Abstract

A description of today’s financial disparities between the rich and the poor was fed to Idea Coach (AI) in the Mind Genomics platform (www.bimileap). Idea Coach was instructed to generate eight different ‘mind-sets’ of people based upon the description of the disparities, and to answer a variety of questions about these mind-sets. The eight mind-sets and their AI-generated features were fed to a second run of Idea Coach to generate slogans for a presidential campaign, assuming different factors, such as the year of the campaign, the nature of the person who would be the recipient of the slogan, etc. The exercise revealed the potential for deeper understanding of social issues, as well as the prospect of asking what-if questions in real time, low cost, for any topic that can be explicated simply and directly. The exercise further revealed the ability of AI to synthesize additional insights, returning all of the information in an Excel-formatted, easy-to-read ‘Idea Book.’ The process takes minutes for each iteration with the Idea Book combining all of the iterations from one run and returned to the user within a half hour.

Introduction

Economic disparities among people is a fact of life, and indeed often lies at the heart of major changes in society. The origin of this paper came from a life-long interest by the senior author, AK, in the seismic changes of society due to these economic inequalities, especially the inequality emerging today in the United States [1]. The popular term for the ultra-rich is the ‘1%’ [2]. Again and again, as the concentration of wealth increases, we end up seeing the somewhat discouraging charts showing how truly wealthy the 1% or more realistically the simply rich and ultra rich own, compared to everyone else. And, to make things worse, the stories become ever more heartbreaking as the conspicuous consumption of the ultra-rich is flaunted in the face of other people in lower socio-economic strata who have seen their lives damaged by inflation, their hopes for better economic lives buried under the insistent reduction of what they can afford and even what they can realistically attain. With this mournful issue stated, the notion was to understand the potential of artificial intelligence to help understand the mind-sets of people. Previous work by Moskowitz et. al., on the ‘fraying of America,’ looking at the responses of American a decade ago to different aspects of society suggested that people were not of one mind-set, but rather people differed among themselves in how they felt about the economic disparities. A decade later, with the foundation laid by the earlier work, two of the authors (AK and HM) decided to apply new tools afforded by AI to the mind of people presented with the story of the United States and its discouraging economic disparities.

The paper presented here is based upon the use of AI in an emerging science known as Mind Genomics [3,4]. Mind Genomics emerged as a way to understand the way people make decisions about the everyday. Rather than looking for general principles of behavior, principles which required artificial situations manipulated by an experimenter, Mind Genomics attempted to understand decision making by presenting people with vignettes, combinations of messages presenting ordinary acts of behavior in a topic area, such as voting (REF), or banking (REF), or even eating meals in a restaurant [5]. The output of these simple experiments was the ability to put numbers of different aspects of behavior to show how these aspects drove decisions, and then divide actual people into new to the world groups, mind-sets, based upon the similarities of the patterns of behavior that they evidenced for this simple, everyday task. These mind-sets often transcended countries, although the distribution of the same mind-set differed from country to country [6]. The discovery of mind-sets became a focus of many Mind Genomics studies. The approach was easy, the respondents had no problem evaluating different combinations of messages, and from the pattern of their ratings statistics had no problems first identifying the driving powers of the different messages, and then discovering the existence of meaningful mind-sets, groups of people with different ways of responding to the same messages.

The Introduction of AI to Mind Genomic Using Idea Coach, and Its Expansion to Scenarios

