Abstract

Objectives: The aim of this study is to expose similarities and differences in the self-concept as well as in the illness perception of persons living alone with dementia based on their biographical background.

Methods: Twelve biographical narrative interviews with persons living alone with dementia were conducted and analyzed using the methodology of Grounded Theory (Glaser and Strauss).

Results: A model of the dementia-specific self-concept was developed which explains how persons living alone with dementia experience and cope with their disease situation. In the narratives the perception of the disease situation is primarily characterized by the persons’ relation to the self-concept rather than by dementia-specific symptoms. The extent to which a person experiences their disease as a critical life event depends on their premorbid internal and external loci of control. Depending on the use of various coping strategies the self-concept is either maintained or modified.

Discussion: The open and qualitative research approach with persons with dementia enables a first explanation towards illness perception that acknowledges the persons’ active coping abilities in the disease situation. Thereby, it largely surpasses deficit-oriented views. In order to fully exploit the potential of participatory and patient-oriented research further development of research designs specific to dementia is needed.

Keywords

Dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, self-concept, coping with disease, living alone

Introduction

A positive self-concept is central to preserving mental and physical health with changing life situations, and it is key to successful and healthy aging [1,2]. Baumeister [3] gives the following definition:

“The term self-concept refers to the totality of inferences that a person has made about himself or herself. These refer centrally to one’s personality traits and schemas, but they may also involve an understanding of one’s social roles and relationships” [3, p.698]. As such, the self-concept remains a relatively stable construct of beliefs a person has made about themselves across the lifetime [4]. In advanced age subjective health status [5], subjective age [6], and the experience of social integration [7] are among the most important aspects of the self-concept. However, being confronted with critical life events such as the loss of close relatives and social roles, or disease can threaten the stability as well as the preservation of positive beliefs about one’s self [8–10]. The way a person relates to such life events does not exclusively depend on environmental and personal resources [2], but also on the locus of control [11] as a dimension of the self-concept. According to Lazarus and Folkmann [12], relating to and appraising a critical life event leads to individual coping strategies: the problem-focused strategy (e.g. consulting a doctor), the emotion-focused strategy (e.g. distraction, denial), and appraisal-focused strategy (e.g. the strain is perceived as challenge). Similarly, using positive coping strategies (such as searching information, or emotional support during the disease) correlates with maintaining a positive self-concept [13].

In the present study dementia will be regarded as a critical life event, for it is among the most common and the most momentous diseases in advanced age [14]. According to data of the World Alzheimer Report [15] the prevalence of dementia is 1.6 million individuals in Germany (1.9% of the entire population). In industrialized countries such as Germany as many as 37% of persons with dementia live alone [16]. Reasons for this are an increasing amount of single-person households in old age and changes in family structures. Living alone may coincide with further potentially critical life events such as the loss of social contacts and roles [17,18], and it can have a negative impact on the self-concept.

To the best of our knowledge there is insufficient evidence for the impact (potentially) unfavorable factors, objective symptoms of dementia, and living alone may have on areas of the self-concept [19]. The aim of this study is to identify similarities and differences in the illness perception as well as in the self-concept of persons living alone with dementia from a sociological perspective. From a medical point of view, persons with dementia have limited abilities to be aware of and to appraise their disease (anosognosia) due to neuro-cognitive dysfunctions [20]. In this deficit- and symptom-oriented view underlying structures, relationships, mechanisms and factors may remain unnoticed. In contrast, sociological approaches to illness perception and the self-concept can uncover these aspects. Such a comprehensive understanding of experience and coping of the disease situation is a prerequisite for specific and patient-oriented care.

The following questions lead our research:

- Which relevance does dementia have for the individuals‘ biography?

- How do persons with dementia experience their potentially critical life event in the context of living alone?

- Which kind of knowledge about their self and about their biography do persons with dementia have, and how do they make recourse to this knowledge over the course of their disease?

By adopting the technique of the biographical narrative interview we pursue a research with instead of about persons with dementia. This approach answers to the call to include persons with dementia into the research process made by Alzheimer Europe in their position paper [21]. Given that illness perception [22] and the self-concept [23,24] are predominantly analyzed quantitatively, a qualitative analysis seems worthwhile. Indeed, in quantitative studies persons with dementia are directly confronted with their disease. This can lead to a refusal to participate in the study [19], or to a painful experience of the cognitive impairment during the survey [25]. In addition, if the participants do not fully understand the standardized questions, the results may be distorted [19]. On the contrary, the context of free narration offers two advantages: It allows a sensitive approach to the participants, on the one hand. On the other, it enables to capture the complexity of the participants’ subjectively construed world in a dementia-specific fashion. For example, persons with dementia often rely on non-verbal communication [26], and a qualitative analysis can include para- and non-verbal features such as posture, facial expression, and gestures in the analysis.

Method of Data Collection

The Biographical Narrative Interview

This study focuses on the biographies of the participants in order to develop an understanding for the self-concept as well as mechanisms and factors that influence the perception of the disease situation. The technique of the biographical narrative interview, following Fritz Schütze [27], was used to gather biographical material. The narrative interview requires the participants’ ability to narrate. Persons with dementia master this ability for a long time after the onset of the disease [26]. In contrast to other scientific methods to data collection, this technique acknowledges the abilities of persons with dementia, so that they are able to express themselves openly about topics that are important to them. In addition, interviewers can include their impressions of the interviewees as contextual information in the analysis.

Interview Design

Our interview design closely follows Schütze’s [27] narrative interviewing technique, which is structured into three phases. According to this technique the interview starts with an initial opening question in order to encourage the interviewees’ exploration of their main narration: “Could you tell me about your life? Starting from your birth, going on to the little child that you once were and then to everything that you have experienced after that until now. You have all the time you need; anything that is important to you is interesting to me” (closely following Hermanns 1995).1 [28].

After the initial opening question, the interviewees autonomously lay out their biography (“Stegreiferzählung”). During this phase the interviewers adopt the role of the active listener, and they consciously avoid influencing the contents of the narration. During the second phase of the conversation (the period of questioning) the interviewer poses questions on topics or events in the narrative that have remained vague, or seemed implausible. In the concluding phase the interviewers specifically ask questions on topics not mentioned in the main narration, but which are relevant with regard to the research questions [27]. The method was tested in June 2017 with two persons living alone with dementia, and it was found to be viable. It should be noted that one of the interviews deviated from the ideal structure in that questions that were meant for the concluding phase were preponed. This was necessary due to the participant’s concentration and word finding difficulties during the narrative exploration. In this case, Kruse and Schmieder’s [29] postulation that the priority of qualitative research is being open towards the research object and process rather than adhering to rigid methodological principles was followed. We adopted their integrative approach for all subsequent interviews.

Sampling

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study comprised female and male home care clients aged 65 and over living alone with medically diagnosed dementia. A further prerequisite for participating in the study was the clients’ ability to informed consent. The type of diagnosed dementia refers to both Alzheimer’s disease as well as other primary or secondary forms of dementia. In order to focus the narration on the meaning of dementia, and to control for the physical strain the interview situation may cause, persons with further chronical diseases in the acute phase were excluded from the study.

The Sampling Process

The sampling process comprised several steps: First, a quantitative survey was used to collect data on previously determined characteristics of persons living alone with dementia. A descriptive analysis of this data followed (for further information refer to Illiger et al. 2018 [16]). The data comprised sociodemographic characteristics (age and sex), the availability of social resources, and the “Pflegegrad”. The latter is the term for a ranked degree of independence that regulates the provision of benefits given by the statutory care insurance in Germany. The ranking into a “Pflegegrad” follows a standardized system in which an expert assesses a person’s degree of independence in several areas of everyday life (mobility, cognitive and communicative abilities, the individual’s organization of their everyday life, social contacts, and their ability to care for themself). The lower the person’s independence, the higher is the ranked degree (1–5). As home care in Germany is largely carried out by relatives, the availability of social resources was additionally taken into account. A client has high social resources, if at least one person from their social network assumed the care and/or organization of the client multiple times per week in addition to the professional care service. A client has medium social resources, if a person from their social network assumed such responsibilities once a week, and a client has no social resources, if such support was given less than once a week. Similar categorizations can be found in other studies on social support [30, 31] and social isolation [18]. Based on the frequency distribution of these characteristics the desired sample size would be composed of twelve participants in order to cover all variables of the criteria and to reach a gender ratio of 1 (male) to 3 (female) (table 1). The cases were included in the study in stages during data collection and data analysis according to the principles of theoretical sampling [32]. On the one hand, institutions that a person attends in their lifetime (kindergarten, school) can socialize biographies. On the other, standardization is part of a comprehensive individualization process shaped by childhood experience, forming a family, or the professional background [33]. Thus a minimal and maximal contrast between the cases of the final sample could be attained: During the iterative research process, for instance, we found that dementia was not a main subject in the first three narrations. So, the search was extended to include participants who attended dementia support groups, specifically, assuming they would be more willing to speak about their disease. For maximal contrast an interview was conducted with a person who received formal care only after a neighbor had informed psychiatric services about their precarious living situation and their lack of insight for having a disease.

