DOI: 10.31038/CST.2024913

Abstract

This study examines the growing anti-Semitism on the Berkeley campus. The article combines simulations of anti-Semitic attitudes with AI proposed solutions. The technique is based on Mind Genomics, which searches for attitudes in the population. These mindsets are various approaches to making judgments based on the same data or information. The research demonstrates the benefits of mimicking biases while also employing artificial intelligence to provide solutions to such preconceptions.

Introduction – The Growth of Anti-Semitism

The current political climate has fueled anti-Semitism, both locally and globally. Recent years have witnessed an upsurge in hate speech and discriminatory actions, allowing extremist ideologies to spread and gain acceptability. In this toxic environment, anti-Semitic beliefs are more likely to propagate and manifest as threatening and aggressive behavior. The present political context, both locally and globally, has been blamed for some of today’s “newest incarnation” of anti-age-old Semitism’s myths. Recent years have witnessed an upsurge in hate speech and discriminatory actions, allowing extremist ideologies to spread and gain acceptability. In this toxic environment, anti-Semitic beliefs are more likely to propagate and manifest as threatening and aggressive behavior [1-5]. Covert but growing acceptance of anti-Semitism has resulted in an increase in hate speech and acts among certain organizations. As a result, a toxic environment has formed in which individuals feel free to express their anti-Semitic views without fear of repercussions. Furthermore, as both parties have become more entrenched and unwilling to engage in genuine negotiations, the Israeli-Palestinian issue has become more polarized. Anti-Semitism has become stronger in the current political climate, both locally and globally. The rise in hate speech and discriminatory conduct in recent years has provided a forum for extreme ideologies to spread and gain support. Anti-Semitism is more likely to spread in this poisoned climate, showing itself as violent and deadly behaviors [6-11]. Anti-Semitic feelings are common in America, especially among young people. These feelings may be a mirror of larger social problems including xenophobia and the growth of nationalism. In today’s politically sensitive environment, young people could be more vulnerable to the influence of extreme beliefs or extremist organizations. Propaganda and false information demonizing specific groups may also be the source of the hatred and intolerance becoming increasingly public and readily expressed.

Anti-Semitism in Higher Academe, Specifically UC Berkeley

Anti-Semitism has recently increased on college campuses, particularly at UC Berkeley, although it seems to be widespread as of this writing (March 2024). This might be due to a number of causes, including the impact of extremist organizations and the growing polarization of political beliefs. In addition, social media has been used to organize rallies against pro-Israel speakers and propagate hate speech. A lack of education and understanding of the history and consequences of anti-Semitism may contribute to the anti-Semitism pandemic at UC Berkeley. Many students may be unaware of the full ramifications of their words and actions, thereby fueling a vicious cycle of hate and prejudice toward Jews. Furthermore, the university’s failure to respond to and condemn anti-Semitic offenses may have given demonstrators the confidence to act without concerns about negative consequences [12-16]. There are most likely many explanations for the recent surge of anti-Jewish sentiment at the University of California, Berkeley. The ongoing wars in the Middle East, particularly those involving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, might be one direct reason. This has the capacity to elicit strong emotions and generate conflicting views regarding Israel and its activities. Protests and threats against the Israel speaker may have stemmedfrom her apparent sympathy for the Israeli government’s harsh policies or practices. It is possible that university demonstrators responded against the speaker because they considered their affiliations or ideas of view caused unfairness or harm. The timing of this hate campaign may be related to recent events in Israel and its ties with other countries in the region. For example, a disputed decision or action by the Israeli government might reignite interest and support for anti-Semitism. Furthermore, the ubiquity of social media and instant messaging may affect how rapidly information travels and how protests are planned [17-20].

Mind-Sets Emerging from Mind Genomics and Mind-Sets Synthesized by AI

The emerging science of Mind Genomics focuses on the understand of how people make decisions about the everyday issues in their lives, viz., their normal, quotidian existence. Rather than focusing on experiments which put people in artificial situations in order to figure out ‘how they think’, Mind Genomics does simple yet powerful experiments. The different ways people think about the same topic become obvious from the results of a Mind Genomics study.

