Abstract

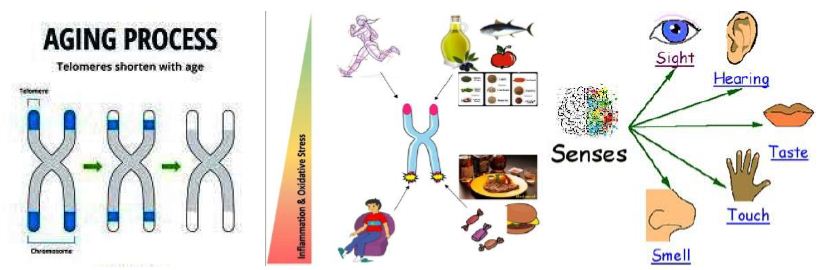

Stress cognitions are important for survival, but if they are based on distorted perceptions, they may promote excessive stress arousal, creating a harmful milieu for cellular longevity. While in contrast, emotions based on ‘false projections’ or fear-based beliefs are harmful to longevity of your life. We speculate that certain types of meditation can increase awareness of present moment experience leading to positive cognitions, primarily by increasing meta-cognitive awareness of thought, a sense of control (and decreased need to control), and increased acceptance of emotional experience. These cognitive states and skills reduce cognitive stress and thus ability for more accurate appraisals, reducing exaggerated threat appraisals and rumination, and distress about distress. These positive states are thus stress-buffering. Increasing positive states and decreasing stress cognitions may in turn slow the rate of cellular aging. There is some indirect support of aspects of this hypothesis involving stress cognitions. In our previous study, perceived life stress – primarily an inability to cope with demands and feeling a lack of control, and higher nocturnal stress hormones (cortisol and catecholamines) were related to shorter telomere length. Trait negative mood was related to lower telomerase activity, a precursor of telomere shortening. Here we presented preliminary data from the same sample linking telomere length to higher proportions of challenge appraisals relative to threat appraisals in response to a standardized stressor. The results suggest that the relative balance of threat to challenge cognitions may be important in buffering against the long term wear and tear effects of stressors. To the extent that meditation mitigates stress-related cognitions and propagation of negative emotions and negative stress arousal, a longstanding practice of mindfulness or other forms of meditation may indeed decelerate cellular aging. We also speculate about the physiological mechanisms. Above we have reviewed data linking stress arousal and oxidative stress to telomere shortness. Meditative practices appear to improve the endocrine balance toward positive arousal (high DHEA, lower cortisol) and decrease oxidative stress. Thus, meditation practices may promote mitotic cell longevity both through decreasing stress hormones and oxidative stress and increasing hormones that may protect the telomere. There is much evidence of neuroendocrine and physical health benefits from TM, which has a longer history of study than MBSR. The newer studies of mindfulness meditation are promising, and offer insight into specific cognitive processes of how it may serve as an antidote to cognitive stress states. This field of stress induced cell aging is young, our model is highly speculative, and there are considerable gaps in our knowledge of the potential effects of meditation on cell aging. Several laboratories are working on diverse aspects of this model, which will soon allow it to be evaluated in light of the empirical data.

