Abstract

Especially since the recent atrocities in Ukraine and Iran, but also in Syria and China, the close interaction between psychological recovery of survivors, and efforts to investigate and prosecute severe human rights violations has become an issue of concern. Investigations and the collection of evidence, especially witness statements, are conducted by national and international authorities, including international courts, but also by NGOs and journalists. While preservation of evidence, that should be guided by the relevant UN/WMA standard, the “Istanbul Protocol” and witness statements, are an important and necessary part of such investigations, the protection of already psychologically distressed or even traumatized victims against suffering and traumatizing interviews or re-traumatization has become a concern in international, such as EU, standards, and is also mentioned in the Istanbul Protocol as reference standard, but without giving sufficient concrete guidance. Mental health is an important part in this process, as outlined in this article. An interdisciplinary working group of the World Psychiatric Association Scientific Section on Psychological Consequences of Persecution and Torture has developed and tested a new standard protocol that is recommended to be used when interviewing survivors of extreme human rights violations to address this concerns, especially in the context of the important global efforts to involve direct and indirect victims such as family members in collecting evidence as important first step in identifying, documenting, investigating and prosecuting such crimes.

Keywords

Human rights, Torture, Genocide, War, Therapeutic justice, Psychology, Victims

Human rights violations, and especially those usual described as “extreme violations” such as torture, war crimes, or genocidal actions, are not only destructive to societies, but also have been demonstrated to have severe, often lifelong impact on the mental health of individuals and communities, including transgenerational trauma transmission [1] and epigenetic sequels [2-4]. They must be seen as the probably at present most severe challenges to public mental health [5,6]. New and usually interdisciplinary strategies and interventions targeting not only individuals but communities and societies at large, might have to be developed and implemented, usually in the context of the general mental health and psychosocial services (MHPSS) approach [7,8] recommended by the UN and WHO. In spite of the development of a number of international legal and humanitarian treaty systems and instruments in humanitarian and human rights law, and of monitoring institutions such as the office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, of International Criminal courts, and of offices of the UN special rapporteurs on subjects like torture, on the rights of women and children, and on genocide, the impunity of perpetrators is still a major challenge so far not sufficiently addressed in an effective way in national or international courts, except in a few exceptional cases. This means not only that the risk of future violations by the same or other perpetrators or countries must be expected to increase, but also that the suffering of victims will continue or even increase [9,10]. New strategies like the application of the legal principle of Universal Jurisdiction [11], that permits countries to prosecute, arrest and put on trial perpetrators of such extreme violations like torture or other crimes under international law, have been implemented in countries such as Germany, Austria, and France, yielding first results and conviction of some perpetrators. This must be seen as an important tool in the unfortunately common situation, that an efficient investigation and fair legal process is not possible in the country of origin of the victims who are escaping to safer third countries such as EU countries or the United States. Evidence is a strong element necessary in this process [12].

One of the key areas identified in this context, is that of an interdisciplinary approach in the collection of evidence and in the psychological support off survivors and witnesses, who must be expected to suffer by re confrontation with highly traumatic memories during witness statements, medical examination [13], and during the court hearings.

Medical evidence, including especially also psychological evidence, can play an important role in this context, and international standards such as the Minnesota protocol [14] and the recently updated Istanbul protocol (Manual on Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment) [15,16] have been developed and are supported by the United Nations and other international bodies and organisations to ensure proper procedures in examining victims and survivors. The Istanbul protocol also underlines the importance of protecting survivors during examination and during and after the witnessing and investigation process against undue distress and secondary victimisation or re-traumatization by the necessary legal interventions. In a similar way, standards by the European Union (mostly framework directives influencing the legal process in all EU countries), such as the reception guidelines for refugees or the “minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime”, have initiated a paradigm shift to underline the importance of such psychological support and protection against secondary trauma in the necessary legal procedures besides legal recommendations.

