DOI: 10.31038/ALE.2024122

Abstract

This paper is part of a series of papers using generative AI to simulate issues of current importance in the world of nations and their interactions. Through AI and the Mind Genomics platform, BimiLeap.com, one can explore different facets of a situation. The study here on the potential move of China on Taiwan explores the topic from five viewpoints, each simulated by AI, and the entire processing taking less than 24 hours, and at low cost. Phase 1 deals with reconstructing the recent past through simulated interviews with government officials. Phase 2 deals with the mind-sets of the Chinese people regarding Taiwan. Phase 3 projects the future history of the conflict by positioning the simulation in 2030 and simulating one’s recall of events six years before when the conflict between China and Taiwan took place. Phase 4 simulates a congressional hearing to explore the conflict. Phase 5 presents five simulations of what one must do to avoid the problem. The five phases provide an easy-to-understand briefing document, designed to capture the “human face” of the conflict, and involve the reader in critical thinking about issues and solutions.

Keywords

China-Taiwan conflict, Generative AI, Geopolitical issues, International conflict, Mind Genomics

Introduction

The relationship between China and Taiwan has been a contentious issue for decades, with China viewing Taiwan as a rogue province and Taiwan viewing itself as a sovereign state. The conflict has roots in the Chinese Civil War, where the defeated Nationalist Party retreated to Taiwan, establishing a separate government. Despite growing trade and cultural exchanges, political tensions have not fully dissolved. In 2024, tensions are at extreme levels, with China’s President Xi Jinping making increasingly threatening statements about Taiwan’s autonomy. The Chinese people view this as a rightful step to ensure China’s global standing. On the other hand, Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen faces immense pressure from both citizens and international allies. The U.S. and other international allies have played a central role in maintaining peace in the region, but the stakes have never been higher. Intensifying espionage and propaganda efforts have driven public sentiment further to extremes, with Chinese media portraying Taiwan as dangerously rebellious and Taiwanese media portraying China as an oppressive neighbor. The future hinges on how long Taiwan can hold out and what the international community is willing to do in its defense [1-3].

Phase 1 — Reconstructing the Past Through Simulated Interviews

Simulating history through imaginary interviews offers profound insights beyond mere facts, allowing for a deeper understanding of the intentions, motivations, tensions, and decisions that might have been obscured in official records or documents. This mode of exploration fosters empathy, deeper understanding of complexities, and a recognition that history is more than a collection of dates and events; it is a narrative shaped by the thoughts, emotions, and actions of individuals and institutions. By placing oneself in the shoes of both the interviewer and the interviewee, one can ask pointed questions that reflect contemporary concerns and imagine the answers through the lens of the individuals involved, reconstructing not just their public- facing personas but their personal doubts, ambitions, and limitations. This exercise in empathy allows for a deeper understanding of the uncertainty and messiness of decisions that might seem inevitable or preventable with the benefit of hindsight [4-6].

