Abstract

Using AI embedded in a user-friend platform (www.bimileap.com) it became possible to request new knowledge rapidly and easily about mind-sets dealing with accusations of genocide against Israel. Given only requests to identify mind-sets and suggest their beliefs and relevant communications, the AI embedded in the platform provide concrete, testable recommendations in a user-friendly form easily understood, as well as AI-summarizations of its own recommendations. The process, taking only minutes, is recommended as a new thrust for understanding conflicts, and improving the current world order.

Introduction

The tragic events of October 7, 2023, in the southern part of Israel culminated in the deaths of more than 1200+ Israelis and others attending an outdoor concert/festival. The military response of Israel against Hamas resulted in a widespread destruction of much of Gaza and the deaths of many people. The response of many students around the world was to support Gaza, and to claim that a genocide was being committed. Many university students around the world protested, wearing the black and gray keffiyehs which have come to symbolize the Palestinian fight against Israel. During this time, the increasing level of accusation reached unheard of proportions in the modern world as antisemitic tropes and canards emerged about Jews and their so-called activities. The remarkable ferocity of the accusation requires an understanding of how to deal with the hostility.

The Contribution of Mind Genomics

The approach here comes from the emerging science of Mind Genomics. Mind Genomics studies the way people make decisions about the issues of the everyday, such as what they will purchase in a store, what kind of service they want from a physician or lawyer or other professional, and so forth. Rather than doing experiments to understand specific things such as the way people process information, Mind Genomics works at the level of granular, everyday experience, attempting to understand how people think about the specifics of their lives. Mind Genomics can thus be thought of as the science of everyday experience [1-3].

Moving to Detailed Instructions Given to AI

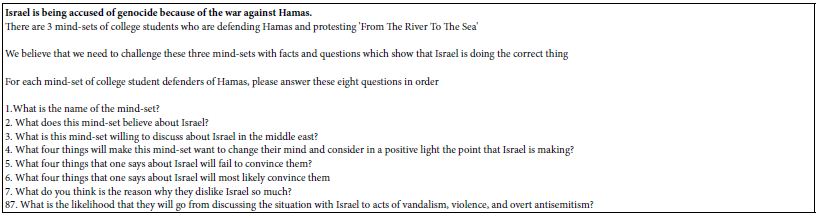

The AI embedded in Idea Coach allows the user to pose more complicated questions. The questions move from simply questions to statements, actually hypotheses, and then pose questions based upon the hypotheses. Table 1 shows the instructions provided to Idea Coach in the www.bimileap platform. The instructions posit the existence of three mind-sets, although the instructions could have been changed to posit fewer or more. Previous work investigations with Mind Genomics often revealed that three mind-sets generated both a comprehensive coverage of different points of view on the topic but at the same time generated a feeling of parsimony. That is, three mind-sets satisfied both the need to cover the different points of view, but the desire to do with as little hypothesizing as possible. After introducing the topic, the request asked eight specific questions, all of which required the AI to hypothesize about what might be the case for each mind-set. The final piece of information was the group about whom the request was being made, specifically college students.

