DOI: 10.31038/CST.2019415

Abstract

The dramatic worldwide increase in use of smartphones has prompted concerns regarding potential carcinogenic effects of exposure to RFM-EF (Radiofrequency-Modulated Electromagnetic Fields). Previous studies indicated epidemiologic evidence for many risks arising from exposure to smartphones. Despite this growing evidence, the exposure to smartphones is rising across age groups. This study identified communication messaging which increases awareness of risks, and convinces the respondent of the seriousness of these risks. We revealed two mind-set segments (Focus on Work; Focus on Safety) illustrated how to use our viewpoint identifier tool to assign the belonging of a people in the population into mind-set segments.

Introduction-what we know about health risks and smartphones?

The evolving capabilities of cell phones have extended beyond their initial purpose turning them into vital and indispensable communication tool with increasing features mimicking other technologies [1]. The dramatic worldwide increase in use of cellular telephones has prompted concerns regarding potential harmful effects of exposure to radiofrequency-modulated electromagnetic fields, particularly a concern about potential carcinogenic effects from the RF-EMF emissions of cell phones [2].

Certain electromagnetic fields at low frequency have been recognized as possibly carcinogenic by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [3]. Since 1992, our world has become suffused with cellphones facilitating social interactions. Use of cell-phones for communication seems to rule our daily lives, at school [4], while driving [1,5], at work, and around the dinner table. This widespread use is growing into a common point of discussion generating concerns about potential risk hazards.

Cancer has been suggested as an outcome of exposure to mobile telephones by some scientific reports leading the WHO to address key issues [6]. A study that evaluated the link between the use of smartphones and the development of types of cancer tumors on the head (gliomas, meningiomas and neuromas of cranial nerves) in 13 countries suggested a general tendency for an increased risk of glioma among the heaviest users: long-term users, heavy users, users with the largest numbers of telephones [3]. Text messaging using smartphones after one year among 7092 people ages 20–24 was reported to increase symptoms in neck and upper extremities [7]. In healthy participants and compared with no exposure, 50-minute cell phone exposure was associated with increased brain glucose metabolism in the region closest to the antenna [8].

Another study that compared among areas of exposure to cell-phone transmitter stations indicated a significant increase in incidents of cancer for those living in proximity to the stations [9]. Moreover, a report based on an international research and public policy aimed at an overview of what is known regarding biological effects of low-intensity electromagnetic exposure shows that this exposure is associated with a wide array of problems. Following is a list of some of the more common problems: childhood leukemia, brain tumors, genotoxic effects, neurological effects and neurodegenerative diseases, immune system deregulation, allergic and inflammatory responses, breast cancer, miscarriage and some cardiovascular effects concluding that a prolonged exposure carries a reasonable risk [10].

Smartphone usage has also been associated with psychological health effects. Heavy use was associated with high anxiety and insomnia [11]. Among young adults prolonged use of smartphones has been reported to increase stress, sleep disturbances, and symptoms of depression [12]. Also, in a study testing the effect of smartphone use on adolescents’ well-being a pattern of heavy use was reported to negatively affect mental health (i.e., aggressive behavior, biased gender roles, disturbances in body image, obesity, and even substance use) [13].

As the debate regarding health risks of low-intensity electromagnetic radiation from smartphones, has been reignited, a meta-analysis reviewed the existence of an epidemiologic evidence for the association between long-term usage of smartphones and the risk of developing a brain tumor [14]. Their results indicated that there is adequate epidemiologic evidence. Usage of a smartphone for ≥10 years approximately doubles the risk of being diagnosed with a brain tumor on the same side of the head as the side preferred for smartphone use.

Another heath risk is related to the smartphone surface as contaminated. A study that tested smartphone as a source for bacterial contamination on the smartphones of physicians at hospitals and found that 83% of surgeons had a high rate of pathogenic bacteria and organic material contamination [15].

The focus of this paper is the identification of communication messaging regarding dangers in extensive use of smart phones. What messaging communicates the dangers involved in the user behavior of smartphones? Launching this research project and reading the literature, led to the realization that there are two dimensions, quite different from each other. The first dimension is BELIEVABLE. Is the message one that can be believed, or is it disregarded? The second dimension is BAD. Does the information convey a fact which is perceived to be associated with damage, specifically damage to health?

The answer our question regarding the representative messaging to communicate the danger might seem simple, but as we will see, it is not. A respondent might either feel that the message is not as bad as one thinks, or worse, that the message talks about something bad, but the message is simply not true [16].

Method

We used the emerging science of Mind Genomics to quantify the perceived believability and the perceived ‘badness’ of messages about cellphone use and what it does to people. We began with a series of six questions shown in Table 1. For each of the six questions, we created six fact-based answers, culled from various sources. Whether the facts culled from the sources could themselves be demonstrated to be real or simply exaggeration was not of interest. We focus here on aspects of argumentation, on what is perceived to be believable, and what is perceived to be ‘bad,’ rather than establishing the validity of statements in a nation-wide validation of the messages.

