Abstract

Some years back, the authors were introduced to the International Franchise Association (IFA). The issue was raised as to how the emerging science of Mind Genomics might help the IFA to better understand the mind of the person contemplating involvement with a franchise. In response, we did a study to investigate the drawing power to franchises of elements. Our target population comprised people who were not currently franchisees, but who might be with the right messages. Mind Genomics deconstructed the current messages of franchises, and then recombined these by experimental design, tested among these non-franchisee prospects, only to reveal that many of the commercially uses messages do not motivate. Mind Genomics revealed that the appeal of franchise ideas could not be optimized for the total population as a single cohort, but only for the different mind-set segments ready to accept certain types of messages. The first mind-set could be characterized as You won’t have to go it alone respond to messages with this theme. The second mind-set segment could be characterized as You’ll be secure responds most strongly to one message that promises that. The third mind-set segment t responds to messages with the theme: You can run your business better. This group comprises a quarter of the respondents and constitutes the target group for franchising.

Introduction

Have you ever been at a franchise like Dunkin Donuts, a Mavis Tires or the Tru Value Hardware store? Chances are that you have, and either eaten there or bought something or had something repaired. The likelihood is that one of these stores is just like any another, but that the proprietor, if you were lucky enough to meet him, was a proud owner of this commercial enterprise which looked like hundreds, perhaps thousands of its fellow stores.

A franchise is a business which uses a parent company’s name to sell a product while maintaining a degree of independence from the parent. The parent company is called the franchisor, and the person opening one of these satellite firms is the franchisee. They latter buys the franchise, the right to use the name, the right to sell the products offered to the franchisees as long as they fulfill certain requirements, like buying their raw materials or decorate the store in a specific way, and so forth [1].

The ultimate decision whether to franchise a product or service concept rests with the franchisor. Resarch into the motivation underlying the creation of a franchise relationship has focused almost entirely on the franchisor. An impressive amount of theoretical and empirical economic research has been conducted to explain why firms choose to distribute their products or service offerings through franchise channels [2].

The reasons why individuals join franchise systems and the characteristics that predict which individuals are likely to be interested in becoming franchisees have received little attention [2–4]. In the economic literature, the decision of the franchisee to purchase a franchise has been assumed to be a rational response to an attractive investment opportunity [2].

Researchers have sought the most important perceived advantage(s) of franchising among various groups. For example, in one study British franchisees identified national affiliation (affiliation with a nationally known trademark) as the most important [5]. Knight [6] found known trade name to be most important to a group of Canadian franchisees. We all know that franchisors spend freely on national advertising and marketing for their product line. The purpose of this advertising is to promote sales for the entire franchise chain, and the franchisee benefits from this publicity. Withane [7] found proven business format to be the most important feature to another sample of Canadian franchisees. In a study of U.S. franchisees, Peterson & Dant [3] found that people with no self-employment history ranked training as very important. Franchisors offer technical assistance to franchisees. This type of assistance includes the training of a franchisee in effective management techniques, linking the franchisee with suppliers of materials or resources that are needed in production, and so on. Another important factor was greater independence [3]. Many prospective franchisees are driven by frustration in jobs where they didn’t have enough control to influence results in the way they wanted. Maybe they had a micro-managing boss, a parent corporation that wouldn’t listen, or something similar. Whatever the details, they’re drawn to the idea of being their own boss, having the last say in business decisions and knowing – for better or worse – that they’re responsible.

A key business benefit is that franchises are fairly easy to organize. Like other businesses, the franchisee must abide by local zoning rules. The franchisee’s creditworthiness typically gets a boost from being associated with a major franchise chain such as McDonald’s, Radio Shack, or H&R Block. The franchisor may even help finance the start-up costs for your business. This is important because the range of start-up costs runs from thousands of dollars to hundreds of thousands of dollars [8].

