Abstract

Background: The effective implementation of evidence-based practices (EBPs) in healthcare is essential for enhancing patient outcomes. However, in acute care settings, the adoption of EBPs can be inconsistent due to organisational barriers, hierarchical structures, and limited resources. Interprofessional collaboration and continuous professional development (CPD) are critical in overcoming these challenges, empowering nurses to apply evidence-based knowledge in clinical practice.

Aim: This study aims to investigate how EBPs are implemented in two large acute care hospitals in East England, focusing on the roles of interprofessional collaboration, nurse led initiatives, and CPD in facilitating or hindering EBP adoption.

Materials and method: A collective qualitative case study design was used to examine EBP implementation across two hospitals with different organisational contexts. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews with nurses and physicians, and non-participant observation. Thematic analysis was conducted to identify key themes.

Results: The findings highlight that formal interprofessional collaboration, such as regular interdisciplinary meetings, significantly supports EBP adoption by enhancing communication and shared decision-making between nurses and physicians. However, professional silos and hierarchical barriers remain prevalent, often slowing EBP implementation and limiting nurse input. Nurses used their clinical expertise to independently advocate for and lead small-scale EBP changes, particularly in infection control and wound care, resulting in notable patient outcome improvements. CPD emerged as a powerful enabler, boosting nurses’ confidence and capacity to challenge outdated practices and advocate for evidence-based changes.

Conclusion: Formal collaboration structures and accessible CPD are essential to successful EBP implementation. Addressing hierarchical barriers and fostering interprofessional dialogue can improve the integration of evidence-based knowledge into routine care, empowering nurses as key drivers of change.

Background

Knowledge implementation stands at the forefront of healthcare advancements, essential for driving improvements in patient outcomes and elevating overall care quality [1-3]. Evidence-based practice (EBP) in nursing involves the integration of clinical expertise, patient values, and the best available evidence to inform clinical decision-making [4]. This approach not only enhances the effectiveness of patient care but also supports the professional development of nurses by grounding practice in research and evidence [1]. However, despite substantial evidence supporting EBPs and strong endorsements from health authorities like the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), there are significant barriers to EBP implementation in acute care settings, particularly in the United Kingdom [5]. These barriers often include organisational silos, hierarchical structures, and a lack of resources and time allocated for continuous professional development, which limit the capacity of nurses to fully integrate EBPs in routine practice [6,7]. Interprofessional collaboration has been shown to significantly enhance EBP implementation, as it encourages knowledge sharing and supports decision-making across disciplines [8]. Studies have demonstrated that healthcare environments promoting interdisciplinary teamwork foster more effective communication, increase the uptake of EBPs, and ultimately improve patient outcomes [9]. Yet, evidence also highlights that healthcare organisations often operate within rigid professional silos, which impede the collaborative processes essential for EBP integration [10,11]. In particular, nurses may face challenges when their input is undervalued or dismissed in favour of physician-dominated perspectives, limiting the full utilisation of their expertise and knowledge in decision-making [2]. The persistence of these silos suggests a gap in understanding the mechanisms by which interprofessional collaboration can be consistently and effectively integrated into acute care practices to support EBP.

