DOI: 10.31038/IDT.2021214

Abstract

A sudden yet very small outbreak of COVID-19 mystery community transmissions occurred in a defined arc across the inner Western and outer Northern suburbs of Melbourne in May-June 2021. An infection zone that could be 1000 km2 in size. These sudden outbreaks of genuine mystery cases could not be traced to any direct infected contacts nor could they be directly genomically linked to any known infection clusters (e.g. among infected international travellers in hotel quarantine). In response the Government of Victoria on the recommendation of the Chief Medical Officer and the Victorian Department of Health locked down the entire State of Victoria in an extreme Stage 4 emergency. As a consequence, large numbers of PCR COVID-19 tests on oro-nasal swabs were conducted (> 30, 000 per day at peak) and all positives quarantined at home, a directive enforced by police and in some cases the Australian Army. Citizens were neither allowed to leave Melbourne nor from Victoria to any other State of Australia. Contact tracing was conducted on a very large scale by teams of experienced tracers. Several sudden mystery outbreaks continued to occur despite the lock-down on people movements. This included restriction of numbers of visitors at homes, crowd-size limitations, curtailment of sporting events, school closures, mandatory mask wearing, and personal tracking of all individuals in shops and supermarkets (via a personal “QR” digital tracking system linked to mobile phones or via written personal contact statements at store or shop entry). Many of the COVID-19 variants of concern (PANGO classification) were clearly mature human-passaged virions, many of which have been identified in the current and very large 2nd Wave Indian epidemic. We show here there is plausible strong evidence that a heterogeneous set of these “Indian” variants may have been transported by prevailing tropospheric global wind systems via the Indian Ocean and Southern Ocean (Roaring Forties West to East on the 40o S Latitude line) to Victoria, Australia. There is much precedent for such global wind transportations in the history of past Influenza virus pandemics in the last 100 years and the present observations relating to COVID-19 events in Australia are discussed in that context.

Introduction

A cool and objective scientific understanding the origins and global spread of the COVID-19 virus is the most pressing issue of our time. The multifactorial evidence that we have assembled through 2020 is fully consistent with COVID-19 arriving first via a loosely-held life-bearing carbonaceous cometary bolide that dispersed its viral cargo in the stratosphere on the 40o N Latitude line over Jilin in North East China on the night of October 11 2019 [1-3]. A long series of air-sampling experiments carried out in the stratosphere over the past 20 years have revealed unequivocal evidence of biological entities ranging in size from tens of nanometres, identifiable as virions, to several microns corresponding to bacteria at heights of up to 41 km [4,5]. More recently, Grebennikova et al. have identified by PCR techniques several bacterial species on the outside of the International Space Station (orbiting at a height of 400km) which are most plausibly of cometary origin [6]. A variable population of bacteria and viruses in the stratosphere thus appears to have a firm empirical basis, and is moreover consistent with the theory of cometary panspermia for which there is now a formidable body of evidence [7,8].

A critical evaluation of all the relevant evidence suggests the causative virus of the COVID-19 pandemic could not have come from an infected bat or pangolin to infect all of the central region of China around Wuhan city and Hubei province on the scale that was witnessed in Nov 2019-Jan 2020 [2,9]. In our opinion, guided by the relevant evidence and observations of many similar instances of suddenly emergent pandemics throughout history [10], this pandemic is entirely natural which is by no means unique. It represents a natural phenomenon consistent with the emerging paradigm that life is an all pervasive cosmic phenomenon [10-12]. It is unrelated to putative explanations based on non-scientific ad hoc human-induced conspiracy theories – such as those currently in vogue in the popular press e.g. “Wuhan Virus Lab Leak” theories. It cannot be emphasised too strongly that all such explanations are non-scientific. They require too many ad hoc assumptions, many incoherent and contradictory, when rationally examined in the light of all the unfolding temporal key evidence. The appropriate scientific domains in which the relevant data must be addressed and analysed for this pandemic must of necessity include immunology, genetics, epidemiology, astrobiology and atmospheric physics. The group of scientists that we represent has been tracking, analysing, explaining as well as predicting with accuracy the course of this suddenly emergent virus disease from its origin and early spread in Wuhan in late November 2019 through January 2020, following in our view the arrival at the Earth of a putative life-bearing cometary bolide [1,3]. We then analysed the early evidence against the standard explanation of global infection-driven solely by person-to-person (P-to-P) transfer of the COVID-19 virus [13]. The long-distance transfer of infection after the initial Wuhan strike to other far-flung global regions occurred primarily not by P-to-P transfer but via upper level tropospheric/stratospheric jet streams on a 40o – 60o N latitude band from East to West [14]. This process combined with more localised lower-level tropospheric wind systems (West-to-East) explains much of the unfolding data in the early weeks of the pandemic. This includes the otherwise mysterious transport across the Pacific Ocean of the L haplotype of the Wuhan-plumed P-to-P virus to infect the Grand Princess cruise ship off San Francisco [3].

The pandemic next appeared to move into lower – level Atlantic Ocean prevailing wind systems and thence into the Southern Hemisphere [15]. During this early period, up to May 2020, many ships at sea became engaged with sudden and seemingly mysterious COVID-19 outbreaks: cruise ships (Diamond Princess, Westerdam Grand Princess), aircraft carriers (USS Theodore Roosevelt, the French Navy’s Charles de Gaulle), various fishing trawlers and live animal transportation ships [9,16]. Wherever these ‘ship at sea’ strikes could be cleanly analysed it became evident that all such outbreaks are best understood as mid-ocean depositions of COVID-19 virions with all the tell-tale signs of aerial pathogenic attack [9,16]. Moreover, sudden strikes on isolated islands such as Sri Lanka that had flat-lined in COVID-19 case incidence all year (2020) and then suddenly became engaged in a few days (Oct 4-6, 2020) with over a thousand active cases are difficult to understand in terms of traditional P-to-P spreads considering the associated minimum incubation time between transfers of infections of about one week [3,17]. Another remarkable incident of a similar kind is the isolated Chilean military base in Antartica, thousands of kilometres from civilisation that became suddenly engaged late December 2020 [3]. A cool objective assessment of all these types of striking sudden COVID-19 outbreaks are inconsistent with traditional P-to-P infectious disease epidemiology, but entirely consistent with transportation via tropospheric winds and precipitation (rain) bringing the viral-laden clouds to ground. In this way we can explain the sudden and simultaneous appearance of sporadic mass infections in widely separated geographical locations that are mutually isolated, and thus cannot be cross-infecting one another by a P-to-P spread process. The intensity of each outbreak in any given geographical zone depends only upon viral density at in-fall, and the exposed susceptible human population density in that area. The viral density detected at ground level is predicted to be quite patchy, on scales determined by the turbulence patterns caused by thermal fluctuations determined by local heat sources.

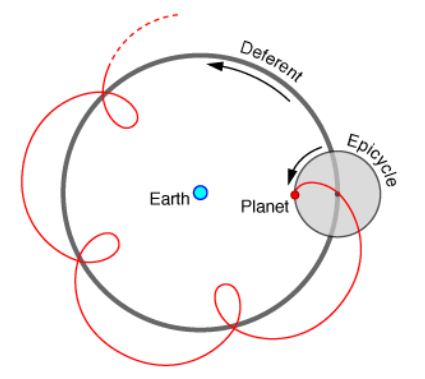

The modern tendency to invoke the ad hoc concepts of super spreaders, asymptomatic carriers or “stranger-to-stranger” spread to explain any baffling aspects of the pandemic is a desperate attempt to maintain the status quo of the terrestrial origin of the virus and its P-to-P spread. It is interesting to recall that this is strikingly reminiscent of the Ptolemaic epicycles that were invoked in the last days of the Copernican revolution (Supplementary Information). It was the multiplication of such epicycles that finally led to the rejection of the Ptolemaic Earth-centred universe. Whether we have now come anywhere near this critical point in the story of COVID-19 epidemiology is left to be seen. Through 2020 we analysed the genetics of adaption of the COVID-19 virus in the first few months of the pandemic in 2020 at clear explosive hotspot locations (Wuhan, New York City, US West Coast) and defined the initial (ab initio) haplotype sorting process used by all respiratory epithelial lining cells in the innate -immune driven host -parasite relationship in the first 24-48 hrs of infection – APOBEC and ADAR deaminase-driven ribo-switching of a common set of COVID-19 haplotypes. These are best understood as co-ordinated single nucleotide variant (SNV) changes consistent with successful effective replicative RNA secondary structures [9,18]. This is discussed further in ‘Haplotype Analysis’ in Materials and Methods.

