft tissue. Cancer 60: 1800-1808. [crossref]

- Pisters PW, Harrison LB, Leung DH, Woodruf JM, Casper ES (1996) Long-term results of a prospective randomized trial of adjuvant chemotherapy therapy in soft tissue sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 14:859–68.

- Davis CH, Yammine H, Khaitan PG, Chan EY, Kim MP (2016) A multidisciplinary approach to giant soft tissue sarcoma of the chest wall: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 28:211-213.

- Christie-Large M, James SL, Tiessen L, Davies AM, Grimer RJ (2008) Imaging strategy for detecting lung metastases at presentation in patients with soft tissue sarcomas. Euro Journ Cancer 44: 1841-45.

- Marudanayagam R, Sandhu B, Perera MT, Bramhall SR, Mayer D, et al. (2011) Liver resection for metastatic soft tissue sarcoma: an analysis of prognostic factors.Eur J Surg Oncol 37: 87-92. [crossref]

- Choi YY, Lee IS, Kim SJ, Kim JI, Choi KU, et al. (2013) Analyses of short-term follow-up MRI and PET-CT for evaluation of residual tumour after inadequate primary resection of malignant soft-tissue tumours.Clin Radiol 68: 117-124. [crossref]

- Shapeero LG (1990) MRI of the foot and ankle. In: Gooding CR editor, Diagnostic radiology. San Francisco: University of California Press 454–66.

- Ferté C, Pascal LB, Penel N (2009) [Prognostic and predictive factors of soft tissue sarcoma: a daily use of translational research].Bull Cancer 96: 451-460. [crossref]

- Stoeckle E, Italiano A, Stock N, Kind M, Kantor G, et al. (2008) [Surgical margins in soft tissue sarcoma]. Bull Cancer 95: 1199-1204. [crossref]

- Aisen AM, Martel W, Braunstein EM, McMillin KI, Phillips WA, et al. (1986) MRI and CT evaluation of primary bone and soft-tissue tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 146: 749-756. [crossref]

- Fayette J, Blay JY, Ray-Coquard I (2006) [Soft tissues sarcomas: good medical practices for an optimal management]. Cancer Radiother 10: 3-6. [crossref]

- Casali P, Jost L, Sleijfer S, Verweij J, Blay JY (2008) Soft tissue sarcomas: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 19:89-93.

- Cheng EY, Dusenbery KE, Winters MR, Thompson RC (1996) Soft tissue sarcomas: preoperative versus postoperative radiotherapy. J Surg Oncol 61: 90-99. [crossref]

- Suit HD, Mankin HJ, Wood WC, Proppe KH (1985) Preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative radiation in the treatment of primary soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer 55:2659-67.