Older adults, those aged 60 or above, make important contributions to society as family members, volunteers and as active participants in the workforce. While most have good mental health, many older adults are at risk of developing mental disorders, neurological disorders or substance use problems as well as other health conditions such as diabetes, hearing loss, and osteoarthritis. Furthermore, as people age, they are more likely to experience several conditions at the same time. Globally, the population is ageing rapidly. Between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world’s population over 60 years will nearly double, from 12% to 22%. Mental health and well-being are as important in older age as at any other time of life. Mental and neurological disorders among older adults account for 6.6% of the total disability (DALYs) for this age group. Approximately 15% of adults aged 60 and over suffer from a mental disorder. The world’s population is ageing rapidly. Between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world’s older adults is estimated to almost double from about 12% to 22%. In absolute terms, this is an expected increase from 900 million to 2 billion people over the age of 60. Older people face special physical and mental health challenges which need to be recognized. Over 20% of adults aged 60 and over suffer from a mental or neurological disorder (excluding headache disorders) and 6.6% of all disability (disability adjusted life years-DALYs) among people over 60 years is attributed to mental and neurological disorders. These disorders in older people account for 17.4% of Years Lived with Disability (YLDs). The most common mental and neurological disorders in this age group are dementia and depression, which affect approximately 5% and 7% of the world’s older population, respectively. Anxiety disorders affect 3.8% of the older population, substance use problems affect almost 1% and around a quarter of deaths from self-harm are among people aged 60 or above. Substance abuse problems among older people are often overlooked or misdiagnosed. Mental health problems are under-identified by health-care professionals and older people themselves, and the stigma surrounding these conditions makes people reluctant to seek help.

Risk Factors for Mental Health Problems among Older Adults

There may be multiple risk factors for mental health problems at any point in life. Older people may experience life stressors common to all people, but also stressors that are more common in later life, like a significant ongoing loss in capacities and a decline in functional ability. For example, older adults may experience reduced mobility, chronic pain, frailty or other health problems, for which they require some form of long-term care. In addition, older people are more likely to experience events such as bereavement, or a drop in socioeconomic status with retirement. All of these stressors can result in isolation, loneliness or psychological distress in older people, for which they may require long-term care. Mental health has an impact on physical health and vice versa. For example, older adults with physical health conditions such as heart disease have higher rates of depression than those who are healthy. Additionally, untreated depression in an older person with heart disease can negatively affect its outcome. Older adults are also vulnerable to elder abuse – including physical, verbal, psychological, financial and sexual abuse; abandonment; neglect; and serious losses of dignity and respect. Current evidence suggests that 1 in 6 older people experience elder abuse. Elder abuse can lead not only to physical injuries, but also to serious, sometimes long-lasting psychological consequences, including depression and anxiety (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Dementia and Depression among Older People as Public Health Issues