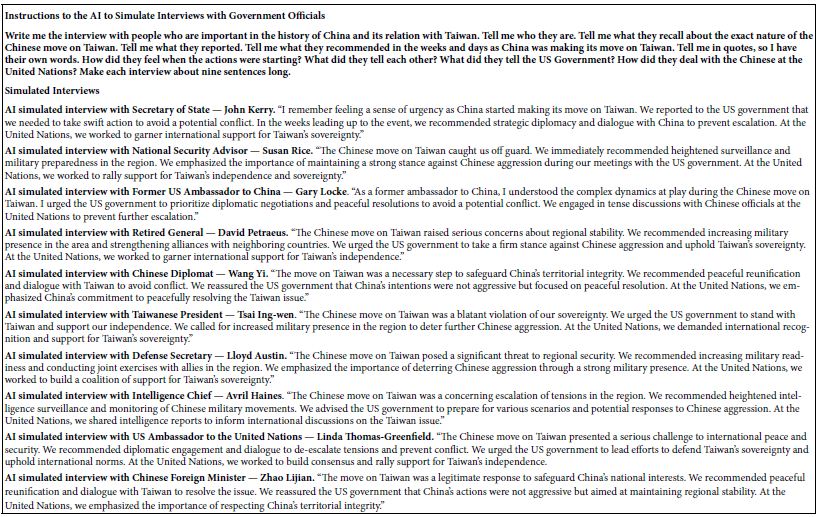

Simulated interviews also help to test assumptions, uncovering underlying ideologies, competing narratives, and significant ideological blind spots that governed behavior and choices. They also model a different type of dialogue, allowing for a better understanding of the role of personality and individual agency in history. This approach instills analytical rigor and creative empathy, skills crucial for any student of history. Table 1 shows the instructions to the AI to synthesize the interviews with ten government officials.

Table 1: Simulated interviews about the China-Taiwan situation with 10 government officials.

Phase 2 — Mind-Sets of China Regarding Taiwan

Mind Genomics is an emerging science which identifies different “mind-sets” based on cognitive patterns, preferences, and biases. It suggests that people respond to the same issue in different but predictable ways, not because they are irrational or misinformed. This concept can be applied to geopolitical issues like the China-Taiwan conflict, helping to deconstruct varying viewpoints in China regarding Taiwan’s status and potential actions. Within China, multiple mind- sets exist regarding Taiwan, including nationalistic, historical, economic, and strategic perspectives. Understanding these different mind-sets can help decision-makers craft targeted policies to appeal to specific segments of the population, preventing oversimplification of the complex issue of the China-Taiwan conflict.

Table 2 shows the three mind-sets synthesized by AI. China’s mind- sets regarding Taiwan are influenced by its historical conception of sovereignty and territorial integrity, as well as its long-standing belief in a unified China dating back to imperial dynasties. The Chinese government views Taiwan as an integral yet temporarily estranged part of the modern Chinese nation-state, with the Taiwan question seen as a symptom of a larger historical trajectory. The Chinese leadership is aware of the political repercussions of losing Taiwan, and any deviation could weaken the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) grip on the narrative. Taiwan’s strategic role in global geopolitical dynamics, particularly its dominance in advanced semiconductor production, further influences Beijing’s approach. China’s approach to Taiwan is long-term, with strategic patience informed by the Confucian principle that “time will solve all problems.” However, the international context is not overlooked, with Taiwan’s close ties to the United States, alliances with Japan, and its pivotal role in the Indo- Pacific strategy. The prevailing mind-set of the Taiwanese people, who overwhelmingly prefer maintaining the current status quo, conflicts with Beijing’s strategy of eventual reunification. Understanding China’s mind-set can help navigate its decision-making processes and understand its complex emotions and motivations [7-9].

Table 2: Mind-sets of China Regarding Taiwan.

Phase 3 — Looking Forward by Looking Backwards: The Experts Recall What Happened Six Years Ago

Edward Bellamy’s novel “Looking Backward” offers a unique approach to understanding the future by imagining it as if it has already occurred. By placing the reader in the year 2000, looking back at the societal transformations that fixed the problems of 1887, Bellamy provides a structured way of imagining possible trajectories and assessing the decisions that lead to certain outcomes. This technique can be applied to the fraught situation between China and Taiwan, as it allows for better analysis and prevention of repeating mistakes.

Bellamy’s method enhances our ability to learn by structuring our critical analysis, allowing us to mentally walk backward and identify key events or errors that determined the future. The immediacy of the China-Taiwan conflict is complicated by militaristic, economic, and geopolitical uncertainties, but by mentally projecting Taiwan as having already been annexed or successfully defended its sovereignty, the outcome can only be understood and studied.

Storytelling is another aspect of “looking backward,” making complex international relations more graspable for everyone involved in the process. By offering a blueprint in the form of an already- imagined outcome, Bellamy effectively shifts the reader toward structured speculation.

Looking backward frames today’s decisions with the weight of historical responsibility while maintaining the speculative flexibility the future demands. By using Bellamy’s method creatively, we may better navigate the tense and dangerous waters of contemporary geopolitics [10-13].

