Abstract

This study tests the use of specific brief narrative messages that clinicians may use with obese female adolescents regarding body images. The sample comprised 102 obese adolescent females. Each respondent evaluated a unique set of 48 combinations (vignettes) of messages, created from a base size of 36 messages, each set vignettes evaluated by a respondent specified by an underlying experimental design. Regression analysis at the individual respondent level generated coefficients, which were clustered to real three interpretable groups of respondents (viz., three mindsets). These mindsets, limited to the granular topic of body image are: Known need of control (33%), Self-condemnation and shame (46%), Feeling ugly, panicky, and victimized (24%). A subsequent application created a predictive algorithm, a personal viewpoint identifier which is a six-question tool, based on mathematical clustering. The pattern of ratings assigned a new respondent to one of the three mindsets. Clinicians may use effective communication messages by mindset-belonging to influence body image and prevent eating problems in female adolescents.

Introduction

The term body image (BI, hereafter) describes one’s perceptions about one’s own body that develops throughout adolescence [1,2]. Body image entails a perceptual dimension referring to an individual’s self-perception of their appearance and an attitudinal dimension referring to four components: affective, cognitive, behavioural, and satisfaction. The affective component refers to the comprehension of feelings relating to one’s appearance. The cognitive component refers to knowledge about body image. The behavioural component considers body-checking behaviours and actions to avoid situations or objects that evoke body image concerns. The satisfaction component concerns a person’s appreciation over their body as a whole or to specific parts [3].

Female adolescents, more than males, associate higher and increasing Body Mass Index (BMI) with lower self-esteem, routinely evaluate their body, perceive their social worthiness as determined by their physical attractiveness, and tend to obsessively worry about their physical appearance [9,10]. DBI has been associated with low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, poor social functioning, poor health-related quality of life, and concerning unhealthy eating behaviours (i.e., fasting, vomiting, or laxative abuse) leading to malnutrition, noncommunicable diseases, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular incidents and even cancer [4].

Female adolescents stated that DBI is a “touchy subject” [5]. Although clinicians are aware of the importance of communication to promote a positive BI in female adolescents, and 74% of clinicians in a study reported discussing DBI with adolescent patients, 85% of female adolescents reported that they wanted to talk about their DBI with their clinician, but never held such a conversation [2]. Clinicians acknowledge that they feel uncertainty and have no confidence to communicate with female adolescents on DBI [5,6]. Thus, while communication may mitigate the risk factors of DBI, research on how to discuss the topic in practice is scant [2,5]. This study begins to close the gap in the state-of-the-art, exploring preferences of female adolescents regarding clinician-adolescent communication on DBI [5,7,8]. This study seeks to identify and crystalize specific communication messages to support clinicians’ choices of the right messages in communication with adolescents on DBI.

Test Stimuli – Questions, Answers (Elements) and Vignettes

Mind Genomics works by presenting combinations of elements to the respondent, obtaining a rating of the combination, and then deconstructing the rating of the combination to the part-worth contribution of each element. The experimental design uncovers the preference for communication while inhibiting the social desirability bias of respondents as often occurs in surveys. The experimental design approach design has been used to understand preferences in different health contexts [9-11].

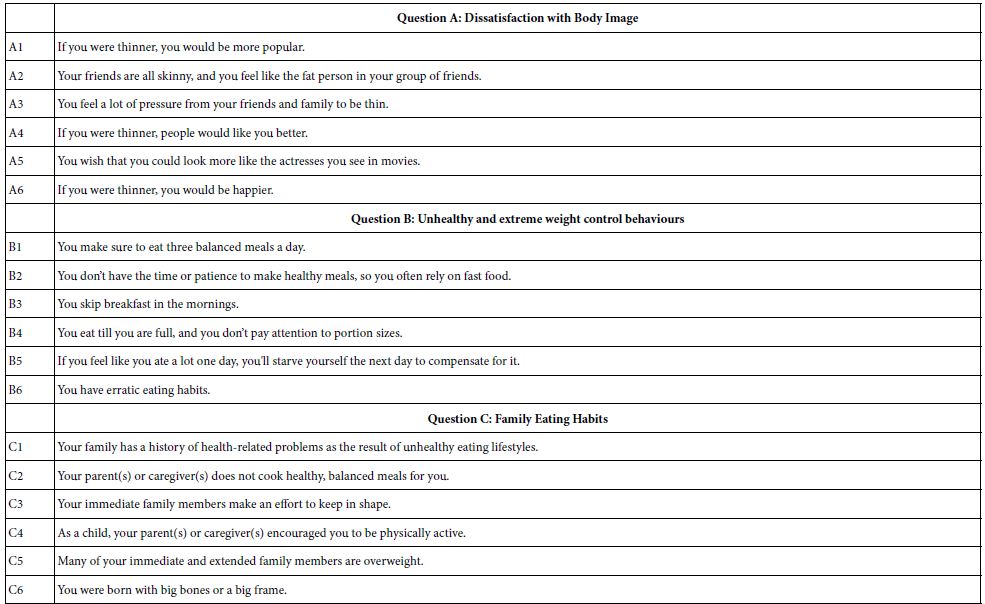

We begin with the raw materials, the elements. Mind Genomics comprises different structures, allowing a flexibility in the research process. The most popular version is the so-called 4×4 design, with four questions, and four answers (elements) for each question. A second popular version is a 6×6 design, entailing six questions, and six answers to each question. This second version, 6×6, was chosen for this study. Table 1 shows the six questions and the 36 elements.

