Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this Quality Improvement (QI) project was to complete a formative evaluation of Trauma Informed Care (TIC) content delivered in a population-focused health nursing course for senior-level undergraduate nursing students.

Methods: This was a descriptive study that gathered feedback from students about the Trauma Informed Care content. A survey was disseminated via Qualtrics after the module/lecture to gather information about the effectiveness of the lecture with respect to TIC content; timing of the lecture in the semester relative to clinical; attitudes/perceptions about the importance of the content and practical application.

Results: The content provided to the students in Nursing 466 Community Health improved students’ knowledge and skills related to providing Trauma Informed Care. Twenty-five participants from the Bachelor of Science in Nursing program at Gonzaga University participated

Keywords

Bachelor of nursing students, Trauma-informed care, COVID-19, Population health

Introduction

Current times require us to reexamine the content we are teaching community/public health nursing courses. The American Association of Public Health suggests that undergraduate public health nursing education should include information on trauma-informed care. Trauma-informed pedagogy in public health is not new, but the trauma related to the COVID-19 pandemic argues for making it a priority for all educators [1]. As a result of the pandemic many in the public have experienced trauma related to stress, financial impact, mental health, and physical well-being. We are faced with increasing rates of the COVID-19 pandemic, chronic conditions, infections, violence, and extreme weather events. All these circumstances point to a growing need for including content about Trauma Informed Care. The concept of trauma can be described as the following “Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being [1]. This article reports the formative evaluation of adding content about Trauma Informed Care (TIC) to a population-focused health course in a Bachelor of Science (BSN) program at a private university in the inland northwest. Trauma-informed care is grounded in a set of four assumptions and six key principles as a framework. The four Rs of this Trauma-Informed Approach framework are: realize, recognize, respond, and resist re-traumatization [1]. “A program, organization, or system that is trauma-informed realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery; recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; and responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices, and seeks to actively resist re-traumatization (wording bolded in original text). These concepts are needed when working in population health. The content that was presented to this BSN group of students was organized into three sections. Section 1 was an overview of trauma-informed care, including the definitions of trauma and passive trauma. The trauma that those who experience homelessness or living in poverty were used as exemplars. This section included an overview of neurobiology, biopsychosocial needs of those experiencing homelessness, addiction, and/or poverty, and how the brain reacts to trauma. Section two described different types of traumas as a public health issue of our time and included an overview of Adverse Childhood Effects (ACEs). Exemplars of trauma related to ACES, as well as the pandemic, and natural disasters were presented. Section two also included an overview of current statistics related to trauma and how stress affects those that experience trauma. Section three addressed addiction, stress, and homelessness, how to return to a state of hope, how to implement and “do” trauma-informed care, transformation, and post-traumatic growth, and how not to re-traumatize individuals. Today we are not only faced with increasing diseases but also other traumatic events [2]. These events can be additional sources of trauma and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in public health. Although the need for nurses who can manage care along a continuum, implement evidence-based practice, work in multi-disciplinary teams, and integrate clinical expertise with knowledge of community resources is recognized, there is a lack of pedagogy that includes Trauma Informed Care [3]. This article describes the need for gathering formative information to add trauma-informed pedagogy to the current community health course. Using that formative information students provide could lead to changes made to the content before presenting it to the next group of students. The TIC content and knowledge could be implemented with the partnership between the school of nursing (SON) and local agencies where students complete public health clinicals.

Background

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is an essential need to prepare BSN students to not only care for individuals, but also for populations. According to SAMSHA “PHN practice is population-focused and requires unique competencies, skills, and knowledge. The important skills of analytic assessment, program planning, cultural competence, communication, leadership, and systems thinking, and policy are critical to the PHN role” [4]. Considering the pandemic, students’ interest may be piqued, and more students now see public health as a viable career option. It is important as faculty to recognize how Public Health will be taught in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and have awareness of the trauma students could experience as new nurses taking care of COVID patients. The pandemic will have likely affected students as well as those prone to experience trauma among the population on a personal level either because they have become ill themselves or know someone that was affected by the virus. Furthermore, we need to consider the trauma of providing nursing care as a student to COVID patients. With this comes the need for trauma-informed care. Those from marginalized communities, the homeless population, and middle-class families have all been prone to traumatic experiences. Trauma Informed Care will ensure that the students gain knowledge and learning tools to serve their community with the knowledge of what Trauma Informed care is and how to reduce the risk of re-traumatization of clients [3]. The added pedagogy included Trauma Informed Care, to an already packed course that includes Disaster Preparedness, prioritizing social determinants of health, and the use of politics and policy. As faculty teaching, this group of “post-pandemic” students requires our pedagogy to include trauma-informed care so as to not exacerbate the client’s trauma in their public health clinicals’. The students at this school of nursing work in partnership with community sites such as shelters, homeless centers, the department of health, and many other agencies that provide services to populations that experience extreme poverty. The content took on a hybrid format of teaching online and in the classroom. Study findings provide information to inform revisions to the lecture to better meet the needs of students regarding this content.