Nurses play a pivotal role in identifying care gaps and initiating evidence-based changes due to their continuous patient interactions and hands-on care delivery experience [12]. Studies indicate that when nurses are empowered with autonomy and professional development opportunities, they can act as change agents, advocating for and implementing EBPs independently, which positively impacts patient care [13,14]. Nonetheless, despite the recognised value of nurse-led EBP initiatives, healthcare systems often lack structures that empower nurses to independently lead such efforts, particularly in resource-limited environments where formal professional development opportunities may be scarce [15]. This challenge is compounded in acute care settings where workload pressures and staffing shortages can further limit the ability of nurses to dedicate time to EBP [6]. Addressing these barriers through targeted support, professional development, and restructuring of roles could enable nurses to make greater contributions to evidence-based improvements. A key factor in empowering nurses to lead EBPs is continuous professional development (CPD), which has been shown to significantly increase confidence, advocacy skills, and the ability to challenge outdated practices [16]. However, studies highlight disparities in access to CPD, particularly in settings with limited resources [17]. While some research advocates for structured CPD to enhance EBP implementation [18], there remains a lack of comprehensive understanding regarding the ways CPD and nurse empowerment impact EBP adoption in under-resourced acute care settings. Given the crucial role of nurses in direct patient care, addressing the gap in CPD access and exploring its impact on EBP utilisation are essential for supporting sustained improvements in healthcare quality. In response to these gaps, this study aims to investigate the dynamics of interprofessional collaboration, nurse-led initiatives, and professional development as facilitators and barriers to EBP implementation in acute care settings. By examining these factors across two large hospitals in East England, this study seeks to provide insights into the specific organisational and professional elements that enable or hinder the effective integration of EBPs. The findings will contribute to a deeper understanding of how healthcare organisations can leverage interprofessional collaboration, empower nurses, and enhance CPD to optimise patient care and support sustained EBP adoption.

Material and Methods

Research Design

This study utilises a collective qualitative case study design. The collective case study approach is ideal for examining multiple cases with shared characteristics, allowing cross-case comparison and deeper analysis of complex phenomena like EBP in healthcare settings [19]. The qualitative case study design ensures a thorough and nuanced understanding of EBP implementation challenges across diverse hospital environments [3]. The study followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) [20].

Study Settings

The study took place between September 2017 and July 2023. Purposive sampling was conducted in two acute care settings in the East Midland region of England. The sample included one mid-sized general hospital (600 beds) and one large general hospital (700 beds), both selected to represent diverse leadership experiences and organisational contexts. These hospitals, the largest in the region, shared similar geographical and socio-cultural characteristics and were chosen to explore EBP in a complex clinical environment with rich data potential. The decision to focus on these two hospitals was driven by practical considerations of cost, time, and accessibility, aligning with Stake’s [21] recommendation to select cases that are both welcoming and feasible for research.

Sample Size and Participants

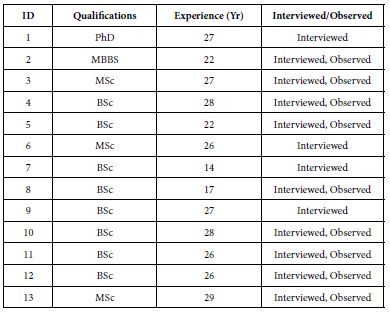

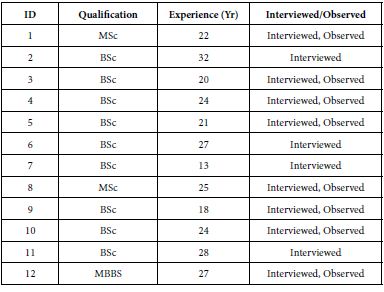

A total of 23 staff nurses (SNs) and nurse managers (NMs) and 2 Physicians participated in the study. The inclusion criteria were: (1) individuals with at least two years of experience working in these settings; and (3) those willing to participate and who signed the informed consent form. Participants were excluded if they had to withdraw due to work-related commitments or health issues during the interview period. Tables 1 and 2 present the demographics of participants. Participants in both study sites were similar. The participants’ years of experience ranged from 6 to 35 years, reflecting a broad spectrum of clinical expertise across both cases.

Table 1: Participants’ Demography (Site 1).

Table 2: Participants’ Demography (Site 2).