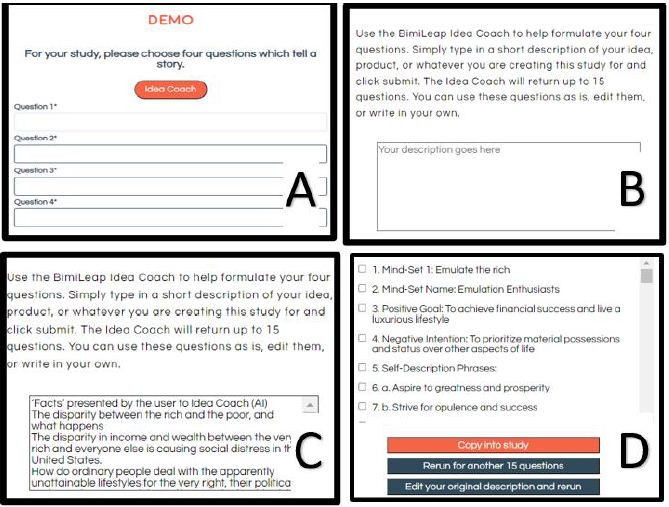

The underlying objective of the Mind Genomics process was that the user would achieve more knowledge by working at the level of the granular, rather than asking high level questions. The world of consumer research was overrun with surveys, most of which wanted top-line opinions of general topics, such as one’s opinion of the wait time in a doctor’s office, or the ease of purchasing a product, and the demeanor and sales behavior of the staff in a store. These general surveys ended up producing a great deal of score-card information about products and services, emerging indices like the Press Ganey score for medical services, and similar types of numbers [7]. What was not being provided from these scores was a deeper understanding of the experienced reality of the topic. The Mind Genomics effort emerged as a tool to understand the granular experience. All the users had to do was create combinations of messages, so called vignettes which were combinations of elements. The respondent would be exposed the vignettes, evaluate each vignette, and from the evaluation statistics such as regression and clustering would end up showing the strength of the elements (driving force) and mind-sets, as was noted above. There was only one issue which stopped Mind Genomics in its tracks in many cases. That was the fact that many prospective users ‘froze’ at the requirement to create questions which tell a story, and from those questions create four answers to each question. Answers were fairly easy to create, but questions were another thing entirely. Many users froze at the prospect of coming up with these questions, not realizing that the entire purpose of the questions was to create a structure bye which anyone could develop the necessary messages or elements to be used. By forcing the user to create the questions first, it was assumed that the user would be able to create the story through the questions, and then have little trouble providing the answers. The reality was that the prospect of having to ask questions and then to provide answers to those questions turned out to be more intimidating than one might have thought. The solution was not the extensive ‘training’ to teach people how to think, an effort which occasionally worked but more often than not ended in dismal failure. Rather, the solution emerged with the popular AI program, ChatGPT [8]. The Mind Genomics program, www.bimileap.com, was outfitted with the Idea Coach. Users could write in the topic, and in 15 seconds or so receive suggestions in the form of 15 questions. The process could be iterated ad infinitum, each time with AI returning its set of 15 questions, many new, some repeats. A further benefit was that the user could simply press a button to iterate to the next effort to create 15 questions, or if desired edit the prompt, called a ‘squib’ by Mind Genomics, the request, and see what emerged with the modified input [9]. Figure 1 shows the process. Panel A shows the request for four questions, the step which intimidated. Panel B shows the screen shot with Idea Coach read to receive input from the user. Panel C shows the input provided to Idea Coach by the user. Finally, Panel D shows the first part of the output provided by Idea Coach. Scrolling down revealed the full set of 15 suggested questions. The user simply needed to select a question and the question was automatically added to Panel A. the user could edit the question as well The process was rapid, simple, low cost, creating in its wake a simple system to run these Mind Genomics studies. As a benefit, the program kept a record of these iterations, and when the study set up was complete, the program sent the user the results of iterations, along with AI summarization of the results of the iterations. The process thus became a combination of problem solving and education, one available to every researcher.

Figure 1 shows the set-up process powered by AI embedded in Idea Coach. Panel A shows the request for four questions. Panel B shows the Idea Coach screen, with the box ready for input. The input could be far bigger than shown by the box. Panel C shows the same Idea Coach screen, this time with the box filled with input. Panel D shows the part of the output. The bottom of Panel D shows the steps that the suer can take. The top bar shows the, the opportunity to select a question ad drop it into the set of questions (as well as edit in on the fly). The middle bar show the opportunity to repeat the action without making any changes, which returned the new suggestions in 15-30 seconds. The bottom bar brings the user back to the Idea Coach input, allowing the user to edit the idea Coach input ‘on the fly,’ and then instantly rerun the request.

Figure 1: The Mind Genomics set-up screens under control of the user, with the help of Idea Coach, powered by AI.

