Abstract

The heritage cultural contexts of playas are poorly understood by United States federal and state agencies because there has been a persistent theory that these topographic features are marginal to Native American life. Despite this perspective, Native American peoples in formal public ethnographic interviews persistently state that these playas are old living areas going back to a time (end of the Pleistocene) when the lakes were full and surrounded by lush vegetation. Slowly the lakes receded but Indian people continued to live along their shores. Given the tens of thousands of years that Indian people have lived along the edges of these lakes, it is unsurprising that they should remember those past times and return to the playas today, seeking connection with their ancestors and the places that sustained them and permitted the formation of an ancient heritage way of life. The analysis is based on field ethnographic interviews with Paiute, Shoshone, and Goshute people.

Keywords

Pleistocene, Native American culture, Playas as Heritage, Persistent culture, Great basin ethnography, Ethnogeology

Playas as Native American Heritage Places

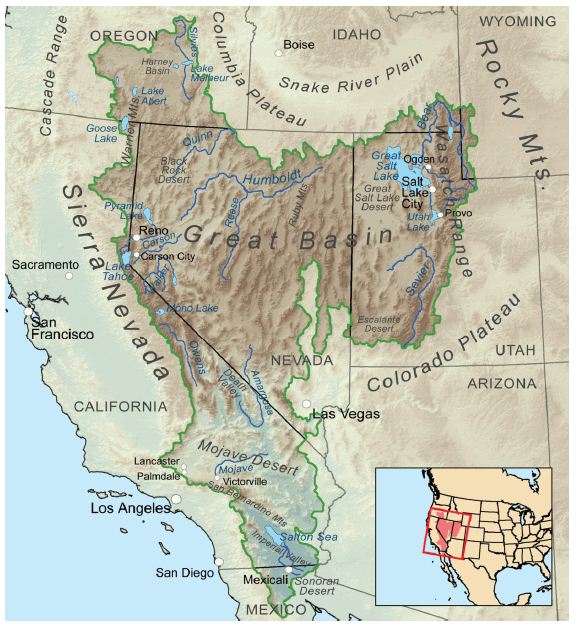

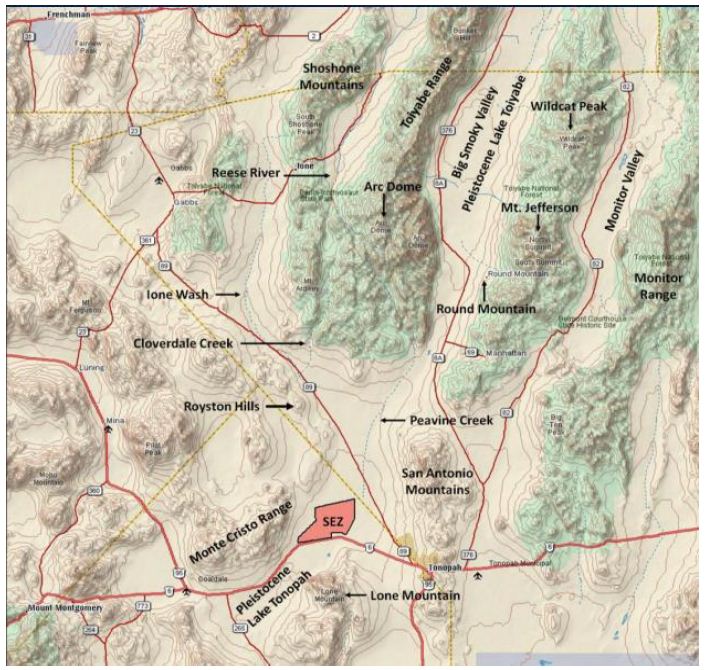

People from western cultures have regularly viewed desert playas of the western United States as sterile and of little utility except for gathering salt or minerals. In line with this unimportant valuation of desert playas by western observers, many call the region “The Great American Wasteland” [1]. The region’s culturally affiliated Native Americans, however, tend to view these playas as heritage areas extending back in deep time to the Pleistocene when they were filled with lakes, surrounded by wetlands, and drained by permanent streams. According to the University of Utah’s Shoshoni Dictionary[2] (Shoshoni Language Project 2024), the Goshute people refer to themselves as the Newe[nɨwɨ] or Newenee [nɨwɨnɨɨ] meaning the Person or the People. There have been times throughout their history where they have been referred to as Kutsipiuti (Gutsipiuti) or Kuttuhsippeh which translates to “People of the dry earth” or “People of the Desert” (literally: “dust, dry ashes People”) [1,3]. Goshute means people covered with dust, dusty people, or desert, terms which were reiterated generations later in Halmo et al. [4]. In the same study, contemporary Goshute people who are fluent in their language use the term in reference to the white alkali dust that lines the lowest portions of most valleys [4,5]. Our analysis explains why the playa dust symbolizes heritage connections with the land and past lives. Native American heritage perspectives regarding playas are required in national searches for places to drop bombs, make landing strips for large military aircraft, build industrial scale solar arrays, and mine rare earth minerals, including lithium. Native American cultural impacts regarding proposed federal land use are required by law and regulation and must be clearly articulated during environmental impact assessments. The spatial focus of this analysis is the Great Basin of the western U.S. It is largely defined by internal draining, endorheic lakes and rivers. Because of its unique topography, the Great Basin has been characterized by its state of being largely filled with water during the much wetter Pleistocene, as well as its dry salt, mineral, and sand flats in the latter Holocene. Playa is the term normally used to discuss these salty, white sand, mineral deposits (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Great Basin

The temporal frame for this heritage analysis of playas is operationally defined as the late Pleistocene, which occurred between 128,000 BP and 11,700 BP, and the Holocene, from 11,700 BP to modern times. Scientific studies have placed Native Americans in the region at least by 37,000 BP with the geoarchaeology dates of 23,000- 21,000 BP at White Sands, New Mexico [6,7] and 38,900 to 36,250 BP at the Hartley locality, a mammoth kill site situated near the Rio Puerco, New Mexico [8]. These new geoscience dates indicate that Indigenous Peoples experienced this area as both a massive wetland filled with lakes, rivers, and swamps and later as an arid desert with intermittent streams, sand dunes, small artesian springs, and heritage playas.