Table 1. Desired sample and final sample.

|

male |

female |

|||

|

desired |

final |

desired |

final |

|

|

Age2 |

||||

|

young-old persons (65–79 years) |

1 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

|

middle-old persons (80–84 years) |

1 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

|

old-old persons (85 years and over) |

1 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

|

“Pflegegrad” |

||||

|

“Pflegegrad” 2 |

1–2 |

1 |

4–5 |

5 |

|

“Pflegegrad” 3 and 4 |

1–2 |

1 |

4–5 |

5 |

|

Social resources |

||||

|

none |

1 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

|

medium |

1 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

|

high |

1 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

|

N |

3 |

2 |

9 |

10 |

Participant Recruitment and Field Access

Field access was gained via physio therapists, legal advisors, home care services, advice centers and support groups in a major German city (for more information on the choice of the research region: Illiger et al. 2018 [16]). Additionally, the study was advertised in a newspaper, in a radio interview, as well as during a dementia event inviting persons with dementia or intermediaries to contact the researchers. They were given an information sheet to spread to persons with dementia living alone. If the latter expressed interest in the study, they were contacted over the telephone or in person.

Final Sample and Biographical Material

Between October 2017 and November 2018 43 potential participants for the study were reached. 21 out of these did not fulfil the inclusion or exclusion criteria while ten others were not available for interview for various reasons (disease, death, transfer to a health care center, hospitalization, faded interest in the study). The final sample comprises ten female and two male participants (Table 1). Ten of the one-time interviews were conducted in the participants’ homes and two were conducted in a day care facility. The length of the interviews varied between 19 and 106 minutes. The average length of an interview was 43 minutes (arithmetic mean: 49 minutes). Age2

Method of Data Analysis

The interviews were recorded digitally and were fully transcribed following Selting’s [34] transcription rules. These rules entail an accurate reproduction of the spoken material, intonation (stress) by using capital letters for syllables, as well as recording the duration of pauses (in seconds in parentheses). This way, speech deviations, the prioritization of certain topics, and pausing caused by dementia, as well as para- and non-verbal expressions could be included in the analysis. For better readability the original German sentences transcribed according to these rules will be given in the footnotes exclusively. Three interviews were conducted in the presence of a further person (legal advisor and family caregivers). Their contributions are documented in the transcripts but were not included in the analysis. The data was anonymized and pseudonymized, and it was analyzed using Grounded Theory Methodology [35] and the evaluation program MAXQDA. This procedure is closely linked to the everyday understanding of persons with dementia and is suited for discovering entirely new relationships and research phenomena. The analysis started after the first interview, and, as the sampling strategy suggests, it was essential to the preparation for the ensuing interviews. The process of analysis started with generating preliminary in-vivo codes for each line that closely reflected the data. This step was conducted in regular qualitative research meetings with other social scientists in order to ensure an inter-subject comprehensibility of the data [36]. Subsequently, axial coding was used in order to establish first relationships between categories based on the many codes yielded during the open coding phase. Our analysis of the material was guided by precise questions including conditions that may prompt a person to reflect on their self-concept, persons who played important roles in their biography, as well as consequences for the self-concept. Additionally, persons without knowledge of the subject matter from other disciplines (mathematicians, engineers, physicists) attended the meetings. This was done to keep an open mind despite the social scientists’ familiarity with pertinent theory, and to allow for differentiated point of views on the data.

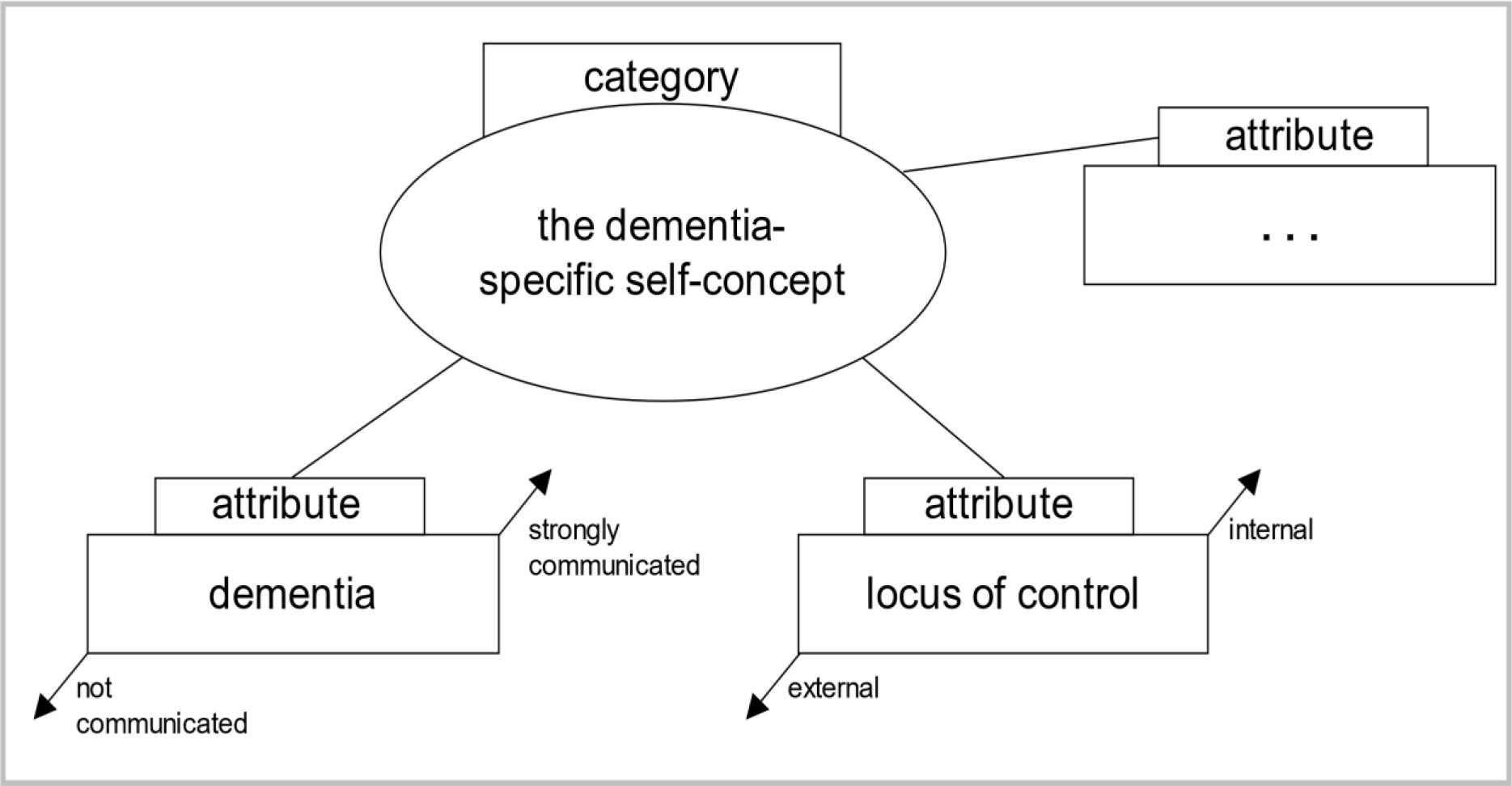

An important step in axial coding is dimensionalizing different characteristics, i.e. to compare the multiple variables of a feature. Illustration 1 exemplarily shows how characteristics are dimension-alized [38]. A core category found during the analyses was the person’s relation to the self-concept. Dementia represented one of the multiple attributes of this category. Based on the codes the participants’ statements were graphically organized along the continuum “strongly communicated” and “not communicated”. During this phase of the research process the following theoretical assumption was formulated: The greater influence a person with dementia believes to have had on passed life events (internal locus of control), the higher is their perceived control over the disease.

