Abstract

This is an ethnological analysis of six unique geology reserves (or geoparks) each being the center of a larger geological landscape (or geoscape). Each park has been given special historical preservation status in the United States because of its cultural meanings to Native Americans and its special geological features. Ethnographic studies were funded to understand the special cultural connections between individual geological areas and cultural a more general ethnological perspective on such heritage places. The authors of this analysis participated in the ethnographic study of four of the six affiliated Native Americans. This analysis further compares these findings, drawing out four themes common across the case studies and thus producing geoparks.

Keywords

Landscapes of origin, Geoparks, Geoscapes, Pilgrimage, North American, Native American sacred areas

Background

The most current understanding of the UNESCO preference for using geology heritage terms like geoparks for research and management is discussed in a special issue of the journal Land entitled Geoparks, Geotrails, and Geotourism—Linking Geology, Geoheritage, and Geoeducation that was edited by Margaret Brocx and Vic Semeniuk [1]. They summarize the worldwide movement towards using these concepts to better understand heritage places that involve a number of geoparks and geotrails that have been established, e.g., UNESCO. Global Geoparks where the geology, geotours, and local economy are linked for the well-being of the local people and operate under the auspices of UNESCO, and National or State-oriented geoparks/geotrails where the geology is identified as significant and preserved in conservation estates and utilized for tours, education, and other commercial purposes. Well-designed and organized geoparks/geotrails provide valuable sites for geoeducation, including suitable localities for collecting minerals and fossils, and all types of geoparks/geotrails can function for geotourism. Geotours in geoparks/geotrails provide excellent opportunity for introducing the public and students to the wealth of information and history that the Earth has to offer and professional geologists to the diversity of Earth Science globally. This analysis contributes to our understanding of the UNESCO use of geoparks by demonstrating how Effigy Mounds National Monument (NM) and its surrounding ceremonial landscape fits into a broader discussion of multi-ethnic [Ethnicity is the social organization of cultural difference (Barth 1969). We use ethnic groups here to denote socially defined subdivisions of a common cultural heritage. Ethnic group membership tends to be organized by a number of boundary mechanisms, which may include shared religious practices, ancestry and descent, origin stories, geographies of and attachments to place, and language] ceremonial centers also known here as Landscapes of Origin and geoscapes. The purpose of this ethnological analysis is to show that, while Effigy Mounds has its own unique functions and connections, it parallels other ceremonial centers discussed in this analysis. The six case studies presented here were selected to demonstrate how some time-keeping elements using geological features, healing places, and renewal ceremonial locations are comparable with other heritage geoparks. In a book entitled Landscapes of Origin in the Americas: Creation Narratives Linking Ancient Places and Present Communities, Jessica Christie (2009) [2] assembled nine case studies of how Native American ethnic groups understand, use, and are attached to origin places. The cases are from North, Central, and South America. The organizing thesis of her book is that Creation is a complex concept which variously can mean where we came into previous worlds, where we came into the current world, or where we were culturally recreated as a result of some monumental event.

All Creation events discussed here, and thus their recounting through time, are tied totopographic places and, often, multiple geological features. Normally these places are topographically spectacular—the junctions of large rivers, a salt deposit in the caldera of a massive volcano, a mountain in a flat terrain, or the outcropping of a special mineral for making ceremonial pipes. Landscape of Origin naturally has a destination area, which is the focus of various kinds of ceremonies such as those associated with world balancing and conflict resolution activities, individual vision quests, and spiritual healing. At the center of the destination there often are a series of sequential use protocols which we have termed local ceremonial landscapes [4,5]. The journey to the destination center typically occurs along well established pilgrimage trails, which in turn have functionally special locations for ceremony (Grassy pubs). This ethnological analysis helps us to understand Effigy Mounds by placing it in a wider Native American heritage geoscape frame.

Landscapes of Origin

Tribal representatives describe Effigy Mounds [Effigy Mounds is used in this article instead of the acronym Effigy Mounds NM in order to talk about not only the monument lands but also the surrounding immediate landscape. The distinction upholds Native American uses shared during ethnographic interviews] as a large ceremonial center, which is located in an extensive, functionally integrated cultural landscape, called here a Landscape of Origin. The Effigy Mounds center and landscape have been used by many different Native American groups for thousands of years. Native American people have long maintained connections to Effigy Mounds through ceremonial activity and their origin and creation stories. Effigy Mounds also has been understood as an area free from inter-ethnic conflict; thus all culturally associated tribes have an inherent right to visit for ceremonial activities and conflict is not allowed in this sacred space. With these core understandings, it is important to place Effigy Mounds into a broader discussion of multi-ethnic ceremonial centers (Figure 1).

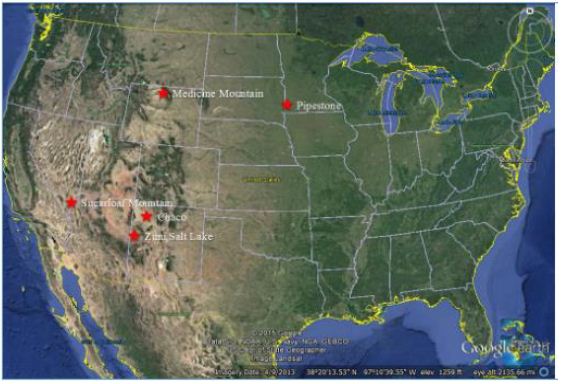

Figure 1: Map Placing the Five Multi-Ethnic Ceremonial Areas

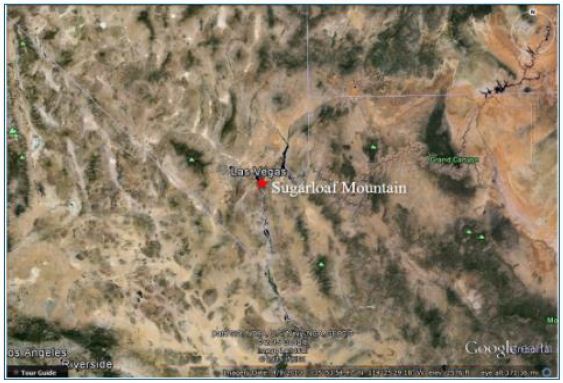

This essay describes and compares six (6) Native American Landscapes of Origin including Effigy Mounts, in North America. The five other cases are (1) Pipestone National Monument (Pipestone), (2) Medicine Wheel/Medicine Mountain National Historic Landmark (Medicine Mountain), (3) the Zuni Salt Lake and Sanctuary (Zuni Salt Lake), (4) Chaco Culture National Historical Park (Chaco), and (5) Sugarloaf /Gold Strike Canyon (Sugarloaf Mountain) (Figure 2.1). The patterns or elements of these well-known Native American geoparks and geoscapes are used to situate Effigy Mounds as a ceremonial center.