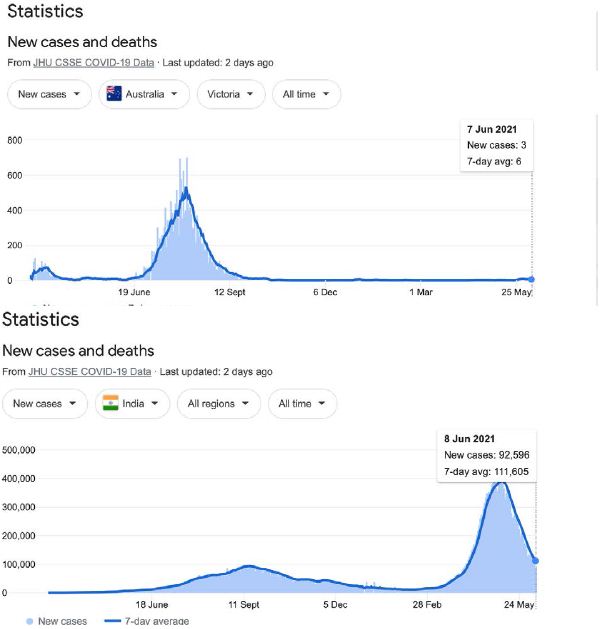

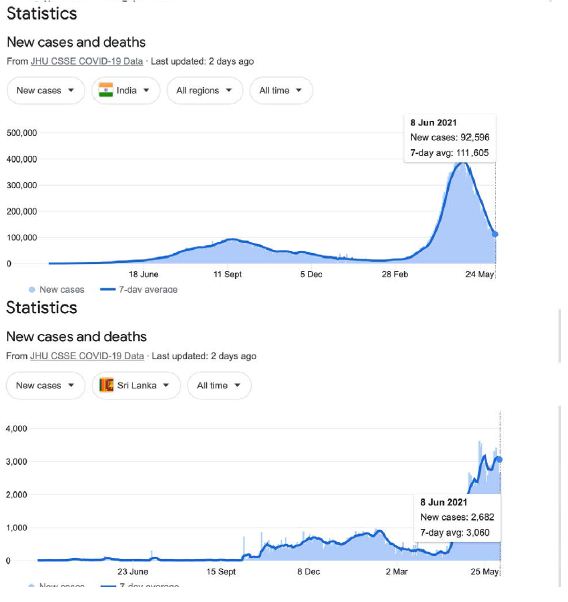

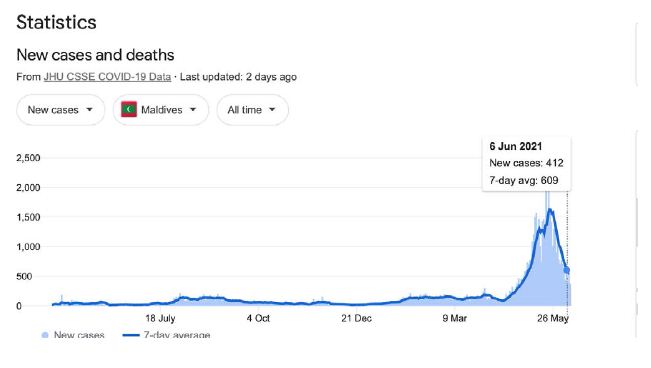

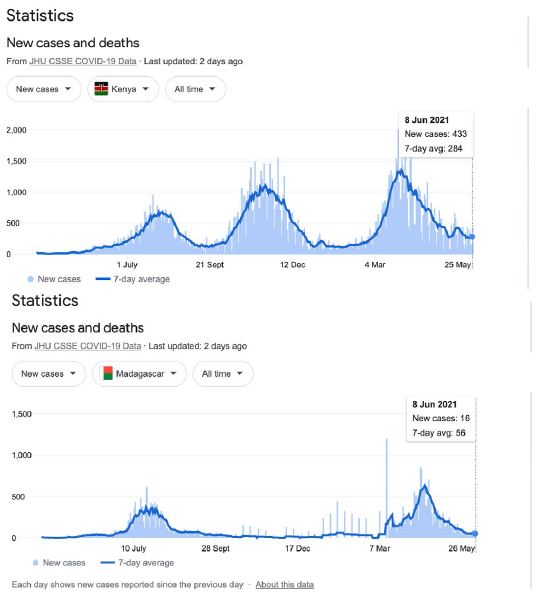

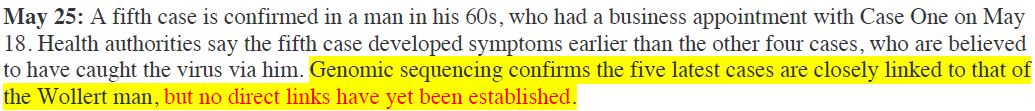

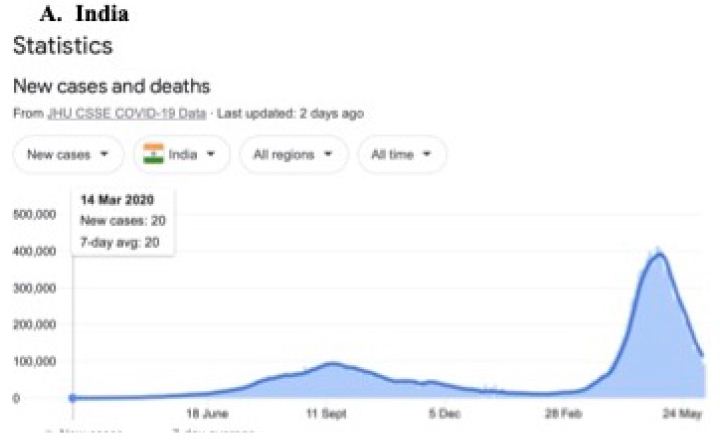

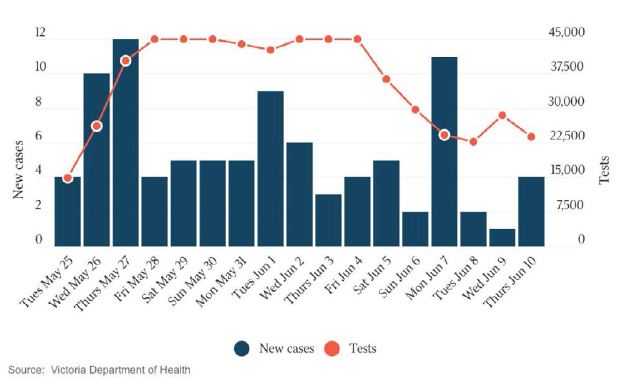

In a review of all the relevant key evidence the most parsimonious explanation seems to be that COVID-19 came from space [2,3], just as have many other similar suddenly emergent pandemics past and recent: such as the Spanish Flu 1918-1919 and the other pandemics that punctuate history over millennia, and in particular over the best documented period over the past 100 years spanning the 20th and 21st centuries [10-12]. In this report we now critically evaluate the publicly available infection and COVID-19 genomic data for the sudden, yet small, outbreak of COVID-19 cases in Victoria, Australia in May – June 2021. Many of the initiating cases prior to P-to-P spreading within a local cluster are genuine mystery/community transmissions that have still not been resolved as this paper was submitted (as June 19 2021) – either by contact tracing or by genomic sequencing matching with already known clusters in the epidemic target zone. Given the global isolation of Australia as an island continent, and the further isolation of the State of Victoria, taken together with the stringent quarantine and isolation regulations combined with diligent contact tracing that have been in place, we have here a remarkable setting for a controlled experiment for testing transmission models of the COVID-19 pandemic. As seen in Figure 1 all the case numbers in Australia are minuscule in comparison with the Northern Hemisphere infected zones (and see Supplementary Information). Further advantages in the situation in Victoria include the scale of mass PCR COVID-19 testing (≥30,000 per day, Figure 2); and a strictly policed social distancing/mask covering with Stage 3 and Stage 4 lock down regulations enforced in Victoria with the deployment of police and sometimes the army. The available data in the public domain allows scientific conclusions not as easily derived for the Northern Hemisphere infected zones, where the disease is of far greater intensity and wider geographic extent (two to four orders of magnitude greater than the greater metropolitan area of Melbourne, Victoria – this has, however, had well over 90% of all COVID-19 cases in Australia in 2020 and 2021 c.f. Figure 1 and URL link).

