Abstract

Introduction: Chyloperitoneum is defined as the presence of lymph of thoracic or intestinal origin in the abdominal cavity. It is reported infrequently and is a rare manifestation of multiple deseases. Most of the cases are secondary and are associated with direct trauma to the peritoneal dialysis. Renal replacement therapy is necessary in up to 10% of children who undergo cardiac surgery with extracorporeal circulation, indicated in cases of water overload, acute renal dysfunction or ionic alterations.

Objective: To report the case of a 15-day-old newborn, operated on for Transposition of the Great Vessels, who presented as a postoperative complication, dicharge of chylous content through the Tenckhoff, after a peritoneal dialysis regimen due to acute renal failure and fluid overload.

Results: Despite the therapeutic measures taken, the patient maintains centuries-old losses of lymph, which lead to nutritional and immunological deterioration with the consequent multiple organ dysfunction and death.

Conclusions: The perpetuation of lymph losses in the postoperative period of cardiovascular surgery produces a nutritional and immunological deterioration of the patient, with a high risk of mortality due to sepsis.

Keywords

Chyloperitoneum, Peritoneal dialysis, Acute renal dysfunction

Introduction

Chylous ascites, or chyloperitoneum, is a rare form of ascites, characterized by a milky-looking fluid that contains high levels of triglycerides and exceeds those found in plasma (>200 mg/100 ml). Its incidence ranges from 1 in 20,000 to 1 in 187,000 admissions, in referral hospitals and specialized care [1].

Clinical Case

Newborn, from a dystocic delivery at 39 weeks of gestation, with a postnatal diagnosis of simple Transposition of the Great Vessels (TGV) and a weight of 3300 g.

At 15 days of age, he underwent surgery and anatomical correction was performed by Arterial Switch with extracorporeal circulation time 141 minutes, aortic clamping time 85 minutes, at 28 degrees of temperature and conventional hemofiltration (200 ml) and modified (150 ml) after cardiopulmonary bypass. He left the operating room with a Tenckhoff catheter in place, open sternum and supported with inotropics: epinephrine 0.2 Mcg/kg/min and norepinephrine 0.3 Mcg/kg/min. Antimicrobial treatment was started with Cefazolin and Gentamicin.

Physical Exam

Blood Pressure 92/50 mmHg; heart rate 189/min. Mechanical Ventilation: Pins 30 cm H2O, FiO20.8%, PEEP 8 cm H2O, respiratory rate 35/min. SaO2: 96%

Patient in critical condition, with pale skin, livedo reticularis and blood aspirations since surgery. Chest and lungs: respiratory excursions and symmetrical vesicular murmur in both lung fields with transmitted sounds. Cardiovascular: rhythmic heart sounds, III/VI systolic murmur on the left sternal border. Jugular engorgement was not evidenced; Peripheral arterial pulses present. Abdomen: Globulous, soft, depressible, hepatomegaly of 3 cm with blunt edges and air-fluid noises (RHA) missing. Subcutaneous cellular tissue: generalized crescendo edema. Nervous system: under sedation, miotic pupils.

Complementary Exams

Hemoglobin 12.5 g/dl; 10.3 x 109 L leukocytes; 48% segmented, 52% lymphocytes; platelets 160 x 109 l. Prothrombin time C-13.2 P-35.6. Glycemia 9.4 mmol/l; creatinine 81 mmol/l; total protein 43 g/l, albumin 55 g/l. Glutamic oxaloacetic serum transaminase (SGOT) 22 U/L, serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT) 109 U/L; CRP: 4.2 mg/dl; triglycerides 96 mg/dl; PVC: 20 mmHg; IAP (indirectly measured through a femoral catheter at the level of the inferior vena cava): 18 mmHg.

Arterial gases: PO2: 39.5 mmHg, PCO2: 54.3 mmHg, SaO2: 73.3%. pH 7.27, HCO3 23.2 mEq/L, EB -2.8 mEq/L, sodium 161 mEq/L, potassium 2.6 mEq/L, chlorine 108 mEq/L, ionic calcium 0.88 mg/dl. Chest X-ray: diffuse veil opacity of the left lung.

Postoperative echocardiogram: preserved biventricular function, patent outflow tracts of both ventricles, without residual pathological gradient. Wide AIC with preferential left-to-right shorting. No pericardial effusion.

As complications in the immediate postoperative period, the patient presented low cardiac output and systemic capillary extravasation, so early peritoneal dialysis was started in the first 24 hours of a continuous type with 14 daily baths.

At 72 hours, complementary tests were repeated with creatinine values of 162 mmol/l and a diuretic rhythm of 0.4 mg/kg/24, and acute kidney damage was diagnosed according to the RIFLE scale [2].