Effigy Mounds

In the past, a number of Native American groups visited places located within the monument boundaries and the surrounding landscape for a variety of reasons, such as holding ceremony, burying their dead, and maintaining the mounds (Figure 2). While at this ceremonial center, interactions between the diverse groups were peaceful, due to the shared value of the mounds as a neutral zone for ceremonial use (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Landscape and Viewscape from the Marching Bear Group

Howey, whose work focused on mound groups in northern Michigan, suggests that mound groups may have served as ceremonial areas that build on pan-residential interaction and trade [6]. She argues that embedding these centers in the sacred allows members of communities from separate territories to meet and exchange goods where liturgical order ensures moral behavior, therefore public ritual restrains individual competition or hostility [6]. In short, the political functions of public ritual were just as important as the religious functions. These mounds were centered in shared ritual that brought communities from great distances. These relationships strengthened social bonds between territorially distinct groups and added group interdependencies through economic specialization. Building upon his research on mounds in South America, Dillehay [7] notes that once monuments are engaged in public ritual, they organize people’s responses and patterns of interaction. Similar cultural use patterns occurred along the Upper Mississippi River watershed. Tribal representatives maintained that these mounds served as a gathering place for the celebration of the solstice and other ceremonies, as well as the final resting place for spiritual leaders and other deceased community members from a number of tribes. Through time, Effigy Mounds continued to be a sacred place, or spiritual center, lending credence that it was seen as hallowed ground and a place of nonviolence.

Origin Stories

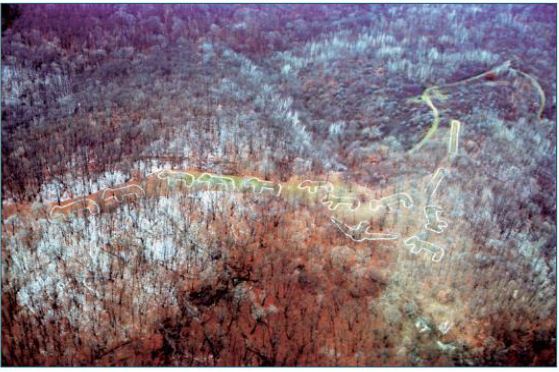

Effigy Mounds are a key component of many Native American tribes’ oral histories and creation stories. According to ethnographic interviews conducted during this study, Dakota, Ioway, and Winnebago have stories that connect them with the various mound groups within the monument. Tribal representatives noted that the zoomorphic effigies are closely linked to medicine and clan origins and migration. In particular, the Marching Bear Group found in the South Unit is associated with a period in history where the Ioway, Winnebago, and others were once part of one larger group of people. At one point the various clans within this larger society agreed to separate peacefully into multiple tribes. An Ioway representative noted that the formation of the Marching Bear Group is representative of that event (Figure 3). Each group broke away and headed their separate ways, one by one.

Figure 3: Aerial View of Marching Bear Group in the South Unit of Effigy Mounds (NPS)

Ho-Chunk oral histories tell of an origin story that tribal representatives believe corresponds to the Marching Bear Group: One night, the Great Spirit appeared to Bear in a dream, “My son,” he said, “it is time to leave your home and go to a new home I have made for you. No longer will you eat solely from the water. There will be other food that I have out there for you to eat.” So Bear called a council with all the other animals, including Wolf, Deer, Eagle, and Buffalo. It was decided that Deer would lead the way, so he and his people left first. Bear and his people left in the second group, followed by Wolf in the third group. Buffalo left the next morning. The final animal to leave was the mighty Eagle. Before he departed, he blessed the people who were left behind. Eagle then flew into the sunrise and disappeared over the mountains. The spirits of the early people watched them leave with tears in their eyes, but happiness in their hearts [8]. Oral history, such as the Ioway and Ho-Chunk stories, reaffirms contemporary Native American people’s connections to Effigy Mounds.

Pilgrimage and Ceremonial Activity

Human societies form complex connections and relationships with the environment that surrounds them. Their cultural understandings of the land are shared and transferred over generations through oral traditions and ceremony [9,10]. Many cultural groups, or ethnic groups, can hold different understandings of the same land [3]. For many Native American people, these engagements are grounded in their epistemologies and oral traditions [11-13]. Places are connected through songs, oral history, human relations, ceremony, and both physical and spiritual trails. These connections create synergistic relationships between people, places, and objects during ceremony. These types of connections and relationships are important for understanding the concept of pilgrimage. The act of pilgrimage involves religious specialists traveling to unique and powerful places and landscapes along special, well-established ceremonial pathways. As the religious specialists, or pilgrims, follow these trails, they perform ritual acts, which are critical to successfully completing the pilgrimage ceremony. The pilgrimage process allowed the pilgrims to gain knowledge and power at their destination places to use in ceremonies to restore balance and promote sustainability in their home communities.

The term pilgrimage is used here to describe the ceremonial journey cultural and religious leaders took when they visited the Effigy Mounds NM area. The UofA team chose this term because it was believed to be the best way to describe how the tribal leaders’ travel and visitation to their area would have hade social and spiritual importance. During pilgrimages, the travelers are left without their normal social structure, and a community or communitas (even if it is temporary) is formed [14]. Pilgrims use these new relationships to develop protocols for how to behave and perform rituals along the trail. These roles are based on the pilgrims’ ceremonial responsibilities and needs that are necessary for a successful pilgrimage. Ceremonial activity brings together people from different communities and cultural backgrounds [15-19].

Effigy Mounds served as a major ceremonial destination place for many Native American groups for thousands of years. Religious specialists followed specific trails, which included both terrestrial and water travel components. During their journeys, religious specialists likely visited places to pray and leave offerings along the routes in order to physically and spiritually prepare themselves to enter Effigy Mounds. Once they reached their destination place, religious specialists engaged in certain types of ceremonial activities. It is believed that certain types of activities occurred seasonally while others occurred annually at Effigy Mounds. According to some of the tribal representatives, ceremonies occurring at various locations within the monument were tied directly to time keeping. At least one mound group found on the high bluffs was constructed and placed in such ways that solar and lunar movements could be observed during the summer solstice. Time keeping is an important activity that exists in all human societies. Designated medicine men/religious specialists were trained for this task by tracking the movements of the planets, stars, moon, and the sun. Originally, physical time was marked at stable places on the landscape. Time often dictates and influences when specific human activities, such as ceremony, take place. Tracking solar and lunar movements plays an especially important role in agriculture; time keeping helps determine the best time for planting and harvesting produce [20]. Another major ceremonial component of Effigy Mounds was the annual activity of reconnecting with the ancestors and memorializing the deceased, as noted by tribal representatives. Annually, Native American people from connected communities visited Effigy Mounds for funeral ceremonies. Families worked together to bring in raw materials to repair and stabilize the mounds. Native American people brought the remains of important community members or religious leaders to be placed in the burial mounds at Sny Magill or on the high bluffs. Additionally, as part of the ritual activities, offerings would be brought and placed in and around the mounds.

Historical Accounts

Reuben Thwaites documented Prairie du Chien, which is located just across the Mississippi River (Figure 4), as a key trading center amongst numerous Native American tribes. [21] asserts that up to 6,000 Native Americans would visit annually. Blaine [22] makes a similar assessment about the region, referring to Prairie du Chien as an “older Indian trading rendezvous.” The proximity to the Wisconsin and Yellow River further affirms the magnitude of trade in this area, tying this landscape to the west via the Yellow River, and to the Great Lakes region via the Wisconsin River. Materials found within the burial mounds in and around Effigy Mounds also help frame the context of centralized trade in this area. Located within the mounds were traces of copper, mica, shells, and obsidian. It is speculated that each one of these materials was traded from areas to the north, south, east, and west.