Pleistocene in the Great Basin

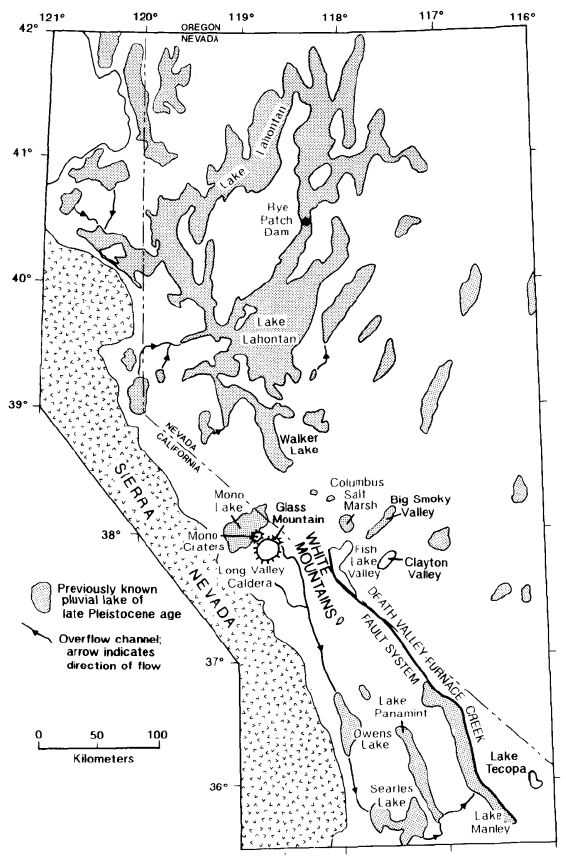

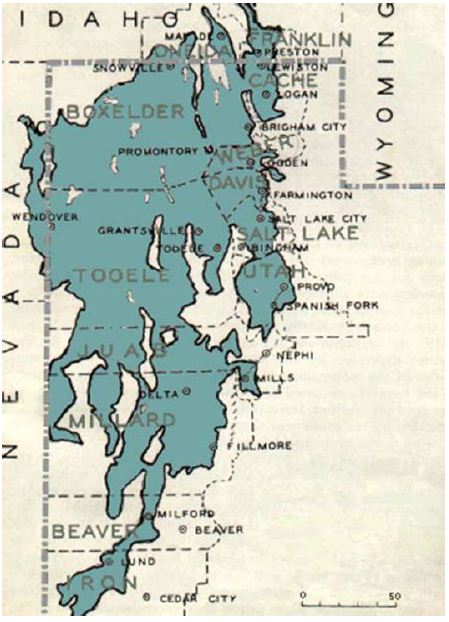

The Late Pleistocene ecology of the Great Basin and western Colorado Plateau regions was rich in fauna and flora. Central to this supportive habitat were wet forested uplands, full grasslands, and long wetlands located along a complex network of streams feeding into medium and large lakes [9]. American Indian people lived here, hunting, gathering, making trails, building communities, and engaging the topographically interesting landscape with ceremonial activities. Large mammals, like mammoth, roamed these habitats from the lowest wetlands up to 8,990 feet where the Huntington Mammoth remains were found – a subalpine environment in the late Pleistocene [9]. While contemporary scholars often focus their studies on charismatic species like mammoth, dozens of medium sized mammals were found as well including camels, horses, ground sloths, skunks, bears, sabretooth cats, American lions, flat-headed peccaries, muskoxen, mountain goats, pronghorn antelope, and American cheetahs. Many smaller mammals were also present. Like their mammal cousins, avian species were abundant and ranging in different sizes from the largest being the Incredible Teratorn with a wingspan of 17 feet and the Merriam’s Teratorn with a wingspan of 12 feet (both related to the condors and vultures) to the smallest hummingbirds [9]. Other birds included flamingos, storks, shelducks, condors, vultures, hawks, eagles, caracaras, lapwings, thick-knees, jays, cowbirds, and blackbirds. The biodiversity of the land and air was matched by the fish species and with large numbers in the streams and lakes. There were at least 20 species of fish including whitefish, cisco, trout, chum, dace, shiner, sucker, and sculpin [9]. The fish species traveled widely across the Great Basin through a variety of interconnected lakes and streams. The massive late Pleistocene Lake Bonneville was a central portion of this hydrological network supporting fish species, and by implications of great biodiversity in flora and fauna (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Pleistocene Lakes in the western Great Basin [9]

Grayson concluded his analysis with an ecological assessment of the late Pleistocene natural conditions in the Great Basin region. “The large number of species of vultures, condors, and teratorns in the Late Pleistocene Great Basin raises a number of interesting ecological questions…the fact that there were so many species of these birds here suggests that the mammal fauna of the time was not only rich in species, but also rich in number of individual animals” [9]. Paleo- Indian populations were also well supported by this bounty of nature.

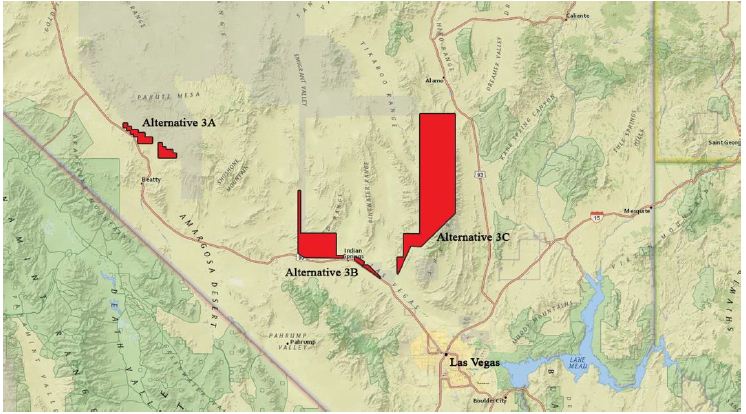

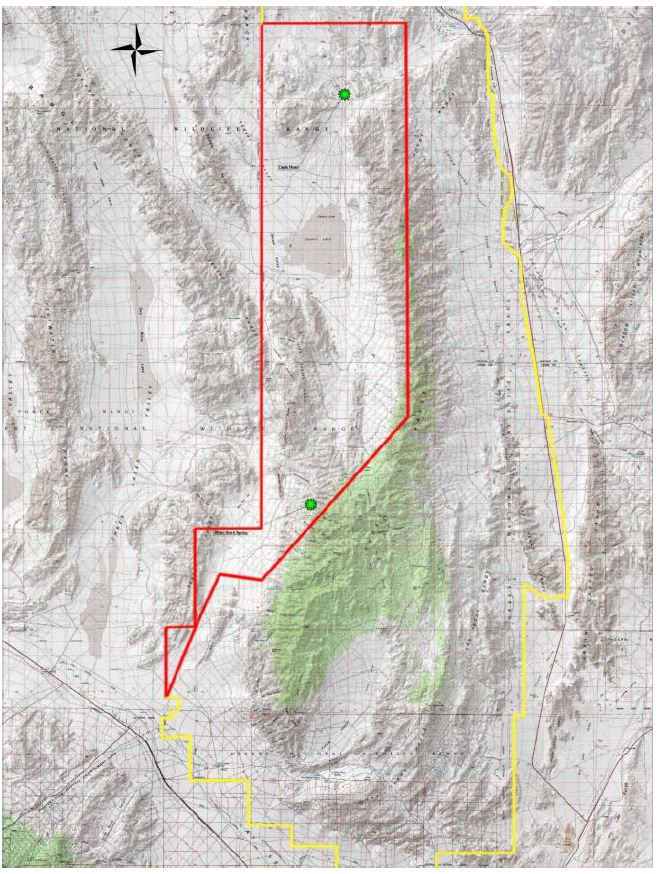

This Native American analysis of heritage playas is based on tribally approved public ethnographic findings derived from two major U.S. federal level environmental impact studies, generally referred to as either an Environmental Impact Study (EIS) or an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). Both EIAs were considered nationally important and referenced a Legislative EIS or a Programmatic EIS. The first study involves the US. Air Force and a Congressional review of a proposal to expand the Nevada Test and Training Range (NTTR) managed by the Nellis Air Force Base (Figure 3). The study involved three proposals for withdrawing lands from other federal agencies and adding them to the NTTR. Congressional review was required because the proposals involve multiple federal agencies and only the Congress has the authority to make these decisions [10]. The final report was called a Legislative EIS (LEIS).