- The independent variables are categories of communication based on previously used scales assessing perceptions regarding DBI [12-14].

- Perceived weight status was assessed with the question: “At this time do you feel that you are..”

- DBI was assessed with a modified version of the Body Shape Satisfaction Scale [15].

- Unhealthy and extreme weight control behaviours included: fasted, ate very little food, used a food substitute (powder or a special drink), and skipped meals [16].

- Binge eating was assessed with questions such as: “You eat so much food that you would feel embarrassed if others saw you” [17].

- Self-weighing was assessed by asking adolescents to indicate how strongly they agreed with the statement, “I weigh myself often.”

Table 1: The six questions (categories), and the six answers to each question

Mind Genomic then combines the elements in vignettes, which for the 6×6 design comprises 48 vignettes three or four elements, respectively. The combinations are not done randomly, but rather constructed according to an underlying experimental design. The design specifies the 48 combinations, ensuring that each element appears equally often, ensures that the 36 elements are statistically independent of each other, and that each respondent evaluates a unique, different set of combinations. This is called a permute experimental design [18]. The permutation allows the researcher to investigate a great of the underlying ‘design space’ of different combinations. Rather than having the researcher somewhat ‘know the promising combination’, the permuted design allows true exploration, even in the total absence of any knowledge. Mind Genomics thus differs from conventional research, sacrificing precision of measurement through replicated measurements of a few test vignettes to precision of understanding of the topic through exploration of much more of the design space. To give an example here, the Mind Genomics effort explored 4896 combinations in the design space rather than exploring 48 vignettes in the design space.

The underlying experimental design serves another purpose as well, specifically Bookkeeping. The experiment design is created so that mutually contradictory elements, viz., elements of the same type but conveying different messages, end up in the same category. The underlying experimental design ensures that a vignette has at most one element or answer from a viz., question. The happy outcome is that the vignettes never present directly contradictory elements to a respondent, at least when one considers a simple reading of the vignette. The elements themselves were relevant to the world of the clinician regarding DBI [19].

Executing the Study on the Internet

Respondents began with an orientation page, signed an informed consent for participation and publication, completed three demographic questions for classification, and finally rated the specific set of 48 combinations of messages corresponding to their own individual experimental design.

The 36 messages were presented in 48 combinations. Every respondent evaluated a unique, different set of 48 combinations [20]. The experimental design varies messages to create different combinations of messages, each combination comprising a minimum of three and a maximum of four messages. The experimental design is set up so that mutually contradictory messages cannot appear together in the same combination. The outcome variable was preferences of adolescent females regarding communication with clinicians on DBI.

It is important to note that the experimental design ensures that the elements will be statistically independent of each other, and the array of 36 elements will allow OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression to estimate the coefficients of the model created for each respondent separately. The rating question was “how important are these vignettes in communication with your clinician on BI?” Each respondent rated the 48 unique combinations using an anchored 9-point scale (1 = “I prefer not to talk about this in communication about my DBI”; 9 = “I would like to talk about this in communication about my DBI”).

After rating the 48 vignettes, the respondent completed a short socio-demographic questionnaire to define aspects of the respondent, without revealing any other personal information. The self-classification question recorded ethnicity and socio-economic status (e.g., higher education level of either parent; family eligibility for public assistance; eligibility for free or reduced-cost school meals, and parental employment status) [16,21].

Data Analysis

The 48 combinations created for each respondent, comprise a stand-alone experimental design for that respondent. Each of the 36 messages is statistically independent of the other 35 messages. The experimental design allows the analysis of the results using OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression, at either the individual respondent level (within-subjects analysis), or the analysis of groups of respondents (OLS) [22].

During the development of Mind Genomics from the 1990’s onwards, it has become a standard practice to convert the Likert Scale to a binary scale, to make the analysis and the interpretations more intuitive. Researchers and especially those who use the data for decisions encounter problems interpreting averages, often asking about the meaning of averages in everyday terms. To simplify the process the Mind Genomics process first transforms the ratings, to move the 9-point scale to a binary, 0/100 scale. By convention, ratings of 1-6 are transformed to 0, ratings of 7-9 are transformed to 100, and then for each newly transformed rating a vanishingly small random number (<10-5) is added.

The foregoing procedure now generates 102 sets of 48 rows each. Each row corresponds to one respondent, and one of the 48 vignettes evaluated by the respondent. The database is set up for OLS regression. The first set of columns record the respondent identification, the order of the vignette (1-48), and one column for each of the information questions asked in the self-profiling classification. The second set of 36 columns are reserved to code the presence of an element in a vignette (coded by the number ‘1’ for the column corresponding to an element), or the absence of an element in a vignette (coded by the number ‘0’). The final set of columns show the rating assigned by the respondent (viz, 1 to 9), and the transformed value of that rating (viz., 0 or 100).