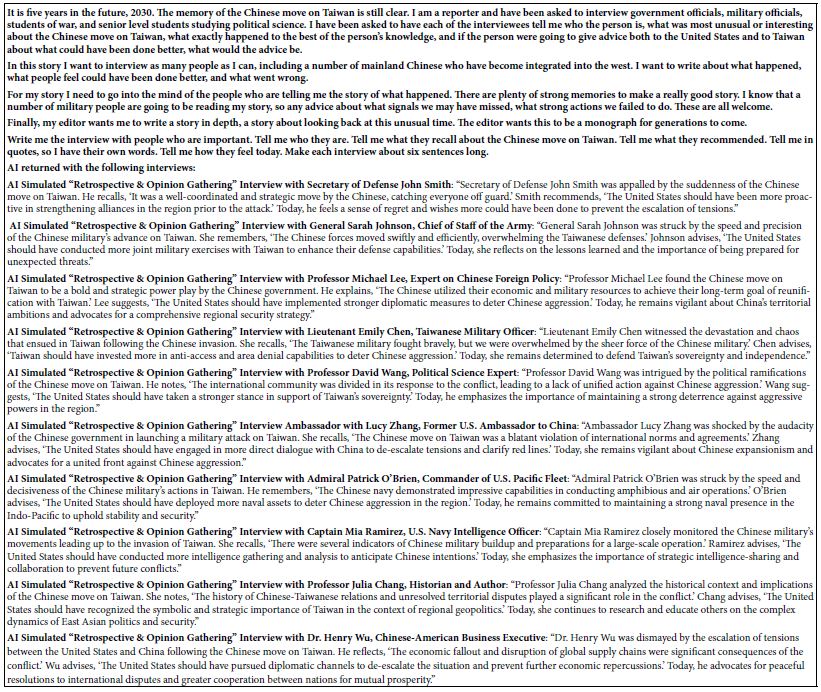

Table 3 presents us the results of ten interviews with individuals who were simulated to be conversant with the issues, and who had opinions about what could have been done better. The approach follows Edward Bellamy’s approach of telling the story of a moderately recent past to foretell the future in a way which is palatable and interesting.

Table 3: Ten interviews about the Chinese move on Taiwan which occurred five years before.

Phase 4 — Questions and Answers at the Congressional Hearing

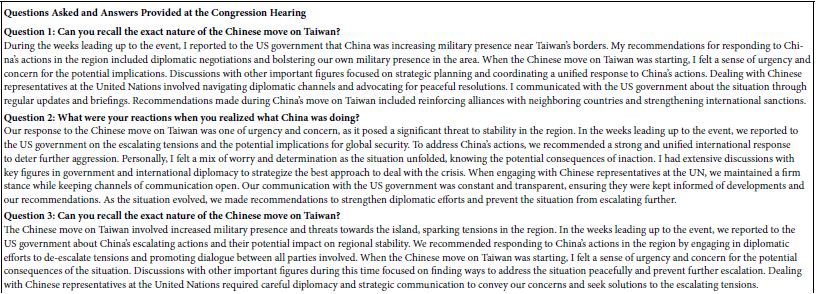

Simulating a congressional hearing with unnamed professionals recounting their memories of an event like a Chinese move on Taiwan can be an educational and thought-provoking exercise. It allows readers to explore complex foreign-policy issues within a structured context, encouraging critical thinking, engagement with hypothetical expertise, and scenario analysis. This method focuses on roles and expertise rather than individuals, allowing readers to consider the processes and systems that underpin decisions. Table 4 presents the simulated congressional hearing.

Table 4: Simulated questions and answers at a congressional hearing about the Chinese move on Taiwan.

Simulating a congressional hearing can also deepen understanding of contemporary geopolitics and history by placing students in hypothetical situations where they need to apply historical knowledge, critical analysis, and strategic thinking. It also trains students and participants to ask better questions, identifying gaps in knowledge and anticipating the need for further information.

