Abstract

Introduction: Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) involves partial or total removal of external female genitalia. The practice has no health benefits for girls and women. Somaliland is among the countries with the highest prevalence of FGM-C in the world.

Objective: To measure the magnitude and describe the trends of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting among women attending Antenatal Care (ANC) and Delivery service at Edna Adan University Hospital, Hargeisa, Somaliland.

Methods: Edna Adan University Hospital, Hargeisa, Somaliland continuously records FGM/C status of pregnant mothers coming for ANC and delivery services since 2002. 13,320 antenatal and delivery cases were reviewed using a pre-determined checklist. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 20, descriptive statistical analysis was performed. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results: Among the 13,320 reviewed charts, the overall prevalence of FGM/C was 96%. The reason for the majority (31.8%) of the FGM/C cases was traditional beliefs. Moreover, the majority (60.1%) of the FGM/C was performed by the traditional birth attendants (TBA). The median age that FGM/C is performed is 8 (IQR=3). The majority of girls are aged 7-10 when the procedure is performed. From 2002-2007, it was more common for an old woman to perform FGM; from 2007-2018, a traditional birth attendant conducted the procedure. Type III FGM/C (infibulation) appears to be the most commonly practiced type of FGM/C across the board.

Conclusion: The magnitude of FGM/C is high in Somaliland and is still practiced especially among women who are illiterate. The procedure is performed by traditional birth attendants for traditional reasons. Instigating interventions that would provide risk and benefit based health education to communities and promote girl-child education beyond the primary level could help end the practice.

Keywords

Edna Adan University Hospital, Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting, Somaliland, Traditional Birth Attendant

Introduction

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia and/or injury to the female genital organs, whether for cultural or any other non-therapeutic reasons [1]. Globally, an estimated 200 million girls and women have undergone the cut, and approximately 70 million girls aged 0-14 years are at risk of being cut [2]. In a 2016 study, 25 communities living in the MaroodiJeex and Togdheer regions of Somaliland reported that the overall prevalence of FGM/C was 99%, with 80% having undergone infibulation [3].

The nomenclature for the practice varies across countries, ideological perspectives and research frames. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), female genital mutilation is classified into four major types:

Type 1: Excision of the prepuce with or without excision of the clitoris (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Type I of WHO classification of female genital mutilation/cutting

Type 2: Excision of the clitoris with partial or total excision of the labia minora (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Type II of WHO classification of female genital mutilation/cutting

Type 3: Excision of part or all of the external genitalia and stitching together of the exposed walls of the labia majora, leaving only a small hole (typically less than 5cm) to permit the passage of urine and vaginal secretions. This hole may need extending at the time of the menarche and often before first intercourse (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Type III of WHO classification of female genital mutilation/cutting

Type 4: This includes all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes (e.g. pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterizing the genital area) [4].

Though FGM is practiced in more than 28 countries in Africa and a few scattered communities worldwide, its burden appears to be felt most heavily seen in Nigeria, Egypt, Mali, Eritrea, Sudan, Central African Republic (C.A.R.), and the northern part of Ghana where it has been an old traditional and cultural practice of various ethnic groups. The highest prevalence rates are found in Somalia, Somaliland, Djibouti and the Somali Region of Ethiopia where FGM is virtually universal [5].

Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) inflicts life-long injuries on women and their female children. It constitutes a violation of women’s fundamental human rights and threatens their bodily integrity. Historically performed by elderly women, or traditional birth attendants, FGM/C is a physically invasive procedure often associated with multiple adverse impacts [6]. FGM/C in Somalia and Somaliland is frequently performed on girls aged 5-9. This represents a shift in practice. Traditionally, FGM/C was performed in adolescence as an initiation into womanhood, but that is not true in Somali practices since FGM is performed in early ages [7]. Moreover, girls are one-third less likely to be cut than 30 years ago. According to the UNFPA-UNICEF joint program report on FGM/C,22 of the 30 of the countries involved where FGM is practiced and who are considered “least-developed” [8]. The health impacts associated with FGM/C that require interventions have been broadly categorized into the following categories: immediate, genito-urinary, gynecological, obstetric, sexual, and psycho-social consequences [9].

