DOI: 10.31038/CST.2024912

Abstract

The study shows what can be done when AI is built into a platform that is easy to use, with the topic being how the surgeon should communicate with a person who is about to have an operation for cancer. The approach posits three mind-sets for each type of cancer patient. Embedded AI in the program (SCAS; Socrates as a Service) is then instructed to answer a set of seven standard questions for each of the three AI-suggested mind-sets for that specific cancer. The study shows the power of AI to simulate the interaction between surgeon and patient, with the approach showing promise as an easy-to-customize method for teaching how to become sensitive to the emotional needs of people.

Introduction

Communicating with patients is a crucial aspect of a surgeon’s role, helping build trust and alleviate any fears or concerns the patient may have. Patients want to know about the risks and benefits of the surgery, as well as alternative treatment options available. It is important for the surgeon to explain the procedure in a way that the patient can understand, using non-medical jargon and providing visual aids if necessary. Patients also want to know about the recovery process, including how long it will take and what restrictions they may have post-op. Additionally, patients appreciate surgeons who are upfront about the potential complications of the surgery, as this shows transparency and honesty. It is important for the surgeon to listen to the patient’s concerns and address them in a compassionate and empathetic manner. Patients want to feel like their surgeon cares about their well-being and is invested in their successful outcome. Providing emotional support during the pre-op and post-op period can go a long way in helping the patient feel more at ease. Surgeons should also take the time to explain the anesthesia process to patients, as this can be a source of anxiety for many. Patients want to know what to expect during the surgery and how they will be monitored throughout the procedure. It is important for the surgeon to reassure the patient that they will be well cared for and that their safety is the top priority. Empathy and active listening are key components of effective communication with patients.. Furthermore, patients appreciate it when surgeons involve them in the decision-making process and take their preferences into account. This can help empower the patient and make them feel more in control of their healthcare. Surgeons should encourage patients to ask questions and express any concerns they may have, creating an open and transparent dialogue. A well-informed patient is more likely to have a positive outcome and adhere to post-operative instructions. Thus, effective communication between surgeons and patients is essential to build trust, alleviate fears, and ensure a successful surgical outcome. By addressing the patient’s concerns, providing clear and concise information, and showing empathy and compassion, surgeons can establish a strong rapport with their patients. To summarize, a well-informed patient is a confident patient, and a confident patient is more likely to have a positive surgical experience [1-4].

The Contribution of Mind Genomics to Understanding People, and In Turn Communicating with Patients

The field of mind genomics tries to explain how and why people act and make choices. It uses psychology, neuroscience, and marketing research to find out what people’s unconscious thoughts are that make them make the choices and preferences they do. Mind Genomics can separate people into groups based on the way they think by using advanced data analysis methods [5-7]. One of the most important things that Mind Genomics has shown is that people have different mental models. Within these mindsets are specific ways of thinking that affect how people see the world, decide what to do, and form opinions. Researchers can make products, services, and interventions that better meet the needs and preferences of different groups of people by finding and understanding these modes of thought. It’s possible that this personalized approach will make customers happier, help patients do better, and help the business grow [8,9]. The implications of discovering mind-sets extend far beyond the realm of marketing and consumer behavior. Within the medical field, knowing how patients think and feel can help create more effective treatment plans that make patients happier and improve their health. By making healthcare interventions fit the way patients think, providers can get patients to follow through more often, get them more involved, and ultimately improve the quality of care overall. If this personalized approach works, it could completely change how healthcare is provided and experienced [10-12]. Mind Genomics can help doctors and nurses better understand their patients’ unique behaviors and thoughts in clinics and hospitals. Finding the thought patterns that cause patients to act out can help doctors come up with better ways to talk to them, treat them, and help them in other ways. This individualized approach can help patients and providers trust each other more, work together better, and have a better relationship. Healthcare professionals can make a more supportive and empowering care environment for patients by recognizing and respecting their unique mental states [13-15]. In order to help patients in the clinic and hospital, healthcare professionals must first understand that people have different mental states. Clinical professionals can better meet the needs and preferences of each patient by recognizing and understanding the unique ways that each person thinks and acts. This personalized approach can help doctors and nurses get to know their patients, earn their trust, and provide better care overall. Health care professionals can make care more patient-centered and interesting by using Mind Genomics principles [16-19]. Mind Genomics’ discovery of mindsets could change the way healthcare is provided and experienced in a big way. Healthcare providers can improve outcomes, make patients happier, and lead to better health results by understanding and adapting interventions to each patient’s unique cognitive patterns. This personalized approach has the potential to change the relationship between the patient and the provider, get the patient more involved, and ultimately improve the quality of care as a whole. Healthcare professionals can make the care environment more caring, supportive, and effective by recognizing and embracing the different ways people think. To sum up, Mind Genomics is a revolutionary way to study how people act and make choices [20]. Researchers can make interventions, products, and services better fit the needs and wants of different groups of people by figuring out the different ways people think. The discovery of mindsets has huge implications for medicine, because tailoring care to each patient’s unique ways of thinking can lead to better outcomes, higher patient engagement, and higher patient satisfaction. Healthcare professionals can make care more compassionate and patient-centered by using Mind Genomics principles in their work. This can lead to more collaboration, trust, and better health outcomes..