Table 1: The request as given to Idea Coach

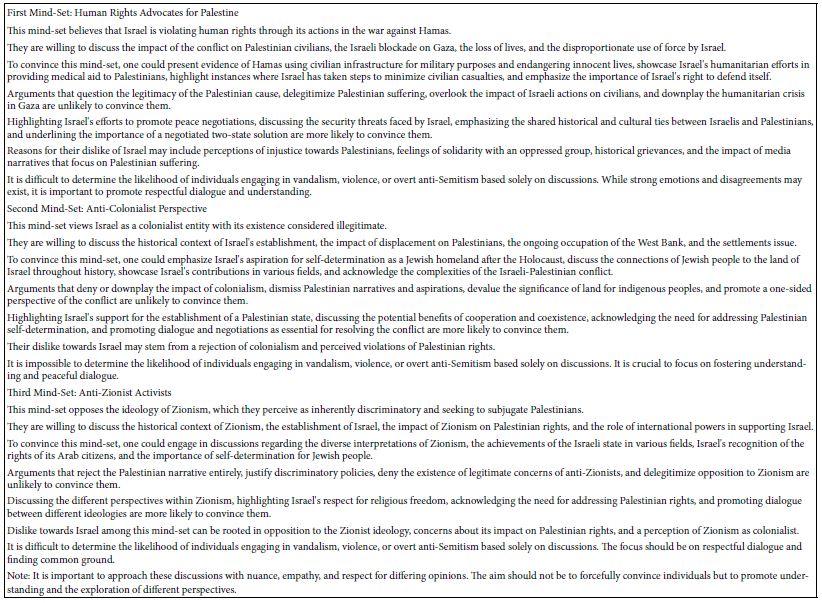

As requested, Idea Coach returned with three mind-sets, shown in Table 2. These mind-sets are:

- Human rights advocates for Palestine

- Anti-colonialist perspective

- Anti-Zionist activists

Table 2: Specifics of the three mind-sets returned by the AI in Idea Coach

It is instructive to keep in mind that there is nothing provided to the AI to suggest these three groups. Rather, it is the AI which generates the three mind-sets. It is also interesting to note that repeated efforts with AI will return with different sets of mind-sets. That is, for whatever reason, the answers may not be repeatable. That is, it appears almost the a similar but not the same person is thinking through the problem, so that the general patterns are repeated, but not specifics. The AI returns with sets of answers which appear to be internally consistent and agree with the name of the mind-set. There are two disclaimers.

Question #7: What is the likelihood that they will go from discussing the situation with Israel to acts of vandalism, violence, and overt antisemitism?

Answer to Question #7: It is difficult to determine the likelihood of individuals engaging in vandalism, violence, or overt anti-Semitism based solely on discussions. While strong emotions and disagreements may exist, it is important to promote respectful dialogue and understanding.

General disclaimer: Note: It is important to approach these discussions with nuance, empathy, and respect for differing opinions. The aim should not be to forcefully convince individuals but to promote understanding and the exploration of different perspectives.

Table 2 presents the specifics for the three mind-sets returned by the AI in Idea Coach. The table shows the specifics for these three mind-sets. It is important to emphasize here that mind-sets presented in Table 2 are strictly those ‘conceptualized by the AI’. What is important here is that AI returns results that are similar to what a human being might provide, or at least are plausible answers. In a Turing Test one might assume that these answers would defy the attempt of a person to know whether results are generated by machine or generated by people, especially if one were to ignore the language and focus just on the ‘information’ provided.

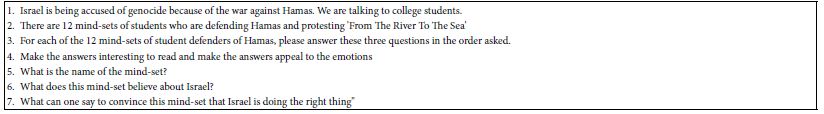

The initial ‘success’ in the process encouraged the use of AI to move further into the possibilities of looking at the topic in deeper granularity. Rather than instructing Idea Coach and its AI to assume three different mind-sets, the second part of effort ‘pushed the envelope’ to an arbitrary set of 12 different mind-sets. Table 3 shows the instructions to Idea Coach, positing the existence of these 12 mind-sets of students. The task assigned to Idea Coach was made simpler because initial efforts to have the AI answer seven questions for each of 12 mind-sets proved too difficult. The AI returned with a polite refusal each time the large request was made. It was easier simply to ask three questions, comprising name of mind-set, belief about Israel by mind-set, and finally the action step of ‘what does one say to convince this mind-set that Israel is doing the right thing?’ These steps were immediately acted upon by the AI in Idea Coach.

