Abstract

Human trafficking (HT) is a federal and international crime and is regarded as one of the most pressing human rights issues. Adult and minor victims are trafficked by force (rape, beatings, confinement), fraud, and coercion resulting in profound physical and psychological injuries; Department of Homeland Security; Vera Institute of Justice. Most clinicians fail to recognize HT victims. This policy brief’s purpose is to provide health care providers with a validated HT screening tool and best practice guidelines and recommendations to aid in victim identification. The strategies outlined are those published by the Vera Institute of Justice’s HT Victim Identification Tool and are endorsed by the Emergency Nurses Association and the International Association of Forensic Nurses. These proposals will increase the likelihood that patients experiencing sexual and labor exploitation will be identified.

Keywords

Human trafficking, Sexual exploitation, Forced labor, Human trafficking screening protocol, Human trafficking policy, Homelessness, Migrants, Runaways, Adults, Children

Screening for Human Trafficking: Best Practice Guidelines and Recommendations for Health Care Providers

Research has shown that human trafficking victims are not recognized by health care providers during their captivity [1-7]. Early identification of human trafficking victims is critical because the average life expectancy of a patient who is either sexually exploited or forced into labor is seven years [6]. A validated screening tool and assessment guideline would reliably identify adult and minor victims of both sex and labor trafficking [1-5,7,8-11].

Background and Scope of the Problem

Human trafficking is a federal and international crime and is commonly regarded as one of the most pressing human rights issues of our time. Adult and minor victims are trafficked by force (rape, beatings, confinement), fraud, and coercion (Department of Homeland Security) [12]. Children are particularly vulnerable to predators on the Internet via websites and social media and by mobile devices (United States Department of Justice, 2020) [13-15]. According to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, the number of suspected child-trafficking reports from 2010 to 2015 increased by 846 percent [16].

Prevalence

Globally, sexual exploitation makes up 79 percent of all cases, and forced labor accounts for 18 percent (United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime, 2020) [17]. Human trafficking affects every United States community, regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, and socio-economic background (National Human Trafficking Hotline, 2020) [18-23]. The average American age at the time trafficking began for sex trafficking is 17 years old, for labor is 22 years old (Polaris Project, 2020) [24], 15,222 females, 3,003 males, 135 gender minorities, and 3,966 of unknown gender were victimized. In that same year, there were 1,388 United States citizens/lawful permanent residents, 4,601 foreign nationals, and 16,337 of unknown nationality were identified as victims (Polaris Project, 2020) [24]. In 2019, there were eight trafficking cases in this southwestern state, ranking it 23rd in the nation for active cases; nationwide, there were 606 cases (The Human Trafficking Institute, 2019) [25].

Health and Social Impacts of Trafficking

There is compelling evidence of the health and social impacts of trafficking [1,3,5,7,9,10,26]. Reduced life expectancy was listed (Patient Safety Monitor Journal, 2017) [6], as was severe violent behavior [9]. Urinary tract infections, pelvic or abdominal pain, suicide attempts, and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures were highlighted [1,2] named life-threatening injuries and neglected health conditions (p. 282). Stevens & Dinkle [7] referenced serious health conditions such as “anxiety, depression, aggression, major depression, sleep disorders, suicidal ideation, substance use disorders and addiction” (p. e1). Domestic servitude and violence are included [3,10] identified “chronic medical problems, significant mental health issues, substance abuse/ misuse, reproductive or sexual health problems, diminished quality of life, and trauma” (p. 175). Involvement in the justice and foster care systems, running away, and being kicked out of home were listed [5]. Victims also developed posttraumatic stress disorder [7,26].

Human Trafficking Laws

The United States federal law on child sex trafficking [15] makes it a federal crime to “knowingly recruit, entice, harbor, transport, provide, obtain, or maintain a minor and cause that child to engage in any kind of sexual activity in exchange for anything of value” (para. 1). Child Protection Services must be alerted as required by law [1]. There are child abuse laws [1]. The law specifies that there are no child prostitutes [8]. Child soldiering, debt bondage, and bonded labor are unlawful [1,2]. Child Protection Services must be alerted as required by law [1]. Federal law requests HT training for health care providers [2]. Low HT detection results from ineffective laws [2]. Child soldiering, debt bondage, and bonded labor are unlawful [2]. There are mandatory reporting laws and safe harbor laws [2,10,26]. Surprisingly, federal law does not require proof that a defendant used force, fraud, or coercion to determine the action of trafficking when the victim is a minor [3].

