Short Commentary

The world of health policy and public health considers the health of women an important topic of focus, and in most cases link the well-being of women to that of children and the family, and, legitimately, to the health of society overall. More over the emphasis is more given to maternal and child health. This perspective is true and well-founded given that women health is well documented to promotion of the general health of family and everyone in society. The researcher however notes the otherwise limitation in promoting the general well-being of women across the divides in the society.

Women offenders fall among the special population groups in our society with dare need for attention towards their overall well-being. Unfortunately, very few studies have focused on who they are and reasons for their incarceration. In fact, the Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) model of offender rehabilitation [1] that has dominated rehabilitation programs globally in the last two decades provides the impression that reasons for criminality in women offenders are similar to those of their male counterparts, but the limited studies on incarceration of women has noted the assumption as erroneous. Thus, globally, the focus of rehabilitation programs for women offenders has often mirrored that of male offenders [2,3].

According to the study “Gender Responsive Programming in Kenya: Time is Ripe!” the researchers concluded that serious attention is needed in the rehabilitation of women in correctional facilities not only to help them to reform but to promote their mental well-being. The study noted that women have their distinct psychological needs associated with their criminal behaviors that rehabilitation programs must address. However, most governments and policy makers in the entire criminal justice system across the globe, Kenya included tend to focus more on reduction of recidivism in the women offenders through punishment, but with little focus on treatment of specific psychological needs that contribute to women’s offending behaviors.

Feminist psychologists working within the criminal justice system, e.g. (Van Voorhis and Salisbury, 2014) [4] proposes that rehabilitation within the correctional facilities should focus on restoration of offenders to useful lives through therapy, education and/ or training with the aim of promoting the psychological well-being of the individual to be rehabilitated. Their argument infers to the fact that informed rehabilitation practices is important rather than “punishment” of the offenders that tend to dominate most correctional programs.

The study “Gender Responsive Programming in Kenya: Time is Ripe!” was informed by two theories. The first one was the (RNR) model of offender rehabilitation developed by [5] emphasized the critical need of assessment of needs of offenders. Thus, for women offenders, there is need to assess psychological issues that contributed to offending through validated instruments to ensure that treatment can be matched to their actual needs and therefore promotion of entire well-being. This is well demonstrated in the second theory that the study employed; the Relational Theory of Women’s Psychological Development which was coined by Miller et al. (1976) [6-10]. In summary the theory acknowledges the difference in the moral and psychological development of men and women. Feminist criminologists have adapted this theory in the understanding of women’s pathways to criminality and denotes that “connections,” often disturbed in the lives of women offenders, is a critical developmental need that has to be addressed in rehabilitation for women for their mental well-being and to heal from their other past experiences that relate closely to their offending tendencies.

Through the mixed method data collection and analysis, the above study confirmed that women’s reasons for incarceration were in most cases different from those of their male counterparts. The study addressed specific psychological needs in relation to women offenders in the women correctional facilities in Kenya, notably: victimization or histories of abuse which were traumatic in nature, parental distress, dysfunctional relationships, low self-esteem and reduced self-efficacy.

To briefly explain, victimization or histories of abuse in women offenders were mostly physical and sexual in nature. The abuses happened mostly in childhood and in their spousal relationships. Due to lack of comprehensive model of treatment of the impact of their experiences, most victims ended up suffering from adverse psychological reactions including posttraumatic stress disorder (PSTD), clinical depression, clinical anxiety, toxic stress etc. In their disturbed state of mind, and not being able to reason out better ways of dealing with issues, they in turn acted out in wrong ways associated with criminal behaviors such as, murder, child neglect, drug use.

Most women offenders suffered parental distress that was associated with lack of parental skills, lack of support from their spousal relationships and poverty. Most were not able to adequately provide basic needs for their families. Moreover, majority were uneducated and this contributed to their poor financial status since they could not acquire jobs or afford capital income to engage in any form of self-employment. As sole bread winners for their families, their struggle towards meeting their obligations to provide for themselves and families sometimes pushed them to criminal activities such as theft, fraud, child neglect that led to their incarceration.

A significant number of women offenders were equally incarcerated due to offenses associated with dysfunctional relationships. High number of cases of dysfunctional relationships were associated with spousal fights followed by family of origin disagreements. These ended into murder and man slaughter cases. The study revealed psychological distress in struggling with dysfunctional relationships as contributory factor to the choice to offending.