For the OLS analysis, the independent variables are the 36 messages, coded 0 or 1 (absence/presence). The OLS model was formulated as Transformed Binary Rating = k0 + k1 (message A1) + k2 (message A2) … + k36 (message F6). For descriptive purposes, we will look at each of the 37 numbers as a measure of ‘describes me’. The Mind Genomics program computes the additive constant and all 36 coefficients, returning a great deal of data. To uncover patterns, we will present only the positive coefficient > 1. The smaller coefficients will not be shown, even though they were computed. The appropriate cell in the table will be left blank. Furthermore, for strong performing elements, those with coefficients of 8 or higher, the cell will be shaded to drawn attention to these elements.

The additive constant of the OLS model is a baseline, an estimated parameter, providing a measure of how likely it is for an adolescent to say ‘this describes the way I would like to talk to my clinician’, albeit in the absence of messages. Of course, the underlying experiment design ensures that every vignette comprises 3-4 elements, so the additive constant, is a baseline, a strictly estimated parameter.

The individual coefficients show the driving power of the messages. Continuing with the example but moving to the coefficient, a positive number of +8, means that when the message is incorporated into the combination, an additional 8% of the respondents are likely, on average, to say that they ‘this describes the way I would like to talk to my clinician.

People differ in their attitudes and perceptions, as well as their needs and wants. The self-profiling classification allows the creation of equations either for the Total Panel, or for any specified group. The OLS regression simply calculates the additive constant and the 36 coefficients based upon all the data appropriate to define that subgroup.

Finally, person-to-person variation may not necessarily depend on who the person is or what a person ‘believes’ for a specific situation. One’s perceptions and values may not clearly co-vary with who a person IS, or how a person THINKS about a general problem. There may be groups of people who are similar, not necessarily for all of the topics of their lives, but perhaps only for the granular topic being investigated. These are mindsets, groups of people who are similar in a specific topic area, based upon the similar of the pattern of their coefficients, in this case their 36 coefficients. To discover these groups, so-called ‘mindsets’, requires the use of a simple clustering method (viz., k-means). The clustering applied to the patterns of coefficient reveals new-to-the-world groups of individuals showing similar patterns of preferences in communications, a way to understand the different needs of the groups. [23].

Sample

Respondents were 102 obese female adolescents from the greater New York area, ages 13-19 years old. Respondents gave their informed consent for participation and publication. The size of the sample is consistent with the suggested sample size in conjoint analysis studies, particularly when aiming at stability of coefficients rather than stability of means [24]. Since DBI entails both a physiological indicator (BMI) and a subjective construct of BI, inclusion criteria for the study were a BMI of 30 and above and respondents’ self-definition of themselves as being overweight.

Relating the Presence/Absence of the Elements to the Binary Transformed Rating

The heart of the Mind Genomics analysis is the set of coefficients emerging from the regression analysis. Recall that the OLS regression deconstructs the response to the vignettes into the part-worth contribution of the 36 elements. Respondents cannot ‘game’ the system and give the correct analysis, simply because in the rapid process of stimulus/response, the typical evaluation time is about 3-4 seconds. There is simply no time for the respondent to try to ‘guess’ the right answer. It is simply impossible to do. Respondents report that they simply look at the vignette, and assign a value, often stating that they feel that they are guessing.