To summarize, franchising is a popular way to start an entrepreneurial business. Franchising is a wonderful way to run a business, offering the freedom and control running one’s own establishment, while at the same time capitalizing on demand created because the business has been in existence many years, and has a loyal following.

Origin of the Mind Genomics Study on the Mind of a Person Thinking about Franchising

The authors were introduced to the International Franchise Association (IFA), headquartered in a meeting in Washington, D.C. Through discussions the issue was raised as to how might Mind Genomics help the IFA better understand the mind of the person thinking about franchising. One could go to the website to learn about franchising, but it wasn’t clear what elements were ‘hot buttons’ to prospects. And so, this study was run, as part of the outcome of that discussion.

Exploring the full world of franchising in one study is an impossible task. There are thousands of franchises of different types just in the United States alone. We decided to study factors that would interest people who aren’t necessarily franchisees at the moment but might be interested. We had no idea about what the ‘hot buttons’ would be.

We began the study by developing the elements. Some of the elements appear in Table 1. The task of developing elements in a new topic area can be made very easy by ‘research.’ Research in this case consists of going to different websites that deal with franchising and specific franchises, downloading the text, and abstracting key phrases [9].

Table 1. Some of the elements from the franchise study.

|

Silo A – Support to the franchisee |

|

Up to date operations manuals are provided to all franchisees |

|

Silo B – Problems (business, social, individual) that the franchise helps to solve |

|

80% of independent businesses fail over 5 yrs – only 5% of franchisees fail over same period |

|

Silo C: Financial benefits of owning a franchise |

|

Delivers consistent brand promise and customer service |

|

Silo D: Managing the different financial aspects of the operation |

|

Effective system to deal with brand management |

|

Silo E: The type of business |

|

A great idea if you want to open a product-based business |

|

Silo F: Positives about franchise employees |

|

Franchise employees tend to manage costs better than company employees |

|

Silo G: Additional benefits from franchising |

|

Franchisees help drive the major innovations – not always from HQ |

The research effort was productive. In fact, going through more than a dozen websites we ended up with 128 different elements or simple phrases. The real question then is how to deal with this richness. We discovered different topics, some topics more diffuse and going in many directions, others quite focused with elements that could be easily substituted for each other.

For the franchise study, we sorted the elements into silos. There are no standard rules which dictate what the silos should be. That decision is left to the investigator. The only requirement is that the structure of the element follows one of the pre-designed templates. The template ensures that each silo comprises a limited number of elements, and that each silo comprises the same number of elements. In this study we developed seven silos with five elements each.

How the Mind Genomics Experiment Proceeds on the Internet

The research ‘protocol’ or steps in the experiment is straightforward when one does Mind Genomics experiments on the Internet. Only the venue changes, from an interview on a computer in a central location to a computer in the privacy of one’s home, used when it is convenient. The respondent receives an e-mail invitation. The respondent ‘clicks’ on the embedded link in the invitation and is taken to the Mind Genomics interview.

We see the introductory screen in Figure 1. There is nothing special about this screen. It simply tells the respondents what the study is about (i.e., franchise programs), a bit about the topic, and then the rating question. Very little is said about the topic, other than a general introduction. The objective is to set the scene, with the elements themselves driving the response.

Figure 1. The orientation page.