How can AI Help Mind Genomics Discover Mind-Sets

Mind Genomics and AI can work together to learn about mindsets by combining them through data analysis and pattern recognition. AI can find patterns and themes that are unique to each mind-set by gathering and analyzing data from people with those mindsets. Because of this method, the AI can give each mindset a name or label based on the most important traits found in the data. This process of giving people names helps to group and tell the difference between different ways of thinking, which makes it possible to use more targeted and personalized communication methods. AI can not only name the mindset, but also guess what kinds of people are in it by looking at things like age, gender, and socioeconomic status. AI can find trends and correlations in the data collected from people with similar mental states. These can help us understand the demographic profile of each mental state. This information can be used to make sure that communication and intervention strategies work better with people who are in a certain demographic group and have a certain mindset. When trying to guess what questions a cancer patient might have before surgery, AI can use what it knows about different mindsets to guess the most common worries and doubts that people with that mindset might have. AI can find common themes and topics that are usually talked about before surgery by looking at data from past interactions between surgeons and cancer patients. This ability to predict the future lets AI know ahead of time what questions and concerns are most likely to come up during pre-operation consultations and prepares to answer them. If everything goes well with the surgery, AI can use what it knows about how people think to send the patient personalized and caring messages. AI can figure out the best ways to share good news with people of different personalities by looking at data on successful outcomes and patient feedback. This personalized way of talking to the patient helps to build trust and a relationship with them, which makes the recovery process more positive and helpful. If, on the other hand, things don’t go as planned and problems arise, AI can use its knowledge of how people think to send the patient messages that are both kind and helpful. AI can figure out the best and most understanding ways to share difficult information with people of all mentalities by looking at data on failed outcomes and patient experiences. This personalized way of talking to the patient helps to manage their expectations and support them during a tough and uncertain time.

Putting AI to the Test

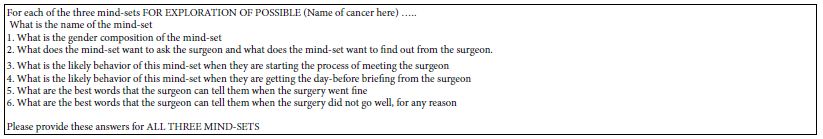

The original Mind Genomics approach was to require the user to state the problem and provide four questions which tell a story. To each question the user would be requested to provide four answers, the answers called ‘elements,’ and being stand-alone phrases which conveyed a single idea. While seeming straightforward to an experience user, the ‘task’ of providing questions, and then answers to the questions soon emerged as a roadblock. The consequence was that many prospective users ‘froze; at the prospect of asking and answering questions, with the statement that they were not sufficiently conversant with the topic. The sad outcome was that many prospective users aborted their efforts as soon as they were requested to participate. The solution to the problems emerged from the introduction of Chat GPT by Open AI, Inc. The user simply had to ask the AI about the topic, and the AI would return a paragraph or two, from which the user would create the four questions. Later on, the system to create questions was codified into SCAS (Socrates as a Service). The strategy was to create 15 questions for each input ‘squib’ or background statement about the problem. The user was able to select questions, edit them if desired, provide their own questions if desired, and then ‘drop the questions’ into the study. Once the four questions were selected after one or several iterations, the user would then move to the next section, where the ‘squib’ was the question previously selected. The process would return 15 answers to each question. The entire process allowed for iteration after iteration, each iteration taking 10-15 seconds. The ‘hard part’ evolved to editing and polishing the squib to introduce the topic, the questions that were selected so that they would generate the correct answers, and finally the answers so that they would be meaningful as well as simple. What took days and weeks now took less than an hour and required relatively little familiarity with the topic. The fortunate ‘byway’ leading to this project on communication between surgeon and patient before the cancer operation occurred when the ‘squib’ to introduce the project was expanded, so that the squib contained within it statements to the effect that there were a certain number of (not-yet-named) mind-sets, and the answers to certain questions had to be created by AI once the mind-sets were established, also by AI. Table 1 shows the ‘squib’ or orientation to AI. The same squib was used for each of the nine cancers ‘studied’ using AI to provide the answers. Each table will present the three mind-sets for the particular cancer. It is important to keep in mind that the AI does not keep the information generated. Rather, each iteration is separate. The answers provided by AI attempt to conform to the format prescribed in Tables 1-9.