Putting AI in Idea Coach to the Test: Providing Situations and Requesting Considered ‘Thinking’

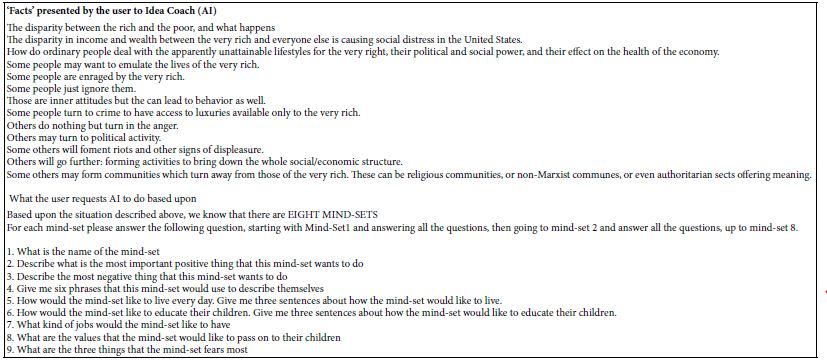

The remainder of this paper focuses on the expansion of AI in the Mind Genomics process, not so much to provide questions and answers for study with people as with the desire to see whether Idea Coach could act more completely, almost as a person. The notion of working with AI to study scenarios is one of the attractions of AI. The objective of Mind Genomics was and remains to weave a coherent story about how people think by presenting them with combination of ideas, and measure how strong each of the ideas was to the person participating in the Mind Genomics study. The fortuitous event leading to this paper and to its companion effort was the it was possible to move Idea Coach into a higher level of functioning, simply by presenting the Idea Coach with a structured request. For this study, the nature of the information leading to request is shown in the top half of Table 1, the section titled: What is posited to be the case today (either by specific statements, or by general attitudes). The set of statements were developed by Arthur Kover, the senior author, as part of his analysis of the current situation in the United States. The actual request itself made to Idea Coach appears in the lower half of Table 2, the section entitled What AI is instructed to do based upon assumption of eight mind-sets. The important thing to keep in mind is the extensive set-up information at the start, and the far more structured request to AI as the follow on.

Table 1: Input to Idea Coach. Top panel = statement of current conditions, presented by user to AI as ‘facts. Bottom panel = request to AI from user.

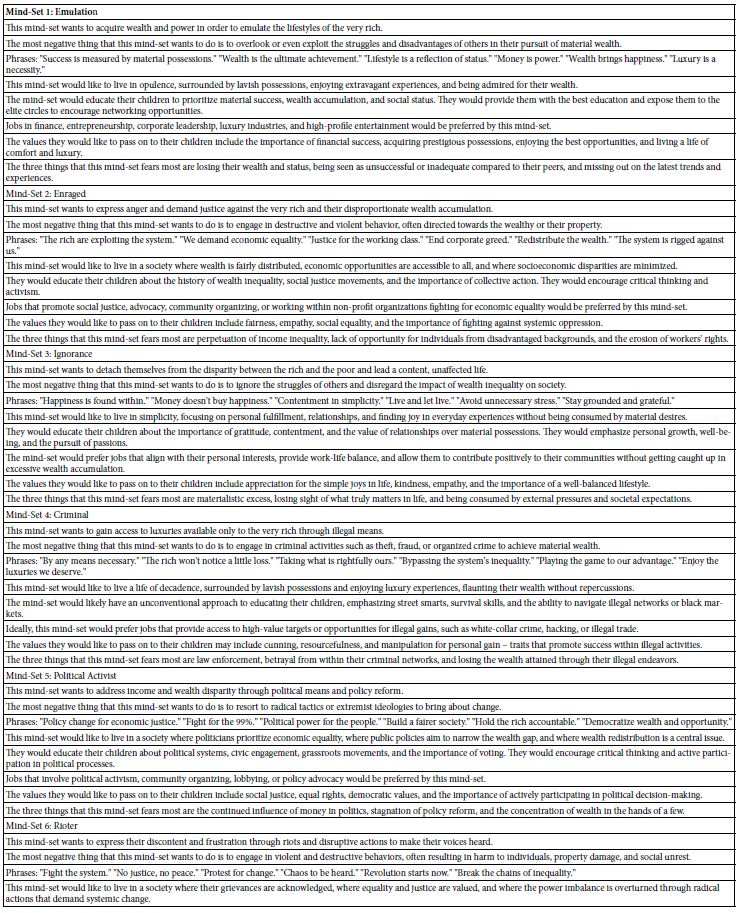

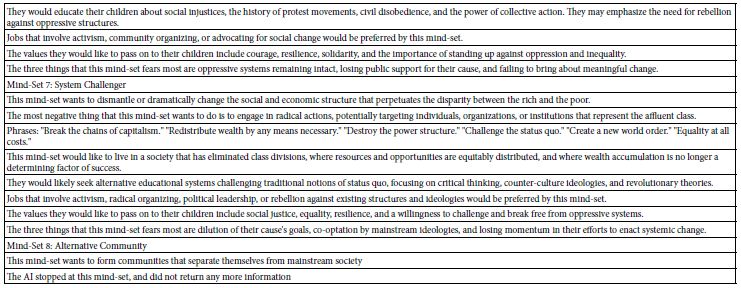

Table 2: The eight mind-sets generated by AI in Idea Coach, based upon the information fed to it by the user (see Table 1, Top panel).