Figure 4: View of Prairie du Chien from Effigy Mounds

Native American people came together in the Prairie du Chien area for other types of events aside from trade rendezvouses. Early Euro-Americans in the region noted accounts of Native American people coming together to take part in ceremonial games, such as lacrosse. According to the Ho-Chunk Nation’s timeline of their tribal history, over 300 people representing the Winnebago, the Fox, and the Sioux gathered to participate in a large lacrosse tournament near Prairie du Chien [23].

Landscapes of Origin Cases Elsewhere

Various ceremonial centers found in North America were utilized by multiple ethnic groups for a wide range of purposes. These locations had ritualistic and ceremonial components related to Native American epistemology and reinforced both intra- and inter- tribal bonds. Among these locations are: (1) Pipestone, (2) Medicine Mountain, (3) Zuni Salt Lake, (4) Chaco, and (5) Sugarloaf Mountain. The following section provides information on these locations and shows the parallels between them and Effigy Mounds.

Pipestone National Monument Case One

Pipestone National Monument (Pipestone) is located in Pipestone County, near the three-state border of Minnesota, South Dakota, and Iowa (Figure 5). Before the arrival of Europeans, various Native American groups lived in the vicinity of the present-day monument. They, along with other Native American groups who did not live in the immediate vicinity of the monument, visited the quarry in order to obtain catlinite to manufacture ceremonial pipe bowls and other objects. The stone gets its name from nineteenth-century artist, George Catlin, who described and painted it. The monument takes its name from this resource, and later the quarry and adjacent area became a national monument in 1937 [24].

Figure 5: Pipestone Landscape

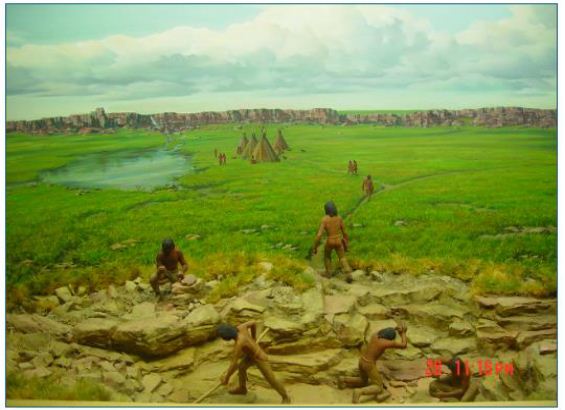

Before Euro-American settlers introduced drastic changes to its natural landscape, the monument included some wetlands and tall grass prairies. This area was under natural fire and drought cycles that preserved its open grassland ecosystems. The monument lies on the outer, southwestern edge of the “Prairie Lake” subregion of the Northeastern Plains, which is characterized by inland lacustrine and riverine drainage systems that once fed both grasslands and wetlands [25]. The ancient heritage cultural landscape of the Pipestone quarries was the product of several Native American tribes who made use of the area, and specifically the pipestone, since A.D. 1400-1450 (Figure 6). These included the Poncas, Omahas, Ioways, Otoes, Sacs, Foxes, and Sioux, although the latter were in control of the Coteau des Prairies by the early 1700s. Sioux interest in the quarries and surrounding region are attested to through migration stories and documented annual pilgrimages to this ceremonial center to obtain pipestone. The Sioux also went there to perform rituals, hold ceremonies, gather plants, and hunt wildlife. Some camp and village sites were established periodically in the region, as were breastworks or enclosures presumed to be defensive structures [24].

Figure 6: Artist’s Rendition of Ceremonial Activity at Pipestone from the Monument Visitor Center

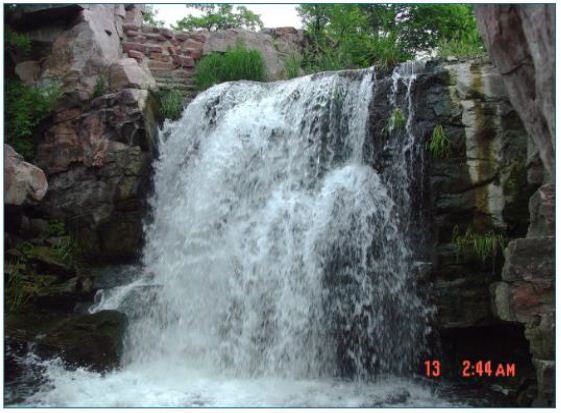

While ceremonial activities may have occurred elsewhere, it seems that the healing and ritual activities primarily involved the water, the waterfalls, and the view of the treeless prairie from the quartzite ridge. Overall, most activities involved one or more of four primary features in the traditional cultural landscape: the waterfalls, the Pipestone quarries, the Three Maidens, and Leaping Rock [5]. The sacred nature of the Pipestone local ceremonial landscape began with medicine plants and rites-of-passage rituals. Then, according to Sioux oral history, White Buffalo Women brought the pipe to the Sioux and the practice of quarrying pipestone began. Native American interpretations and attachments to the place persisted through time, although they became secondary to quarrying the pipestone [5]. The Cree also have oral histories about the sacred pipe and the creation of the catlinite quarry at Pipestone. Catlin [26] recorded one story of a Cree that had visited Pipestone: …in the time of a great freshet, which took place many centuries ago, and destroyed all the nations of the earth, all the tribes of the red men assembled on the Conteau du Prairie, to get out of the way of the waters. After they had all gathered here from all parts, the water continued to rise, until at length it covered them all in a mass, and their flesh was converted into red pipe stone. Therefore, it has always been considered neutral ground – it belonged to all tribes alike, and all were allowed to get it and smoke it together. Catlin documented several tribes’ origin stories of Pipestone. Each attributed the use of Pipestone to multiple groups, and each tribe emphasized Pipestone as a place of peace. For thousands of years, during which Native American people used this ceremonial center, it was primarily a male place where medicine men sought plants for healing, performed rites-of-passage, and pursued vision quests. One such rite involved a four-day submergence in the Pipestone Creek (Figure 7), after which boys became men and could be counted on to have the stamina necessary for hunting and fighting [5].

Figure 7: Winnewissa Falls along Pipestone Creek

Upon arriving at the ceremonial center, they would set up camp away from the quarries. Once greeted by thunder and lightning storms, the men would make ceremonial camps near the Three Maidens and begin to prepare themselves by cleansing in the creek and giving prayers and tobacco offerings at the Three Maidens, which is the gateway into the sacred areas of Pipestone. If thunder and lightning greeted them again, the place had heard their prayers and given them permission to enter the site. If thunder and lightning did not occur, the men may have returned to the ceremonial camp for more preparation or to the main camp to prepare for the return home [5]. Having entered the quarry sites, many of which paralleled the quartzite ridge for nearly a mile, the men who were not quarrying might continue with sweats and prayers until they were needed. Upon entering a quarry, each man would make a tobacco offering to indicate their purity and to protect them while they worked. When they were done, they took the offerings with them to show respect for the spirits of the sacred area [5].

Medicine Wheel/Medicine Mountain Case Two

Medicine Wheel/Medicine Mountain National Historical Landmark (Medicine Mountain) is a large ceremonial center in present day Wyoming (Figure 8). Many Native American groups such as the Arapaho, Bannock, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Crow, Kootenai- Salish, Plains Cree, Shoshone, and Sioux have all come to this area for ritual activity over the course of at least 7,000 years. Medicine men/religious leaders visited the mountain for a range of ceremonial activities related to doctoring and vision questing. During recent ethnographic studies, tribal religious leaders and tribal elders have pointed out that even across the many different groups connected to Medicine Mountain, there is a common and shared understanding of the spiritual and ceremonial importance of this landscape [27,28].