Table 1: Most of the time the answers do fall into the format. Occasionally, the introductory words might change, but the answer itself is appropriate to the question.

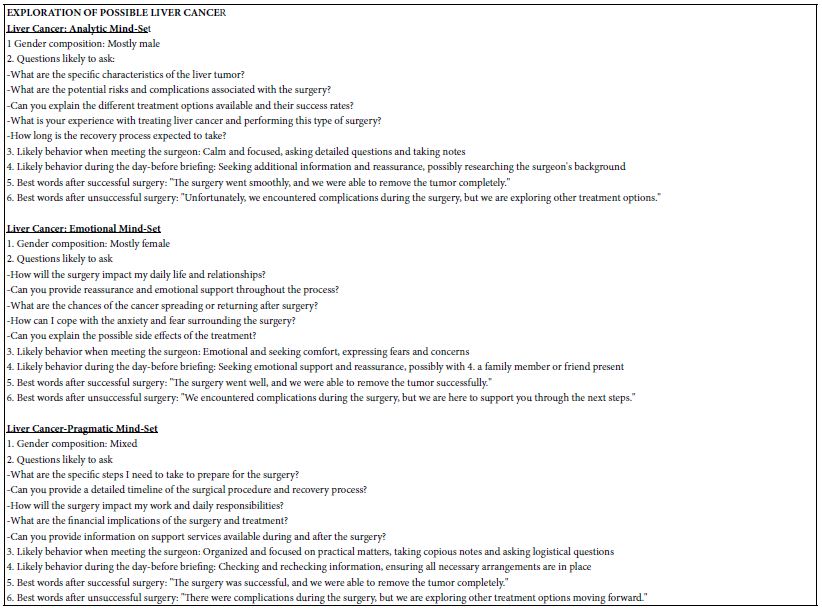

Table 2: AI exploration of three mind-sets for liver cancer

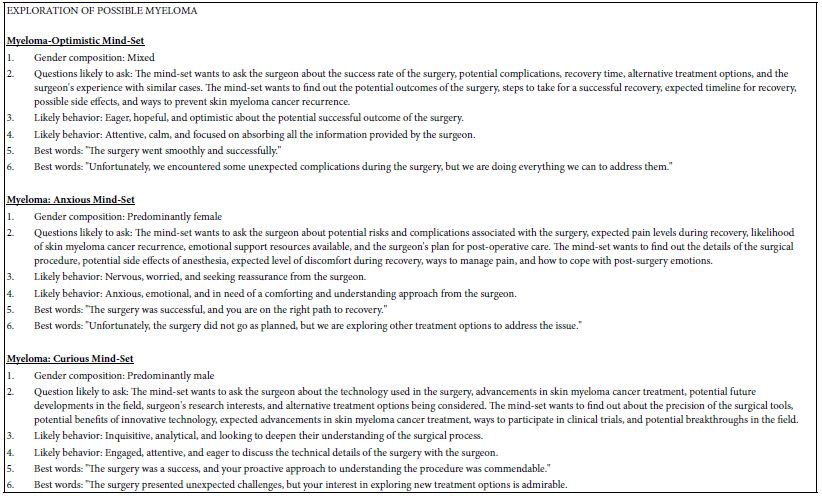

Table 3: AI exploration of three mind-sets for Myeloma

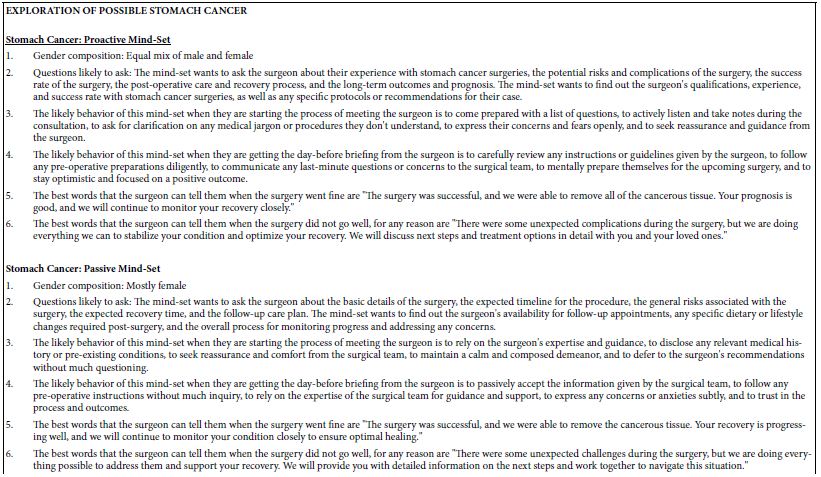

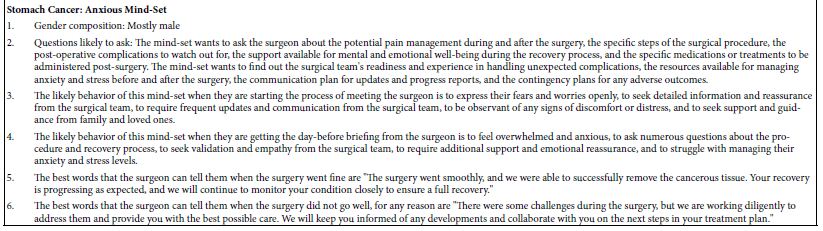

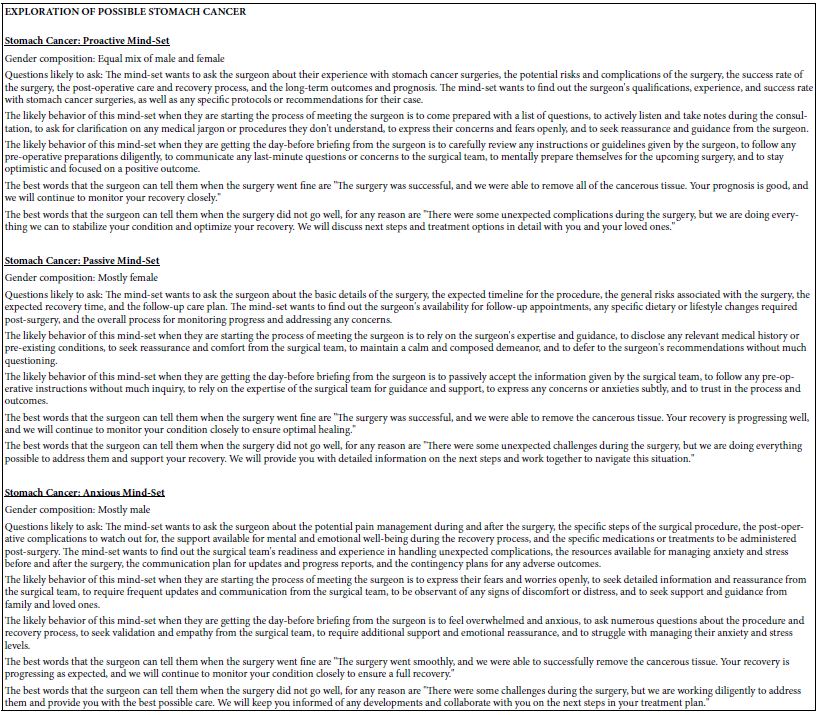

Table 4: AI exploration of three mind-sets for stomach cancer

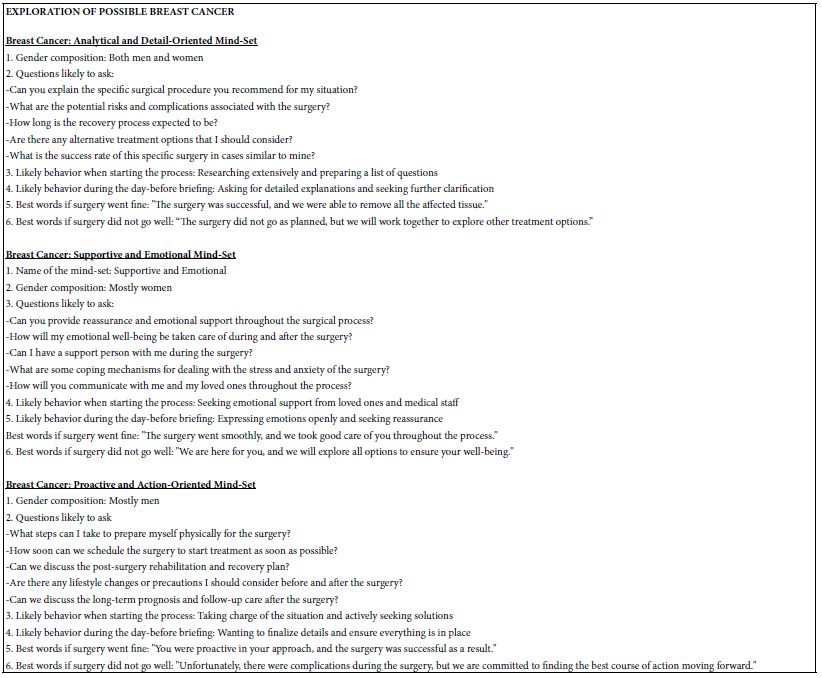

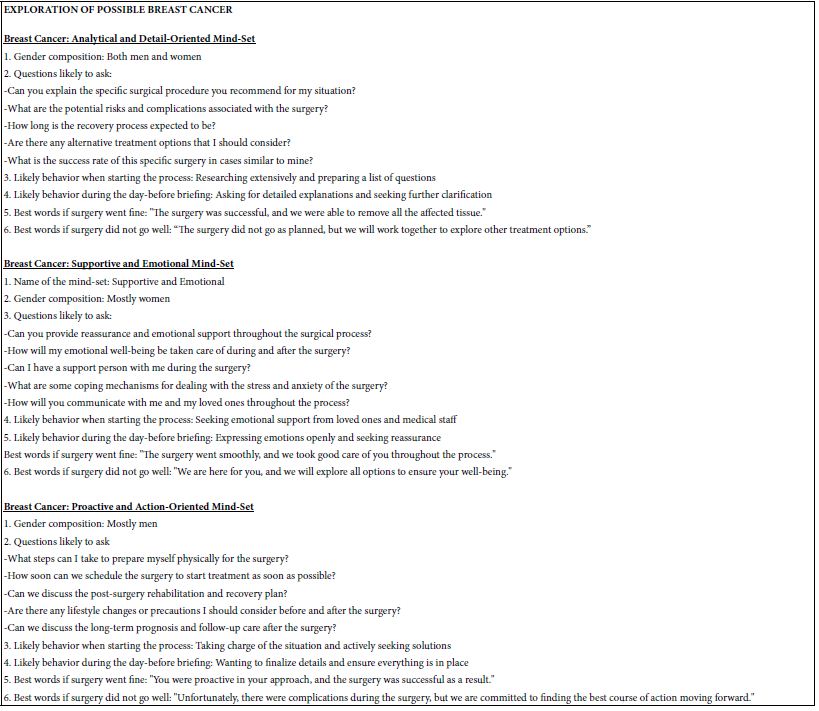

Table 5: AI exploration of three mind-sets for breast cancer

