Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to clarify the difficult situations experienced by Japanese nurses, their responses to these situations, the relationship between the factors causing these difficulties and the degree of difficulties, and to examine the support needed by nurses.

Methods: A self-administered, unsolicited questionnaire survey was conducted among Japanese nursing professionals via the web to collect data on situations in which they experienced difficulties in their daily practice, including their frequency, degree of difficulty, and coping methods. Descriptive statistics were calculated.

Results: The top difficulties experienced by nurses were “communication with patients/users,” “coordination among nurses,” and “communication with patients’/users’ families.” The difficulty level of “coordination among nurses/multi-professionals” was significantly higher, and many respondents had experienced job turnover or a leave of absence. While the majority of respondents consulted within the workplace, there were difficulties in “coordination among nurses.”

Conclusions: Japanese nurses experienced a high frequency of difficult situations with a high degree of difficulty. For “coordination among nurses/ coordination among other professions,” which was particularly challenging, it is necessary to implement organizational measures, such as the development of an organizational structure and support for the coordination of human relationships. On the other hand, it was suggested that there is a need for support to obtain hints for self-help solutions outside the workplace, such as through internet searches.

Keywords

Nurses, Difficulty, Japan, Turn over

Introduction

The nursing shortage is a problem that is occurring all over the world. If left unresolved, it is a problem that can seriously affect the delivery of quality healthcare [1]. Frequent turnover of nurses in hospitals leads to reduced staffing levels, which negatively affects the quality of care and patient safety [2]. Many countries are therefore attempting to address the nursing shortage, and it has been found that the most effective strategy is to maintain the current workforce [3]. In Japan, nursing practice is becoming increasingly sophisticated and complex, and nurses are faced with a variety of difficult nursing situations. The distress caused by nurses’ job-related difficulties affects their retirement, professional development and the quality of nursing practice [4]. Therefore, we considered it necessary to identify the difficulties nurses face in their daily practice and how they cope with them, and to support them to continue working. This study was conducted with the aim of identifying the difficult situations experienced by Japanese nurses and their responses and the relationship between the factors causing difficulties and the level of difficulty, and to examine the support needed by the nursing profession.

Methods

Design

This study utilized fact-finding research through distribution surveys.

Data Collection

The survey was conducted on 500 Japanese nursing professionals (nurses, public health nurses, and midwives) registered as monitors with a web-based research company and working in medical facilities, home nursing stations, government agencies, and companies. Sample size was calculated based on literature review. A self-administered, anonymous questionnaire was used to collect data on personal background and “difficult situations experienced by nurses. “For personal background, questions were asked mainly about the type of occupation/years of experience/position/place of work/age/gender in which they are engaged. For the “difficult situations experienced by nursing professionals,” a framework was developed and a questionnaire was constructed to reflect the literature and the real voices of nursing professionals by identifying situations that were perceived as more difficult than the SNS. A pretest of this questionnaire was conducted with nursing faculty members to confirm the content, order of questions, and consistency. The questionnaire items were problem-solving when troubled or distressed in daily practice (coping methods/frequency of troubled experiences/experience of leaving or taking a leave of absence), situations in which the respondents felt difficulties in daily practice (subject of difficulty/characteristics of the subject/scenario/free description of the scene/free description of the response/degree of difficulty), degree of difficulty felt (enter “10” for difficulty to quit immediately and “1” for difficulty that is not a problem), and symptoms caused by the response to difficult situations. Data were collected from 15-22 December 2023, when a web-based survey was commissioned to a web-based research company.

Data Analysis

Data on situations in which participants experienced difficulties in daily practice, their frequency, degree of difficulty, and coping methods were collected, and descriptive statistics were calculated. Additionally, the χ² test and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient were calculated using SPSS Ver. 28.

Ethics

The purpose, methods, and ethical considerations of the study were explained to the subjects on the web screen, and their consent was deemed to have been given upon submission of their responses. The survey was anonymous, and the results were managed using identification numbers to ensure that individuals could not be identified. Information will not be used for any purpose other than the research, and data related to the survey will be strictly managed by the researcher. The study was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Review Committee of Kawasaki City College of Nursing.