Table 1. The six questions, and the six answers to each question about cell phones

|

Question 1: What are the uses of cellphones? |

|

|

A1 |

Cell phones let you stay in touch with your loved ones at all times |

|

A2 |

Cell phones let you stay connected to work |

|

A3 |

Cell phones keep you in touch with your email wherever you go |

|

A4 |

Cell phones let you text each other whenever you want |

|

A5 |

Cell phones let you stay in touch with your child(ren) at all times |

|

A6 |

Cell phones give you a personal sense of security |

|

Question 2: How do cellphones help you with your family? |

|

|

B1 |

Cell phones let you to know where your kids are at all times |

|

B2 |

Cell phones give your family ability to reach you at any time |

|

B3 |

Cell phones give your kids the ability to reach you whenever they need you |

|

B4 |

Cell phones make it easier to pick up your kids from school and school events |

|

B5 |

Cell phones make travel easier |

|

B6 |

Cell phones make it easy to pick up people at the airport |

|

Question 3: How do cell phones let you work anywhere, and be anywhere? |

|

|

C1 |

Cell phones let you reach anyone anytime you want |

|

C2 |

Cell phones make it easy to work at home |

|

C3 |

Cell phones make it easy to work outside the office |

|

C4 |

Cell phones give you the ability to reach anyone in an emergency |

|

C5 |

Cell phones allow you to be reached by friends or family in an emergency |

|

C6 |

Cell phones are so versatile that they have become indispensable |

|

Question 4: What negative health effects come from using cellphones? |

|

|

D1 |

Cell phones emit radiation whenever they’re turned on |

|

D2 |

Cell phones can be dangerous when driving |

|

D3 |

Cell phones are so light and portable so you can take them anywhere |

|

D4 |

Cell phone radiation is a suspected cause in neurological impairments in children including autism |

|

D5 |

People with higher peak exposures to cell phone radiation have an 80 percent increase in the risk of miscarriage |

|

D6 |

Brain cancer is directly linked to the exponential increases in cell phone use and other wireless devices |

|

Question 5: How has cellphone use changed over the years? |

|

|

E1 |

The manual for every cell phone and smartphone sold in the world instructs users to NOT allow their phones to actually touch their ears! |

|

E2 |

All cell phone manuals instruct users to NOT allow their phones to touch their heads! |

|

E3 |

The tests showing cell phones to be safe are based on how people used cell phones 35 years ago–not the way you use them today! |

|

E4 |

Believe it or not–cell phones have never been safety tested among children and teens |

|

E5 |

Today you use your cell phones far more frequently than you did in the 1980’s when they were safety tested |

|

E6 |

People using cell phones for 2000 hours have 240% greater risk for malignant brain tumors |

|

Question 6: What are other diseases and negative effects of cellphones? |

|

|

F1 |

Cell phone radiation has been shown to cause short term memory loss as well as Alzheimer’s |

|

F2 |

A comprehensive study in Sweden indicates that children and teens are 5 times more likely to get brain cancer if they use cell phones |

|

F3 |

Cell phone radiation has been linked to sterility in males who keep their phones in their front pants pockets |

|

F4 |

Cell phone radiation has been linked to breast cancer in women who carry their phones in their brassieres |

|

F5 |

People have twice the risk of developing the cancer known as “Glioma”, if they use their cell phones for half an hour a day for more than a decade |

|

F6 |

Over the past two years there’s been a 4-fold increase in malignant tumors of the parotid gland on the same side of the face that cell phone users hold their phone |

The strategy of asking questions and providing several answers to each question comes from the world of rhetoric and argumentation [17]. The rationale for the approach is that the questions tell a story, creating a framework by which on can provide different answers which can be substituted for each other.

The answers or answers within a single question may or may not contradict each other. The answers to different questions (i.e., the elements in different silos) may contradict each other in reality, but do not contradict each other logically. In some cases, an element is put into a category which might seem to be inappropriate (e.g., D3 Cell phones are so light and portable so you can take them anywhere), made into an answer for Question 4: What negative health effects come from using cellphones?) The rationale is that the element was important, but there was no place in the most proper silo, and so the element was placed in another, some-related silo.

It is important to recognize that the questions and answers, silos and elements, are simply a device for bookkeeping. When it comes to modeling, there is no recognition of silos at all. All 36 elements are independent predictor variables. It makes no difference to the modeling about the question or silo with which the answer or element is associated

The premise of Mind Genomics is that we learn a great deal about the responses to the elements by presenting combinations of the elements (answers) in short, easy-to-read test concepts called vignettes. In this study, we used six questions, six answers per question, calling for 48 vignettes. Each vignette is incomplete, comprising either four answers (one answer from each of four questions), and comprising three questions (one answer from each of three vignettes.).

The combinations are not created in a random fashion, although to many respondents evaluating the set of 48 combinations it must seem that the combinations are simply created by throwing the elements together. Nothing can be further from the truth. The experimental design underlying the combinations is created so that each respondent evaluates exactly 48 unique combinations, and that the 36 elements are statistically independent of each other. The specific combinations of vignettes vary from respondent to respondent by a simple permutation system which maintains the underlying structure but changes the composition of each vignette [18] This systematic permutation enables the researcher to test many different combinations of the full set of possible combinations. Without a systematic permutation, the researcher would be left with one set of 48 combinations to represent the many thousands of possible combinations. The limited choice would probably generate far more errors because one would have to be quite knowledgeable to know what combinations to test before the experiment begins, were one limited to a single set of predetermined combination. In effect, the traditional approach of testing mixtures requires that the answer be somewhat ‘known’ before the experiment, in order to select the ‘right combinations.’ In contrast, Mind Genomics needs no such knowledge, because across the set of respondents and with 48 vignettes per respondent, the experiment tests many of the possible combinations, at least once.

The rating scale

The vignettes present the information, but they do not focus the respondent’s mind on specifically what should be the judgment criterion. The rating scales, presented at the bottom page of each vignette, focus the respondent’s mind. The first scale instructs the respondent to rate ‘believability.’ The second scale instructs the respondent to rate ‘badness.’ We see the scales laid out in Table 2. The scales are so-called Likert scale, anchored at the lowest, e and highest scale points for ‘believable’, and at the lowest, middle, and highest scale point for ‘bad.’