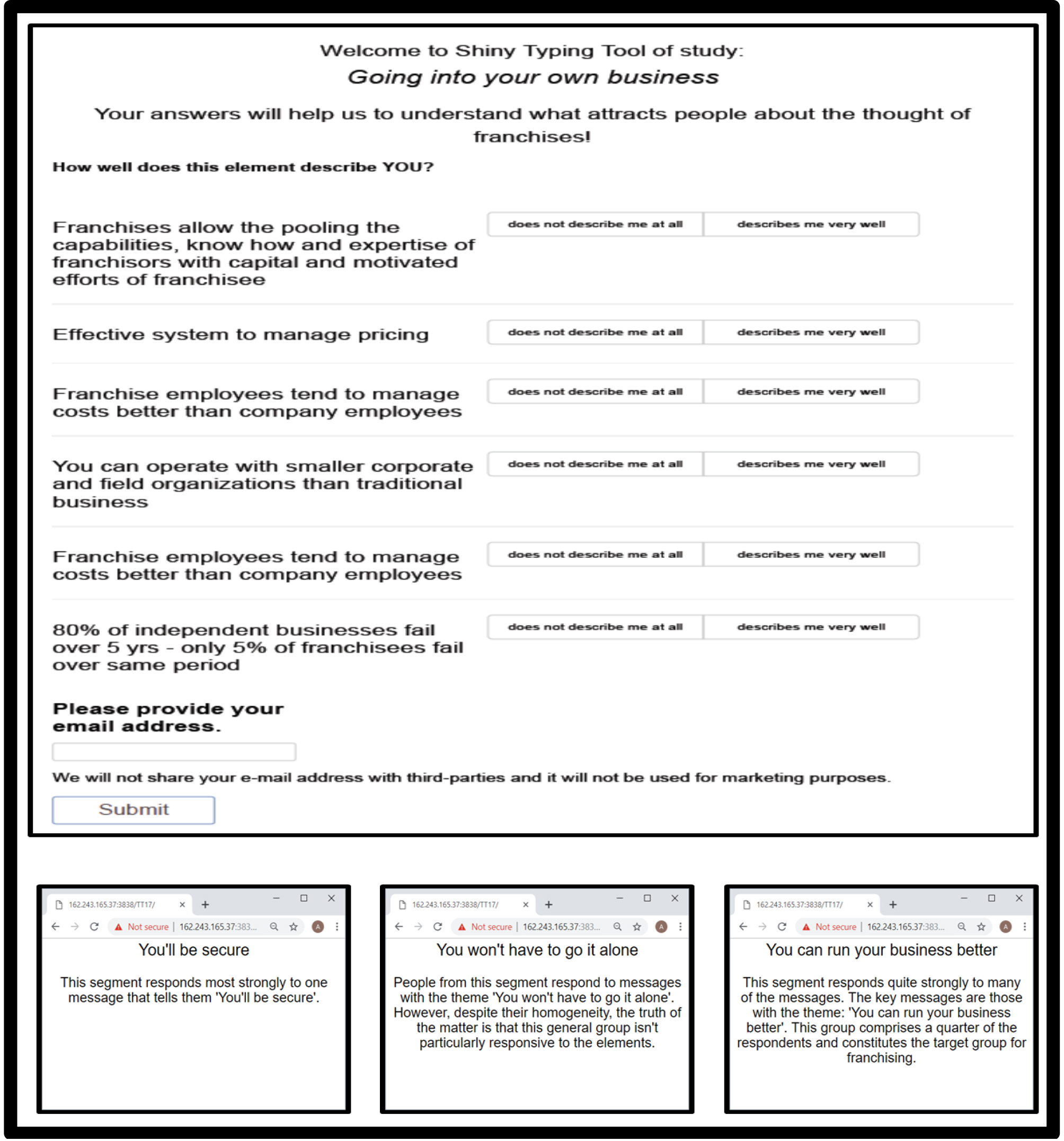

The interview continues with the different test vignettes, an example of which appears in Figure 2. The Mind Genomics experiment is straightforward. It mixes and matches the elements to create small, easy to read combinations of elements, the franchise vignettes. Mind Genomics creates different vignettes for each respondent. Each respondent rates 63 unique combinations. Elements in the combinations appeared independently of each other, as free agents, directed by an underlying experimental design. The design ensured that each element appeared equally often, and that only one element or no elements from a silo appeared in the test vignette. The size of the vignettes varied from 2–4 elements, so that no vignette could be considered complete. In the language of research design the vignette is a so-called ‘partial profile.’

Figure 2. The PVI, personal viewpoint identifier and three feedback screens, one for each mind set to which a person might be assigned.