Figure 8: Medicine Mountain Landscape

Medicine Mountain (Figure 9) is at the center of numerous ceremonial trails leading into the area from different directions. Once religious leaders approached the base of the mountain, they would ascend the eastern slope. The trails along the eastern side of the mountain have been interpreted by some Native Americans as being linked to the notion that Medicine Mountain is not just a mountain, but rather it is a spirit lodge in a very literal sense [27-29]. The mountain houses important spirits, and for those visiting the mountain, they must approach it in the same culturally appropriate manner as you would a spirit lodge (Sun Dance or ceremonial lodges). In order to do so, it must be approached from the east.

Figure 9: Medicine Mountain (NPS 2015)

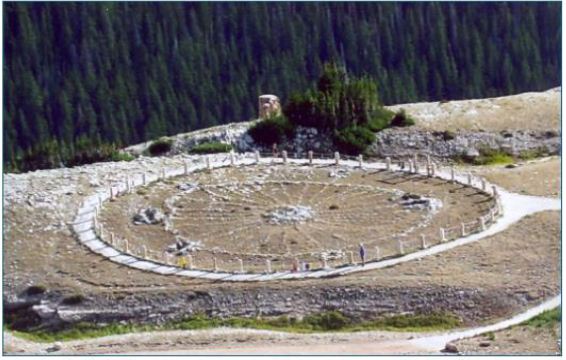

The trails leading up the eastern flank of the mountain are marked with rock cairns surrounded by ritually deposited materials, or offerings. Numerous features are located along the trails up the mountain, such as stone-lined arrow effigies, rock cairns, prayer shrines, patches of medicinal plants, and places for short- and long- term occupancy. When reaching the top of the mountain, religious leaders had access to designated areas for vision questing along the rim [27-29]. The Bighorn Medicine Wheel on the ridge west of the Medicine Mountain summit is the principal ceremonial site (Figure 10). Native Americans have described it as “the altar” for Medicine Mountain. Healing ceremonies for sick individuals who have made the pilgrimage tothe mountain are performed in the northeastern part of the district [27-29].

Figure 10: Bighorn Medicine Wheel

The large medicine wheel at the top of the mountain is also a ceremonial destination place. The medicine wheel has been used for two distinct ceremonial purposes during two time periods. It is believed that Native Americans first used the medicine wheel as a time keeping instrument with a select and highly specialized group of religious leaders involved in time keeping ceremonies. It was likely their pilgrimages to Medicine Mountain occurred at different periods than those for vision quest. At a later point in time, the medicine wheel became an area associated with doctoring ceremonies. During healing ceremonies, balance would be restored to both the patient and the surrounding environment [27-29].

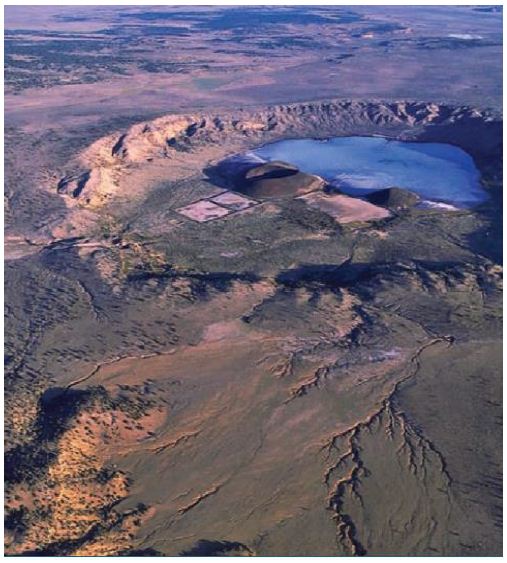

Zuni Salt Lake and Sanctuary Case Three

Located 42 miles south of the Pueblo of Zuni, the Zuni Salt Lake and Sanctuary (Zuni Salt Lake) (Figure 11) is a ceremonial center that is approximately ten miles in circumference. This landscape of origin is on the NRHP as a historic archaeology district rather than a TCP due to the number of inholding private properties. The lake is located in a circular depression and contains a large concentration of salt. The crater was formed by volcanic activity associated with the two cinder cones found at the south side of the lake [30]. People are often drawn to volcanic sites; volcanic activity plays a key role in the development of unique minerals and biotic communities. Volcanoes are seen as special places, especially to Pueblo communities, whose membership often refer to them as Earth Navels [31]. This ceremonial center features in the oral histories of Acoma, Hopi, Laguna, and Zuni. Each pueblo has individual origin stories that account for the lake and the Salt Woman who resides in it. Duff et al. [32] identifies the Salt Woman in each pueblo’s history, known as Ma’lokyyattsik’i to the Zuni, Öng.wùuti to the Hopi, and Mina Koya to Acoma and Laguna (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Zuni Salt Lake Landscape

Stories about Salt Woman have common themes among various Pueblo peoples. Salt Woman took a long journey to each of the tribes before she settled down at the salt lake, and her home can still be identified by the people in these respective locations. While living with the tribes she was not respected: some people wanted her to leave because of her appearance, and some even polluted her home. The Salt Woman eventually left the tribes and traveled east on the back of an eagle where she met Turquoise Man. From there she traveled south, leaving remnants of her travels behind, and eventually settled at the lake (Figure 12) [32].

Figure 12: Ariel View of Zuni Salt Lake (Duff et al. 2008)

Realizing their mistakes, the Pueblos reconnect with the Salt Woman at Zuni Salt Lake by collecting the sacred salt from the lake. Out of respect for Salt Woman, the Zuni Salt Lake area is a conflict-free area. Today, the sacred salt is acknowledged as spiritually important to the people and used for ceremony and healing. The lake is surrounded by prehistoric trails that connect associated Pueblos. Contemporary pilgrimages take these pueblos to Zuni Salt Lake via these trails for ceremony and ritual collecting of this highly valued salt (Figure 13) [32,33].

Figure 13: Aerial View of Zuni Salt Lake Taken from Google Earth

Oday, Zuni Salt Lake is protected by the Pueblo of Zuni. In order to access this sacred location, individuals would have to obtain permissions from governing Pueblo of Zuni officials. According to an elder from the Pueblo of Zuni, the idea of getting permission to visit the site is problematic because all culturally affiliated pueblos have rights to the sacred landscape, not just Zuni [32].

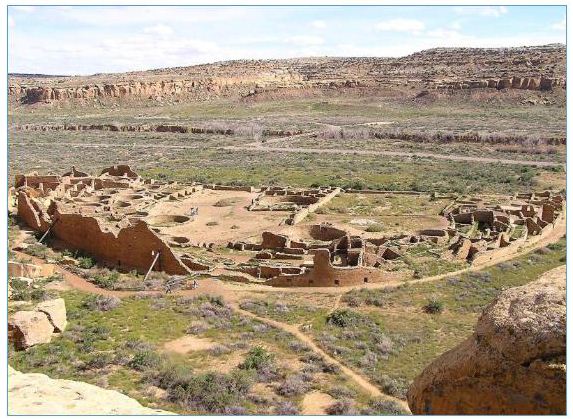

Chaco Culture Case Four

Chaco Culture National Historical Park (Chaco) (Figure 14) is located in the San Juan Basin of the Four Corners region of New Mexico in the Southwestern United States. Chaco is a large regional ceremonial center that builds on complex inter-tribal relationships [34-36]. Numerous Western Pueblo tribes are culturally affiliated with Chaco, including Acoma Pueblo, Hopi Tribe, Nambe Pueblo, Navajo Nation, Pojoaque Pueblo, Santa Ana Pueblo, Santa Clara Pueblo, Santo Domingo Pueblo, Tesuque Pueblo, Zia Pueblo, and Zuni Pueblo [36].

