Abstract

The widespread use of gender-based violence, especially against women, has been identified not only as a legal, but also as a major public health problem. Especially in Asia, traditional practices reflecting local health belief models lead to a number of major has related partitions, which include gender-based violence. Not only in India, but also in Nepal such traditional practices are wide spread. In Nepal, the most common problem is the “Chaupadhi” practice of menstrual segregation that leads to the death of women every year.

Methodology: in our qualitative study we used different sources including political party programs and focus interviews in the Bharatpur region of Nepal to explore the cultural and health belief models that could contribute to lead different population groups to use menstrual segregation and other forms of gender-based violence such as rape. Results we identified a number of categories [health belief systems] that we are part of gender-based identities and this forms of gender-based violence as reflected in interviews and the public discourse. Conclusions: willingness to commit or permit violence is reflected in health belief systems and identity building, and a number of recommendations will be presented that we are drawn up as a reassignment of our project to reduce gender-based violence in Nepali communities.

Keywords

Women, Public Health, Menstruation, Rape, Gender Based Violence, Nepal

Background

One in three women worldwide experience some form of violence in their lifetime. Women are two-thirds of the global illiterate population, work one to three hours and two to ten times more respectively per day compared to men the “second shift” (household chores and caring for children, elderly and sick) and earn 10 to 30 percent less than men in the employment sector (ICRW, 2018) [1]. These exemplify the effects of pervasive patriarchal norms, and inequitable society which constraints women to fill specific gender roles which are attributed with low value, little power and put them at a higher risk for violence, poor health and disease, poverty, and other inequitable adversities (USAID, 2015) [2] One of the worst examples of gender inequity and inequality with long term mental health impact is exemplified through gender-based violence perpetrated by men and boys to women and girls (ICRW, 2018) [3]

GBV is a type of violence that is based on, and propelled by the defining genders and their perceived normative roles within society. It disproportionately impacts women both in prevalence and its consequences due to women’s inferior position in society [4]. GBV has mental, physical, psychological, social, and sexual consequences which are exacerbated due to their gender. Within the various types of GBV, we can distinguish between highly visible and “invisible” GBV; with visible including sexual harassment, domestic violence, physical violence, and rape and invisible Menstrual Restriction (MR).

The relationship between the visible violence, like rape and the invisible menstrual restriction is a reciprocal relationship where MR aids in the construction of behavior like rape. In Nepal, the majority of girls and women (89%) follow MR practices and close to half of all women (48%) reported experiencing violence in their lifetime, while majority of young women (74%) report experiencing sexual violence (UNFPA Nepal, 2014). MR (in Nepali in the most dramatic form as “Chaupadhi” [5]) includes dangerous practices that leads to the death of women every year due to infections or snakebite during segregation in inadequate housing [6] and is usually enforced by the family and community [7]. Cardoso reported high exposure rates in a recent study [8], and reported that “nearly three out of four women (72.3%) reported experiencing high menstrual restriction, or two or more types of menstrual restriction”. Rhanabat reported that is his household sample 21% of households used Chaupadi. And that the “conditions of livelihood, water facility, and access during menstruation and the Chaupadi stay was associated (P < .001) with the reproductive health problems of women” [5].

Objective: The general objective was to examine the construction of men’s attitudes, perceptions, and behavior in relation with Menstrual Restriction and Rape to ensure Gender Equality and Human Rights. The specific objectives were:

- To understand the construction of attitudes, perception, and behavior of men

- To explore the relationship of men’s attitudes, perception, and behavior regarding gender-based violence: Menstrual Restriction (MR) and Rape

- To identify “Health belief models” about menstruation in men that might justify MR.

Methodology: The qualitative approach was used with primary and secondary sources were used. Primary sources included in-depth interviews, focus groups, observational research (participant observation) and interviews performed with a sample of key position holders of key political leaders of the Nepal Communist Party (CPN), Nepali Congress (NC) and Rastirya Prajatantra Party (RPP). As secondary sources we analysed the manifestos of respective political parties used for the last election 2017 and 2018. Research was conducted in July to October, 2018 in Bharatpur Metro Municipality, Bharatpur, Chitwan, Nepal.