Mind Genomics studies are executed in a systematic fashion, using experimental design, statistics (regression, clustering) and then interpretation to delve deep into a person’s mind. The “process” of Mind Genomics begins by having the researcher develop questions about the topic, and, in turn, provide answers to those questions. The questions are often called ‘categories’, the answers are often called ‘elements’ or ‘messages.’ The questions deal with the different, general aspects of a topic. They should ‘tell a story’, or at least be able to be put together in a sequence which ‘tells a story’. The requirement is not rigid, but the ‘telling a story’ promotes the notion that there should be a rationale to the questions. In turn, the answers or elements are specific messages, phrases which can stand alone. These elements paint ‘word pictures’ in the mind of the respondent. The process continues, with the respondent reading vignettes, combinations of answers or elements, but without the questions. The respondent reads each vignette, rates the vignette, and at the end the Mind Genomics database comprises a set of vignettes (24 per respondent), the rating of the vignette, and finally the composition of the vignette, in terms of which elements appear in each vignette, and which elements are absent. The final analyses uses OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression to identify which particular elements ‘drive’ the response, as well as cluster analysis to divide the set of respondents into smaller groups based upon the similarity of patterns. Respondents with similar patterns of elements ‘driving’ the response are put into a common cluster. These clusters are called mind-sets. The mind-sets are remarkably easy to name because the patterns of strong performing elements within a mind-set immediately suggest a name for that mind-set.s All of a sudden, this blooming, buzzing confusion comes into clear relief and one sees the rules by which a person weights the different messages to assign the rating [21-25]. The development of mindsets through Mind Genomics leads naturally to the question about the use of artificial intelligence, AI, to synthesize these mindsets. The specific question is whether AI can be told that there are a certain number of mindsets and then instructed to synthesize those mindsets. The difference here is that AI is simply informed about the topic, given an abbreviated ‘introduction, and immediately instructed to create a certain number of mindsets, and of course afterwards answer questions about these mindsets, such as the name of the mindset, a description of the mindset, how the mindset react would to specific messages, slogans with which to communicate with the mind-set, etc. It will be that use of AI which will concern us for the rest of this paper, and especially a demonstration of what can be done with AI using Mind Genomics ‘thinking’ about the mind-sets based upon responses to the issues of the everyday.

A Worked Example Showing the Synthesis of Mind-Sets in Berkeley8803

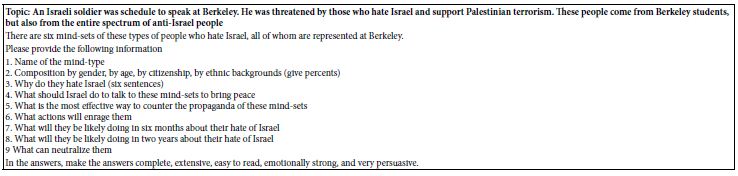

The process begins by briefing AI about the topic. Table 1 shows the briefing given to AI. The specific instantiation of AI is called SCAS (Socrates as a Service.) SCAS is part of the BimiLeap platform for Mind Genomics. The text in Table 1 is typed into SCAS in the Mind Genomics platform. Note that the topic is explained in what might generously be labelled ‘sparsely.’ There is really no specific information.