These types of vignettes are easy to read. The elements are placed one atop the other, in centered format, without any connectives. The respondents can quickly examine the vignette and react. Such formats for Mind Genomics allow the respondent to evaluate many dozens of vignettes without becoming fatigued. There is no need to ‘search through’ the vignette to find the relevant information.

Each respondent evaluated a unique set of 63 vignettes. The underlying experimental design was maintained throughout, but the specific combinations varied from respondent to respondent [10]. It was strategically more effectively to sample more combinations with less precision than just a few combinations with greater precision. The latter, fewer stimuli but greater precision, typifies the current thinking about research, but has the implicit requirement that these few combinations truly represent the underlying space of alternatives. In contrast, Mind Genomics assumes no knowledge, and covers a wide spectrum of different combinations, in what might be metaphorically called an ‘MRI of one’s thoughts about a topic.’

Converting the Ratings from a 9-Point Scale to a Binary Scale

Consumer researchers are the ‘intellectual children’ of sociologists. They’re not the real children of course, but the thinking of a consumer researcher comes from sociology. Sociology focuses on people in groups, not on the microcosm of a person’s head. So, when a sociologist or consumer researcher looks at the 9-point scale, the real question is whether a person is interested or not interested. That is, to what group does the respondent belong? The notion of ‘belonging’ does not have to apply to the respondent as a person, but rather can apply to the particular response to a question. Continuing along that line of thought, when a respondent rates a vignette 1–6, we say that the respondent belongs to the group who is not interested that vignette. When the respondent rates a vignette 7–9, we say that the respondent belongs to the group who is interested that vignette. We also add a very small random number (<10–5) to the transformed number, the 0 or 100, respectively. The small random number ensures that there is at least a little bit of variation in the binary transformed number, even when the respondent confines his or her ratings either to the low end of the scale (1–6) or to the high end of the scale (7–9). With the addition of the small random there is guaranteed variation in dependent variable, and the analysis will run, without problems.

Now that we have moved to a binary system, ratings of 1–6 are to be considered as ‘not interested,’ and so we will re-code as 0 and ratings of 7–9 are to be considered as ‘interested,’ and we will re-coded as 100, we can do our analysis, using OLS (Ordinary Least-Squares) regression. The independent variables are the 35 elements for franchising. They take on the value 0 when they are absent from a vignette, and the value 1 when they are present in a vignette.

Creating the Models Relating the Franchising Elements to the Responses

Experimental designs are important in Mind Genomics. Because of the systematic arrangement we can develop a descriptive model. The model, an equation, shows how many rating points is contributed by each element, in the opinion of each respondent. We deduce the contribution of each element by looking at the pattern of responses, and how that pattern co-varies with the different elements in the shown vignettes. It can be readily analyzed by the statistical method of ordinary least squares [11]. OLS is one of a class of methods called curve-fitting. OLS finds the relation between the ‘independent variables’ – the appearance of an element within a vignette – and the dependent variable, the 9-point rating.

OLS uses statistical procedures to create an equation of the form:

Concept Rating = k0 + k1(Element A1) + k2(Element A2) … k35(Element G5)

The foregoing equation summarizes the relation between the variables, A1 – G5, and the rating. Each element either appears in a vignette, in which case the element is coded ‘1’, or the element does not appear in a vignette, in which the element is coded ‘0’. This is called ‘dummy coding.’ The term is based upon the fact that the independent variable is either absent (0) or present (1). The rating is the 9-point rating, assigned by the respondent.

Each respondent generates 35 coefficients, one for each tested element as well as an additive constant. The additive constant is defined as the expected score in the absence of any elements. Obviously, no one simply rated franchising without something to rate. However, when we do curve fitting, as OLS does, we use a linear equation of the form Y = mx + B. Our additive constant is B. The additive constant is a purely estimated parameter.