Illustration 1: Example for dimensionalizing specific attributes (own depiction using Böhm, Legewie, and Muhr’s (2008) theoretical schema [38]).

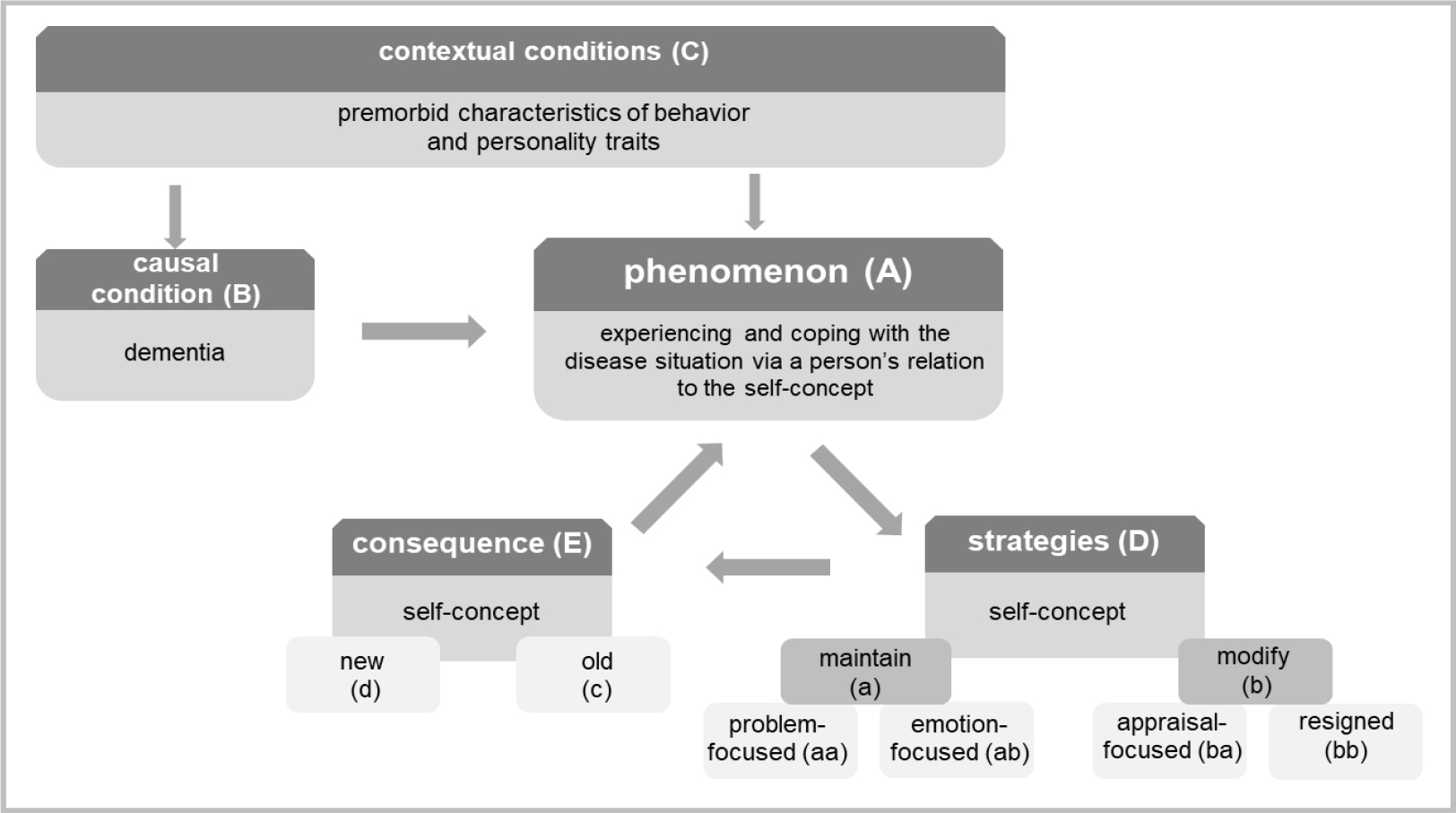

Using Strauss and Corbin’s [39] coding paradigm a foundation of relevant core categories and their relationship to one another was generated. According to Grounded Theory this foundation of core categories is composed of a central “phenomenon” (A). The data was then analyzed for “causal conditions” (B) and “contextual conditions” (C) as well as for “action strategies” (D) for the phenomenon and the resulting consequences (E). As a last step present systems of relations were re-coded and reviewed in accordance with selective coding, thus closing the theoretical coding process [40].

Results

The Model of the Dementia-Specific Self-Concept

Using the coding paradigm [39] resulted in the development of the dementia-specific self-concept model (ill. 2). The essential structure of the model will be outlined in this section while the following chapters are dedicated to the model’s several components (A-E). Dementia represents the causal condition (B) for a person’s relation to the self-concept (A). How a person reflects on the self-concept depends on a variety of contextual conditions (C). The analyses revealed that premorbid characteristics of behavior and personality traits are central categories in this context. These influenced the extent to which a person perceived dementia to take control. Taking into account contextual conditions (C) the individuals developed two different action strategies (D) in their relation to their self-concept (A): Either they maintained their self-concept (a), or they modified it (b). The adopted strategy (D) entails various consequences (E) for the self-concept of persons with dementia: Either the old self-concept is maintained (c), or a new self-concept is developed (d).

The Person’s Relation to the Self-Concept (A) in the Context of Dementia (B) – “Who am I?”

We were able to observe the person’s relation to their self-concept, i.e. the phenomenon under investigation (A) in their behavior and in their interactions. Dementia (B) causes an individual to reflect on their self-concept, i.e. the phenomenon (A) in the first place. A person with dementia is confronted with two conflicts due to their disease: The first conflict is between being self-determined and being dependent on bodily functions (e.g. limitations in everyday life caused by the disease). The second conflict is between being self-determined and being dependent on other persons (heteronomy) (e.g. relatives, health care services etc.) due to entering need for care. These conflicts trigger a discrepancy between the “old” self-concept previous to the onset of the disease and result in reflecting on the self-concept.

Illustration 2: The model of the dementia-specific self-concept based on Strauss and Corbin’s [39] coding paradigm.

Contextual conditions (C) – “Who was I?”

The biographical narrations revealed contextual conditions (C) such as premorbid characteristics of behavior and personality traits for the person’s relation to the self-concept (A). In the following, examples for this finding within the contexts of professional background and forming a family will be presented. The data reveals which roles the participants identified with before the onset of their disease (old self-concept) and whether they attributed biographical events to their own actions or rather to fate and influences by other people. The majority of women related abandoning their career after meeting their future husbands and/or due to giving birth to their first child, as becomes apparent in the following: “to what’s it called, what’s it called, to women’s technical college, which I didn’t finish, though, because at that point I knew I would marry [my husband]“ (P6:236).3 After abandoning the career path, they dedicated themselves to their role as wife and mother: “no, I couldn’t do that [continue working]. It was me who had to raise the children. and such. and prepare food and such. and clean the apartment.” (P7:274).4 Men, in contrast, saw themselves in the role of the provider: “I worked, I didn’t only provide for my family, but I provided for them very well” (P12:18).5 Often a change in the men’s career also involved a change in place: “when my husband completed his studies and got a job in X-city, I just followed him faithfully.” (P6:121).6 The number of children was also determined by the men in certain cases: “now there are two boys. He didn’t allow more, no.” (P7:173).7 Words such as “faithfully” and “allow” emphasize the experienced social dependence on the partner. However, the women’s narrations neither show any normative evaluation of their role in the relationship, nor the wish or the attempt at reaching more self-determination.

Maxims and sayings equally revealed specific characteristics of behavior or personality traits. Some considered their life to be a consequence of their own behavior: “what I did: making the best out of everything” (P9:212)8, or “I couldn’t and wouldn’t let another decide that I couldn’t stand.” (B12:24).9 Others characterized their life as fortunate or providential: “I am very satisfied with my fate, very satisfied I am.” (P11:72)10, “well, we were very fortunate.” (P9:559)11, or “must have been an angel” (P7:80).12 Analyzing context conditions (C) and action strategies (D) in the course of the disease shows how autobiographical knowledge helps persons with dementia to refer to patterns of thought and behavior that were characteristic for them in the past and how these have served them. The more influence a person with dementia believes to have had on past life events (C), the stronger their perceived control over the disease.