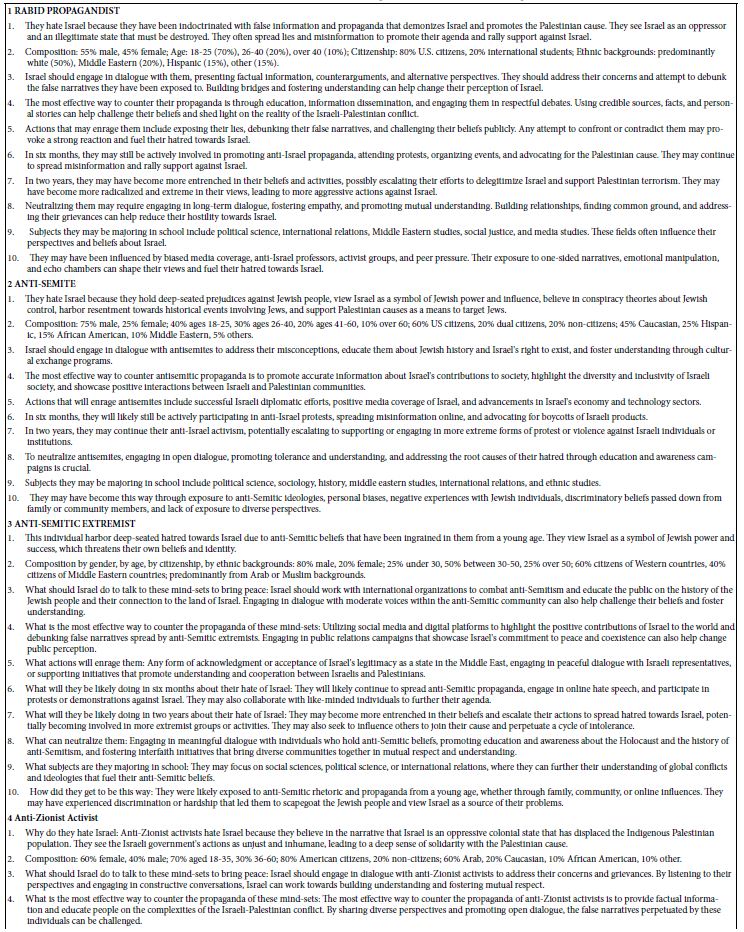

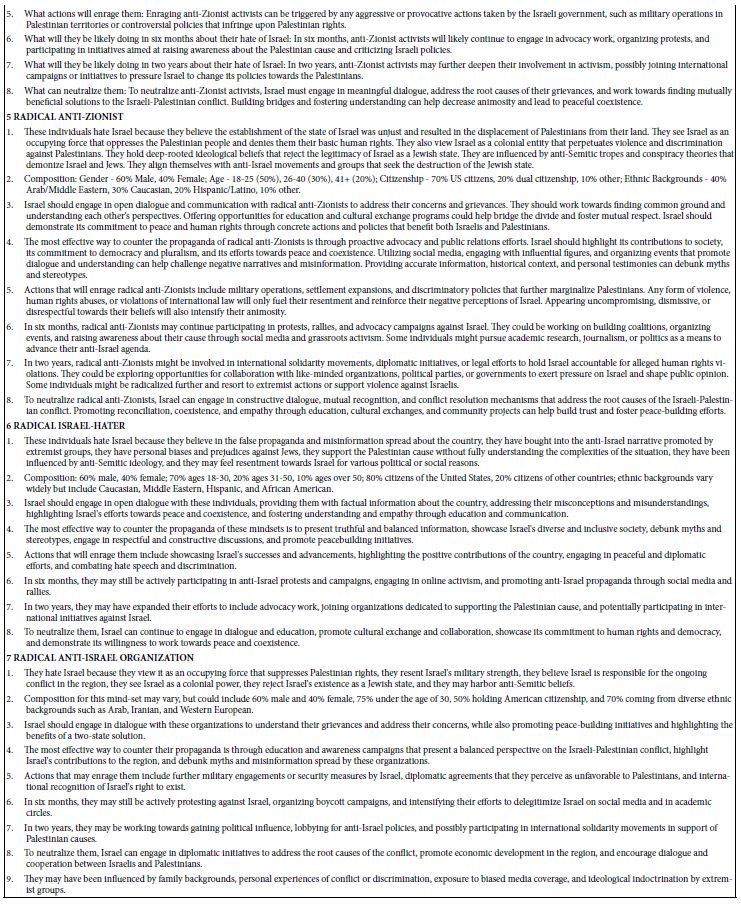

Once the user has briefed SCAS (AI) has been briefed, it is a matter of iterations. Each iteration emerging from the AI ends up dealing with a specific mind-set. Occasionally the iteration fails, and the user has to return to try the iteration once again. The iterations require about 15 to 20 seconds each. The iterations are recorded in an Excel workbook. They are then analyzed after the study has been completed. The user might run 5-10 iterations in a matter of a few minutes. Each iteration, as noted above, is put into a separate tab in the Excel ‘Idea Book’. A secondary set of analyses, built in to the prompted by the user and carried out by AI works on the answers and provides additional insight. Table 2 shows the results from the iterations, generating the mind-sets. Note that the various iterations generated seven mind-sets, not six. The reason is that each iteration generated only one mind-set, even though the briefing in Table 1 specified six mind-sets. Each iteration begins totally anew, without any memory of the results from the previous iterations. The consequence is that SCAS (viz., AI) may return with many more different mind-sets since each iteration generates one mind-set in isolation.