Let’s now look at the results of the modeling. We create the model for each one of our 102 respondents. Recall that each respondent evaluated a totally unique set of combinations, albeit created with the same 35 elements. When we run the OLS regression to create the model, we do this regression 102 times. Modern statistical programs can estimate the additive constant and the 35 coefficients in a matter of seconds. The average additive constant and coefficients for the 35 elements appear in Table 3. We created the 102 Interest Models, and simply averaged the corresponding parameters across the 102 respondents.

We begin with the additive constant. The additive constant tells us the conditional probability (in %) of respondents who would have rated the vignette 7–9 in the absence of any elements. The constant is 22. By design, all vignettes comprised 3–4 elements, so the additive constant is an estimated parameter. Yet the additive constant has informational value. It is a baseline, telling us the basic interest or predilection to be interested in franchising. It’s not high, only one person in five. That means, the elements must do most of the work to convince, at least for the total panel. We’ll see other results in a moment that are more promising, but just starting with total panel tells us we have to get the right messaging, or we have what’s colloquially called a ‘non-starter.’

We sorted the elements from highest to lowest. That stratagem allows us to discover the range of coefficient values, and in turn whether or not we have any coefficient values which really stand out. Statistical analysis as well as observations from many thousands of these Mind Genomics studies suggest that we’re likely to see significant and meaningful effects when the coefficient value for an element is +10 or higher or -5 or lower.

The most important thing to strike our note in Table 2 is the very narrow range of coefficient values. The highest coefficients are +4, and are quite discouraging. Nothing seems to excite respondents. The elements come from different silos, and do not show any consistent patterns. The lowest coefficients are -3

Table 2. Coefficients for the 35 elements from the franchise study. The numbers come from the total panel, and from the Interest Model. The elements are sorted from highest coefficient to lowest coefficient.

|

Mind Genomics study on responses to franchise definitions and benefits |

Total Sample |

|

|

Base size |

102 |

|

|

Additive constant |

22 |

|

|

A1 |

Up to date operations manuals are provided to all franchisees |

4 |

|

A3 |

Franchises receive store design courses to create the optimal settings |

4 |

|

A4 |

Continuing systems support -available at all times |

4 |

|

C3 |

A franchise creates successful distributions systems with benefits to business and customers |

4 |

|

C5 |

Allows people to open more locations quickly with less capital |

4 |

|

E4 |

A great idea if you want to open a home-based business |

4 |

|

G4 |

You can operate with smaller corporate and field organizations than traditional business |

4 |

|

G5 |

When you are a franchisee you are backed by a stabilizing force |

4 |

|

A2 |

You will receive helpful site selection support to maximize visibility |

3 |

|

A5 |

Franchises are automatically part of a network of other franchisees… share tips to succeed |

3 |

|

B1 |

80% of independent businesses fail over 5 yrs – only 5% of franchisees fail over same period |

3 |

|

B2 |

Franchisors help franchisees minimize mistakes based on their development and learning of that franchise |

3 |

|

B3 |

A franchise has enforceable standards to protect franchise system and brand |

3 |

|

C1 |

Delivers consistent brand promise and customer service |

3 |

|

C2 |

You will get high returns on your invested capital |

3 |

|

G2 |

You can experience rapid market penetration |

3 |

|

B4 |

A franchise helps transfer business technology to emerging markets |

2 |

|

C4 |

A franchise gives you the ability to replicate your franchise in other locations inexpensively |

2 |

|

E1 |

A great idea if you want to open a product-based business |

2 |

|

E2 |

A great idea if you want to open a service driven business |

2 |

|

F1 |

Franchise employees tend to manage costs better than company employees |

2 |

|

D2 |

Effective system to manage pricing |

1 |

|

E5 |

A great idea if you want to open a mail-based business |

1 |

|

G1 |

Franchisees help drive the major innovations – not always from HQ |

1 |

|

D3 |

Effective system to manage national accounts |

0 |

|

D5 |

Effective system to manage IT systems, such as point of sale innovations, accounting, centralized billing and collections |