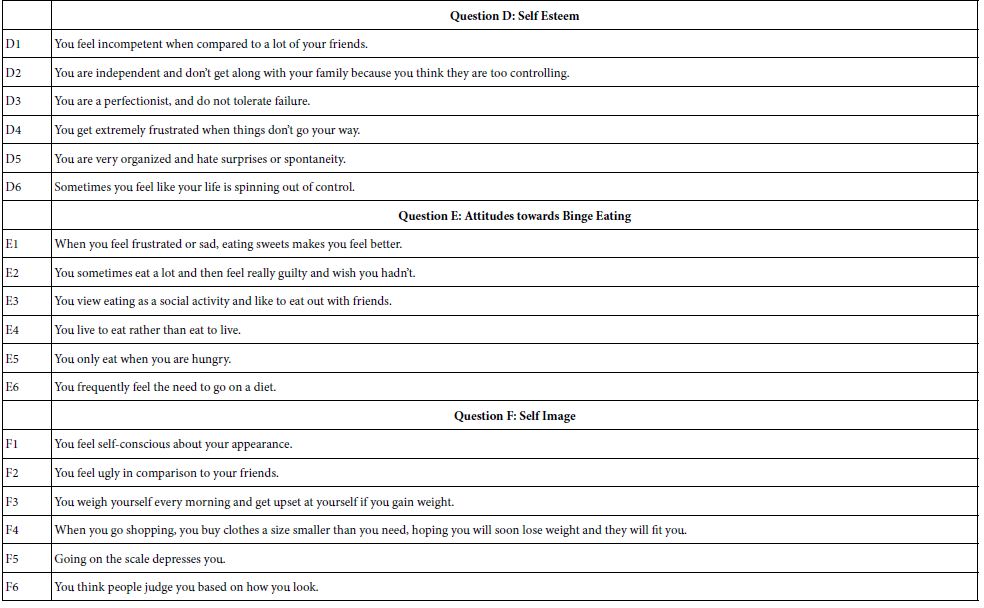

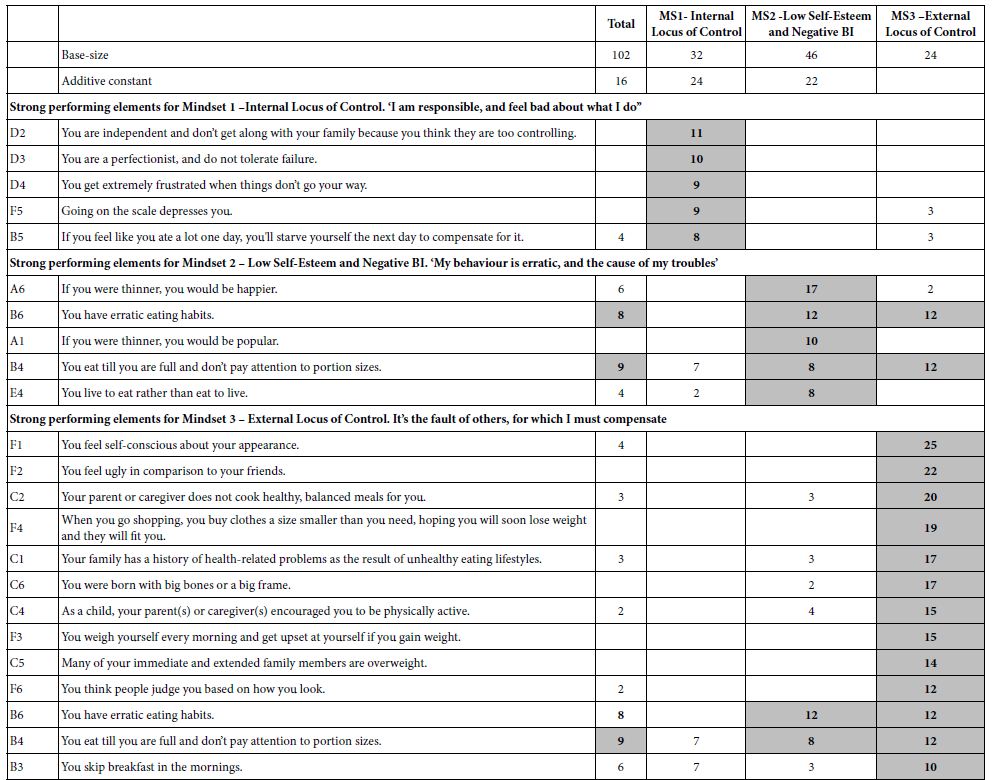

Table 2 presents the regression coefficients for the total panel and for the three mindsets as created by k-means clustering analysis. Messages are sorted by the strong performing coefficients for the three mindsets. The same message may appear twice when it is a strong performer. The total panel shows only two strong performing messages. These are “You eat until you are full and don’t pay attention to portion sizes”; and “You have erratic eating habits” reflecting erratic eating habits. It is when the data from the three mindsets are laid out that the patterns emerge.

Table 2: Coefficients for the messages by Total Panel and by the three emergent only positive coefficients greater than +1 are shown to allow patterns to emerge. The table shows strong performers for each mindset. (MS).

Table 2 suggests that a seemingly flat pattern of coefficients from the total panel may result from the combination of groups of adolescent females with different, often opposite, points of view. Groups of adolescents with similar response patterns emerge from the patterns in the data, patterns which are interpretable and parsimonious. What members of one mindset prefer to discuss in communication with clinicians on DBI may be irrelevant to adolescents in other mindsets. Furthermore, the coefficients for the mindsets are much higher, suggesting that the results from the total panel hide the underlying narratives by averaging dramatically different subgroups with different ways of thinking about their preferences. K-means clustering shows that there are distinct groups with different points of view regarding communication on DBI.