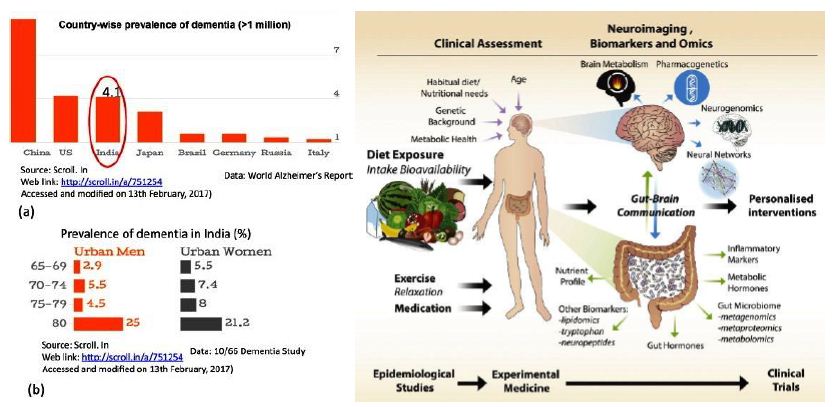

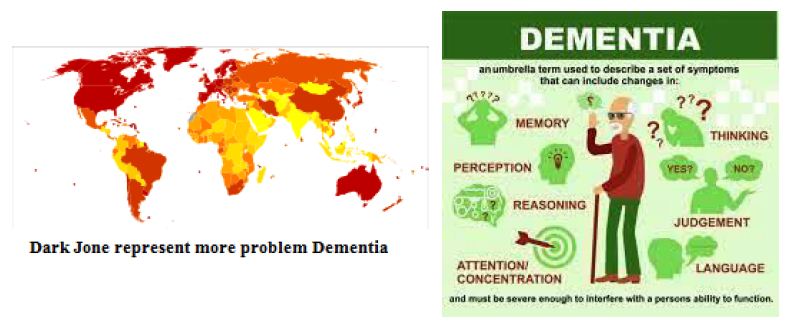

Dementia is the loss of cognitive functioning — thinking, remembering, and reasoning — to such an extent that it interferes with a person’s daily life and activities. Some people with dementia cannot control their emotions, and their personalities may change. It is a syndrome, usually of a chronic or progressive nature, in which there is deterioration in memory, thinking, behaviour and the ability to perform everyday activities. It mainly affects older people, although it is not a normal part of ageing. It is estimated that 50 million people worldwide are living with dementia with nearly 60% living in low- and middle-income countries (Figure 2).

Figure 2

The total number of people with dementia is projected to increase to 82 million in 2030 and 152 million in 2050. There are significant social and economic issues in terms of the direct costs of medical, social and informal care associated with dementia. Moreover, physical, emotional and economic pressures can cause great stress to families and carers. Support is needed from the health, social, financial and legal systems for both people with dementia and their carers (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Depression

Depression can cause great suffering and leads to impaired functioning in daily life. Unipolar depression occurs in 7% of the general older population and it accounts for 5.7% of YLDs among those over 60 years old. Depression is both underdiagnosed and undertreated in primary care settings. Symptoms are often overlooked and untreated because they co-occur with other problems encountered by older adults. Older people with depressive symptoms have poorer functioning compared to those with chronic medical conditions such as lung disease, hypertension or diabetes. Depression also increases the perception of poor health, the utilization of health care services and costs.

Treatment and Care Strategies to Address Mental Health Needs of Older People

It is important to prepare health providers and societies to meet the specific needs of older populations, including:

- Training for health professionals in providing care for older people;

- Preventing and managing age-associated chronic diseases including mental, neurological and substance use disorders;

- Designing sustainable policies on long-term and palliative care; and

- Developing age-friendly services and settings.

Health promotion – The mental health of older adults can be improved through promoting Active and Healthy Ageing. Mental health-specific health promotion for older adults involves creating living conditions and environments that support wellbeing and allow people to lead a healthy life. Promoting mental health depends largely on strategies to ensure that older people have the necessary resources to meet their needs, such as:

- Providing security and freedom;

- Adequate housing through supportive housing policy;

- Social support for older people and their caregivers;

- Health and social programmes targeted at vulnerable groups such as those who live alone and rural populations or who suffer from a chronic or relapsing mental or physical illness;

- Programmes to prevent and deal with elder abuse; and

- Community development programmes.

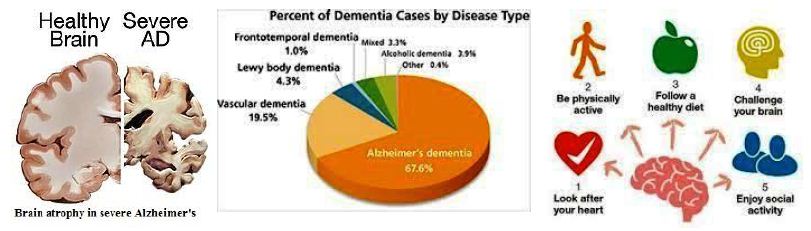

Interventions – Prompt recognition and treatment of mental, neurological and substance use disorders in older adults is essential. Both psychosocial interventions and medicines are recommended. There is no medication currently available to cure dementia but much can be done to support and improve the lives of people with dementia and their caregivers and families, such as:

- Early diagnosis, in order to promote early and optimal management;

- Optimizing physical and mental health, functional ability and well-being;

- Identifying and treating accompanying physical illness;

- Detecting and managing challenging behaviour; and

- Providing information and long-term support to careers.

Mental health care in the community -Good general health and social care is important for promoting older people’s health, preventing disease and managing chronic illnesses. Training all health providers in working with issues and disorders related to ageing is therefore important. Effective, community-level primary mental health care for older people is crucial. It is equally important to focus on the long-term care of older adults suffering from mental disorders, as well as to provide caregivers with education, training and support. An appropriate and supportive legislative environment based on internationally accepted human rights standards is required to ensure the highest quality of services to people with mental illness and their caregivers.