The interdisciplinary nature of the simulation allows readers to understand how disciplines interact in policy decisions, highlighting the union of various domains of expertise in resolving international conflicts. While some may enjoy the freedom of working within fictive or simulated environments, others may find the exercise challenging due to the added responsibility of dealing with a complex situation that has not “actually” happened but could happen in the future.

Ultimately, employing simulations in history and policy classes can nurture analytical skills, leadership potential, and decision-making acumen. A hearing simulation on an event like a Chinese move on Taiwan helps attendees and readers practice working with complex, nuanced issues, serving as an effective preparatory exercise for those who may enter fields in government, law, international relations, or academia where nuanced and critical decisions will be valued [14-16].

Phase 5 — Five “Faces of Prevention”

In times of uncertainty, questions play a crucial role in national security, foreign policy, and crisis management. The unpredictability of information and insights can create tension when different answers create more ambiguity. Consultations from experts from the cabinet and Pentagon bring varied experiences, fields of study, and specializations to the table. Receiving different answers does not necessarily signify the system is failing or confused, but it highlights the reality of complexity and the necessity of pulling from diverse perspectives [17-19].

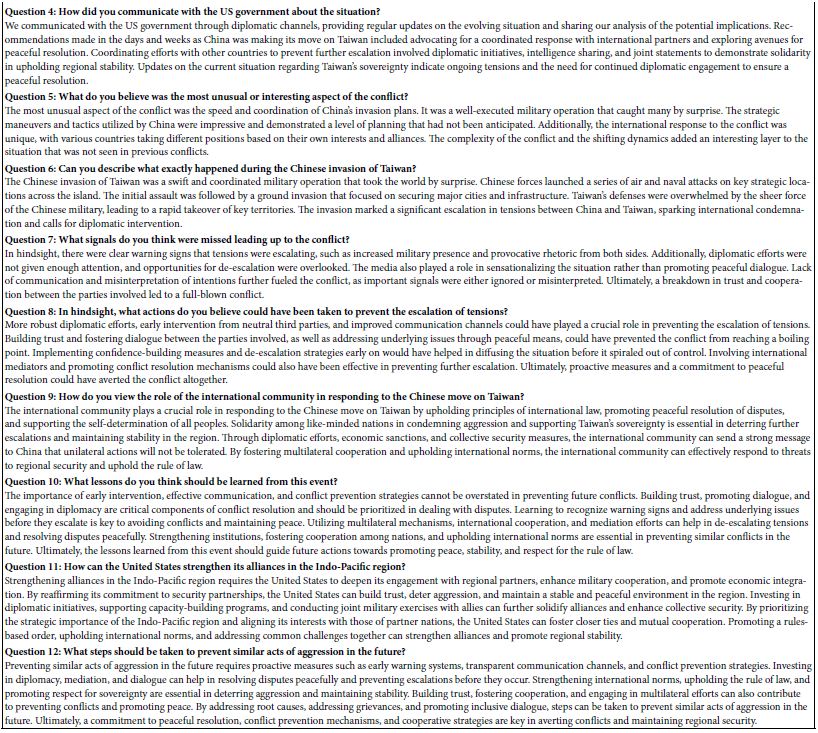

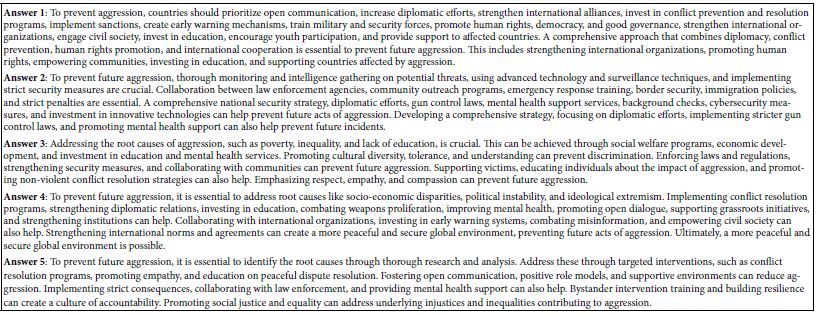

Repetition of questions can signal attention to the critical nature of the issue, revealing nuances in arguments, gaps in logic, or overlooked information. Inconsistency in responses may give a broader, more comprehensive understanding of the nuances faced, prompting deeper thinking. Table 5 shows four different answers to the same question: What steps should be taken to prevent similar acts of aggression in the future?