The Distribution of Mindsets across the Population

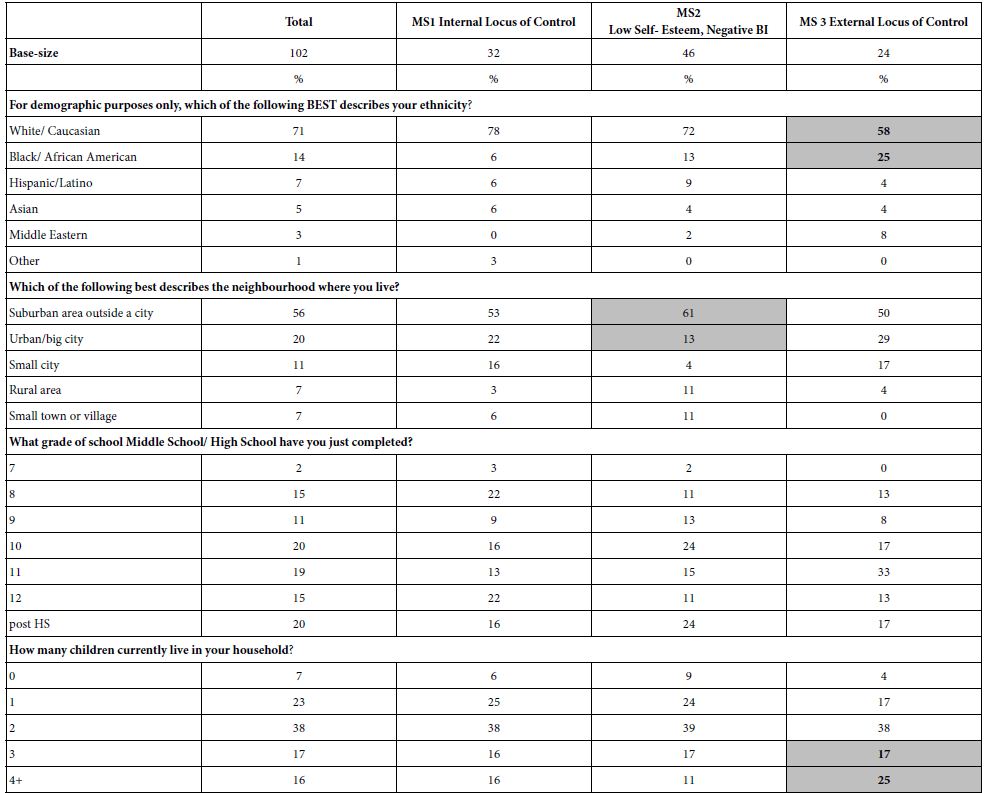

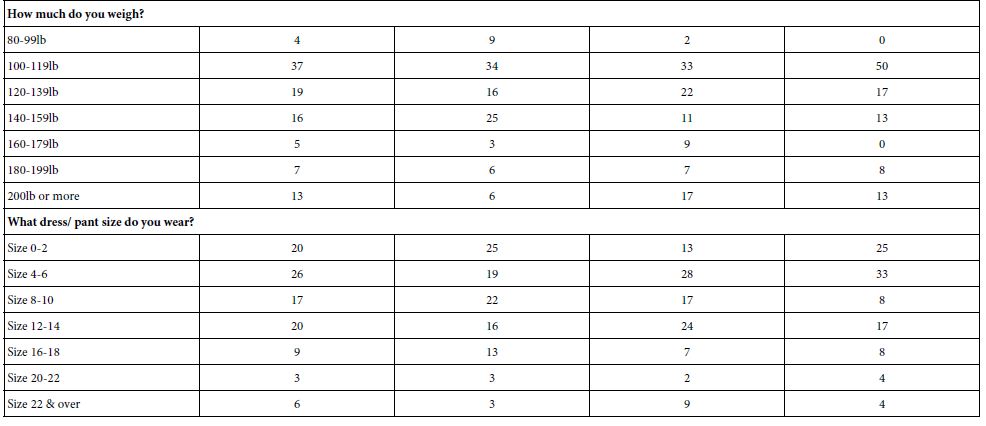

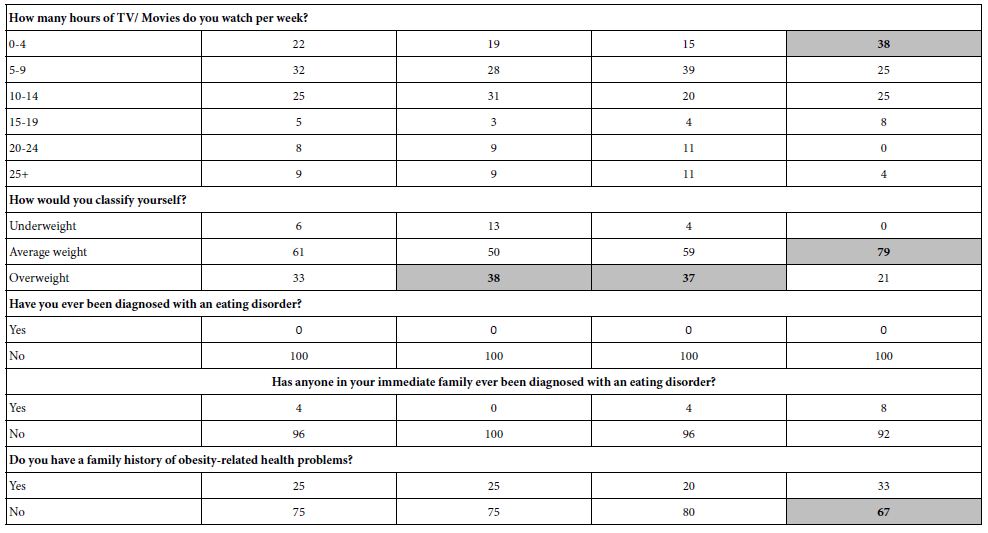

Table 3 shows that the three mindsets are distributed similarly across demographic attributes of the female adolescents, whether those are geo-demographics, parent’s education, or actual weight. There are some departures from random distribution, but there is no clear pattern and no explanations for the departures. Most of the adolescents are either Caucasian or African American. Mindset 2 seems to include more respondents who live in the suburbs. Mindset 3 comprises more African Americans and is over-represented by those with large families. Its members feel ugly, panicky, and a victim.