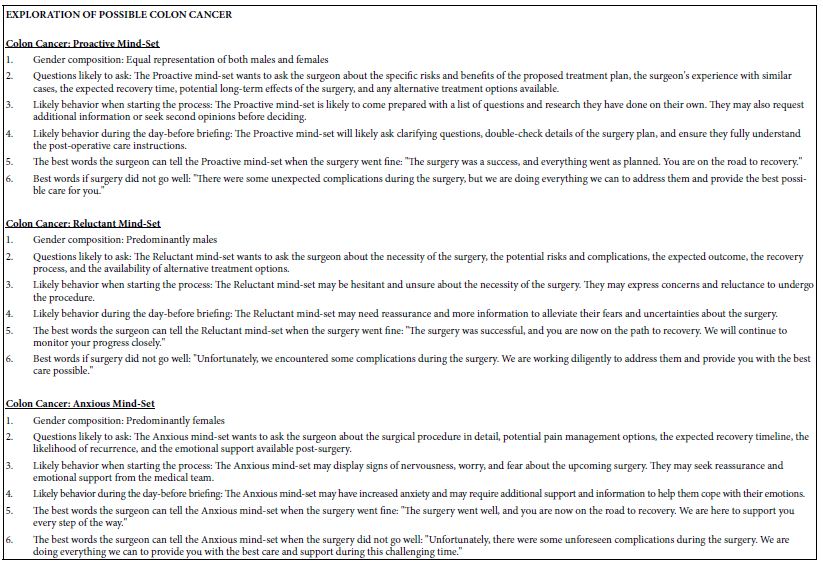

Table 6: AI exploration of three mind-sets for colon cancer

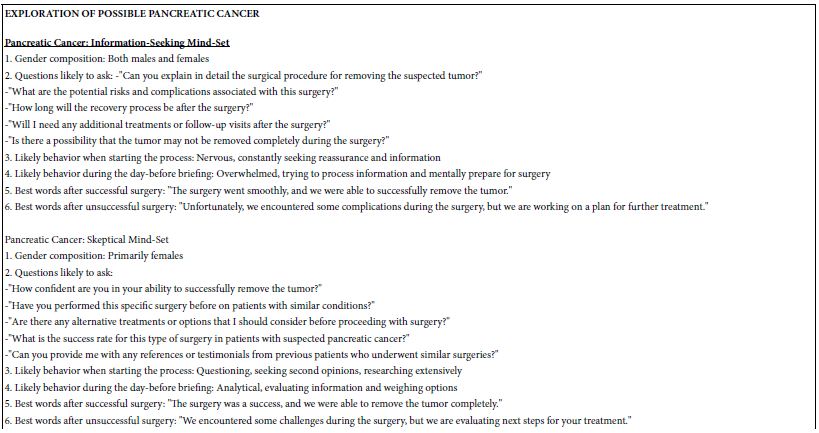

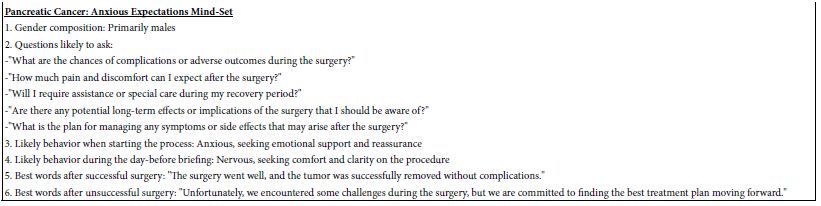

Table 7: AI exploration of three mind-sets for pancreatic cancer

Table 8: AI exploration of three mind-sets for stomach cancer

Table 9: AI exploration of three mind-sets for breast cancer

Dealing with Different Results from AI-Implications, Problems, Hidden Benefits

When artificial intelligence generates various synthesized mindsets for a patient with lung cancer, it can be both a problem and a learning opportunity. The different mindsets could be the result of AI processing and interpreting information in different ways, leading to contradictory conclusions. This discrepancy can be confusing for healthcare providers, making it difficult to determine the best course of action for the patient. However, the presence of various mindsets can be viewed as a positive aspect of using AI in healthcare education. It enables a more thorough examination of various perspectives and approaches to patient care, potentially improving nurses’ and doctors’ knowledge and skills. By examining and considering various synthesized mindsets, healthcare providers can gain a better understanding of the complexities involved in treating lung cancer patients. When using AI to teach nurses and doctors, encountering different mindsets for a patient with lung cancer emphasizes the value of critical thinking and evidence-based practice. It emphasizes the importance of healthcare providers critically evaluating AI-generated information and considering multiple perspectives when making clinical decisions. It also emphasizes the importance of continuing education and training to stay current on the latest advancements in healthcare technology and AI algorithms. Overall, the presence of various synthesized mindsets in AI-generated recommendations for patient care serves as a reminder that healthcare is a dynamic and ever-changing industry. It requires healthcare providers to think critically, be adaptable, and constantly seek new knowledge and insights in order to (Table 10).