We followed the assumption that the observational and field research would be contradicted or confirmed by secondary sources, and combination of both strategies would strengthen the validity and representative nature of observational and focus group data. We choose manifestos of respective political parties based on the assumption that the language, and implicit and explicit concepts expressed in those public populist documents would best reflect a key part of the guiding principles, popular discourse and planned strategies in the Nepalese society, which we see as a nation state, not as a mere conglomerate of the multiple small ethnic minorities that are part of the countries` population. Further, Nepali as a “common national” language was used reflecting the country wide developments that have installed Nepali as a shared common language of everyday live. The chosen samples include both people in everyday situations as also persons in “official” roles where statements could be expected to be more considered then in “free” everyday live conversations.

Findings and Discussion

Objective 1: To understand the construction of attitudes, perception, and behavior of men

Unconsciously gender roles learned from their male and female members at family and neighborhood and gradually expanded to their public spaces such as school, party or any social activities. The most common age of learning is 6-8, ranging from a young child at age 5 to oldest at age 12. The use of Gendered Language in the home and outside initially separates “boys” from “girls”, establishing direct and indirect gender norms.

“I was about 5-6 years old, I knew from “parivarik (family culture)” language where boys are called “bhai (little brother),and girls are called “nani (little girl)” my brother called me “bhai” so I knew I was like him, a boy” (IDI_Nepali Congress_2).

Physical Differences as well as appearances also separate the genders, which are “god given.”

“I saw with my eyes, the way that we look is very different. The way we walk, talk, appearance. I saw that women wore phulis (nose rings) and tika (forward ornament), and had long hair, and that their body parts grew differently, softer. I saw and observed these differences and decided that I was not a girl, but a man.” (IDI_Nepali Congress_1).

“After I was 16-17 years old, I learned that women were of “uthpadan shristi (Production origin) from my teachers and older sisters, they could get pregnant, give birth, and raise babies” (IDI_RPP_6)

The Unequal Division of Household Labor differentiates women from men and constructs women as weak and soft and men as strong and powerful.

“Girls, they did house work, like sweeping and cooking. As a man, we went out into the woods, went to graze the animals, went to school that was farther away from our house, this was not the way of the girls.”(IDI_Communist Party of Nepal_4).

“I thought that men could do anything and had more power – “mero didi haru lay mero kura manuparthiyo, hamilai khana banauno parthiyo (My sisters had to listen to us brothers, they had to make us food.” (IDI_Nepali Congress_2)

“I knew that nari sobhav – kaam hundoraicha (women nature was less weak) because I saw that they could not do the tough things, could not withstand when someone yelled at them, could not defend themselves when they are getting yelled at and often cried. (IDI_Communist Party of Nepal__4).

Construction of Men’s Belief on Supremacy (physical, mental, and emotional) because they were allowed to work and play far away from home

“The “garo garo (hard)” work was given to me and my brothers and my sisters were given work that was “easier”. If we had to go to the bazzar (market) then the brothers would go, if it was household chores, “bansay ko kaam (kitchen work)” “baba ama sanga kam (work with my parents)” then my sisters used to do it.” (IDI_Nepali Congress_2).

“I thought that women were given house work because it was easier and it was safer for them. And that men were stronger and braver so we were allowed to be outside.” (IDI_RPP_6)

“Our “sanskriti (our traditions), our “parampara (rituals)” say that man is more, they have more responsibility and status in society. I think that women feel a sense of relief and less responsibility when men are around.”(Group 1_Nepali Congress)

Gender inequality is Reinforced and Sustained through Differences in Societies Perception, Expectation, and Regulation between the sexes serve as a structural inequality framework

“In my house, we never let the women – mother, older sister, younger sister, or any female – out of the house alone or to far away places bc we were always worried about their safety and we were worried about what society would think. The family was worried about “sanskar (traditions)” and what it would say about this daughter who left the house too much, and how that would look later for marriage.”(IDI_Communist Party of Nepal_4)

Men also use specific language which denotes women as property. In reference to a attractive women riding in a public vehicle, a passing driver in another vehicle exclaims to the driver “ahmama , yesto maal paish ( Wow, a sexy thing like that)?”.

“Some things boys can talk about like talking about girls we laugh and say its normal but if girls said that then they would be considered “Uttaulo (loose women)”. I have heard my family talk about “uttaulo” girls when they are seen talking too much or beyond what is appropriate but never about boys. I think this is due to our traditions and the our society.”(IDI_Nepali Congress_1)

In all of the observations, men are the only passengers observed using obscene language like “maha sale ( mother fucker)” and “Randi ko chora ( son of a bitch)”. Upon hearing these words, female passengers look disturbed and afraid, they visually shift away or turn their bodies away from these men. In one instance where men are confronted and criticized about their use of obscene language they respond “ K bholayko xa? Jasto manlakcha, test tai (What have I said? Whatever I want to say I can”.)