Problem Identification and Understanding

McDow and Dols [4] define human trafficking as the use of force, fraud, or coercion by a trafficker to exploit a vulnerable individual to perform commercial sex or labor (p. e1). Each year between 600,000 and 800,000 men, women, and children are trafficked across international borders worldwide, and between 14,500 and 17,500 are trafficked into the United States (United States Department of State [27].

There is strong evidence health care providers do not recognize victims during their captivity [1-7,28]. Providers are often unfamiliar with human trafficking signs and symptoms [1,2,10]. Estimates are that 87-80 percent of human trafficking victims are seen by a health care provider while under the control of their trafficker [1,2]. Fifty-seven percent of female victims were not identified [4]. Thirteen percent of adult and child victims were recognized. Only nineteen percent of children were screened and referred to authorities [5]. Youth experiencing human trafficking interact with the healthcare and social services systems where they can be but are often not identified [5].

Because of their obligation to promote the well-being of patients, health care providers have an ethical obligation to take appropriate action to avert the harms caused by human trafficking that includes mandatory reporting to remain compliant with state law (New Mexico Department of Health [29]. By following evidence-based practice, health care providers should be compliant with state and federal laws because each patient identified as a human trafficking victim will be reported to agency and city police departments.

At-Risk Populations

Evidence has identified risk factors that contribute to patients’ vulnerability for human trafficking.

Children and Teenagers

Risk factors for children and teenagers becoming victims include “being a runaway, possessing developmental delays, teens identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer or questioning (LGBTQ), those who commute to school alone, are hungry or malnourished, are poor, come from dysfunctional families, experience emotional distress, have mental illness, and abuse substances” [1,2,5,6,9,28,30]. Young girls are targeted [3,4,28]. Youth who are at risk for abuse or violence are often targeted [2,28,31]. Adolescents involved in foster care or juvenile justice systems, who were unstably housed or homeless, involved with child protective services or had a negative interaction with law enforcement were also more likely to become victims [1,4,5,28,30,32]. Finally, younger victims are often connected to gangs or are migrants [9,10,28,33].

Females

Most victims of human trafficking are young women and girls [1,3,4,9,28] found that “nearly 70 to 80 percent of trafficking victims are women and girls, and 97 percent of those are trafficked for sexual exploitation” (p. 830). Egyud et al. (2017) [1] ranked the percent of female trafficking victims at 90 percent (p. 527). Greenbaum and Bodrick [34,35] state that globally, between January 2008 and June 2010, human trafficking taskforces discovered that 94 percent of sex trafficking victims were female (p. 2). Young women are at the greatest risk for sexual exploitation and are treated for “unplanned pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, and traumatic injuries” [4]. They seek out health care providers for reproductive health issues such as miscarriages and to perform abortions or to secure birth control [36]. As a result, “Health care providers who work in women’s health services have a unique opportunity to identify and intervene in the human trafficking operation due to their heightened level of contact with the victims” [36]. In 2018, the National Human Trafficking Hotline- 18] identified over 15,000 female victims [4].

Migrants

Migrant individuals are easy targets for domestic servitude because they are cheap labor, and their abusers face low risk of prosecution [3,5,8,10,33]. Mexican indigenous women are especially vulnerable due to “structural poverty, marginalization, social exclusion, and a traditional[ly] patriarchal culture” [28,33]. Elderly migrant family members are targeted for access to their benefits [3].

Consequences of Human Trafficking

Victims of human trafficking often have “multiple sexually transmitted infections and abortions, poor dental hygiene, and severe or recurring head and neck trauma from forced oral sex” [6,28,30,33]. They develop somatization, immunosuppression, inflammation, headaches, dizzy spells, exhaustion, back pain, memory problems, unintentional weight loss, nausea, indigestion, cancer, heart disease, high cholesterol, asthma, and gastrointestinal, muscular, and neurological symptoms [37]. Trafficked children and adults can develop complex posttraumatic stress disorder [26,31,38]. Victims, regardless of age, can have an increased risk for “anxiety disorders, Stockholm syndrome, major depressive disorder, substance abuse, self-harm, and suicide ideation” [30,31,33]. Traffickers often force drugs on victims as a means of control and exploitation [28,39].