Table 2. The two ratings scales

|

How much do you believe what you read here? |

|

1 = do not believe at all…..9 = totally believe |

|

Overall how much good to bad do you see in this combination? |

|

1 = all good…… 5 = about half good/half bad…… 9 = all bad |

Running the study

The study was run through a company specializing in on-line recruiting of respondents. During the past two decades running studies on-line has become the preferred, cost-effective way of acquiring data of the type acquired here. The study can be considered as an on-line experiment, with respondents invited to participate. The respondents are incentivized by a point system, with the points given for participation.

The respondents were invited to participate. The respondent who agreed simply clicked on a link embedded in the email which solicited participation. The respondent was presented with an orientation page, shown in Table 3. The respondent read the orientation page, which described the topic, and presented the scales. The respondent then evaluated a unique set of 48 vignettes, rating each vignette first on ‘believability’ and then second on ‘good to bad’. The respondent finished by completing a short, self-profiling questionnaire, dealing with gender, age, education, income, the nature of how the respondent uses cell phones, and how often. The first part of the study, the evaluation of the 48 vignettes, comprises the ‘experiment.’ The second part of the study, the self-profiling classification, comprises the more traditional questionnaire used in consumer research.

Table 3. The orientation page

|

Cell phones have been around for 40 years. The cell phone provides many conveniences in our life. Up to 2013 cell phones were considered safe. During the past two years a number of studies have shown links to various issues worldwide associated with cell phones. We want to how YOU feel about some of these benefits and these issues. You will be reading short ‚press releases,‘ comprising several elements. Think of this press release as a totality, as one complete message that you might read somewhere. For each ‚press release‘ please rate the combination on two aspects: |

|

How much do you believe what you read here? 1 = not at all…..9 = totally believe |

|

Overall how much good or bad do you see in this combination? 1 = all good….. 5 = about half good/half bad…..9 = all bad |

Table 3. How the 36 elements drive believability (Q#1) & perception of ‘bad for you’ (Q#2)

|

Total Panel (n=304 respondents) |

Believe |

Bad |

|

|

Additive constant |

59 |

56 |

|

|

Elements that are believed |

|||

|

D2 |

Cell phones can be dangerous when driving |

12 |

-2 |

|

C2 |

Cell phones let you reach anyone anytime you want |

11 |

-16 |

|

D3 |

Cell phones are so light and portable so you can take them anywhere |

9 |

-11 |

|

C6 |

Cell phones allow you to be reached by friends or family in an emergency |

8 |

-17 |

|

Elements that are perceived to be bad for you |

|||

|

E6 |

People using cell phones for 2000 hours have 240% greater risk for malignant brain tumors |

-13 |

8 |

|

D6 |

Brain cancer is directly linked to the exponential increases in cell phone use and other wireless devices |

-14 |

7 |

|

F2 |

A comprehensive study in Sweden indicates that children and teens are 5 times more likely to get brain cancer if they use cell phones |

-25 |

7 |

|

Neither believed nor bad |

|||

|

D5 |

People with higher peak exposures to cell phone radiation have an 80 percent increase in the risk of miscarriage |

-19 |

6 |

|

F5 |

People have twice the risk of developing the cancer known as “Glioma”, if they use their cell phones for half an hour a day for more than a decade |

-24 |

6 |

|

F1 |

Cell phone radiation has been shown to cause short term memory loss as well as Alzheimer’s |

-25 |

6 |

|

D4 |

Cell phone radiation is a suspected cause in neurological impairments in children including autism |

-14 |

3 |

|

F4 |

Cell phone radiation has been linked to breast cancer in women who carry their phones in their brassieres |

-23 |

3 |

|

F6 |

Over the past two years there’s been a 4-fold increase in malignant tumors of the parotid gland on the same side of the face that cell phone users hold their phone |

-24 |

2 |

|

D1 |

Cell phones emit radiation whenever they’re turned on |

-5 |

1 |

|

E1 |

The manual for every cell phone and smartphone sold in the world instructs users to NOT allow their phones to actually touch their ears! |

-13 |

1 |

|

F3 |

Cell phone radiation has been linked to sterility in males who keep their phones in their front pants pockets |

-21 |

1 |

|

E2 |

All cell phone manuals instruct users to NOT allow their phones to touch their heads! |

-11 |

0 |

|

E4 |

Believe it or not–cell phones have never been safety tested among children and teens |

-6 |

-1 |

|

E3 |

The tests showing cell phones to be safe are based on how people used cell phones 35 years ago–not the way you use them today! |

-3 |

-2 |

|

E5 |

Today you use your cell phones far more frequently than you did in the 1980’s when they were safety tested |

5 |

-4 |

|

C5 |

Cell phones give you the ability to reach anyone in an emergency |

2 |

-10 |

|

C7 |

Cell phones are so versatile that they have become indispensable |

6 |

-12 |

|

C3 |

Cell phones make it easy to work at home |

0 |

-13 |

|

B3 |

Cell phones give your family ability to reach you at any time |

-1 |

-15 |

|

C4 |

Cell phones make it easy to work outside the office |

3 |

-16 |

|

A3 |

Cell phones keep you in touch with your email wherever you go |

6 |

-17 |

|

A5 |

Cell phones let you stay in touch with your child(ren) at all times |

2 |

-18 |

|

A2 |

Cell phones let you stay connected to work |

4 |

-19 |

|

B1 |

Cell phones give you a personal sense of security |

4 |

-19 |

|

A4 |

Cell phones let you text each other whenever you want |

3 |

-19 |

|

A1 |

Cell phones let you stay in touch with your loved ones at all times |

2 |

-19 |

|

B5 |

Cell phones make it easier to pick up your kids from school and school events |

1 |

-19 |

|

B2 |

Cell phones let you to know where your kids are at all times |

-1 |

-19 |

|

B4 |

Cell phones give your kids the ability to reach you whenever they need you |

-1 |

-19 |

|

B6 |

Cell phones make travel easier |

-1 |

-19 |

|

C1 |

Cell phones make it easy to pick up people at the airport |

-5 |

-21 |

The ratings for each respondent were transformed to a binary scale, with ratings of 1–6 transformed to 0 to denote either not believable, or not bad, and ratings of 7–9 transformed to 100, to denote believable or bad. The transformations are based upon author HRM’s experience with the interpretation of the data. Users of the data, whether scientists, researchers, or managers, report no problem understand NO/YES data, but often experience and report problems with understanding exactly what does the scale ‘mean.’ SS Stevens, Professor of Psychophysics at Harvard University, often stated that ‘understanding the mean of the scales was often difficult …. the most important thing was to divide the scale so that the numbers could be understood without too much explanation’ [19] (Stevens, personal communication to HR Moskowitz, 1968.)