Schools serve as Primary Grounds for Reinforcing Gender roles, Inequality, and Stereotypes, starting with separation.

“I did not know why boys and girls were separate but I knew that we were not supposed to talk to, touch, or really interact with girls.” (IDI_Nepali Congress_1).

“We (Boys and girls) were separated so we never saw them. But sometimes we interacted, and during this time, when the girls came we would tease them – “hami seeti bajaun thiyo (we would blow whistle when we saw them)” and “ekdam chalkhayl hundiyo (we were very restless and rowdy to see the girls).” (IDI_Nepali Congress_2)

Schools, both at lower (high school) and higher (college) levels, and society Normalizes the Teasing of Girls as a Rite of Passage for Males as Entertainment.

“I used to tease girls, and I think that in college age, this is very normal and the way youths develop. Especially, in our college it was located in the bazzar (market) area so when we were allowed to wear outdress which was on fridays, all the other college male friends used to come to see our female friends. “malai ramilo lagthiyo.” (IDI_NepaliCongress_1)

During public transportation ride, a young male conductor stares and teases a attractive female passenger as she boards the vehicle, the older male driver notices the interaction, laughs, and shouts “ Oho, tero pani taruni jiskauna bela bhaisakiyo hai ( Oh wow, you are already at that age to tease women huh)?” Conductor laughs in response and says “ malai pani jiskauna auuxa ni ( Yes, even I have learned how to tease)”.

Teachers, Family, and other Society members serve as critical agents who normalize discrimination against women when one participant questioned the low number of female students and high number of early marriages, he was told

“chori ko jat bhia garayra jana jat ho kancha (Daughters caste are the type to get married and send away, my dear) and nobody else educates their daughter so why should we? After this, I accepted it and took it as a fact of life” (IDI_RPP_6)

School curriculum and extracurricular separated based on gender reinforce gender roles, and stereotypes which construct perception of girls with less capabilities than boys

“While there were probably equal amounts of students in the school, there were only male students who rose up as political leaders in the student protest for fee hike. Girls did not seem to want to participate. They used to complain about their studies getting disturbed, as well as being late to get home. Girls were only concentrated in their studies. They were not concerned about “das ko pariberthan (improving our country)” while “keta haru lai das ko pariberthan pani garnu parche jasto lagthiyo (boys were concerned with improving the country, doing work for the country.”(IDI_Nepali Congress_2)

“When I was in high school, I was put into Home science by my head teacher, I did not want to first because it was a “girls subject” but I had to go. There were only 9 boys in the class and all other girls. The girls also teased us and laughed and asked why we were in a girls class, I was ashamed myself.” (IDI_Communist Party of Nepal_4)

Men Believe women are incapable of taking a public position because of their “Inherent Differences”

“Purus ani istri (men and women) are different in almost everything. Like I said from the physical to our capabilities, to our worldly responsibilities. This is not a bad or “unequal” thing. This is simply different things which should not be taken as “bad or “good” they just simply are and they are set so this world can continue to work; women become pregnant, they give birth to and raise children, take care of the house while men take care of the family financially, and lead to improve society.” (IDI_Communist Party of Nepal _5).

“When we think of “Purus (man)”, we imagine a certain distinct status that nature or god has given us. Women also have some special characteristics that god or nature has given them that men do not hold. Even though men and women are “ two wheels of the same bike” they have different characteristics which are special to them.” (Group 1_NCP)

“It is fine to see women politicians but only, if they have taken care of their house duties, raised their children efficiently. I don’t think it is good if her house is a mess, if her children are running wild, if her house is not taken care of then she should not be running around outside.” (IDI_Communist Party of Nepal_5)

“You see, Maila haro ko surumai ant hudaina ( Women are never courageous to start anything) We have 33% women members in the trade union, and women hold lower level leadership positions, but they dont have “ant (courage)” to ever apply for the president positions, to be a president you need “ant” and they do not have it, otherwise what is stopping them?” (IDI_Nepali Congress_2)

Most of the participants believe that “we have already achieved 90% gender equality in Nepal with a small percent of inequality left”.