The EU … states in article 9 of the “crime victims” directive that:

“victims of crime should be protected from secondary and repeat victimisation, from intimidation and from retaliation, should receive appropriate support to facilitate their recovery and should be provided with sufficient access to justice”.

In this context, a number of projects have demonstrated, that giving testimony about human rights violations in an adequate setting can be as or even more important than established medical treatment models or that giving testimony can improve their impact. A probably first example was the “testimony therapy” approach developed in Latin America [17,18] when a legal fight against impunity was impossible during total social control by local dictatorships. Creating a testimony or witness statement against perpetrators of torture by survivors became a key element of this special form of psychotherapy and has inspired also other new treatment approaches [19]. This is an insight that is also used on the level of communities and societies as part of a transitional justice process, for example in so-called truth and reconciliation commissions in South Africa or Rwanda [20-23], though results appear to be not always satisfactory. The discussion compares here the concepts of “restorative” vs. “punitive” justice, but in any case, impunity of perpetrators must be seen as a major challenge to survivors’ psychological health and wellbeing in whatever setting [9]. The EU Network for investigation and prosecution of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes (The Genocide Network), Eurojust and the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court published on 21 September 2023 guidelines for civil society organisations, which seek to collect and preserve information to contribute to investigations and prosecutions at national level or before the ICC on “Documenting international crimes and human rights violations for accountability purposes”.

A necessary conclusion in this context is, that giving witness statements and evidence for example in proper medical examination and court testimony can be an important part of recovery and healing for survivors and witnesses [21], in addition to supporting the legal process.

Unfortunately, neither the before mentioned standard examination protocols, nor the support of survivors of extreme violence are sufficiently covered by most medical curricula.

The interdisciplinary team of the World Psychiatric Association Scientific Section on Psychological Consequences of Persecution and Torture have therefore developed a training programme and protocol to improve the psychological aspects of evidence collection and to protect witnesses and survivors during the legal process or investigation.

The protocol was applied, tested, and modified as part of a project supported by the UN Voluntary Fund for the Victims of Torture, with survivors of human rights violations from Syria and to Ukraine, in collaboration with legal NGOs active in this process and with the WPA section since 2018.

We developed a protocol focusing on the specific steps of the medical accompaniment and required psycho-social support in the context of collecting evidence and testimonies of international crimes and severe human rights violations based on our work experiences and research. In the following part of this article, we want to present this protocol for discussion and dissemination in the international medical and legal communities, considering especially the possible use in the recently started process of universal jurisdiction, International Criminal courts and the collection of evidence for example in Syria and the Ukraine. The protocol also underlines and is referring to the afore- mentioned Istanbul protocol of the United Nations and the World Medical Association, [15,16,24] and is to be seen as supporting, and not replacing this important standard, focusing on the psychological and mental health aspects of examination, witnessing and witness support.

This last aspect is important, but often neglected in forensic settings in the interaction with survivors and witnesses, who can be seen also as indirect victims, probably due to the historical focus of the forensic sciences either on the bodies, or in forensic mental health on evaluation of perpetrators, or on the evaluation of competence.

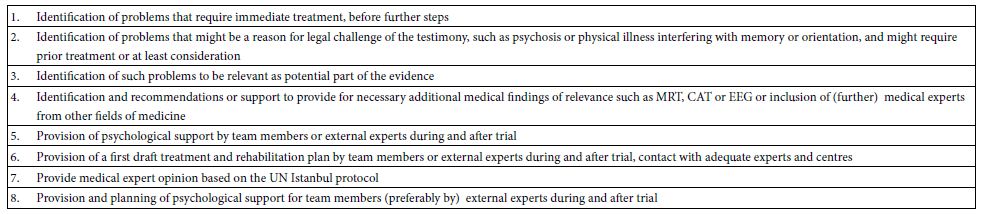

We see a psychological and/or psychiatric examination as an integral and important part of the above legal process, keeping in mind that this has to consider the stigma against mental health and the possible distress by survivors during re confrontation with traumatic memories, as also culture specific issues such as cultural idioms of distress, that can be part of the evidence [25-27]. We have summarized the key points on the importance of mental health assessment in Table 1.