The reason why FGM is performed varies from one region to another as well as over time, and includes a mix of sociocultural factors within families and communities. In places where FGM is a social convention, strong motivations to perpetuate the practice of FGM include: the pressure to conform to what others have traditionally been doing, the need to be accepted socially, and the fear of being rejected by the community. Furthermore, FGM is often considered a necessary part of raising a girl, and a perceived requirement to prepare her for adulthood and marriage. In addition, FGM is often motivated by beliefs about what is considered acceptable sexual behavior. It aims to ensure premarital virginity and marital fidelity, by proving that her vulva has not been opened previously by any other man. Moreover, FGM is associated with cultural ideals of femininity and modesty, which include the notion that girls are clean and beautiful after removal of body parts that are considered unclean, unfeminine, or male [10].

In Somaliland, despite the continuous pledge to end female genital mutilation/cutting, this centuries-old practice still continues for non-medical reasons. Furthermore, the problem is not well-documented and reported. The majority of the studies about the prevalence and trends of FGM/C are based on reports from women attending health institutions. Moreover, community-based studies are expensive in nature. Information acquired from the woman’s own account has limitations since the woman might not easily understand the anatomy of her female genitalia nor be able to accurately classify the type of FGM/C that was performed on her. In order to overcome the limitations of such studies, reviewing hospital records and describing the magnitude and pattern of FGM/C must be appropriately verified by midwives and physicians. Moreover, understanding these phenomena could guide efforts to curb this harmful practice and reduce the morbidity and mortality of mothers and children. Furthermore, the investigators have developed the following research questions:

What is the overall prevalence of FGM/C in Somaliland?

What is the most prevalent type of FGM/C in Somaliland?

What does the trend of FGM/C look like since 2002?

What is the average age of practicing the FGM/C?

Is there association between FGM/C and educational status of the mother?

Method and Materials

Description of the Study Area and Study Setting

General Setting

According to the Somaliland Health and Demographic Survey 2020 (SLHDS, 2020) report, over 48 percent of Somaliland’s population is under the age of 15 years old, and 48 percent of the population is within the working age group (15-64 years old). The population of Somaliland has an average household size of six. Early marriage is common, particularly for women, as 23 percent aged 20 -24 interviewed were married by the time they turned 18 years old. FGM/Chas been practiced in Somaliland for several decades with insignificant declination. Furthermore, more than 70 percent of women indicated that the forms of domestic violence they are subject to by their husbands are physical assault, denial of education, forced marriage, rape, and sexual harassment. SLHDS noted that an overwhelming 67 percent of births were delivered at home. The death rate among reproductive age women is highest with 9.4 deaths per 1,000 populations, among women aged 30-34. This is also the age group in which childbearing hits its peak. Somaliland’s Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR) is 396 per 100,000 live births. Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) is prevalent among 98% of women in their reproductive age [11].

Study Site

Edna Adan Ismail, a UK/US trained Somaliland certified nurse midwife, has been seeing patients with cases of FGM/C for the duration of her 50 years of midwifery experience, and has been engaged in a life-long struggle to put an end to this practice. With the establishment of her maternity hospital which is now a major teaching and referral general hospital, as well as with the still much-needed national services to combat FGM/C practices, it has become essential for the hospital to lead a campaign to tackle this tradition against women’s rights. The hospital is fast becoming a repository of all information relating to FGM/C in Somaliland and the region. The hospital has been registering mothers coming to the hospital for antenatal care (ANC) and delivery service since 2002. Though these were used as audit reports, these huge data sets have not been adequately analyzed. This research team has been established to conduct a detailed analysis and point out the important findings that would answer the above listed research questions and contribute for planning and interventions to end FGM/C by all stakeholders.

Study Design and Population

We conducted a 17 years’ retrospective hospital-based medical-record review in February 2022. After securing ethical clearance from the Edna Adan University Hospital Ethical Review Committee (ERC), we reviewed all 13,320 records of women who visited the antenatal clinic and who gave birth at Edna Adan University Hospital between the years 2002-2018. The female genital mutilation or cutting (FGM/C) data has been continuously recorded by the hospital starting from 2002 to 2018.