Get Your Finances in Order

Organise your money so you can work out what you’ll have to live on. Gradually reducing your spending in the lead up to retirement will make it easier to adjust. Track down any old pensions, claim your state pension and check what other benefits you can claim (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Wind Down Gently

Ensure a smoother transition by retiring in stages. By easing off your workload over several years, you’ll be able to get used to the idea of not working and fill your time in other ways. Ask your employer if you can cut back your working hours.

Prepare for Ups and Downs

There may be times when you feel lonely or a bit lost, which is normal. If ill health or changes in your relationships temporarily scupper your plans, accept that this has happened and get your back-up plan in action. Think positively and share any concerns with others. Use your free time to continue to challenge yourself mentally, whether it’s learning an instrument or a language or getting a qualification.

Eat well-Make sure you eat regular meals, especially if your previous pattern, while at work, was to snack. Take advantage of the extra time on your hands and explore healthy cooking options. Fruits and vegetables contain many vitamins and minerals that are good for your health. These include vitamins A (beta-carotene), C and E, magnesium, zinc, phosphorous and folic acid. Folic acid may reduce blood levels of homocysteine, a substance that may be a risk factor for coronary heart disease. Homocysteine is a type of amino acid, a chemical your body uses to make proteins. Normally, vitamin B12, vitamin B6, and folic acid break down homocysteine and change it into other substances your body needs. There should be very little homocysteine left in the bloodstream (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Develop a Routine

You may find it feels more normal to continue getting up, eating and going to bed at roughly the same time every day. Plan in regular activities such as voluntary work, exercise and hobbies. This will keep things interesting and give you a purpose.

Exercise Your Mind

Government studies have shown that learning in later years can help people stay independent, so use your free time to continue to challenge yourself mentally, whether it’s learning an instrument or a language or getting a qualification (Figure 6).

Figure 6

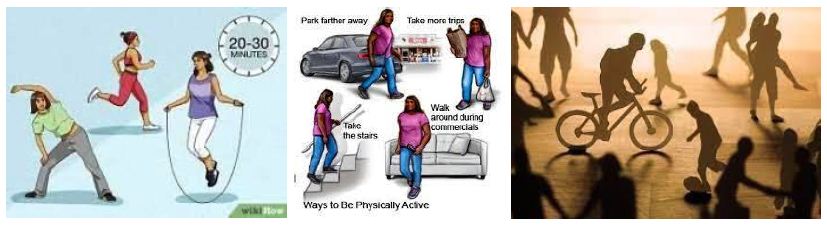

Keep Physically Active

We should all aim to do at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity a week, so build up to this if you haven’t made exercise a normal part of your life previously. Why not sign up for a charity event to give you a goal to work towards ? WHO defines physical activity as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure. Physical activity refers to all movement including during leisure time, for transport to get to and from places, or as part of a person’s work.

Make a List

Writing down your aims may help you focus on what you really want to achieve – like a ‘to do’ list. Work out what you can afford to do and schedule time to make it happen, so you experience a sense of accomplishment, as you would have done at work.

Seek Social Support

For many people, work can form a big part of their social life and it’s common to feel at a bit of a loose end once you retire. Fill the gaps by joining clubs and groups. Find out about the social and physical benefits of walking groups.

Make Peace and Move On

Don’t spend your retirement dwelling on your working days. Accept that you’ve done all you can in that job and focus on your next challenge. You’ve still got lots to achieve.

Go for a Health Check

Prevention is better than cure, and now is the perfect time to get your free midlife MOT. The NHS Health Check programme aims to help prevent heart disease, stroke, diabetes, kidney disease and certain types of dementia. Everyone between the ages of 40 and 74, who has not already been diagnosed with one of these conditions or have certain risk factors, will be invited once every five years to have a check to assess their risk of these age-related illnesses and will be given support and advice to help them reduce or manage that risk. If you’re in this category but haven’t had a check in the last five years, you can ask your GP for one.