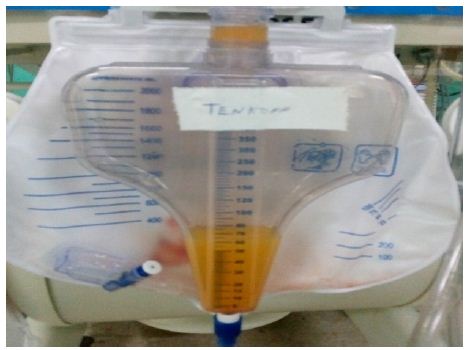

The generalized edema persists so the dialysis baths lasted for 20 days. After this time, clinical improvement was observed, the recovery of the diuretic rhythm, hemodynamic stability and decreased edema, which is why they are interrupted and leakage of a milky-looking liquid is observed through the Tenckhoff (Figure 1) and a culture attached to this tracheal secretion was positive for the growth of Enterobacter cloacae, for which antibiotic treatment with Meronem and Vancomycin was started for 10 days.

Figure 1: Peritoneal fluid.

Peritoneal Fluid Studies Reported

Cytochemical: opaline color; Slightly cloudy appearance; Pandy XX; Glucose 4.4 mmol/l; Triglycerides 433.6 mg/dl. Bacteriological: no bacterial growth, so the possibility of bacterial peritonitis is ruled out. A chyloperitoneum is diagnosed. Abdominal ultrasound: No associated tumor lesions are observed. Little free fluid in the abdominal cavity. The conduct was to keep peritoneal dialysis suspended due to the recovery of renal function with creatinine values of 91 mmol/l and a diuretic rhythm of 1.5 ml/kg/day. The Tenckhoff is maintained with losses of around 300 ml/day; The enteral route is suspended, guaranteeing parenteral nutritional support for 14 days in which the Tenckhoff debit remained at centennial figures. Albumin is added to the treatment to replace protein loss and is supported with Biomodulin T to reinforce the immune response. Severe right ventricular dysfunction; evident by hepatomegaly, wet rales in both lung fields, pleural effusion, gallop rhythm, ascites, and capillary leakage; they perpetuate the picture. Petechial lesions appear in the abdomen suggestive of fungal sepsis, continuous with high ventilatory parameters, increased edema, large losses due to Tenckhoff and manifestations of digestive bleeding, peritoneum and urinary tract. A picture of super added sepsis is presented, with a positive blood culture for yeast growth, and Amphotericin B is added to medical treatment.

Despite the strategies taken, the losses by the Tenckhoff were higher than the patient’s blood volume. The patient does not respond to antimicrobial therapy and it is decided change of antibiotic for Tazocín and Colistin without achieving favorable results. Secondary to multiple organ dysfunction, significant metabolic disturbances in the patient destroy life. The infrequent presentation of this entity in the postoperative period of Cardiovascular Surgery, associated with its difficult management, motivates the presentation of the case.

Discussion

There is an anatomical structure in the body called the thoracic duct responsible for absorbing and transporting lymph from the lymphatic vessels. When there is a disruption in lymphatic emptying, either due to loss of continuity or obstruction in these ducts at the abdominal level, it is called chylous ascites or chyloperitoneum. (1,3) It is a rare complication published in the literature and is first reported in an article published in 1961 by Morton, after performing a paracentesis in an 18-month-old male patient with disseminated tuberculosis [3].

The etiology of chyloperitoneum is well known and among the factors that determine it are congenital causes, fibrotic causes (hematologic diseases, sarcomas, and metastases), and acquired causes. Among the latter are those that cause an increase in lymph production, such as cirrhosis and heart disease, as well as those that cause a disruption or obstruction of the thoracic duct, such as trauma, abdominal surgeries, infectious (filariasis, tuberculosis) and radiotherapy [4]. There are three pathophysiological mechanisms of chylous ascites: a lymphatic alteration, fibrosis of the lymphatic system concomitant with malignant processes and of congenital origin [5-8]. Peritoneal dialysis is sometimes associated as a causative agent of the leakage of milky-looking fluid from the Tenckhoff catheter. In 2019 a study revealed a series of 22 cases, secondary to the insertion of the peritoneal catheter or peritoneal dialysis [8-10].

In this case, the authors considered that the factors that favored the appearance of chyloperitoneum were: hyperpressure of the lymphatic vessels secondary to peritoneal dialysis, associated with a systemic venous congestion caused by right ventricular dysfunction, with disruption of the lymphatic vessels and the consequent lymph outflow. The characteristics of the milky liquid on physical examination and opaline cloudy in the cytochemical examination; were determined by an increase in triglyceride values of 433.6 mg/dl, making a differential diagnosis with bacterial peritonitis.

The consequences derived from the disturbances that are produced by associated loss of immunoglobulins and proteins cause mortality to exceed 40% due to sepsis and malnutrition [11]. At the William Soler Pediatric Cardiocenter, chyloperitoneum is not frequent, so we do not have a statistical record related to mortality.

Physiological correction surgery for transposition of the great vessels (Arterial Switch or Jatene) performed in the first 20 days of life exposes the patient to multiple risks due to age, extracorporeal circulation time and aortic clamping, which are also risk factors mortality [12]. In cardiovascular surgery, the chylothorax is observed more frequently, then the chyloperitoneum and the chylopericardium more rarely [13].

With the exit of chyle, fluids, electrolytes, proteins, fats, fat-soluble vitamins and T lymphocytes are depleted, which conditions an alteration of variable severity in nutritional status and humoral and cellular immunity, which predisposes to occurrence of opportunistic infections [14]. There is a correlation between chyle loss rates and survival; determining factor in this case, since chyle losses exceeded 100 ml every day, more than a third of the patient’s blood volume, perpetuated for more than 10 days.