Figure 3: Legislative EIS Proposed Withdrawn Study Areas [11]

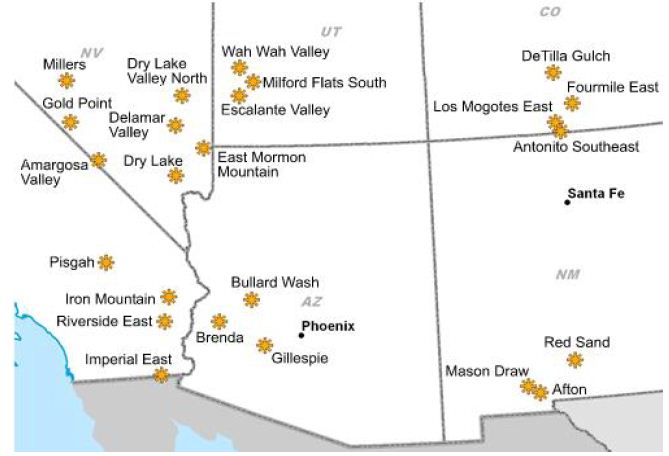

The second study involved a Solar Programmatic EIS of nine proposed large-scale energy developments centered on large playas [12]. The playas are located on lands managed by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) (Figure 4). These study areas were identified by a scientific team who suggested that establishing the social zones on playas was most effective. These areas were already managed by the federal government and the playas were largely devoted to natural and cultural resources [13]. The involved American Indian tribal governments and their appointed cultural representatives participated in the Solar PEIS to explain the meaning and cultural centrality of the plants, animals, spiritual trails, healing places, and places of historic encounters that exist in these playa lands.

Figure 4: Solar Map [12]

Both studies were funded by the involved federal agencies (U.S. Air Force and Bureau of Land Management) and conducted by a research team from the School of Anthropology at the University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ. These two large scale environmental impact assessments involved extensive and ancient playas occupied since the late Pleistocene by Native Americans. Formal government-to- government consultation with the participation of culturally affiliated Native American tribes was a foundation for each study. Each tribe selected representatives for field interviews and reviewed and approved the resulting ethnographic findings and recommendations.

Methods

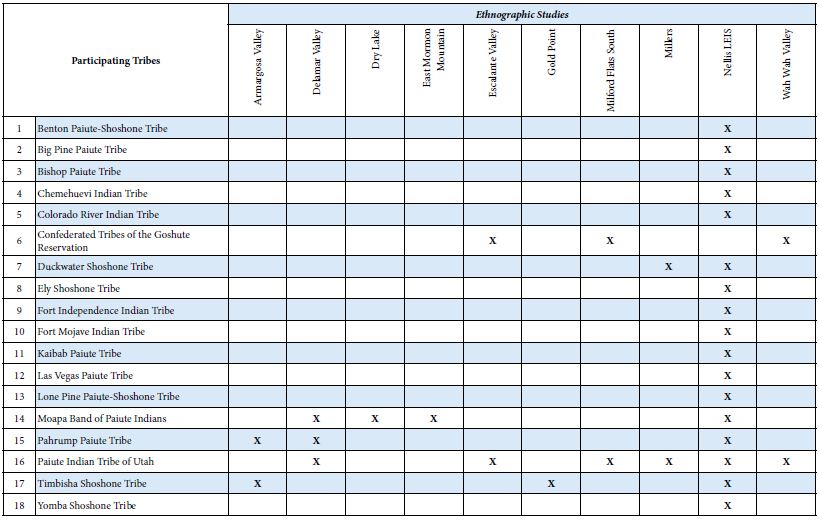

The study areas of the LEIS and Solar PEIS were defined by the management agencies, but the University of Arizona ethnographers were asked to send invitation letters for study participation to culturally affiliated tribes. Those tribes interested in participating in the study were subsequently invited to participate. Each participating tribe had experience with the UofA ethnographic study team, so the parameters of the study were both clear and understood. The UofA methods have been published elsewhere (Stoffie 2007; 2000). The study methods were developed with participating tribal elders and tribal cultural departments.The following table cross-references participating tribes and the studies involved in this analysis. The reviewed and tribally approved research findings are available at Solar PEIS [12,13] and LEIS Websites [11] (Table 1).

Table 1: Cross-Referenced Chart of Tribes to Ethongraphies

In all studies, participating tribes selected culturally knowledgeable elders to visit the study area. Elders were provided Per diem, lodging, and transportation during the fieldwork. The timing and location of the site visits were influenced by the physical condition of elders. As a rule, up to 3 hours were available at each study site and all elders were provided with a confidential interview. The report text was written by the UofA study team and then sent to elders for review, corrections, and approval. Once the elder study team approved their text, it was sent to their tribal government who checked the text to be assured it did not contain confidential cultural knowledge. In all cases, the findings were available in final public report [12].

Playas as Heritage Places

The following are research studies where ethnographic interviews have been conducted with the permission of culturally affiliated tribal governments regarding their connections to a playa. The cases have been selected because they are both comparative and contrastive, thus providing a variety of cultural perspectives on the meaning of playas. We assert that the resulting database provides a solid foundation for an ethnographic statement on Native people and heritage playas.

Desert Lake Playa

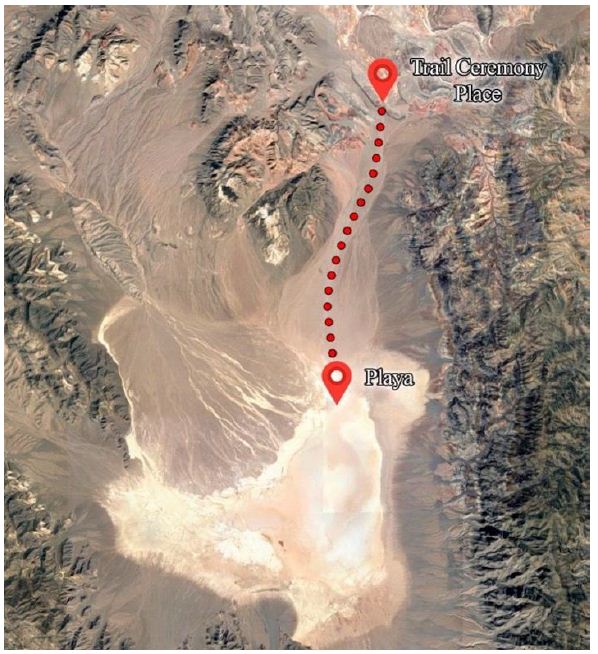

Desert Lake Playa was observed and discussed by tribal representatives during field visits as part of the LEIS (Figure 5). It was said by tribal representatives that Desert Lake is a portal through which power flows and connects to other locations, people, and living ancestors of this sacred land [14]. These larger connections of the lake include the Southern Paiutes to the south and east and Shoshones to the west and north.