Keep in Touch with Your Friends from Work

Just because you are retiring doesn’t mean you have to lose touch with the group of friends you made in your workplace. Why not make arrangements for regular catch-ups ? Or, you might want to use some of your new leisure time to catch up with old friends that you haven’t seen for a while. If you enjoy party planning, find an excuse to get everyone together and have fun arranging the perfect garden or dinner party, anniversary celebration or other special occasion. You could even raise funds for our life saving work at the same time through our “Give in Celebration” funds.

Pamper Yourself

After decades of hard work, you are due some ‘me time’. Whether your idea of indulgence is a city break, a day trip to a spa or a small pleasure like dining out or going to the cinema, schedule some time for a well-deserved treat.

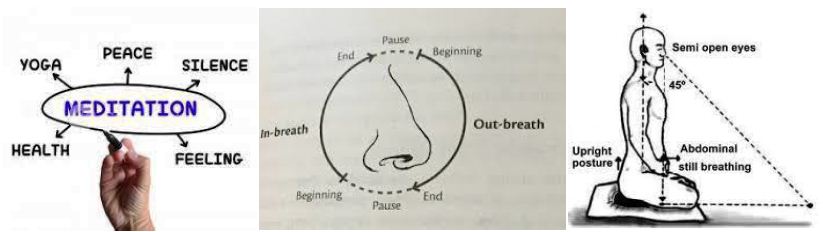

Practise Mindfulness

Practising mindfulness has become more popular than ever in the last decade as a strategy to relieve stress, anxiety and depression. Fresh air and exercise is an instant mood booster and instrumental in maintaining your wellbeing. Research, such as a 2009 study from Goethe University in Germany, has shown that meditation strengthens the hippocampus, the area of the brain that is important for memory, and slows the decline of brain areas responsible for sustaining attention. There are no set guidelines for how often you should meditate for optimal result, but a handful of experiments suggest that a mere 10 to 20 minutes of mindfulness a day can be beneficial—if people stick with it.

Give Back to the Community

Ever thought of volunteering? Perhaps you’d enjoy getting involved with your local youth club, animal rescue centre, environmental organisation or elderly support group. There are plenty of charities that would welcome a helping hand, not least the BHF, of course! We offer the opportunity to help out in our shops, in a furniture or electrical store, with fundraising and at lots of different types of events.

Be One with Nature

Fresh air and exercise is an instant mood booster and instrumental in maintaining your wellbeing. Why not incorporate a walk in the woods or a nearby park into your daily routine? This is an ideal way of achieving the recommended minimum of 150 minutes of physical activity per week.

Travel More

Always dreamt of going on an around-the-world cruise, a wine-tasting trip through Italy, or a simple camping expedition in the Welsh valleys? Now you can finally make those long-held plans a reality, depending on your health and budget limitations. If longer trips aren’t practical, mini breaks may be a good alternative – or even days out to places you’ve never visited before.

Get a New Pet or Partner

Could you house a rescue cat or dog in need of a new home? Research has shown that our furry friends have a positive effect on our health and wellbeing.

Push Your Boundaries

It’s easy to get stuck in a rut, both health-wise and in general, and doing something different can be a refreshing change. Some people have found that simple changes, such as trying a tasty new recipe, finding a different hairdresser or joining an exercise class they haven’t done before gives them a new zest for life.

Take Up a New Project

Finally you have time to get stuck into all those things you’ve been meaning to do but never got round to. Mapping your family tree, building a shed, planting a veg patch… the list goes on, but now you can actually do what you’ve always wanted to. Need inspiration? Have a look at our features on gardening, healthy baking, and cycling groups. Read our feature about retirement. Read how volunteering can help you beat loneliness.