The study found that with the many challenges that women experienced in their day to day living, many of the women offenders had low self-esteem and highly reduced self-efficacy. The low self-esteem in women offenders was liked to crimes such as; fraud, manslaughter, prostitution. It was noted that both low self-esteem and self-efficacy seem to push women to crimes in the same way an elevated self-esteem and self-efficacy poses problems.

The mental well-being of women offenders cannot therefore be ignored in the rehabilitation practices. World Health Organization (WHO, 2022) [11] defines mental health as a state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make contribution to his or her community. The findings in regards to psychological needs of women offenders contributing to activities that translate to criminality suggested a major focus of mental health of women in rehabilitation and the entire criminal justice system.

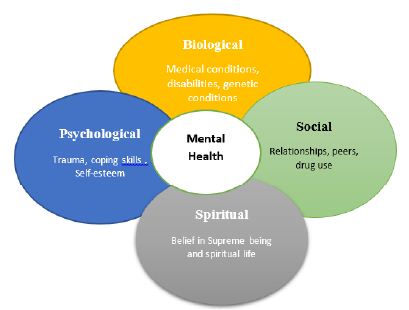

Most recently the researcher found it necessary to further develop this study by employing the biopsychosocial-spiritual model of illness and treatment in assessing the mental well-being of women offenders. The bio-psychosocial model was developed by George Engel and John Romano in the 1970s; noting that treatment of mental health denotes a multi-systems lens. The model recognizes the interaction between psychological, biological and social environment in illnesses. Therefore, treatment must focus on the different parts of the model. That is to say, an individual experiencing a psychological illness automatically suffers some biological illnesses and the social well-being of the person is equally affected. Other scholars have suggested the need for the fourth component, the “spiritual” component to be included in the model thus, the bio-psychosocial-spiritual model. The study found that the spiritual component is quite relevant as a majority of offenders observed that a spiritual life was important in developing resilience Figure 1.

Figure 1: An illustration of a biopsychosocial-spiritual model of treatment in the mental well-being of women offenders. Source: Researcher-adaptation.

A critical review of the bio-psychosocial-spiritual model of treatment promotes the principles of gender responsive programming in women’s correctional facilities thus applicable in ensuring the well-being of women prisoners. The recent investigation employed 4 focus group discussions within two maximum women’s correctional facility in Kenya. The findings confirmed a need to incorporate the biopsychosocial-spiritual model of treatment in view of gender responsive programming in women’s correctional facilities to promote the mental well-being of the offenders.

The researcher therefore recommends, based on the R-N-R model of offender rehabilitation that upon admission to the correctional facility, women offenders be screened and/or assessed to establish their unique psychological needs associated with their offenses. This will ensure placement into correct rehabilitation and treatment programs. It is important that governments ensure that the gender responsive programs are established. In view of the further development of the original study, it is important that treatment of women offenders be informed by the principles of biopsychosocial-spiritual model of treatment to ensure that the broad issues of the offender is addressed in rehabilitation. As already been observed such an approach will improve the mental well-being of the offenders alongside effective rehabilitation.

References

- Andrews DA, Bonta J, Wormith JS (2011) The Risk- Need Responsitivity model: Does the Good Lives Model contribute to effective crime prevention? Criminal Justice and Behavior 38: 735-755.

- Van Voorhis P, Wright EM, Salisbury EJ, Bauman A (2010) Women’s risk factors and their contributions to existing risk/needs assessment: The current status of a gender-responsive supplement. Criminal Justice and Behavior 37261: 288.

- Covington SS, Bloom BE (2008) Addressing the mental health needs of women offenders. In R. Gido and L. Dalley eds., Women’s Mental Health Issues Across the Criminal Justice System. Columbus, OH: Prentice Hall 160-176.

- Van Voorhis P, Salisbury EJ (2014) Correctional counseling and rehabilitation. USA: Anderson Publishing.

- Andrews DA, Bonta J (2004) The psychology of criminal conduct. Cincinnati, OH: Anderson.

- Miller JB (1976) Towards a psychology of women. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Gilligan C (1982) In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge. MA: Harvard University Press.

- Jordan J (1984) Empathy and self- boundaries. Work in progress No. 16. Welleslay, MA: Stone Center. Working Paper Series.

- Kaplan A (1984) The self- in relation: Implications for depression in women. Work in Progress No.14. Wellesley. MA: Stone Corner, Working Paper Series.

- Surrey J (1985) Self-in relation: A theory of women’s development. Work in progress No 13. Wellesley. MA: Stone Center, Working Paper Series.

- World Health Organization (2022) Mental Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.