Results

Overview of the Subjects

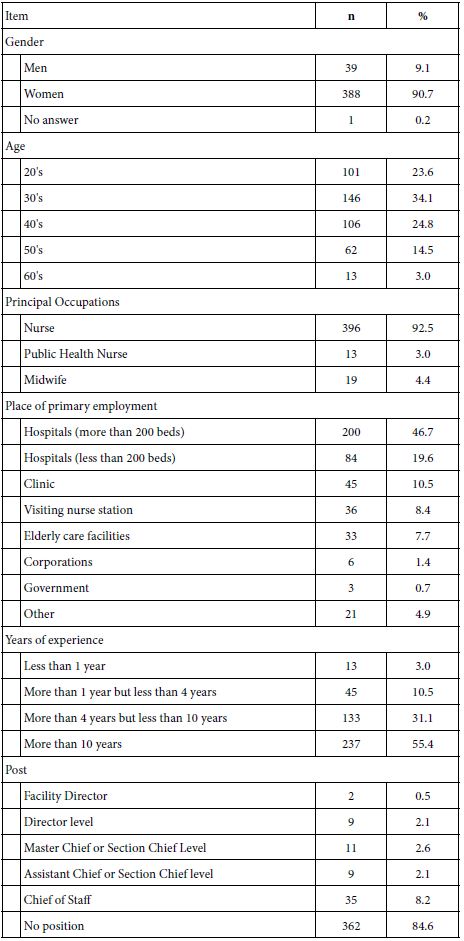

Responses were obtained from 428 Japanese nursing professionals. The study subjects ranged in age from 20s to 60s. 396 (92.5%) were nurses, 13 (3.0%) were public health nurses, and 19 (4.4%) were midwives (Table 1).

Table 1: Demographics of the participating patients (n=428).

Difficult Situations Experienced by Nurses

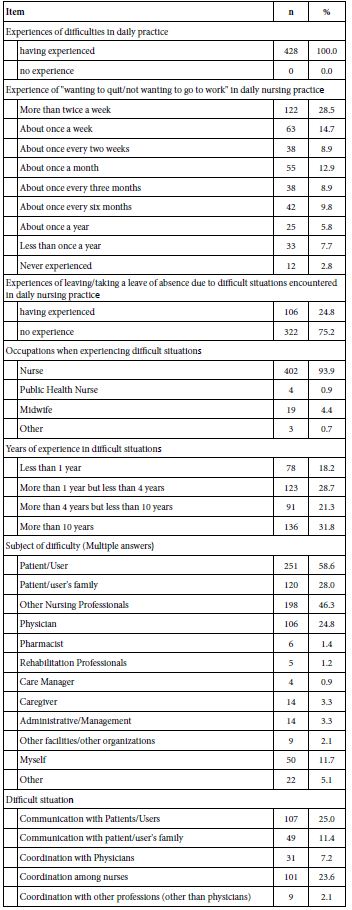

All 428 (100%) experienced difficulties in practice, and 122 (28.5%) most frequently experienced “wanting to quit/not wanting to go to work” because of these difficulties, at least twice a week, followed by 63 (14.7%) about once a week. The top difficulties were “communication with patients/users” (107 respondents, 25.0%), “coordination among nurses” (101 respondents, 23.6%), “communication with patients’/users’ families” (49 respondents, 11.4%), and “practical skills (nursing techniques, etc.)” (37 respondents, 8.6%). When the level of difficulty was defined as “10” for wanting to quit immediately and “1” for no problem, 87 (62.8%) of the respondents rated the difficulty as “7” or more, and 106 (24.8%) indicated they had “left/took a leave of absence” due to the difficulty. To solve their problems, 306 (71.5%) responded “consulting with a senior colleague,” 289 (67.5%) “consulting with a supervisor,” 277 (64.7%) “consulting with a peer,” and 222 (51.9%) “searching the Internet.” The most common symptoms caused by dealing with difficult situations were fatigue/exhaustion (291 respondents, 68.0%), depression (254 respondents, 59.3%), and anxiety (227 respondents, 53.0%) (Table 2).

Table 2: Outline of difficulties experienced in daily nursing practice (n=428).

Difficulties, Degree of Difficulty, and Experience of Leaving the Workplace or Taking a Leave of Absence