Data Extraction and Analysis

The data was extracted from the ANC and delivery charts using a predetermined English version data extraction checklist by 18 senior public health students and another two supervisors who were trained for three days on how to extract information from the ANC and delivery charts. Extracted data was cross-checked by the research assistants and all necessary modifications were made. Moreover, data entry, editing, coding and recoding, descriptive statistics, numerical summary measures, and analytic statistical tests such as Chi-square test and correlation tests were done using SPSS version 20 statistical software by the principal investigator and the research team. p-value and 95% confidence interval was used to determine if there was association among the variables or not. p-value less than 0.05 was considered a statistically significant association. In this study, classification of FGM/C was in accordance to the World Health Organization (WHO). After extraction of the required information, the charts were kept confidential and sent back to the hospital repository.

Variables

The following variables were extracted from the records: sociodemographic characteristics such as age, residence, educational status, and the year the data was collected; and FGM/C related variables such as FGM/C status, FGM/C type, reason for FGM/C, agent who performed the practice and place it was performed, age FGM/C was performed, as well as if FGM/C of daughter was performed and the reason for FGM/C.

Ethical Approval

Ethical clearance was solicited from the office of research and ethical committee of the Edna Adan University Hospital (ERC: EAUH/5973/22, dated 23 February, 2022) and confirmation of permission to access the data from the archives was secured from the hospital Director. The patient charts were properly handled ensuring the respect for the confidential nature of the survey during the data extraction and returning the charts to the repository of the hospital for storage.

Results

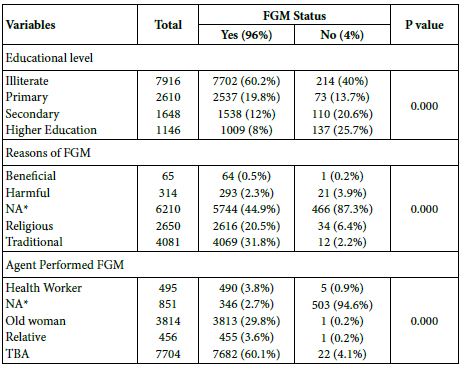

We reviewed and explored total of 13,320 ANC charts about the educational level of the clients, the reasons for performing FGM/C and the agent responsible for performing the procedure – we found that the overall prevalence of FGM/C in the patient population was 96%. The majority (60.2%) of the FGM/C were illiterate. And, the reason for the majority (31.8%) of the FGM/C cases was for traditional belief. Moreover, the majority (60.1%) of the FGM/C was performed by the traditional birth attendants (Table 1).

Table 1: Distribution of educational level, reasons for FGM/C and agent who performed the procedure, Hargeisa, Somaliland

NA* refers to Not Available

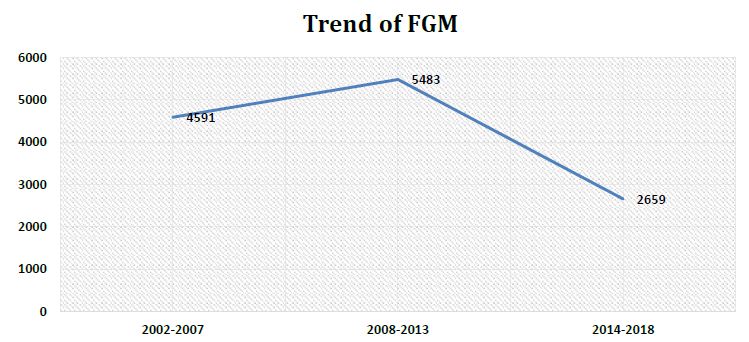

We have also run an analysis to look at the trend of the FGM/C and it depicts that there is a slight increase from 2002-2007 to 2008-2013, whereby the number of FGM/C procedures performed goes from 4591 (36%) to 5483 (43%). However, there is a steady decline of cases from 2008-2013 to 2014-2018 in which the cases reported was 2659 (21%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: A 17 years’ trends of Female Genital Mutilation in Hargeisa, Somaliland