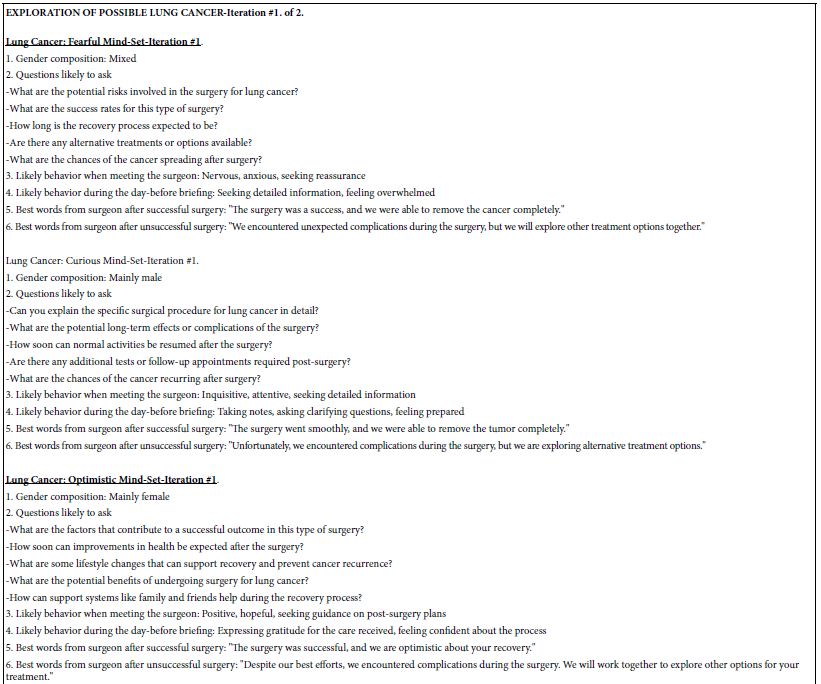

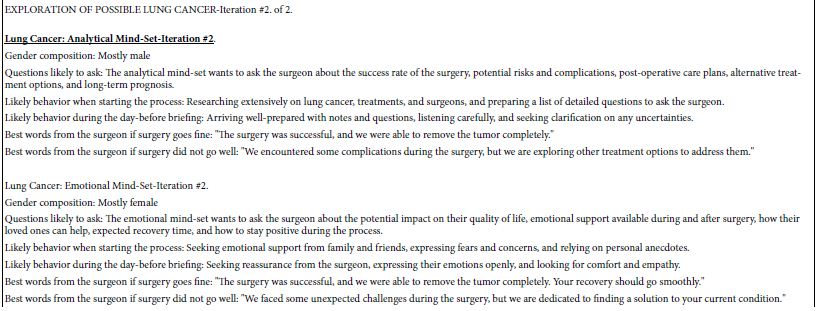

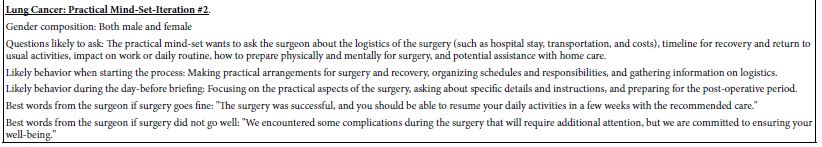

Table 10: AI exploration of two iterations to create three mind-sets for lung cancer

Questions Posed by AI in the Output Stated as Facts, and Elaboration by AIs

The standard output of SCAS (Socrates as a Service) comprises both questions/answers as well as additional questions that should be answered. These are questions generated for every iteration, no matter what the input. That is, SCAS ends up creating additional ‘questions for further thought and study.’ Here the questions are, put to AI as statements of ‘fact,’ and with a request to AI to elaborate on the ‘fact’ (Table 11).