Understanding Healthcare Workers and First Responders’ Roles

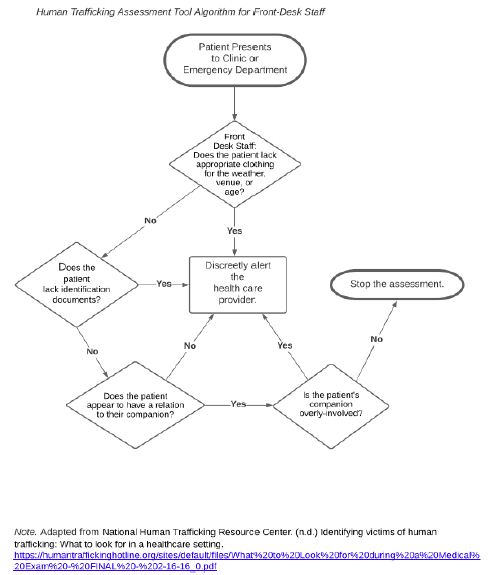

This policy brief follows a multidisciplinary approach and follows the Vera Institute of Justice-[40]’s Trafficking Victim Identification Tool (TVIT). The TVIT has been developed based on the latest research and best practices. It was designed for use by behavioral health, health care, social work, and public health professionals. The tool is a reliable, brief screen com1monly used in public health, health care, behavioral health, and social service settings. “The TVIT has been found to be valid and reliable in identifying victims of sex and labor” [8,40]. It is a statistically validated screening tool that encompasses both labor and sex trafficking, adult and child victims, and foreign nationals and United States citizens. It is available in long- and short-form. The tool is also available in Spanish” (National Human Trafficking Hotline, n.d., para. 1)-[18]. If the health care provider believes the patient is a human trafficking victim, they should follow agency policy and file a human trafficking report with the agency and city’s police departments (Vera Institute of Justice [40]. First, front desk staff will discreetly alert the provider if a patient screens positive for any red flags or indicators listed in the National Human Trafficking Resource Center’s (NHTRC) “What to Look for in a Healthcare Setting” (see Table 1, p. 34; Figure 1, p. 45). Examples of red flags or indicators are if a patient does not have a permanent address, if a patient does not appear to have a relation to the person accompanying them, or if a patient’s body language and communication style or those of the partner are combative or abusive [7,10,34,40].

Table 1: Human Trafficking Assessment Tool, Table of Steps for Front Desk Staff

| 1) Patient presents to clinic or emergency department. Go to step 2. |

| 2) Front-desk staff check-in patient while discreetly screen for red flags and indicators listed in the Vera Institute of Justice’s Trafficking Victim Identification Tool by completing the following steps. Go to step 3. |

| 3) Does the patient lack appropriate clothing for the weather, venue, or age? If yes or no, go to step 4. |

| 4) Does the patient lack identification documents? If yes or no, go to step 5. |

| 5) Does the patient appear to have a relation to the person accompanying them?If yes or no, go to step 6. |

| 6) Is the patient’s companion overly involved (does not let the patient speak for themselves, refuses to let the patient have privacy, or interprets for them)? If yes, go to step 7. If no, go to step 8. |

| 7) Discreetly alert the health care provider for further assessment. |

| 8) Stop the assessment. |

Note: Adapted from National Human Trafficking Resource Center. (n.d) Identifying victims of human trafficking: What to look for in a healthcare setting. http://surl.li/dshkj

