Abstract

The paper introduces a system to deal with problems of society using SCAS, Socrates as a Service. SCAS is provided with a detailed description of a conventional problem faced by people, and in turn instructed to defined prospective mind-sets in the population who suffer with this problem. SCAS further provides information on the nature of these hypothesized mind-sets, what the mind-sets are thinking, and how the mind-sets would respond to topic-relevant slogans that would be generated to solve the problem. Finally, the paper finishes with the use of SCAS to summarize the issue, provide perspectives that people might have, and identify what next steps need to be taken, as well as innovations that should be introduced which deal with and even solve the problem. SCAS is a general approach. The paper here uses SCAS to investigate the ‘why’ patients fail to keep their doctor’s visits, and what innovations might solve the problem.

Introduction

This paper grew out of the recognition that all too often patients fail to follow the suggestions of their medical and health professionals. The topic of compliance is a large one. The focus of this paper is on the simple problem of patients not showing up at the prescribed time for their follow-up appointments. The damage which ensues can be enormous, impacting the health of the patient, the cost to the medical practice, and the disruption of a system which must accommodate the schedules of a variety of people who then must regroup and update the schedules [1].

When dealing with this problem, we are actually dealing with issues of communication interacting with motivation and habit. How does the medical establishment work with individuals to ensure that they come to scheduled appointments. The importance of this question can be easily understood when one realizes the number of reminder messages which appear on the smartphones of patients, telling them of the upcoming appointment, asking them to ‘e-check in’ and then giving them the chance to cancel and reschedule. This and other actions such as reminder phone call are the obvious effort to minimize the expensive ‘no-shows’. In recent years, the process has been automated, with AI-driven chatbots and voice interactions finding their place in the seemingly impossible to solve conundrum of getting patients to sow for their appointments [2].

The business literature recognizes the problems of ‘no-shows’. The issues underlying the no-shows are extensive, as are the suggestions for improvement. The case of medicine is particular serious for no-shows simply because one cannot necessarily move the appointment to some later time and ‘go from there.’ A person’s health is labile. Moving a scheduled appointment a month or two later, when a slot opens up, may be too late when the issue is the follow up from what can be a serious problem, and when not treated can evolve to a life-threatening one. One serious illness often comes to the fore, diabetes. The consequence of missing a follow up appoint with a doctor when the person has diabetes 2 can be severe [3-6].

The Contribution of Mind Genomics Enhanced by SCAS (Socrates as a Service)

The problem of no-shows was first brought into the world of Mind Genomics through collaboration with physicians in Chicago, IL, specifically anesthesiologist Dr. Glen Zemel. Author Moskowitz collaborated with Dr. Zemel on a variety of studies dealing with the mind of the patient in the hospital. As a practicing anesthesiologist, Zemel often recognized the issues involved in patients who fail to follow up, often even having to forego surgery on the particular scheduled date because either they ‘forgot’ (rare) or forgot to follow the requirements of avoid food for the previous 12 hours and so forth. It was these immediate issues which ended up costing the medical practice many thousands of dollars.

The problem became more acute when authors Braun and Mulvey, and later Cooper, became involved in the issue of patients who failed to follow up at specific times. These individuals suffered from a variety of metabolic disorders; the most common one being diagnosed as pre-diabetic. The failure to return at the scheduled time for a follow-up morphed from being a financial loss to a medical practice into the possibility that diabetes might develop because the pre-diabetic essentially disappeared, but presumably the condition remained with the individual.

The evolution of Mind Genomics into a much deeper use of AI opened up the questions about what SCAS might be able to contribute to an understanding of why people fail to go to follow-up appoints with their doctor after learning that they are suffering from a serious condition. Could AI provide insights, especially with the newly discovered ability to ‘prime’ AI with a detailed background of an issue, and then instruct AI to ‘flesh out’ what might be going on in the mind of a person? As we move through the topics in this paper we must keep in mind that everything presented here regarding ‘thinking’ is the result of instructing Socrates as a Service (SCAS), viz., a version of AI powered by Chat GPT 3.5 [7].