Action Strategies (D) – “Who do I want to be?”

Considering contextual conditions (C) in reference to a person’s relation to the self-concept (A) two action strategies (D) emerge: One consists in proactively maintaining the old self-concept (a), which results either in a problem-focused behavior (aa) (e.g. by taking helpful measures, information seeking, visits to the doctor), or in an emotion-focused behavior (ab) (redefining the disease situation, or denial of it). The second consists in modifying (b) the old self-concept, resulting in either an appraisal-focused strategy by accepting the loss of certain aspects of the self-concept (ba), or passively by expressing resignation or frustration (bb). In the following, the two strategies (a, b) with their various components (problem-focused/ emotion-focused and appraisal-focused/ resigned) when coping with dementia will be presented. The strategies were gained inductively by analyzing the interview data. The analysis of the strategies is based on the transactional stress model by Lazarus and Folkmann (1984), and the terms problem-focused, emotion-focused and appraisal-focused are borrowed from it. According to Schütze narrative continuity in the biographical narrative interview is constituted of several “Zugzwänge”, or requirements: the requirement to close (Gestaltschließung), the requirement to depict (Darstellung) as well as the requirement to provide detail (Detaillierung). All participants deviated from these immanent requirements of narration as they displayed symptoms of dementia such as word finding difficulties or autobiographical “blanks”. Some participants discussed and reflected the symptoms of their disease whenever they abandoned the narrative structure: “yes, I’m a little, well, but I am obviously extremely forgetful. Half an hour later I don’t remember what I have eaten.” (P5:549).13 The original chronological narration was briefly abandoned in order to report on daily experiences with speech losses or with malfunctions of the executive functions. In one instance the participant revealed the signs of dementia they perceived to the interviewer when abandoning the narration: “I have also talked about this with the doctor during the last evaluation and (…) I say “there are only old people who come to see you and er that’s when the forgetting starts.” he laughed. “yes“, he says, “but you still notice it, don’t you?” I say “thank the lord, yes” (P9:1375).14 Here one can observe a striving for maintaining the self-concept by adopting a problem-focused strategy (aa): The participant is active and self-reliant in reflecting on the disease by consulting a doctor and talking to them about initial symptoms.

In contrast, other participants rarely commented on word finding difficulties, or on obviously forgetting biographical events during the conversation. The symptoms were relativized or distracted from as the following dialogue between interviewer (I) and participant (P) shows (P4:97–102)15:

|

I: “And how old are you now?” P: “Oh, I have to think about that. Born in 28. 38 48 58 68.78. What year are we in?” I: “2017.” P: “excuse me?” I: “2017.” P: “Oh. She still has. I still have a few years left. You are welcome to help yourself to cookies.” (P4: 97–102) |

The responses show a conscious avoidance strategy in the uncomfortable situation caused by the interview question. This is an example of an emotion-focused strategy (ab). Most participants identified forgetfulness as being part of the natural aging process: “what have I done, oh dear, that’s how it is when you get old, you forget half of the things.” (P10:88).16 In addition they often compared themselves to other persons their age from their social network: “well, what [the neighbor] has at 80 years old, Alzheimer’s or a part of it. Some things just don’t work anymore. I mean for me it’s the same.” (P9:1375).17 Only one person explicitly named their diagnosed dementia as such. Some participants rather described it less specifically as problems with the head: “you know, my head has gotten old. (laughs)” (P10:114).18 Apparently the disease is redefined as a “problem” and is isolated from the overall experience of health on a psychological level: “my health is good. But my head.” (P11:128).19 The participants speak fundamentally differently about dementia than they do about other diseases they have. The latter are described either as concrete disease patterns (such as cardiovascular problems, limitations of the locomotor system and deterioration of vision), or as limitations of the freedom of action and of the organization of everyday life: “I kept my theater subscription for many years, but, as somebody always had to pick me up and take care of me, because I cannot walk well anymore, you know, I let it go.” (P5:44).20 Interests, skills and abilities equally constitute the self-concept. Accordingly, in the aforementioned example the interest in theater cannot be pursued due to limitations of the mobility, and conflicts with maintaining the old self-concept. In none of the examined cases is dementia perceived as cause for abandoning an interest. A reaction to the process of forgetting is to pursue present interests such as reading and cross-word solving, for instance, even more rigorously. In order to respond to potential memory “blanks”, three of the participants wrote down important moments in their life as a reminder (strategy aa). Confronting the disease in a problem-focused way (aa) can involve the attendance of memory trainings: “once a week I attend a memory training to make sure it stays chirpy up there.” (P6:196).21 For other participants, maintaining the self-concept (strategy a) rather meant to adopt “intrapsychic processes”. This means that they looked for ways to reduce strains connected to the experienced symptoms of the disease (strategy ab). One of these ways is to interpret certain symptoms in a self-protective way. For example, forgotten information is dismissed as unimportant events, or events that happened too long ago to remember: “it has been so long. I cannot remember that.” (P7:226).22 This also led to ignoring certain symptoms and to direct the attention to basic bodily needs: “Other than that, I don’t have any complaints. Food tastes good, I sleep well” (P4:351).23 They would respond to forgetting by relativizing external norms: “I…cannot know everything. I can’t know everything from A to Z. I will be over ninety years old soon. Or already am.” (P11:140).24 Some said they actively decided not to remember negative events. In contrast to persons who adopted problem-focused strategies (aa), persons using emotion-focused strategies (ab) would cite rare visits to the doctor as proof for their good health status and leave their disease to chance: “Yes, all in all I am thankful to life that I am still healthy.” (P7:186).25 They remembered past behavior and characteristics that helped them find solutions to current problems: “you always have to take care of keeping at least a little contact to others. That has never been a problem for me. So… (laughs) if just one of them was still alive, of the relatives, they would certainly confirm. They know me, after all” (P9:493).26 This is an example for seeking emotional support via positive experiences of social interaction (strategy ab).

Instead of using strategy a, others accepted the partial loss of the self-concept: “my [daughter] always says: “Mum, you go through the door and your thought is gone” (laughs) and sometimes it really makes me laugh. That’s how it is.” (P9:1375).27 This is an example of an appraisal-focused strategy (ba) marked by a humorous and resource-oriented way of coping with the disease. For other participants, on the contrary, the modification of the old self-concept (strategy b) means to meet the disease with resignation (strategy bb): “You cannot do anything against it, that’s just exhaustion at this age.” (P10:64).28

A person’s relation to the self-concept (A) is reflected in the decision of all participants to keep on living alone in their homes. The reasons for this decision varied according to the strategy used. Those who adopted a problem-focused behavior towards the disease situation (aa) consciously perceived the symptoms, but also saw sufficient room for action to continue living alone. Moving to a care center, for instance, would be equal to losing control over the disease situation for them. Persons who adopted an emotion-focused strategy (ab) perceived the symptoms less consciously. For them, living alone is a matter of course and is not characterized by fears and worries. They neither considered an alternative form of living, nor moving to a care center as an option: “That would mean I must have something. That I have an illness or something. If I cannot live here by myself or I’m not allowed to.” (P7:343).29 Participants adopting an appraisal-focused strategy (ba) perceived living alone with dementia as a challenge: “I have to get used to getting by myself. I am convinced, I can make it.” (P12:66).30 A positive view on the disease situation resulted in reacting to challenges during the process of dementia and to appraise risks and need for help related to living alone realistically (e.g. by using formal help services). The more influence the person believed to have had on past life events (C), the stronger they did so with regard to the disease situation by adopting a problem-focused or an appraisal-focused strategy (aa, ba). If the person thought to have had little influence on past life events (C), they developed less autonomous solutions (ab, bb). The latter withdraw from social life and resign, compared to persons who adopt emotion-focused strategies (ab). As mentioned in the beginning, the self-concept is also formed by other people’s reactions to the self. Reflected evaluations (e.g. perceived social exclusion) are internalized and result in according behavior (e.g. withdrawal due to shame): “Alone, that is the problem of an old person. Nobody wants to be together or gets together sometimes.” (P12:44).31

Consequences (E): Maintaining or modifying the self-concept – “This is me!”