Table 1: Summary: Relevance of mental health in the examination of witnesses of crimes

Guideline and Protocol

The WPA section therefore recommends the following steps:

(Note: For the following process, we recommend an interdisciplinary approach, and installation of a well experienced and trained team)

- Preparation of the case. All evidence available should be collected, and translated by lawyers, and for medical findings by the medical team (Medteam). The Medteam will analyse medical data to identify issues as mentioned in attachment I (note: here: Table 1) and familiarize team members with history and experience of the survivor/witness, in order to better prepare for testimony and examination and avoid repetition of details in the examination, to consult with experts knowledgeable of the situation and of transcultural issues, to identify experts or translators to be added to the process. The team leaders will offer legal and psychological training of the legal and medical team, including in the Istanbul Protocol.

- Preparatory contact with witness, to present the team, build trust and confidence and the approach in the protocol, identify further issues as in table/attachment, agree on procedures with client, reduce stigma anxiety, provide support to locate and bring medical and other documentation, answer questions in regard to treatment and legal framework

- Conduct “Welcome” meeting with support team on arrival for court hearing, psychological preparation and further rapport and trust building, if necessary or adequate in the process, medical or diagnostic interventions.

- Offer support during hearings by legal, medical and psychological team members, and if necessary, organize immediate crisis intervention and medical treatment, including interventions to reduce distress. If required they will also provide advice or specific expertise to the court.

- Debriefing and measures for stress reduction and relieve immediately after testimony will be offered

- Follow up support including psychosocial support (following the Interagency Standing Committee (IASC) mental health and psychosocial services (MHPSS) model [28,29], provision or organization of medical support, and of further expertise as required by court, team or survivor/witness, including contact with local specialized service institutions.

Summary

Providing for mental health aspects in interacting with witnesses of human rights violations is important not only for supporting evidence collection and aiding investigation and prosecution by lawyers, but also addresses the necessary protection of often psychologically severely traumatized, vulnerable and suffering survivors and witnesses. The guideline/protocol offers concrete advice in protecting witnesses during necessary interviews and examinations, as outlined by the UN Istanbul Protocol. This approach has become even more important in the context of present wide spread violations of international humanitarian and human rights laws in Ukraine, Syria and other countries.

References

- Kizilhan JI, Noll-Hussong M, Wenzel T (2021) Transgenerational Transmission of Trauma across Three Generations of Alevi Kurds. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19. [crossref]

- Kellermann NP (2013) Epigenetic transmission of Holocaust trauma: can nightmares be inherited? Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 50: 33-39. [crossref]

- Vukojevic V, Kolassa IT, Fastenrath M, Gschwind L, Spalek K, et al. (2014) Epigenetic modification of the glucocorticoid receptor gene is linked to traumatic memory and post-traumatic stress disorder risk in genocide survivors. J Neurosci 34: 10274-10284. [crossref]

- Yehuda R, Daskalakis NP, Lehrner A, Desarnaud F, Bader HN, et al. (2014) Influences of maternal and paternal PTSD on epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in Holocaust survivor offspring. Am J Psychiatry 171: 872-880. [crossref]

- Wenzel T, Kienzler H, Wollmann A (2015) Facing Violence – A Global Challenge. Psychiatr Clin North Am 38: 529-542. [crossref]

- Wenzel T, Schouler-Ocak M, Stompe T (2021) Editorial: Long Term Impact of War, Civil War and Persecution in Civilian Populations. Front Psychiatry 12: 733493. [crossref]

- Duckers M, van Hoof W, Willems A, Te Brake H (2022) Appraising Evidence-Based Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) Guidelines-PART II: A Content Analysis with Implications for Disaster Risk Reduction. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19. [crossref]