“We have achieved equality as you can see legislatively with the 33% quota, and in terms of legality, there are lots of rules protecting women. Honestly, there isn’t a lot of things left in terms of inequality. I do not think that gender equality needs to be specially paid attention to anymore or be a political issue anymore.” (IDI_Nepali Congress_2)

“I think that 25% is not equal because of uneducation, unawareness, poverty and also because men are “gamandi (proud)” and “murkha (idiot).” (IDI_RPP_6)

“I think that we are already equal but with different responsibilities. Women have household responsibilities and men outside, I think if we fulfill our different responsibilities then we can live in a equal society, especially now that we have equality in education and property rights.” (IDI_Communist Party of Nepal_5)

“In terms of society, there has been lots of “Paribatan (progress)” in these last 10 years. I think that there will always be differences in our social status and value due to our fundamental differences in the way we were created. Our “Bhouthik (fundamental)” differences has designated males with more roles, responsibilities, and status.” (Group 1_NCP).

Objective 2: Explore the relationship of men’s attitudes, perception, and behavior regarding gender-based violence: Menstrual Restriction (MR) and Rape

Most common age of learning about Menstrual Restriction is 6-13, ranging from a young child at age 6 to oldest at age 13.Most common age of learning about Menstruation function and meaning is later at 16-18 years older with higher education.Men initially understand Menstruation as a “Girls Things” where they are “ Xunuhudaina (Untouchable)” through observations of menstrual restriction practices in the home.

“I did not really know what it was, I was 8 – I just knew that girls had this restriction and that they could not cook for me. I knew that they were “ separate”, and “ different” but did not know what menstruating was.” (IDI_NepaliCongress_1)

“I was 6, when I first started noticing that my mother would not cook for a week every month and I would first argue with her and tell her to cook and she would say that she couldn’t touch the food. I did not really understand but I did not really ask. I honestly thought that my father had yelled at her so she was sitting separately.” (IDI_Communist Party of Nepal_4)

Men’s primary understanding of menstruation after school at 17-20 years is one of a natural, biological process which women go through in their bodies, a symbol of maturity/ ability to be pregnant, and a Expulsion of “fohori” dirty blood leaving a woman’s body.

“I learned it was some sort of a system that god has given women where blood collects and when they are on their period it breaks and the women have a period every month. I also understand it to be something that signals not being pregnant but the ability to be pregnant.” (IDI_RPP_6)

Although all participants report they do not believe in menstruation restriction practices and would like to abolish it, they reported to still follow practices due to traditions, fear of social exclusion, and family members

“I would tell my wife to cook for me too but my mother lives with us and I don’t want to make hersad so due to circumstances she does not cook for me. My wife and I both agree that this is a normal thing that does not need to be restricted but i do not talk about it with my parents, they will be sad that their son is breaking traditions” (IDI_Nepali Congress_1)

“My family does not listen to me. I often tell her to stop all of these restrictions but she does not want to leave her parampara. It is due to the print on her brain from our parampara and sanskar. (IDI_Communist Party of NepalL_4)

Majority participants report they did not know why MR took place. Some thought it was due to sanitary reasons to avoid blood leakage, while others did not question the reasons but took it as a fact of life and culture.

Since the elders of my family followed the traditions, and my neighbors follow the traditions, then I just thought it was a way of life. I think that we have to follow society bc society is the biggest thing like popular Nepali saying “jtay hawa tatai bagnuparxa – you have to flow where the wind is flowing”. (IDI_Communist Party of Nepal_5)

“MR practices are per our rituals and our sanskriti so we must follow them. Nothing will really happen if we don’t….BUT we must and we should follow our sanskar. This does not mean that we should blindly follow Chhaupadi or something like go and live somewhere else or live in animal goats. We at least have that much improvement.” (Group 1_NCP)

The majority of men in our sample did not believe that menstrual restriction is a critical issue adversely affecting society

“I do not think that this is a political issue, this is a “parampara (culture)” that will slowly end by itself – “testo khas issue hoina (It’s not a super important issue)” it’s not like the far west where there is chhaupadi, at least here, in the city the women are sleeping in the same room even if isolated.” (IDI_Nepali Congress_2)

“In cities it is not really a problem but still it exists in the Brawhan/chetri societies. Especially this is prevalent in the villages and they are isolated outside their house into huts which are susceptible to snakes, animals, and danger of violence.” (IDI_Communist Party of Nepal_5)

