Abstract

Introduction: COVID 19, the global pandemic that was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and adversely affected global life style, was reported in Jordan in March 2020. Due to its high contagious dissemination, the rapid virus spread caused global lifestyle modifications. Medical schools in Jordan as other facilities were highly affected and had alterations related to education. Here we focus, discuss and conclude the final alterations impact according to students impressions to end up with recommendations for future pandemic education.

Methods: This cross sectional, prospective study explores the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on medical students’ academic performance in Jordan from their point of view. A survey questionnaire was developed to investigate the issue related to the study subject and to answer certain questions. Mainly we needed to find out if COVID-19 pandemic affected medical students’ academic performance in Jordan? In which aspects? And in what direction? Due to the nature of this study, and the circumstances during the study period, an online survey questionnaire was conducted through Google Forms and reflected the found outcome.

Results: The study population consists of approximately 6500 representing all medical students in each academic year from the six medical schools in Jordan. Appropriately found formula was used to determine the required sample size. Finalising that most but not all criteria used measures were negatively affected.

Conclusion: All the academic performance components -that we have assumed- have been affected negatively by the pandemic with the exception of medical knowledge. E-learning infrastructure and pre-experience in distance learning might have an improvement effect and may be better outcome than classical learning.

Introduction

COVID 19, the global pandemic that was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and adversely affected global life style, was reported in Jordan in March 2020 [1]. Due to its high contagious dissemination and the variable symptoms from subclinical to severe lethal pneumonia [2,3], the rapid virus spread caused global lifestyle modifications. Most governments worldwide applied new regulations trying to flatten the escalating spread curves caused by the pandemic. Face masks wearing, strict hygiene, social distancing, travel restrictions, borders closing, and closing schools, colleges and Universities physically were all utilized. The higher educational institutions around the world have been fully or partially, closing their campuses to limit the rapid spread of COVID19 infection. All those alterations led to massive disrupt at all educational levels in general [4]. Therefore, such consequences forced the worldwide higher educational institutes to adopt distance learning mode. Taking in consideration that any unforeseen judgment would probably lead to massive derangement in the critical and civilian cervices [5].

Moreover, all students perspectives in general, were distorted due to the misbelief of expected curricula modification to fit for the new so-called remote learning. In addition, remote electronic exams (E-exams) were considered as the new mode of assessment. Distance learning, teaching, and assessment were never the fundamental one applied in Jordan schools of medicine. Lack of experience in both parties of electronic services created an unsecured atmosphere. The issue of having distance learning as being the solely one used in medical schools was growing over and over. Debate started to expand between experts whether distance learning decision was injudicious up to many where others considered it sapient [6].

Concerning students in medical schools in Jordan, there was an apprehension among them about that newly developed assessment mode [7]. The panic was higher between clinical years medical students as medicine studying depends in its majority on clinical, and practical part especially in the last three years. Their fear was understandable as the decision of distance learning was suddenly taken and not gradually as expected to be. Gradual transition was about to be justified especially if proper preparation and precautions were taken in consideration before the complete sudden distance education decision.

However, the unprepared technical infrastructure will always be an obstacle for distance learning indifferent of the educational level. Malfunctions, bugs, connection errors, inability to connect, sudden disconnection, or even video and audio technical problems are all challenges faced by best prepared networks. Dishonesty of either side whether students or lecturers was always considered an addressed issue and taken seriously due to its major and catastrophic consequences. Nevertheless, obscurant credence started to be a new challenge for medical schools to face. That belief of students and parents reached to the extent that many appealed for money refund. Accordingly, proving efficiency and ability to continue online without affecting the quality of learning was a new challenge for all educational institutions to take over. Hybridisation of conventional, as well as online educational programme was applied by many institutions as a way to keep the balance between safety during pandemic and high quality education [8]. For instance, all lectures and presentations which were considered theoretical were given online, while patient based practice sessions were in hospital module of learning, after taking all precautions as per ministry of health instructions.

Nevertheless, medical educational system continued to pursue its utmost efforts to facilitate the informations availability. Undergraduate medical student’s opinions about the modified system attitude were variable, and here we try to focus on their expression and to illustrate their point of view on the newly adopted distance learning era [9-13].