Data Collection

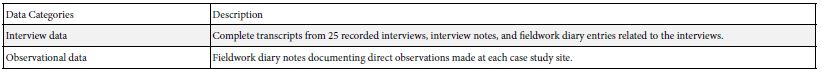

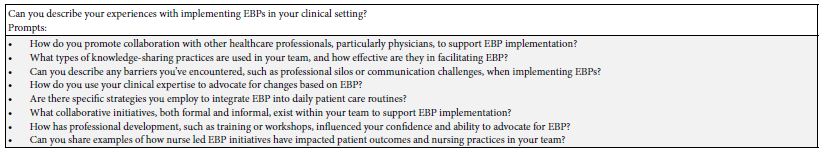

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and non-participant observation (Table 3), enabling triangulation and validation of findings [22]. Interviews were guided by an interview guide (Table 4), recorded, and transcribed. Non-participant observation captured real-life interactions, providing insights into the practical implementation of evidence-based practices. In both sites, the lines of communication for EBPs were well-established, with the Research and Development (R&D) Unit playing a key role in facilitating communication and disseminating evidence-based guidelines. The R&D and Practice Development Units were also involved in developing local evidence guidelines for their respective teams.

Table 3: Data sources

Table 4: Interview Guide

Data Analysis

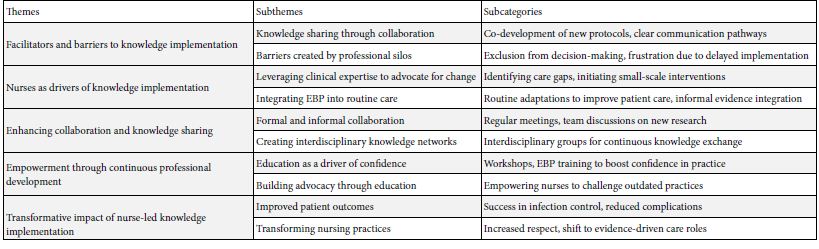

Braun and Clarke’s [23] thematic analysis framework was employed to systematically organise the finding following six key phases. The process began with familiarisation, where interview data, field notes, and observations were reviewed to understand participants’ experiences with EBP. During coding, key segments were labelled, including ‘collaborative protocol development’ ‘exclusion from decision-making’ and ‘empowerment through training’. These codes informed broader themes in the next phase: ‘Facilitators and Barriers to Knowledge Implementation’ ‘Nurses as Drivers of Knowledge Implementation’, ‘Enhancing Collaboration and Knowledge Sharing’, ‘Empowerment through Professional Development’, and ‘Transformative Impact of Nurse-Led EBP’. Themes were then reviewed for coherence and refined for clarity, defining each as it related to the study’s focus. For instance, ‘Knowledge sharing through collaboration’ addressed co-developed protocols, while ‘Barriers created by silos’ highlighted decision-making exclusions. In the final report, these themes collectively illuminated facilitators, barriers, and the impact of nurse led EBP, presenting a cohesive narrative on EBP integration in acute care settings. Overview of the key themes is presented in Table 5.

Table 5: A summary of key themes

Ethical Considerations

This study followed the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and received approval from the University of Northampton Research Ethics Committee. Each hospital’s management also granted permission for participant recruitment. Broader ethical approval was not required, as the study did not involve minors, clinical trials, or pose any risks to participants, per UK regulations. Participants received electronic and written invitations detailing the study’s purpose, confidentiality, data handling, and their right to withdraw without consequences. Informed consent was obtained in line with GDPR. The researcher shared their professional background and explained the study’s aims to build trust [22], ensuring anonymity in reporting. All data will be securely stored and destroyed after publication, and participants were treated with respect throughout.

Rigour and Reflexivity

The study adhered to principles of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability [22]. Triangulation, prolonged engagement, and multiple data collection methods, including interviews and observations, were employed to capture diverse perspectives. Spending eight months in the field enhanced credibility by providing a thorough understanding of issues affecting EBP implementation. The research process was meticulously documented, with detailed contextual information and a clear audit trail, ensuring transferability and potential replication [21]. Participant quotes supported data analysis, ensuring transparency [19]. Reflexivity was maintained through explicit acknowledgment of the study’s philosophical foundations, and a research diary preserved consistency during analysis. Finally, the COREQ guidelines were followed in reporting the qualitative results [20].