Table 1: The briefing question provided to AI (SCAS)

Table 2: AI Simulation of mind-sets of Berkeley protesters against Israel and an IDF speaker

Benefits from AI Empowered by Mind Genomics Thinking to Synthesize Mind-sets

Mind Genomics allows us to better comprehend the protestors’ individual tastes, values, and views by breaking them down into different mindsets. Having this information is essential for creating communication plans and focused interventions. AI enables us to analyze vast amounts of data and simulate a variety of scenarios. It can decipher complex data and identify patterns and trends that are not immediately apparent to human viewers. Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to help us make better decisions by helping us predict the potential outcomes of certain strategies and actions. Mind Genomics thinking empowering AI Intelligence simulation capabilities can allow us to analyze and understand the different mindsets of the protesters at UC Berkeley. Mind Genomics allows us the idea to segment the protesters based on their unique perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs towards the Israel speaker. This will give us a deeper insight into the underlying motives and triggers of their intolerant behavior. In turn, using AI almost immediately enables us create to virtual scenarios, simulate various perspectives, and then synthesize the array of reactions of the protesters [26]. This real-time synthesis of different mindsets may enable the creation of meaningful, feasible strategies to counter the intolerant antisemitism at a faster pace. Simulating this type of thinking and behavior is meaningful because it allows us to explore a wide range of possibilities and outcomes in a controlled environment. It provides us with valuable insights into the dynamics of group behavior and the factors that drive intolerance and protest movements. By conducting simulations, we can test different strategies and interventions in a risk-free setting and identify the most effective approaches. Rather of falling for artificial intelligence’s tricks, we should use its powers to improve our comprehension and judgment . Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to improve our capacity to evaluate complicated data and model various situations, opening up new avenues for investigation. We can learn more about the actions and motives of the UC Berkeley protestors by fusing the analytical framework of Mind Genomics with the computing capacity of AI. This makes it possible for us to examine the fundamental causes of intolerance and anti-Semitism in academic settings in more detail.

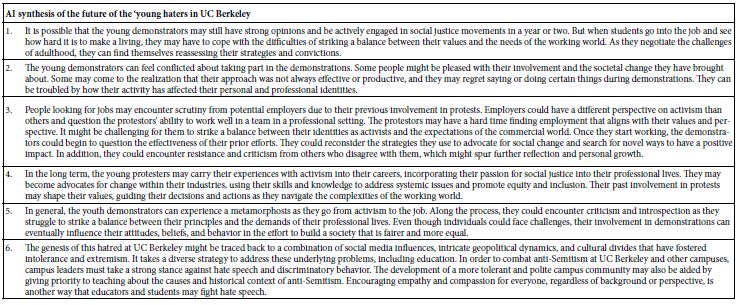

How AI can Synthesize the Future of Future of the Young Haters in UC Berkeley

As a final exercise, AI (SCAS) was instructed to use its ‘knowledge;’ about the mind-sets of students to predict their future. These were called the ‘young haters in UC Berkeley’. The request to AI was to predict their future. The prediction by AI appears in Table 3. It is clear from Table 3 that AI is able to synthesize what might be a reasonable future for the young haters in UC Berkeley. Whether the prediction is precisely correct or not is not important. What is important is the fact that AI can be interrogated to get ideas about the future of students who do certain things, about the nature of mindsets of people who hold certain beliefs, as well as issues which ordinarily would tax one’ thinking and creative juices but might eventually emerge given sufficient effort. The benefit here is that AI can be reduced to iterations, each of which takes approximately 15 seconds, each of which can be further analyzed subsequently by a variety of queries, and which together generate a corpus of knowledge.

