Abstract

Using generative AI, the paper investigates the nature of individuals who are likely to attack first responders (e.g., police, fire fighter, medical professionals). AI suggested five different mind-sets, and a variety of factors about these mind-sets, including what they may be thinking, and how they can be recognized. The approach of synthesizing mind-sets provides society with a way to understand negative behaviors, and to protect against them.

Introduction

In today’s society, the traditional feeling towards first responders such as emergency services, law enforcement and firefighters at the scene of an accident or crime, as well as doctors and nurses providing care in clinics, is usually one of respect and gratitude. These individuals are seen as heroes who put their own lives at risk to help others in need. People typically view first responders as dedicated professionals, essential to maintaining order and providing crucial assistance in emergency situations. Often, their work is so stressful that in some cases they end up suffering with PTSD years after their efforts [1-6].

However, violence against first responders, appears to be a growing threat. While underreported, studies suggest a concerning rise. A 2019 report by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) highlights that a staggering 69% of EMS personnel experienced some form of violence on the job within a year, with a third being physically assaulted (NFPA 2019).

During the past 30 years, however, the United States has experienced significant changes in societal attitudes and behaviors which end up in the often-unthinkable behavior of attacking first responders, whether these be public servants like police [7] or doctors and nurses in clinics [8-10]. At first glance this behavior seems irrational because the first responders are actively helping the public.

Among the key reasons:

Emotional Intensity and Stress: Emergency situations can be highly emotional and stressful for everyone involved. First responders often encounter distressed individuals, family members, or witnesses. The intensity of these situations can lead to aggression directed at responders [11].

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Issues: People under the influence of drugs or alcohol may act irrationally and become aggressive. Additionally, individuals with mental health conditions might not respond well to assistance. This problem is made worse by the fact that mental health services are underfunded and under supported, which increases the likelihood that first responders may face violent incidents [12].

Vocal And Emotionally Charged Skepticism Towards Government, Law Enforcement, And The Media: Some scholars suggest that this trend owes its growth to the increasingly. The result is a culture where challenging authority is increasingly the norm. Sometimes this erosion is expressed by a simple expression, ‘is nothing sacred anymore?’ [13-15].

Economic Disparities and Social Inequalities in the US; Economics and daily struggle cannot help but create pockets of resentment and frustration within marginalized communities. First responders, often interacting with these communities in times of crisis, end-up becoming targets for the projected frustration and anger emerging from this economically driven sense of powerlessness and injustice. This was recognized more than a half century ago [16]. Also adding to the distrust and antagonism towards first responders is the militarization of police forces and the general increase in the use of force by police officers. When the public views police as tyrannical or hostile, trust in law enforcement may suffer and communities may stop working together to keep the peace [17].

AI Predictions about the Future for First Responders

To understand this topic and to offer recommendations capable of minimizing attacks on these essential workers, we used the AI embedded in the Mind Genomics platform to help us understand the mind-sets of people who attack first responders. The approach asked the AI embedded in Mind Genomics (SCAS, Socrates as a Service) what would happen if the current attitude towards the first responders were to be unchecked. Our specific questions were what would happen in 2026, then in 2030.

SCAS returned with the following ‘prediction’: ‘People will probably still respect and admire first responders in 2026, but they may be worried about their safety due to the rising frequency of assaults on them. Many people may start to be more cautious of the dangers that come with becoming a doctor, nurse, or police officer in light of the increasing number of occurrences targeting these professions. There may be a rising chorus of voices demanding more funding and assistance to shore up the safety nets that now shield first responders. Looking further ahead to 2030, if the trend of attacks on first responders continues unabated, people’s feelings towards these essential workers may become deeply polarized. There may be a growing divide between those who continue to view first responders as heroes deserving of support and admiration, and those who have lost faith in the system and believe that drastic measures are needed to address the root causes of the problem. The traditional feeling of respect and gratitude towards these individuals may be overshadowed by a sense of resentment and anger at the injustices faced by those who dedicate their lives to helping others.

Deeper Understanding of the Problem of Attacking First Responders: Mind-sets and the Contribution of Mind Genomics

Based upon the foregoing ‘prediction’ by AI, we move to a deeper understanding of the minds of people who are described as ‘attacking first responders.’ The approach was based upon the work in Mind Genomics, an emerging branch of psychology dealing with how people respond to the world of the everyday [18,19].

How people respond to stimuli is influenced by their cognitive biases, cultural background, childhood, and life experiences. Studying these individual differences, Mind Genomics zeroes down on the minute details of daily life by classifying individuals according to their thoughts on a subject, their motivations for doing something, and even their barriers to action. Mind genomics achieves this by utilizing a combination of controlled experiments, data analysis, and cognitive psychology principles to identify distinct mind-sets and predict corresponding behaviors [20-22].