Dietary management and metabolic correction, as well as the use of substances that decrease lymph production are the mainstays of treatment. The medical treatment that is described in the bibliography, includes modifications in the diet (low in fat or with medium chain fatty acids or total parenteral nutrition), intravenous medication with somatostatin and/or analogues such as octreotide, proposed by Ulibarri et al. (0.1 mg/8 hrs); with a mechanism of action that decreases gastric, pancreatic, intestinal secretion, portal and splanchnic blood flow, helping to decrease lymphatic production [5,10,11,13].

Medical treatment consisted of suspending the enteral route, guaranteeing an adequate parenteral intake, which must have produced a decrease in lymphatic flow. Albumin was used to replace the losses, since hypoalbuminemia encourages the fluid to pass into the interstitial tissues with excess protein and higher colloid osmotic pressure [15]. Biomodulin T was used to optimize the immunity, since they promote the maturation, the activity of T lymphocytes and the release by these cells of IL1, IL2, IL6, IL7, GM-CSF and others. In this case we do not have the availability of this medicine.

No response was obtained with the measures used in the patient.

Losses of nutritional, immune, and metabolic factors led to multiple organ failure and death.

Conclusions

The perpetuation of lymph losses in the postoperative period of cardiovascular surgery produces a nutritional and immunological deterioration of the patient, with a high risk of mortality due to sepsis.

References

- Caravaca-García A, Rodríguez-Contreras D, Elhendi-Halaw W (2016) Ductus torácico: vecino desconocido e incómodo. Acta Otorrinolaringol Gallega 9: 98-102.

- Díaz de León-Ponce MA, Briones-Garduño JC, Carrillo-Esper R, Moreno-Santillán A, Pérez-Calatayud A (2017) Insuficiencia renal aguda (IRA) clasificación, fisiopatología, histopatología, cuadro clínico diagnóstico y tratamiento una versión lógica. Rev Mex Anestes 40: 280-287.

- Rodrigo del Valle Ruiz S, González Valverde FM, Tamayo Rodríguez ME, Medina Manuel E, Albarracín Marín-Blázquez A. Quiloperitoneo incidental asociado a hernia de Petersen en paciente operada de bypass gástrico laparoscópico. Elsevier Rev Cir Esp 97: 351-353.

- Lizaola B, Bonder A, Trivedi HD, Tapper EB, Cardenas A (2017) Review article: the diagnostic approach and current management of chylous ascites. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 46: 816-824. [crossref]

- Uribe J, Sepúlveda R, Cruz R, Illanes P, Trucco C, Le Roy C (2018) Ascitis quilosa post cirugía abdominal: caso clínico y revisión de la literatura. Gastroenterol latinoam 29: 193-199.

- Vilar-Tabanera A, García-Angarita F, Mendía-Conde E, Gómez-Ramírez J (2019) Ascitis quilosa tras colecistectomía. Presentación de un caso. Rev Cir 71: 253-256.

- Roa Colomo A, Caballero Mateos A, Vidal Vílchez B, Cervilla Sáez de Tejada E (2021) Varón de 60 años que debuta con ascitis quilosa. 44.

- Rodríguez-Sánchez MP, Hurtado-Uriarte M, Díaz-Ruiz JE, Vergara C, Cuestas JA, et al. (2019) Quiloperitoneo en diálisis peritoneal: reporte de caso y revisión de la literatura. Rev Nefrol Dial Traspl 39: 115-119.

- Moro K, Koyama Y, Kosugi Si, Ishikawa T, Ichikawa H, et al. (2016) Low fat-containing elemental formula is effective for postoperative recovery and potentially useful for preventing chyle leak during postoperative early enteral nutrition after esophagectomy. Clin Nutr 35: 1423-1428. [crossref]

- Olivar Roldán J, Fernández Martínez A, Martínez Sancho E, Díaz Gómez J, Martín Borge V, et al. (2009) Tratamiento dietético de la ascitis quilosa postquirúrgica: caso clínico y revisión de la literatura. Nutr Hosp 24: 748-750.

- Castillo F., Marín D., Linares F., Osorio A (2018) Ascitis quilosa postraumática tratada con nutrición parenteral total y octreotido, Revista Cubana de Cirugía 57: 1-7.

- Jatene Vera F, Sarria E, Ortiz A, Ruiz E (2021) Cirugía de la transposición de las grandes arterias en periodo neonatal. Cirugía Cardiovascular 28: 3-7,

- Ruz M, Guzmán M, Gómez López de Mesa C, Betancur L (2010) Quilopericardio secundario a cirugía cardiovascular. Rev Colomb Cardiol 17: 191-194.

- Valenzuela MJ, Jofré P, Reimer C, Valdés S, Grassi B (2020) Manejo nutricional de ascitis quilosa: Serie de casos y revisión de la literatura. Rev Chil Nutr 47: 1038-1042.

- Lozano González Y (2007) Linfedema. Rev Méd Electron [Seriada en línea] 29.