Table 3: AI synthesis of the future of the young haters in UC Berkely

Discussion and Conclusions

A House of Social Issues and Human Rights – A Library and Database Located at UC Berkeley

Rather than looking at the negative of the resurgent anti-Semitism at Berkeley, and indeed around the world, let us see whether, in fact, the emergent power of AI can be used to understand prejudice and combat it, just as we have seen what it can do to help us understand the possible sources of the attacks at Berkeley. We are talking here about the creation of a database using AI to understand all forms of the suppression of human rights and to suggest how to reduce this oppression, how to ameliorate the problems, how to negotiate coexistence, how to create a lasting peace. We could call this The house of social issues and human rights, and perhaps even locate it somewhere at Berkeley. What would be the specifics of this proposition? The next paragraphs outline the vision. We may imagine a vast collection paper dealing with the presentation, analysis, discussion, and solution of societal concerns. This library, which is possible to construct in a few months at a surprisingly cheap cost (apart from the people who do the thinking), will be a complete digital platform where people can get resources, knowledge, and answers on urgent social problems from anywhere in the globe. There will be parts of the library devoted to subjects including human rights, environmental sustainability, education, healthcare, and poverty, among others. Articles, research papers, case studies, and other materials will be included in each part to assist readers in comprehending the underlying causes of these problems as well as possible solutions The library will act as a center for cooperation and information exchange, enabling people and communities to benefit from one another’s triumphs and experiences. With this wealth of knowledge at its disposal, the library will enable people to take charge of their own lives and transform their communities for the better. By encouraging individuals to join together and work together to create a more fair and equal society, this library will benefit the whole planet. The library will boost empathy and understanding by encouraging social problem education and awareness, which will result in increased support for underprivileged communities. The library’s use of evidence-based remedies will address structural inequities and provide genuine opportunities.

Books on human rights and world order adorn the shelves of a large library devoted to tackling social concerns globally. Every book includes in-depth assessments and suggested solutions for the problems that humanity now and in the future may confront. The library provides a source of information and inspiration for change, addressing issues ranging from wars and injustices to prejudice and inequality. The collection covers a wide range of topics, including access to education, healthcare, and clean water, as well as gender equality and the empowerment of marginalized communities. It explores the root causes of poverty, violence, and environmental degradation, offering strategies for sustainable development and peacebuilding. The diversity of perspectives and approaches within the library reflects the complexity and interconnectedness of global issues, encouraging dialogue and collaboration among researchers, policymakers, and activists. As visitors navigate the aisles of the library, they discover case studies and success stories from around the world, showcasing innovative solutions and best practices in promoting human rights and fostering a more just and equitable world order. They engage with interactive exhibits and multimedia resources, highlighting the power of storytelling and advocacy in driving social change and building solidarity among diverse populations. The library serves as a hub for research, advocacy, and activism, fostering a sense of collective responsibility and global citizenship among its users. Scholars and practitioners from various fields converge in the library, exchanging ideas, sharing expertise, and mobilizing resources to address pressing social challenges and advance the cause of human rights and justice. They participate in workshops, seminars, and conferences, deepening their understanding of complex issues and sharpening their skills in advocacy, diplomacy, and conflict resolution. The library serves as a catalyst for social innovation and transformative change, inspiring individuals and organizations to unite in pursuit of a more inclusive, peaceful, and sustainable world. Visitors to the library are encouraged to reflect on their own role in promoting human rights and upholding ethical principles in their personal and professional lives. They are challenged to think critically about the impact of their actions on others, and to explore ways in which they can contribute to positive social change and build a more resilient and compassionate society. The library serves as a place of introspection and inspiration, empowering individuals to become agents of change and advocates for justice and equality in their communities and beyond.

References

- Friedman S (2023) Good Jew, Bad Jew: Racism, anti-Semitism and the assault on meaning. NYU Press.

- Gertensfeld M (2005) The deep roots of anti-semitism in European society. Jewish Political Studies Review 17: 3-46.

- Ginsberg B (2024) The New American Anti-Semitism: The Left, the Right, and the Jews. Independent Institute.