Table 3: The questions asked in the second phase, where 12 mind-sets were posited

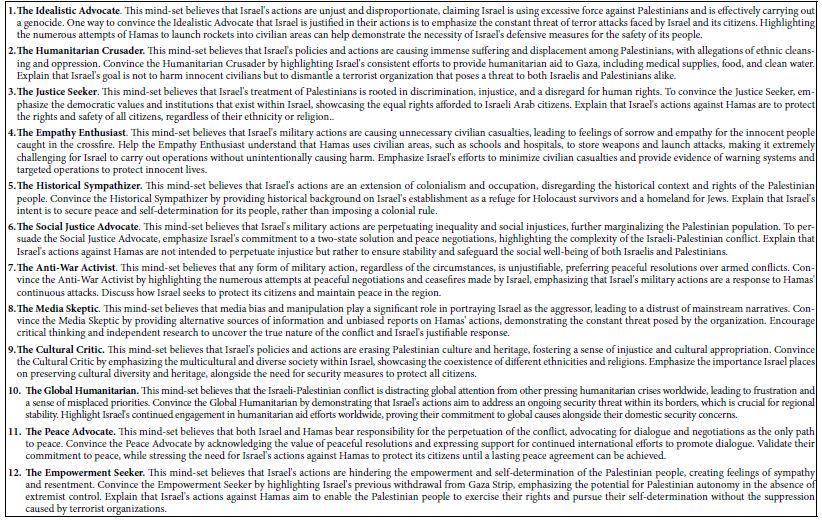

Table 4 presents the 12 mind-sets hypothesized by AI and returned to the user. The interesting points to note are that the mind-sets are plausible, seemingly different from each other, and that the AI attempted to fulfill the requests about belief regarding Israel and suggesting what to be said to justify Israel’s action. The underlying AI provides its answer in a form that is diplomatic and gentle.

Table 4: The 12 mind-sets, their hypothesized beliefs, and the suggested statements that could be used with them to convince them that Israel is doing the right thing.

AI Summarization and the Creation of ‘New Knowledge’

The creation of ‘new knowledge’ using AI has emerged as a hot topic [4-6]. The issue is whether AI produces new knowledge in the way that believe a person produces new knowledge, although the reality is this question has not really been adequately answered. What has been suggested, however, is the power of AI to drive innovation, whether that means new knowledge or simply new applications of current knowledge [7,8]. It is clear that whatever the philosophical issue may be, AI seems to be on the cusp of producing something ‘new’, something unexpected, tangible and useful [9-11] Whatever the philosophical issue may be, can the Idea Coach be said to produce something which resembles new knowledge? The results suggested by Tables 2 and 4 hint at new knowledge because the AI seems to have generated clearly delineated mind-sets which ‘make sense’, as well as mind-sets that have not been widely articulated. A further effort to produce new knowledge beyond the simple answers to requests posed to AI in Tables 1 and 3 comprises the request to AI to summarize its own contributions, viz., to take the answers that AI had previously provided, and then provide additional summarizations. Table 5 shows eight sets of ‘summarizations’ based on the limited information provided in Table 4. After the Idea Coach provided the information in Table 4, it applied a secondary set of instructions called the ‘summarizer.’ Without any interference from people, the summarizer asked eight questions shown as numbers topics in Table 4. These topics range from key ideas to themes, to interested audiences, and finally to what’s missing and to innovations.

Table 5: Eight summarizations of the key ideas presented in Table 4. The summarization is returned automatically in the ‘Idea Book’ and is provided automatically to the user.