Figure 5: Location of Desert Lake Playa in LEIS Area 3c Proposed Withdrawal from the Desert National Wildlife Refuge.

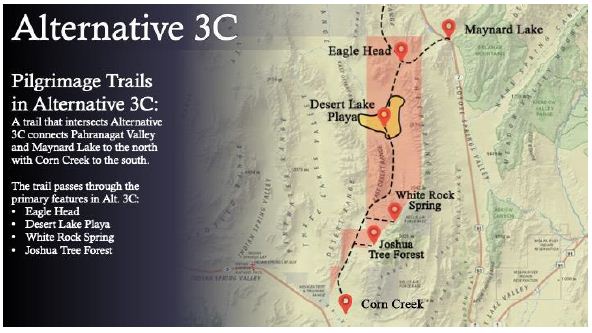

A central pilgrimage trail documented by LEIS tribal representatives passes through a topographic constriction called Eagle Head and then connects with Desert Lake Playa (Figures 6 and 7). From the playa, the trail goes to other sacred features to the north and south [14]. Nuvagantu or Mount Charleston to the south, in the Spring Mountains the primary origin mountain range for Southern Paiute peoples, and Coyote’s Jar, or Pahranagat Valley to the north, a second origin location for Pahranagat and Moapa Paiutes, indicate a significance of the area tied to the oral histories of Native American people [16]. Visiting representatives identified the playa as the destination place, while others described the trail as a connection to their origin spots.

Figure 6: Satellite Picture of the Desert Lake Playa South along the Pilgrimage Trail from Eagle Head Gap [15].

Figure 7: Places along a pilgrimage trail that both goes to and passes through Desert Lake Playa.

A proposal to improve the Alamo Road, which crosses a portion of the Desert Lake Playa, created an EIA project study area of 322 acres of archaeology inventory and three backhoe trench excavations [17]. Seven archaeological sites were recorded, two of which were recommended as eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. This archaeology study documents that the area was occupied from the Middle Archaic to the Late Ceramic periods. Further carbon dating suggests occupation dates of 6970 BP and 2000 BP. The study is important to this analysis because it documents temporally old Native presence in the wetlands that formed around Desert Lake. Ethnographic interviews concluded that Desert Lake Playa is a Culturally Sensitive Area and a Scared Site and should be nominated to the National Register of Historic Places [14] as a Traditional Cultural Property (TCP) under Criterion D: history of yielding, or potential to yield, information important in prehistory or history. The ethnographic study concluded that for a very long time, the Desert Lake Playa developed a lush environment with a plentiful water source for the fauna and flora. As the playa gradually dried, Native American people continued to visit the playa feature, leaving offerings that remain today as archaeological investigations have determined. The connection between the Desert Lake Playa and a traditional pilgrimage trail to the north and south is a critical component of this history of Native American use, as are oral histories about spiritual beings that reside in playas even after the water has gone. Not only does the playa yield information about its cultural uses, but it also holds evidence of climate fluctuations that otherwise impacted the aboriginal communities throughout the broader landscape. The playa is considered a functional and thus still active portal to other dimensions.

Big Smoky Valley

A single study is useful because it produces ethnographic findings of a people, their culture, and their environment (for more on ethnography see- Agar [18]; Mead [19]). Multiple single comparative case studies become the basis for ethnological findings (for more on ethnology see- Benedict [20]; Lowie [21]). Shoshone tribal representatives were asked to evaluate the cultural importance of resources and places in the southern end of Big Smoky Valley, Nevada [22]. Big Smoky Valley is a north-trending basin within the Basin and Range physiographic province in south-central Nevada. The valley is roughly 567,700 acres and stretches 115 miles approximately 44 miles east of the California/Nevada border, 15 miles northwest of Tonopah, Nevada. The area has been perceived as aboriginal Shoshone lands since the Pleistocene.The environmental assessment of Big Smoky Valley was one of nine study areas considered for the large-scale solar farm to be placed on playa lakes formed during the late Pleistocene [12]. Each proposal focused on a large playa. Tribal consultations and findings were reviewed and approved by tribal government. During fieldwork, tribal representatives expressed deep knowledge of the now largely dry playas, which represented a time when large lakes and wetlands filled the valleys and were the central homes of Native American peoples. Cultural continuity back to the Pleistocene was expressed in each PEIS study.

Lake Tonopah

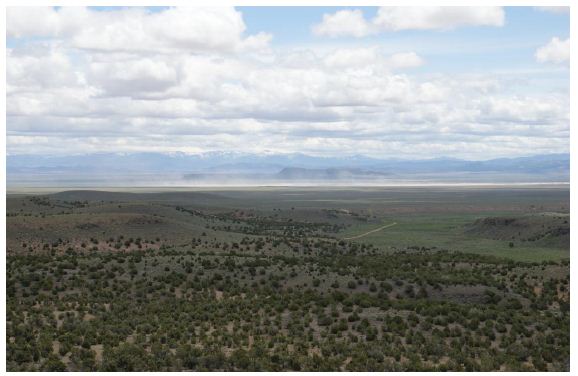

Central in the interpretation of Big Smoky Valley is a massive late Pleistocene Lake, wetland, river, and stream hydrological system dominated by what is called today ancient Lake Tonopah. This hydrological system supported both complex biodiversity and biocomplexity for tens of thousands of years—possibly since the Pleistocene as did a similar hydrological system centered on Fish Lake Valley and Columbus Marshes to the west [23] (Figure 8). According to their oral history, Indian people forever lived in this productive environment, and it became and continues to be centrally cultural in their lives.

Figure 8: The Big Smoky Valley Landscape and Pleistocene Lake Toiyabe

The watershed of ancient Lake Tonopah extends generally downhill from the north to the south along what is known today as Big Smoky Valley (Figure 8). This enclosed hydrological system is about 62 miles north to south and 21 miles east to west. Prominent mountains and ranges surround the major river, wetlands, and lakes in this watershed. Viewing this watershed anti-clockwise we find Lone Mountain in the southeast. San Antonio Mountains are in the East. Mount Jefferson and Wildcat Peak are high points in the Taquima Mountain Range, which defines the eastern edge of Big Smoky Valley. Round Mountain and Arc Dome are the southern and most visible portions of the Toiyabe Range, which is a portion of the Shoshone Mountains. Ironically the northern portion of Round Mountain is the headwater of the major north-flowing Reese River. The southeast side of Round Mountain contains Peavine Canyon, out of which flows the Peavine River. Royston Hills and Big Smoky Mountains define the watershed in the west as does the Monte Cristo Range in the southwest. Water flows off the slopes of all these mountains and hills, but Peavine River is the prominent hydrological feature today, as it flows down slope along the entire Big Smoky Valley to the current site of ancient Lake Tonopah. This hydrological system was a cultural and natural center in the lives of many Shoshone people for thousands of years.

While many individual resources and historic events were identified as significant in the Big Smoky Valley, this land was especially identified as the Origin place for the Shoshone people [22]. In ethnographic interviews, the Shoshone tribal representatives stipulated that because they have lived in these lands since the end of the Pleistocene and throughout the Holocene (or approximately 37,000 BP), they understand the dramatic shifts in climate and ecology that have occurred over these millennia.