Positing the Mind-sets and Discussing the Way They Think

The first outcome from the AI embedded in the Idea Coach is the list of the mind-sets. Table 2 shows the list, along with the answers to the eight questions. AI provided full answers for seven of the eight ‘suggested mind-sets.’ AI did not provide anything about the eighth mind-set, other than the name ‘alternative community.’ The important things to understand from Table 2 is the depth of information and presumed insight proffered by the AI, when put on a specific question. To be sure, the orientation in Table 1 suggested the number eight for these mind-sets in the instructions to AI. Yet, one cannot fail to be impressed that the AI ‘fleshed out’ these simple statements, providing a context that would be accepted by a researcher, a news reporter, and even a novelist. The information provided by AI, or perhaps ‘spun up’ by AI seems realistic, internally consistent, and quite similar to what a person would say. The implications of this first part of the foray into the topic of today’s issue, the disparity between rich and poor, is the potential of creating a similar set of mind-sets for the dozens or even hundreds of topics facing society, first doing the work as a general topic, and then perhaps adding additional specifications, such as region of the world, period of history, and so forth. Those advances have to wait a little longer, although the speed of AI to answer these questions make it possible to create this large database of expected mind in a reasonably short period of time. Beyond the eight names of mind-sets is the ability of AI to provide answers which seem reasonable at first glance. Sometimes the AI failed to do exactly what the request to Idea Coach specified, such as giving the precise number of sentences or ideas requested, but for the most part the AI delivered what the user requested. Once again, the language and meaning of what was delivered makes intuitive sense, although successive iterations produced different words for the same questions. The variation from iteration to iteration suggests that the AI was using different sets of materials each time, although most likely materials from the same general set. Were there to be enough time and interest, one could run the same request 10 or more time, to see just how much variation in language and tonality would emerge across the 10 iterations. That is a potential topic for future work, to get a sense of the range of material and meanings delivered by AI across different efforts albeit for identical question.

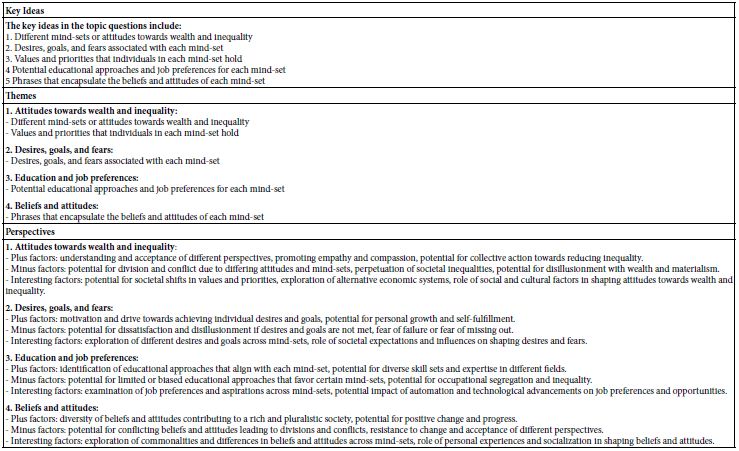

After the user has completed the study set-up the Mind Genomics platform, www.bimileap, returns with summarizations of the idea which had emerged from the initial efforts, viz., questions and answers appearing in Table 1 (background materials), and Table 2 (questions and answers emerging from AI). In a sense Table 3 and successive ‘summarization’ tables provide new knowledge developed by AI.

Table 3 shows three different summaries:

- Key ideas from the material provided

- Themes emerging from the materials generated by AI

- Perspectives on the themes (viz., commentary or new knowledge emerging from further analysis of the themes)

It becomes increasingly clear from this table that the incorporation of AI analyses into the project moves the statement of current conditions (Top panel of Table 1) into a far more profound ‘exegesis’ of the topic. Once again, Table 3 provides the input to help critical thinking about the topic.