Demonstration: Priming AI to Simulate Poor Patients Living in Public Housing

The remainder of this paper presents the results of a simulation using SCAS (Socrates as a Service, a form of AI growing out of ChatGPT 3.5), and the secondary analysis, viz., AI summarization of the data generated by the SCAS simulation. The important thing to keep in mind is that there is almost no information of any substantive import presented by the user, other than the initial framing of the situation, and what the user wants to ‘discover’ by having AI simulate the answers in place of having a human being do so.

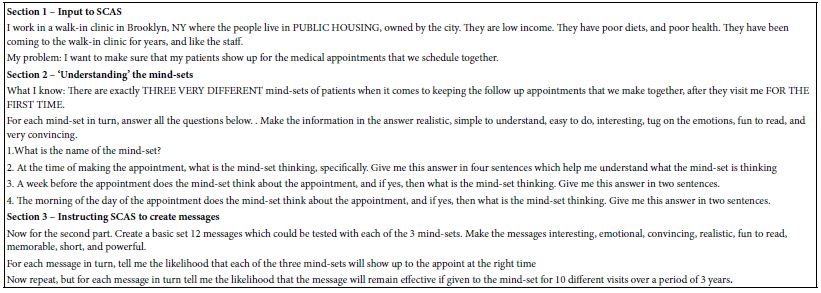

The process begins with the orientation provided to AI, shown in Table 1. The table divides into three sections.

Table 1: The input to Socrates as a Service (SCAS)

Section 1 – Input Information to SCAS

Here, the user creates a general picture of the situation. The input positions the user as a person working in a clinic in a poor area in Brooklyn. One might this simulation with a variety of different so-called general pictures, such as stating that the area is inhabited by upper middle classes, that the person works in a concierge medical service, that the location is somewhere else. With that flexibility the user would be well on the way to parametrically exploring the different alternatives. The opportunities are endless.

Section 2 – Understanding the Mind-sets

Here the user presents SCAS with a minimum amount of information, sufficient however to allow SCAS to create mind-sets. The user does not define the concept of mind-set, nor does the user give any hint about what properties are possessed by the three mind-sets. Given only this minimal amount of information, really only one piece of information, that there are three mind-sets, the system requests AI to create names, and inner thoughts of these three mind-sets.

Section 3 – Request that SCAS Produce 12 Message and Estimate the Performance of Each Message among the Three Mind-sets

The final request generated the desired 12 messages to be evaluated by three mind-sets. It is important to emphasize that nowhere in the instructions is any information presented to SCAS program that could be considered to be a subject-relevant prompt. All of the information generated by SCAS comes from the way SCAS processes the request.

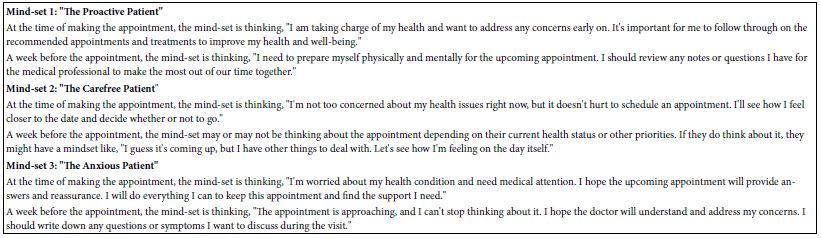

Table 2 present the first part of the output, viz., the three mind-sets, explicated in terms of what each mind-set thinks at the time of making the appointment, and then a week before the appointment. The remarkable thing emerging from Table 2 is the realistic nature of the mind-sets and their thoughts. Once could easily think that these are verbatim quotes emerging from a discussion with the patient about the issue of making and keeping medical appointments.

Table 2: The description of the three mind-sets emerging from SCAS. As noted in the text, SCAS was not given any specific material on mind-sets which to base what it returned to the user.