Crescent Dune

Native American lifeways were dramatically influenced by natural shifts, but certain religious and ceremonial practices persisted unchanged. These traditional ecological understandings are carried from generation to generation through the recounting of origin stories occurring in mythic times and by strict cultural and natural resource conservation rules. At the time of the late Pleistocene, Big Smoky Valley was a wetland dominated by lakes, streams, and marshes. One Shoshone elder remembered that wetter, late Pleistocene landscape:

Just up the valley, from talking with elders and stuff, that’s where the Shoshone people started. That’s their Creation point. From there, they dispersed out into the north, south, east, and west. That’s where all the Shoshone came from, Smoky Valley, Monitor Valley. But then again, if we look at the stories, the people and the earth, they talk about a migration over water. We see that when the water skipper brought the coyote back with his little basket full of children that he made, they’re coming over water. Maybe these archaeologists have it wrong when they say that the people walked on the land. In out stories, they talk about coming over on a boat. I guess it would be a boat, if you look at the analogies. Again, we’re going back to the time when the animals talked, they conversed with each other, interacted with each other, and had ability to have children with each other. This is basically the Creation story, what I’m sharing with you. I listen to the Southern Paiute story and they talk about the Ocean Woman. You know, if you look at them, theirs is similar to ours, tied with the water. They’re the same as us. They didn’t come over walking, marching on the land like people think. They came over on the water. So we came over here in the time where this was all under water [22].

Although the climate has shifted, steams, seasonal playas and springs still dot the landscape and Shoshone use of the landscaped adapted to the drier conditions of the post-Pleistocene period. Streams originate in the mountains and at the base of the surrounding mountains and foothills, while springs provide water and luscious landscapes. Water occupies an important cultural role in the lives of Shoshone people. Natural water sources, called gwizho’naipe or life- producing water [24], play a large function in crucial rituals as well as day to day life. According to one elder:

Smoky Valley stands out. The whole valley is connected. The sand dunes and White Mountains stand out. I’m from the mountains so the mountains stand out. I was raised in the mountains so I’m a mountain person. 10,000 years ago, there was a big old lake right here where we’re sitting on [22].

In addition to the now seasonal and perennial lakes and streams, traditional Native American use of spiritual places persist. These include, for example, Crescent Dune, which is located in and around the playa with its own ecology today of pure sand and special plants. In Figure 9, Crescent Dune is viewed along with a large deposit of sand and Indian Ricegrass (Oryzopsis hymenoides), which is an ancient Native American food seen growing around Crescent Dune.

Figure 9: Crescent Dune in Big Smoky Valley

The dune rises above the valley bottom providing both a place of solitude and elevated viewscapes. Native traditional knowledge of sand dunes is extensive, and it is discussed in many of our ethnographic studies including the PEIS interviews of Big Dune on the Pleistocene Amargosa River in Nevada [25]. Dunes associated with Pleistocene lakes are understood as being a topographic feature placed at Creation for spiritual renewal and healing. According to a tribal representative, the Dunes Sing to Native people and convey information needed for ceremony. These dunes have eyes to watch over the land and a voice to share its messages in the songs that it sings and the stories it continues to tell our people ever since the beginning of time [25].

Escalante Desert

The Escalante Desert (Figure 10) is the southern portion of the extensive Pleistocene Lake Bonneville that continuously extended from Idaho to southern Utah [26]. The remains of Lake Bonneville are massive salt flats and the Great Salt Lake of northern Utah. Lake Bonneville filled its component lakes with sand, minerals, and salt which became the bottom of remnant playas like those in the Escalante Desert (Figure 11).

Figure 10: Escalante Desert with Wasatch Mountains to the east

Figure 11: Pleistocene Lake Bonneville with Southern End Filling What is Now Escalante Desert, Iron County Utah [22].

The Escalante Desert American Indian study area was traditionally occupied, used, aboriginally owned, and historically related to the Numic-speaking peoples of the Great Basin and western Colorado Plateau. This American Indian study area extends beyond the boundaries of the study area because of cultural resources in the surrounding landscape. The Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah (PITU) and the Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation (CTGR) participated in the Solar PEIS field consultations to represent the cultural interests of Numic peoples. These Numic-speaking peoples have gone on record in past projects and stipulate again here that they are the American Indian people responsible today for the cultural resources (natural and manmade) in this study area. Their ancestors were placed here by the Creator, and they have subsequently lived in these lands while maintaining and protecting these places, plants, animals, water sources, and the cultural signs of their occupation. These Numic-speaking peoples further stipulate that because they have lived in these lands since the end of the Pleistocene and throughout the Holocene, they deeply understand the dramatic shifts in climate and ecology that have occurred over these millennia. Indian lifeways were dramatically influenced by these natural shifts, but certain religious and ceremonial practices continued unchanged. These traditional ecological understandings are carried from generation to generation through the recounting of origin stories occurring in Mythic Times and by strict cultural and natural resource conservation rules. PITU and CTGR have participated in this PEIS in order to explain the meaning and cultural centrality of the plants, animals, spiritual trails, healing places, and places of historic encounters that exist in these lands.

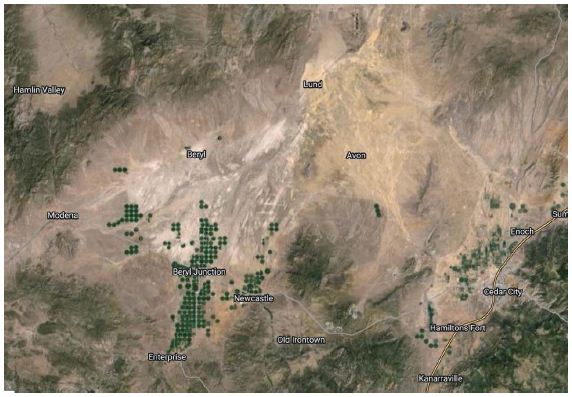

Escalante Desert (Figure 12) is named after the 1776 Spanish Fathers Escalante and Dominguez Expedition who became the first European to document the valley and the Native people living there (Figure 13). The expedition had followed well-traveled Native trails in an attempt to reach the Pacific Coast of North America. They failed, however, in this goal and turned back at the prominent hot spring in the valley. They returned via an alternative set of trails and would document the massive 1780 smallpox pandemic at Hopi on their journey to the northern New Spanish capital of Santa Fe. Because it was a government sponsored and formally approved expedition a gifted map maker was a part of the hundreds of participants.

Figure 12: The Escalante Desert, Utah is Generally Bounded by Enterprise in the South, Cedar City in the East, Lund in the North, and Modena in the West (Google Earth).