Table 3: Summarization of key ideas, themes, and perspectives regarding the themes

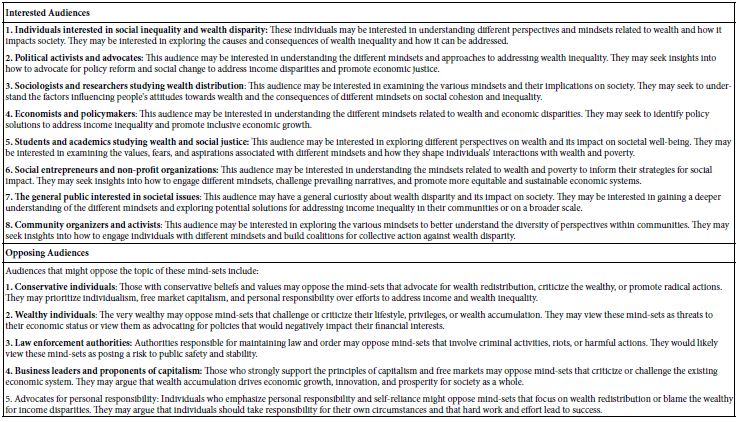

The next step is technically not a summarization of the material, but rather the question of who would be positive about this material (Interested Audiences) versus who would be negative about this material (Opposing Audiences). Table 4 shows these two audiences.

Table 4: Relevant aspects of the issue for Interested Audiences versus for Opposing Audiences

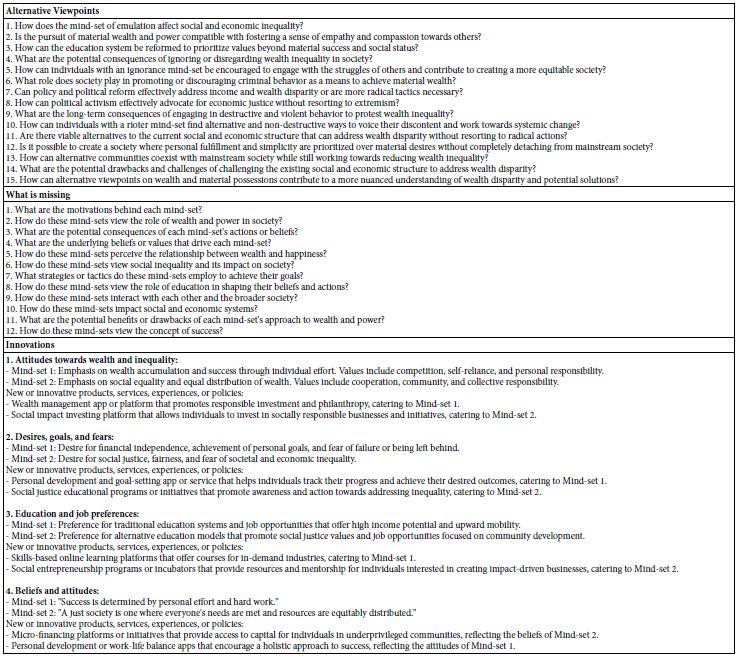

A key benefit of the AI embedded in Idea Coach comes from the ability to identify new aspects, hitherto either unknown or perhaps not particularly well identified. Table 5 shows the final set of summaries. The first summary shows Alternative Viewpoints, which comprise a set of 15 questions presenting new ways of thinking about the topic. The second summary shows What’s Missing, comprising 12 direct questions. The third summary shows suggestions for innovations. This third summary on innovation looks at the topics, recasts the issue in terms new mind-sets for each new idea, and then presents the innovation, and how it will affect each of the newly minted mind-sets. Once again the summarization is new knowledge or at least conjecture, created by AI.

Table 5: New perspectives and suggestions emerging from AI

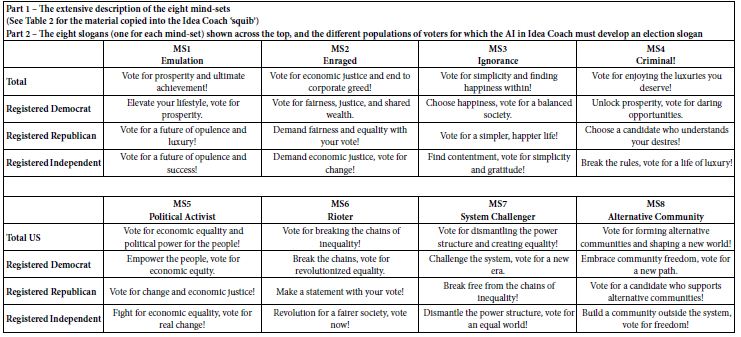

Creating Relevant Slogans for the Presidential Election Using the Mind-sets Generated by AI in Idea Coach

The final product of this experiment appears in Table 6. The product, in the second panel, comprises one slogan for each of the eight mind-sets. Each column corresponds to one mind-set. Each row corresponds to a hypothetical period of time (e.g., 2024, 1892, 1860) to a hypothesized person (e.g., Total US citizen, registered Democrat, registered Republican, registered Independent), and to a statement of economic condition.