In this article, we have conducted a cross-sectional online survey study among all six years medical schools in Jordan to explore the above mentioned challenges, and the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on medical school students’ academic performance.

Materials and Methods

This cross sectional, prospective study explores the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on medical students’ academic performance in Jordan from their point of view. A survey questionnaire was developed to investigate the issue related to the study subject and to answer certain questions. Mainly we needed to find out if COVID-19 pandemic affected medical students’ academic performance in Jordan? In which aspects? And in what direction? Due to the nature of this study, and the circumstances during the study period, an online survey questionnaire was conducted through Google Forms. The form distributed to the study cohort could have been found at: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1N0J8hiVVzYw7iV6zcPhvzRy_q_3NvdzxKlrovLVnqCg/prefill?skip_itp2_check=true. The targeted study population is the medical school students in Jordan indifferent in which year, meanwhile, basic and clinical years included. From all medical schools in Jordanian Universities, students were invited to participate in the study by completing the form online. The form was available through an invitation on known web platforms, sites and pages to students. Participation was voluntary and completely anonymous for the period from beginning of February till the end of it same year (2021). The study was approved by the ethical committee, and has IRB approval number 219/132/2020 from Jordan University of Science and Technology (JUST), Irbid, Jordan. The University of Jordan (UJ), Jordan University of Science and Technology (JUST), Mutah University (MU), The Hashemite University (HU), Al-Balqa Applied University (BAU), and Yarmouk University (YU) registered at study time students from medical schools were all eligible to participate in the study.

Variable Selection

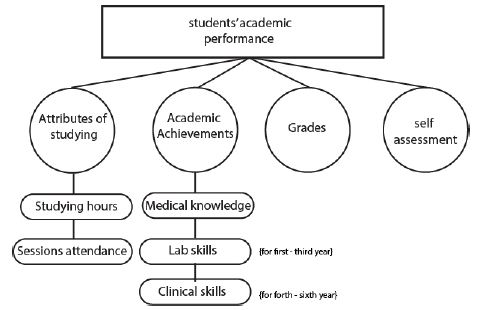

The following variables are developed from literature reviews and serve as indicators of students’ academic performance:

1) Academic achievement which includes:

A. Medical knowledge.

B. Laboratory skills which applied for basic science years students only {first to third year}.

C. Clinical skills which applied for clinical science years students only {forth to sixth year}.

2) Attributes of studying which includes:

A. Studying hours

B. Sessions attendance

3) Seasonal grade.

4) Self-Assessment.

Based on the aforementioned variables, diagram 1 represent the operational definition of the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic performance.

The reliability of Academic performance as indicated by the reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s Alpha=(0.723)). Indicates adequate reliability.

Hypothesis, test of hypothesis and sampling:

The hypotheses for this research are to test whether there is any significant impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic performance, and to test whether there is any association between specific demographic characteristics of the students and the impact of COVID-19 on their academic performance.

A. There is no impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic performance.

A1. There is no impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic achievement.

A1.1. There is no impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ medical knowledge.

A1.2. There is no impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ laboratory skills.

A1.3. There is no impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ clinical skills.

A2. There is no impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ attributes of studying.

A2.1. There is no impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ studying hours.

A2.2. There is no impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ attendance.

A3. There is no impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ grades.

A4. There is no impact of COVID-19 pandemic as self-assessed by students.

B1. There is no association between students’ Gender and the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic performance.

B2. There is no association between students’ Academic year and the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic performance.

B3. There is no association between students’ High school and the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic performance.

B4. There is no association between students’ number of family members and the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic performance.

B5. There is no association between students’ monthly family income and the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic performance.

Due to the nature of this empirical study, an online survey questionnaire was conducted through Google Forms. The questionnaire was published through social media (multiple website, and platforms like Facebook groups for medical students in Jordan). The respondents were asked to evaluate the selected variables in a three point Likert scale, with 3=positively/increased, 2=neutral/not changed, 1=negatively/decreased.