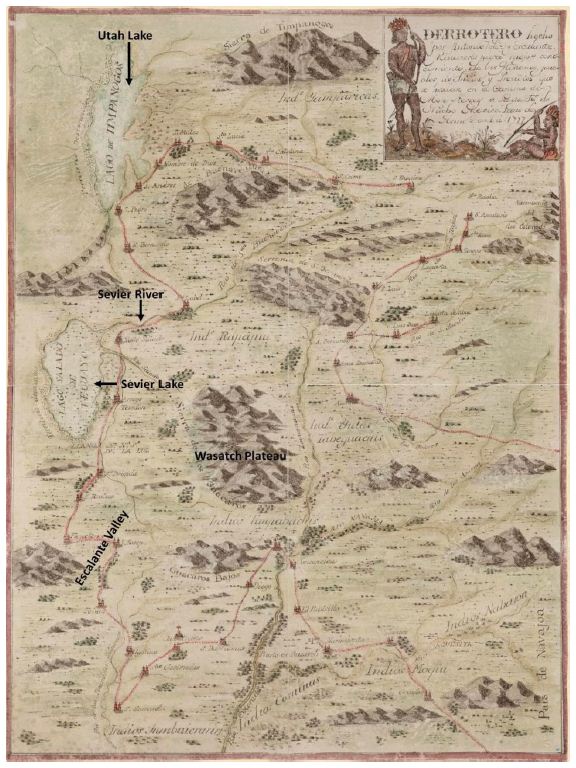

Figure 13: Escalante and Dominguez Expedition Map [22]

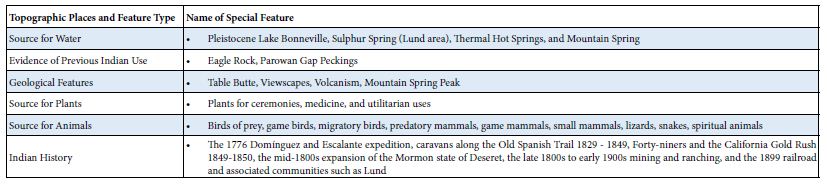

The Solar PEIS consulting tribes desired to be formally contacted on a government-to-government basis whenever projects or proposed land management actions occur on and/or near the following culturally special topographic places and features such as viewscapes, mesas from volcanic eruption, animals, and cultural plants for medicine and ceremony (Table 2). Points of contact with Euro Americans are remembered for their devastation due to diseases, armed conflicts, the arrival of grazing animals which ate Indian gardens and horticultural plants, and eventually settlement and physical removal from water and land.

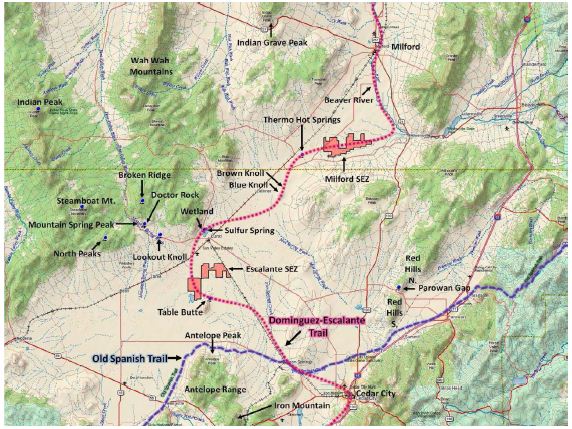

Table 2: Table of Type and Names of Culturally Significant Topographic Features and Places

A few of these cultural places and features are indicated in this map (Figure 14) that identifies their spatial relationships with each other. Their temporal relationships are hundreds of thousands of years apart. Some of these are briefly discussed in this analysis to illustrate the heritage complexity of Escalante Desert.

Figure 14: Map of Special Cultural Features Considered in This Analysis [22]

Eagle Rock Ceremonial Complex

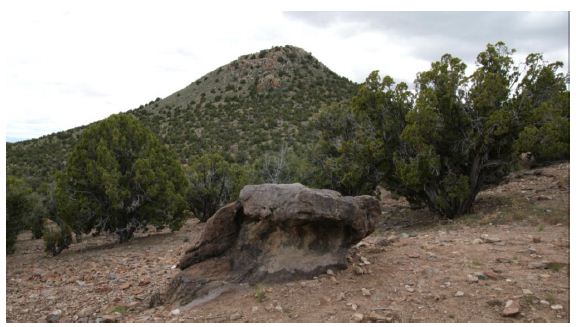

Eagle Rock is a translation of a Paiute name for an ancient healing rock. It is visually connected to the Escalante Deseret, which can be seen to the east from a landscape photo (Figure 15). The healing rock is spiritually connected though the Puha energy of the prominent mountain peak nearby, which is used for vision questing and restoring medicine songs. Next to Eagle Rock is Mountain Spring, which is used for bathing and water related plants. Nearby is Sulphur Spring, which is for purification before and after ceremony and healing.

Figure 15: Eagle Rock looking east to the Wasatch Mountains

According to an elder, Indian people came to this location from great distances to conduct important ceremonies. Eagle Rock, a famous doctor rock (Figure 16), was identified by tribal representatives as a key cultural feature in the Escalante Valley. Tribal representatives linked Eagle Rock to places such as Sulphur Springs, Mountain Spring Peak, and Mountain Spring and they thought these areas formed a large ceremonial complex. Tribal representatives described this as a traditional area used by Southern Paiute Puha’gants (shamans) and most likely Goshute shaman to tend to people who were ill and in need of rebalancing and healing. The Puha’gants would conduct complex healing ceremonies that could only be performed in a place of Puha, such as a doctor rock.

Figure 16: Eagle Rock Looking West with Mountain Spring in Background

According to an elder, rain and snow run-off from the mountains to the northwest also flow into the Escalante Valley. It is important from a Numic perspective to understand the hydrological system in this region. The flow of Puha follows the flow of water across a given landscape and connects places, people, and other elements. As water drains from the mountains in and around Eagle Rock and Mountain Spring Peak (each a place with high concentrations of Puha), the water and the Puha flow into the valley, connecting them with places like Table Butte, located to the southeast of the valley [22].

Thermo Hot Spring

These springs have been the center of activities in the immediate area since time immemorial. The hot springs are unique because they are located in the center of a valley instead of lying in a more typical location along the fault at the base of an uplifted mountain range. Thus, the Thermo Hot Springs (Figures 17 and 18) have a commanding view of the surrounding region—a 360-degree viewscape that is even further facilitated by the fact that the springs are perched above the surrounding ground by an estimated fifty feet. The views from this location include the Cricket Mountains to the north, the Mineral Mountains to the east, the Black Mountains to the south, and the San Francisco Mountains to the west. To the north is Sevier Lake and to the south is the southern expanse of the Escalante Valley. For millennia, Indian people have traveled to these special hot springs to engage in a variety of ceremonial activities. These activities include the curing of individuals using both the sulfuric muds and the mineralized hot waters. Other Indian people came to the hot spring to purify themselves before going to distant destinations where special activities such as vision quests or ceremonial balancing activities would occur. The hot springs were also visited by Puha‘gants (shamans) to acquire songs and Puha (power) needed to help their communities.