Recently, attention has shifted to using artificial intelligence to suggest mind-sets [23]. By using AI, it becomes possible to create a situation where the different mind-sets are identified, along with their possible ‘internal conversation before the attack’, as well as things that can be done immediately as well as long term to discourage these behaviors.

Mind Genomics Empowered by AI, to Explore ‘Who’ Attacks and Why

The rest of the paper is devoted to an exploration of different mind-sets, using AI to drive the creation of the mind-set. The AI is Chat GPT [24], with a series of prompts developed specifically for Mind Genomics. The prompts enable the user to find out specific information about a topic, and later apply AI to further ‘analyze’ the information originally provided by AI. The system is called Socrates as a Service, abbreviated as SCAS. It will be SCAS which allows us to interact with AI.

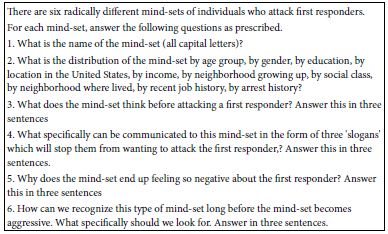

The exploration begins by presenting SCAS, viz., the embedded AI, with background material, or more correctly with a simple prompting statement. This statement, chosen by the user, is simply the statement: There are six radically different mind-sets of individuals who attack first responders. This statement is presented as fact. (Note that AI will return with only five mind-sets). The rest of the information presented to SCAS is a set of six questions, generated by the user. Table 1 shows the information and request provided to AI.

Table 1: The input information provided by the user and the request for additional information. Note that AI ended up returning only five mind-sets.

The simplicity of the system reduces the anxiety of the user. The user ends up setting the scene for AI by stating the number of mind-sets, and then requests that the AI (viz., SCAS) become a tutor, by answering six questions for each mind-set just synthesized by AI.

Once the user has specified the requested information AI returns quickly with suggestions about the mind-sets. The request has to be made properly. In the effort to create Table 2, it took four iterations to get the request correct, viz., the request shown in Table 1. The iterations are fast, requiring about 15 second each, allowing for a trial-and-error change of instructions so that they end up being clear, and without ambiguity. It is important to emphasize that the ‘errors’ instructing the AI are usually the result of ambiguous instructions, and all-too-often, instructions which contain impossible-to-satisfy requests.

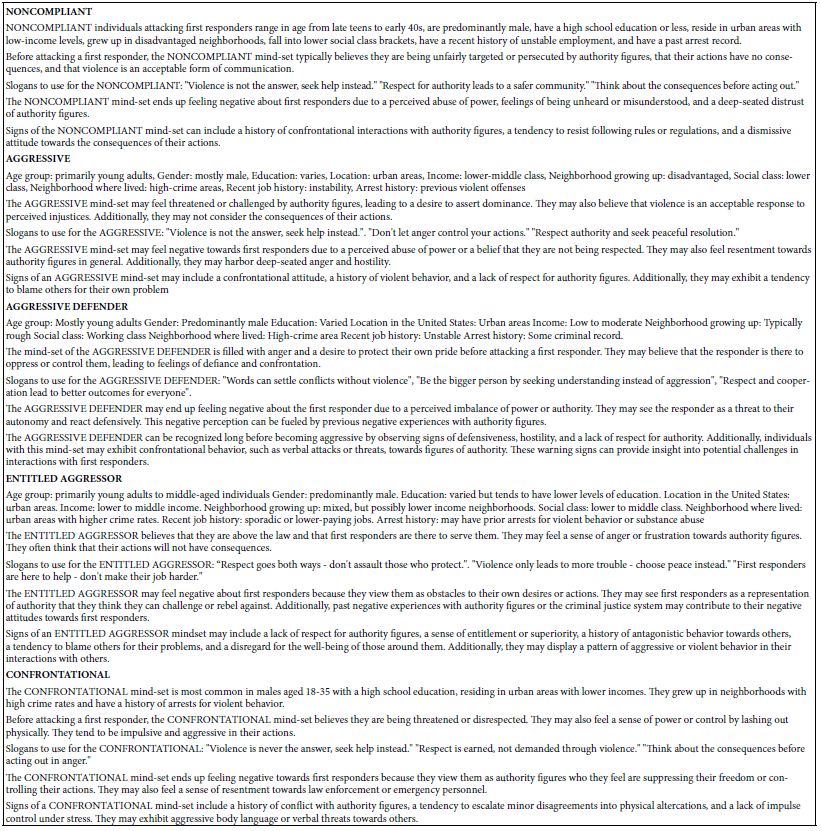

Table 2: The five mind-sets developed by SCAS as a direct response to the request

Table 2 shows the set of five mind-sets ‘synthesized’ by AI. A second iteration might return with some of the same mind-sets, but perhaps with one or two new mind-sets, as well as four of the previous five mind-sets. Note that although the user can request a certain number of mind-sets, the request ends up being a suggestion. Quite often AI returns with fewer mind-sets than requested, but never more than the number requested by the user.