Figure 1: Human trafficking assessment tool algorithm for front-desk staff

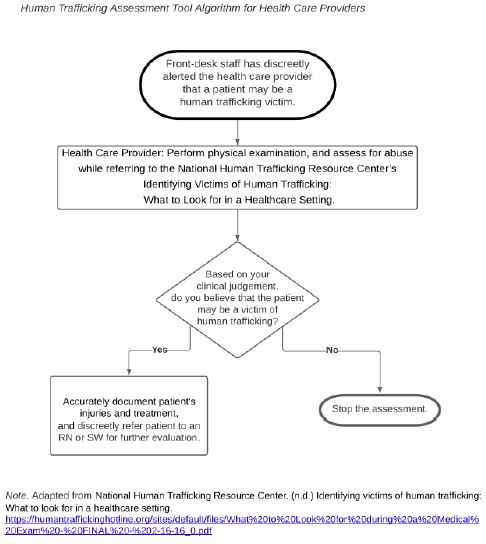

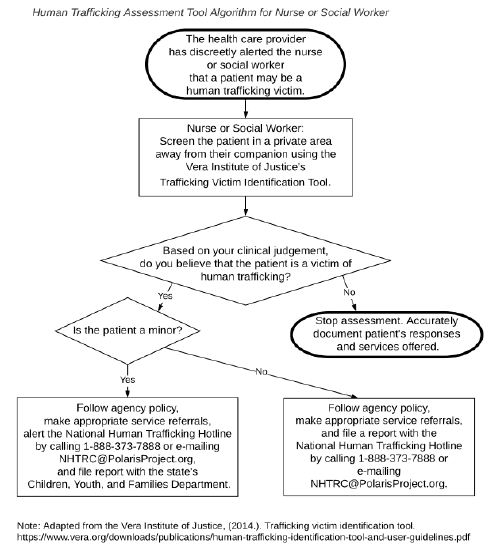

Second, the health care provider will assess the patient by using their own clinical judgment and by assessing for red flags and indicators listed on the NHTRC’s “What to Look for in a Healthcare Setting” (Figure 2 and Table 2) [40]. The NHTRC is referenced within the TVIT and provides a list of general indicators that clinicians may encounter during their assessments. The clinician’s verbiage should not expressly state “human trafficking” but should be generalized to avoid making the patient feel uncomfortable and alerting the patient’s companion (likely their trafficker). If the health care provider believes the patient may be a victim of human trafficking, the provider should discreetly refer the patient to a nurse or social worker for further assessment. Third, if criteria are met, a nurse or social worker should interview the patient in a private setting and out of sight of their companion [40]. The nurse or social worker should ask the victim a series of follow-up questions from the TVIT [8,10,40] (see Table 3, p. 35; Figure 3, p. 47). If the nurse or social worker believes the patient is a victim, and the patient is a minor, follow agency policy, make appropriate service referrals, alert the National Human Trafficking Hotline by calling 1-888-373-7888 or e-mailing NHTRC@PolarisProject.org, and file a report with the state’s Children, Youth, and Families Department as required by law [1] (see Table 3, p. 35; Figure 3, p. 47). If the nurse or social worker believes the patient is a victim, and the patient an adult, follow agency policy, make appropriate service referrals, and file a report with the National Human Trafficking Hotline [18] by calling 1-888-373-7888 or e-mailing NHTRC@PolarisProject.org (see Table 3, p. 35; Figure 3, p. 47).

Figure 2: Human trafficking assessment tool algorithm for health care providers

Table 2: Human Trafficking Assessment Tool, Table of Steps for Health Care Providers

| 1) Front-staff have discreetly alerted the health care provider about a possible human trafficking victim. Go to step 2. |

| 2) The health care provider will perform a thorough physical examination while assessing for psychological and physical abuse, traumatic experiences, chronic substance abuse, or violent physical and psychological assaults. The clinician will look for signs and symptoms of human trafficking abuse by utilizing the National Human Trafficking Resource Center’s Identifying Victims of Human Trafficking: What to Look for in a Healthcare Setting. Accurate document the patient’s treatment and services offered. Go to step 3. |

| 3) Based on the health care provider’s clinical judgement, does the health care provider believe that the patient may be a victim of human trafficking? If yes, go to step 4. If no, go to step 5. |

| 4) The health care provider should accurately document patient’s injuries and treatment, and discreetly refer patient to an RN or SW for further evaluation. |

| 5) Stop the assessment. |

Note: Adapted from National Human Trafficking Resource Center. (n.d) Identifying victims of human trafficking: What to look for in a healthcare setting. http://surl.li/dshkj

Table 3: Human Trafficking Assessment Tool, Table of Steps for Nurse or Social Worker

| 1) The health care provider has discreetly alerted the nurse or social worker about a possible human trafficking victim. Go to step 2. |

| 2) The nurse or social worker will discreetly conduct the Vera Institute of Justice’s Trafficking Victim Identification Tool in private, away from the patient’s companion. Go to step 3. |

| 3) Based on the nurse or social worker’s clinical judgement, does the nurse or social worker believe that the patient is a victim of human trafficking? If yes, go to step 4. If no, go to step 7. |

| 4) Is the patient a minor? If yes, go to step 5. If no, go to step 6. |

| 5) The nurse or social worker should follow agency policy, make appropriate service referrals, alert the National Human Trafficking Hotline by calling 1-888-373-7888 or e-mailing NHTRC@PolarisProject.org, and file report with the state’s Children, Youth, and Families Department. |

| 6) The nurse or social worker should follow agency policy, make appropriate service referrals, and file a report with the National Human Trafficking Hotline by calling 1-888-373-7888 or e-mailing NHTRC@PolarisProject.org. |

| 7) Stop the assessment. Accurately document patient findings and services rendered. |