Figure 1: Magnitude and timing of the COVID-19 epidemics in Inda, United Kingdom amd Australia during 2020 and 2021.

Google: “Coronavirus disease statistics”URL is https://tinyurl.com/hcp8axvn. This gives you the “Australia” dashboard (from there you can choose your country in the menu bar scroll).

Figure 2: New Cases per Day and Total PCR Tests per Day in Victoria. The Australian 10 June 2021. Hard Stage 4 lockdown across entire state of Victoria introduced on May 27.

There are two general tropospheric viral-laden in-fall hypotheses that could serve to explain the patterns in these mystery infection data. They could operate together, or one or other may prevail in quantitative terms.

The two possibilities are:

A. The sudden outbreaks are due to precipitation bringing down virus-laden cometary dust in an arc around inner-outer Melbourne (West-North, approximately 1000 Km2) thus contaminating the environment and causing spot mystery infections of SARS-CoV-2 respiratory disease (generating simple haplotype variants ab initio, as Steele and Lindley [18]).

B. The sudden outbreaks are caused by the same precipitation (rain) bringing down human passaged virions transported in global wind circulation from Northern Hemisphere infected zones, in particular from the Indian outbreaks.

The most likely source, in our view, would be the putative and massive viral plume over India of virions which have already “gone through” human passage (P-to-P), and thus showing substantially modified genomic sequences as multiple P-to-P products from the early ab initio haplotype sequences These were discussed, using data from the first three months of 2020, for haplotype diversification between Wuhan and New York City [9,18].

Here we assemble the evidence that strongly supports hypothesis B, that all the community transmission ‘mystery cases’ in the Victorian epidemic in May – June 2020 may have been caused by a range of Indian human-passaged viruses delivered to Victoria, Australia, from elsewhere, most likely via the Indian subcontinent viral plume via tropospheric wind systems. This conclusion is not inconsistent with low level tropospheric prevailing wind systems spreading viral pandemics in the recent past via non P-to-P processes on scale [10]. Many striking non P-to-P spreading events like this were reviewed over 30 years ago by Hammond et al. [19].

Materials and Methods

Publicly Available Data Resources

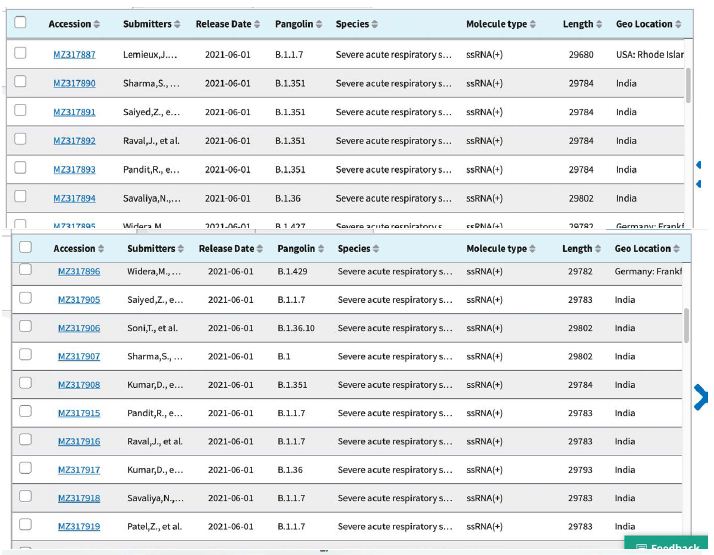

a. GenBank/NCBI Virus db

For full length COVID-19 genomic sequences and their haplotype analysis against the Wuhan Hu-1 29903 nt long RNA reference sequence (NC_045512.2) all Genbank Accession sequence data were obtained and aligned (multiple sequence alignments) using the NCBI Virus database and alignment tools. This publicly accessible site is hosted at The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, Maryland, USA, which curates SARS-CoV-2 sequences at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sars-cov-2/#nucleotide-sequences

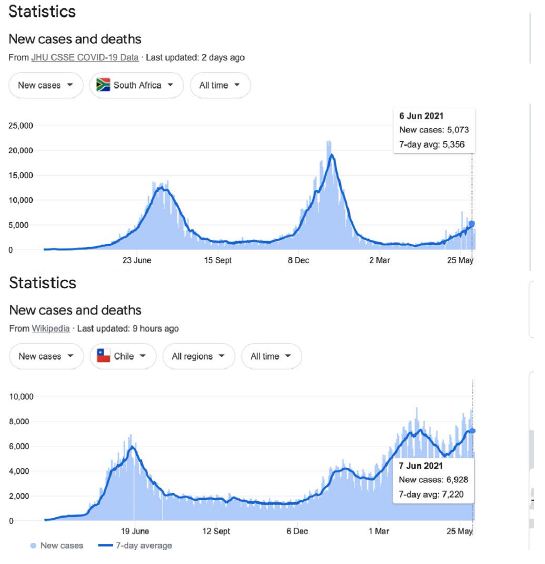

b. Epidemiological Information

This is from that published daily by the national newspaper The Australian and other information from Melbourne’s Herald-Sun newspaper. All specific details are referenced or expanded on in the Supplementary Information. Other data for background long term cross checking can be access at The Victorian Department of Health website https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/victorian-coronavirus-covid-19-data

c. Weather Information

This was from The Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) and also news reports through April and May 2021

http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/dwo/202105/html/IDCJDW3050.202105.shtml

