DOI: 10.31038/ALE.2024114

Abstract

The paper introduces the use of AI coupled with Mind Genomics technology (BimiLeap.com) to understand the topic of how countries think about the U.S.’ position on nuclear deterrence. The entire exercise is done using AI (ChatGPT 3.5), with the BimiLeap.com platform. The five sections cover a broad range of aspects for the topic, and are set up to be rapid, cost effective, easy to do, and in some respects, virtually automatic. The results presented in this paper required approximately six hours to generate, including the initial and secondary AI analyses. The range of aspects goes from simulated “listening to enemy strategy meetings” to key emerging ideas, and onto AI-suggested innovations, expected responses by different audiences, and finally suggested questions and both optimistic and pessimistic answers. The paper is presented as an approach, with the topics easy to change, and the scalability straightforward to demonstrate.

Keywords

AI-generated simulations, Mind Genomics, Nuclear deterrence, Strategic signaling

Introduction

The U.S.’ nuclear arsenal is a crucial part of its strategic defense, but its lack of open threat to nations has led to aggressive postures. To revise defense signals without compromising global stability or reputation, U.S. policymakers must evolve strategic signaling, including bolstering military presence, conducting high-profile exercises, and issuing diplomatic statements. Monitoring hostile nations’ rhetoric and consistent communication of “red lines” is crucial for effective nuclear deterrence. AI simulation and Mind Genomics thinking offer a powerful tool to understand high-level strategic discussions in the minds of nation-states. AI simulation platforms can analyze geopolitical data and simulate decision- making processes based on historical patterns, key events, and diplomatic or military postures. Mind Genomics, the study of how individuals or groups structure their thinking and interpret the world, can codify the thought processes of leaders and policymakers. By merging these technologies, the U.S. can simulate different nations’ responses to various U.S. actions, such as bolstering military presence, conducting strategic exercises, or issuing diplomatic statements [1,2]. This approach can break down a nation’s strategic rationale into cognitive and cultural predispositions, enabling more accurate forecasts of a nation’s response to U.S. policy changes [3,4]. It can also function as a form of strategic empathy, enabling the U.S. to craft tailored policies.