For each respondent, we run an OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression relating the presence/absence of the 36 elements (coded 0/1) to the binary responses (coded 0/100). Before the regression analysis was run, we added a very small random number to each binary response, whether coded 0 or 100, respectively. The small number was less than 10–5. The stratagem of adding a small positive random number ensures that the OLS regression would run, without any problem, but the size of the random number means that it had no virtually no effect on the results.

The OLS regression emerged with an additive constant, k0, and 36 coefficients, one coefficient corresponding to each element for each respondent. The experimental design enables the creation of individual-level models.

The additive constant shows the expected proportion of respondents who, in the absence of any elements in the vignette, would rate the vignette as ‘believable’ (question 1, rating 7–9) or ‘bad’ (question 2, rating 7–9.) The additive constant is a purely estimated parameter, estimated from the pattern of the ratings, but of course a parameter that could never be directly measured. The reason for the appellation of ‘theoretical’ or ‘purely estimated’ is that all vignettes comprised three-four elements, by virtue of the underlying experimental design.

Results

Mind Genomics generates a mass of data, interesting both in terms of the general patterns emerging, but also interesting by virtue of incorporating 36 messages, each of which conveys relevant information. We create an exceptionally large data set in these studies. We look at the mass of data, 36 messages, two response scales (believability, badness), and 304 respondents who can be placed into different subgroups, depending upon how they profile themselves. The analysis considers the highlights of these results.

Total Panel

We begin the analysis by looking at the summary data from out 304 respondents in Table 3. We average the corresponding coefficients from all respondents. The additive constant both for Question #1 (believe) and Question #2 (bad for you) are high, 59 for believable and 56 for bad. Thus, even before we add elements or answers to the vignette, our respondents are telling us that the base level is high for both believe and bad. The issue is whether any of the elements increase believability or increase the perception of bad.

The strongest elements increasing believability are those which are obvious, talking about either fact, or in the case of driving, the outcome of coordinated advertising over a decade or so. The elements increasing the perception of ‘bad’ are those which talk about issues, buttressed by numbers, presented either in numerical form (E6 -2000 hours; F2 – 5 times), or in text form but still numerical (D6 – exponential.)

What is remarkable about these results is the massive range of coefficients for believability, primarily in the negative direction.

The MOST BELIEVABLE elements are obvious, and part of the culture of ‘talking about cellphone.’ They do not talk about the medical issues involved.

- Cell phones let you reach anyone anytime you want

- Cell phones can be dangerous when driving

The LEAST BELIEVABLE elements talk about what is presented as scientific fact, some with numbers to quantify the assertion.

- A comprehensive study in Sweden indicates that children and teens are 5 times more likely to get brain cancer if they use cell phones

- Cell phone radiation has been shown to cause short term memory loss as well as Alzheimer’s

- People have twice the risk of developing the cancer known as “Glioma”, if they use their cell phones for half an hour a day for more than a decade

- Over the past two years there’s been a 4-fold increase in malignant tumors of the parotid gland on the same side of the face that cell phone users hold their phone

- Cell phone radiation has been linked to breast cancer in women who carry their phones in their brassieres

- Cell phone radiation has been linked to sterility in males who keep their phones in their front pants pockets

The LEAST BAD elements were the obvious ones, namely statements about the cell phone helps daily living.

The MOST BAD elements were those about the implication of the cell phone in causing disease, elements that at the same time were considered least believable. A comprehensive study in Sweden indicates that children and teens are 5 times more likely to get brain cancer if they use cell phones

- Brain cancer is directly linked to the exponential increases in cell phone use and other wireless devices

- People using cell phones for 2000 hours have 240% greater risk for malignant brain tumors

Respondents clearly differentiate between believability and the badness of the effect.

Gender differences

There are differences between males and females. Table 4 compares the coefficients for the genders.

Table 4. Gender. How the strongest performing elements drive believability (Q#1) and bad (Q#2)

|

Male |

Fem |

||

|

Base size |

159 |

145 |

|

|

Additive constant – Believable |

58 |

59 |

|

|

D3 |

Cell phones are so light and portable so you can take them anywhere |

12 |

6 |

|

D2 |

Cell phones can be dangerous when driving |

10 |

14 |

|

C6 |

Cell phones allow you to be reached by friends or family in an emergency |

10 |

5 |

|

C2 |

Cell phones let you reach anyone anytime you want |

9 |

12 |

|

A2 |

Cell phones let you stay connected to work |

1 |

8 |

|

Additive constant – Bad |

57 |

55 |

|

|

E6 |

People using cell phones for 2000 hours have 240% greater risk for malignant brain tumors |

11 |

4 |

|

D6 |

Brain cancer is directly linked to the exponential increases in cell phone use and other wireless devices |

10 |

5 |

|

F1 |

Cell phone radiation has been shown to cause short term memory loss as well as Alzheimer’s |

8 |

3 |

|

F2 |

A comprehensive study in Sweden indicates that children and teens are 5 times more likely to get brain cancer if they use cell phones |