Table 6: Slogans developed by AI, based upon instructions to Idea Coach

Discussion and Conclusions

The original thrust of this paper was to explore whether or not artificial intelligence could be used in the world of social policy [10,11], especially to enhance creativity in an area where opinions and power dominate [12]. The topic of AI and social policy has become exceptionally complex, often with the explorations shown in this paper overshadowed by the ethical issues [13,14]. The sheer fact of incorporating machines into society in a way which has the flavor of ‘control’ brings up the shades of George Orwell’s 1984 [15], and predecessor writings of this ilk [16]. The discussions of AI and ‘social research’ focuses primarily on ethics rather than on advances [17,18]. The range and depth of the discussions on AI do not so much focus on specifics but rather on discomfort, fears, which end up showing themselves as seemingly never-end discussions of ethical implications at the level of generality, rather than of specific issues. It may well be that the real contribution of AI to society and to governance have yet to be made, in contrast to the contribution of AI to applications, such as medicine [19], library work in the law [20], etc. It also may be the case that there is justification for the application of AI in situations of power of people over people, with AI giving an advantage in the ‘battle of all against all,’ the perfect description of the Hobbesian nightmare. Such nightmares would not be the case for the benign and often useful application of AI to solve humanity’s problems, rather than the fear of AI which, instead, could create these problems [21,22]. The paper just presented is one in a series of papers exploring the potential of artificial intelligence to promote critical thinking. The issue of critical thinking in the academic world is well covered in numerous publications [23]. There are methods for teaching critical thinking at a young age. The emphasis on critical thinking is to get the student to delve more deeply into a topic, develop hypotheses, test these hypotheses by one or another fashion [24,25]. One of the continuing issues in today’s world is how to make students focus on topics, especially in a world where their attention wanders from the topic or teacher to the little screen, their phone or tablet, where they can be entertained. Is it possible to teach critical thinking within that environment? The study or simulation study reported here may be one way to teach critical thinking about a topic. The issue here is positing and understanding mind-sets, and then creating slogans. The topic is serious, but at another level it is fun, not particularly challenging, returns with interesting results, and most important, returns with results which are real, and which themselves make a major contribution. It would be premature as well as difficult to enumerate the applications of the approach presented here. Within just a few minutes one could take a topic, provide one’s information of any type, instruct the AI to assumed mind-sets without saying what these mind-sets are, and then instruct the mind-sets to answer specific questions. At the surface level the answers make intuitive sense, perhaps because they are not presents facts but trends. It may be at this level, trends, generalities which make intuitive sense, that the approach presented here may enjoy its earliest success. Be that as it may, there may also be a way of presenting the AI with the right question so that the process takes place sometime in the well-defined past, or even sometime in the future. In those cases, one would assume that the AI uses the available information to extrapolate to the new condition. That extension remains for future work, but the effort, cost, speed, and simplicity all argue for an interest ‘next step’ along those lines. The ingoing vision of this study was to understand AI and politics, especially elections. The exiting vision is of a tool in the hands of billions of students, all of whom have fun playing with a system which educates them, makes them prospective experts in a topic with very little difficulty, almost overnight, and for very low cost. To close this paper, it is use to think of the thrust of which this paper is simply the latest. The paper is one of a series of papers exploring the potential of artificial intelligence to promote critical thinking. The issue of critical thinking in the academic world is well covered in numerous publications. The emphasis on critical thinking is to get the student to delve more deeply into a topic, develop hypotheses, test these hypotheses by one or another fashion [26,27]. In the end, it will be critical thinking, hand in hand with the increasing power of AI, which will see the proper use of technology to make a better world, not a world of machines and power-hungry individuals in control.

References

- Moskowitz H, Kover A, Papajorgji P (eds) (2022) Applying Mind Genomics to Social Sciences. IGI Global.

- Harrington B (2016) Capital Without Borders: Wealth Managers and the One Percent. Harvard University Press.