0 |

|

F2 |

Franchise employees tend to reduce spoilage and shrinkage |

0 |

|

F4 |

Franchise employees are usually better focused when making hiring decisions |

0 |

|

F5 |

Franchise employees are usually better at controlling wages and benefits |

0 |

|

G3 |

Franchises allow the pooling the capabilities, know-how and expertise of franchisors with capital and motivated efforts of franchisee |

0 |

|

E3 |

A great idea if you want to open a hi-tech business |

-1 |

|

F3 |

Franchise employees tend to manage labor costs better |

-1 |

|

B5 |

Can be used to solve critical issues like malaria, clean water etc. |

-2 |

|

D1 |

Effective system to deal with brand management |

-2 |

|

D4 |

Effective system to manage inventory purchasing |

-3 |

Table 3. Coefficient values for strongest and weakest elements from the franchise study. The numbers from the three mind-set segments

|

Mind-Set |

|||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

|

Base size |

55 |

22 |

25 |

|

Additive constant |

21 |

26 |

22 |

|

Mind-Set 1 – You won’t have to go it alone |

|||

|

Up to date operations manuals are provided to all franchisees |

8 |

-4 |

4 |

|

Allows people to open more locations quickly with less capital |

7 |

-5 |

5 |

|

Franchises receive store design courses to create the optimal settings |

7 |

-4 |

3 |

|

Continuing systems support -available at all times |

7 |

0 |

3 |

|

Can be used to solve critical issues like malaria, clean water etc. |

-6 |

6 |

1 |

|

Mind-Set2 – You’ll be secure |

|||

|

80% of independent businesses fail over 5 yrs – only 5% of franchisees fail over same period |

-4 |

13 |

11 |

|

Delivers consistent brand promise and customer service |

6 |

-7 |

5 |

|

Franchise employees tend to manage costs better than company employees |

3 |

-7 |

7 |

|

Mind-Set 3 – You can run your business better |

|||

|

You can operate with smaller corporate and field organizations than traditional business |

-2 |

4 |

15 |

|

Effective system to manage pricing |

-4 |

-4 |

14 |

|

When you are a franchisee you are backed by a stabilizing force |

0 |

3 |

12 |

|

80% of independent businesses fail over 5 yrs – only 5% of franchisees fail over same period |

-4 |

13 |

11 |

|

Franchises allow the pooling the capabilities, know how and expertise of franchisors with capital and motivated efforts of franchisee |

-4 |

-3 |

10 |

|

You can experience rapid market penetration |

1 |

2 |

9 |

|

A franchise helps transfer business technology to emerging markets |

-1 |

-1 |

9 |

|

Franchisors help franchisees minimize mistakes based on their development and learning of that franchise |

-1 |

6 |

8 |

|

A franchise creates successful distributions systems with benefits to business and customers |

6 |

-4 |

8 |

|

A great idea if you want to open a hi-tech business |

1 |

-2 |

-4 |

What do we conclude from these coefficients? They certainly are low, both in basic interest and in the drawing power of the individual elements. On reflecting about the results, we should not be particularly surprised. We are talking here to a general population, not to individuals who are ready to buy into a franchise. Perhaps, then, the answer lies in subgroups, which it does, as we will see in the next section.

Three Mind-Sets Regarding Franchising

Mind-set segmentation has proven to be a very strong outcome in the world of Mind Genomics, and continues to do so, as we will see from these data. We cluster the 102 respondents on the basis of their individual coefficients [12]. Through our experiments using Mind Genomics we find that segmentation reveals groups of related elements which score strongly among a specific group of people.

Whereas most segmentation divides people and then hopes to find ideas moving in tandem with that division, we are doing the exact opposite. We identify the ideas, find the different basic groups of ideas, and then assign a respond to a group based on his behavior specific to the topic.

Although we went into the franchise study not knowing much except what was presented at the website, the respondents appear to know more than we might believe. We say this because our initial foray into the results suggested that nothing worked, nothing ‘popped,’ and that the entire exercise could be classified as simply one big yawn. And we would be correct. We could ascribe it to the fact that we didn’t have the correct elements, or that we didn’t poll the correct respondents, or that we didn’t ask the correct questions.