The consequence (E) of the adopted action strategy (D) is that persons with dementia enter into a (new) relationship with the self. The consequence of reflecting on the self-concept (A) can be to either maintain the old self-concept (c), or to develop a new one (d). The data shows that this is especially reflected in the participants’ depiction of several experienced and lived social roles and of their subjective age. All participants had in fact experienced a loss of their social role when they retired, were widowed or when their children moved out. Those who wanted to maintain their old self-concept during the course of dementia (strategy a) upheld former social roles in the present and in the future (consequence c). Biographical knowledge concerning their profession, for instance, was used by persons who had a distorted perception of their symptoms, or who denied their symptoms in such a way as to maintain their identity and their self-concept: “I am a professional nurse, you know. That’s why I have many elderly people up here at our place that I have to care for from time to time.” (P4:354).32 Persons who adopted a problem-focused strategy, in contrast, mentioned gardening and running the household as activities. This designs a changed understanding of their social roles rather than a loss of their professional roles. Persons who gradually withdrew from social roles and professional obligations, and who were willing to abandon roles related to their old self-concept (strategy b) developed a new one (consequence d): „I am saying I used to be an early bird but now I am so lazy now I get up only at half past eight. I have time.” (P8:1045).33 Subjective age likewise affects maintaining the old self-concept or developing a new one. For persons who adopted strategies for maintaining their self-concept (a) age and getting older felt less threatening (consequence c): “I can’t sit still and mope yet, I am too fit for that still. Ok? I am very simply too fit for that still.” (P12:76).34 This was also true for individuals who did not remember their age, or who denied their age: “I still cannot believe that I am this old. Oh god, oh god” (P9:380).35 While these persons mainly maintained their self-concept, other persons developed a new one (consequence d) by abandoning parts of their old self-concept (strategy b). Benefits of old age were embedded in a new, positive self-concept: “When you’re old, you’re authorized to such judgement.” (P9:1432).36 Others felt they were at the mercy of the aging process. This feeling resulted in a new, negative self-concept: “Of course I have not anticipated getting this old, you know. But that’s generally the case nowadays that people get older, right. There are many reasons for that” (P5:352).37

Conclusion and Discussion of Results

Based on the data we developed a theoretical model of the dementia-specific self-concept. The narratives show that perceiving and experiencing the disease situation are primarily characterized by the person’s relation to the self-concept rather than by dementia-specific symptoms (such as memory dysfunctions, and dysfunctions of spatial and temporal orientation, or linguistic impairments). The medical definition of dementia (the objective symptoms) thus stands in opposition to the individuals’ subjective perception of the disease situation. The subjective perception leads to reflecting on the self-concept using either one of two action strategies resulting in either maintaining or modifying the old self-concept.

Contextual Conditions

Several contextual conditions determine how a person reflects on the self-concept during the process of dementia. The analysis of the data involved a conceptualization based on the construct of internal versus external locus of control by Rotter [11] which helped identify (premorbid) personality traits. Specifically, we looked at expectations participants had towards certain events that followed their own actions. Differences between internal and external loci of control based on the example of the participants’ professional biography were found: Some participants experienced their profession in an internal manner (residing in their behavior, e.g. professional choices and actions). External locus of control manifested itself in the form of depending on others, and especially, in the case of women, on the partner (social-external locus of control). Conditions related to a specific generation influence certain personality traits such as locus of control [41]. The data reveals a traditional understanding of typical gender roles of the 60s: the woman as housekeeper and mother, the man as moneymaker and provider. The results concerning the contextual conditions (locus of control) show opportunities and living conditions specific to this generation, which can be retraced to old age as well as to the disease [42]. Since experiences of childhood, youth and young adulthood permanently influence later loci of control [43], these areas were taken as a basis for the interpretation of dementia as the critical life event. In particular, positive connections between (premorbid) internal locus of control and the problem-focused strategy (aa) as well as the appraisal-focused strategy (ba) were found: Persons with internal locus of control took specific measures in order to confront the disease and challenges tied to it. Persons with external locus of control rather viewed luck, bad luck, or fate as reasons for their health-status. Their coping with dementia resulted in a “feeling of helplessness” which manifested itself via emotion-focused strategies (ab) or resignation (bb). The transfer from past locus of control to present ones should be viewed critically as it might be a variable personality trait [44]. With advanced age a strong internal locus of control becomes significantly less probable [45]. In an American study persons with dementia report on events of losses of control (in terms of health) that are due to the unpredictability of the course of the disease [46]. Additionally, it is not entirely clear whether we can speak of premorbid personality traits and behavior. These may well be traits that are rather constructed or distorted in the autobiographical memory, since we retrospectively asked about the biographical locus of control during the interview.

Action Strategies

The field of health care approaches illness perception in dementia from a symptomatic or deficit-oriented point of view. While this view merely regards neuro-cognitive dysfunctions that lead to the persons’ impaired ability to reach insight [10], we choose a different perspective. Our model includes contextual factors (C) and action strategies (D) that go beyond this deficit-oriented view and that explain the experience and behavior of persons with dementia. We assume that the person’s current relation to the self-concept (A) is linked to passed (premorbid) strategies of behavior and personality traits (C). The strategies closely follow the theoretical elements of the transactional stress and coping model by Lazarus and Folkmann [12]. In their model, the first step is to determine the meaning the disease situation has for a person (primary appraisal). In this study the diagnosis is mentioned only in one case. For the majority of the participants the appraisal of the disease situation is embedded in the narrations on the relation to the self-concept. Problem-focused coping strategies (aa) involve an increasing number of visits to the doctor, attendance to memory trainings, or seeking information as reactions to a threatening loss of the old self-concept (e.g. loss of cognitive abilities). In contrast, emotion-focused coping strategies (ab) involve an unwillingness to accept having a disease by trivializing or denying the symptoms, for example, as reactions to a threatening loss of the self-concept. Often the persons interpreted their symptoms in a self-protective manner. Other studies have equally found that elderly persons often explain memory blanks by referring to the unimportance of the forgotten information [47]. Emotion-focused coping strategies also involve comparisons: “I do not feel ill, although I am not as industrious and as fit as I used to be.” (B4:309). According to Social Comparison Theory [48] individuals permanently compare themselves to their social environment. This entails that the self-concept is always related to the social environment. These comparisons occur especially in insecure situations. In such situations the participants primarily compared themselves to people their age from their social environment – according to Festinger the persons they compare themselves to are persons who share central traits of their own self-concept as the following quote shows: “It’s enough that I can still walk around. When I see that the others, they are so much younger, ten years younger and are being driven around back and forth every day.” (B9:246). In this example the person appraises dementia in relation to other persons’ diseases (impaired mobility). In a longitudinal study on the development of the self-concept of persons after a leg amputation, Klein [49] observed that the persons moved from physical activities to intellectual exchange and socio-communicative activities. This shift in perceiving their existence was entirely reversed for some persons with dementia: They, in contrast, emphasized their high bodily activities (walks, household etc.) and avoided direct communication: “And I am so happy every time I get mail, you can always read that again, but a phone call, that’s out too” (B9:1375). Rather than being a coping strategy, focusing on bodily rather than psychological conditions, might be specific to a generation (cohort effect) that lacks sensibility for psychological diseases [50].

Consequences

The adopted strategies result in maintaining the old self-concept (c) or in developing a new self-concept (d). When maintaining the self-concept (consequence c from strategy a) a positive self-concept results from a successful experience of personal skills, aging and living social roles. Disregarding or denying symptoms using an emotion-focused strategy (ab) enabled the person to maintain the old self-concept. Modifying the self-concept (consequence d from strategy b) resulted in a positive new self-concept when the loss of certain skills was viewed as a challenge, old age was accepted, and the person voluntarily withdrew from former social roles. Pinquart [47] defines the self-concept of the elderly as a sensitive indicator for the specific life situation and the ability to deal with the latter. Consequently, the phenomenon of reflecting on the self-concept is observable in all elderly people. As in this study, in other studies with elderly people without dementia, the participants believed to be much younger than they actually [5, 6]. The example of subjective age shows that the self-concept can deviate from objective reality [49]. In contrast to other elderly people, persons with dementia are only rarely capable of realistically assessing their current life situation. Often persons with dementia located themselves in a time prior to the onset of dementia, and they did not know their current age. They had a distorted perception of social roles, i.e. they believed to occupy roles that they objectively did not occupy any longer (as the example of the pensioner with dementia who perceived of themself as practicing nurse illustrates).