Note: Adapted from Vera Institute of Justice. (2014). Screening for human trafficking: Guidelines for administering the trafficking victim identification tool. Vera Institute of Justice. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/sites/default/files/human-trafficking-identification-tool-and-user-guidelines.pdf

Figure 3: Human trafficking assessment tool algorithm for nurse or social worker

Impact and Significance

It is imperative that health care providers accurately document patients’ injuries and treatment and clearly distinguish between sexual exploitation or forced labor when reporting to law enforcement officers [41]. Studies have shown that police efforts mainly focus on sex trafficking cases instead of labor trafficking [42] Introduction section). In 2017, only 225 labor trafficking offenses were reported by police to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program, representing only 18 percent of the total reported human trafficking offenses reported [42], Introduction section). Law enforcement often has difficulty distinguishing labor trafficking victims from legitimate workers because they work in intermingled conditions [42], Challenge 1 section). Without evidence that the forced labor victims suffered physical abuse, “law enforcement officers are skeptical that prosecutors will accept domestic servitude cases” [42], Challenge 3 section). The Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 and the creation of the Civil Rights Division in the Department of Justice’s Human Trafficking Prosecution Unit within the Criminal Section in 2007 enables prosecutors to work with law enforcement agencies and attorneys to investigate human trafficking cases [30,36]. However, without the exchange of information between health care providers and law enforcement, efforts to identify and rescue human trafficking victims in the community is extremely limited [36]. Generally, victims who escape their traffickers seek assistance from and confide in health care providers instead of police [36]. There exists a gap in the connection between the two entities, which delays the early victim intervention and identification, often resulting in severe physical and mental injuries to victims [30,36]. Evidence suggests that health care providers should be trained by law enforcement officials assigned to a human trafficking task force [19] to ensure that clinicians recognize the warning signs that victims may present with, become familiar with intervention techniques, and understand how to deploy the task force’s protocols for rescue [36]. Collaborating efforts between law enforcement officers and health care providers can assist the human trafficking population. Because health care providers and victims have regular contact, if clinicians worked with law enforcement task forces, more victims could be identified and rescued [36]. Victims benefit from case management services from an interdisciplinary team. This joint approach provides comprehensive protection. Social workers can assist with connecting the patient with community resources for food, shelter, and clothing. Health care providers can render medical aid and provide hotline numbers for local anti-trafficking services such as the NHTRC [6,36]. Therapists can help the victim develop coping skills and reduce the symptoms of mental illness. Law enforcement officers who are trained in human trafficking can “identify the indicators of a human trafficking situation, secure evidence for subsequent prosecution, and refer victims to social service providers” [43].

Evidence Search Strategy, Results, and Evaluation

The search for current, 2016-2021, peer-reviewed articles which were published in academic journals was conducted via the University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences online library. These databases included Search University of St. Augustine (USA), PubMed, GALE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and Science Direct. Google Scholar was also utilized to locate open access articles. The following search terms were used to locate articles specific to this study: Human trafficking, sex trafficking, forced labor, human trafficking assessment tool, human trafficking algorithm, human trafficking assessment, human trafficking screening protocol, human trafficking policy, human rights, sexual exploitation, labor exploitation, domestic servitude, sex industry, commercial sex, trauma, United States, America, child welfare, homelessness, migrants, runaways, primary care providers, emergency department, health care providers, clinicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, legal nurse consultant, physician assistants, emergency room, emergency department, human trafficking persons, missing persons, adults, female, prostitutes, pimps, young adults, children, youth, adolescents, juveniles, and pediatrics. Variations of these terms were used to ensure detailed search results. The exclusion criterium was years prior to 2015. The results of the search yielded 21 research articles. One article dealt solely with sanctions and was eliminated from the selection. Several research articles were not of or related to America or the United States and were excluded.

Themes from Evidence Review

The main themes found in the literature were compared with national protocols, regulations, position statements, and accreditation standards. The literature included themes that human trafficking victims often go unrecognized by health care providers, staff lack human trafficking education, there is the need for a validated, reliable, and standardized human trafficking assessment tool, a multidisciplinary team approach is vital, and the law is explicit about human trafficking.