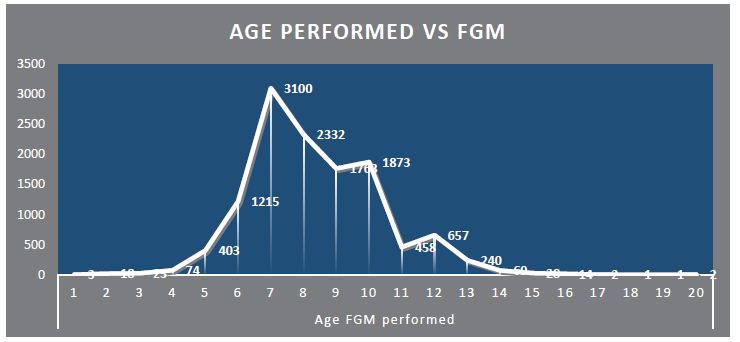

The following figure shows that the median age that FGM is performed is 8 (IQR= 3) years old. The majority of girls are aged 6-10 when FGM is performed. Moreover, FGM/C declines sharply after the age of 12 and almost insignificant before the age of 4 (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Distribution of the age FGM/C is Performed, Hargeisa, Somaliland

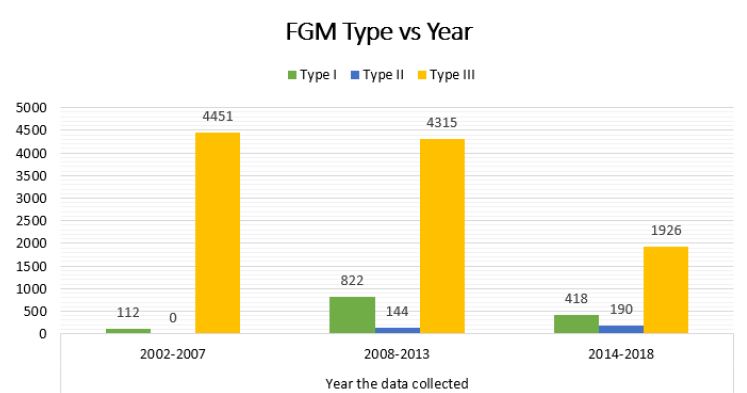

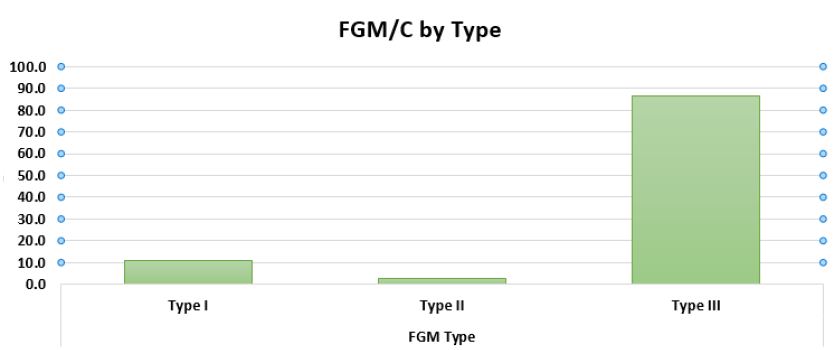

Even though there are fluctuations across the 17 years, it is observed that from 2002-2007 had the highest record rates of type III FGM/C 4451 (36%), as well as in 2008-2013 were the number of cases was 4315 (35%) though number of cases were declining 2014-2018, 1926 (16%). Type III FGM/C (infibulation) appears to be the most commonly practiced type of FGM/C across the board (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Distribution of FGM type per year, Hargeisa, Somaliland