Now let’s look at what happens when we have an almost self-organizing system, without our conscious intervention, and without any knowledge ahead of time. Our inputs comprise the stimuli, the raw material from the websites on franchising, and respondents, the minds of regular, ordinary, run-of-the-mill respondents who may or may not be interested in franchising. What happens when we cluster these people, dividing them into groups with similar patterns of coefficients?

We end up with three segments. The clustering is a simple, almost mechanical procedure, searching for patterns in data. The patterns must be statistically valid, which is ensured by the clustering algorithm (k-means.) The clustering must be conceptually valid, meaning that the clusters or mind-sets emerging from the clustering effort must make sense in two ways:

- The clusters must be parsimonious. Fewer clusters or mind-sets are better than many clusters.

- The clusters must ‘tell a story’. The strongest performing elements in each cluster must combine in a way to send a harmonious message, rather than ‘fighting with each other and going in different directions.’ This coherence is subjective, left to the researcher.

Table 3 shows the highlights from the clustering, which emerged with three segments or mind-sets about franchising. All three mind-sets segments begin with low additive constants, meaning that the respondents in the mind-set are not fundamentally interested in franchising. It will be the elements which do the work to convince. The mind-sets suggest to us that there will be three patterns of elements which convince, and that a person will be more likely to be convinced by one of the three patterns, and less likely to be convinced by the other two patterns.

- Mind-Set 1: People from this segment respond to messages with the theme You won’t have to go it alone. However, despite their homogeneity, the truth of the matter is that this general group isn’t particularly responsive to the elements.

- Mind-Set 2: This segment responds most strongly to one message that tells them You’ll be secure.

- Mind-Set 3: Although they begin with a low additive constant (22), they respond quite strongly to many of the messages. The key messages are those with the theme: You can run your business better. This group comprises a quarter of the respondents and constitutes the target group for franchising.

It is clear, therefore, that the big opportunity for franchising is both identifying the key messaging, and then sending those messages to the correct person. By segmenting the respondents according to the type of message to which they respond, we see that we can take what might otherwise be a bland set of messages from a website, and both discover ‘what works, and with whom.’

We are missing only one thing; how do we find these segments in the population. And strategies for finding them will be our next and last section in this chapter.

Finding the Segments in the Population

When we look at the segmentation results from Table 3, we should be struck by the fact that there is really only one group of respondents who comprise our target. These individuals are the respondents in Mind-Set 3. Ordinarily we might look for individuals who fall into this mind-set. That makes a great deal of sense. Mind-Sets 1 and 2 do not comprise people who respond particularly strongly to ideas about franchising. Indeed, the truth of the matter is that the basic idea of franchising is not appealing, with a low additive constant (25 or less). It’s the elements which must do the ‘heavy lifting’ to convince, and the elements only work among Segment 3.

In order to type a person, we apply an approach used by today’s doctors. Rather than relying on family history, still a valuable source of information, we can use short interventions. Physicians do this all the time. The beginning of most medical exams comprises a blood test, or an electrocardiogram, and so forth. These are interventions, small tests that interact with the respondent, measure a response, and then compare that response to a set of norms and diagnostics.

Recently, author Gere has developed an algorithm to assign a new person to one of the mind-sets. The approach has been used to assign new people to a mind set in a variety of different applications, ranging from medicine to food. The approach has been made deliberately simple to make it applicable with data collected in previous studies.

The sequence below describes the process, first for two mind sets, and then noting how to extend the approach to three minds.

- First, we subtract the two vectors (element by element) and compute their absolute difference (e.g. abs(x-y))

- Then look for the five highest differences e.g. we look for the elements that are the farther from each other in terms of the response of the two mind sets.

- Open up a new worksheet, and list all the elements and their absolute difference

- Each chosen element (the five in step 2) receives one vote.