Human Trafficking Victims are not Recognized by Health Care Providers

A trend that was supported by the literature is that the use of a human trafficking assessment tool in the health care setting is necessary to help health care providers recognize victims of human trafficking. Leslie [2-5] and Stevens [7] concluded that health care providers are often the only professionals to interact with trafficking victims who are still in captivity, but these patients go unrecognized because clinicians do not assess for human trafficking (see Appendix A, pp. 49, 51-52, 54; Appendix B, pp. 57-58, 62, 65). Eighty-seven percent of victims were not recognized by their health care providers [1].

Staff Lack Human Trafficking Education

There were several recommendations for providing specialized human trafficking education to bridge the gap in staff knowledge and skills. Health providers and law enforcement officers are often unfamiliar with human trafficking signs and symptoms [10,36,42]. Results of the study reflect the need for formal education, screening, and treatment protocols for health care personnel and forensic investigators to guide the identification and rescue of victims of human trafficking [1,35,41]. Interviews revealed that the experience, approach, and content varied widely [44]. Potential improvements in current training approaches included standardization of training, metrics to evaluate and develop the evidence base for training impact, funding opportunities, survivor integration, and incentives to encourage training [44]. Providing education and screening tools improved recognition of trafficking victims and improved recognition of patients in other types of abusive situations, such as domestic violence and sexual assault [1] (see Appendix A, pp. 54-55; Appendix B, pp. 57-59, 62-63).

Need for a Validated Human Trafficking Assessment Tool

The most frequently cited intervention for identifying human trafficking victims was the use of a validated and standardized human trafficking assessment tool. Of the 14 descriptive non-experimental research articles of good quality, six resources agreed on recommendations to provide health care providers with a reliable and standardized assessment tool to improve recognition of trafficking victims by systematically detecting red flags and indicators [1,2,4,5,7,8,10,34,40] (see Appendix A, pp. 48-49, 52-54; Appendix B, pp. 60, 62-65). Both Leslie [2] and Powell, Dickins, and Stoklosa, [44] found that a validated and standardized method of screening increases the degree at patients experiencing sexual and labor exploitation will be identified (see Appendix A, pp. 52, 54; Appendix B, pp. 60, 63). Utilizing the TVIT to identify human trafficking victims ensures that key information is correctly and consistently provided to all health care providers [8,13,40].

Interprofessional Collaboration

Six articles examined the need for a multidisciplinary team approach [3,4,7,10,36,41] identified emergency room nurses, risk managers, and clinical educators (pp. 30-32). McDow & Dols (2020) [4] named “nurse managers, health care providers, ultrasound technicians, nursing assistants, and volunteers” (p. e1). Health care professionals and law enforcement officials should unite to identify and rescue victims [36]. Multidisciplinary teams should be educated to assist victims [10]. Stevens & Dinkle [7] identified administrators, technology teams, primary care providers, and staff as members of the interdisciplinary team (p. e2) (see Appendix A, pp. 50, 52, 54, 56; Appendix B, pp. 58, 60, 61).

The Law Is Explicit about Human Trafficking

Health care providers are required by this southern state’s Administrative Code NMAC 7.1.14 to call the ANE Hotline, 1-800-445-6242, that an incident of abuse, neglect, exploitation, suspicious injury, environmental hazard, or death has occurred (New Mexico Department of Health-[29], n.d.). Child Protection Services must be alerted as required by law [1]. There are child abuse laws [1]. The law specifies that there are no child prostitutes [8]. Child soldiering, debt bondage, and bonded labor are unlawful [1,2]. Child Protection Services must be alerted as required by law [1]. Federal law requests human trafficking training for health care providers [2]. Low human trafficking detection results from ineffective laws [2]. Child soldiering, debt bondage, and bonded labor are unlawful [2]. There are mandatory reporting laws and safe harbor laws [2,10,21,26]. Federal law does not require proof that a defendant used force, fraud, or coercion to determine the action of trafficking when the victim is a minor [3] (see Appendix A, pp. 48-51, 54-55; Appendix B, pp. 57-60, 62-64).