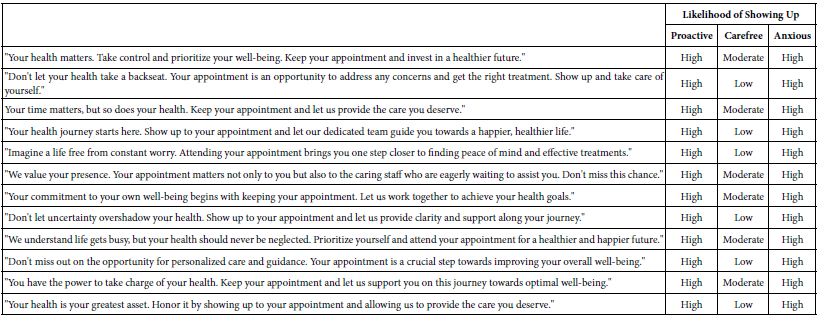

Table 3 shows how each of the three mind-sets would estimate the likelihood of showing up for the follow up medical appointment if the mind-set were to be reminded through the slogan. The slogans were created by SCAS. SCAS ‘predicts’ that all 12 would be effective for Mind-Set 1 (proactive), effective for Mind-Set 3 (Anxious), but not particularly effective for Mind-Set (Carefree). Once again it should be noted that these results make sense. We expected a mind-set named Carefree not to care about any of the messages, and thus not pay attention to follow up messages with the slogans shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Estimated likelihood of showing up for the follow-up appointment, for each of 12 slogans by each of the three mind-groups. Everything was generated by SCAS, using only the input to SCAS shown in Figure 1.

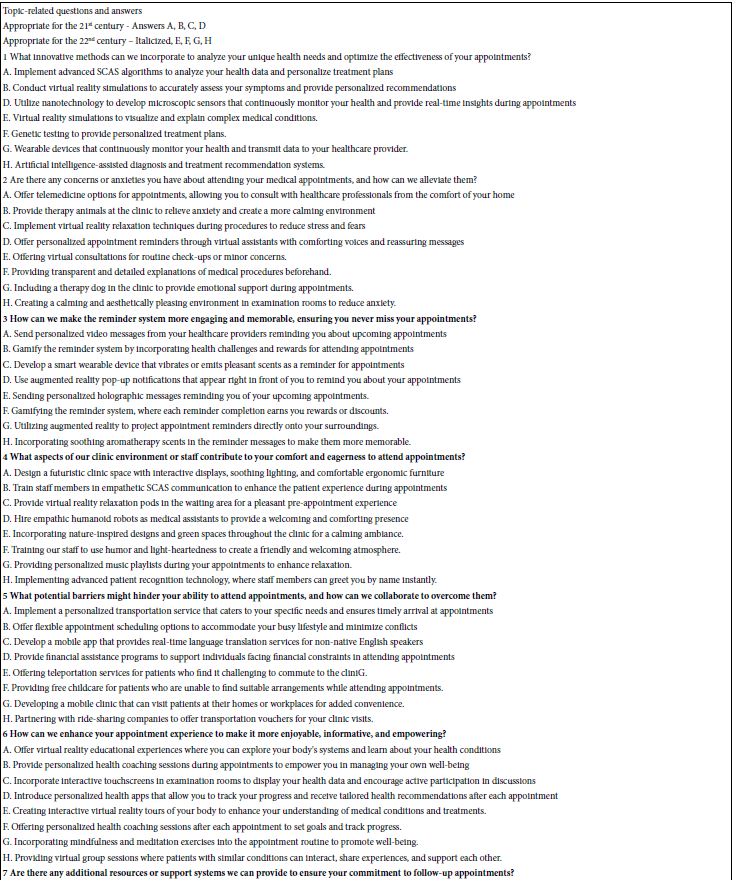

Inventing the Future Using Today’s Topics

The second part of this paper focuses on the use of SCAS to understand what to do in order to improve the compliance of patients regarding their requested follow up visit. The original use of SCAS was to allow the user to type a ‘squib’ or information about a topic and have SCAS return with a set of 15 questions. The same feature was available for SCAS to return 15 answer to a given question. These feature remain in SCAS, and led to an effort to compare the answers to the same questions when SCAS was told that the answers had to be appropriate for the 21st century (now), and then that the answers had to be appropriate for the 22nd century (75 years hence).