A very recent study tested whether an acute bout of exercise would induce a different response on telomerase activity in older vs. young individuals and whether this response would be gender-specific [1]. To test this hypothesis, age- and gender-related differences in telomerase and shelterin responses at 30, 60, and 90 min after a high intensity interval cycling exercise were determined in PBMC of 11 young (22 years) and 8 older (60 years) men and women. A larger increase in telomerase activity, as assessed by TERT mRNA levels, was found in the young compared to the older group after exercise. The second main finding of that study was the higher TERT response to the acute endurance exercise in men compared to women, in whom the response was negligible, independently of age (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Those results showed that aging is associated with reduced telomerase activation in response to high-intensity cycling exercise in men [1]. Another study showed that a 30-min treadmill running session was long enough to increase PBMC telomerase activity in 22 young healthy subjects including 11 women and 11 men [2]. Altogether, those recent studies confirm that the increasing telomerase activity after a single bout of exercise could be one of the mechanisms by which physical activity protects against aging [2].

We propose that engaging in a healthy diet and regular physical activity could be both promising strategies to protect telomere maintenance and improve health span at old age (Figure 8 and Table 1).

- Find a quiet, comfortable place to sit, with your back upright.

- Put on headphones (this will help block outside distractions).

- Select the meditation length that’s ideal for you.

- Press play and close your eyes. Focus your attention on your breath, breathing in and out.

Figure 8

Table 1: Professional Advantage of Vipassana

|

Sl. No. |

Professional Advantage of Vipassana |

Students |

|

|

N |

% |

||

|

1 |

Developed balanced mind, |

29 |

21.8 |

|

2 |

Control over Tension angry frustration, agitation anxiety, impatience, Reduce stress |

56 |

42.2 |

|

4 |

More empathetic, organized, confidant, orderly and disciplined |

18 |

13.5 |

|

5 |

Objective perception |

11 |

8.3 |

|

6 |

Build good relationship with peers, relatives, and colleague |

7 |

5.3 |

|

7 |

Handle conflict situation |

5 |

3.8 |

|

8 |

Make better decision making |

13 |

9.8 |

|

9 |

Enhance my productivity |

1 |

.8 |

|

10 |

No benefit, Not convinced. Only a spiritual process. |

3 |

2.3 |

|

11 |

Better concentration |

14 |

10.5 |

| Total |

133 |

100.0 |

|

Meditation Reduce depression, tiredness, and fatigue, improve attention, emotion regulation, and mental flexibility. Meditation goes beyond simple relaxation techniques, although that is definitely one of the main benefits. I develop the system called Ven Dr Sumedh Thero system of ordination/Meditation i.e. based on my own experience in India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam by meditating as brain exercise and mental energy conservation [3-5]. The study indicates that the Vipassana Meditation process enhanced their professional skills and approaches. Majority students reported that (42.2%) the awareness process helped them to control over their tensions, anxiety and impatience and reduce their anxiety to perceive things professionally than personally [4].

References

- Cluckey TG, Nieto NC, Rodoni BM, Traustadottir T (2017) Preliminary evidence that age and sex affect exercise-induced hTERT expression. Gerontol 96: 7-11. [crossref]

- Zietzer A, Buschmann EE, Janke D, Li L, Brix M, et al., (2017) Acute physical exercise and long-term individual shear rate therapy increase telomerase activity in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Acta Physiol 220: 251-262. [crossref]

- Ven Sumedh Thero, Kataria HB, Aditya Suman (2022) Meditation for Skin Aging, Reduces Wrinkles and Change Your Appearance? International Journal of Clinical & Experimental Dermatology 7: 8-12.

- Ven Sumedh Thero, Kataria HB, Aditya Suman (2021) How Running Give Us a High Expectations to Overcome Neurological Disorders . Journal of Neurology Research Review & Reports. SRC/JNRRR-157 Volume 3(3): 1-6.

- Ven Sumedh Thero (2021) Family Dynamics and Health in Post Covid-19. Clinical Research and Clinical Case Reports 1.