Best Practice Recommendations

A thorough review of the literature guided these evidence-based guidelines and recommendations to improve human trafficking practice for health care providers. Evidence from the literature proved that human trafficking victims often go unrecognized by health care providers. Based on the conclusions drawn from the evidence, the following practice recommendations are encouraged. 1) Health care providers should seek assistance from multidisciplinary teams comprised of front desk staff, nurses, health care providers, social workers, therapists, ultrasound technicians, nursing assistants, volunteers, and law enforcement. 2) The teams should be trained in human trafficking to keenly identify victims, assess victim needs, efficiently employ a victim-service delivery model, accurately document patient injuries and treatment, and report incidents of violence and victimization according to institutional policy, thereby allowing law enforcement to investigate allegations and rescue victims [41]. 3) Research established the need for a validated, reliable, and standardized human trafficking assessment tool, which would be useful for increasing the number of identified victims by health care providers who are knowledgeable about human trafficking red flags and victim indicators [1,2,4,5,7,8,10,40]. 4) Health care providers in this southwestern American state, because of their obligation to promote the well-being of patients, have an ethical obligation to take appropriate action to avert the harms caused by human trafficking that includes mandatory reporting to remain compliant with state law (New Mexico Department of Health [29].

Endorsements

These human trafficking evidence-based guidelines and recommendations are endorsed by the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA)-[45] and the International Association of Forensic Nurses (IAFN). In their joint human trafficking position statement, the ENA and IAFN support health care providers “appropriate education and training” about human trafficking, working collaboratively with community partners and criminal and civil justice systems, and reporting suspicions or behaviors as required by law (Emergency Nurses Association, 2018) [45]. In addition, the American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Statement on Global Human Trafficking and Child Victimization recommends that health care providers serving children be trained about human trafficking and its relation to immigration [34,35].

Conclusion

Human trafficking is a federal and international crime and is commonly regarded as one of the most pressing human rights issues of our time. Adult and minor victims are trafficked by force (rape, beatings, confinement), fraud, and coercion (Department of Homeland Security, 2020) [12]. Early identification of human trafficking victims by their health care providers is critical because the average life expectancy of a human trafficking victim is seven years [6]. To increase efficacy, research recommends that health care providers should be adequately trained and use a validated, reliable, and standardized human trafficking assessment tool such as the Vera Institute of Justice-[40]’s Trafficking Victim Identification Tool [8,10,40]. Health care providers should seek assistance from multidisciplinary teams that include law enforcement [4,36,40]. This practice will help streamline victim identification, assess victim needs, employ a victim-service delivery model, and report incidents of violence and victimization with efficiency. The purpose of this policy is to increase clinician human trafficking efficacy by introducing best practice guidelines and recommendations for health care providers [46-50].

References

- Egyud A, Stephens K, Swanson-Bierman B, DiCuccio M, Whiteman K (2017) Implementation of human trafficking education and treatment algorithm in the emergency department. Journal of Emergency Nursing 43: 526-531. [crossref]

- Leslie J (2018) Human trafficking: Clinical assessment guideline. Journal of Trauma Nursing, 25: 282-289. [crossref]

- Mason S (2018) Human trafficking: A primer for LNCs. Journal of Legal Nurse Consulting 29: 28-33.

- McDow J, Dols JD (2020) Implementation of a human trafficking screening protocol. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners.

- Mostajabian S, Santa Maria D, Wiemann C, Newlin E, Bocchini C (2019) Identifying sexual and labor exploitation among sheltered youth experiencing homelessness: A comparison of screening methods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16.

- Diagnosing human trafficking when a patient is a victim (2017) Patient Safety Monitor Journal.

- Stevens C, Dinkel S (2020) From awareness to action: Assessing for human trafficking in primary care. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners e1-e5.

- Chisolm-Straker M, Sze J, Einbond J, White J, Stoklosa H (2019) Screening for human trafficking among homeless young adults. Children and Youth Services Review 98: 72-79.

- Miccio-Fonseca LC (2017) Juvenile female sex traffickers. Aggression and Violent Behavi, 35: 26-32.

- Peck JL (2020) Human trafficking in the clinical setting: Critical competencies for family nurse practitioners. Advances in Family Practice Nursing 2: 169-186.

- Wilks L, Robichaux K, Russell M, Khawaja L, Siddiqui U (2021) Identification and screening of human trafficking victims. Psychiatric Annals 51: 364-368.

- Department of Homeland Security (2020) Human trafficking 101 information sheet.

- The United States Department of Justice. (n. d.) Department of Justice components.

- United States Department of Justice, 18 U.S.C § 1591 (2020) Sex trafficking of children or by force, fraud, or coercion.

- United States Department of Justice. (2020) Child sex trafficking.

- Prylinski KM (2020) Tech Trafficking: How the internet has transformed sex trafficking. The Journal of High Technology Law 20: 338-372.

- United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (2020) Global report on trafficking in persons.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline. (2020) Sex trafficking.