Only the Nepal communist manifesto mentions specific provisions against discrimination against menstruation. Furthermore, almost all men share a belief that this is a women’s only issue and responsibility which is created, followed, and sustained by women

“purus ko kai haath xaina ( men have no hand in this issue.) Honestly women have taken this MR as some sort of a right. This was started by women and can only end by women.” (IDI_NepaliCongress_2)

“This is a “ama-chori = mother-daughter” talk because this is a “laag-manu parne subject (subject they should be ashamed of)” so daughters and women don’t talk about it with us.” (Group 1_NCP)

The majority of men in our sample had initial exposure to observed rape in their late teens to early adulthood age, from 17-22 years old although many recall earlier incidents which would fall under rape but were not defined as such and there were no media outlets for news to spread. They define rape as “jabarjasti ( without consent)” sexual act.

“I think that rape used to happen before but not at the rate it happens now, and before if someone raped someone then they used to marry them immediately by putting sindoor on the women so they would be their wife.” (IDI_Communist Party of Nepal _5)

All participant believe that rape is primarily caused by unreciprocated, uncontrollable sexual urges, often provoked by women’s clothing, and behavior

“Rape is popular mostly around 15-16 to 20-15 which is when they are at a “chancal (restless)” stage or “khishor aauas” (teenage) which is when they have sexual urges and they cannot control” (IDI_Nepali Congress_1)

“When someone is beautiful, we often will look at them once, then want to look at them again so when some girls wear “ uthaulo (revealing)” clothing then they influence men’s thinking and their actions.” (IDI_Communist Party of Nepal _4)

“Why else do you think rape does not happen or occurs in very small cases in countries such as Saudi Arabia where the women are covered from head to toe? The way that women’s bodies look in certain clothes heavily influences a man’s thoughts and can provoke these thoughts and actions and people with wrong intentions can be born from it.” (IDI_NepaliCongress_2)

Men also believe that rape cases between “of sexual age” men and women happen only after women give some type of “hint”:

“Women have a big effect on men. Women always give men hints, they should not give these hints like: they should not talk to, keep relations with men they do not know, or talk to strangers in FB, go on dates, take car/motorcycle rides. Women have to protect themselves.” (IDI_NepaliCommUML_5)

“Kati lai kai nai kai aayo, bhau dakhako huncha, rape huna lai (Girls give some kind of hint before rape happens, you can tell by some part of the body).” Then the man takes the hint and acts aggressively on it.” (IDI_NepaliCommUML_4)

Some men believe that rape is more than sexual urges and is connected to power and vengeance.

“Rape is when one is exacting revenge, showing their power over someone, either political vengeance, or personal feelings. If it was a boy they would beat him but if it’s a girl, or if the revenge is taken through the women then the rape”

(IDI_Communist Party of Nepal _5)

Others believed that it is caused by mental illness, or “evil” individual choice which can be provoked by alcohol and drug use

“lots of alcohol and drug usages messes with their mind and cannot figure out difference between right and wrong so then they want to do wrong things. And they would prefer to do wrong thing, their heart becomes mischievous.” (IDI_NepaliCongress_2)

“In the case of child and elderly rape, the person clearly no longer knows the right from wrong, so they have crossed normal society bounds and have gone crazy” (Group_1_NCP)

All participants believe that prevention and elimination of rape is primarily through sexual education, stronger government laws and enforcement with heavy emphasis on individual level prevention and responsibility of safety

“we need heavy sex education, esp in the 8-12 classes which is the age range of most people committing these crimes. We should teach our youths about sex, health, about consent, about violence against women.” (IDI_Nepali Congress_1)

“The laws have to be stricter and people have to be scared of raping. There is also lots of corruption which need to be fixed where we do not let convicted rapist come out of jail or use their network for release of jail time.” (IDI_Nepali Congress_2)

“afno ijat safe rakh nu parcha ( we have to keep our dignity safe ourself)” (IDI_Communist Party of Nepal_4)

All participants claim there is absolutely no present connection between menstrual restriction and rape. The majority believe that MR is a “natural” tradition which is not violent in the ways that rape is

“MR is a natural, “parampar thing” which was passed down by our culture but rape is not a natural thing and should never happen – it is also not passed down by culture” (IDI_Nepali Congress_2)

“MR is a system in which if women would just follow the system it would not be hard. But rape is not a system, even animals don’t do that.” (IDI_Communist Party of Nepal_5)

Conclusion

The problems mentioned are not restricted to Nepal, and are part of a general problem with menstrual practices, as demonstrated by Hennegan [9].