Problem

Undergraduate Nursing students in this BSN program need Trauma Informed Care content. There is a gap in practice in the literature regarding Trauma Informed Care (TIC) taught in the BSN program. As a result of the COVID-19 Pandemic, many in the public may have experienced some form of trauma. There is a recurring recommendation from the American Public Health Association to start integrating TIC into the undergraduate curricula to educate BSN students on what Trauma Informed Care is and how to apply it to practice. This Quality Improvement Project aimed to examine the formative feedback and perceived value of the TIC content integrated into the BSN Community Health content.

Methods

This was a descriptive study within one BSN program. Students were enrolled in the senior-level community health class. Participation was voluntary and consent, as well as understanding the purpose and process of this project, was presumed by completion of the survey. Approval from the university’s IRB was obtained. The survey included both scaled and open-ended questions and students could voluntarily participate post-lecture. This article describes the preliminary findings of the perceived value of the TIC content and how students responded to the content delivered. The overall goal was to gather feedback about the effectiveness of the lecture and what changes need to be made for the future integration of TIC into the community health course. Participants were invited to participate in a Qualtrics survey sent out securely to their student email addresses during class by a staff member from the Dean’s Office. The investigator did not utilize email addresses herself but had the staff member send the surveys via email during class time from a remote location. The class roster was available to the staff member in the university system. Email addresses were not stored in any other system except for Qualtrics, the survey software. Once the survey and project were completed using Qualtrics, any email addresses used by the system were deleted. The investigator/course instructor informed the class (potential subjects) about the survey and study goals immediately before the lecture was given and informed the students of their ability to opt-in/out of the survey portion of the class, which occurred after the lecture was given. The survey consisted of 9 questions Likert-type scaled responses and 5 open-ended questions that were designed to gather feedback about the effectiveness of the lecture with respect to content; timing of the lecture in the semester relative to clinicals’; perceived importance of the content and practical application; information necessary to inform revisions to the lecture to make it tailored to the population-level needs of the students A Likert scale was used to gather quantitative data. Five of the questions were open-ended so that the students could provide written feedback exploring contextual factors [5,6]. Students’ narrative responses provided essential information about how to format the content and presentation for the next group.

Results

The Trauma Informed Care content is particularly valuable. This information also provides resources and tools for clinical practice use. The formative evaluation process used in the project provided valuable feedback to increase the quality of this content and delivery in the future to the next group of participants (students). The content provided to the students in Nursing 466 Community Health improved students’ knowledge and skills related to providing Trauma Informed Care. Twenty-five participants from the Bachelor of Science in Nursing program at Gonzaga University participated. Participating evaluators indicated that the education program was effective with respect to TIC content, the timing of the lecture in the semester relative to clinical, attitudes/perceptions about the importance of the content and practical application. Overall, 52% of participants felt the content was very understandable and 64% felt the content was very important to clinical practice. 56% of participants felt that the lecture was very understandable and 64% of the participants felt that the content was important to clinical practice. Participants (54%) felt that the content was usable in their practice and 44% of participants felt that it would impact their values and beliefs.

Demographics

Thirty-six students were enrolled in the course; 25 (69%) of participants completed the survey. This section outlines descriptive statistics performed for the Likert-type items that were a part of the questionnaire. To capture the students’ perceptions about the lecture, we included in the questionnaire questions such as “How informative was the lecture content” and “How relevant is this lecture to public health.” These questions were measured utilizing a Likert-type scale ranging. 0=Unimportant, 1=Somewhat important, 2=Moderately important, 3=Important, 4=Very important, 5=I don’t know.

Qualitative feedback identified strengths in the use of the open-ended questions related to how the lecture impacted the students’ values and beliefs about people who live with homelessness and substances; the length of the presentation; timeliness of the presentation; understandability of the lecture and lastly, what changes the participants suggested to improve the lecture for future students

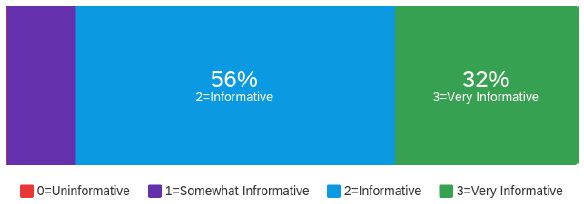

14 (56%) of respondents indicated that they found the lecture content to be informative, while 8 (32%) found it very informative. 21 (84%) of respondents found the lecture to be very relevant to the landscape of public health (Graph 1).