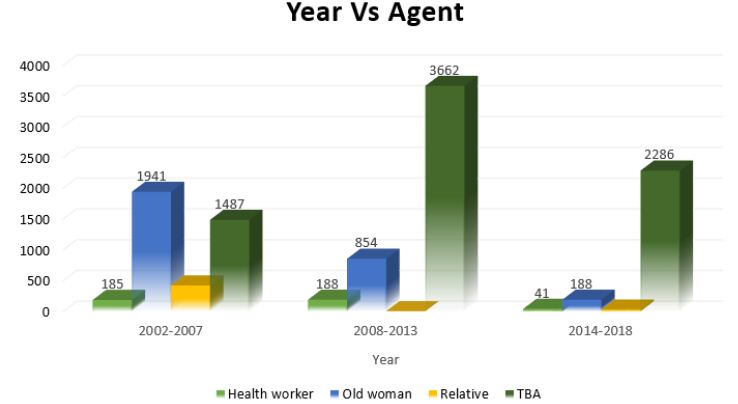

The following figure denotes that from 2002-2018, an old woman or traditional birth attendant were most commonly those that performed FGM/C. From 2002-2007, it was more common for an old woman to perform FGM, whereas from 2007-2018, a traditional birth attendant did the procedure (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Distribution of the year and the agent who performed the FGM/C. Hargeisa, Somaliland

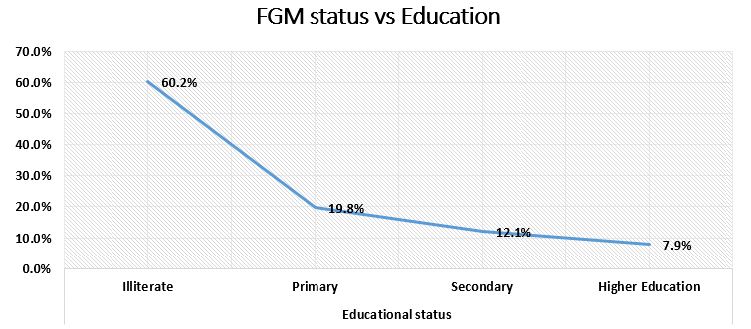

We used Chi-squared test statistic to assess whether education level and FGM/C status are associated, and we found that there is a statistically significant association (p-value=0.001). Moreover, we observed a sharp decrease in likelihood to perform the FGM/C procedure as education level rises. In addition, those that perform FGM/C on their daughters are most commonly illiterate (Figure 8).

Figure 8: The pattern of FGM/C cases versus Educational Level, Hargeisa, Somaliland

Type III FGM is found in almost 87 percent of the population we studied from 2002-2018, making it the most common type of FGM performed among those studied (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Distribution of the Type of FGM/C, Hargeisa, Somaliland

Discussion

Somaliland continues to house a high prevalence of the phenomena known as female genital mutilation and cutting, compared to other countries in the horn of Africa and in Eastern Africa. This could be attributed to the fact that Edna Adan University Hospital is the only hospital in Eastern Africa that we know of that collects such data. As previously stated, the problem is not well-documented and reported; due to this, our research team set out to encapsulate the data of 13,320 women polled at the Edna Adan University Hospital in Hargeisa, Somaliland to fully grasp the magnitude and trends of FGM/C, based upon women’s reports taken during their antenatal appointments at our health institution. Their information was kept confidential throughout the entirety of the process and the patient files were returned to the repository in which they were stored upon completion of the analysis of the data presented.

The investigators developed the following research questions in order to fully understand the data gathered from 2002-2018: What is the overall prevalence of FGM/C in Somaliland? What is the most prevalent type of FGM/C in Somaliland? What has the trend of FGM/C looked like since 2002? What is the average age of those who had undergone FGM/C? Is there an association between FGM/C and educational status?

The current study reveals that the overall prevalence of FGM/C is 96% among the patients who attend Edna Adan University Hospital that may not give a true picture of the situation in Somaliland. However, this result goes beyond previous studies conducted in Tanzania, Nigeria, Yemen, Burkina Faso, Gambia, and Mauritania, where the prevalence of FGM/C was (45.2%, 45.9%, 48%, 68.1%, 75.6%, and 77%), respectively [12-17].

Moreover, the major findings associated with the research questions presented are as follows: it appears that there is a slight increase in the trend of FGM from 2002-2007 to 2008-2013, where the number of FGM/C procedures performed goes from 4591 (36%) documented cases to 5483 (43%) documented cases. There was a steady decline in cases from 2014-2018 which the case reported was 2659 (21%). Besides, our study is against when compared to a meta-analysis conducted in Ethiopia where the prevalence of FGM/C was higher from 2013-2017 (78.39%, 95% CI: 48.2, 108.5) [18].