Findings

The findings reveal that effective knowledge implementation in acute care is influenced by interprofessional collaboration, nurse-led initiatives, and professional development. Key themes include the role of collaboration between nurses and physicians in facilitating knowledge sharing, though hindered at times by professional silos; nurses’ proactive leadership in driving EBPs, particularly in infection control and wound care; and the empowering effect of continuous professional development, which equips nurses to confidently advocate for and apply evidence-based changes in patient care.

Facilitators and Barriers to Knowledge Implementation

Findings from both sites show that the effective implementation of EBPs was influenced by the degree of interprofessional working between nurses and physicians. While collaboration often facilitated the integration of new practices, barriers still emerged where professional silos and communication breakdowns occurred. This theme explores how interprofessional collaboration supports or hinders the implementation of EBPs and highlights the challenges faced by nurses in these collaborative processes.

Knowledge Sharing Through Collaboration

Interprofessional collaboration was a crucial factor in facilitating knowledge implementation at both sites. The sharing of expertise between physicians and nurses allowed for the co-development of new care protocols, particularly when teams had clear communication pathways. In site 1, nurses shared: “…we worked with the doctors on a new pain management protocol, and by discussing the evidence together, we were able to agree on a more effective approach. It felt like real teamwork” (Interview, Senior Nurse, S1). Similarly, I site 2, collaboration led to quicker decision-making: “…the consultants started involving us in discussions about infection control measures…we shared our observations, and they adjusted the protocols…that kind of collaboration made a huge difference.” (Interview, Infection Control Nurse, S2). This finding demonstrates how interdisciplinary collaboration fosters a mutual understanding and respect for each profession’s expertise, enabling smoother EBP implementation.

Barriers Created by Professional Silos

Despite the benefits of collaboration, professional silos were a significant barrier at both study sites, with nurses often excluded from decision-making processes. This resulted in slower implementation of evidence-based changes and frustration among nursing staff. In site 1, nurses expressed that they “had solid evidence for a change in wound care practice, but we weren’t involved in the initial discussions…it took weeks for the doctors to acknowledge our input, which delayed everything” (Interview, Senior Nurse, S1). Similar experiences were reported in site 2 with nurses stating that they “…were pushing for months to update our catheter care protocol, but we weren’t getting feedback from the doctors…they would discuss it among themselves and leave us out, which slowed down the process.” (Interview, Nurse Manager, S2). These quotes highlight the negative impact that professional silos have on knowledge implementation, with nurses feeling marginalised and unable to influence critical decisions, despite having evidence-based insights to offer.

Nurses as Drivers of Knowledge Implementation

While hierarchical barriers remain, nurses at both study sites played a proactive role in driving the implementation of EBPs. Their clinical experience, patient proximity, and understanding of care needs positioned them as key advocates for change. This theme explores how nurses used their expertise to implement EBPs, even when formal collaboration with physicians was lacking.

Leveraging Clinical Expertise to Advocate for Change

Nurses at both sites demonstrated the capacity to introduce new practices based on evidence, using their clinical expertise to identify care gaps and push for changes. Even in environments with limited formal collaboration, nurses were able to initiate small-scale, impactful interventions. In site 1, Ward Managers seem to have utilised their expertise to advocate for EBP implementation. For example, one of the nurses expressed “…I noticed that our pressure ulcer incidence was increasing, so I introduced a new prevention strategy…the doctors were hesitant at first, but we showed results quickly, and it became standard practice” (Interview, Ward Nurse, S1)

Nurses in site 2 appeared to have done utilised similar strategies: “we started trialling a new dressing technique based on research, even before it was formally approved…once the physicians saw the improvement, they accepted it as part of our wound care protocol” (Interview, Senior Nurse, S2). These examples illustrate how nurses, using their practical knowledge, were able to implement EBPs independently, improving patient outcomes even without immediate approval from physicians.