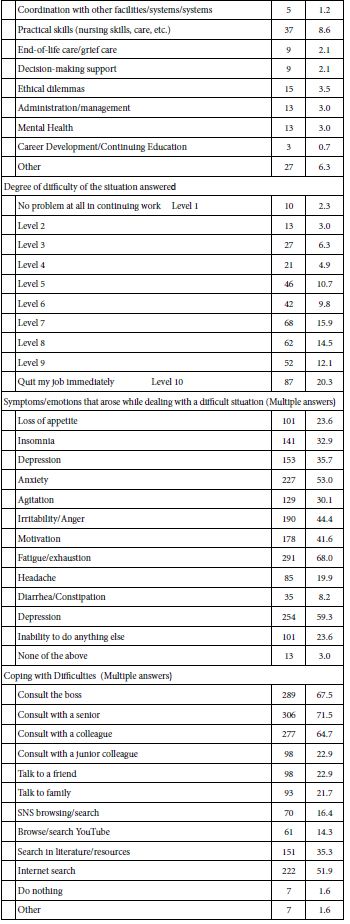

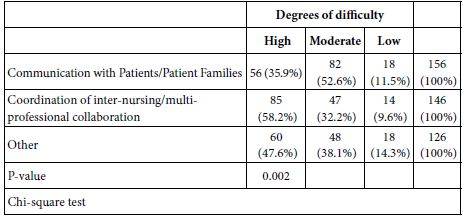

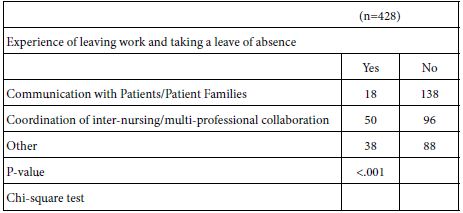

A χ² test was conducted on the content of difficulty and the degree of difficulty. The results showed that the content of difficulty related to “communication with patients/patients’ families” was significantly associated with a Moderate degree of difficulty (p=.002), while the content of difficulty related to “coordination among nurses/ multiprofessionals” was also associated with a moderate degree of difficulty (p=.002) (Table 3). There was also an association between the content of difficulties and the experience of leaving/taking a leave of absence (p<.001), with more respondents having left/taken a leave of absence for “coordination among nurses/multidisciplinary staff ” and fewer respondents leaving/taking a leave of absence for “communication with patients/patients’ families” (Table 4).

Table 3: Difficulty Description and Degree of Difficulty (n=428).

Table 4: Description of hardship and separation leave (n=428).

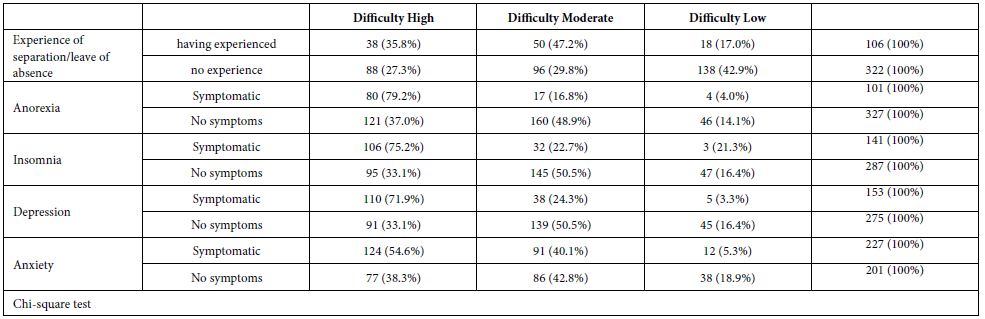

Difficulty Level, Experience of Leaving Work/Taking a Leave of Absence, and Psychosomatic Symptoms When Experiencing Difficulty

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was calculated for the degree of difficulty and frequency of not wanting to go to work, and a significant correlation was found (p<.001, r=.263). There was also a relationship between the level of difficulty and whether or not the respondent had ever left work/taken a leave of absence, with those that had never left work or taken a leave of absence having significantly lower levels of difficulty (p<.001). Associations were found for Anorexia, insomnia, depression, and anxiety (p<.001), and those with higher levels of difficulty experienced more physical and mental symptoms with job turnover/leave of absence. (Table 5).

Table 5: Degree of difficulty and experience of separation/leave of absence from work and psychosomatic symptoms physical symptoms (n=428).

Discussion

The most challenging situations experienced by the nursing professionals were “patient/user communication,” “coordination among nurses,” and “communication with patient/user families. All of these were relationship issues surrounding the nursing profession, suggesting the need for training support in relationship coordination. The nurse-patient relationship is the basis of nursing care, a helping relationship built with patients and their families based on interaction, communication, respect for ethical values, acceptance, and empathy. Communication to establish the helping relationship, like other nursing skills, requires a special training process [5]. In addition to this basic communication, patient/family harassment and ‘difficult patients’ must also be addressed. About a third of nurses worldwide indicated exposure to physical violence and bullying, about a third reported injury, about a quarter experienced sexual harassment, and about two-thirds indicated nonphysical violence [6]. In the nurses’ view, the ‘difficult patients’ had little insight into their illnesses, denied they were ill and were noncompliant [7]. Contributing causes of patients becoming difficult for nurses seemed to be different norms and values and the nurses’ work situation [7]. When there is such unreasonable communication from patients and families, it is necessary to take organizational measures in addition to communication training for individual nurses.