The same set of 15 questions was used to compare the answers for the two centuries. The SCAS was primed to provide four separate answers to each of the 15 questions, requiring the answers to be appropriate for the 21st century (Table 4, answers A-D), and then be appropriate for the 22nd century (Tabe 4, answers E-H, italicized). Table 4 suggest that the answers for the 22nd century seem reasonable, and to be extensions of current day technology.

Table 4: Fifteen SCAS-generated topic-related questions about office visits to the medical professional. Each question shows four SCAS-generated questions assuming a year in the 21st century, and then a year in the 22nd century.

Summarization of Information Proposed – Broad Overviews Produced by SCAS

When the Mind Genomics study has been closed, SCAS creates a set of summarizations for each iteration, doing the summarizations separately. These summarizations are returned to the user in an email, usually within a half hour after the close of the study. Thus, in the not-unusual case of the user doing 10-15 iterations with different squibs, e.g., exploring different time periods with the same instructions, the user will receive one page for each effort, all of the pages becomes tabs in the one Excel workbook.

Table 5 shows one set of summarization, aptly summarized ‘Ideas’. The three summarization are key ideas, themes, and then perspectives.

Table 5: Summarization of the output from SCAS in terms of key ideas, themes emerging from the key ideas, and then a discussion of the positives and negatives of each theme.

Key ideas simply highlights what the term suggests, namely what are the ideas presented to the user. This study generates a great number of key ideas because input to the studies comprises the basic questions and the answers pertaining only to the 21st Century both shown in Table 4.

Themes further summarize the key ideas, this time using SCAS to group together the related group of key ideas, perspectives, in turn, take these themes and provide the basis for ongoing discussion and learning, showing two alternative points of view for each theme.

The ’Human Reaction’ to These Ideas, as Envisioned by SCAS

As part of the summarization, SCAS returns with three different analyses of the sets of ideas. The analyses look at populations of people, whether these populations be defined by who they are (for both interested and opposing audiences), or by the way they think (alternative viewpoints). Table 6 shows the various groups and their reactions to the ideas uncovered by SCAS. It is important to keep in mind that these reactions are to the general ideas, not to any specific idea.

Table 6: The ‘human’ reaction to these ideas as envision by SCAS

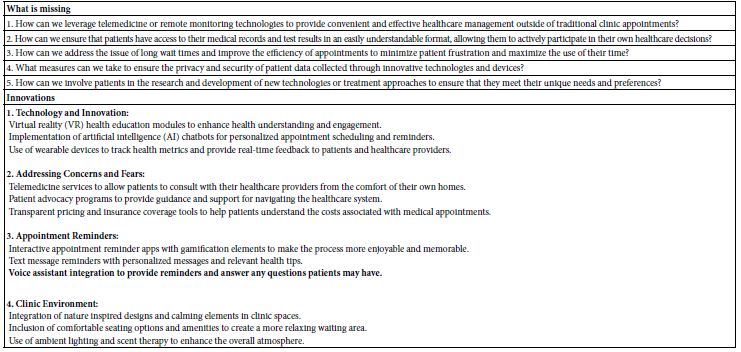

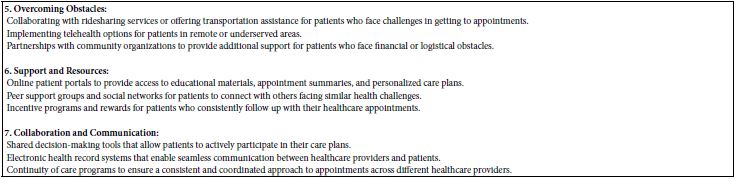

The final analysis deals with SCAS as an inventor. Table 7 shows two sections. The first section lists questions about what may be missing. These are typically questions which ask: How do we… ? The second section lists possible innovations, based upon the information processed by SCAS. The list of possible innovations is organized by topic.