Implications

According to the World Health Organization the development and the maintenance of functional abilities (such as meet their basic needs, to learn, grow and make decisions; to be mobile) is a prerequisite for healthy aging: “Functional ability comprises the health-related attributes that enable people to be and to do what they have reason to value” [2, p. 28]. Departing from this definition our model of the dementia-specific self-concept is process-based rather than phase-based. This is because reflecting on the self-concept (“Who am I?”) is tied to the course of the disease (early, middle and late dementia) (B), on the one hand, and to contextual conditions (C) that are subject to change, on the other. The components interact with one another. This leads to new action strategies (D) and consequences (E): For instance, the progression of the disease entails increasing memory dysfunctions (B). Contextual conditions (C) change because making recourse to autobiographical material becomes more difficult. The relation between the requirements caused by the new symptoms and the perception of personal knowledge resources (such as using premorbid strategies of behavior) equally changes. Strategies used for the person’s relation to the self-concept can differ from strategies used previously in the process of dementia, and can lead to new answers to the question “Who do I want to be?”.

The question of which strategy is more helpful (adaptive) for a person’s relation to the self-concept and which is less helpful (maladaptive), cannot be answered precisely [51]. The advantage of a problem-focused strategy (aa) lies in an individual actively confronting their disease. In this case, a person with dementia may participate in making decisions concerning treatment options with their doctors. This strategy is only helpful to a limited extent as dementia is irreversible, and as the disease can only be temporarily stopped from progressing, and complaints (such as depression) can only be alleviated. Knowing about the uncontrollability of the disease can be a heavy burden for the individual. In contrast, the advantage of an emotion-focused strategy (ab) lies in seeking ways that help avoiding high emotional strains. This can lead to a higher quality of life. A lack of willingness to accept the disease (distraction, denial of risks, overestimating one’s personal abilities), however, can equally lead to serious dangers in everyday life, and can delay or prevent treatments with or without medication [52]. When adopting an appraisal-focused strategy (ba), individuals accept the disease and are able to evaluate risks realistically. At the same time a premature willingness to accept the disease can lead to insufficient consideration of potential treatments. If neither of these strategies is adopted, coping with the disease can come to mean resignation and heighten the risk of social isolation (strategy bb). The dementia-specific self-concept offers a theoretical approach to the analysis of the individual experience and coping with the disease situation of persons with dementia. A long-term goal of this research is to deduce implications for health care practices, in order to meet the beliefs, expectations and needs of persons with dementia in an individual, suitable, and sensitive way during the course of the disease.

Discussion of Methods

Biographical narrations offer an access to the participants that is especially suitable in the context of dementia. Memory dysfunctions caused by dementia affect semantic content in long-term memory (including common knowledge and word meanings, for instance), but do not affect episodical and autobiographical memory [53]. Childhood experiences, family/partnerships, as well as professional backgrounds are areas of life that were remembered by all participants and that could be used for the analyses. Another advantage was that the interviews were conducted in the homes of the interviewees, and objects such as pictures, photographs or religious symbols could be used as narrative stimuli. Accordingly, interviews not conducted in the participants’ homes were significantly shorter. Findings from social gerontology and from the care of the elderly show that reflecting on one’s biography is health-promoting and has positive effects on memory [33]. The need to turn to early memories and remember personal life events is a central result of the LUCAS study [54, 55] At the same time negative experiences, such as experiences of war, may re-emerge during biographical narrations. However, the method is open and sensitive to dementia in that it allows the participants to determine relevant topics and to avoid sensitive subjects if desired. Consequently, contents that were not remembered by the participants, or that that they did not wish to discuss remained unrecorded. This also means that the participants may have consciously avoided depicting their disease for fear of shame or stigmatization. Therefore, it cannot be excluded that the data contains reporting bias. Three interviews were conducted in the presence of family caregivers and advisors who often interrupted the participants’ narrative and related biographical events from their perspective. Here differences between self-perception and the perception by others became apparent. The comments by the third party may have influenced both the researchers’ analyses and the participants’ narration to a certain extent. Dementia was neither mentioned by the researchers when delivering information on the study, nor during the interviews, as this might have influenced the biographical narration, and it might have caused emotional strains for the participants. At the same time this procedure raises the ethical question whether the tabooing of dementia is supported by avoiding a direct confrontation with the disease. Presuppositions regarding the field of research that are issued from literature research, and from individual, as well as socio-cultural experiences were recorded in a research diary and reassessed deductively on the basis of the empirical data. We decided against a member check [36] with which to retrace the results to the interviewees and verify the results for two reasons: On the one hand, we could not establish to which extent a confrontation with the topics dementia and need for care might have a negative impact on the participants. On the other hand, the interview data represent but a snapshot of remembering, experiencing, and acting. Due to the long-time span between data collection and data analysis, but also due to the progression of the disease, the results could not be replicated with the same participant. Instead, we agreed on the credibility and the meaning of the data in numerous research meetings with other social researchers and non-professionals. Despite methodological limitations and challenges inherent in dementia research, explanations regarding illness perception and perception of the self that would have remained unnoticed without an open and qualitative research approach were found. In order to fully exploit the potential of research with persons with dementia, further development of research designs that enable a higher degree of participation for people with dementia along the entire course of the disease is needed.

Conflict of Interest : The authors of the study (ethic number: 3533–2017) have no conflict of interest to report.

Acknowledgement

A special thanks to our interviewees for the participation in our study and their willingness to tell about their life story. We are furthermore grateful to all the persons and institutions, wo helped us with recruiting and getting field access: therapists and physiotherapists, legal guardians, outpatient nursing services, information centers, self-help groups, volunteers, media and close relatives.

References

- Baltes Margret M, Baltes Paul B (1990) Successful aging. In: Baltes Margret M, Baltes Paul B (eds.). Perspectives from the behavioral sciences. European Network on Longitudinal Studies on Individual Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- World Health Organization (2015) World report on ageing and health. Geneva: WHO.

- Baumeister Roy F (1998) the self. In: Gilbert Daniel Todd, Fiske Susan T, Gardner Lindzey (eds.). The handbook of social psychology. (4th edn). Boston, New York: Distributed exclusively by Oxford University Press, p. 680–740.

- Kernis Michael Howard M, Goldman, Brian Middleton (2003) Stability and variability in self-concept and self-esteem. In: Mark R. Leary und June Price Tagney (eds.). Handbook of self and identity. New York: The Guilford Press, p. 106–127.

- Essex Marilyn J, Klein Marjorie H (1989) The Importance of the Self-Concept and Coping Responses in Explaining Physical Health Status and Depression among Older Women. In: Journal of Aging and Health 1: 327–348.

- Weiss David, Lang Frieder (2012) “They” are old but “I” feel younger: age-group dissociation as a self-protective strategy in old age. In: Psychology and aging 27: 153–163.

- Douglas Heather, Georgiou Andrew, Westbrook Johanna (2017) Social participation as an indicator of successful aging: an overview of concepts and their associations with health. In: Australian health review: a publication of the Australian Hospital Association 41: 455–462.

- Filipp Sigrun-Heide, Klauer Thomas (1991) Subjective well-being in the face of critical life events: The case of successful copers. In: Fritz Strack, Michael Argyle and Norbert Schwarz (eds.). Subjective well-being. Oxford: U.K.: Pergamon, p. 213–234.

- Strack Fritz, Argyle Michael, Schwarz Norbert (eds.) (1991) Subjective well-being. Oxford: U.K.: Pergamon.

- Iqbal Khizra, Amin Rizwana (2018) Negative Life Events and Mental Health Among Old Age People: Moderating Role of Social Support. In: Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research 33: 401–412.

- Rotter Julian B. (1990): Internal versus external control of reinforcement: A case history of a variable. In: American Psychologist 45: 489–493.

- Lazarus Richard S, Folkman Susan (1984) Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

- Busch Albert, Spranz-Fogasy Thomas (2015) Handbuch Sprache in der Medizin. [Handbook language in medicine.] Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton (Handbücher Sprachwissen, 11).