5 |

8 |

|

D5 |

People with higher peak exposures to cell phone radiation have an 80 percent increase in the risk of miscarriage |

5 |

8 |

Table 5. Age. How the strongest performing elements drive believability (Q#1) and bad (Q#2)

|

Age 25–34 |

Age 45–54 |

||

|

Base Size |

142 |

33 |

|

|

Additive Constant – Believable |

50 |

77 |

|

|

D3 |

Cell phones are so light and portable so you can take them anywhere |

12 |

-2 |

|

C6 |

Cell phones allow you to be reached by friends or family in an emergency |

11 |

7 |

|

D2 |

Cell phones can be dangerous when driving |

11 |

5 |

|

C2 |

Cell phones let you reach anyone anytime you want |

10 |

15 |

|

A3 |

Cell phones keep you in touch with your email wherever you go |

10 |

8 |

|

A2 |

Cell phones let you stay connected to work |

3 |

9 |

|

B1 |

Cell phones give you a personal sense of security |

5 |

8 |

|

Additive Constant – Bad |

54 |

49 |

|

|

D6 |

Brain cancer is directly linked to the exponential increases in cell phone use and other wireless devices |

10 |

17 |

|

E6 |

People using cell phones for 2000 hours have 240% greater risk for malignant brain tumors |

9 |

3 |

|

F1 |

Cell phone radiation has been shown to cause short term memory loss as well as Alzheimer’s |

4 |

15 |

Table 6. Use Pattern. How the strongest performing elements drive believability (Q#1) and bad (Q#2)

|

Believe – Call versus Play for 1–2 hours |

Call |

Play |

|

|

Base |

43 |

64 |

|

|

Additive |

68 |

45 |

|

|

A2 |

Cell phones let you stay connected to work |

8 |

11 |

|

B5 |

Cell phones make it easier to pick up your kids from school and school events |

8 |

1 |

|

C2 |

Cell phones let you reach anyone anytime you want |

4 |

16 |

|

D2 |

Cell phones can be dangerous when driving |

7 |

13 |

|

E5 |

Today you use your cell phones far more frequently than you did in the 1980’s when they were safety tested |

7 |

13 |

|

D3 |

Cell phones are so light and portable so you can take them anywhere |

1 |

12 |

|

C6 |

Cell phones allow you to be reached by friends or family in an emergency |

1 |

11 |

|

A4 |

Cell phones let you text each other whenever you want |

1 |

10 |

|

A3 |

Cell phones keep you in touch with your email wherever you go |

5 |

9 |

|

A1 |

Cell phones let you stay in touch with your loved ones at all times |

1 |

8 |

|

Believe – Call versus Play for 1–2 hours |

Call |

Play |

|

|

Base |

43 |

64 |

|

|

Additive constant |

46 |

24 |

|

|

F1 |

Cell phone radiation has been shown to cause short term memory loss as well as Alzheimer’s |

12 |

16 |

|

D2 |

Cell phones can be dangerous when driving |

11 |

9 |

|

D4 |

Cell phone radiation is a suspected cause in neurological impairments in children including autism |

10 |

15 |

|

F2 |

A comprehensive study in Sweden indicates that children and teens are 5 times more likely to get brain cancer if they use cell phones |

9 |

21 |

|

E6 |

People using cell phones for 2000 hours have 240% greater risk for malignant brain tumors |

9 |

24 |

|

D6 |

Brain cancer is directly linked to the exponential increases in cell phone use and other wireless devices |

6 |

17 |

|

F6 |

Over the past two years there’s been a 4-fold increase in malignant tumors of the parotid gland on the same side of the face that cell phone users hold their phone |

6 |

16 |

|

F3 |

Cell phone radiation has been linked to sterility in males who keep their phones in their front pants pockets |

-1 |

13 |

|

D5 |

People with higher peak exposures to cell phone radiation have an 80 percent increase in the risk of miscarriage |

6 |

13 |

|

E1 |

The manual for every cell phone and smartphone sold in the world instructs users to NOT allow their phones to actually touch their ears! |

1 |

10 |

|

D1 |

Cell phones emit radiation whenever they’re turned on |

0 |

9 |

|

F5 |

People have twice the risk of developing the cancer known as “Glioma”, if they use their cell phones for half an hour a day for more than a decade |

7 |

9 |

|

F4 |

Cell phone radiation has been linked to breast cancer in women who carry their phones in their brassieres |

2 |

9 |

|

E3 |

The tests showing cell phones to be safe are based on how people used cell phones 35 years ago–not the way you use them today! |

1 |

8 |

|

E4 |

Believe it or not–cell phones have never been safety tested among children and teens |

7 |

8 |

Regarding BELIEVE

- Both show virtually the same additive constant for believable (58–59)

- Both believe the message about cell phones being dangerous while driving

- Males believe messages which communicate the functionality of the phone

- Females believe messages communicating about staying in touch

- However, the groups do not differ dramatically in what they perceived to be very believable. It’s a matter of degree

Regarding BAD

- Males respond more strongly in terms of ‘BAD’ for messages about the link between cell phones and brain cancer.

- Females respond more strongly in terms of ‘BAD’ for messages about miscarriages, and problems that children and teens may encounter.

Age Differences

We compare two different age groups, the larger younger group (ages 25–34) and the smaller older group (age 45–54). Neither of these groups is near retirement.

Regarding BELIEVE

- There are radical differences between the ages. The younger respondents are fundamentally more skeptical than the older respondents. The additive constant for the younger respondents is 50, the additive constant for the older respondents is 77. This is not due to base size, but rather to fundamental differences in the way that the groups respond to information.