Figure 14: Chaco Landscape

Chaco was a regional pilgrimage center [37] and likely remained a destination of special importance and continued to be visited through pilgrimages after the fall of Chacoan culture [36,37] argue that “undertaking the pilgrimage [to Chaco] was a way to demonstrate one’s commitment to the religious system centered at Chaco and the identity and moral system tied to it.” Connections to distant communities are evident in exotic materials found within the canyon, such as macaw remains, which trace this linkage as far away as Mesoamerica. Much of the ceramics and lithic remains found within Chaco were identified as non-local, and great houses contained hundreds of rooms with sleeping platforms [37]. Estimates put the peak population of Chaco between 2,100 and 2,700. However, construction of structures and agricultural fields at Chaco could have supported much greater numbers [38]; this suggests Chaco served not as a larger pueblo for year-round living but as a ceremonial center for seasonal visitors. Lekson [39] also argues that Chaco served as the regional ceremonial center that was linked to Aztec Ruins and Casas Grandes (Paquimé) through the Chaco Meridian, a longitudinal line at approximately 108 degrees west that connects these three ceremonial centers.

Construction in Chaco suggests a ceremonial use of the great houses (Figure 15) within the area. According to Sofaer [40], “major buildings of the ancient Chacoan culture of New Mexico contain solar and lunar cosmology in three separate articulations: their orientations, internal geometry, and geographic interrelationships.” There are a series of great houses (Figure 15), large multi-level developments, often oriented with solar, lunar, and cardinal directions built within line of site with one another (NPS N.d. a) [41].

Figure 15: The Pueblo Bonito Great House as Seen from a Cliff

A unique system of signal fires connected the great houses of Chaco. Signaling stations played a major role in the organization of Chacoan communities. These stations, which were lit with fires and intensified with reflective materials such as mica or selenite, are located along the roads of Chaco, creating connections between the great houses [42]. Signal fires can have a wide range of purposes, such as for ritual and ceremony, warfare, hunting, scheduling, and even defense [43]. These signal fires are located in high areas with unobstructed views to the next, typically on a tall building or a hill. Selenite, a highly reflective material, was found at some of the signaling sites across Chaco [43]. These signaling stations were capable of quickly carrying information across the canyon to each great house, allowing ceremonies to be conducted simultaneously across the entire region.

Fajada Butte (Figure 16) is a large topographic feature that stands over 400 feet high. It was one of the primary ceremonial destination places for religious leaders who traveled from other Chacoan communities. These journeys would be part of major events that were marked by the Sun Dagger. Also, trips would be made to this area for continuous interactions with the sites and shrines, ceremonies, interactions with other religious specialists to share ideas, and for teaching inexperienced people about time keeping and the movements of the sun, moon, and stars. The Sun Dagger on Fajada Butte is in the southeastern gap of the primary canyon in Chaco, approximately one kilometer to the east of Chacra Mesa (Figure 17). The dagger is formed by three large sandstone slabs that collimate sunlight onto two spirals [44,45]. The slabs result from a natural rock fall, not human engineering. While impossible to date the rock fall and peckings, it can be inferred that ancestral Native Americans carved the spirals after observing the light patterns for numerous annual cycles, thus using naturally occurring patterns and human made alternations to engineer a calendar [36,44].

Figure 16: Fajada Butte

Figure 17: The Sun Dagger Over a Petroglyph at Fajada Butte

Along the predominant ledge just below the Sun Dagger, there are a series of rooms that extend around most of butte. These rooms have been exposed due to erosion processes. In nearly all of the rooms that were visited during the 1994 study, pieces of pottery were found. One of the rooms is circular shaped and visiting tribal representatives believed it to be a kiva. It has been estimated that 20 to 30 rooms were built at this level, and they are believed to be the rooms where time keeping specialists lived during ceremonial activities on the butte [36]. Rooms were used by more experienced specialists to teach newcomers about celestial movements. Near the roofs of these rooms are various calendars and peckings which have been identified as representing clans, origin beings, ancestral beings, and physical representations of time. In accordance with traditional and contemporary use patterns of Pueblo households, theroofs of these rooms were seen as appropriate places to study, teach, and record the movements of the stars, sun, and moon [36].

Sugarloaf Mountain/Goldstrike Canyon

Sugarloaf Mountain/Gold Strike Hot Springs (Sugarloaf Mountain) is the fifth Landscape of Origin to be described and used to compare with Effigy Mounds (Figure 18). Sugarloaf Mountain is a valuable point of comparison because it was the first Native American cultural property that existed in two U.S. states (Arizona and Nevada) to be placed on the NRHP as a Native American TCP. In addition, the Sugarloaf Mountain TCP includes a portion of the Colorado River where Indian people traditionally moved between the hot spring canyon in Nevada and the ceremonial mountain in Arizona (Figure 19). Because Sugarloaf Mountain has been placed on the NRHP, this description uses text from the formal document.