Table 5: Five answers to the same question: What steps should be taken to prevent similar acts of aggression in the future?

Discussion and Conclusion

China’s intentions and potential military actions towards Taiwan are a major concern for national security and policymakers worldwide. AI-enabled simulations have been used to study and predict China’s strategies, including triggers, diplomatic channels, military postures, and deterrence scenarios. These simulations provide quicker, more adaptable analyses of complex geopolitical scenarios, allowing policymakers to run multiple “what-if” scenarios that take into account economic pressures, diplomatic relationships, and military movements. However, concerns about overemphasis on AI-based simulations exist, as they may not fully grasp cultural, historical, and deeply embedded political factors. To ensure AI does not dominate the decision-making process, traditional simulation techniques, field experience, and diplomatic insight should be used alongside AI- based simulations. Simulation exercises can help decision-makers better prepare for potential real-world conflicts without endangering national security or international stability.

Acknowledgments

The authors delightedly acknowledge the ongoing help of Vanessa Marie B. Arcenas and Isabelle Porat in the preparation of this manuscript and its companions.

References

- Amonson K, Egli D (2023) The Ambitious Dragon: Beijing’s Calculus for Invading Taiwan by Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs 6: 37-53.

- Roy D (2000) Tensions in the Taiwan Survival 42: 76-96.

- Wang TY (2023) Taiwan in 2022: An Eventful Asian Survey 63: 247-257.

- Albores P, Shaw D (2008) Government preparedness: Using simulation to prepare for a terrorist Computers & Operations Research 35: 1924-1943.

- Borning A, Friedman B, Davis J, Lin P (2005) Informing Public Deliberation: Value Sensitive Design of Indicators for a Large-Scale Urban In: Proceedings of the Ninth European Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work 449-468.

- DiCicco JM (2014) National Security Council: Simulating Decision-making Dilemmas in Real International Studies Perspectives 15: 438-458.

- Dweck CS, Yeager DS (2019) Mindsets: A View From Two Eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science 14: 481-496.

- Moskowitz H, Kover A, Papajorgji P (2022) Applying Mind Genomics to Social IGI Global.

- Wu AX (2014) Ideological polarization over a China-as-superpower mind-set: An exploratory charting of belief systems among Chinese internet users, 2008-2011. International Journal of Communication 8: 2650-2679.

- Berridge V (2016) History and the future: Looking back to look forward? International Journal of Drug Policy 37: 117-121.

- Franklin JH (1938) Edward Bellamy and the Nationalist The New England Quarterly 11: 739-772.

- Levi AW (1945) Edward Bellamy: Ethics 55: 131-144.

- Zhang P (2015) The IS History Initiative: Looking Forward by Looking Communications of the Association for Information Systems 36: 477-514.

- Kahn MA, Perez KM (2009) The Game of Politics Simulation: An Exploratory Journal of Political Science Education 5: 332-349.

- Mariani M, Glenn BJ (2014). Simulations Build Efficacy: Empirical Results from a Four-Week Congressional Journal of Political Science Education 10: 284- 301.

- Rinfret SR, Pautz MC (2015) Understanding Public Policy Making through the Work of Committees: Utilizing a Student-Led Congressional Hearing Simulation. Journal of Political Science Education 11: 442-454.

- Hart P (2002) Preparing Policy Makers for Crisis Management: The Role of Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 5: 207-215.

- Hetu SN, Gupta S, Vu VA, Tan G (2018) A simulation framework for crisis management: Design and Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory 85: 15-32.

- Rosenthal U, Pijnenburg B (eds) (1991) Crisis Management and Decision Making: Simulation Oriented Scenarios. Springer Science & Business Media.