- The younger respondents show greater differentiation in what they believe. We see this from the wide spread of the coefficients, wider for the younger respondents, narrower for the older respondents.

- Younger respondents believe strongly in statements about the general portability and usefulness of phones.

- Older respondents feel that the phone lets them ‘stay in touch’ with work

Regarding BAD

- The additive constants are approximately equal for the younger and the older respondents.

- Younger respondents feel that the messages about brain tumors are especially bad

- Older respondents feel that memory loss is bad, a more reasonable fear as a person gets older, because memory loss is common among older people.

Patterns of use – calling versus playing, 1–2 hours / week

Regarding BELIEVE

- Those who identify themselves as calling for 1–2 hours/week show a higher additive constant than those who identify themselves as playing for 1–2 hours/week. These are not mutually exclusive groups. We might conclude that those who use the cell phone for playing tend to ‘deny’ more, i.e., ‘believe’ less

- Those who use the cell phone for calling respond most strongly as the way to keep in contact.

- Those who use the cell phone for calling do not believe, quite as much, that cell phones can be dangerous when driving.

- Those who use the cell phone for play believe strongly in the phone letting them stay connected to work, and believe far more strongly that the cell phone simply lets them stay in touch.

Regarding BAD

- Those who use the cell phone for calling feel more strongly, at a base level, that the cell phone has bad aspects (additive constant = 46 for those who call, versus additive constant = 24 for those who play.)

- Both groups respond strongly to these five elements which are BAD

Cell phone radiation has been shown to cause short term memory loss as well as Alzheimer’s

Cell phones can be dangerous when driving

Cell phone radiation is a suspected cause in neurological impairments in children including autism

A comprehensive study in Sweden indicates that children and teens are 5 times more likely to get brain cancer if they use cell phones

People using cell phones for 2000 hours have 240% greater risk for malignant brain tumors

The two mind-sets based upon the coefficients for ‘believe’

One of the major underlying premises of this emerging science of Mind Genomics is that within any topic involving subjective judgment, people will differ from each other. We see such differences in the previous data tables, which clearly revealed that there are substantial differences in the messages that people believe, and the messages that they think are ‘bad.’ Inter-individuals appear to be random, however. There are some patterns, but often we have to ‘strain’ to discern the reason for the differences between mutually exhaustive, complementary groups, such as genders, the pattern of responses of males versus the pattern of responses versus females.

For Mind Genomics, the objective is to create a set of complementary, exhaustive groups, which show different patterns, these patterns in turn telling clearly different ‘stories.’ These groups are called Mind-Sets, or mental genomes. They are created through the class of statistical methods know as cluster analysis.

In simple terms, we follow these straightforward steps, to uncover the underlying Mind-Sets. The objective is to uncover a small number of such clusters or Mind-Sets, with the property that the pattern the coefficients ‘tell a story.’ The ideal is to end up with one mind-set, meaning everyone thinks alike, but that is almost unknown, except for one instance, an unpublished study by author HRM and colleagues on the response to ‘murder’ as a crime. The typical result is two or three mind-sets, few enough to be considered parsimonious. These mind-sets respond in ways that are clearly different, and which do seem to tell a simple story.

The steps to uncover the Mind-Sets follow this sequence:

- Create an individual model for each respondent relating the presence/absence of the 36 elements to the responses. In our case, the response is the binary transformation of Question #1, Believable, with ratings of 1–6 transformed to 0, and ratings of 7–9 transformed to 100. The underlying experimental design, used to create the 48 vignettes for each respondent, allow us to create the individual-level model, especially since we ensure that the OLS regression works by adding a very small random number to each transposed value, 0 or 100, respectively.

- Cluster the respondents using the pattern of their 36 coefficients for the first question, ‘BELIEVE.’ We could have just as easily clustered using the coefficients for the second question, ‘BAD.’ Clustering is a well-accepted statistical procedure, comprises a suite of different methods, all of which are really ‘heuristics,’ to uncover new patterns in the data. No one clustering method is ‘better’ than another in a mathematical sense. For this study, we used the method of k-means clustering.

- We extracted two clusters, really mind-sets, comprising two patterns. The patterns ‘make intuitive sense.’

Table 7 shows the strongest performing elements for the two Mind-Set segments, based on BELIEVE.

Table 7. Mind-Sets. How the strongest performing elements drive believability (Q#1)

|

Segmentation based upon responses to Question #1: Believe |

Mind-Set 1 |

Mind-Set 2 |

|

|

Base |

119 |

185 |

|

|

Additive constant |

68 |

53 |

|

|

Both mind-sets – believe that cell phones make like easier |

|||

|

C2 |

Cell phones let you reach anyone anytime you want |

12 |

10 |

|

Mind-Set 1 – Focus on work |

|||

|

C4 |

Cell phones make it easy to work outside the office |

8 |

0 |

|

Mind-Set 2 – Focus on security and safety |

|||

|

D2 |

Cell phones can be dangerous when driving |

4 |

17 |

|

E5 |

Today you use your cell phones far more frequently than you did in the 1980’s when they were safety tested |

-9 |

14 |

|

D3 |

Cell phones are so light and portable so you can take them anywhere |

5 |

12 |

|

B1 |

Cell phones give you a personal sense of security |

-5 |

10 |

|

A3 |

Cell phones keep you in touch with your email wherever you go |

1 |

10 |

|

C6 |

Cell phones allow you to be reached by friends or family in an emergency |

7 |

8 |

- The two mind-sets differ both in the additive constant and in the patterns of the strong performing elements.

- Both Mind-Sets believe strongly on one very obviously element, C2, Cell phones let you reach anyone anytime you want

- Mind-Set 1 focuses on work. Mind-Set 1 has a higher additive coefficient, 68, meaning that it responds to one element most strongly, C4, Cell phones make it easy to work outside the office.