Table 11: Additional ‘insights’ provided by AI as elaborations of information put to AI as ‘facts’

Discussion and Conclusions

AI synthesis of patients’ thoughts before surgery has the potential to completely change the medical field by giving personalized insights and suggestions based on patient data. With this technology, surgeons can better understand their patients’ feelings, hopes, and fears, which leads to better communication and better surgical outcomes. AI can also help doctors understand the psychological aspects of surgery by making them smarter and more empathetic. AI synthesis can be used to find possible risks and complications before surgery. This can lead to better results and happier patients. There could be problems with relying only on AI to combine mindsets. It’s possible that the algorithms used don’t always understand how complicated human emotions and experiences are, which could lead to assessments that are too simple or wrong. Additionally, relying too much on AI in medical practice may take the place of human connection and empathy, which could make the relationship between the patient and surgeon less human. In addition, using AI in this way might make intuition and personal judgment less important when making medical decisions, which could stop medical professionals from developing these important skills. However, AI for mindset synthesis in medicine may have advanced significantly in ten years. New technologies and algorithms may help surgeons understand and interpret patient emotions more accurately and nuancedly. AI mind-set synthesis could transform patient care and decision-making in healthcare in the next decade. AI may become part of preoperative assessments and treatment planning as technology advances, providing more personalized and efficient care. However, a renewed emphasis on human intuition and compassion in patient care may counteract AI’s overuse in medicine. Medicine may also face ethical issues related to AI use in sensitive medical settings, including privacy, consent, and technology limits. To ensure AI algorithms complement medical judgment and expertise, they must be constantly evaluated and refined. At the end of the day, the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in decision-making must be balanced with the need to provide patients with individualized attention. Over-reliance on AI synthesis could impede medical professionals’ ability to develop intuition and empathy. Care quality and patient outcomes could be jeopardized if patients and healthcare providers become emotionally distant due to an over-reliance on AI.

References

- Ertürk EB, Ünlü H (2018) Effects of pre-operative individualized education on anxiety and pain severity in patients following open-heart surgery. International Journal of Health Sciences 12: 26. [crossref]

- Grocott MPW, Ball JAS (2000) Consensus meeting: management of the high-risk surgical patient. Clinical Intensive Care 11: 263-281.

- Phillips J, Perriman C (2016) Pre-operative and post-operative care. Clinical Skills for Nursing Practice 423-446.

- Zeynep T, Gozde TS, Ikbal C, Emel S (2020) Pre-operative comfort levels of patients undergoing surgical intervention. International Journal of Caring Science 13: 1339-1345.

- Buss DM (ed.) (2005) The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology. John Wiley & Sons.

- Milutinovic V, Salom J (2016) Mind Genomics: A Guide to Data-Driven Marketing Strategy. Springer.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A Beckley J, Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind Genomics. Journal of Sensory Studies 21: 266-307.

- Prahalad CK, Ramaswamy V (2000) Co-opting customer competence. Harvard Business Review 78: 79-90.

- Swift RS (2001) Accelerating customer relationships: Using CRM and relationship technologies. Prentice Hall Professional.

- Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E, Fancott C, Bhatia P, Casalino S, Onate K, Denis JL, Pomey MP, et al. (2018) Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implementation Science 13: 1-22.

- Koh HK, Brach C, Harris LM, Parchman ML (2013) A proposed ‘health literate care model’ would constitute a systems approach to improving patients’ engagement in care. Health Affairs 32: 357-367. [crossref]

- Zapka JG, Lemon SC (2004) Interventions for patients, providers, and health care organizations. Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society 101: 1165-1187.

- Castro EM, Van Regenmortel T, Vanhaecht K, Sermeus W, Van Hecke A (2016) Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: A concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient education and counseling 99: 1923-1939. [crossref]

- Holmström I, Röing M (2010) The relation between patient-centeredness and patient empowerment: a discussion on concepts. Patient Education and Counseling 79: 167-172.[crossref]

- Spence Laschinger HK, Gilbert S, Smith LM, Leslie K (2010) Towards a comprehensive theory of nurse/patient empowerment: applying Kanter’s empowerment theory to patient care. Journal of Nursing Management 18: 4-13. [crossref]

- Benner PE, Hooper-Kyriakidis PL, Stannard D (2011) Clinical wisdom and interventions in acute and critical care: A thinking-in-action approach. Springer Publishing Company.

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T (1999) Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Social Science & Medicine 49: 651-661. [crossref]

- Gafni A, Charles C, Whelan T (1998) The physician-patient encounter: The physician as a perfect agent for the patient versus the informed treatment decision-making model. Social Science & Medicine 47: 347-354. [crossref]

- Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan S, Daley J, Delbanco TL (2002) Through the Patient’s Eyes: Understanding and Promoting Patient-Centered Care. John Wiley & Sons.

- Wallace LM (1986) Communication variables in the design of pre-surgical preparatory information. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 25: 111-118. [crossref]