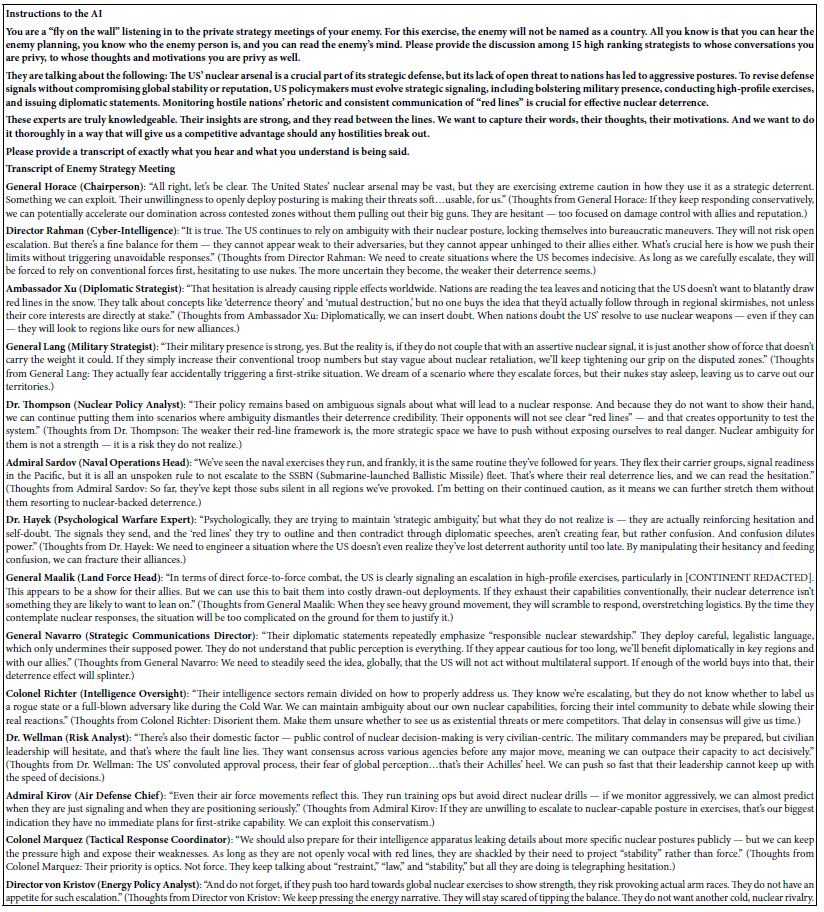

Phase 1: Simulating Private Strategy Discussions Among Opponents of the USA

AI-driven simulations of enemy conversations can provide valuable insights into American policy and strategy development (Table 1). By role-playing the enemy’s perspective, AI can anticipate potential threats and understand weaknesses in American policies [2]. This predictive insight can mitigate risks and enhance national defense mechanisms [5]. AI simulations can also expose blind spots within current strategic thinking, revealing perspectives that American strategists may not see naturally. This effort can fuel defensive preparedness and negotiation tactics [6]. AI simulations can compress time and offer predictive outcomes based on potential decisions, allowing agencies to respond in real-time to threats while staying ahead of competitors [7,8]. However, there are risks and limitations to AI-assisted simulations. One issue is over-reliance on technology and algorithms instead of human judgment and intuition. AI algorithms may not have human motivations, emotions, or spontaneity, leading to irrational or emotional decisions. Additionally, AI simulations may not reflect real discussions due to human factors. Despite these limitations, AI-assisted simulations can enhance understanding, decision-making speed, and avoid blind spots.

Table 1: AI simulation of an overheard “enemy” discussion about American nuclear policy.

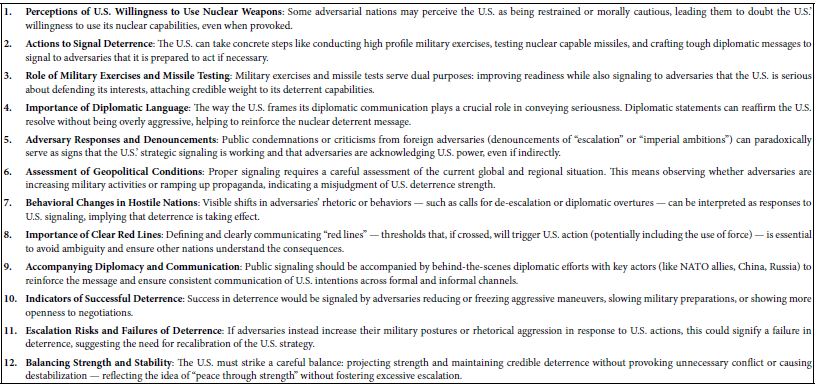

Phase 2: Key Ideas Emerging

The key ideas in the topic questions revolve around the concept of U.S. nuclear deterrence and strategic signaling — focusing on how the United States can communicate its readiness to use military force, including nuclear weapons, to deter adversaries without explicitly threatening them [9-12]. These key ideas emphasize the delicate balance the United States must maintain in its nuclear deterrence strategy, combining visible military strength with subtle diplomatic moves to ensure that its adversaries perceive its willingness to defend its interests while avoiding global instability. Table 2 shows 12 key ideas emerging from the simulation present in Table 1 and a subsequent AI- based analysis by the Mind Genomics platform, BimiLeap.com.

Table 2: Key ideas emerging from the AI simulation of an enemy strategy meeting, and then a second and further AI analysis. The analyses were done by the Mind Genomics platform, BimiLeap.com.

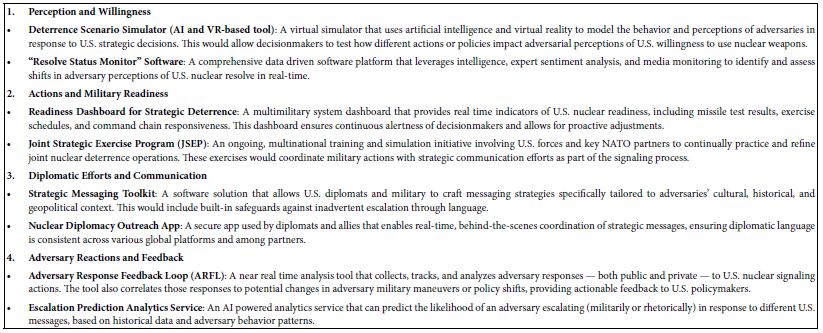

Phase 3: Innovations in Products and Services

The themes associated with U.S. nuclear deterrence and strategic signaling offer several conceptual frameworks for developing new products, services, or experiences [13-15]. Table 3 presents products and services suggested by AI, based upon the material presented in Tables 1 and 2. The AI further evaluated the information in both Tables, and generated the suggestions in Table 3.

Table 3: Innovation in products and services, suggested by AI, and based upon the information shown in Tables 1 and 2.