- Mind-Set 2 focuses on security and safety. Mind-Set 2 begins with a slightly lower additive constant, 53, but responds strongly to six elements, the strongest being D2, Cell phones can be dangerous when driving. Surprisingly, for Mind-Set 1, this element, so well-drilled into people’s minds by the traffic authorities, is not particularly believable, with an additive constant of 4. The reason might be because Mind-Set 1 already believes a lot, with an additive constant of 68, so this is just another element on top of a basically high proclivity to believe.

- The strongest messaging to create awareness of risk among people in the Mind-Set 1 is that smartphones usage is directly linked to brain tumors. The strongest messaging to create awareness among people in Mind-Set 2 is that the use of smartphones increases the risk for brain tumors in children and teens by five times, that 2000 hours of exposure to smartphones increases the risk for malignant brain tumors by 240% , and the risk for miscarriage by 80 percent.

Discovering these Mind-Sets in the population

In the world of advertising, most advertisers buy advertising on the basis of WHO THE CUSTOMER IS. Marketers have come to the realization that it is not a question of WHO, but rather a question of WHAT the customer thinks. Unfortunately, for most research there is no easy, affordable, scalable allowing advertisers to know exactly the message which will resonate with the members of the audience.

In the world of commerce the failure to know the ‘hot buttons’ or persuasive messages resonating with an individual consumer is simply an endemic, well-accepted cost of doing business. Knowing that a person may or may note resonate to a particular message about a car, a toothbrush, a candy is simply a ‘given’, and not something which worries economists and those tasked with the welfare of a nation. On the other hand, when the issue comes to matters of health, and especially with widespread products such as smartphones, this lack of knowledge is problematic.

The answer to knowing the mind of a person can be operationally redefined as assigning a ‘new person’ as a member of a mind-set segment. This ability to assign a new person to a mind-set allows the health authorities and others with feelings of social responsibility to send the ‘right message to the right person.’ Sadly, however, membership in the mind-set is not a simple function of WHO A PERSON IS.