Table 3: Distribution of respondents into different groups, for Total Panel and for the three emergent min-sets

Assigning an Adolescent to a Mindset

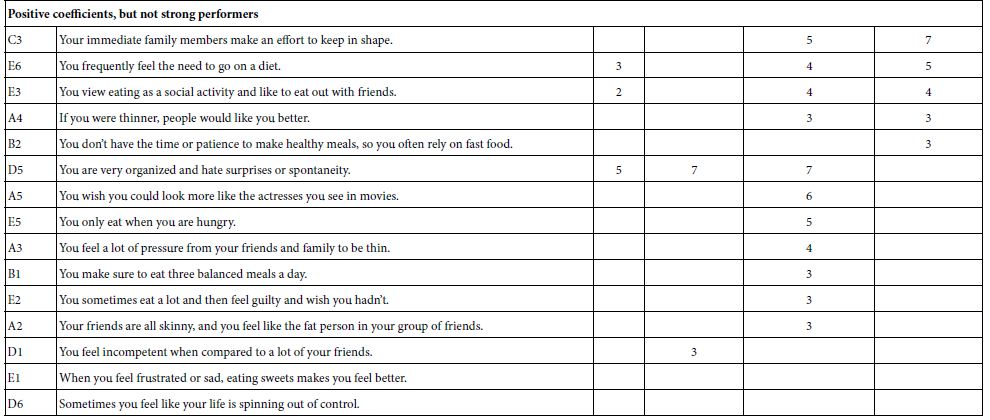

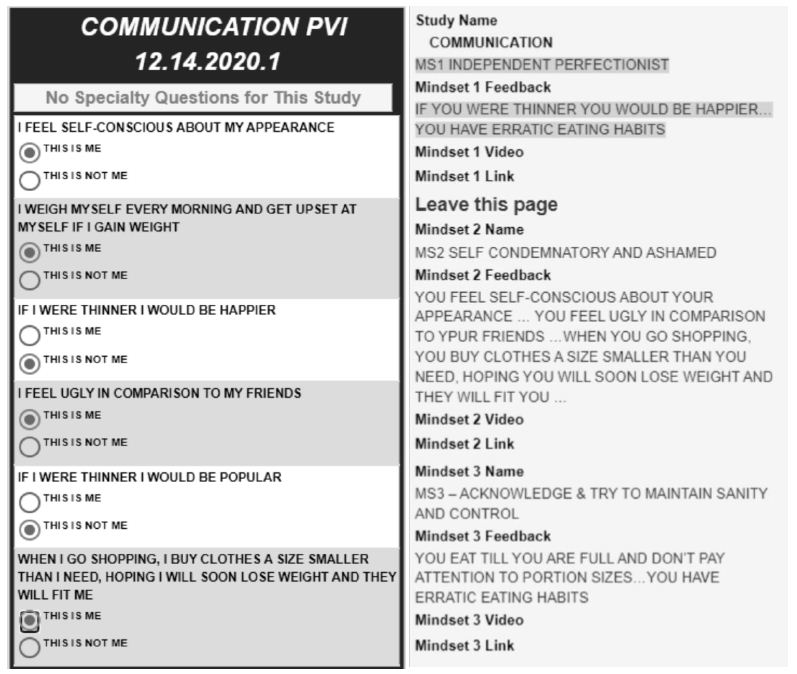

This study reveals the existence of mindsets in the population of adolescent females and provides an organizing principle for clinicians by which to choose messages on DBI in communication with adolescents. For the data to become ‘actionable,’ it is necessary to develop an easy-to-use a predictive algorithm to rapidly assign an adolescent in the clinic to one of the three sample mindsets. Using a Monte-Carlo simulation process, we created a Personal Viewpoint Identifier (PVI) based on the mindsets data (Table 2). The PVI identifies a set of six original messages which can be scored on a two-point scale. Each of the 64 patterns of responses to messages assigns an adolescent to one of the three mindsets. The PVI presents the algorithm showing the six distinguishing messages taken from the data in Table 2. The pattern of response to those six messages assigns a female adolescent to a specific mindset, and may be linked to a video, to a website, or simply to the clinician.

Figure 1 presents the PVI which can be found at: https://www.pvi360.com/TypingToolPage.aspx?projectid=1266&userid=2008. The left panel shows the PVI instrument, and the completed answers from one person. The right panel shows the three mindsets. The shaded text presents the mindset to which the person is assigned. The tool is designed to be used in clinical work, as well as on the internet.

Figure 1: The PVI which can be found

Discussion and Conclusions

This experimental design explored preferences of adolescent females regarding communication messages with clinicians on their DBI. The current study appears to be the first one to investigate preferences of adolescents regarding communication with clinicians on DBI. Within that framework, the study reveals the potential of tailoring, possibly enhancing the communication based upon the uncovered preference patterns of mindsets. The study revealed three mindsets, a finding which provides deeper insight to the minds of the adolescent.

Adolescents belonging to Mindset 1 (31%) seem to have an internal locus of control and prefer communication messages which accord with, and which encourage their internal locus of control [25]. They prefer to feel that they, not society nor their parents, have the control to change their thinking and behaviours, with the clinician by their side. They prefer communication which focuses on their responsibility and choices regarding DBI. For example, a potentially acceptable phrase might be: “You are independent and don’t get along with your family because you think they are too controlling”. Effective communication messages for members of Mindset 1 should focus on providing them with a higher sense of control through higher awareness of their feelings about their weight and behaviours due to their DBI, messages focusing on the possible reduction of their health-related quality of life [26].