The mind-sets appear with the relevant questions. Whether or not the information is accurate is not as important as the fact that within minutes the user has begun to learn about assaults against first responders. Just the information alone begins to educate, providing insights about what may be going on in the minds of those who do the assaulting, as well as what to say to them in terms of ‘slogans’.

Putting the Ideas into Action after Knowing Mind-sets

AI can predict and prevent attacks on first responders by understanding threat mindsets. By analyzing past incidents, AI can identify patterns and intervene before violence. This knowledge can de-escalate volatile encounters, suggest communication tactics, and prevent violence. With the right tools, first responders can manage unpredictable situations safely.

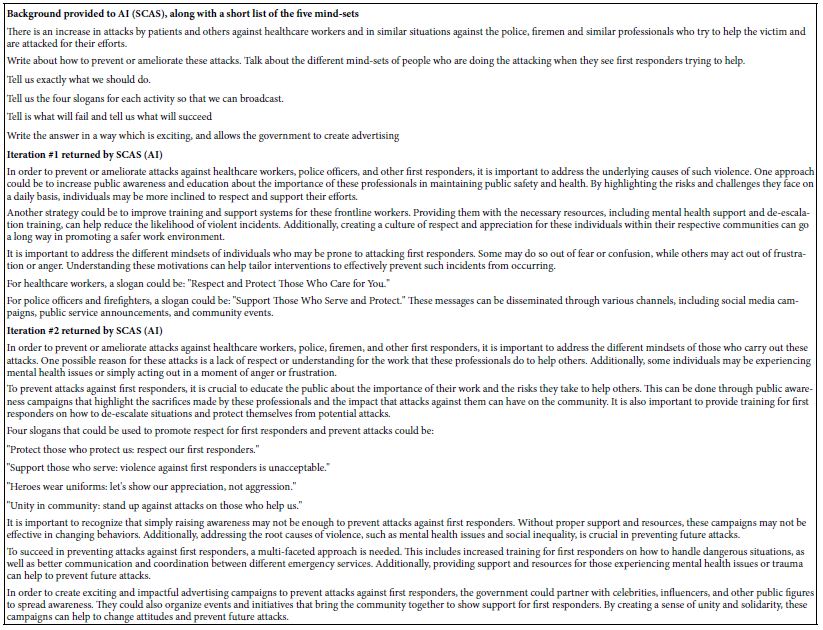

A short description of each mind-set was given to AI (SCAS), along with the background shown at the top of Table 3. The different mind-sets were provided to give AI a sense of the range of the different ways people might feel about first responders. The request, however, was to come back with a single strategy. The request was given twice, generating two iterations. These are shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Putting the ideas into action – how to prevent or ameliorate the attacks

Strategies Suggested by AI to Minimize Attacks on First Responders

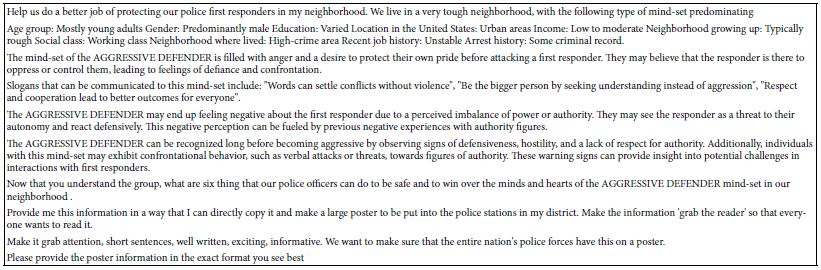

The final activity in this exploration of attacks against first responders comprises the education of professionals. Here let us assume that we are dealing with police officers in a local precinct. The assumption here is that many of the potential attackers are thought to fall into the grouping of ‘Aggressive Defender.’