One sample Student’s t-test is used to test hypotheses (A-A4). A t-test is a statistical hypothesis test in which the test statistic follows a Student’s t distribution if the null hypothesis is supported. It is most commonly applied when the test statistic would follow a normal distribution if the value of a scaling term in the test statistic is known. The one sample t-test requires that the dependent variable follow a normal distribution. When the number of subjects in the experimental group is 30 or more, the central limit theorem shows a normal distribution can be assumed. 95% of the t-Tests two tailed probability level was selected to signify the differences between preferences. The estimate value for testing hypotheses in this study is 2, which is neutral/not changed. It shows no differences in academic performance in the presence of the pandemic. A Pearson’s correlation test was run to test hypotheses (B1-B4). The respondents were asked to evaluate the selected variables in three points. One sample Student’s t-test is used to test hypotheses (A-A4). A t-test is a statistical hypothesis test in which the test statistic follows a Student’s t distribution if the null hypothesis is supported. It is most commonly applied when the test statistic would follow a normal distribution if the value of a scaling term in the test statistic is known. The one sample t-test requires that the dependent variable follow a normal distribution. When the number of subjects in the experimental group is 30 or more, the central limit theorem shows a normal distribution can be assumed. 95% of the t-Tests two tailed probability level was selected to signify the differences between preferences. The estimate value for testing hypotheses in this study is 2, which is neutral/not changed.

Results

Between Feb 2, 2021 and Feb 27, 2021. A total of 369 sixth year medical students in Jordan responded to the questionnaire, and of those who did, a number of 16 responses were excluded due to lack of accuracy-halo effect/since they answered a question not supposed to be answered. With 353 valid responses for analyses, representing 95% of the total was surveyed.

The study population consists of approximately 6500 representing all medical students in each academic year from the six medical schools in Jordan. The Slovin’s formula was used to determine the required sample size.

Sample Size=N/(1 + N*e22) where: N=population size. e=margin of error.

Solving the formula using e=0.05, N=(6500) sample size of (364) was yielded.

Table 1 presents the distribution of the students according to specific Demographic characteristics:

Table 1: Demographic characteristics

|

Frequency |

Percent |

||

| Gender | Male |

179 |

50.7 |

| Female |

174 |

49.3 |

|

| Residence | Central region |

207 |

58.6 |

| Northern region |

97 |

27.5 |

|

| Southern region |

49 |

13.9 |

|

| University | Al-Balqaʼ Applied University (BAU) |

119 |

33.7 |

| Jordan University of Science and Technology (JUST) |

59 |

16.7 |

|

| Mutah University (MU) |

39 |

11.0 |

|

| The Hashemite University (HU) |

43 |

12.2 |

|

| The University of Jordan (UJ) |

19 |

5.4 |

|

| Yarmouk University (YU) |

74 |

21.0 |

|

| Academic year | First year |

48 |

13.6 |

| Second year |

83 |

23.5 |

|

| Third year |

47 |

13.3 |

|

| Forth year |

48 |

13.6 |

|

| Fifth year |

73 |

20.7 |

|

| Sixth year |

54 |

15.3 |

|

| High school | private school |

191 |

54.1 |

| public school |

162 |

45.9 |

|

| Number of Family members | Small family |

142 |

40.2 |

| Medium family |

188 |

53.3 |

|

| Large family |

23 |

6.5 |

|

| Monthly family income | Low income |

125 |

35.4 |

| Moderate income |

112 |

31.7 |

|

| High income |

116 |

32.9 |

|

Table 2 presents the test results of One-Sample t-Test, with mean differences, t values, degrees of freedom, and two tailed significances of these tests.