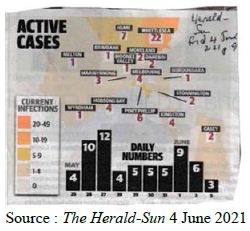

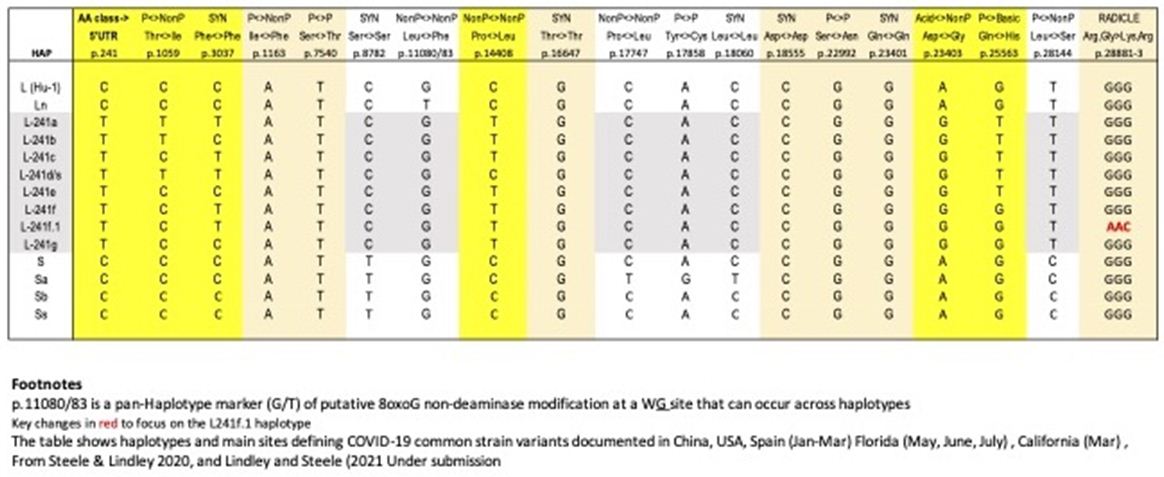

Haplotype Analysis

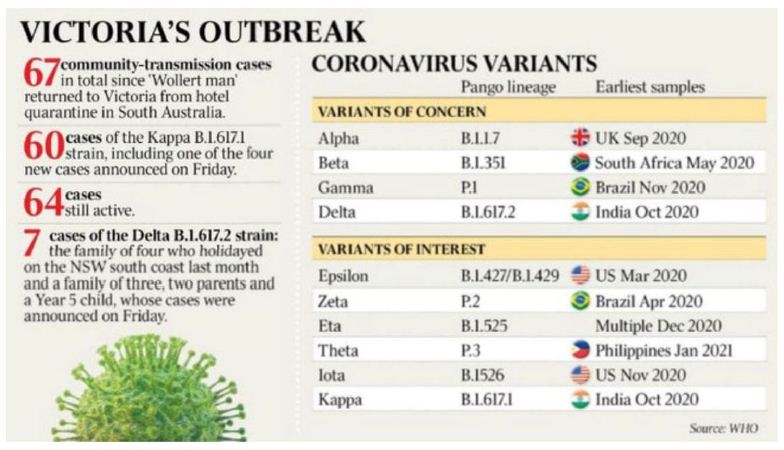

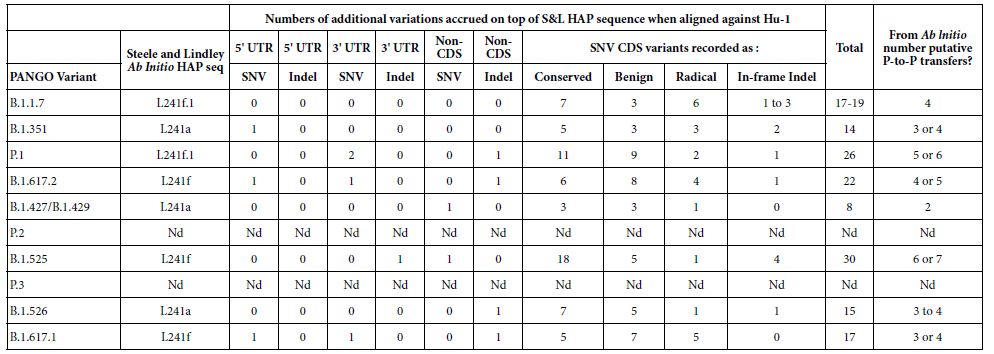

The haplotype approach to COVID-19 sequence diversification [18] differs from the PANGO classification system which uses a phylogenetic approach which generates putative person-to-person (P-to-P) lineages, clusters and clades [20,21]. The ab initio haplotype-sort/selection explanation, during first infection of respiratory epithelial cells in the first Host-Parasite encounter – by viral-laden meteorite tropospheric dust – is a better primary explanation of the APOBEC/ADAR-driven deaminase ribo-switching process and informs classification of sequences through molecular understanding based on variant RNA secondary structures. In the first three months of the pandemic this ribo-switching haplotype sorting and quasi-species selection process operates in the first subject infected host [22,23]. This generates, in our view, a range of quasi-species and then host-parasite selection allows successful emergence of a replicative 29903 nt long RNA secondary structure haplotype in that subject host (Steele and Lindley 2020 [18] Table 1). The PANGO variants published in The Australian newspaper (Saturday 5 June 2021) which are of concern to the Victorian Department of Health (Figure 3) have been assigned haplotypes using these markers (Table 2).

Table 1: Putative Ab Initio Haplotypes and Main Sites Defining COVID-19 Common Strain Variants in first 3 months of the pandemic (Jan-Mar 2020).

Figure 3: The Australian Saturday 5 June 2021

Table 2: PANGO variants of COVID-19 of interest and concern in Melbourne, Victoria outbreak of mystery cases in May-June 2021.

The PANGO variants from The Weekend Australian June 5-6 2021.

Criteria for a SNV in the Coding Regions (CDS) Classed as Conserved, Benign, Radical (Table 2) – as defined in Steele and Lindley (2020) [18]

Conserved: These are synonymous SNVs or a SNV change leading to the same amino acid (AA) functional class. Benign: These are AA changes which are Polar<-> NonPolar, Acid <-> Polar, or Basic<-> Polar. Radicle: These are AA changes Acid<-> NonPolar, Basic<-> NonPolar, Acidic<-> Basic.