Figure 18: Sugarloaf Mountain Landscape

Figure 19: Sugarloaf Mountain and the Colorado River

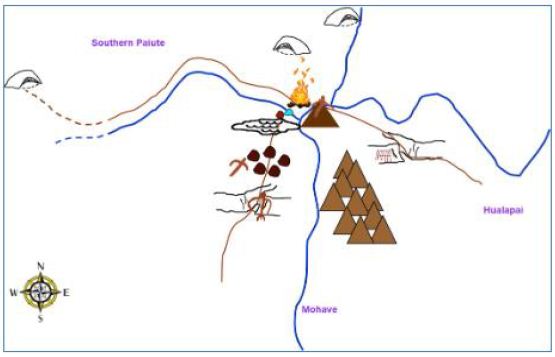

This property (a technical term used in the TCP nomination process) was successfully evaluated as a part of a larger cultural landscape of origin that has significance to a number of Native American tribes in the region. Although the TCP evaluation focused primarily on the mountain and the hot spring canyon located just across the Colorado River to the west, its cultural significance is, in large part, determined by its place within this larger landscape of origin setting. The Southern Paiutes, Hualapais, and Mohaves have all traditionally used Sugarloaf Mountain as a place for practicing spiritual, scientific, educational, political, economic, and social activities. The long-term presence of Native Americans at Sugarloaf Mountain is evidenced by physical artifacts that include two noticeable demarcated ceremonial clearings, apetroglyph, a turquoise mine at the base of the mountain, a cave with grindstones for corn or paint, small healing rocks, and several lithic scatters [46]. In addition to archeological evidence, historical and contemporary documentation confirms the existence of strong connections between Sugarloaf Mountain and the Southern Paiutes, Hualapais, and Mohaves. These intimate and deeply forged connections to Sugarloaf Mountain are integral to the maintenance of cultural, spiritual, ecological, and historic continuity between the ancient people of southern Nevada and their contemporary descendants. Today, the preservation of sacred knowledge and traditional cultural practices through the education of young people hinges upon the recognition and protection of those sacred places of the Southern Paiutes, Hualapais, and Mohaves that have not been irrevocably altered. Sugarloaf Mountain is such a place [46]. Amongst the Mohaves, Sugarloaf Mountain is repeatedly mentioned as a place that is tied to the sacred mountain, Avikwame. In travel songs, bird songs, and celebratory songs, Sugarloaf Mountain is noted as the northern most boundary as well as a spiritual place of power, which islinked to the Origin Mountain, Avikwame. The Hualapais also experience enduring connections to Sugarloaf Mountain. Upon arriving to Sugarloaf Mountain, one Hualapai elder began to speak in the cry voice about that which came before. In the presence of the mountain, she re-experienced the memories of her ancestors whose presence at Sugarloaf remains strong. She relayed how elders, adults, youths, and babies were forced to leave their ancestral lands and march to La Paz. Many were shot, thrown into pits full of slain humans, and even buried alive. Hualapai women and children were frequently killed alongside Hualapai men. Those who were not shot often died of European diseases and starvation. Today the Hualapai meet each year to conduct a three-day ceremony to mourn and honor the people who died on the march to La Paz [46]. The Southern Paiutes also experience intimate connections with Sugarloaf Mountain. According to several elders, Sugarloaf Mountain is on the Salt Song Pathway to the afterlife. Although first recorded at the turn of the century, the Salt Songs have their origins in times before Euro-American histories. The Southern Paiutes continue to sing the Salt Songs today. As a result, the sacred places that are mentioned in these songs remain central to Southern Paiute identity and culture. This is confirmed in ethnographic interviews. The elders explained that “Sugarloaf is a sacred place to Southern Paiutes. It is the only place of its kind that is used as a path to communicate with spiritual beings in the area” [46]. In addition, “The doctor rocks, crystals, and offering places in this area were placed here by the Creator for Southern Paiutes and others” [46].

Since time immemorial, Southern Paiutes, Hualapais, and Mohaves have practiced cultural observances at Sugarloaf Mountain. On the top of Sugarloaf, individuals and shamans used the ceremonial clearings for spiritual purposes, astronomical observances, teaching, and both political and social gatherings. The base of Sugarloaf Mountain has frequently been used in connection with healing activities utilizing doctor rocks, plants, and whiptail lizards [46]. Today Sugarloaf Mountain is integral to the maintenance and perpetuation of the cultural traditions of the Southern Paiute, Hualapai, and Mohave. This sacred place serves as a location where cultural traditions and knowledge can be conveyed from generation to generation. As there are many factors that endanger the cultural traditions of these groups, it is essential to protect and preserve Sugarloaf Mountain so that it may continue to play its critical role in the transmission of knowledge from elders to youths. Many elders agree that Sugarloaf Mountain is “a good place to teach children and let them understand better what it’s all about” [46]. Sugarloaf Mountain has always been a ceremonial destination place where individuals, medicine men/ religious specialists, and healers have gone to develop and practice their knowledge. Amongst the Southern Paiutes, Sugarloaf Mountain has served as an area where people have gone to educate and prepare themselves for sacred ceremonies occurring at Gypsum Cave. Sugarloaf Mountain has also served as a community learning center. “The old people used to meet here with the Hualapais, Chemehuevi Paiutes, Moapa Paiutes and others for spiritualpurposes,” [46]. In addition, Sugarloaf Mountain has traditionally served as “a place away from main villages, where people came to talk about common interests,” [46]. Today the Southern Paiute, Hualapai, and Mohave express a unified desire to maintain these practices and thus ensure their knowledge and traditions will be kept alive and rejuvenated amongst younger generations [46]. The following are discussions of specific key cultural components of Sugarloaf Mountain as a TCP which is located within a larger Landscape of Origin. Figure 20 is a representation of the Sugarloaf landscape with the three pilgrimage trails marked in brown.

Figure 20: Diagram of Sugarloaf Mountain Pilgrimage Trails and Associated Features

A Landmark

Sugarloaf Mountain has been used as a landmark as well as a ceremonial center for the exchange of knowledge over thousands of years. This knowledge comes from elder teachers as well as the mountain itself, which the Southern Paiute, Hualapai, and Mohaves have been taught to attune themselves towards, and thus accrue knowledge from multiple rather than singular educational sources. As much of this knowledge is learned directly from the mountain itself, this place is integral to cultural traditions [46].

A Ceremonial Area

The ceremonial activities constitute one of the central functions of Sugarloaf Mountain. These activities involved both individual shamans and groups of people who regularly convened on Sugarloaf Mountain to worship, develop knowledge, and express knowledge through healing practices. These activities included astronomical observations, rituals, vision quests, and the collective augmentation of knowledge [46].

Vision Questing Area

Sugarloaf Mountain also served as a location for vision quests that sometimes involved both individuals and whole families. These vision quests occurred at Sugarloaf Mountain because it was a known center of power. Today this same power is acknowledged and understood by the Southern Paiute, Hualapai, and Mohave elders. The recognition of this power explains their need to teach their children at this location [46].

A Healing Area

Sugarloaf Mountain has always played an integral role in the healing traditions of the Southern Paiute, Hualapai, and Mohave. In both prehistoric and historic times successful healing required an in-depth knowledge of the healing resources provided at Sugarloaf Mountain, as well as a respectful relationship with this source of power. The power of Sugarloaf Mountain helped them to prepare themselves for receiving the songs necessary for healing, as well as the knowledge to utilize the water, doctor rocks, lizard tails, plants, and regions of healing in a manner conducive to physical and spiritual restoration [46].

An Area for Ceremony and Intertribal Gatherings

Sugarloaf Mountain has been repeatedly noted as a place of power. Those who gathered at Sugarloaf Mountain did so under varying circumstances. Frequently, the gathering focused on spiritual and educational purposes, which speaks to the focus on events that contributed to cultural continuity. It is suggested in interviews that Native Americans gathered at Sugarloaf Mountain under political pretenses including the Ghost Dance. Therefore, the ceremonial clearings had multiple functions [46].

A Component of a Cultural Landscape

Sugarloaf Mountain expresses its power through all of the elements of nature, which are understood to manifest in concert rather than as discrete entities. Sugarloaf Mountain exists as a place of power within a larger plane of interconnections. Tribal representatives noted that it is related to other significant places including Gypsum Cave and Avikwame. Sugarloaf Mountain has functions and uses that are simultaneously unique yet integrally related to places beyond itself. The cultural features/elements found at Sugarloaf Mountain are part of a larger cultural entity, preserving the larger traditions of multiple ethnic groups. The mountain and its natural/cultural elements are a significant part of a cognized landscape important to tribes in the region. From the top of Sugarloaf Mountain, the people who frequented this place had a viewscape that connected the mountain and its people to the four directions and the sacred places noted in both songs and oral histories [46].