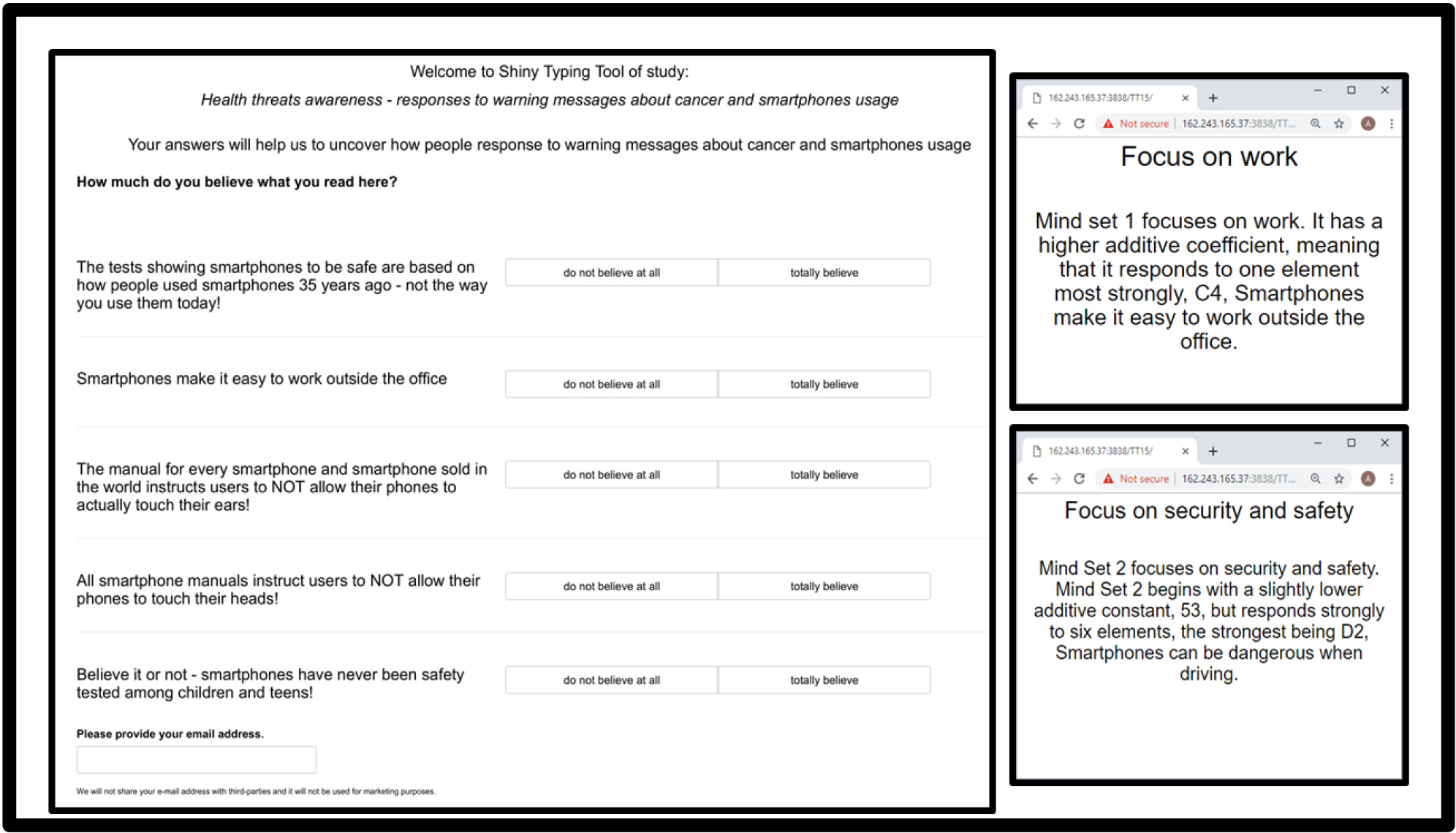

An alternative is the PVI, the personal viewpoint identifier. The experiment presented in this study provides the necessary messages to differentiate the two mind-sets. What is necessary is a set of questions, emerging from the study, which best differentiate people in the mind-sets. That is, the ideal is to provide a person with a set of, say, six questions, as shown in Figure 1. These are the questions which best differentiate between the segments. The pattern of responses to the six questions on the 2-point scale assigns the new person to one of the two mind-sets. Figure 1 shows the actual questionnaire, and an example of the feedback. The respondent completes the PVI, provides an email, and the information returns, either to the respondent who is being typed, and/or to the group doing the messaging. The PVI is set up to request additional information, so one can use the PVI to understand the distribution of the mind-sets in the populations.

Figure 1. The PVI (personal viewpoint identifier) to assign a new person to one of the two specific mind-sets uncovered in this study. The web link as of this writing (2019) is http: //162.243.165.37: 3838/TT15/

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study we identified communication messaging aimed at creating awareness to health risks in usage of smartphones. We revealed two mind-set segments and illustrated how to use our viewpoint identifier tool to easily learn the belonging of a person in the population to one of the mind-set segments.

All respondents believed the use of smartphones is essential for communication. People belonging to the first mind-set segment believe smartphones should serve only for work purposes. The strongest message regarding risk was that smartphones usage is directly linked to brain tumors. People belonging to the second mind-set segment perceive smartphones as dangerous when driving but increase one’s sense of security outside of driving. Strong messages regarding risks of smartphone usage are that it holds a five times greater risk of brain cancer for children and teens; it exposed the user to a 240 percent higher risk for malignant brain tumors upon usage of 2000 hours; and for females higher peak exposures to smartphone radiation, will increase the risk of miscarriage by 80 percent.

The epidemic of cancer and rising expenditures of healthcare by governments and individuals calls for the use of insights of our study, and to extend this study to other aspects involved in the wide-use of smartphones. Messages on risks of smartphone usage may be adopted by social movements which promote a “no cellphone day” campaigns, encouraging people to detach from their smartphones for a certain time period. Health prevention programs may also integrate this messaging with their additional efforts. The Mind Genomics efforts are quick, iterative, knowledge-producing, and scalable, as well as providing follow-on application using the PVI.

Acknowledgement

Attila Gere thanks the support of the Premium Postdoctoral Research Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

References

- Ali AI, Papakie MR, McDevitt T (2012) Dealing with the distractions of cell phone misuse/use in the classroom-a case example. In Competition Forum. American Society for Competitiveness 1: 220.

- Dubey RB, Hanmandlu M, Gupta SK (2010) Risk of brain tumors from wireless phone use. J Comput Assist Tomogr 34: 799–807. [crossref]

- Hours M, Bernard M, Montestrucq L, Arslan M, Bergeret A, et al. (2007) Smartphones and Risk of brain and acoustic nerve tumours: the French INTERPHONE case-control study. Revue d’Epidemiologie et de Sante Publique 55: 321–332.

- Obringer SJ, Coffey K (2007) Cell phones in American high schools: A national survey. Journal of Technology Studies 33: 41–47.

- Horrey WJ, Wickens CD (2006) Examining the impact of cell phone conversations on driving using meta-analytic techniques. Human Factors 48: 196–205.

- Repacholi MH (2001) Health risks from the use of mobile phones. Toxicol Lett 120: 323–331. [crossref]

- Gustafsson E, Thomée S, Grimby-Ekman A, Hagberg M (2017) Texting on mobile phones and musculoskeletal disorders in young adults: a five-year cohort study. Applied Ergonomics 58: 208–214.

- Volkow ND, Tomasi D, Wang GJ, Vaska, P, Fowler JS, et al. (2011) Effects of smartphone radiofrequency signal exposure on brain glucose metabolism. Journal of the American Medical Association 305: 808–813.

- Wolf R, Wolf D (2004) Increased incidence of cancer near a cell-phone transmitter station. International Journal of Cancer 1: 123–128.

- Hardell L, Sage C (2008) Biological effects from electromagnetic field exposure and public exposure standards. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 62: 104–109.

- Jenaro C, Flores N, Gómez-Vela M, González-Gil F, Caballo C (2007) Problematic internet and cell-phone use: Psychological, behavioral, and health correlates. Addiction Research & Theory 15: 309–320.

- Thomée S, Härenstam A, Hagberg M (2011) Mobile phone use and stress, sleep disturbances, and symptoms of depression among young adults-a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 11: 66.

- Brown JD, Bobkowski PS (2011) Older and newer media: Patterns of use and effects on adolescents’ health and well-being. Journal of Research on Adolescence 21: 95–113.

- Khurana VG, Teo C, Kundi M, Hardell L, Carlberg M (2009) Cell phones and brain tumors: a review including the long-term epidemiologic data. Surg Neurol 72: 205–214. [crossref]

- Shakir IA, Patel NH, Chamberland RR, Kaar SG (2015) Investigation of smartphones as a potential source of bacterial contamination in the operating room. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 97: 225–231.

- Grazioli S, Carrell R (2002) Exploding phones and dangerous bananas: perceived precision and believability of deceptive messages found on the internet. AMCIS 2002 Proceedings, 271.

- Zarefsky D, Bizzarri N, Rodriguez S (2005) Argumentation: The study of effective reasoning. Teaching Company.

- Gofman A, Moskowitz H (2010) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127–145.

- Stevens TH, Barrett C, Willis CE (1997) Conjoint analysis of groundwater protection programs. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review 26: 229–236.