Education of all involved groups, including families and young adults of both genders on reproductive health has been seen as crucial need by many authors [10,11] and has been a key recommendation as a result of our research as perceptions and health belief models are shaped early and peer groups and parents play an important role in this process. MR is as rape a necessary focus of future violence prevention strategies especially in Nepal [12].

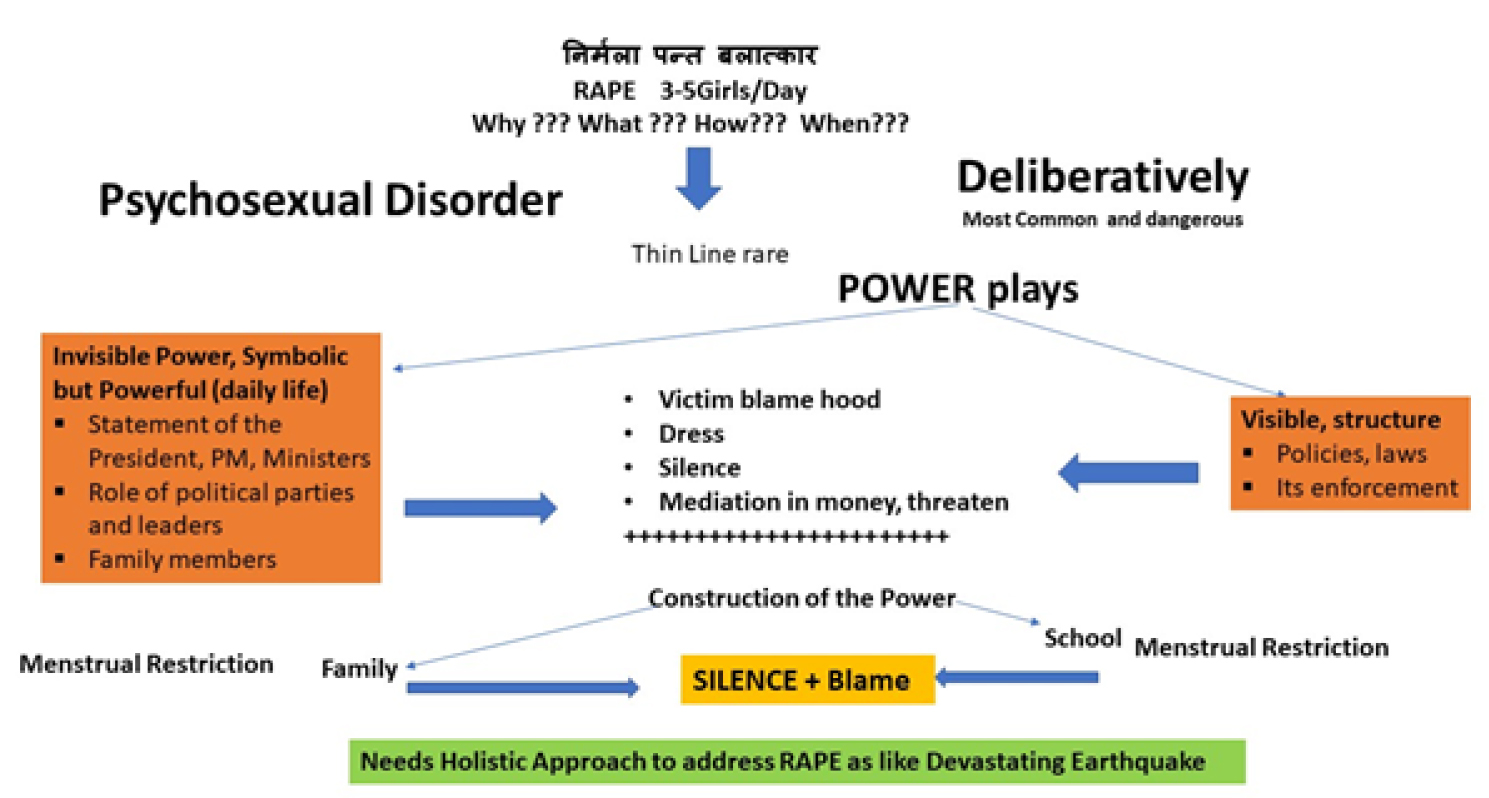

Figure 1. Construction of Visible and Invisible Power and Relationship between Menstrual Restriction and Rape.