- Mejia-Arango Silvia, Gutierrez Luis Miguel (2011) Prevalence and incidence rates of dementia and cognitive impairment no dementia in the Mexican population: data from the Mexican Health and Aging Study. In: Journal of aging and health 23: 1050–1074.

- Prince Martin James (2015) World Alzheimer Report 2015: the global impact of dementia: an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends: Alzheimer’s Disease International.

- Illiger Kristin, Walter Ulla, Koppelin Frauke (2018) Alleinlebende mit Demenz – Eine Datenanalyse der ambulanten Pflege in einer kreisfreien Großstadt. [Persons living alone with dementia – a data analysis of outpatient care in an independent city] In: Pflegewissenschaft 20: 437– 444.

- Bleck Christian, van Rießen Anne, Knoop Reinhold (2018) Alter und Pflege im Sozialraum. Theoretische Erwartungen und empirische Bewertungen. [Age and care in the social environment. Theoreticalexpectations and empiricalvaluations.] Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH.

- Coyle Caitlin E, Dugan Elizabeth (2012) Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. In: Journal of aging and health 24: 1346–1363.

- Illiger Kristin, Walter Ulla, Koppelin Frauke (2017) Demenz im Fokus der Gesundheitsforschung: Eine vergleichende Analyse aktueller Altersstudien. [Dementia in the focus of health research. A comparative analysis of current ageing studies.] In: Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz 60: 563–571.

- Leicht Hanna, Berwig Martin, Gertz Hermann-Josef (2010): Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease: the role of impairment levels in assessment of insight across domains. In: Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 16: 463–473.

- Gove Dianne, Diaz-Ponce Ana, Georges Jean, Moniz-Cook Esme, Mountain Gail, et al. (2018) Alzheimer Europe’s position on involving people with dementia in research through PPI (patient and public involvement). In: Aging & mental health 22: 723–729.

- Orfei Maria Donata, Assogna Francesca, Pellicano Clelia, Pontieru Francesco Ernesto, Caltagirone Carlo, Pierantozzi Mariangela et al. (2018) Anosognosia for cognitive and behavioral symptoms in Parkinson’s disease with mild dementia and mild cognitive impairment: Frequency and neuropsychological/neuropsychiatric correlates. In: Parkinsonism & related disorders 54: 62–67.

- Malek Hédi Ben, Philippi Nathalie, Botzung Anne, Cretin Benjamin, Berna Fabrice, Manning Liliann, Blanc Frédéric (2019) Memories defining the self in Alzheimer’s disease. In: Memory 27: 698–704.

- Byrne Barbara M (1996) Measuring self-concept across the life span: Issues and instrumentation. Washington: American Psychological Association.

- Riemann Gerhard (1987) Das Fremdwerden der eigenen Biographie. Narrative Interviews mit psychiatrischen Patienten. [The Alienation ofone’s own biography. Narrative interviews with psychiatric patients.] München: Fink.

- Savundranayagam Marie Y, Ryan Ellen B, Anas Ann P, Orange JB (2007) Communication and Dementia. In: Clinical Gerontologist 31: 47–63.

- Schütze Fritz (1983) Biographieforschung und narratives Interview. [Biography research and the narrative interview.] In: Neue Praxis 13: 283–293.

- Hermanns Harry (1995) Narratives Interview. [Narrative interview] In: Flick Uwe, Kardoff Ernst von, Keupp Heiner, Rosenstiel Lutz von, and Wolff Stephan (eds.). Handbuch qualitative Sozialforschung. [Handbook qualitative Social Research.] (2nd edn). Munich: Psychologie Verlags Union, p. 182–185..

- Kruse Jan, Schmieder Christian (2014) Qualitative Interviewforschung. Ein integrativer Ansatz. [Qualitative interview research. an integrative approach.] Weinheim: Beltz Juventa (Grundlagentexte Methoden).

- Phillips Susan P, Auais Mohammad, Belanger Emmanuelle, Alvarado Beatriz, Zunzunegui Maria-Vitoria (2016) Life-course social and economic circumstances, gender, and resilience in older adults: The longitudinal International Mobility in Aging Study (IMIAS). In: SSM – population health 2: 708–717.

- Ashida Sato, Heaney Catherine A (2008) Differential associations of social support and social connectedness with structural features of social networks and the health status of older adults. In: Journal of aging and health 20: 872–893.

- Glaser Barney G, Strauss Anselm L (2017) Theoretical sampling. In Sociological methods: Routledge 105–114.

- Panke-Kochinke Birgit (2014) Menschen mit Demenz in Selbsthilfegruppen. Krankheitsbewältigung im Vergleich zu Menschen mit Multipler Sklerose. Weinheim: Beltz Verlagsgruppe.

- Selting Margret, Auer Peter, Barth-WeingartenDagmar, Bergmann Jörg, Birkner Karin, et al. (2009) Gesprächsanalytisches Transkriptionssystem 2. [Language-analysis-basedtranscriptionsystem 2.] In: Gesprächsforschung – Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 10: 353–402.

- Glaser Barney G, Strauss Anselm L (1999) The discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. 4. Paperback printing. New Brunswick: Aldine.

- Steinke Ines (2010) Quality criteria in qualitative research. In: Flick Uwe, Kardorff Ernst von, Steinke Ines (eds.). A companion to qualitative research. repr. London: Sage.

- Böhm Karin, Tesch-Römer Clemens, Ziese Thomas (2009) Gesundheit und Krankheit im Alter. [Health and illness in old age.] Berlin: Robert Koch-Inst (Beiträge zur Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes).

- Böhm Andreas, Legewie Heiner, Muhr Thomas (2008) Kursus Textinterpretation: Grounded Theory. [Text interpretation course: grounded theory]. Available online via https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/document/2662/1/ssoar-2008-bohm_et_al-kursus_textinterpretation_grounded_theory.pdf

- Strauss Anselm L, Corbin Juliet (1990) Basics of qualitative research. Newbury Park: Sage.

- Strübing Jörg (2018) Grounded Theory und Theoretical Sampling. [Grounded Theory and theoretical sampling]. In: Baur Nina, Blasius Jörg (eds.). Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung [Handbook methods in empirical social research]. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden 51: 525–544.

- Hülür Gizem (2017) Cohort differences in personality. In: Personality Development Across the Lifespan, 519–536.

- Pasero Ursula, Backes Gertrud, Schroeter Klaus R (2007) Altern in Gesellschaft. Ageing – diversity – inclusion. [Aging in Company of Others.] Wiesbaden: VS Verl. für Sozialwiss.

- Steptoe A, Poole L (2016) Control and Stress. In: Fink George (eds.). Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior. Amsterdam: Elsevier, p. 73–80.

- Pudrovska Tetyana (2015) Gender and health control beliefs among middle-aged and older adults. In: Journal of aging and health 27: 284–303.

- Schnee Melanie, Grikscheit Florian (2013) Gesundheitliche Kontrollüberzeugungen von Patienten in Disease Management Programmen. [Health Locus of Control of Patients in Disease Management Programmes] In: Gesundheitswesen (Bundesverband der Ärzte des Öffentlichen Gesundheitsdienstes (Germany) 75: 356–359.

- Portacolone Elena, Rubinstein Robert L,. Covinsky Kenneth E, Halpern Jodi, Johnson Julene K (2019): The Precarity of Older Adults Living Alone With Cognitive Impairment. In: The Gerontologist 59: 271–280.

- Pinquart Martin (1998) Das Selbstkonzept im Seniorenalter. [The self-concept in old age]. Weinheim: Beltz.

- Festinger Leon (1954) A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. In: Human Relations 7: 117–140.

- Klein Thomas (2003) Selbstkonzept und Coping-Prozesse bei Patienten nach einer Amputation. Eine Längsschnittstudie zur Entwicklung des Selbstkonzepts und zum Prozess der Bewältigung bei Patienten nach einer Beinamputation. [Patient self-concept and coping processes after an amputation. A longitudinal study on the development of the self-concept and the process of how patients manage a leg amputation.] Dissertation. Dortmund.

- Friederich Hans-Christoph, Hartmann Mechthild, Bergmann Günther, Herzog Wolfgang (2002) Psychische Komorbidität bei internistischen Krankenhauspatienten-Prävalenz und Einfluss auf die Liegedauer. [Psychiatric comorbidity in medical inpatients. Prevalence and effecton the length of stay.] In: Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 52: 323–328.