Table 2: COVID-19 pandemic effect on medical students’ academic performance and its components

|

Test Value = 2 |

||||||

|

t* |

df** | P value |

Mean Difference |

95% Confidence Interval of the Difference |

||

| Lower |

Upper |

|||||

| Academic performance |

-8.020 |

352 | .000 | -.21211 | -.2641 |

-.1601 |

| Academic achievement |

-7.725 |

352 | .000 | -.23654 | -.2968 |

-.1763 |

| Progress in medical knowledge |

.274 |

352 | .784 | .01133 | -.0699 |

.0926 |

| Progress in laboratory skills |

-8.910 |

177 | .000 | -.46629 | -.5696 |

-.3630 |

| Progress in clinical skills |

-10.661 |

174 | .000 | -.50286 | -.5960 |

-.4098 |

| Attributes of studying |

-7.604 |

352 | .000 | -.23229 | -.2924 |

-.1722 |

| Average daily studying hours |

-2.796 |

352 | .005 | -.11898 | -.2027 |

-.0353 |

| Sessions attendance |

-9.697 |

352 | .000 | -.34561 | -.4157 |

-.2755 |

| Seasonal grade |

-2.306 |

352 | .022 | -.09632 | -.1785 |

-.0142 |

| Self-assessment |

-7.289 |

352 | .000 | -.28329 | -.3597 |

-.2069 |

*t value

**Degree of freedom

The mean for Academic performance score and all of its components – except medical knowledge- scores were statistically significantly lower than the neutral score of 2 (p<0.05). With progress in clinical skills having the highest mean difference of 0.49 and Seasonal grade having the lowest mean difference of -.10. Therefore, we can reject the null hypotheses (A, A1, A1.2, A1.3, A2, A2.1, A2.2, A3, and A4) and accept the alternative hypotheses. And accept the null hypothesis A.1.1.Thus the Academic performance and all of its components except medical knowledge is negatively affected by COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 3 presents the test results of Pearson’s correlation test between specific demographic characteristics and academic performance.

Table 3: Relationship between specific demographic characteristics and impact of COVID-19 pandemic on medical students’ academic performance

|

Gender |

Residence | University | Academic year | High school | Family member groups |

Monthly family income level |

||

| Academic performance |

Pearson Correlation |

-.071 |

.077 | .030 | .159** | .049 | -.001 |

-.026 |

| p |

.183 |

.150 | .579 | .003 | .363 | .983 |

.624 |

|

| N |

353 |

353 | 353 | 353 | 353 | 353 |

353 |

|

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

There was a very weak, positive correlation between Academic year and Academic performance r=.159, N=353; the relationship was statistically significant (p=.003). However there were no statistically significant relationships between Academic performance and other demographic characteristics (p>.05). Therefore, we can reject the null hypothesis B2 and accept the alternative hypothesis. And accept the null hypotheses (B1, B3 and B4). According to the findings and statistics, the academic performance and all of its components except medical knowledge were negatively affected by COVID-19 pandemic.

Discussion

Since COVID 19 pandemic first appearance in Wuhan city in china, November 2019 and its spread over the world (9, 10, 11), it has been affecting almost all sectors of life and increasing efforts has been made to study that effect (12, 13), lock down have been held worldwide which led to a huge impact on economy, education and most importantly health regardless whether it was physical or mental health [14-17].

In this context, this study was conducted as to observe the impact of COVID 19 on the academic performance of medical students in Jordan Universities, and evaluate the effect on certain parameters like their medical knowledge, laboratory and clinical skills, their attendance, daily studying hours and their grades, and all that was viewed in regards to e-learning which was adopted as the learning method during the pandemic. This study was done on the 6 medical schools in Jordan and the sample was 353 medical students from all years.

Apparently, and according to our results illustrated; COVID19 pandemic has negative impact in all component measured by us of academic performance for medical students in Jordan (attributes of studying, average daily studying hours, sessions attendance, academic achievement, progression in laboratory and clinical skills, grades, and self-assessment) with the exception of medical knowledge progression as found in Tables 2 and 4.

Table 4: Components measured by us of academic performance for medical students in Jordan