Integrating EBP into Routine Care

Nurses at both sites consistently integrated evidence into daily care activities, often making subtle changes that did not require formal approval but had a significant impact on patient care. These routine adaptations of EBPs highlight nurses’ roles as continuous drivers of care quality improvements. In site 1, an observation of ward round revealed some clinical procedures related routine knowledge implementation: “…during rounds, a nurse adjusted a patient’s medication schedule to align with the latest evidence on pain management, even though the consultant had not yet approved the change. It made a noticeable difference in the patient’s comfort” (Observation, Ward Rounds, S1). A similar scenario played out in site 2 where during observation “nurses began closely monitoring post-surgical patients for early signs of infection, following new evidence on early detection, even though the formal guidelines hadn’t yet been updated” Observation, Post-Surgical Ward, Site 2). These examples demonstrate how nurses are able to integrate evidence into routine care processes, subtly driving improvements in patient outcomes, even when formal approval or recognition from physicians is delayed.

Enhancing Collaboration and Knowledge Sharing Through Interprofessional Initiatives

While professional silos remain a challenge, both study sites showed promising examples of initiatives aimed at fostering better collaboration between nurses and physicians. These initiatives helped to break down barriers, promote knowledge sharing, and accelerate the implementation of EBPs.

Formal and Informal Collaboration

A structured collaboration initiatives were established in site 1, with regular meetings to discuss new research and evidence-based changes in practice. This formal collaboration significantly improved communication and sped up the adoption of EBPs. One of the physicians shared: “…we’ve started having weekly meetings where the whole team, including nurses, discusses new research…it’s really improved our teamwork and made it easier to agree on new practices.” (Interview, Physician, S1). On the other hand, collaboration was less formal in site 2, but still made a positive impact as expressed by some of the nurses: “|…we don’t have regular joint meetings yet, but I’ve noticed that the doctors are increasingly asking for our input during rounds…it’s a good start” (Interview, Senior Nurse, S2). These examples suggest that while formal structures may enhance collaboration, even informal efforts can foster better communication and improve the implementation of EBPs.

Creating Interdisciplinary Knowledge Networks

Both sites showed an emerging recognition of the need for interdisciplinary knowledge networks that enable the continuous exchange of information and expertise across professional boundaries. In site 1, one of the nurses described the value of these networks as positive. “…we set up a group where nurses and doctors present the latest evidence guideline, they’ve come across…it’s helped bridge the gap between our roles and encouraged us to adopt new practices quicker.” (Interview, Senior Nurse, S1). A similar approach was developing in site 2 as indicated by the quote: “…whenever we get the chance to sit down together and discuss cases, it leads to real learning…that’s when the best ideas come up, and we’re able to implement them” (Interview, Nurse Manager, S2). The recognition of interdisciplinary knowledge sharing at both sites emphasises the importance of creating formal structures to support this collaborative learning, which is crucial for timely and effective EBP implementation.

Empowerment Through Continuous Professional Development

Education and continuous professional development are critical for empowering nurses to lead the implementation of EBPs. Both sites recognised the importance of investing in nurse education to strengthen confidence, knowledge, and the ability to advocate for evidence-based changes.

Education as a Driver of Confidence

Structured professional development opportunities, including workshops and training on EBPs, had a positive impact on nurses’ ability to implement new practices confidently. One of the nurses shared: “…after attending regular workshops on EBP, I feel much more confident bringing new ideas to the table…it’s made a huge difference in how we approach care” (Interview, Nurse Manager, S1). In site 2, education appeared to be self-driven, with nurses seeking out external opportunities: “…we don’t have as many formal training programmes, so we’ve had to find our own opportunities for development…it’s been challenging, but it’s also made us more proactive” (Interview, Senior Nurse, S2). These differing approaches highlight the need for more structured educational support at all sites to empower nurses in knowledge implementation.