Summary of recommendations based on project results

1. Home

- Reconstruct the language, behavior, division of labor, and other family dynamics inside the home for gender equality and human rights.

- Abolish any bias division of household labor

- Parents lead by example by sharing all household duty, abolish “kitchen/cleaning work as women’s work” and outside work as a mans

- Create new division of chores within your household which breaks stereotypical division of work and propels gender inequality

- Abolish any menstrual restriction practice at home

- Men should advocate for elimination of any restriction practices at home and eeducate self and other family members about menstruation, especially male family members

- Women should reject menstruation restriction practices at home

- Educate self (if needed) and other family members about menstruation, focusing on younger members, teaching girls to self-advocate and menstruate with dignity and boys to advocate for girls dignity and respect menstruation

- Change rules and regulations inside the home to reflect equal ideals

- Apply same restrictions apply to both male and female members e.g. time to come home, how far one can go outside the home

- Abolish imposing gender rules and norms regarding appearance on family members

- Allow girls and boys to choose their appearance and apparel according to their choice not their gender

- Girls can have short hair/not wear dresses/not have phulies (nose ring)

2. School

- Revise school curriculum and activities to institutionalize gender equality and human rights e.g. holding teachers and school staff accountable as gender equality role models

- Create enabling environment for dignified menstruation

- Reinforce gender equality and human rights by organizing series of extracurricular activities including parents and students

3. Political Parties/Leader

- Demonstrate as accountable state agents who propel gender equality and human rights as they committed in their political manifesto e.g. eeducate within the political party about gender equality, human rights, menstrual restriction, gender-based violence, and holding accountability at personal and party level.

- Regardless of their political party/power, support victims and stand against any violence against women and men

4. NGO

- NGOs demonstrate downward and upward accountability and role model for gender equality and human rights e.g. create zero tolerance for discrimination against gender

- Demonstrate as a champion for dignified menstruation

- Act as impartial agent for justice

- Create strong network with local government to connect communities with government for open access to resources

5. MEDIA

- Play as critical agent to transform gender norms, roles, and stereotypes e.g. take primary imitative to educate and empower public about gender equality and human rights, especially the impact of menstrual restriction on gender-based violence and dignity

6. STATE

- Bharatpur metro municipality guarantee the safety, security of each individual e.g. transparency of roles, mechanisms, and activities for justice committee

- Ensure access to justice committee including vice mayor

- Create direct mechanism to access resources and services especially for victims

- Establish hotline for victims of violence to access services

- Education appears to be the most important of these factors

References

- http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/ download?doi=10.1.1.866.5866&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1865/Men_VAW_report_Feb2015_Final.pdf

- https://nepal.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/ICRW.pdf

- The United Nations (1988) Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. Treaty Series 1249: 13.

- Ranabhat C, Kim CB, Choi EH, Aryal A, Park MB, et al. (2015) Chhaupadi Culture and Reproductive Health of Women in Nepal. Asia Pac J Public Health 27: 785–795.

- Dahal K (2008) Nepalese woman dies after banishment to shed during menstruation BMJ 337: 2520.

- Atreya A, Nepal S (2019) Menstrual exile – a cultural punishment for Nepalese women. Med Leg J 87: 12–13.

- Cardoso LF, Clark CJ, Rivers K, Ferguson G, Shrestha B, et al. (2018) Menstrual restriction prevalence and association with intimate partner violence among Nepali women. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2018.

- Hennegan J, Shannon AK, Rubli J, Schwab KJ, Melendez-Torres GJ (2019) Women’s and girls’ experiences of menstruation in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis. PLoS Med 16: 1002803.

- Sah AK, Shrestha N, Joshi P, Lakha R, Shrestha S, et al. (2018) Association of parental methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T gene polymorphism in couples with unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss. BMC Res Notes 11: 233.

- Sharma M, Gupta S (2003) Menstrual pattern and abnormalities in the high school girls of Dharan: a cross sectional study in two boarding schools. Nepal Med Coll J 5: 34–36.

- Thapa B, Powell J, Yi J, McGee J, Landis J, et al. (2017) Adolescent Health Risk and Behavior Survey: A School Based Survey in Central Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 15: 301–307.