A similar study conducted in Egypt to assess the prevalence of FGM among girls showed that the average age at which girls underwent FGM was 10.1 years, which is higher when compare to our findings that it is 8 years old [19]. Moreover, in our study, the majority of girls are aged 6-10 when FGM is performed.

Furthermore, it appears that in 2002-2007, record rates of type IIIFGM occurred, as well as in 2008-2013. Type III FGM seems to be the most common type of FGM performed across the span of the data in its entirety. Between 2002 and 2018, type III FGM was observed in 87 percent of the population studied. As a result, it is the most common type of FGM among those studied. This result ties well with a previous study conducted in Sudan, wherein type III FGM was the most common practice, while 66 percent of those who had undergone FGM had type III FGM [20].

Nevertheless, when it comes to agents who performed FGM, a study carried out in Burkina Faso explored that traditional practitioners performed the vast majority (82.4%) of FGM [15]. However, it is also a point of interest to note that the data suggests that an old woman or traditional birth attendant were most commonly those who performed FGM. From 2002-2007, it was more common for an old woman to perform FGM, whereas from 2008-2018, a traditional birth attendant performed the procedure.

Another study conducted in the United Arab Emirates to assess the association between educational status and FGM/C found that there is a statistically significant association between FGM status and educational level (p-value 0.001). Moreover, there was an inverse association between FGM status and literacy level: with increasing educational levels, there was a decrease in the proportion of women with FGM/C [21]. This result ties well with our data, which indicates that there is a sharp decrease in the likelihood of performing the FGM procedure as education level rises. Those that perform FGM on their daughters are most commonly illiterate. As the family’s education level rises, they are less likely to perform FGM on their daughter, suggesting there is a strong association between the education level of the family (the mother specifically) and the likelihood that she will organize the FGM/C procedure to be committed for her daughter (s) (p-value 0.001). We consider this to be the most important finding because if wide-spread education about the harms and tribulations of FGM/C and its long-term and short-term effects on those it is performed upon could target far-reaching communities as well as those in big cities, there may be a notable shift in the number of FGM/C cases seen in Hargeisa, Somaliland and other surrounding areas.

Alternatively, it is possible that the decrease in FGM/C cases is not solely attributable to the rise in education levels of the family. It could be possible that campaigns against the practice of FGM/C are also influencing attitudes towards FGM/C which are shifting ever so slightly with the younger population as they enter their reproductive years. Further studies to explore this variable would have to be conducted in order to be confirmed.

In regards to the type of FGM/C that is most commonly performed, it is possible that the data is not entirely accurate and can only be confirmed if a healthcare provider (nurse, midwife, or doctor) does a thorough exam of the patient’s genitals in order to confirm if it is indeed type I, II, or III FGM/C that was performed. It is highly likely that the women do not fully grasp the difference between the types of FGM or can accurately report the type that was done to them. During ANC, it is the nurse or midwife who physically examines the patient and who verifies the type of FGM/C seen in the patient.

There were limits to the study as well – the data for 2005, 2006 and 2019 appears to be incomplete and, due to very scarce data in 2019, it was omitted from the report. The data for 2020-2022 has not been documented during antenatal appointments, so our data is only up to date insofar as 2019.

Another limit is the amount of data made available to the research team-in order to fully encapsulate the prevalence of FGM/C in this area of Africa, other hospitals in Somaliland, as well as in neighboring countries, would have to be included in the study as a means of comparison. That extent of data was not made available to this research team, and further research would need to be done in order to accurately capture the desired results.

Conclusion

In this study, we documented and reported women’s sociodemographic characteristics such as age, residence, educational status, and the year the data was collected; and FGM/C related variables such as FGM/C status, FGM/C type, reason for FGM/C, agent who performed the practice and place it was performed, age at which FGM/C was performed, as well as if FGM/C of a daughter was performed and the reason for FGM/C. We chose these variables in the hope that trends in the data would appear. Most notably, there is an association between the education level of the mother and the likelihood that she will perform FGM/C on her daughter. There also appears to be a great likelihood that type III FGM/C will be performed on girls, the median age that FGM is performed is 8 years old, most commonly between the ages of 6 and 10, and that the procedure will be done either by a traditional birth attendant or an old woman in the community.