Building Advocacy Through Education

Professional development not only improved knowledge but also empowered nurses to challenge outdated practices and advocate for EBPs. Nurses across both sites reported feeling more equipped to engage with physicians after receiving training. One of the nurses remarked: “…the EBP training gave me the tools I needed to confidently push for changes in the ward…now, I’m not afraid to challenge practices that don’t align with the evidence…” (Interview, Nurse, S1). Similarly, in site 2 “…the more I learn about the latest research, the more I feel I can make a real difference in care, even if it means going against established practices” (Interview, Senior Nurse, S2). These findings demonstrate how education enhances nurses’ capacity to advocate for evidence-based care and challenge traditional, less effective practices.

Transformative Impact of Nurse Led Knowledge Implementation

When nurses are empowered to implement EBPs, the results are transformative, both in terms of patient outcomes and the evolution of nursing practice. This theme explores the direct impact of nurse-led knowledge implementation on patient care and the professional development of nursing teams.

Improved Patient Outcomes

Both sites reported significant improvements in patient outcomes following the successful implementation of EBPs led by nursing teams. These improvements were particularly evident in infection control and wound care management. In site 1, a nurse shared: “…since we introduced the new infection control guidelines, we’ve seen a dramatic reduction in hospital-acquired infections…it’s been one of our biggest successes” (Interview, Infection Control Nurse, S1). In site 2, similar results were observed in post-operative care: “…the changes we made to wound care, based on the latest evidence, have reduced complications for our patients. It’s really shown how powerful EBPs can be” (Interview, Senior Nurse, S2). These success stories highlight the significant positive impact of nurse led EBP implementation on patient safety and care quality.

Transforming Nursing Practices

In addition to improving patient outcomes, nurse led EBP implementation has transformed nursing practices at both sites. Nurses reported feeling more empowered and respected within their teams, as their roles evolved from task-oriented responsibilities to research-driven care leadership. In site 1, a nurse reflects: “…implementing EBPs has changed how we work…it’s given us more credibility and made nursing more evidence-driven, which is how it should be” (Interview, Nurse Manager, S1). A similar sentiment was expressed in site 2: “…we’re no longer just following orders…we’re part of the decision-making process, and it’s changed how we see ourselves as professionals” (Interview, Senior Nurse, S2). These transformations underscore the critical role nurses play in leading the adoption of EBPs and improving the overall quality of care through evidence-driven practices.

Discussion

The findings of this study reveal complex interplays between interprofessional collaboration, hierarchical structures, and nurse-led initiatives in implementing EBPs within acute care settings. Key themes such as knowledge sharing, barriers due to professional silos, and the role of CPD emerged, all of which reinforce the necessity of a collaborative and empowering healthcare environment for EBP. These findings align with previous research while also highlighting unique challenges and opportunities within the study sites. The findings indicate that interprofessional collaboration significantly facilitates EBP adoption, a view supported by Reeves et al.., [8], who argue that interprofessional teamwork enhances knowledge exchange, ultimately leading to improved patient outcomes. Regular interdisciplinary meetings allowed nurses and physicians to share insights and align protocols, illustrating how formalised structures can improve communication, a point echoed by Grimshaw et al., [11]. However, the lack of formal collaboration structures slowed EBP adoption, suggesting that the absence of structured interactions may undermine the speed and efficacy of implementing evidence-based changes. Sullivan et al., [10] similarly argue that professional silos and the absence of regular interdisciplinary meetings can hinder EBP adoption, creating inefficiencies in decision-making. This comparative insight supports the notion that effective collaboration is contingent on formal structures that facilitate dialogue across professions, yet the findings also suggest that even informal collaboration, as observed at Site 2, can initiate positive change, albeit more slowly. Both study sites reported significant barriers due to professional silos, with nurses often excluded from decision-making processes. This aligns with the work of Dunn et al., [24-29] and Ominyi et al., [2], who found that hierarchical structures in healthcare often subordinate nursing perspectives to medical authority, limiting nurses’ capacity to advocate for EBPs effectively. The hierarchical barriers evident in this study exemplify how power dynamics in healthcare can stifle nurses’ evidence-based suggestions, even when such recommendations have the potential to improve patient outcomes. Brown et al., [15] also identified these silos as sources of frustration, as healthcare workers experienced delays in practice change implementation due to a lack of engagement and feedback from other professional groups. These barriers suggest that healthcare organisations must address hierarchical dynamics to facilitate a more inclusive decision-making process, enabling nurses to participate fully and contribute their insights into patient care practices.