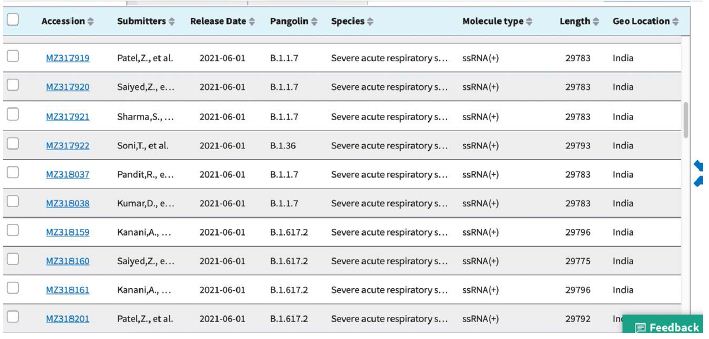

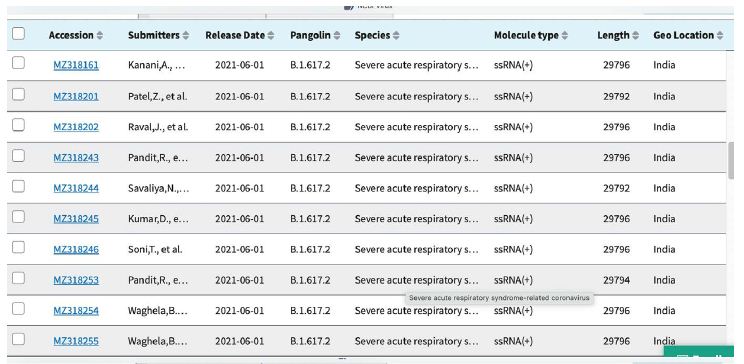

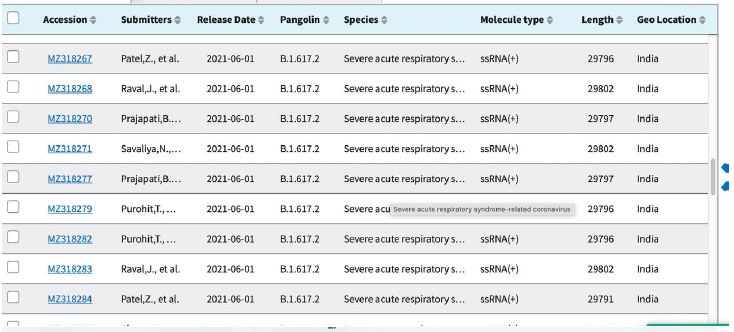

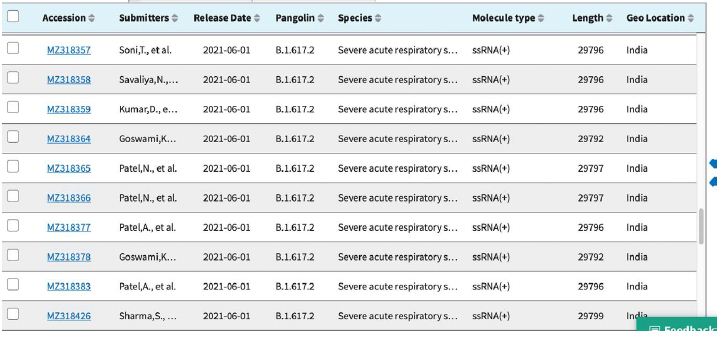

Multiple PANGO Sequences Used to Determine Haplotypes as Shown in Table 2

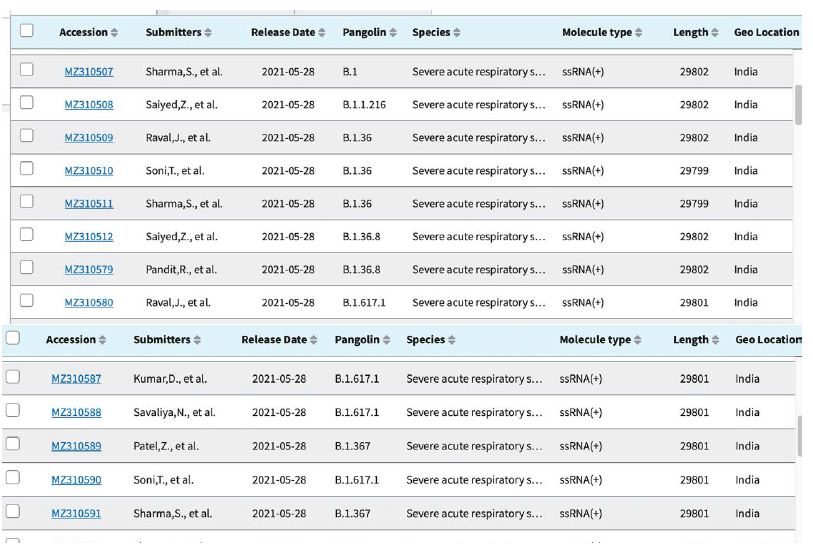

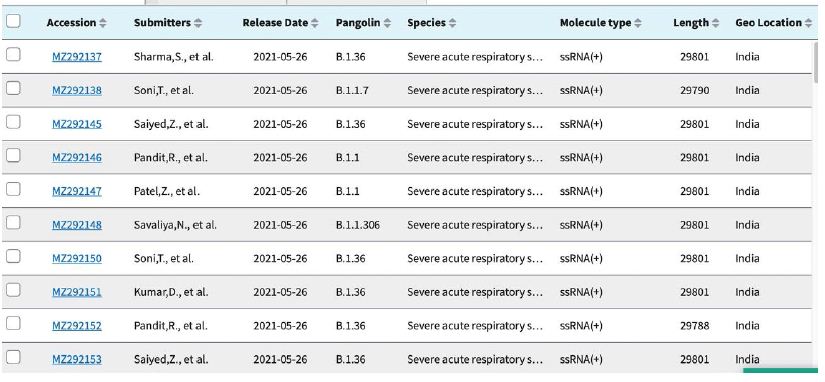

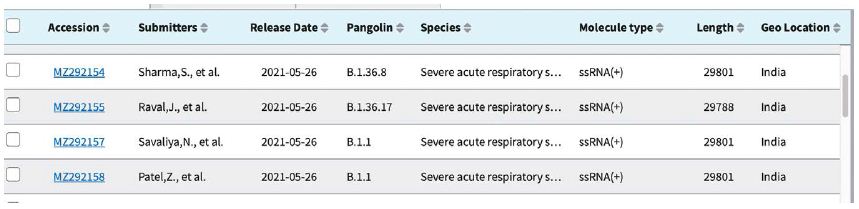

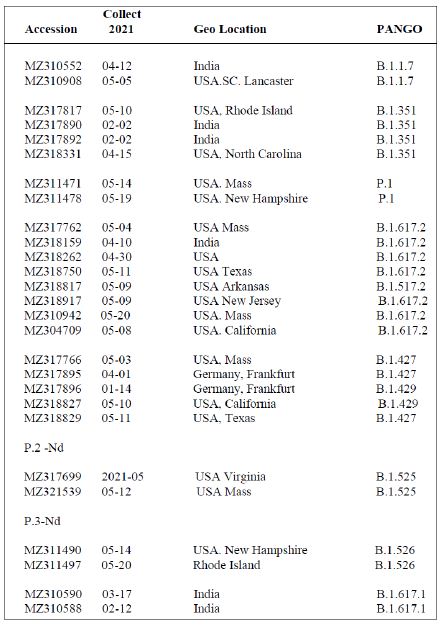

Shown in Table 3 are the GenBank accession numbers of many of the PANGO variants of concern in Victoria from the NCBI Virus website for the haplotype analysis in the Melbourne, Victoria outbreak of mystery cases in May-June 2021- all haplotyped in multiple alignments v Hu-1 (NC_045512).

Table 3: Gen Bank accession numbers of all PANGO sequences multiply aligned for haplotype assignment.

Among a Set of the Same “PANGO Designated Variants” There Will be Variable Sites – that is “Not All PANGOS are Identical”

It is important to understand that when newly isolated COVID-19 genomic sequences are assigned a PANGO variant/lineage label, all PANGO variants with that label are not necessarily identical. Human passaged (P-to-P) will introduce further new variable sites within that haplotypic framework. For example in a multiple alignment against the Hu-1 reference of six B.1.617.2 variants (MZ318750, MZ318917, MZ320553, MZ317762, MZ318262, MZ318150) the number of non- haplotypic shared sites above the 22 listed in Table 2 for B.1.617.2, there are 49 other sites that can vary. A similar pattern like this applies to sets of the other PANGO haplotypes in Table 2 aligned against Hu-1. Thus the statement that a freshly isolated sequence “has a particular PANGO variant sequence (i.e. haplotype) should not be taken to mean all members of that variant are identical as APOBEC/ADAR-driven variation at P-to-P transfers ensures most will be not identical. Most of these differences (>95%) result in conserved or benign AA changes i.e. there is considerable sequence conservation at the protein level due to Darwinian purifying selection (e.g. in the six B.1.617.2 sequences discussed above 48 of the 49 variable sites are conserved or benign as defined).

Estimates of P-to-P Transfers (Table 2)

It should be noted here that the estimates of the numbers of putative P-to-P transfers since ab initio creation in the first infection from raw meteorite dust-derived virus, is based on conservative estimates from the observations in the Wuhan (Jan 2020) and New York City (Mar 2020) hotspot zones [18].

Results and Discussion

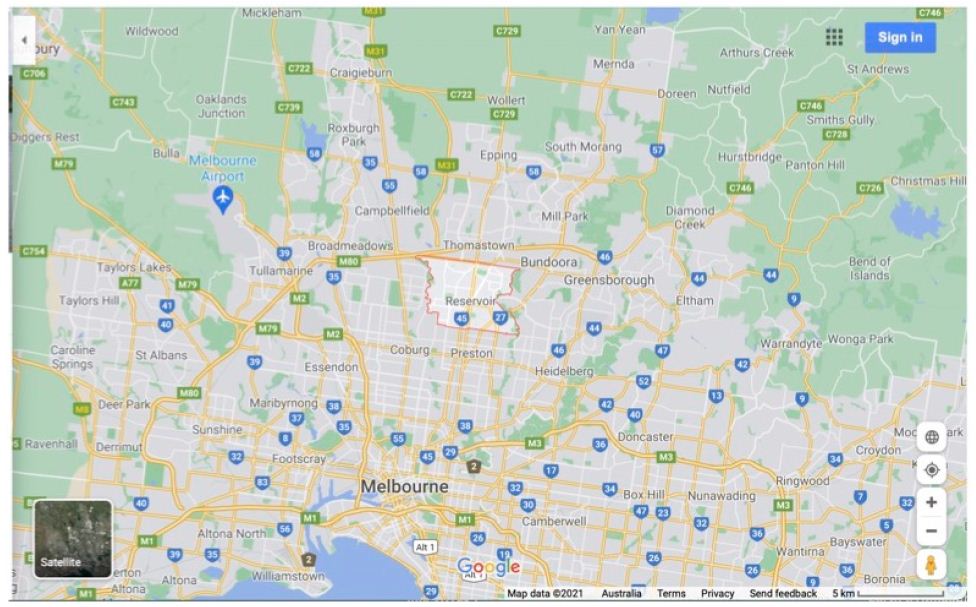

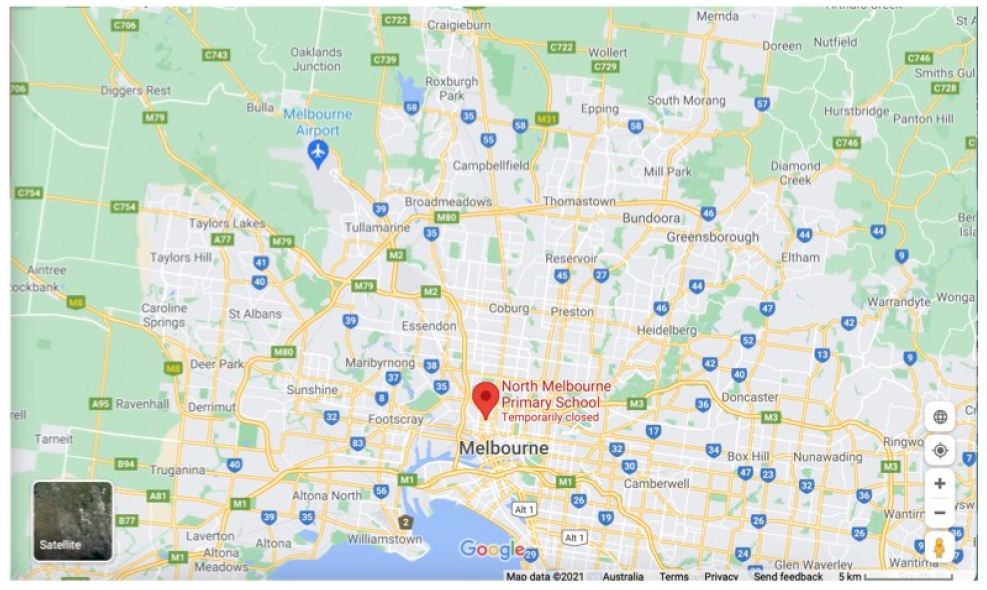

To focus on the relevant geographical infected Melbourne region, Figures 4A and 4B show Google Maps of the West-North Melbourne arc where the great majority of waste water catchment COVID-19 fragment detections have been found (April to early May 2021, Supplementary Information) and where the suddenly emergent mystery case-generated clusters of COVID-19 infections have later been found (below and Supplementary Information). A conservative estimate of the size of the region could be at least 1000Km2, stretching from Altona/Maidstone in Melbourne’s South West to the northern Whittlesea local government area (LGA) in which the suburb of Wollert is on the southern edge. The distance from Altona to the northern edge of Whittlesea LGA is at least 30 Km.