Table 7: Using SCAS to suggest new products and services

Discussion and Conclusions

This paper emerged from recurring discussions about the real problem of ‘no shows’ in the world of medicine. The problem is a vexing one, perhaps growing because of the increasing difficulties encountered in the practice of medicine. One problem is the growing lack of affordability of medical treatments, the cost perhaps acting as a mechanism to discourage visits because of the fear of incurring expenses that are unaffordable to the patient. A second problem is the reality that doctors no longer make house calls. The patient must go to the doctor, a trip which might be difficult to schedule in view of the competing demands on the patient’s time. The third is the loss of the personal relationship between patient and doctor as the small, perhaps long-time practices are incorporated into the large medical practices. What was a personal relationship between patient and doctor (or other medical professional) now becomes a short interaction, often with the doctor’s assistant taking the necessary measurements, and the doctor meeting the patient for a few minutes debrief [8].

The importance of this paper is not in the solution in provides, but rather in the way SCAS can help focus the problem, providing a source of ideas. The speed (minutes), the extensive results in terms of the ‘human element’, and the presentation of the results in an easy-to-understand format, all suggest that those in the medical profession might avail themselves of SCAS as they enter a new subject area, if only to understand some of the issues from the part of the patient, the doctor, and the system. Scattered publication suggested only the positive, the ‘up-side’, and not the down-side of using AI and such offshoots as SCAS to solve the problem of no-shows [9].

A second aspect of the approach presented here comes from the potential of instructing SCAS to ‘imagine’ what will happen in the years to come, or even to imagine what things were like a century ago or even longer. By simply asking SCAS to assume that all the topics are to be asked from the framework of the year 2200, almost 75 years into the future, it is possible to jump-start futuristic thinking. There is no reason to assume that the answers will be ‘correct.’ On the other hand, to SCAS there is no penalty for being ‘wrong’, so that SCAS dutifully produces its best guess, once it has been properly instructed. It is that potential to focus on the future in terms of concrete questions and suggestions which make the approach attractive, especially in light of the simplicity of executing just another ‘iteration,’ albeit this time priming SCAS to guess about the future or guess about the past [10,11].

References

- Parsons J, Bryce C, Atherton H (2021) Which patients miss appointments with general practice and the reasons why: a systematic review. British Journal of General Practice 71(707): e406-e412. [crossref]

- Nadarzynski T, Miles O, Cowie A, Ridge D (2019) Acceptability of artificial intelligence (AI)-led chatbot services in healthcare: A mixed-methods study. DIGITAL HEALTH.v.5. [crossref]

- Kreps GL, Neuhauser L (2013) Artificial intelligence and immediacy: designing health communication to personally engage consumers and providers. Patient Education And Counseling 92: 205-10. [crossref]

- Lacy NL, Paulman A, Reuter MD, Lovejoy B (2004) Why we don’t come: patient perceptions on no-shows. The Annals of Family Medicine 2: 541-545. [crossref]

- Miller AJ, Chae E, Peterson E, Ko AB (2015) Predictors of repeated “no-showing” to clinic appointments Am J Otolaryngol 36: 411-4. [crossref]

- Sun CA, Taylor K, Levin S, Renda SM, Han HR (2021) Factors associated with missed appointments by adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: a systematic review. BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care 9(1).

- Wu T, He S, Liu J, Sun S, Liu, K,et al.( 2023) A brief overview of ChatGPT: The history, status quo and potential future development. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 10: 1122-1136.

- Bjerring JC, Busch, J (2021) Artificial intelligence and patient-centered decision-making. Philosophy & Technology 34: 349-371.

- Yun JH, Lee EJ, Kim DH (2021) Behavioral and neural evidence on consumer responses to human doctors and medical artificial intelligence. Psychology & Marketing 38: 610-625.

- Fogel AL, Kvedar JC (2018) Artificial intelligence powers digital medicine. npj Digital Med 1: 5. [crossref]

- Kuper A, Whitehead C, Hodges BD (2013) Looking back to move forward: using history, discourse and text in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 73. Medical Teacher 35: e849-60. [crossref]