|

|

Negative |

Neutral |

Positive |

|

| Total impact on academic performance | Frequency |

158 |

137 |

58 |

| Percent |

44.76 |

38.81 |

16.43 |

|

| Average daily studying hours | Frequency |

136 |

123 |

94 |

| Percent |

38.53 |

34.84 |

26.63 |

|

| Seasonal grade | Frequency |

127 |

133 |

93 |

| Percent |

35.98 |

37.68 |

26.35 |

|

| Attendance | Frequency |

161.00 |

153.00 |

39.00 |

| Percent |

45.61 |

43.34 |

11.05 |

|

| Progress in medical knowledge | Frequency |

104.00 |

141.00 |

108.00 |

| Percent |

29.46 |

39.94 |

30.59 |

|

| Progress in laboratory skills for (1st – 3rd year) | Frequency |

104.00 |

53.00 |

21.00 |

| Percent |

58.43 |

29.78 |

11.80 |

|

| Progress in clinical skills (for 4th-6th year) | Frequency |

100.00 |

63.00 |

12.00 |

| Percent |

57.14 |

36.00 |

6.86 |

The effect on daily studying hours and sessions attendance could be explained by the probability that students considered e-learning less serious and possibly there are difficulties in dealing with such kind of learning because it is an emerging one in medical schools in Jordan Universities. Moreover, resources limitation such as unavailability of proper internet connection in certain urban areas, and/or smart devices limited access by some students may have played a role and that could be indirectly observed through the participation in our study which is entirely dependant on digital platforms. Most of study participants are from central areas in Jordan (58.6%) where the most reliable internet is. On the contrary, contributors from northern and southern Universities where rural areas are, with unreliable internet connections represented 41.4% (27.5+13.9) as per (Table 1). Taking in consideration that students individual preferences, interests, vary from student to another [18].

Laboratory and clinical skills were the components that have been negatively most affected (mean difference=0.47, 0.5 respectively). We firmly believe that this effect is due to the fact that students have been away from the field of learning. Additionally, the suggested certainty related to the weaknesses of infrastructure in medical schools in Jordan to support appropriate e-learning which they believed it should have been far better that the existing [19]. Although some studies showed that laboratory skills can be acquired away from the lab by video feedback [20], the results we observed were against the results of those studies; and this can be explained by challenges found in Jordan Universities in supporting this kind of learning modality. Students in our study do believe that they substantially need to physically attend and participate in clinical rounds, take history and do physical examination to improve their clinical medical skills [21,22].

In contrast to other components, medical knowledge has shown no relation with the pandemic (p=0.784), we suggest that this is due to students ability to depend on self-studying from other resources outside the University premises. Books, slides, scientific papers, lectures, internet etc. participated to develop student’s medical knowledge. In addition, students platforms availability on the internet which facilitates knowledge sharing, and suggested sites between medical school students and their mentors again played distinguished part in improving faculty members and students medical knowledge [23].

Demographic characteristics in this study showed no relation (p>0.05) on the impact of COVID 19 pandemic on medical students academic performance with the exception of academic year (p=0.003). It showed only a weak positive effect (Pearson correlation=0.159) illustrated clearly in Table 3. The thing which can be explained by the fact that medical students autonomously progress in their years spent in medical schools. They perform more tests and sit for more evaluation exams, so more conjunction of knowledge and skills is met. Nevertheless, more development of cognition that makes them more independent in their self-developing [24]. Good example is that fourth year medical student is more likely to compensate the reduction in the quality and quantity than the second year medical student.

Alsoufi et al. found an accepted level of knowledge in medical students regarding e-learning in Libya in his study. In addition, they were concerned about how e-learning could be applied to provide clinical experience which depends heavily on bedside teaching [25].

Some other studies in other regions, specifically Kingdom of Saudi Arabia have shown acceptance in e-learning during COVID-19, showing better outcomes with promising potentials to prefer e-learning in medical education in the future [26]. As per experts, such findings could be related to better distance learning infrastructure and facilities.

The strength of this study is that it applied multiple measures (medical knowledge, laboratory and clinical skills, session attendance, daily studying hours, grades and self-assessment) to demonstrate and assess academic performance (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Definition of the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic performance

Certain limitations of this study could be addressed in future research are (low response, and absence of funding, limited number of studies on this topic).

More studies are still needed to evaluate the impact of distance learning under and free of the influence of certain pandemic.

Conclusion

All the academic performance components -that we have assumed- have been affected negatively by the pandemic with the exception of medical knowledge. E-learning infrastructure and pre-experience in distance learning might have an improvement effect and may be better outcome than classical learning.