Despite the hierarchical constraints, nurses at both sites demonstrated a proactive approach to EBP, using their clinical expertise to introduce evidence-based changes in infection control and wound care. This finding aligns with Harvey et al., [1], who highlight the critical role of nurses as change agents in direct patient care. Moreover, Gerrish et al., [6] found that empowering nurses to act independently often led to improved patient safety and care outcomes. Nurses in this study leveraged informal knowledge-sharing networks to drive improvements in practice, particularly when formal approval from physicians was not immediate. This self-driven initiative underscores the potential of nurse-led interventions in advancing EBP, even within restrictive organisational structures. The findings emphasise the importance of CPD in empowering nurses to implement EBPs confidently. Study findings reveal that structured CPD opportunities can boost nurses’ confidence in suggesting evidence-based changes, a result consistent with McCormack et al. [16], who argue that CPD enhances practitioners’ capacity to challenge outdated practices. However, Site 2’s reliance on self-driven educational pursuits illustrates the limitations of under-resourced environments, where formal CPD support is sparse. The disparity between the two sites reinforces Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt’s [4] argument that healthcare organisations must invest in continuous, structured professional development to support sustained EBP integration. Without organisational support for CPD, nurses may struggle to access the resources and training necessary to lead evidence-based improvements effectively. The study highlights the importance of interprofessional collaboration and nurse-led initiatives in effective EBP implementation. Formal interdisciplinary meetings enhance communication, decision-making, and reduce silos, thereby improving patient care. Additionally, investing in structured CPD for nurses builds confidence and strengthens their advocacy for evidence-based changes. Healthcare organisations should prioritise these areas to support sustained EBP integration and optimise healthcare delivery. For future research, examining ways to minimise hierarchical barriers and exploring the long-term impact of collaboration structures on EBP are essential. Research on structured CPD programmes, particularly in resource-limited settings, and identifying best practices in nurse-led EBP initiatives could further support patient care improvements.

Strengths and Limitation

This study’s strengths lie in its use of a collective qualitative case study design, providing an in-depth exploration of knowledge implementation across diverse acute care settings. Through triangulation of data from interviews, observations, and document analysis, the study ensures a comprehensive understanding of facilitators and barriers in EBP adoption. However, the study has limitations; the perspectives primarily represent staff nurses, nurse managers, and physicians, potentially overlooking insights from other key stakeholders, such as patients and policymakers, which could further enrich the understanding of interdisciplinary challenges in knowledge implementation.

Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of interprofessional collaboration, CPD, and nurse empowerment in implementing EBP within acute care settings. However, challenges persist, particularly regarding hierarchical barriers and inconsistent CPD support. Formal structures, such as interdisciplinary meetings, significantly enhance EBP adoption, though informal collaboration can still foster progress. Findings emphasise that nurses, even with limited formal support, can lead impactful EBP initiatives, illustrating their role in advancing patient outcomes. Further research should address strategies to reduce professional silos and support structured CPD, especially in resource-limited environments, to enable sustainable, nurse-led EBP integration in healthcare.

Acknowledgements

We wish would appreciate all nurses who participated in this study.

Author Contributions

JO and NA contributed to the conceptualisation and methodology of this study. JO and NA were involved in the investigation and validation of the results. JO and NA were responsible for data curation and formal analysis. JO contributed to the drafting of the manuscript, while NA reviewed and edited. JO supervised the study and provided necessary resources. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None received.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Declarations

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

This study received approval from the University of Northampton Research Ethics Committee. Each hospital’s management also granted permission for participant recruitment. Broader ethical approval was not required, as the study did not involve minors, clinical trials, or pose any risks to participants, per UK regulations. They were informed that they could refuse to answer any questions or withdraw from the study at any time. All recordings were securely stored in accordance with confidentiality principles.