- Greenwood H (2020) Corona pandemic opens floodgates for antisemitism. Israel Hayom. March 19, 2020.

- Spektorowski A (2024) Anti-Semitism, Islamophobia and Anti-Zionism: Discrimination and political Construction. Religions 15:74.

- Alexander JC, Adams T (2023) The return of antisemitism? Waves of societalization and what conditions them. American Journal of Cultural Sociology 11: 251-268.

- Jikeli G (2015) European Muslim antisemitism: Why Young urban males say they don’t like jews. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Kushner T (2017) Antisemitism in Britain: Continuity and the absence of a resurgence? In Antisemitism Before and Since the Holocaust, 253-276. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- LaFreniere Tamez HD Anastasio N, Perliger A (2023) Explaining the Rise of Antisemitism in the United States. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, pp.1-22, Taylor & Francis.

- Lewis B (2006) The new antisemitism. The American Scholar 75: 25-36.

- Lipstadt DE (2019) Antisemitism: Here and Now. New York: Schocken.

- Bailard CS, Graham MH, Gross K, Porter E, Tromble R (2023) Combating hateful attitudes and online browsing behavior: The case of antisemitism. Journal of Experimental Political Science, First View, 1-14.

- Kenedy RA (2022) Jewish Students’ Experiences in the Era of BDS: Exploring Jewish Lived Experience and Antisemitism on Canadian Campuses. In Israel and the Diaspora: Jewish Connectivity in a Changing World (pp. 183-204). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Harizi A, Trebicka B, Tartaraj A, Moskowitz H (2020) A mind genomics cartography of shopping behavior for food products during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Medicine and Natural Sciences 4: 25-33.

- Burton AL (2021) OLS (Linear) regression. The Encyclopedia of Research Methods in Criminology and Criminal Justice 2: 509-514.

- Fishman AC (2022) Discrimination on College Campuses: Perceptions of Evangelical Christian, Jewish, and Muslim Students: A Secondary Data Analysis (Doctoral dissertation, Yeshiva University).

- Al Jazeera (English) (2024) US rights group urges colleges to protect free speech amid Gaza war.” Al Jazeera English, 1 Nov. 2023, p. NA. Gale Academic OneFile.

- Wu T, He S, Liu J, Sun S, Liu K, Han QL, Tang Y et al. (2023) A brief overview of ChatGPT: The history, status quo and potential future development. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 10: 1122-1136.

- Radványi D, Gere A, Moskowitz HR (2020) The mind of sustainability: a mind genomics cartography. International Journal of R&D Innovation Strategy (IJRDIS) 2: 22-43.

- Papajorgji P, Moskowitz H (2023) The ‘Average Person ‘Thinking About Radicalization: A Mind Genomics Cartography. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology 38: 369-380. [crossref]

- Shapiro I (2024) Even Jew-haters have Free Speech, But … inFOCUS, 18, 10+. Gale Accessed 29 Feb. 2024.

- Papajorgji P, Ilollari O, Civici A, Moskowitz H (2021) A Mind Genomics based cartography to assess the effects of the COVID19 pandemic in the tourism industry. WSEAS Transactions on Environment and Development 17: 1021-1029.

- Mulvey T, Rappaport SD, Deitel Y, Morford T, DiLorenzo A, et al. (2024) Using structured AI to create a Socratic tutor to promote critical thinking about COVID-19 and congestive heart failure Advances in Public Health, Community and Tropical Medicine APCTM-195 ISSN 2691-8803

- Milligan GW, Cooper MC (1987) Methodology review: Clustering methods. Applied Psychological Measurement 11: 329-354.

- Nassar M (2023) Exodus, nakba denialism, and the mobilization of anti-Arab Racism. Critical Sociology 49: 1037-1051.

- Lonas, Lexi (2023) “Palestinian Student Group At Center of Antisemitism, Free Speech Debate: SJP chapters said the world witnessed ‘a historic win for the Palestinian resistance: across land, air, and sea, our people have broken down the artificial barriers of the Zionist entity.’.” Hill, 16 Nov. 2023, p. 11. Gale Academic OneFile.