Adolescents belonging to Mindset 2, comprising almost half of the population (45%), are female adolescents with low self-esteem and a negative BI increasing the risk for eating disorders [15]. Members of Mindset 2 prefer communication which encourages their reflective thinking:” Do you think that if you were thinner, you would be happier”; “Do you think that if you were thinner, you would be popular?” This finding confirms previous findings regarding adolescents’ expectations that the communication with clinicians will tap into mental and emotional aspects of DBI [34]. It also supports suggestions to convey genuine caring, active listening, and compassion to facilitate communication on DBI [27,28].

Adolescents belonging to Mindset 3, the smallest group (24%), appear to have a strong external locus of control. They feel they are victims of circumstances that are beyond their control [25]. They internalize the opinion of others, and in turn judge themselves [29]. This finding is in line with a study that contended that obesity should be communicated as driven by a psychological cause rather than a behavioural cause to mitigate prejudice and stigma [30]. Mindset 3 responds positively to the following communication messages: “You feel self-conscious about your appearance”; “You feel ugly in comparison to your friends”; “Your parent or caregiver does not cook healthy, balanced meals for you”; “When you go shopping, you buy clothes a size smaller than you really need, hoping that you will soon lose weight and they will fit you”; “You were born with big bones or a big frame”; “Your family has a history of health-related problems as the result of unhealthy eating lifestyles”. Communication with members of Mindset 3 should provide a sense of order, highlight dangers of unhealthy weight control behaviours, and enhance their internal locus of control [25,31]. Members of Mindset 3 respond when they sense that the communication with clinicians on DBI will be supportive, engaging, empathic, and authentic, indicating that the clinician cares about them as an individual [5].

This study has several contributions. Theoretically, the study extends the existent knowledge revealing preferences of obese female adolescents in sensitive communication with clinicians regarding their dissatisfaction with body image. The data suggest at least three mindsets of adolescents, showing the pattern of distinct preferences of adolescents in each mindset for specific communication messages of clinicians about DBI. Methodologically, the experimental design overcomes typical biases of survey questionnaires enabling to test many combinations of messages reflecting our complex reality [33].

In terms of practice contribution, this study developed a predictive algorithm enabling clinicians to quicky assign adolescent females in the clinic to a mindset in the sample, supporting clinicians in their communication on DBI with female adolescents in the clinic. Set-tailored communication messages may be helpful from a therapeutic standpoint to build trust of adolescents in the clinician, promoting adolescents’ perseverance throughout change processes [34]. Mindset-tailored communication may mitigate DBI among obese female adolescents, through trust in the clinician, perhaps preventing future disordered eating behaviours and extreme weight control behaviours [5]. Communication messages should correspond to the preferences of adolescents by mindset membership.

Currently, clinicians may discuss clinical issues with adolescent females (i.e., weight, growth, nutrition), but patient-centred communication on DBI requires clinicians to meet the communication preferences of the female adolescent and understand what troubles her. Currently, communication on DBI is sub-optimal as clinicians are not trained at patient-centred communication, facilitating trust, and open communication on DBI [5]. Female adolescents judge the communication with clinicians by the clinician’s communication skills, the extent of interest of the clinician in them as individuals, and the extent of sensitivity in discussing DBI [34,35]. Therefore, it may be helpful for if clinicians could customize the communication according to their mindset-membership. The creation of a predictive algorithm enables clinicians to better understand the adolescent and promote a positive BI through mindset-tailored communication messages. The ability of clinicians to tailor the communication to the mindset-belonging of an adolescent, almost at the start of the relationship, provides new opportunities for interactions which may improve trust in the communication on DBI and promote health, wellbeing, and life satisfaction. Last, our findings reaffirm the need to train clinicians to raise their awareness of differences among female adolescents on communication preferences and psychosocial issues associated with DBI [17]. Clinicians should set communication goals in mind (providing information, reducing distress, increasing adolescent satisfaction, and encouraging hope) while prioritizing efforts to reduce distress [36].

References

- Alharballeh S, Dodeen H (2021) Prevalence of body image dissatisfaction among youth in the United Arab Emirates: gender, age, and body mass index differences. Current Psychology 1-10. [crossref]

- Hartman-Munick SM, Gordon AR, Guss C (2020) Adolescent body image: influencing factors and the clinician’s role. Current Opinion in Paediatrics’ 32: 455-460. [crossref]

- Smolak L (2012) Appearance in childhood and adolescence. The Oxford handbook of the psychology of appearance 123-141.

- Duarte C, Gilbert P, Stalker C, Catarino F, Basran, J, et al. (2021) Effect of adding a compassion-focused intervention on emotion, eating and weight outcomes in a commercial weight management programme. Journal of health psychology 26: 1700-1715. [crossref]

- Helms SW, Christon LM, Dellon EP, Prinstein MJ (2017) Patient and provider perspectives on communication about body image with adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Paediatric Psychology 42: 1040-1050. [crossref]

- Bodner ME, Bilheimer A, Gao X, Lyna P, Alexander SC, et al. (2017) Studying physician-adolescent patient communication in community-based practices: recruitment challenges and solutions. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health 29. [crossref]

- Gabay G, Tarabeih M (2020) “A Bridge Over Troubled Water”: Nurses’ Leadership in Establishing Young Adults’ Trust Upon the Transition to Adult Renal-Care-A Dual-Perspective Qualitative Study. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 53: e41-e48. [crossref]

- Foti K, Lowry R (2010) Trends in perceived overweight status among overweight and non overweight adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 164: 636-642. [crossref]

- Gabay G, Moskowitz H, Kochman M (2015) Market sensing, mind genomics and Health promotion. Business Expert Press 142-157.