- Add random noise to the two vectors of elements and repeat steps 1–4.

- Repeat steps 1–4 a total of 1,000 times. This is called a Monte Carlo simulation with bootstrapping

- At the we look at the table created in step 4 and chose those five elements which were chosen as most discriminating the most times.

- In the case of three segments we do the same but in the first step we create three additional variables (S1-S2, S1-S3 and S2-S3) instead of one variable (S1-S2) and choose 6 elements not five.

- Steps 1–8 produce the necessary information to create a basic PVI, personal viewpoint identifier, which uses the five or six elements, in the form of questions, and assigns a new person to one of the two (or three) mind sets.

- Create an interface which accepts the input data from a new person, and returns with the assignment, as well as storing other information about the respondent. For this project, the PVI is, of this writing (March, 2019), located at: http://162.243.165.37:3838/TT17/

Figure 2 shows an example of the PVI for this study, and the three feedback screens which emerge after a new person is assigned to one of the three mind-sets. The screens can be adjusted to accord with he the requirements of the project, may be sent to the candidate doing the typing, or to an interviewer who is ‘vetting’ the candidate for a franchise, or even attached to a person’s data record for further use by other parties interested in working with the candidate.

Summing Up

Franchising is growing our economy because it provides certain benefits of a big company, while at the same time letting a person be his own ‘boss.’ Yet, as our Mind Genomics exercise shows, the messages that are offered on commercial franchise websites are not particularly motivating.

Our exercise suggested that a great deal motivation might emerge from segmenting the respondents in terms of their mindsets. The Mind Genomics exercise suggests at least three mind-set segments, although there might be more. Two mind-set segments did not suffice. The problem, however, is to identify the mind-set segment to which a person belongs.

We introduced the notion of an intervention by mind-typing. The respondent rates a set of elements, namely those coming from the original Mind Genomics exercise, and then using the ratings, assign the person to the appropriate mind-set segment. The results of the exercise are likely to provide better fits of people and franchises, as well as providing a new avenue for the application of Mind Genomics to the issues dealt with in applied psychology.

Acknowledgement

Attila Gere thanks the support of the Premium Postdoctoral Research Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Reference

- Lafontaine F, Kaufmann PJ (1994) The evolution of ownership patterns in franchise systems, Journal of Retailing 70: 97–113.

- Kaufmann PJ, Stanworth J (2002) The decision to purchase a franchise: A study of prospective franchisees. Journal of Small Business Management 33: 22.

- Peterson A, Dant R (1990) Perceived advantages of the franchise option from the franchisee perspective: Empirical insights from a service franchise, Journal of Small Business Management 28: 46–61.

- Stanworth J, Purdy D (1994) The Blenheim / University of Westminster Franchise Survey No. 1. London, England: International Franchise Research Centre, University of Westminster.

- Stanworth J (1977) A Study of Franchising in Britain. London, England: University of Westminster.

- Knight RM (1986) Franchising from the franchisor and franchisee points of view, Journal of Small Business Management 25: 8–15.

- Withane S (1991) Franchising and Franchisee Behavior: An Examination of Opinions, Personal Characteristics, and Motives of Canadian Franchisee Entrepreneurs, Journal of Small Business Management 29: 22–29.

- O’Connor DE, Faile C (2000) Basic Economic Principles: A Guide for Students. Publisher: Greenwood Press, Westport, CT.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A (2007) Selling Blue Elephants: How to Make Great Products that People Want Before They Even Know They Want Them. Pearson, New York.

- Box GE, Hunter JS, Hunter WG (2005) Statistics for experimenters: design, innovation, and discovery (Vol. 2). New York: Wiley-Interscience.

- Cohen GJ, Cohen P (1983) Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. Hillsdale, New Jersey London.

- Keren C, Lewis G ED (1993) A Handbook for Data Analysis In The Behavioral Sciences: LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. Hillsdale, New Jersey London.