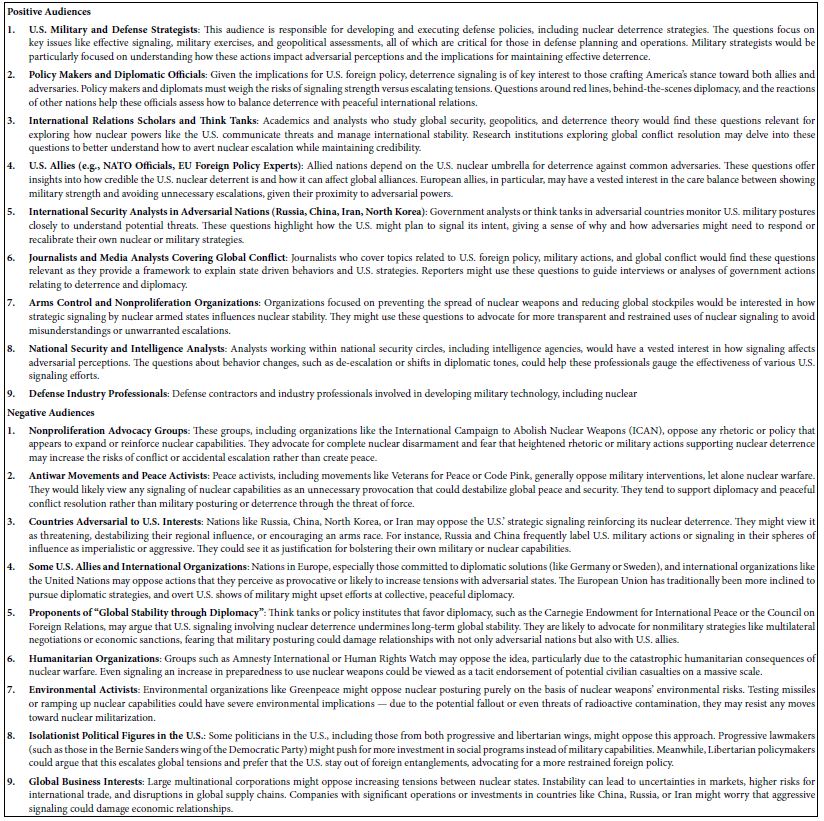

Phase 4: The Different Players (Positive Versus Negative Audiences)

Several distinct audiences would have a strong interest in the topic questions, each bringing a unique perspective based on their professional, academic, or geopolitical involvements [16-18]. These audiences are shown in Table 4 and comprise both those who are “interested” and those who are not interested, viz., possibly “hostile.” Once again, the analysis was done after the fact, in a second pass through the data to provide more insight by AI.

Table 4: Positive and negative audiences.

Phase 5: AI-Generated Questions and Answers for Further Thought

The AI was presented with the situation presented in Table 2. The AI was instructed to create questions, and then give both an optimistic answer and a pessimistic answer to the same question. Table 5 shows the results. The benefit here is that the AI can generate a great number of questions in a short time and provide answers [4,19-21].

Table 5: AI generated questions and two answers for each question; optimistic versus pessimistic, respectively.

Discussion and Conclusions

AI combined with Mind Genomics works as a safe testing ground where various communication scenarios — words, actions, or threats— can be “played forward” to understand precisely how they may backfire, escalate tensions, or bring about desired mediations. Such tools would also enable the U.S. to make faster, informed decisions in unprecedented crises, whether arising from smaller rogue nations or larger superpowers. By anticipating hostile rhetoric, understanding a nation’s internal political conditions, and knowing exactly where the “red lines” fall, AI simulations can precisely calculate the tipping point at which a country might enter an irreversible aggressive stance. Thus, this system works like a blueprint for creating not only stronger deterrence policies but also more effective diplomatic resolutions. Finally, the long-term potential of these simulations lies in their ability to integrate into international consensus-building. For deterrence to be effective, it must not only be unilateral but shared among allies. This enhanced AI and Mind Genomics model could be a framework that multiple democratic governments employ to analyze the decisions of shared adversaries. In doing so, the U.S. would gain not only tactical advantages but help contribute to a shared platform of predictive thinking, ensuring stability and global peace.

Based upon the AI exercise reported here, the key ideas related to U.S. nuclear deterrence and strategic signaling can be grouped into six distinct themes:

Perception and Willingness

Perceptions of U.S. Willingness to Use Nuclear Weapons. Some adversaries doubt the U.S.’ willingness to use nuclear weapons, leading to questions about the effectiveness of its deterrent posture.

Actions and Military Readiness

Actions to Signal Deterrence. The U.S. can engage in military actions such as exercises, missile testing, and tough diplomatic messaging to show its readiness and resolve. These actions not only test U.S. readiness, but they are also key components in strategic signaling to deter adversaries.