Graph 1: How informative was the lecture content

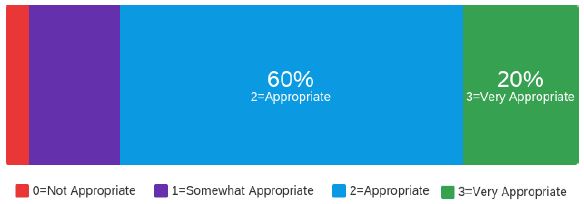

The students were asked to assess the length of the presentation. There were 25(60%) respondents that found the length of the presentation appropriate, while 5(20%) found it very appropriate (Graph 2).

Graph 2: Length of lecture

From this question, four different themes came to light. These themes are “different parts of the lecture “extending the lecture” “reduction in the lecture” and “additions to lecture.

The lecture was split up into three different sections and the students responded favorably to this and stated that “the presentation blended well together, and each section built off one another in a coherent manner”. There were some comments to extend the lecture by including more breaks and breaking apart what trauma-informed care is based on evidence-based practice and how that can be implemented in different communities. Related to the reduction in lecture the lecture was very consolidated, and students felt that there were a few slides that could be omitted. Some students suggested that perhaps it could be a multiday lecture. Additions to the lecture included suggestions to add some more videos and to include the ACE’s resources and some CDC resources.

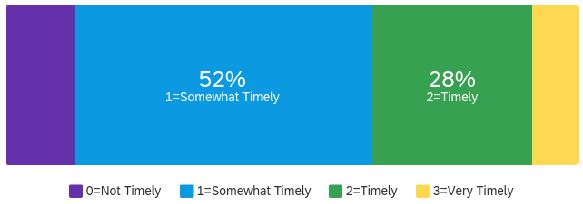

The timeliness of the lecture relative to the student’s clinical experiences was also assessed. There were 13 (52%) respondents that indicated that the lecture was somewhat timely;7 (28%) of respondents rated it as timely with respect to how early it was offered in the course (Graph 3).

Graph 3: Timeliness of the lecture

Timeliness was very important to the students, and they noted that it would be good for students to benefit from the content much earlier in their BSN curriculum. Students suggested receiving this content earlier in the semester of their program. It was stated that if they had this before their senior practicum it would be very beneficial. Others stated that they could see this content being threaded throughout their 4-year program. It was mentioned that trauma-informed care is something they are thankful they learned in their BSN track and wished to learn about it earlier.

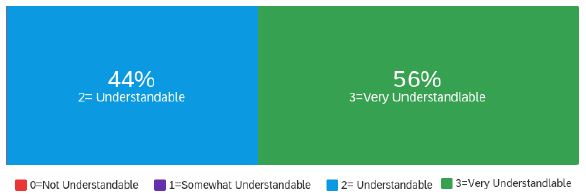

To assess the impact of the lecture, the following questions were asked: “How understandable was the presentation?” 14 (56%) Respondents felt the presentation was very understandable (Graph 4).

Graph 4: How understandable was the lecture

In response to this question Students mentioned that the topic was very relevant and helped them to see the “bigger picture”. Furthermore, they stated it would help them to identify paying attention to the information relating to ACEs among children, and being able to be an advocate for their patients was very important and helpful. Regarding the enjoyability of the lecture, students felt the PowerPoint was easy to follow and enjoyable to view.

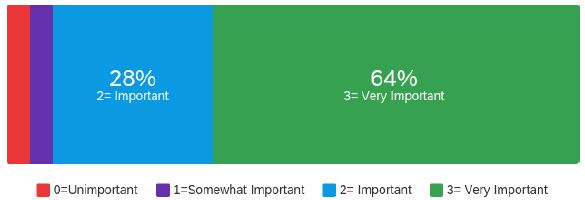

“How important will this lecture be to your clinical practice,” 7 (28%) respondents felt that this was very important content for their clinical practice. 16 (64%) of respondents felt that this was very important content for their clinical practice (Graph 5).

Graph 5: Importance of lecture to clinical practice

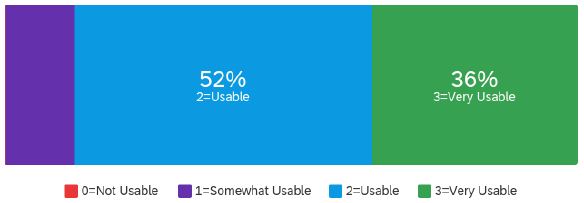

“To what extent do you feel the content can be used by you in practice immediately?” 9 (36%) of respondents felt that the content could be used in practice immediately. 13 (52%) respondents felt that the content was usable for practice immediately (Graph 6).