Figure 4A: Map West-North Melbourne Infected zones centred on “Reservoir”.

Weather in Melbourne and Environs through April into May 2021

There was significant April rain in greater Melbourne, usually at night and cold, on 9th (6.2mm), 10th (0.2 mm), 11th ( 3.4 mm), 12th (10 mm), 13th ( 0.6mm), 16th (1mm), 21st (10.4 mm), 23rd (0.4 mm), 25th ( 2.6 mm), 26th (1.2 mm), 27th (0.6mm), 28th ( 0.4mm) ; then again further rains well into May and June including severe flooding in the same regions covered in the Google Maps above. Precipitation coming up from the Southern Ocean in a SW to E direction (the typical prevailing way the winter weather visits Victoria) would be a necessary pre-condition for any tropospheric clouds of COVID-19 virion dust-associated particles to be brought to ground.

PCR COVID-19 Fragments Detected in Waste-Water Catchments Prior to Sudden Outbreak

The West-North arc and range of these detections is specifically covered in the Supplementary Information. They occurred during a period when no COVID-19 cases had been detected for many weeks (prior to May 11). These significant PCR detection signals occurred in late April early May before ‘Wollert Man’ the putative infective P-to-P trigger for the entire outbreak (see below and Supplementary Information) left the Adelaide quarantine hotel (May 4) and cover the same environment footprint where all the key putative mystery cases have been reported or deduced to have emerged. Thus, significant environmental contamination with COVID-19 genomes appears to have occurred and are manifest in waste-water catchment reservoirs in the W-N arc under discussion and analysis – it stretches incredulity that all the PCR fragments signals, in the face of massive dilution factors, are due to undetected high-rate urine shedders of COVID-19 virions by undetected asymptomatic infected subjects. The maps in Figures 4A and 4B can assist in visualising this COVID-19 fragment footprint in association with Supplementary Information.

Figure 4B: Map West-North Melbourne Infected zones centred on “North Melbourne Primary School”.

Analysis of Key Mystery Cases and Clusters

The caveats to this analysis are the absence of meta-data (ethnicity, clinical status, exact likely locations at infection) and the non-availability of exact COVID-19 genomic sequence(s) apart from muted PANGO variant of the infected subjects as well as considerable mis-information about each case in the mass media. There is only limited knowledge of the genomic sequence (shown in Figure 3) – some are either Indian variant kappa (B.1.617.1) or delta (B.1.617.2) as assigned below. When it was neither variant that was acknowledged in the press release we can only deduce that in that particular mystery case the sequence was “one of concern” as summarised in Figure 3 and Table 2. All the key public information around the origin of each mystery cluster is provided in the Supplementary Information for the reader to independently weigh up the evidence pro and con. In our considered view every case in the list below is a real mystery community transmission- no definitive genomic links nor P-to-P contact links with any other cluster. There has been considerable speculation in the mass media with state-wide (and even nation-wide) searches for the ‘missing links’ between clusters. They have not been found. To claim, as indicated in Materials & Methods, that Wollert Man or those in the larger Whittlesea LGA cluster are of the kappa Indian variant does not constitute evidence of a direct genomic link-in a situation as in Wollert v Whittlesea where no direct physical P-to-P links can be established. The article by The Australian’s Stephen Lunn on the origins of ‘Wollert Man’ catching a kappa variant by a putative fleeting 18 second contact in a corridor at the Playford quarantine hotel in Adelaide CBD cannot be taken seriously in the light of all the other epidemiological evidence (discussed below)

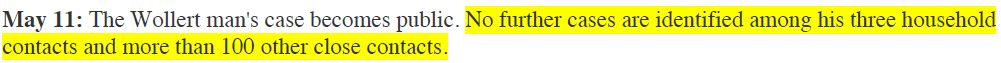

. Wollert Man (Indian Variant Kappa B.1.617.1)

Wollert Man, a 30 yr male returned home to Australia on April 20 from India via Adelaide airport and went into hotel quarantine. Over the next 2 weeks he had 3 negative PCR tests. On May 4 he travelled to Adelaide airport, caught a plane to Melbourne, travelled from the airport by Sky bus to Melbourne’s Southern Cross Station in the CBD, then caught the train north to Wollert, where he lived. According to reports he had some symptoms on May 8 and was PCR positive on May 11. His close contacts in the household have not become PCR positive. He had limited movement while in Wollert (in the Whittlesea LGA) but all subsequent tests on all those putatively contacted by him on his May 4 travel to Wollert and since (several hundred contacts) have scored PCR negative. In addition there was no transmission of the Playford hotel kappa Indian variant in Adelaide or anywhere in South Australia. The later kappa Indian cluster in Whittlesea LGA (on May 24) some 5 to 10 km from his Wollert home has no direct link to Wollert man- only the loose ‘kappa variant’ associations highlighted by the media and the Victorian Department of Health discussed already and in Materials and Methods (and Supplementary Information).

The most parsimonious interpretation of these data is that Wollert Man became infected when he returned to the already COVID-19 contaminated environment in Wollert on his return. He did not overtly transfer the infection after that date. This is a real genuine in-fall infection from the troposphere with an already human passaged common Indian variant (Table 2).

. Whittlesea Cluster (Indian Variant Kappa B.1.617.1)

This is a much larger cluster that emerged suddenly on May 24 and grew to about 20 cases in a few days (Figure 2), then to even greater numbers > 60 cases (Figure 3 and Supplementary Information). We have established there is no link with Wollert Man. We have no idea if there is more than one kappa mystery infection that initiated the P-to-P expansion. It is conceivable there may have been more than one pro-band. The situation remains confused and that point is not resolved. This cluster is not linked genomically or by any P-to-P contact with the other mystery clusters (below).

. Arcare Outbreak (Variant Non-Indian Kappa or Delta)

This case appeared suddenly on May 30 2021 in a 55 yr female carer at the Arcare aged care facility in Maidstone, West Melbourne (see Supplementary Information). It was passed to several elderly residents (> 80 yr) and also to another female carer who was also working in another local aged care facility (Sunshine). Of interest the 55 yr female carer had already had one COVID-19 vaccination, and the resident she passed it to (90 yr male) had a full course of two vaccinations. The elderly infected residents were transferred to hospital and seem to have recovered at time of writing. The Arcare facility is in lockdown at time of writing.

. Delta Cluster, Nth Melbourne (Indian Delta B.1.617.2)

This cluster emerged around June 4. It involved two families from North Melbourne who travelled together on holiday to the South Coast of NSW in the same large people moving van. Most members of that travelling group have become PCR positive. There are no physical or genomic links to any other cluster. But a supposed link with a ‘delta’ Indian variant brought from overseas by a Sri Lankan traveller to Melbourne has been hypothesized (see Supplementary Information). The most parsimonious explanation is this is a genuine mystery cluster as recognized by authorities. Whether one or several mystery infected probands in that van is responsible for initiating P-to-P spreads is not known.

. Reservoir Cluster (Variant Non-Indian Kappa or Delta)

This appeared suddenly on June 10 2021 and “includes a man in his 80s, a woman in her 70s, a man in his 50s and a man in his 20s who all live in the same household in Reservoir in Melbourne’s northern suburbs” (see Supplementary Information). There is no genomic or physical P-to-P link with any other cluster. It is clear the coronavirus variants driving the mystery clusters in the Victoria outbreak are diverse and typical of prior P-to-P passaged virus variants (Table 2). Where did they suddenly and mysteriously come from? This, we would argue, is a classic signature of spot “infections from the sky” over a regional arc known to have been previously contaminated with COVID-19 genomes on a regional scale. So all these cases are fully consistent with an aerial pathogenic attack from the troposphere, contaminating the environment and capriciously infecting unsuspecting victims as we have discussed in other recent papers.