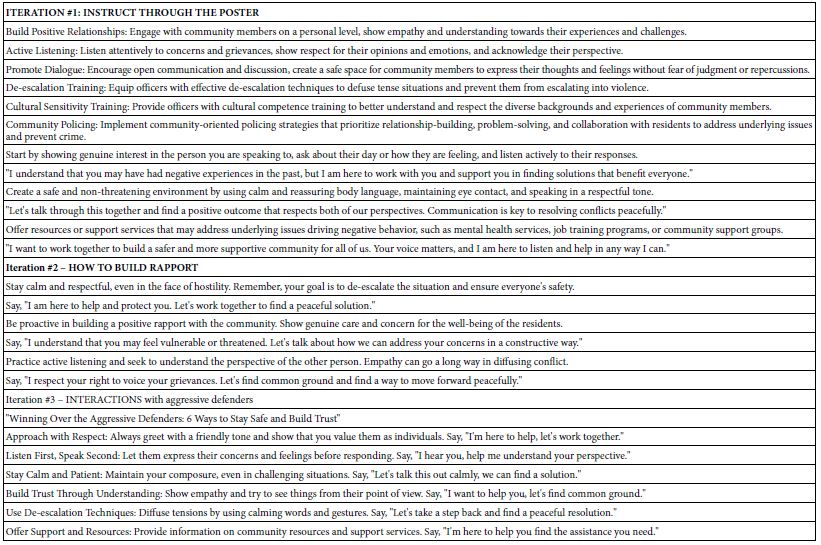

The strategy is first to create a briefing document for all officers to read (Table 4, and then to create a set of posters showing how the officers should behave towards the Aggressive Defender (Table 5). The briefing document and posters for police officers can enhance their understanding of Aggressive Defender mindsets. The briefing document provides detailed information on their characteristics, behaviors, and motivations, enabling them to anticipate, respond to, and de-escalate situations, thereby improving their safety and effectiveness on the job. In turn, the posters for the precinct teach the police officers how to effectively interact with Aggressive Defenders and potential threats.

It’s important to note that briefing documents and posters are just one method for communicating the information outlined. Multimedia formats for the same information, such as video generated by prompts or text are generally available, and could be used as an adjunct to or substitute for the poster approach outlined below.

Table 4: The briefing document for police officers, focusing on the AGGRESSIVE DEFENDER mind-set

Table 5: Three types of posters for the police precinct, dealing: The briefing document for police officers, focusing on the AGGRESSIVE DEFENDER mind-set.

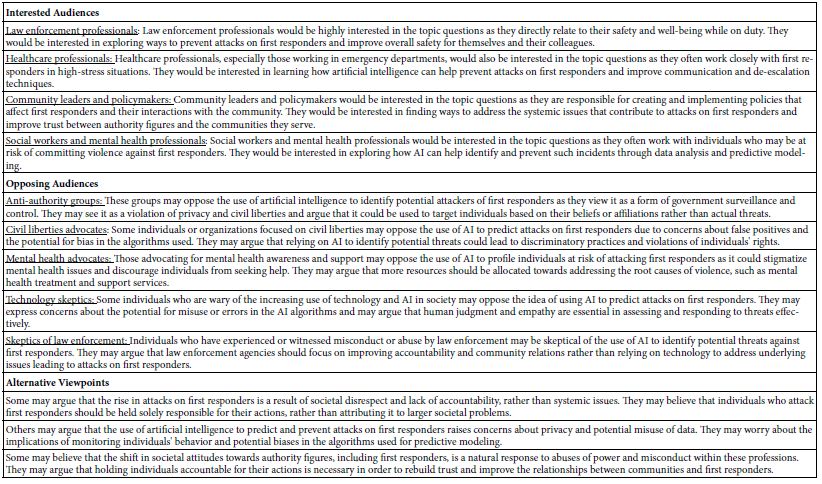

Who Would be Interested in These AI-based Simulations of Potential Attacker Mind-sets’?

We close the ‘results section’ (viz., the simulations) with a second-level analysis by SCAS. Once the iterations are complete and delivered to the user, the embedded AI reviews the information, and provides deeper analysis of what was presented in the results immediately delivered to the user. This secondary ‘summarization’ of the information occurs some time later, after the project is closed.

Part of the summarization analysis considers WHO would be the audiences. SCAS is pre-programmed to provide three different groups: those who are interested, those who are opposed, and those who think differently and may bring new viewpoints to the problem. These appear in Table 6.

Table 6: AI summarization of three different types of audiences faced with information and simulation of potential attacker mind-sets.

Discussion and Conclusions

Understanding the roots of violence today is critical to safeguarding our first responders. They are continuously exposed to risky circumstances that might develop into violent assaults. The police are often the most visible targets of this assault, but physicians at clinics are also at danger. Individual physicians have been targeted in violent assaults because they are blamed for poor medical results.