- Cook County Human Trafficking Task Force (2020) Human Trafficking Model Policy for Healthcare.

- Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children & Families Office on Trafficking Persons, Fact Sheet: Human Trafficking. (2021) Fact sheet: Human trafficking.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline (2011) Human trafficking assessment tool for educators.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline. (n.d.) Recognizing the signs.

- National Human Trafficking Resource Center. (n.d.) Identifying victims of human trafficking: What to look for in a healthcare setting.

- Polaris Project (2020) 2019 data report: The U.S. national human trafficking hotline.

- The Human Trafficking Institute (2019) 2019 federal human trafficking report: New Mexico state summary.

- Scott JT, Ingram AM, Nemer SL, Crowley DM (2019) Evidence‐based human trafficking policy: Opportunities to invest in trauma‐informed strategies. American Journal of Community Psychology 64: 348-358. [crossref]

- United States Department of State. (2004) Trafficking in Persons Report.

- Moore JL, Houck C, Hirway P, Barron CE, Goldberg AP (2020) Trafficking experiences and psychosocial features of domestic minor sex trafficking victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 35: 3148-3163. [crossref]

- New Mexico Department of Health. (2021) Abuse, Neglect, and Exploitation Reporting Guide, State Fiscal Year 2021.

- Roney, L. N., & Villano, C. E. (2020) Recognizing victims of a hidden crime: Human trafficking victims in your pediatric trauma bay. Journal of Trauma Nursing 27: 37-41. [crossref]

- Banu S, Saunders J, Conner C, Blassingame J, Shah AA (2021) Mental health consequences of human trafficking. Psychiatric Annals 51: 368-371.

- Miller AJ, Arnold-Clark J, Brown KW, Ackerman-Brimberg M, Guymon M (2020) Featured counter trafficking program: The law enforcement first responder protocol. Child Abuse & Neglect 100. [crossref]

- Acharya AK (2019) Prevalence of violence against indigenous women victims of human trafficking and its implications on physical injuries and disabilities in Monterrey city, Mexico. Health Care for Women International 40: 829-846. [crossref]

- Greenbaum J, Bodrick, N. (2017) Global human trafficking and child victimization. Pediatrics 140: 1-12. [crossref]

- Greenbaum J, Stoklosa H (2019) The healthcare response to human trafficking: A need for globally harmonized ICD codes. PLoS Medicine 16. [crossref]

- Helton M (2016) Human trafficking: How a joint task force between health care providers and law enforcement can assist with identifying victims and prosecuting traffickers. Health Matrix 26: 433-473. [crossref]

- Clay-Warner J, Edgemon TG, Okech D, Anarfi JK (2021) Violence predicts physical health consequences of human trafficking: Findings from a longitudinal study of labor trafficking in Ghana. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 279. [crossref]

- Ottisova L, Smith P, Oram S (2018) Psychological consequences of human trafficking: Complex posttraumatic stress disorder in trafficked children. Behavioral Medicine 44: 234-241. [crossref]

- Marburger K, Pickover S (2020) A comprehensive perspective on treating victims of human trafficking. The Professional Counselor 10: 13-24.

- Vera Institute of Justice (2014) Screening for human trafficking: Guidelines for administering the trafficking victim identification tool. Vera Institute of Justice.

- Nogalska AM, Henderson HM, Cho SJ, Lyon TD (2021) Police interviewing behaviors and commercially sexually exploited adolescents’ reluctance. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 27: 328-340.

- Farrell A, Bright K, de Vries I, Pfeffer R, Dank M (2020) Policing labor trafficking in the United States. Trends in Organized Crime, 23(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-019-09367-6

- Clawson HJ, Dutch N, Cummings M (December 2016) Law enforcement response to human trafficking and the implications for victims: Current practices and lessons learned. U.S. Department of Justice.

- Powell C, Dickins K, Stoklosa H (2017) Training US health care professionals on human trafficking: Where do we go from here?. Medical Education Online 22. [crossref]

- Emergency Nurses Association (2018) Joint position statement: Human trafficking awareness in the emergency care setting.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016) CDC’s policy analytical framework.

- Department of Veterans Affairs (2017) Veterans Health Administration’s Directive 1199.

- First Nations Community Healthcare (2021) Sex trafficking services.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine (2021) Johns Hopkins nursing evidence-based practice appendix C: Evidence level and quality guide.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine (2021) Johns Hopkins evidence-based practice model.