Possible Explanations

Ab Initio haplotype sorting of meteorite dust raw virus seems highly unlikely given the clear evidence of complex human-passaged variants, many of which appear to have come from the Indian subcontinent epidemic (Table 2). The variant diversity in India is remarkably wide, and not confined to the main “Indian variants” kappa and delta. It includes even the ‘UK Mutant’ (B.1.1.7) which has become engaged in the Indian epidemic (Figures 1, 3 and Table 2). Indeed, in a sample of recent Indian PANGO variants that were uploaded to NCBI Virus we find at least 5 that are of concern in Victoria (Figure 3 and Table 2) have also been found in India. Thus PANGO variants and numbers uploaded in this small sample, as determined over the first two hundred upload web pages – each page can accommodate 200 entries- on June 6 and 7 (in brackets) are : B.1.1.7 (11), B.1.617.1 (4), B.1.617.2 (33), B.1.36.8(10), B.1.36 (14), B.36.10 (1), B.1 (2), B.1.1.216 (3), B.1.367 (2), B.1.1 (4), B.1.1.306 (1), B.1.36.17 (1), B.1.351, (5), B.1.427/B.1.429 (2) (see Supplementary Information). So just how did these mature human-passaged Indian variants appear mysteriously in Victoria from a tropospheric in-fall?

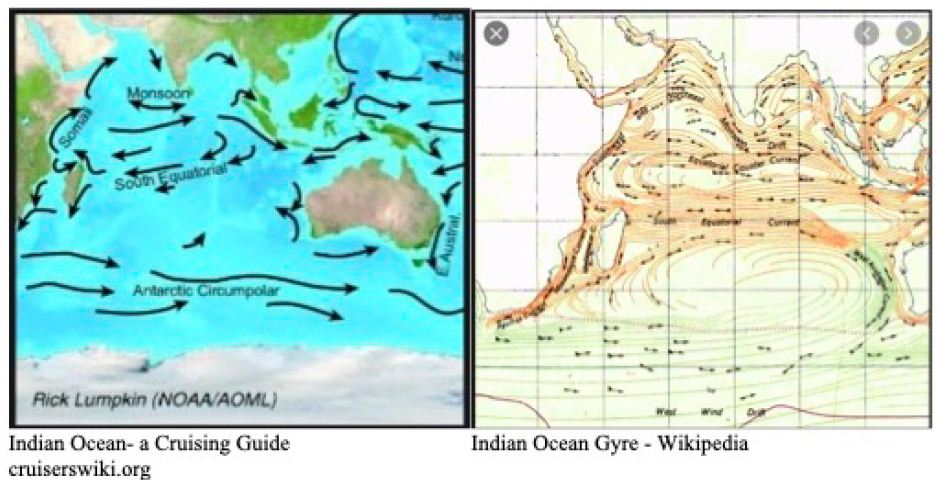

The recent outbreak in India is massive and cataclysmic. It has engaged almost all Indian provinces suddenly across the entire sub-continent (not shown, use URL in Figure 1 to check this fact out). We have speculated in the past that it has been triggered on scale by a viral laden dust comet dust in-fall off the 40o N Latitude band on the southern side of the Himalayan Mountains [3]. However, we can plausibly include, at a slightly later time, the Sri Lankan and Maldives outbreaks as also coming from India (Supplementary Information). Indeed, as we continue to marshal the relevant evidence, there is in fact a temporal sequential order of outbreaks further south on that same longitude line down the East African coast. New COVID-19 outbreaks of variable magnitude, temporally following India, appear evident in Kenya, Madagascar and South Africa. It is thus conceivable that the putative virus-laden plume (heterogeneous collection of human passaged COVID-19 viral variants) over India has been transported by tropospheric Indian Ocean and Southern Ocean prevailing winds to also cause the comparatively minor outbreak in Victoria, Australia in May-June 2021.

The prevailing winds in the Indian and Southern Ocean (Figure 5) make this global tropospheric transport route entirely credible. And indeed, the recent “upticks” in the rolling waves of Chilean epidemics suggest that the entire Roaring Forties 40o S line may now be entrapped by the tropospheric viral clouds from the plume of the Indian epidemic (Supplementary Information). Other independent evidence supporting this interpretation has been documented in the past for the global transport and spread of previous Influenza pandemics by global weather and wind systems [10,19]. Further, in the case COVID-19 in the first few months of the pandemic, the Wuhan plume carrying the dominant human passaged haplotype (L) appeared to have crossed the North Pacific by mid-February 2020 to infect passengers on the Grand Princess cruise ship who displayed genomic sequences of unmutated or lightly mutated L haplotype as discussed [3,18].

Figure 5: Prevailing winds in Indian and Southern Oceans

Google link to Indian Ocean winds at: https://tinyurl.com/43axd6f8

Conclusions

It is plausible in the light of this analysis of a defined small COVID-19 outbreak that other global transfers of viral plumes are conceivable. The “UK Mutant” B.1.1.7 is now widespread and very common in the USA (inspection of the very large numbers of uploads of B.1.1.7 variants to NCBI Virus confirms this impression) and including many parts of Europe. These global transportations again via lower-level E-to-W and W-to-E tropospheric winds seem plausible given the expected size of the viral plume over the UK epidemic Dec-Feb (Figure 1). There are many unknowns on the size and potential rising-height of the putative viral plumes, so plausible speculation is required. From available epidemiological data (e.g. Figure 1) which suggest an estimated 10 million active Indian cases at any given time over several weeks (20 days of say 500,000 cases per day), we would have ~ 107 virus exhalers who undoubtedly contribute virions into the lower atmosphere. If we assume that each infected “exhaler” conservatively contributes 1012 aerosol virions we would have a total of 1019 virions potentially arising from the surface of the Indian subcontinent. Such virions which pass through regions of high humidity would be expected to acquire outer mantles of water ice that could help to retain viability to some degree. Fukuta et al. have recently shown that COVID-19 remains highly infectious for prolonged periods in cold and wet conditions [24]. In addition, Kwon et al. [25] have determined the stability of the virus in a variety of biological fluids (nasal mucus, sputum, saliva, tear, urine, blood, and semen) and “it remained infectious significantly longer under winter and spring/fall conditions than under summer conditions”. This suggests that dispersed viruses in aerosol biological fluid protective wraps may add to putative stability. If say 10% of these aerosol-protected virions survive lofting into the troposphere and subsequent wind transport, we have some 1018 virions (all amplified by victims in India) that are in circulation and which could contribute to the outbreaks of the so-called mystery clusters in Victoria, Australia. Indeed as this paper was being submitted it seems that the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou may be engaged in a sudden tropospheric strike of variants from India. Further, many other Northern Hemisphere countries (Russia, UK, USA) are also reporting the sudden spread of the Indian delta variant on real population wide scale (for news links see Supplementary Information File)

Given these developments, and on reflection, the sudden large outbreak in Sri Lanka October 4 – 6 2020 may well have been due to the 1st Wave Indian human-passaged viral plume (see Figure 1 and Supplementary Information). In contradistinction, the recent In Press report of Althoff et al. [26] of early spot detections and spreads of COVID-19 (late 2019-early 2020) suggest early fragmented in-fall of small clouds of raw (non P-to-P passaged) meteorite dust COVID-19 from the stratosphere on the 40o N latitude line as discussed viz [14]. “7 individuals had detectable SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin G prior to the first confirmed case in the states of Illinois, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Mississippi, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 infections were occurring weeks prior to recognized cases in at least 5 US states [26].”

What lessons can we learn? Certainly, near-Earth surveillance of incoming pathogens from space, such as the suggested “Hoyle” shield needs to be an international imperative [27], as often reiterated by us [3,28], including for monitoring for tropospheric global transport of viral plumes as discussed here. But it seems also that once a viral pandemic is already underway, rising viral-plumes from major infected zones can potentially be transported to infect other global regions on a mass scale. Indeed pathogenic re-circulation via the troposphere during a pandemic is a major factor to consider for societies whose thinking seems restricted to “hard lockdowns and social distancing” to prevent or alleviate the spread of airborne viruses. If it is considered feasible a procedure by which the lower atmosphere and environments of infected areas could be sprayed with suitable disinfectants from the air must surely deserve serious attention. Face masks may be useful during an actual tropospheric in-fall event but may not work in the way the health authorities have advocated during a real mass outbreak on the scale of trillions of infectious virions falling from the sky. All the evidence from the 2nd Wave in the Victorian 2020 epidemic suggests the Stage 4 lockdown had no impact whatsoever on the course of the epidemic [3], a conclusion supported by critical analysis of similar lock downs in the USA [29].