Figure 17: Grasses atop Thermo Hot Springs

Figure 18: Water from Hot Spring Mound

Water from the hot springs is used in healing ceremonies both at the springs and at other locations. Patients would come to hot springs at the instruction of or accompanied by a Puha’gant. Before entering a hot spring, Indian people would speak to the spirit of the spring, introducing themselves, and tell the spirit what type of healing was needed. Indian people have traditionally carried water from hot springs back to individuals who were unable to leave home due to age or illness [27]. Healing places occur at the locations where doctors take patients to conduct healing ceremonies or that doctors go to in order to gain insight into how to heal. Hot springs are recognized as strong sources of healing-Puha that derives from their form and characteristics, such as thermal heat or the location of the hot spring. A Puha’gant is required to facilitate the healing. Powerful minerals like paint and obsidian are used in the ceremony to assist in the healing. Hot springs are places of mixed power. Hot springs, like all water, were created for expressed and varying purposes. They can be embedded in powerful rivers, like the Pumpkin Springs in the lower Grand Canyon, canyons, like those in the Gold Strike Canyon [28], and small rivers, like those along the Virgin River near Hurricane, Utah [27]. Numic elders have stated that hot springs were also used by shamans for ritual purification prior to visiting sacred caves, valleys, or other spiritual locations, such as Parowan Gap. Such purification was necessary in order to prepare the mind and body for a safe and proper interaction with spiritual beings.

Parowan Gap

Parowan Gap (Figure 19) is a portal to the valley and the ceremonial places it contains. Before entering, prayers were made, and permission was requested. These ceremonies occurred because the valley is itself a living being with rights. This valley was a home to people. Like here and there, something attracted people to certain places where they could find medicine or food or things like that. That‘s what all these mountains and flats produced for those people. The times have changed things. Even if it‘s invisible, it changed. And the people start to change their ways without realizing or some of the times, they were forced to change. And the dances, like I said, ask for blessings for more wildlife and plants. They still have those dances [to keep the world in order]. Yeah they had round dances and certain times, like early in the morning, they’d have a sunrise ceremony. That’s when they thank the Mother Earth when the sun is coming up. They’d get a bucket of water and drink a little while they’re praying. They do that with an eagle feather usually. So a lot of Indian people are still very serious about doing those ceremonies, preserving our relationship with the earth [22].

Figure 19: Parowan Gap

Parowan Gap is one of the ceremonial places identified in the valley by Southern Paiute tribal representatives. People on pilgrimage (Puhahivats) would travel through Parowan Gap as part of the ceremonial process to and from areas out in the Escalante Valley. The gap between the volcanic ridge is a place where Puha collects, and it serves as a physical and spiritual transition zone between the Southern Paiute communities and the sacred areas out in the valley. The Parowan Gap trail follows the natural waterways and passes through the narrow and constricted opening in the Red Hills. Narrow spaces such as this contribute to the overall cultural meaning of physical and spiritual trails, especially to the Puhahivats moving along them to reach a pilgrimage destination place [29-31]. It is in these constrictions that Puha concentrates as a result of geological barriers.

A PITU Tribal Representative Explains How Parowan Gap Functioned for Puhahivats

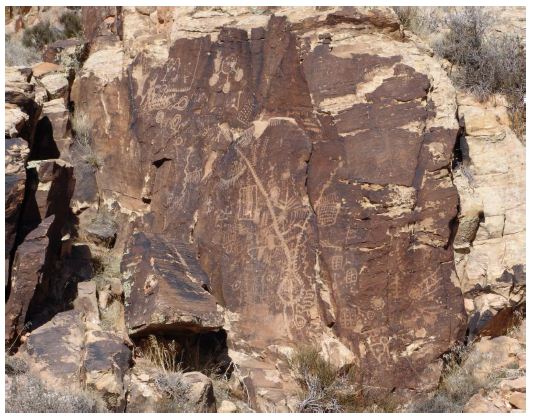

Yeah, this is a gathering place, coming through, this is a main travel route. As a destination they used to stop here; this is where they used to have the houses, right through here and on top. They used to have different places where the medicine men would pray. It‘s a long climb up there. When I was here when I was growing up, I heard that some old fellas a long time ago found some gold up there inside one of the hills up there. Apparently, way in there someplace. They found the gold up there and they took it out and took it home, then came back to get some more and couldn‘t find it. It disappeared. Someone had put the gold there [as an offering]. Yeah, in a little sack or something [22]. Parowan Gap is associated with a Southern Paiute Creation story that explains the existence of a gap in the middle of the volcanic ridge and the presence of thousands of rock peckings and rock paintings (tumpituxwinap) (Figure 20). Places with tumpituxwinap are areas used by religious specialists during ceremonial activities, because these rock peckings and paintings are believed to be derived from supernatural authorship. According to the Southern Paiute Creation Story, the rocks were once people, and they became rocks for the benefit of humanity. The images on the rocks are related to this transformation and are part of the living universe. Southern Paiute people hold strong beliefs that the rocks are alive, have Puha, and spiritual value.

Figure 20: Rock Peckings in Parowan Gap

The peckings are used by religious specialists during ceremonial activities because these rock peckings and paintings are believed to be derived from supernatural authorship. According to the Southern Paiute Creation Story, the rocks were once people, and they became rocks for the benefit of humanity. The images on the rocks are related to this transformation and are part of the living universe. Southern Paiute people hold strong beliefs that the rocks are alive and have Puha and spiritual value.

Discussion

The previous ten ethnographic studies document that playas are culturally central heritage places for participating Native American tribes. The studies also document the cultural connections between the playas, their host valley, and the surrounding mountains that have provided water to the valley bottoms since the Pleistocene. Combining the playas, the valleys where they are located, and the surrounding mountain provide a heritage assessment framework for a holistic understanding of why and how Native Americans are culturally attached to this complex landscape. These study observations are consistent despite cultural and linguistic differences between the eighteen participating tribes.

These ethnographic studies specifically document that a holistic heritage assessment centered on a large playa will typically involve the following:

- A persistent Pleistocene Lake that is the center of this heritage landscape and the source of the salts and minerals that compose the playa.

- A residual wetland surrounding the Pleistocene Lake regardless of whether it is shrinking or expanding due to climate shifts.

- An overflow river that connects places along the playa valley which connects it with other similar valleys during wetter periods but continues to serve as a traditional path for both the normal movement of people and subsequent ceremonial movement. It does this because puha tends to flow along extant and ancient waterways.

- A large singing sand dune that often existed before the end of the Pleistocene because it was derived from and even older intervals of climate change and glacial shifts.

- An origin place or mythic time portal located at a self-voiced perturbance such as a volcanic outcrop or hot spring which was defined in the valley or along its edges at Creation for the use of Native peoples.

- An abundance of animals and plants that have occurred and are missing today like Mammoths and Saber Tooth Tigers but are remember and continue to be a spiritual presence.

- An abundance of animals and plants that have become increasingly spiritual such as the horned toad as the valley becomes dryer.

A tribal representative from Pahrump and Timbisha, during the Amargosa River PEIS study [25,32] provided an understanding of the cultural meanings associated with playas and their surrounding heritage landscapes. These are paraphrased below:

Geologic resources include a range of culturally significant features such as minerals used as paint sources, salts used in curing, quartz deposits used to make tools, volcanic basalt boulders used to hold the prayers of travelers, mountain tops used for vision questing, and fossil evidence of rivers used as devices for teaching about the past. All these geologic resources are alive according to the shared epistemology of our Numic-speaking peoples. The Creator made geologic resources alive by placing Puha in them when the Earth was formed. Today the geologic resources discussed here in Amargosa River Valley all have a place in the lives and history of Indian people.