References

- Al-Tammemi A (2020) The Battle Against COVID-19 in Jordan: An Early Overview of the Jordanian Experience. Front Public Health 8: 188. [crossref]

- Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, et al. (2020) Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 395: 1054-1062.

- Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN (2020) The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun 109: 102433.

- Malee Bassett R, Arnhold N (2020) World Bank Blogs; COVID-19’s Immense Impact on Equity in Tertiary Education.

- Bergdahl, N, Nouri, J (2021) Covid-19 and Crisis-Prompted Distance Education in Sweden. Tech Know Learn 26: 443-459.

- Zalat M, Hamed M, Bolbol S (2021) The experiences, challenges, and acceptance of e-learning as a tool for teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic among university medical staff. Plos One 16: e0248578. [crossref]

- Birch E, de Wolf M (2020) A novel approach to medical school examinations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Educ Online 25: 1785680. [crossref]

- Mishra L, Gupta T, Shree A (2020) Online teaching-learning in higher education during lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Educ Res Open 1: 100012.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, et al. (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395: 497-506. [crossref]

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, et al. (2020) Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 395: 507-513. [crossref]

- Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, et al. (2020) First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med 382: 929-936. [crossref]

- Khoo Erwin J, Lantos John D (2020) Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Paediatrica 109: 1323-1325. [crossref]

- Haleem A, Javaid M, Vaishya R (2020) Effects of COVID-19 pandemic in daily life. Curr Med Res Pract 10: 78-79. [crossref]

- Prickett, Kate C, Fletcher Michael, Chapple Simon, Doan Nguyen, Smith Conal (2020) Life in lockdown: The economic and social effect of lockdown during Alert Level 4 in New Zealand.

- Kapasia, Nanigopal, Paul, Pintu, Roy, et al. (2020) Impact of lockdown on learning status of undergraduate and postgraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in West Bengal, India. Children and Youth Services Review 116: 105194.

- Rajiv R, Ramachandran R, Surya J, Ramakrishnan R, Sivaprasad S, et al. (2021) Impact on health and provision of healthcare services during the COVID-19 lockdown in India: a multicentre cross-sectional study. BMJ open 11: e043590. [crossref]

- Adams-Prassl Abi, Boneva Teodora, Golin Marta, Rauh Christopher (2020) The impact of the coronavirus Lockdown on mental health: evidence from the US.

- Hamdan KM, Al-Bashaireh AM, Zahran Z, Al-Daghestani A, AL-Habashneh S, et al. (2021) “University students’ interaction, Internet self-efficacy, self-regulation and satisfaction with online education during pandemic crises of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2)”. International Journal of Educational Management 35: 713-725.

- Al-Balas Mahmoud, Al-Balas Hasan, Ibrahim Jaber, et al. (2020) Distance learning in clinical medical education amid COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan: current situation, challenges, and perspectives. BMC medical education 20: 1-7.

- Donkin Rebecca, Askew Elizabeth, Stevenson Hollie (2019) Video feedback and e-Learning enhances laboratory skills and engagement in medical laboratory science students. BMC medical education 19: 1-12. [crossref]

- Hassan Shahid (2007) How to develop a core curriculum in clinical skills for undergraduate medical teaching in the school of medical sciences at universiti sains malaysia?. The Malaysian journal of medical sciences: MJMS 14: 4-10. [crossref]

- Favarato, Maria Helena, Sarno, Murilo Moura, Peres, Lena Vania Carneiro et al. (2019) Teaching-learning process of clinical skills using simulations-report of experience. MedEdPublish 8.

- O’Doherty D, Lougheed J, Hannigan A, et al. (2019) Internet skills of medical faculty and students: is there a difference?. BMC Med Educ 19: 39.

- Reberti, Ademir Garcia, Monfredini, Nayme Hechem, Ferreira Filho, et al. (2020) Progress Test in Medical School: a Systematic Review of the Literature. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica 44.

- Alsoufi Ahmed, Alsuyihili Ali, Msherghi Ahmed, Elhadi Ahmed, Atiyah Hana, et al. (2020) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education: Medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding electronic learning. PloS one 15: e0242905. [crossref]

- Khalil R, Mansour AE, Fadda WA, et al. (2020) The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Med Educ 20: 285.