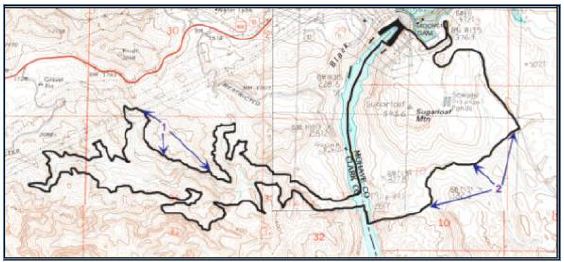

A TCP with Continued Cultural Centrality

The Southern Paiutes, Hualapais, and Mohaves are invested in protecting and continuing their relationships with Sugarloaf Mountain because it is a ceremonial place in a landscape of origin and a significant source of knowledge and power. The designated boundaries of the TCP are shown in Figure 21. This power does not express itself in a unilinear fashion, wherein only humans benefit. Instead, the Southern Paiutes, Haulapais and Mohaves strive to create relationships that are mutually respectful, knowledge-based, and balanced [46].

Figure 21: Sugarloaf Mountain TCP Boundaries (Stoffle et al. 2000)

The Southern Paiute, Hualapai, and Mohave elders repeatedly voiced the need to bring their youth to Sugarloaf Mountain. This desire stems from the power of the place, as well as the educational process that has always played a primary function at this sacred landscape.

Discussion

These six case studies are comparable examples of geoparks in Landscapes of Origin. The purposes and uses of these places were different from place to place, however, there are distinct similarities. Numerous Native American tribes connected to these geoplaces have used these ceremonial centers for thousands of years. The connections that these groups have to these landscapes are complex and layered, and shift throughout time. Sacred connections to these areas are culturally significant to many different Native American people.

Landscapes of Origin – Creation

Common themes exist between these ceremonial centers and Effigy Mounds. One example is the connections made through origin stories. Places like Zuni Salt Lake, Chaco, and Pipestone are associated with multiple origin stories from surrounding Native American tribes. At Zuni Salt Lake, Salt Woman, the creator being that resides in the lake, features in the origin stories of Zuni, Acoma, Hopi, and Laguna. Furthermore, she continues to serve an important role in their cultures by providing salt to the associated Pueblos. Similarly, affiliated Pueblo groups have creation stories that tell of clan migrations through Chaco. At Pipestone, Sioux accounts attribute the creation of Pipestone to White Buffalo Woman, while Cree accounts associate the place with a great flood and the coming together of many different ethnic groups. Similarly, culturally affiliated tribes at Effigy Mounds have origin stories that link clan migrations to specific mound groups within the monument.

Landscapes of Origin – Ceremony

There are parallels between ritual activities conducted at Effigy Mounds and previously discussed ceremonial centers. For example, Effigy Mounds, Chaco, and Medicine Mountain have features used in time keeping ceremonies. Activities that occur at these three ceremonial centers are linked to solar and lunar observations made by religious leaders of the community. Tracking time was used for a range of activities including agriculture, pilgrimage, and balancing ceremonies. Chaco, a pilgrimage destination place, housed religious leaders from across the region to conduct large scale ceremony involving solar and lunar observations at Fajada Butte. Religious leaders were positioned throughout the canyon to conduct simultaneous ceremonies, which were coordinated through signal fires. Medicine Mountain also had a time keeping component; the medicine wheel itself was a calendar used to track the passage of time. Other ceremonies at Medicine Mountain involved healing and vision questing. At Effigy Mounds, a linear mound at the Marching Bear Group lines up perfectly with the sun during the summer solstice, similar to the structures across Chaco or the spokes of the Bighorn Medicine Wheel. Locations along the bluffs of Effigy Mounds and surrounding areas, such as Pikes’ Peak, contained evidence of fire use, which was used potentially to coordinate a region-wide simultaneous ceremony.

Landscapes of Origin – Pilgrimage

Pilgrimage is the third common theme among the landscapes of origin discussed in this article. Pilgrimages to these sacred landscapes involved patterned movements along predetermined routes and trail networks. The movement of people along these routes were part of the ceremonies themselves. Religious specialists traveled great distances to engage with these landscapes. Along the trails, the specialists (also referred to as pilgrims) visited shrines, leaving offerings and saying prayers. These acts provided the pilgrims with knowledge they needed to continue with their journeys. The six (6) case studies have well defined and understood trail systems that lead to the ceremonial destination places from the various home communities of the connected ethnic groups. For example, at Sugarloaf, Southern Paiute religious specialists traveled along trails from the west, Mohave people traveled from the south, and Hualapai traveled from the east to reach the mountain. The trails to Sugarloaf share similar features and places of prayer; along these trails a similar pecked figure is found, which is also found on the top of Sugarloaf Mountain. At Medicine Mountain, pilgrimage trails lead to the mountain from all directions, however these trails all come together at the base of the eastern slope of the mountain. All religious specialists seeking to engage the Medicine Wheel for ceremony must approach it from an easterly direction in a manner that parallels how one enters a medicine lodge. Effigy Mounds is a known destination place for many different ethnic groups, which would have used unique land and water trails to approach this scared landscape. River navigation likely played a key component in pilgrimage. Religious specialists would have canoed down the Mississippi, Wisconsin, and Yellow Rivers to reach their destination.

Landscapes of Origin – Conflict Free Zones

An important component of landscapes of origin in Native North America is the multi-ethnic use/neutral component to these places. Places, such as Pipestone and the Zuni Salt Lake, are well documented as playing an important role in the ritual, ceremony, and pilgrimage of multiple affiliated tribes and pueblos who have a shared use of the place and its resources. Pipestone and Zuni Salt Lake’s origin narratives indicate that the neutrality of the place is a part of respecting the creator being that resides in the landscape. Multiple narratives account for the multi-ethnic use of Pipestone, many of which were documented by Catlin [26] during his visit to Coteau des Prairie, though the territory was controlled by the Sioux during his travels. Similarly, Nicollet wrote about Pipestone being a place of peace that was visited at different times of the year by different tribes [47]. Zuni Salt Lake has an identified Sanctuary, 182,000 acres approximately ten miles around the lake, which was added to the NRHP. The area includes pilgrimage trails and religious shrines that play important roles in the ritual use of Zuni Salt Lake. This area is traditionally void of any violence out of respect for the Salt Woman [32]. The bluffs of Effigy Mounds were central to the ceremony conducted by multiple visiting Native Americans, but likely they were a part of a greater landscape that extended along the Mississippi River and across the river in Prairie du Chien, which was a documented trading hub and ceremonial center for visiting tribes. In order not to disrupt ceremonies at the mounds or the economic and cultural ties between these groups, this area would similarly be declared neutral grounds rooted in the creation narratives of the landscape. The common themes that have been highlighted throughout this analysis show that multi-ethnic ceremonial centers exist in Native North America, exist because of special geological features, and have ritual and cultural-historical components to them. Effigy Mounds fits into the definition of a multi-ethnic ceremonial center, because Native Americans have long-term spiritual connections to the mounds and the mounds serve as physical links to Creation stories. While the uses of Effigy Mounds are tribal and place specific, the broader pattern of this ceremonial center is found elsewhere. Like the five Zuni Salt Lake, Medicine Wheel, Chaco, and Sugarloaf Mountain, Effigy Mounds continues to hold cultural meaning and spiritual importance to contemporary tribal peoples.

References

- Brocx Margaret, Vic Semeniuk (2024) Geoparks, Geotrails, and Geotourism – Linking Geology, Geoheritage, and Geoeducation. Special Issue of Land. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute.

- Christie Jessica (2009) Landscapes of Origin in the Americas: Creation Narratives Linking Ancient Places and Present Tuscaloosa: University Alabama Press.