Discussion and Conclusions

The advances in AI on the one hand, and in consumer research on the other, have been melded into a user-friend tool, known by the rubric of Mind Genomics, and available in a user-friendly platform (www.bimileap.com). What began as a tool to drive knowledge by having people evaluate combinations of messages has evolved to an AI-driven tool to generate these combinations of messages (Idea Coach). That evolution began with the effort to address the problems that novice users and perfectionists alike experience, viz., the sheer emotional difficulty of having to develop ideas. It was this emergent ‘block’ to using Mind Genomics which promoted the use of AI to suggest these ideas to the user. The results were positive, and within 18 months the use of AI was so easy that even grade-school children could become published researchers, with quite relevant topics [12]. Indeed, the experience with Idea Coach was so positive to some that it actually became fun to do. The next step was to move beyond suggesting single ideas or messages to ‘test’. Rather than requesting single ideas to be provided as answers to a question, the evolution was to provide a deeper question, to provide complete structures of knowledge, such as the request to list mind-sets for a topic, and then to define many of the properties of the mind-set. It was this breakthrough which revealed the power of AI to provide what might be called deep knowledge, or at least deep synthesis of ideas. At the practical level, the effort involved in the creation of the knowledge should be a motivator for further exploration. The entire effort to create the information presented here was less than 10 minutes. The effort involved formulating a request to AI, incorporating the request into a simple squib, and then receiving the information within 30 seconds. The Mind Genomics program, automatically storing the results and allowing ‘on-the-fly’ re-runs (iterations) of either the same request or an edited one, made it possible to explore different aspects. The final results of just two of what turned out to be dozens of easy-to-do iterations appear here. The reality is that the platform enable the exploration of many ideas having to do with the ‘genocide’ accusation, these results not shown here. Some of the other explorations involved the exploration of mind-sets in different universities (viz., Harvard, Columbia, City University of New York), as well as explorations of different types of people specified as participants (e.g., college students versus non-students, of the same age). The sheer speed with which the results emerges combined with the depth of information available immediately and in summary form suggest the opportunity to create a reference book of hundreds of pages about any topic for which the mind of people may be an important feature.

References

- Moskowitz HR, Hartmann J (2008) Consumer research: creating a solid base for innovative strategies. Trends in Food Science & Technology 19: 581-589.

- Moskowitz HR (2012) ‘Mind Genomics’: The experimental, inductive science of the ordinary, and its application to aspects of food and feeding. Physiology & Behavior 107: 606-613. [crossref]

- Radványi D, Gere A, Moskowitz HR (2020) The mind of sustainability: a mind genomics cartography. International Journal of R&D Innovation Strategy (IJRDIS) 2: 22-43.

- Cope B, Kalantzis M, Searsmith D (2021) Artificial intelligence for education: Knowledge and its assessment in AI-enabled learning ecologies. Educational Philosophy and Theory 53: 1229-1245.

- Lund BD, Wang T (2023) Chatting about ChatGPT: how may AI and GPT impact academia and libraries?. Library Hi Tech News 40: 26-29.

- Open AI. 2023 https: //beta.openai.com/docs/models/gpt-, accessed January 18, 2023

- Kaplan A, Haenlein M (2020) Rulers of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of artificial intelligence. Business Horizons 63: 37-50.

- Paschen,U, Pitt C, Kietzmann J (2020) Artificial intelligence: Building blocks and an innovation typology. Business Horizons 63: 147-155.

- Raji ID, Bender EM, Paullada A, Denton E, Hanna A et al. (2021) AI and the everything in the whole wide world benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv: 2111.15366.

- Soleimani M, Intezari A, Pauleen DJ (2022) Mitigating cognitive biases in developing AI-assisted recruitment systems: A knowledge-sharing approach. International Journal of Knowledge Management (IJKM) 18: 1-18.

- Yigitcanlar T, Cugurullo F (2020) The sustainability of artificial intelligence: An urbanistic viewpoint from the lens of smart and sustainable cities. Sustainability 12:8548

- Mendoza CL, Mendoza CI, Rappaport S, Deitel J, Moskowitz HR, et al. (2023) Empowering young people to become researchers: What do people think about the different factors involved when shopping for food? Nutrition Research & Food Science Journal 6: 1-9.