Overall, it appears that FGM/C is not decreasing in prevalence as the years go by. Further research into the prevalence for the years 2019-2022 should be conducted in order to accurately capture the number of FGM/C cases seen at Edna Adan University Hospital until now. Further data should have to be collected from the surrounding hospitals in order to conduct a comparative analysis.

Acknowledgement

We are pleased and thankful to Edna Adan University Hospital. We also acknowledge our data collectors for their tireless effort.

References

- Organization WH (1998) Female genital mutilation: an overview: World Health Organization.

- Shell-Duncan B, Naik R, Feldman-Jacobs C (2016) A state-of-the-art synthesis on female genital mutilation/cutting: What do we know now?

- Newell-Jones K (2016) Empowering communities to collectively abandon FGM/C in Somaliland. Action Aid. 2016.

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation [Internet].

- Okeke TC, Anyaehie U, Ezenyeaku C (2012) An overview of female genital mutilation in Nigeria. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research 2: 70-73. [crossref]

- Berg RC, Underland V (2014) Gynecological consequences of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C): Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter for helsetjenesten. [crossref]

- UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation, August 2018.

- Activities UNFfP (2015) Demographic perspectives on female genital mutilation: UNFPA.

- Berg RC, Underland V, Odgaard-Jensen J, Fretheim A, Vist GE (2014) Effects of female genital cutting on physical health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 4: e006316. [crossref]

- World Health Organization (WHO) fact sheets, Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), 21 January 2022 [Internet].

- The Somaliland Health and Demographic Survey 2020 (SLSDH 2020).

- Klouman E, Manongi R, Klepp KI (2005) Self‐reported and observed female genital cutting in rural Tanzania: Associated demographic factors, HIV and sexually transmitted infections. Tropical Medicine & International Health 10: 105-115. [croosref]

- Snow RC, Slanger TE, Okonofua FE, Oronsaye F, Wacker J (2002) Female genital cutting in southern urban and peri‐urban Nigeria: self‐reported validity, social determinants and secular decline. Tropical Medicine & International Health 7: 91-100. [crossref]

- Alosaimi AN, Essén B, Riitta L, Nwaru BI, Mouniri H (2019) Factors associated with female genital cutting in Yemen and its policy implications. Midwifery 74: 99-106. [crossref]

- Inungu J, Tou Y (2013) Factors associated with female genital mutilation in Burkina Faso. Journal of Public Health and Epidemiology 5: 20-28.

- Kaplan A, Forbes M, Bonhoure I, Utzet M, Martín M, et al. (2013) Female genital mutilation/cutting in The Gambia: long-term health consequences and complications during delivery and for the newborn. International Journal of Women’s Health 5: 323. [crossref]

- Ouldzeidoune N, Keating J, Bertrand J, Rice J (2013) A description of female genital mutilation and force-feeding practices in Mauritania: implications for the protection of child rights and health. PLoS One 8: e60594. [crossref]

- Fite RO, Hanfore LK, Lake EA, Obsa MS (2020) Prevalence of female genital mutilation among women in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 6: e04403. [crossref]

- Tag-Eldin MA, Gadallah MA, Al-Tayeb MN, Abdel-Aty M, Mansour E, et al. (2008) Prevalence of female genital cutting among Egyptian girls. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86: 269-274. [crossref]

- Satti A, Elmusharaf S, Bedri H, Idris T, Hashim MSK, et al. (2006) Prevalence and determinants of the practice of genital mutilation of girls in Khartoum, Sudan. Annals of Tropical Pediatrics 26: 303-310. [crossref]

- Al Awar S, Al-Jefout M, Osman N, Balayah Z, Al Kindi N, et al. (2020) Prevalence, knowledge, attitude and practices of female genital mutilation and cutting (FGM/C) among United Arab Emirates population. BMC Women’s Health 20: 1-12.