- Moskowitz HR (2012) ‘Mind Genomics’: the experimental, inductive science of the ordinary, and its application to aspects of food and feeding. Physiology & Behavior 107: 606-613.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind genomics. Journal of Sensory Studies 21: 266-307.

- Mazzio J, Davidov S, Moskowitz H (2020) Understanding the algebra of the restaurant patron: A cartography using cognitive economics and Mind Genomics. Nutrition Research and Food Science Journal 3: 1-11.

- Rabino S, Moskowitz H, Katz R, et al. (2007) Creating databases from cross‐national comparisons of food mind‐sets. Journal of Sensory Studies 22: 550-586.

- Siegrist Jr RB (2013) Patient satisfaction: history, myths, and misperceptions. AMA Journal of Ethics 15: 982-987.

- Abdul ah M, Madain A, Jararweh Y (2022) ChatGPT: Fundamentals, applications and social impacts. In 2022 Ninth International Conference on Social Networks Analysis, Management and Security (SNAMS) IEEE, pp 1-8.

- Moskowitz H, Todri A, Papajorgji P, et al. (2023) Sourcing and vetting ideas for sustainability in the retail supply chain: The contribution of artificial Intelligence coupled with Mind Genomics. International Journal of Food System Dynamics 14: 367-380.

- Cheng L, Varshney KR, Liu H (2021) Socially responsible ai algorithms: Issues, purposes, and challenges. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 71: 1137-1181.

- Schiff D, Biddle J, Borenstein J, Laas K (2020) What’s next for ai ethics, policy, and governance? a global overview. In Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, pp. 153-158.

- Gobet F, Sala G (2019) How artificial intelligence can help us understand human creativity. Frontiers in Psychology, 19 June 2019 Sec. Cognition Volume 10 – 2019. [crossref]

- Oravec JA (2019) Artificial intelligence, automation, and social welfare: Some ethical and historical perspectives on technological overstatement and hyperbole. Ethics and Social Welfare 13: 18-32.

- Ouchchy L, Coin A, Dubljević V (2020) AI in the headlines: the portrayal of the ethical issues of artificial intelligence in the media. AI & SOCIETY 35: 927-936.

- Sudmann A, Waibel A (2019) That is a 1984 Orwellian future at our doorstep, right? Natural Language Processing, Artificial Neural Networks and the Politics of (Democratizing) AI.

- Roazen Paul (1978) The Virginia Quarterly Review 54: 675-695.

- Floridi L, Cowls J, King TC, d Taddeo M (2021) How to design AI for social good: seven essential factors. Ethics, Governance, and Policies in Artificial Intelligence, pp. 125-151.

- Hong JW (2022) With great power comes great responsibility: inquiry into the social roles and the power dynamics in human-AI interactions. Journal of Control and Decision 9: 347-354.

- Subramanian M, Wojtusciszyn A, Favre L, et al. (2020) Precision medicine in the era of artificial intelligence: implications in chronic disease management. Journal of Translational Medicine 18: 1-12.

- Armour J, Sako M (2020) AI-enabled business models in legal services: from traditional law firms to next-generation law companies?. Journal of Professions and Organization 7: 27-46.

- Assibong PA, Wogu IAP, Sholarin MA, et al. (2020) The politics of artificial intelligence behaviour and human rights violation issues in the 2016 US presidential elections: An appraisal. In Data Management, Analytics and Innovation: Proceedings of ICDMAI 2019, Volume 2 (Springer Singapor, pp. 295-309).

- König PD, Wenzelburger G (2020) Opportunity for renewal or disruptive force? How artificial intelligence alters democratic politics. Government Information Quarterly 37:101489.

- Kreps S, McCain RM, Brundage M (2022) All the news that’s fit to fabricate: AI-generated text as a tool of media misinformation. Journal of Experimental Political Science 9: 104-117.

- McPeck JE (2016) Critical Thinking and Education. Routledge.

- Jenkins EK (1998) The significant role of critical thinking in predicting auditing students’ performance. Journal of Education for Business 73: 274-279.

- McLaren BM, Scheuer O, Mikšátko J (2010) Supporting collaborative learning and e-discussions using artificial intelligence techniques. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education 20: 1-46.

- Westermann C, Gupta T (2023) Turning queries into questions: For a plurality of perspectives in the age of AI and other frameworks with limited (mind) sets. Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research 21: 3-13.