Using AI to model mindsets may assist first responders in better understanding and anticipating possible violence. Mind Genomics is a helpful tool for better analyzing and communicating with diverse mindsets. Understanding the mindsets of prospective attackers allows first responders to effectively de-escalate situations and protect themselves and others. This may greatly enhance the safety and efficacy of our first responders in high-risk circumstances.

Imagine a future in which all first responders are educated to comprehend and communicate with diverse mindsets utilizing AI technology. This might transform how our essential front-line workers handle perilous circumstances, shield themselves from injury, and maintain public support. The capacity to detect and avoid violence may be the difference between life and death for the first individuals on the scene.

References

- Alexander DA, Klein S (2009) First responders after disasters: a review of stress reactions, at-risk, vulnerability, and resilience factors. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 24: 87-94. [crossref]

- Henry VE (2015) Crisis intervention and first responders to events involving terrorism and weapons of mass destruction. Crisis Intervention Handbook: Assessment, Treatment, and Research, pp.214-47.

- Holgersson A (2016) Review of on-scene management of mass-casualty attacks. Journal of Human Security 12: 91-111.

- Jannussis D, Mpompetsi G, Vassileios K (2021) The Role of the first responder. in emergency medicine, trauma and disaster management: In: From Prehospital to Hospital Care and Beyond (pp. 11-18). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Prioux C, Marillier M, Vuillermoz C, Vandentorren S, Rabet G, et al. (2023) PTSD and Partial PTSD among first responders one and five Years after the Paris terror attacks in November 2015. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20,: 4160. [crossref]

- Wilson LC (2015) A systematic review of probable posttraumatic stress disorder in first responders following man-made mass violence. Psychiatry Research 229: 21-26. [crossref]

- Soltes V, Kubas J, Velas A, Michalík D (2021) Occupational safety of municipal police officers: Assessing the vulnerability and riskiness of police officers’ work. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 5605. [crossref]

- Huffman MC, Amman MA (2023) Violence in a place of healing: Weapons-based attacks in health care facilities. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management 10: 151-187.

- Gibbs JC (2020) Terrorist attacks targeting police, 1998–2010: Exploring heavily hit countries. International Criminal Justice Review 30: 261-278.

- Rohde D (1998) Sniper Attacks on Doctors Create Climate of Fear in Canada. New York Times.

- Richter G (2019) Assaults to EMS First Responders are Felonies in Pennsylvania, So Why Do Many Victims Feel They Do Not Receive Justice? Am J Ind Med [crossref]

- Coleman TG, Cotton DH (2010) Reducing risk and improving outcomes of police interactions with people with mental illness. Journal of Police Crisis Negotiations 10: 39-57.

- Cole J, Walters M, Lynch M (2011) Part of the solution, not the problem: the crowd’s role in emergency response. Contemporary Social Science 6: 361-375.

- Gibbs JC (2013) Targeting blue: Why we should study terrorist attacks on police. In: Examining Political Violence, Routledge (pp. 341-358).

- Gibbs JC (2018) Terrorist attacks targeting the police: the connection to foreign military presence. Police Practice and Research 19: 222-240.

- Ransford HE (1968) Isolation, powerlessness, and violence: A study of attitudes and participation in the Watts riot. American Journal of sociology 73: 581-591. [crossref]

- Smith DC (2018) The Blue Perspective: Police Perception of Police-Community Relations. University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006). Founding a new science: Mind Genomics.” Journal of Sensory Studies 21: 266-307.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A (2007) Selling Blue Elephants: How to Make Great Products that People Want Before They Even Know They Want Them. Pearson Education.

- Ilollari O, Papajorgji P, Gere A, Zemel R, Moskowitz H (2019) Using Mind Genomics to understand the specifics of a customer’s mind.The European Proceedings of Social, Behavioural Sciences EpSBS ISSN: 2357-1330.

- Moskowitz H, Wren J, Papajorgji P (2020) Mind Genomics and the Law (1st Edition). LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

- Ilollari O, Papajorgji P, Civici A (2020) Understanding client’s feelings about mobile banking in Albania. Interdisciplinary International Conference On Management, Tourism And Development Of Territory 147-154.

- Moskowitz HR, Rappaport S, Saharan S,DiLorenzo, A (2024) What makes ‘good food’: Using AI to coach people to ask good questions. Food Science, Nutrition Research 7: 1-9. [crossref]

- Aher GV, Arriaga RI, Kalai AT (2023) Using large language models to simulate multiple humans and replicate human subject studies. Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning 202: 337-371.