- Moritz Steffen, Jahns Anna Katharina, Schröder Johanna, Berger Thomas, Lincoln Tania M, Klein Jan Philipp, Göritz Anja S (2016) More adaptive versus less maladaptive coping: What is more predictive of symptom severity? Development of a new scale to investigate coping profiles across different psychopathological syndromes. In: Journal of affective disorders 191: 300–307.

- Heßmann Philipp, Dreier Maren, Brandes Iris, Dodel Richard, Baum Erika, et al. (2018) Unterschiede in der Selbst- und Fremdbeurteilung gesundheitsbezogener Lebensqualität bei Patienten mit leichter kognitiver Beeinträchtigung und Demenz vom Alzheimer-Typ. [Differences between self- and proxy-assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with mild cognitive impairment and alzheimer’s disease.] In: Psychiatrische Praxis 45: 78–86.

- Bartsch Thorsten, Falkai Peter (2013) Gedächtnisstörungen. Diagnostik und Rehabilitation. [Memory Disorders. Diagnostic and Rehabilitation.] Berlin: Springer.

- Dapp Ulrike, Fertmann Regina, Anders Jenny, Schmidt Silke, Pröfener Franz, et al. (2011) Die Longitudinal-Urban-Cohort-Ageing-Studie (LUCAS). [The Longitudinal Urban Cohort Ageing Study (LUCAS).] In: Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie 44: 55–72.

- Dapp Ulrike, Anders Jennifer, Renteln-Kruse Wolfgang von, Golgert Stefan, et al. (2012): The Longitudinal Urban Cohort Ageing Study (LUCAS): study protocol and participation in the first decade. In: BMC geriatrics 12: 35.

1 German original: “Könnten Sie mir von Ihrer Lebensgeschichte erzählen? Am besten beginnen Sie mit der Geburt, mit dem kleinen Kind, das Sie einmal waren, und erzählen dann all das, was sich so nach und nach in Ihrem Leben zugetragen hat, bis zur Gegenwart. Sie können sich dabei ruhig Zeit lassen, auch für Einzelheiten, denn für mich ist alles interessant, was Ihnen wichtig ist.”

2 The terms are taken from the classification of old age [37] The age categories correspond to the frequency distribution of people living alone with dementia according to Illiger et al. 2018 [16].

3 „sag mal grad, wie hieß die grad, zur frauenfachschule, wo ich dann aber nicht weiter gemacht habe, weil ich inzwischen wusste, dass ich [meinen Mann] heiraten würde“ (B6:236)

4 „nein, das [weiter arbeiten] konnt ich nicht. ICH musste ja auf die kinder aufpassen. und so. und essen machen und so. und die wOHnung sAUber halten.“ (B7:274)

5 „ich hab geArbeitet, ich hab meine familie nicht gut, sondern sEHr gut dUrchgebracht“ (B12:18)

6 „als mein mann dann fertig war, mit dem studium und die stelle dann in X-Stadt kriegte, bin ich dann hinterhergedackelt.“ (B6:121)

7 „da sind es nun zwei jungs. er hat da nicht mehr erlaubt, ne.“ (B7:173)

8 „WAs ich gemacht hab: aus allem immer das beste“ (B9:212)

9 „ich kONnte und wOLlte das nicht dass Irgendeiner bestIMmt (2.0) DAS konnte ich nicht hAben.“ (B12:24)

10 „ich bin SEHr zufrieden mit meinem schicksal, bin ich sehr zufrieden.“ (B11:72)

11 „naja, wir haben ja auch glÜCK gehabt.“ (B9:559)

12 „wohl nen engel“ (B7:80)

13 „ja, ich bin n bisschen, gut, aber ich bin natürlich total vergesslich. ich weiß ne halbe stunde später nicht mehr was ich gegessen habe.“ (B5:549)

14 „ich hab auch mitm ARzt darüber gesprochen als ich bei der letzten auswertung war und (…) ich sage „zu ihnen KOMMen ja nur alte leute und und äh da fängt jetzt das verGESSen an“. musste er lachen. „ja“, sagt er, „aber sie mERKens noch, wa?” ich sag „na gott sei dank ja” (B9:1375)

15 I: „und wie alt sind sie jetzt?“

B: „oh, jetzt muss ich nachdenken. jahrgang 28. 38 48 58 68.78. was haben wir jetzt?“

I: „2017.“

B: „wie bitte?“

I: „2017.“

B: „oh. da muss se noch. ja, dann muss ich noch ein paar jährchen. sie dürfen sich gerne auch

kekse nehmen.“ (B4:97–102) In the German version, the letter B for “Betroffener” is used.

16 „was hab ich n denn gemacht o gott, so is das wenn man ALt wird, vergisst man die hälfte.“ (B10:88)

17 „naja was hat [der nachbar] nu mit 80 jahre, ALZheimer oder n TEil davon (4.0) es läuft eben alles nicht mehr so. (2.0) ich meine bei MIR is es auch so.“ (B9:1375)

18 „jaja, mein kopf ist schon alt. (lacht)“ (B 10:114:)

19 „gesUNDeitlich fühl ich mich gut. aber mit dem kOPF.“ (B11:128)

20 „hatte noch lange jahre n theaterabo, aber weil mich da auch immer jemand abgeholt hat und sich um mich kümmern muss, weil ich ja nicht mehr richtig gehen kann, ne, hab ich das auch aufgegeben.“(B5:44)

21 „ich hab einmal die woche ein gedächtnistraining, damit das da oben auch munter bleibt.“ (B6:196)

22 „das ist solange her. da kann ich mich gar nicht mehr erinnern.“ (B7:226)

23 „ansonsten habe ich gar keine beschwerden. essen schmeckt mir, schlafen kann ich gut.“ (B4:351)

24 „ich….kann ja nicht ALles wissen. kann ja nicht alles wiSSen von hiEr bis dA. ich bin über NEUNzig bald. oder bIN schon.“ (B11:140)

25 „ja, eigentlich bin ich dem leben dankbar, dass ich noch gesund bin.“ (B7:186)

26 „man muss IMMEr dafür sorgen, dass man so n bisschen kontakt hat. und das ist mir noch NIE schwergefallen. also…(lacht) ja wenn davon noch einer LEBen würde, von den verwandten, die könnten das nur bestätigen. die kennen mich ja auch.“ (B9:493)

27 „meine [tochter] sagt immer „mutti du gehst durch n TÜRrahmen und denn is der gedanke weg“ (lacht) und manchmal muss ich WIRKlich lachen. SO ist das eben.“ (B9:1375)

28 „man kann ja nichts gegen machen, das ist ja verschlEIß, in dem alter.“ (B10:64)

29 „da muss ich ja irgendwie was haben. muss ich ja dann krank sein oder wie. dass ich hier alleine nicht leben kann oder nicht mehr leben darf.“ (B7:343)

30 „ich mUss mich daran gewÖhnen allEine zurEcht zu kommen. ich bin davon überzEUgt, ich schAffe es.“ (B12:66)

31 „allEINe, das ist eben das problEm. (3.0) eines älteren menschen. (2.0) keiner will mitnander oder tUt miteinander mal.“ (B12:44)

32 „ich bin ja krankenschwester von beruf. Insofern habe ich viele ältere leute hier bei uns oben, wo ich mich mal ab und zu sehen lassen muss.“ (B4:354).

33 „ich sage ja, ich war n frühaufsteher (2.0) aber JETZt bin ich so bequEem (1.0) jetzt steh ich erst um halb ACHt auf. Ich hab Zeit. (2.0)“ (B8:1045)

34 „HINsetzen und TRÜbsal blasen kAnn ich noch nicht, dAfür bin ich eben noch zu fIt. Ja? (2.0) dAfür bin ich eben GANZ Einfach noch zu fIT.“ (B12:76)

35 „Ich kann immer gar nicht glauben, dass ich schon so alt bin. Ach gott, ach gott.“ (B9:380)

36 „Wenn man so ALT ist, kann man sich das Urteil ja erlauben.“ (B9:1432)

37 „ich hab natürlich nicht geahnt, dass man so alt wird, ne. Aber es ist ja generell so, dass die leute heute älter werden, ne. Daran ist vieles schuld“ (B5:352)