Diplomatic Efforts and Communication

Importance of Diplomatic Language. Strategic use of diplomatic language can underscore U.S. seriousness without escalating tensions. Diplomatic support of public signaling is pivotal, both with adversaries and allies, ensuring that messages are clearly communicated through multiple channels. Establishing and clearly communicating red lines helps avoid ambiguity and ensures adversaries are clear about the consequences of crossing thresholds.

Adversary Reactions and Feedback

Adversaries’ denouncements, such as accusing the U.S. of “escalation,” might paradoxically indicate that U.S. signaling is effective and being acknowledged. Visible shifts in rhetoric or behavior toward calls for diplomacy from adversaries can be viewed as signs of effective deterrence.

Geopolitical Assessment and Strategy Adjustment

Strategic signaling must be informed by constant assessments of adversarial military activities and propaganda to ensure proper messaging and deterrent force are applied. Signs of successful deterrence include adversaries scaling down aggressive maneuvers and showing a willingness to negotiate.

Failures, Escalation, and Risk Management

If adversaries respond to U.S. signaling with increased military presence or aggression, it points to a failure in deterrence, necessitating strategic recalibration. The U.S. must strike a balance between projecting sufficient strength to deter adversaries without causing unintended escalation or regional destabilization.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the ongoing help of Vanessa Marie B. Arcenas and Isabelle Porat in the preparation of this and companion manuscripts.

References

- Cox J, Williams H (2021) The Unavoidable Technology: How Artificial Intelligence Can Strengthen Nuclear The Washington Quarterly 44(1): 69-85.

- Davis PK, Bracken P (2022) Artificial intelligence for wargaming and The Journal of Defense Modeling and Simulation: Applications, Methodology, Technology.

- Horowitz M, Kania EB, Allen GC, Scharre P (2018) Strategic Competition in an Era of Artificial Center for a New American Security.

- Johnson J (2021) Deterrence in the age of artificial intelligence & autonomy: a paradigm shift in nuclear deterrence theory and practice? Defense & Security Analysis 36: 422-448.

- Goldfarb A, Lindsay JR (2022) Prediction and Judgment: Why Artificial Intelligence Increases the Importance of Humans in War. International Security 46: 7-50.

- Johnson J (2019) Artificial intelligence & future warfare: implications for international Defense & Security Analysis 35: 147-169.

- Layton P (2021) Fighting Artificial Intelligence Battles: Operational Concepts for Future AI-Enabled Joint Studies Paper Series, 4.

- Turnitsa C, Blais C, Tolk A (2022) Simulation and John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Borges AF, Laurindo FJ, Spínola MM, Gonçalves RF, et (2021) The strategic use of artificial intelligence in the digital era: Systematic literature review and future research directions. International Journal of Information Management 57: 102225.

- Flournoy MA, Lyons RP (2016) Sustaining and Enhancing the US Military’s Technology Strategic Studies Quarterly 10: 3-14.

- Morgan FE, Boudreaux B, Lohn AJ, Ashby M, et (2020) Military Applications of Artificial Intelligence: Ethical Concerns in an Uncertain World. RAND Corporation.

- Stone M, Aravopoulou E, Ekinci Y, Evans G, et (2020) Artificial intelligence (AI) in strategic marketing decision-making: a research agenda. The Bottom Line 33: 183- 200.

- Mühlroth C, Grottke M (2020) Artificial Intelligence in Innovation: How to Spot Emerging Trends and Technologies. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 99: 1-18.

- Sayler, KM (2020) Artificial Intelligence and National Security. Congressional Research Service, R45178.

- Scharre P (2023) Four Battlegrounds: Power in the Age of Artificial W.W. Norton & Company.

- Ali MB, Wood-Harper T (2022) Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a Decision-Making Tool to Control Crisis Situations. In: Ali M (ed.), Future Role of Sustainable Innovative Technologies in Crisis Management, IGI Global,. 71-83.

- Johnson J (2021) Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Warfare: The USA, China, and Strategic Manchester University Press.

- Tsotniashvili Z (2024) Silicon Tactics: Unravelling the Role of Artificial Intelligence in the Information Battlefield of the Ukraine Asian Journal of Research 9: 54-64.

- Aydin Ö, Karaarslan E (2023) Is ChatGPT Leading Generative AI? What is Beyond Expectations? Academic Platform Journal of Engineering and Smart Systems 11: 118-134.

- Ehsan U, Wintersberger P, Liao QV, Mara M, et (2021) Operationalizing Human- Centered Perspectives in Explainable AI. In: Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1-6.

- Rospigliosi P (2023) Artificial intelligence in teaching and learning: what questions should we ask of ChatGPT? Interactive Learning Environments 31: 1-3.