Graph 6: Usability of lecture in practice

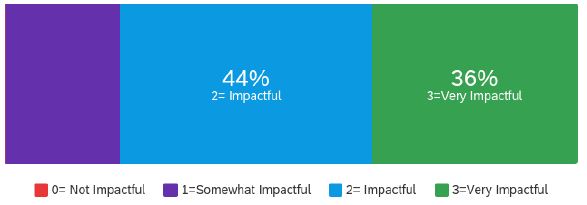

“To what extent did the lecture content impact your values and beliefs about people who live with homelessness and use substances?” 9(35%) of respondents felt that the content was very impactful and related to the above question. 11 (44%) of respondents felt it was impactful content (Graph 7).

Graph 7: Impact on values and beliefs

The first question analyzed reflects the impact that the content on the student’s values and beliefs about how people live with homelessness and substances. Students stated that the content was “extremely relevant” and is a significant component in promoting healing. Furthermore, students stated that “being educated on this topic allows us to be more aware and educate the community we work with during our community health clinical’ as future nurses, and it provides details about the struggles the homeless face since many of those experience some form of trauma that have been homeless before.” There were two sub-questions to this overall question.

- The next question addressed what students’ reaction was to the details about physiological and psychological content. Students responded that neurological and biological changes are important to consider and that it was “cool” to learn more about the actual physiology and physical and chemical changes that occur during trauma. Furthermore, it was stated that “the lecture did a really good job at explaining the reasoning behind homelessness and addiction”.

- Understanding what Adverse Childhood Effects (ACEs) are, was another area of this question that could influence the values and beliefs. Students state that understanding ACES “impacts the way you interact with patients in the clinical setting and broadened their perspective and strengthened their patience while working with this population and/or people who may have experienced ACEs or trauma in the past.

What changes would you make to the TIC lecture to improve it for future NURS 466 students? This question addressed any suggestions or changes to the lecture. Three themes emerged including resources, timing, and methods. Students suggested that they could offer specific resources or reference for patients or clients. They also asked how they can be sure to not re-traumatize patients. One of the students suggested asking someone who experienced trauma and overcame it to write a letter and share how they overcame their trauma. Timing again addressed the fact students wanted this content earlier in the semester, and program. Regarding methods, students mentioned more class discussions and asked for some real-life clinical examples. They also suggested part of the lecture be more interactive and include discussion.

Outcomes

Participating evaluators indicated that the education program was effective with respect to TIC content, the timing of the lecture in the semester relative to clinical, attitudes/perceptions about the importance of the content and practical application. Receiving formative evaluation to improve the development of a trauma-informed public health education program that provided evidence-based strategies and resources was the primary goal of this project. The results of the program demonstrated the effectiveness of using formative evaluation to develop a trauma-informed educational lecture for senior undergraduate Bachelor of Nursing students. The educational lecture overall demonstrated positive responses as to how the lecture impacted the students’ values and beliefs about people who live with homelessness and substances; the length of the presentation; timeliness of the presentation; understandability of the lecture and lastly, what changes the participants suggested to improve the lecture for future students. The findings of this educational lecture resonate with findings from other publications in relation to the importance of educational content on trauma-informed care for undergraduate nursing students to equip students with knowledge and understanding of trauma-informed care as it relates to public health. Emphasis on how timely this lecture was given is noted and will help change the timeliness of future lectures provided at the beginning of the student’s semester rather than toward the end.

Limitations

While the development of this Trauma-Informed care lecture reasonably provides strong evidence of the effectiveness of using formative evaluation to aid the development of the lecture within the sample population, it has some limitations. The first limitation is that it did not provide pre- and post-feedback as to what knowledge base the students had related to the content. It was limited only to one class in the undergraduate nursing program and the feedback is provided at the end of class when students are overloaded with the information they just received.

Future Directions

To overcome some of the limitations the respondents in the next part of this project will have a pre-and post-survey. The formative information provided in this project will better the lecture offered to the next student group in the Spring 2021 semester.

Funding

There was no funding involved for this project.

Conclusions

The trauma-informed care for public health lecture developed for senior undergraduate nursing students is powerfully applied by using evidence-based content and resources poised to provide an excellent delivery system for educating students. The lecture provided students with evidence-based content related to how trauma-informed care impacts public health. The student participants’ responses to the formative evaluations in developing this content were positive. In addition, the responses provided positive feedback and suggestions to improve the development of this lecture for future students.

References

- SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach (2014) Retrieved from Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Auerbach, J, Miller F (2020) COVID 19 Exposes the cracks in our already fragile mental health system. AJPH. [crossref]

- Abuelezam N (2020) Teaching public health will never be the same. AJPH 110. [crossref]

- National League for Nursing. NLN. 2022.

- Center for Disease Control. CDC. 2021.

- S Department of health and human services (HHS) (2014) Office of women’s (OWH) health trauma informed care (TIC) training and technical assistance initiative. Participant scales. Cross-site evaluation of the national training initiative on trauma informed care (TIC) for community-based providers from diverse service systems. Abt. Associates.