- Barth Fredrik (1969) Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture

- Stoffie RichardW, Kathleen A. Van Vlack, Richard W Arnold (2006) Paa’oasta Hunuvi: Water Bottle Canyon Traditional Cultural Property Study Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson.

- Toupal Rebecca S, Richard W Stoffie, Nathan O’Meara, Jill Dumbauld (2004) Takuśkaŋśkaŋ Ćaŋnomoke: The Everchanging Pipestone Quarries Sioux Cultural Landscapes and Ethnobotany of Pipestone National Monument, Minnesota. Prepared for the National Park Tucson, AZ: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona.

- Howey Meghan CL (2012) Mound Builders and Monument Makers of the Northern Great Lakes, 1200-1600. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Dillehay Tom (2007) Monuments, Empires, and Resistance: the Araucanian Polity and Ritual Narratives Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Smith, David Lee (1997) Folklore of the Winnebago Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Hicks, Dan, Laura McAtackney, and Graham Fairclough. 2007. Envisioning Landscape: Situations and Standpoints in Archaeology and Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Stoffie Richard W, Rebecca S Toupal, Nieves Zedeño (2003) Landscape, Nature, and Culture: A Diachronic Model of Human-Nature Adaptations. In: Nature Across Cultures: Views of Nature and the Environment in Non-Western Cultures. Pg: 97-114. Helaine Selin, editor. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Anyon, Roger, T.J. Ferguson, Loretta Jackson, and Lillie Lane. (1996) Native American Oral Traditions and Archaeology. SAA Bulletin 14(2)

- Basso Keith H (1996) Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apache. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

- Deloria Vine (2003) God is Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Press.

- Turner Victor (1974) Pilgrimage and Studia Mssionalia. 23: 305-327.

- Van Vlack, Kathleen, Richard Stoffie, Evelyn Pickering, Katherine Brooks, Jennie (2013) Unav-Nuquaint: Little Springs Lava Flow Ethnographic Investigation. Prepared for the National Park Service. Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson AZ

- Van Vlack Kathleen. (2012) Puaxant Tuvip: Powerlands Southern Paiute Cultural Landscapes and Pilgrimage Trails.

- Van Vlack, Kathleen (2012) Southern Paiute Pilgrimage and Relationship Journal of Ethnology 51: 129-140.

- Van Vlack, Kathleen (2018) Puha Po to Kavaicuwac: a Southern Paiute Pilgrimage in Southern International Journal of Intangible Heritage. 129-141.

- Van Vlack Kathleen (2022) Dancing with Lava: Indigenous Interactions with an Active Volcano in Arizona. In Anthropological Perspectives on Environmental Edited by A. Sjölander Lindqvist. London: Pelgrave MacMillian. Pg: 29-53.

- Stoffie Richard, G Rogers, F Grayman, G Bulletts-Benson, K Van Vlack, J Medwied- Savage (2008a) Timescapes in Conflict: Cumulative Impacts to a Solar Calendar. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 26: 209-218.

- Thwaites Reuben G (1888) Collections of the State Historical Society of Madison, WI: Democrat Printing Company, State Printers.

- Blaine, Martha Royce (1995) The Ioway Indians. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Ho Chunk Nation (2015) Timeline of Ho-Chunk Ho-Chunk Nation.

- Zedeño, Maria Nieves, Chrisopher Basaldu (2004) Pipestone National Monument, Native American Cultural Affiliation and Traditional Association Study. Prepared for the National Park Service. Tucson, AZ: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona.

- Anfinson Scott F (1997) Southwestern Minnesota St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

- Catlin George (1841) Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians (1832-1839) 2 Volume II. Minneapolis, MN: Ross and Haines, Inc.

- Boggs James P (1997) Medicine Mountain Ethnographic Project. Report on file, USFS Bighorn National Forest, Sheridan, Wyoming and Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office, Cheyenne.

- Boggs James P (2003) Medicine Mountain and the Bighorn Medicine Wheel between Two Worlds: A Native American Cultural Landscape in Twenty-First Century North Report on file, USFS Bighorn National Forest, Sheridan, Wyoming and Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office, Cheyenne.

- Simmons Thomas, R Laurie Simmons (2009) Medicine Mountain National Historic Landmark Nomination, Big Horn National Forest, Wyoming. Prepared for United States.

- Cummings David (1968) Geologic Map of the Zuni Salt Lake Volcanic Crater, Catron County, New Mexico. Washington D.C.: USGS.

- Ortiz Alfonso (1969) The Tewa World: Space, Time, Being, and Becoming in a Pueblo Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

- Duff Andrew I, TJ Ferguson, Susan Bruning, Peter Whitely (2008) Collaborative Research in a Living Landscape: Pueblo Land, Culture, and History in West-Central New Mexico. Archaeology Southwest 22.

- Ferguson TJ, Kurt Dongoske, Leigh Jenkins, Mike Yeatts, Eric Polingyouma (1993) Working Together: The Roles of Archaeology and Ethnohistory in Hopi Cultural CRM 16, Special Issue: 27-37.

- Cameron, Catherine M, H Wolcott Toll (2001) Deciphering the Organization of Production in Chaco Canyon. American Antiquity 66: 5-13.

- Schillaci, Michael A (2003) The Development of Population Diversity at Chaco Kiva. 68(3): 221-245.

- Stoffie Richard W, Michael J Evans, M Nieves Zedeño, Brent W Stoffie, Cindy J. Kesel (1994) American Indians and Fajada Butte: Ethnographic Overview and Assessment for Fajada Butte and Traditional (Ethnobotanical) Use Study for Chaco Culture National Historical Park, New Tucson, AZ: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona.

- Kantner John, Kevin J Vaughn (2012) Pilgrimage as Costly Signal: Religiously Motivated Cooperation in Chaco and Nasca. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 31: 62-82.

- Lekson Stephen H, William B Gillespie, Thomas C Windes1(986) Great Pueblo Architecture of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Lekson Stephen H (1999) The Chaco Meridian: Centers of Political Power in the Ancient Southwest. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Sofaer A (2007) The Primary Architecture of the Chacoan Culture: A Cosmological In The Architecture of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Stephen H. Lekson (ed.) University of Utah Press

- N.d. History & Culture. National Park Service.

- Lekson Stephen H (2006) The Archaeology of Chaco Canyon: An Eleventh-century Pueblo Regional Santa Fe, N.M: School of American Research Press.

- Swanson Steve (2003) Documenting Prehistoric Communication Networks: A Case Study in the Paquimé Polity. American Antiquity 68: 753-767.

- Newman EB, KR Mark, R G Vivian (1982) Anasazi Solstice Marker: The Use of a Natural Rockfall. Science. 217: 1036-1038.

- Sofaer A, RM Sinclair, L Doggett (1982) Lunar Markings on Fajada Butte, Chaco Canyon, New Archaeoastronomy in the New World, edited by A. F. Aveni, pp 169- 181. Cambridge University Press.

- Stoffie, Richard , Maria Nieves Zedeño, A. Eisenberg, Rebecca Toupal, A. Carroll, F. Pittaluga, et al. (2000) Ha’tata (The Backbone of the River): American Indian Ethnographic Studies Regarding the Hoover Dam Bypass Project. Tucson, AZ: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona.

- Bray Edmund C. Martha Coleman Bray (1976) Toppling of Rock Slopes. Proceedings of the Specialty Conference on Rock Engineering for Foundations and Slopes. 2: 201-234.