- Te Brake H, Willems A, Steen C, Duckers M (2022) Appraising Evidence-Based Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) Guidelines-PART I: A Systematic Review on Methodological Quality Using AGREE-HS. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19. [crossref]

- Williams S (1999) Violence against women. Ending impunity for sexual violence. Links (Oxford) 1-2. [crossref]

- Zawati HM (2007) Impunity or immunity: wartime male rape and sexual torture as a crime against humanity. Torture 17: 27-47. [crossref]

- Macedo S (2004) Universal jurisdiction: national courts and the prosecution of serious crimes under international law. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Gallagher K (2009) Universal Jurisdiction in Practice: Efforts to Hold Donald Rumsfeld and Other High-level United States Officials Accountable for Torture. Journal of International Criminal Justice 7: 1087-1116.

- Bruin Re, Reneman M, Bloemen E (2006) Care full: medico-legal reports and the Istanbul Protocol in asylum procedures. Pharos.

- Keten A (2020) Minnesota Autopsy Protocol. J Forensic Leg Med 72: 101944.

- Iacopino V, Haar RJ, Heisler M, Lin J, Fincanci SK, et al. (2022) Istanbul Protocol 2022 empowers health professionals to end torture. Lancet 400: 143-145. [crossref]

- Koseoglu Z (2022) Launch of the revised version on the Istanbul Protocol. Torture 32: 89. [crossref]

- Pakman M (2004) The epistemology of witnessing: memory, testimony, and ethics in family therapy. Fam Process 43: 265-274. [crossref]

- van Dijk JA, Schoutrop MJ, Spinhoven P (2003) Testimony therapy: treatment method for traumatized victims of organized violence. Am J Psychother 57: 361-373. [crossref]

- Kizilhan JI, Neumann J (2020) The Significance of Justice in the Psychotherapeutic Treatment of Traumatized People After War and Crises. Front Psychiatry 11: 540. [crossref]

- Kaminer D, Stein DJ, Mbanga I, Zungu-Dirwayi N (2001) The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa: relation to psychiatric status and forgiveness among survivors of human rights abuses. Br J Psychiatry 178: 373-377. [crossref]

- Stein DJ, Seedat S, Kaminer D, Moomal H, Herman A, et al. (2008) The impact of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on psychological distress and forgiveness in South Africa. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 43: 462-468. [crossref]

- Swartz L, Drennan G (2000) The cultural construction of healing in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission: implications for mental health practice. Ethn Health 5: 205-213. [crossref]

- Taylor L (2022) Colombia’s truth commission reveals the devastating health impact of half a century of conflict. BMJ 378: o2023. [crossref]

- Keten A, Nicolakis J, Abaci R, Lale A (2022) An Evaluation within the Context of the Istanbul Protocol of the Medico-Legal Examinations of Turkish Detainees during the Recent State of Emergency in Turkey. J Law Med 29: 254-259. [crossref]

- Cork C, Kaiser BN, White RG (2019) The integration of idioms of distress into mental health assessments and interventions: a systematic review. Glob Ment Health (Camb) 6: e7. [crossref]

- Jacob KS (2019) Idioms of distress, mental symptoms, syndromes, disorders and transdiagnostic approaches. Asian J Psychiatr 46: 7-8. [crossref]

- Kaiser BN, Jo Weaver L (2019) Culture-bound syndromes, idioms of distress, and cultural concepts of distress: New directions for an old concept in psychological anthropology. Transcult Psychiatry 56: 589-598. [crossref]

- Marshall C (2022) The inter-agency standing committee (IASC) guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) in emergency settings: a critique. Int Rev Psychiatry 34: 604-612. [crossref]

- O’Callaghan P (2014) Case study: ten lessons learned while carrying out a MHPSS intervention with war-affected children in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2011. Int J Emerg Ment Health 16: 241-245. [crossref]