- Gabay G, Moskowitz HR (2015) Mind genomics: what professional conduct enhances the emotional wellbeing of teens at the hospital? Journal of Psychological Abnormalities 4: 1000147.

- Gabay G, Ornoy H, Moskowitz H (2022) Patient-centered care in telemedicine–An experimental-design study. International Journal of Medical Informatics 159: 104672. [crossref]

- Gunnard K, Krug I, Jiménez‐Murcia S, Penelo E, Granero R, et al. (2012) Relevance of social and self‐standards in eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review 20: 271-278. [crossref]

- Bachar E, Gur E, Canetti L, Berry E, Stein D (2010) Selflessness and perfectionism as predictors of pathological eating attitudes and disorders: A longitudinal study. European Eating Disorders Review 18: 496-506. [crossref]

- Haines J, Kleinman KP, Rifas-Shiman SL, Field AE, Austin SB (2010) Examination of shared risk and protective factors for overweight and disordered eating among adolescents. Archives of Paediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 164: 336-343. [crossref]

- Pingitore R, Spring B, Garfieldt D (1997) Gender differences in body satisfaction. Obesity Research 5: 402-409. [crossref]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall MM, Larson N, Story M, Fulkerson JA, et al. (2012) Secular trends in weight status and weight-related attitudes and behaviors in adolescents from 1999 to 2010. Preventive Medicine 54: 77-81. [crossref]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Falkner N, Story M, Perry C, Hannan PJ, et al. (2002) Weight-teasing among adolescents: correlations with weight status and disordered eating behaviors. International Journal of Obesity 26: 123-131. [crossref]

- Gofman A, Moskowitz HR, Mets T (2010) Accelerating structured consumer‐driven package design. Journal of Consumer Marketing 27: 157-168.

- Moskowitz HR (2012) ‘Mind genomics’: The experimental, inductive science of the ordinary, and its application to aspects of food and feeding. Physiology & Behavior 107: 606-613. [crossref]

- Porretta S, Gere A, Radványi D, Moskowitz H (2019) Mind Genomics (Conjoint Analysis): The new concept research in the analysis of consumer behaviour and choice. Trends in Food Science & Technology 84: 29-33.

- Graybill FA, Iye HK (1994) Regression analysis: concepts and applications.

- Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J (2009) The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference, and prediction. Springer series in statistics. Springer New York.

- Haxby JV, Gobbini MI, Furey ML, Ishai A, Schouten JL, et al. (2001) Distributed and overlapping representations of faces and objects in ventral temporal cortex. Science 293: 2425-2430. [crossref]

- Cattin P, Wittink DR (1982) Commercial use of conjoint analysis: A survey. Journal of Marketing 46: 44-53.

- Gabay G (2015) Perceived control over health, communication and patient–physician trust. Patient Education and Counselling 98: 1550-1557. [crossref]

- Chen G, He J, Zhang B, Fan X (2022) Body weight and body dissatisfaction among Chinese adolescents: Mediating and moderating roles of weight-related teasing. Current Psychology 41: 298-306.

- Zhou Y, Acevedo Callejas ML, Li Y, MacGeorge EL (2021) What Does Patient-Centred Communication Look Like? Linguistic Markers of Provider Compassionate Care and Shared Decision-Making and Their Impacts on Patient Outcomes. Health Communication 1-11. [crossref]

- Gorman JR, Drizin JH, Smith E, Flores-Sanchez Y, Harvey SM (2021) Patient-centered communication to address young adult breast cancer survivors’ reproductive and sexual health concerns. Health Communication 36: 1743-1758. [crossref]

- Volkmann NM, de Castro TG (2021) Body dissatisfaction, rumination and attentional disengagement toward computer-generated bodies. Current Psychology 1-9.

- Khan SS, Tarrant M, Weston D, Shah P, Farrow C (2018) Can raising awareness about the psychological causes of obesity reduce obesity stigma? Health Communication 33: 585-592. [crossref]

- Gabay G (2016) Exploring perceived control and self-rated health in re-admissions among younger adults: A retrospective study. Patient Education and Counselling 99: 800-806. [crossref]

- Zuair AA, Sopory P (2022) Effects of media health literacy school-based interventions on adolescents’ body image concerns, eating concerns, and thin-internalization attitudes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Communication 37: 20-28. [crossref]

- Gustafsson A, Herrmann A, Huber F (2007) 1 Conjoint Analysis as an Instrument of Market. Conjoint Measurement: Methods and Applications, 1.

- Swedlund MP, Schumacher JB, Young HN, Cox ED (2012) Effect of communication style and physician–family relationships on satisfaction with pediatric chronic disease care. Health Communication 27: 498-505. [crossref]

- Aboueid S, Ahmed R, Jasinska M, Pouliot C, Hermosura BJ, et al. (2022) Weight Communication: How Do Health Professionals Communicate about Weight with Their Patients in Primary Care Settings? Health Communication 37: 561-567. [crossref]

- Hua J, Howell JL, Sweeny K, Andrews SE (2021) Outcomes of physicians’ communication goals during patient interactions. Health Communication 36: 847-855. [crossref]