Consent to Publish

Not Applicable.

Competing Interests

We declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Harvey G, Kitson A, Wilson P (2020) Accelerating the impact of evidence-based practice in healthcare. J Nurs Scholarsh 52: 65-74.

- Ominyi J, Ezeruigbo A, Udo U (2020) Challenges of implementing EBP in healthcare: perspectives from nurses. J Clin Nurs.;48: 278-285.

- Rycroft-Malone J, Burton C, Hall B, McCormack B, Smith D (2024) Evidence-based healthcare: a systematic review and recommendations. J Health Res 33: 433-449.

- Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E (2019). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: a guide to best practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health.

- Jones M, Cartwright P, Allen D, Ferguson M (2020) Strategies for EBP in UK healthcare settings. Health Serv Res 44: 1122-1129.

- Gerrish K, Cooke J, Stainton K, Dean L (2017) Evidence-based practice and patient outcomes in acute care. BMJ Open

- Dunn L, Smith R (2019) Addressing silos in EBP integration: an organisational approach. J Prof Nurs 35: 489-494.

- Reeves S, Goldman J, Zwarenstein M, Couper I (2017) Interprofessional teamwork: an evolving paradigm. Health Serv Res 52: 123-133.

- Zwarenstein M, Reeves S, Barr H, Hammick M, Koppel I (2019) Interprofessional education and practice: new directions for policy and practice. J Interprof Care 33: 105-113.

- Sullivan M, Copeland R, Moore J (2015) Breaking down silos to enhance EBP in healthcare teams. J Interprof Care 29: 123-129.

- Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE (2021) Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci

- Boström AM, Wallin L, Nordström G (2019) Patient-centred nursing: integrating EBP into clinical practice. J Clin Nurs 28: 1123-1131.

- Gifford W, Graham I, Ehrhart MG, Davies BL (2018) Advancing nursing roles in research and EBP. J Nurs Scholarsh 50: 68-75.

- Shiu ATY, Lee DT, Chau JP, Lo SM (2012) Empowering nurses for EBP leadership in patient care. Int J Nurs Stud 49: 1351-1358.

- Brown AJ, Shapiro M, Richards C (2021) The impact of limited CPD resources on nursing EBP: a multi-centre study. Int J Nurs Stud 78: 85-93.

- McCormack B, Manley K, Titchen A, Harvey G (2021) CPD and EBP integration in nursing. Nurs Manage 22: 13-21.

- Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham I, Zwarenstein M, McCauley L (2019) Translating research into policy and practice: the role of knowledge brokers. Health Res Policy Syst.;17: 60.

- Kueny A, Shever LL, Leeman J, Bostrom AM (2015) Facilitating the implementation of evidence-based practice through contextual support and nursing leadership. J Nurs Adm 45: 158-163.

- Polit DF, Beck CT (2017) Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19: 349-357.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG (1985) Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- Hancock DR, Algozzine B (2006) Doing case study research: a practical guide for beginning researchers 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Stake RE (1995) The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3: 77-101.

- Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, et al. (2021) Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess 15: 1-72.

- Dunn R, Neumann M (2019) Professional silos and EBP adoption in nursing and allied health. J Adv Nurs 75: 1842-1850.

- Reeves S, Pelone F, Hendry J, Lock N, Marshall J (2017) Interprofessional collaboration and teamwork. J Interprof Care 31: 540-552.

- Harvey G, Kitson A (2020) Implementing evidence into practice: a model for change in nursing. Evidence-Based Nurs 23: 12-15.

- Gerrish K, Cooke J (2017) Supporting nurses in implementing evidence-based practice: key enablers and challenges. J Nurs Manag 25: 1-9.