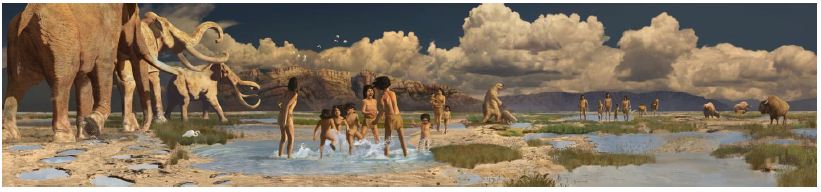

Federal agencies are beginning to recognize the presence of Native people in these Pleistocene ecosystems. This is appropriate because the scientific dating of Native people in these areas extends now to about 40,000 BP thus placing people and megafauna and massive wet ecosystems together. White Sands National Monument is such a federal response, and it has illustrated this shift in perspective with paintings of Native people and the animals and ecosystems of the heritage past (Figure 21).

Figure 21: Human & Animals Trackway, Printed with permission of Karen Carr 2024 [32]

Native Americans involved in our ethnographic studies have asserted that the image above accurately represents their oral history of these ancient times. Of importance are the heritage implications of ancient places, animals, plants, springs, and now dry lakes and rivers being celebrated by land managers museums, geoarchaeologists, and of course, the ability of new generations of Native people to be connected with their lives in Time Immemorial.

References

- Chamberlin R (1913) Place and Personal Names of the Goshute Indians of Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 52: 1-20.

- Shoshoni Language Project. Shoshoni Dictionary [Internet]. Shoshoni Dictionary. 2021 [cited 2024 May 8].

- Steward J (1943) Cultural Element Distributions: XXIII, Northern and Gosiute 3rd ed. Berkley, CA, USA: University of California Press. (Anthropological Records; vol. 8).

- Halmo D, Stoffie R, Evans M (1993) Paaitu Nanasuagaindu Pahonupi (Three Sacred Valleys): Cultural Significance of Gosiute, Paiute, and Ute Plants. Human Organization 52: 142-150.

- Stoffie R, Evans M, Halmo D (1989) Paitu Nanasuagaindu Pahonupi (Three Sacred Valleys): An Assessment of Native American Cultural Resources Potentially Affected by Proposed U.S. Air Force Electronic Combat Test Capability Actions and Alternatives at the Utah Test and Training Range. Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA: University of Michigan.

- Bennett M, Bustos D, Pigati J, Springer K, Urban T, et al. (2021) Evidence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. Science 373: 1528-1531. [crossref]

- Pigati JS, Springer KB, Honke JS, Wahl D, Champagne MR, et (2023) Independent age estimates resolve the controversy of ancient human footprints at White Sands. Science 382: 73-75. [crossref]

- Rowe T, Stafford TW, Fisher D, Enghild J, Quigg JM, et (2022) Human Occupation of the North American Colorado Plateau 37,000 Years Ago. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 10.

- Grayson D (1993) The Desert’s Past: A Natural Prehistory of the Great Basin. Washington D.C, USA: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Padrilla Estrada K (2018) Nellis Air Force Base Drops Expansion Bomb on Southern The Nevada Independent.

- Nellis Air Force NTTR Military Land Withdrawal, Legislative Environmental Impact Statement [Internet]. NTTR Military Land Withdrawal, Legislative Environmental Impact Statement.

- Solar PEIS (2022) Ethnographic Analyses for Nine Proposed SEZs. Social Energy Development Programmatic EIS Information Center [Internet]. Ethnographic Analyses for Nine Proposed SEZs. Social Energy Development Programmatic EIS Information Center.

- Argonne National Lab (2024) Utility-Scale Solar Programmatic Bureau of Land Management. Argonne [Internet]. Utility-Scale Solar Programmatic EIS. Bureau of Land Management. Argonne.

- Stoffie R (2018) Nellis LEIS: Native American Ethnographic Study. In Las Vegas, NV, USA.

- Stoffie R, Arnold R, Van Vlack K (2022) Landscape Is Alive: Nuwuvi Pilgrimage and Power Places in Nevada. Land 11.

- Stoffie R, Toupal R, Zedeño M, Patrick B (2002) East of Nellis: Cultural Landscapes of the Sheep and Pahranagat Mountain Ranges, An Ethnographic Assessment of American Indian Places and Resources in the Desert National Wildlife Range and the Pahranagat National Wildlife Refuge of Nevada. Tucson, AZ, USA: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona.

- Wriston T, Gilreath A, Duke D (2007) Desert Dry Lake Archaeological and Geomorphological Survey, North of Las Vegas, Nevada. Davis, CA, USA: Far Western Anthropological Research Group.

- Agar M (1996) The Professional Stranger: An Informal Introduction to Leeds, England: Emerald Publishing.

- Mead M (1928) Coming of Age in Samoa: A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western New York, NY, USA: William Morrow and Co.

- Benedict R (1946) The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Boston, MA: Houghton Miffiin.

- Lowie R (1937) The History of Ethnological Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- Stoffie, R, Van Vlack K, Johnson H, Dukes P, De Sola S, et (2011) Tribally Approved American Indian Ethnographic Analysis of the Proposed Escalante Solar Energy Zone [Internet]. Tucson, AZ, USA: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona.

- Reheis MC, Caskey J, Bright J, Paces JB, Mahan S, et (2019) Pleistocene lakes and paleohydrologic environments of the Tecopa basin, California: Constraints on the drainage integration of the Amargosa River. GSA Bulletin 132: 1537-1565.

- Gould D, Glowacka M (2004) Nagotooh (Gahni): The Bonding between Mother and Child in Shoshoni Tradition. Ethnology 43: 185-191.

- Stoffie R, Van Vlack K, Johnson H, Dukes P, De Sola S, et al. (2011) Tribally Approved American Indian Ethnographic Analysis of the Proposed Amargosa Valley Solar Energy Zone [Internet]. Tucson, AZ, USA: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona.

- Laabs B, Munroe J (2016) THE RELATIVE TIMING OF LATE PLEISTOCENE GLACIER AND PLUVIAL LAKE MAXIMA IN THE NORTHERN GREAT BASIN, NEVADA AND UTAH, U.S.A.

- Stoffie RW, Austin DE, Fulfrost BK, Phillips III AM, Drye TF (1995) Itus, Auv, Te’ek (Past, Present, Future) [Internet]. Bureau of Applied Anthropology, University of Arizona.

- Stoffie R, Zedeño M, Eisenberg A, Toupal R, Carroll A, et (2000) (The Backbone of the River): American Indian Ethnographic Studies Regarding the Hoover Dam Bypass Project. Tucson, AZ, USA: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona.

- Van Vlack K (2012) Southern Paiute Pilgrimage and Relationship Formation. Journal of Ethnology 51: 129-140.

- Van Vlack K (2012) Puaxant Tuvip: Powerlands Southern Paiute Cultural Landscapes and Pilgrimage Trails, [PhD Dissertation]. [Tucson, AZ]: University of Arizona.

- Van Vlack K (2018) Puha Po to Kavaicuwac: A Southern Paiute Pilgrimage in Southern International Journal of Intangible Heritage 13: 129-141.

- Carr K (2024.) Humans and Animals Trackway, White Sands National Monument.