What of the immediate future? Has all the raw cometary dust-protected virus or the P-to-P plumed-virus (almost certainly assisted and protected by pollution particles) [30,31], washed down from the troposphere? The Spanish Flu took two years to run its full course. COVID-19 is nowhere as lethal but its global reach is similar, implying a similar magnitude of initiating viral inoculation. If that is a valid comparison then full viral wash down could perhaps take another 6 months. This time frame is not incompatible with other micron-sized particle falling-rates as estimated for wash down of radioactive tracers following upper-atmosphere nuclear tests in the late 1950s [2]. In conclusion we stress that as scientists we have a responsibility to accept whatever facts that the universe presents us without fear or favour. Distorting or even simply tweaking emerging facts in order to fit a long-established paradigm should be avoided at all cost.

Acknowledgement

We thank Max K. Wallis for critical discussions on the pandemic contributions of rising plumes of P-to-P virus, particularly the Wuhan COVID-19 plume of January 2020. George Howard is thanked for bringing to our attention the recent study by Althoff KN, Schlueter DJ, Anton-Culver H, Cherry J, Denny JC, et al. (2020). We thank John A Schuster for a critical reading of the manuscript first draft.

References

- Wickramasinghe NC, Steele EJ, Gorczynski RM, Temple R, Tokoro G, et al. (2020) Comments on the Origin and Spread of the 2019 Coronavirus. Virology: Current Research 4:1. DOI: 10.37421/Virol Curr Res.2020.4.109

- Steele EJ, Gorczynski RM, Lindley RA, Tokoro G, Temple R, et al. (2020) Origin of new emergent Coronavirus and Candida fungal diseases- Terrestrial or Cosmic? Advances in Genetics 106: 75-100. [crossref] https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.adgen.2020.04.002

- Steele EJ, Gorczynski RM, Lindley RA, Tokoro G, Wallis DH, et al. (2021) Cometary Origin COVID-19 Infect Dis & Therapeutics 2: 1-4. DOI: 31038/IDT.2021212

- Wainwright M, Wickramasinghe NC, Narlikar JV, Rajaratnam P, Perkins Joy (2004). Confirmation of the presence of viable but non-culturable bacteria in the stratosphere. J. Astrobiology 3: 13-15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1473550404001739

- Wainwright M, Wickramasinghe NC, Tokoro G (2021) Neopanspermia – evidence that life continuously arrives at the Earth from space. Advances in Astrophysics. In Press

- Grebennikova TV, Syroeshkin AV, Shubralova EV, Eliseeva OV, Kostina LV, et al. (2018) The DNA of bacteria of the world ocean and the Earth in cosmic dust at the international space station. World J. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7360147

- Steele EJ, Al-Mufti S, Augustyn KA, Chandrajith R, Coghlan JP, et al. (2018) Cause of Cambrian Explosion: Terrestrial or Cosmic? Biophys. Mol. Biol 136: 3-23. [crossref] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2018.03.004

- Steele EJ, Gorczynski RM, Lindley RA, Liu Y, Temple R, et al. (2019) Lamarck and Panspermia – On the Efficient Spread of Living Systems Throughout the Cosmos. Biophys. Mol. Biol 149: 10-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2019.08.010

- Steele EJ, Gorczynski RM, Rebhan H, Carnegie P, Temple R, et al. (2020) Implications of haplotype switching for the origin and global spread of COVID-19 Virology: Current Research DOI: 10.37421/Virol Curr Res.2020.4.115

- Hoyle F, Wickramasinghe NC (1979) Diseases from Space JM Dent Ltd, London.

- Hoyle, F and Wickramasinghe, NC. (2000) Astronomical Origins of Life: Steps Towards Panspermia. Klower Academic Publishers, Dordrechl, The Netherlands.

- Steele EJ, Wickramasinghe NC (Editors) (2020) Cosmic Genetic Evolution. Advances in Genetics. 106: 2-143.

- Wickramasinghe NC, Steele EJ, Gorczynski RM, Temple R, Tokoro G, et al. (2020) Growing Evidence against Global Infection-Driven by Person-to-Person Transfer of COVID-19 Virology: Current Research 4:1. DOI: 10.37421/Virol Curr Res.2020.4.110

- Wickramasinghe NC, Steele EJ, Gorczynski RM, Temple R, Tokoro G, et al. (2020) Predicting the Future Trajectory of COVID-19. Virology: Current Research 4:1. DOI: 10.37421/Virol Curr Res.2020.4.111

- Wickramasinghe NC, Wallis MK, Coulson SG, Kondakov A, Steele EJ, et al.(2020) Intercontinental Spread of COVID-19 on Global Wind Systems Virology: Current Research 4:1.DOI: 10.37421/Virol Curr Res.2020.4.113

- Howard GA, Wickramasinghe NC, Rebhan H, Steele EJ, Gorczynski RM, et al. (2020) Mid-Ocean Outbreaks of COVID-19 with Tell-Tale Signs of Aerial Incidence Virology: Current Research 4:2. DOI: 10.37421/Virol Curr Res.2020.4.114

- Wickramasinghe NC, Steele EJ, Nimalasuriya A, Gorczynki RM, Tokoro G, et al. (2020) Seasonality of Respiratory Viruses Including SARS-CoV-2 Virology: Current Research 4:2. DOI: 10.37421/VCRH.2020.4.117

- Steele EJ, Lindley RA (2020) Analysis of APOBEC and ADAR deaminase-driven Riboswitch Haplotypes in COVID-19 RNA strain variants and the implications for vaccine design. Research Reports. https://companyofscientists.com/index.php/rr

- Hammond GW, Raddatz RL, Gelskey DE (1989) Impact of atmospheric dispersion and transport of viral aerosols on the epidemiology of Influenza. Reviews of Infectious Disease 11: 494- 497. [crossref] https://doi.org/10.1093/clinids/11.3.494

- Rambaut A, Holmes EC, O’Toole Á, Hill V, McCrone JT, et al. (2020) A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS- CoV-2 to assist genomic epidemiology. Microbiol 5: 1403-1407. [crossref] https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-0770-5

- Forster P, Forster L, Renfrew C, Forster M (2020) Phylogenetic network analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 117: 9241-9243. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2004999117

- Eigen M, Schuster P (1979) The Hypercycle: A Principle of Natural Self-Organization. Springer, Berlin.

- Andino R, Domingo E (2015) Viral quasispecies. Virology 479-480: 46-51. [crossref] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2015.03.022

- Fukuta M, Mao ZQ, Morita K, Moi ML (2021) Stability and Infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 and viral RNA in Water, Commercial Beverages, and Bodily Fluids. Microbiol 12: 667956. [crossref] https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.667956

- KwonT, Gaudreault NN, Richt JA (2021) Seasonal Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in Biological Fluids. Pathogens 10: 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10050540

- Althoff KN, Schlueter DJ, Anton-Culver H, Cherry J, Denny JC, et al. (2020) Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in All of Us Research Program Participants, January 2-March 18, 2020. Clinical Infectious Diseases. https://academic.oup.com/cid/advance-article/doi/10.1093/cid/ciab519/6294073

- Smith WE (2013) 2013; Life is a cosmic phenomenon: the Search for Water evolves into the Search for Life. Hoover RB, Levin GV, Rozanov AY, Wickramasinghe NC (Eds.). Proc. SPIE 8865, Instruments, Methods, and Missions for Astrobiology XVI. San Diego, California, United States. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2046862.

- Qu J, Wickramasinghe NC (2020) The world should establish an early warning system for new viral infectious diseases by space-weather monitoring. MedComm 1: 423-426. DOI: 10.1002/mco2.20

- Luskin DL (2020) The failed experiment of COVID-19 lockdowns. The Wall Street Journal. Sept 2.

- Coccia M (2020) Factors determining the diffusion of COVID-19 and suggested strategy to prevent future accelerated viral infectivity similar to COVID. Science of the Total Environment 729: 138474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138474

- Martelletti L, Martelletti P (2020) Air Pollution and the Novel Covid-19 Disease: a Putative Disease Risk Factor. SN Compr. Clin. Med 2: 383-387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00274-4