Since the difficulty in “coordination among nurses/other professions” was higher than that in “communication with patients/ patients’ families,” and since there was a high rate of turnover/leave from work, it is necessary to focus on this area. The most common style used by nurses overall to resolve workplace conflict was compromising, followed by competing, avoiding, accommodating, and collaborating [8]. Thus, coordination among nurses is difficult when individual nurses are dealing with this issue, and the team needs to consider improvements. Enhanced team communication may strengthen nurses’ attachment to their organizations and teams and improve nurse retention [9]. When nurses feel psychologically safe at work, they are more likely to engage in open communication, which in turn can lead to greater job satisfaction, decreased turnover intention, and improved patient safety [10]. Effective communication, respect, and proper recognition are among the main strategies that senior leaders can use to retain nurses [11]. Therefore, it was suggested that there is a need to enhance educational content for managers related to improving the workplace environment to enhance psychological safety in the workplace, such as organizational structure and support for adjusting human relations, as well as communication skills and other educational content that can be used for coordination and collaboration. In addition, those with high levels of difficulty experienced many physical and mental symptoms, suggesting the need to work on self-care and to talk to each other to see if nurses who complain of physical or mental illness have any difficulties. On the other hand, those with low levels of difficulty often consulted their junior colleagues, suggesting a situation in which the consulting partner is selected according to the level of difficulty and that countermeasures can be obtained from a wide range of partners. In addition, while the majority of the respondents consulted within their workplaces in terms of coping methods, they still face difficulties in “coordination among nurses,” suggesting the need for support in obtaining hints for solutions through “Internet searches” and other means outside of the workplace.

A limitation of this study is the small sample size of the Japanese nursing workforce. However, the fact that the study was unique in that it covered the entire range of situations that nurses may encounter and systematized the survey in a cross-sectional manner makes it desirable to conduct future surveys with larger sample sizes.

Funding

Supported by JST Co-Creation Field Formation Support Program (JPMJPF2202). Part of this study was presented as a poster presentation at the 50th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society of Nursing Research.

References

- Chan ZC, Tam WS, Lung MK, Wong WY, Chau CW (2013) A systematic literature review of nurse shortage and the intention to leave. J Nurs Manag 21: 605-613. [crossref]

- Antwi YA, Bowblis R (2018) The impact of nurse turnover on quality of care and mortality in nursing homes: Evidence from the great American Journal of Health Economics. 4: 131-163.

- Wu F, Lao Y, Feng Y, Zhu J, Zhang Y, et al. (2024) Worldwide prevalence and associated factors of nursing staff turnover: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurs Open. 11.

- Risako Takahashi, Toshiko Nakayama, Mamiko Ueda et al. (2022) Experiences of Hospital Nurses Who Resigned from Employment Citing Job-Related Difficulties. Nursing Education Research.31: 43-56.

- Allande-Cussó R, Fernández-García E, Porcel-Gálvez AM (2022) Defining and characterising the nurse-patient relationship: A concept analysis. Nurs Ethics. 29: 462-484. [crossref]

- Spector PE, Zhou ZE, Che XX (2014) Nurse exposure to physical and nonphysical violence, bullying, and sexual harassment: a quantitative Int J Nurs Stud. 51: 72-84. [crossref]

- Michaelsen JJ (2021) The ‘difficult patient’ phenomenon in home nursing and ‘self- inflicted’ Scand J Caring Sci. 35: 761-768. [crossref]

- Losa Iglesias ME, Becerro de Bengoa Vallejo R (2012) Conflict resolution styles in the nursing profession. Contemp Nurse. 43: 73-80. [crossref]

- Apker J, Propp KM, Ford WS (2009) Investigating the effect of nurse-team communication on nurse turnover: relationships among communication processes, identification, and intent to leave. Health Commun. 24: 106-114. [crossref]

- Cho H, Steege LM, Arsenault Knudsen ÉN (2023) Psychological safety, communication openness, nurse job outcomes, and patient safety in hospital Res Nurs Health 46: 445-453. [crossref]

- Duru DC, Hammoud MS (2022) Identifying effective retention strategies for front- line nurses. Nurse Manag (Harrow) 29: 17-24. [crossref]