Abstract

Background: Female Genital Cutting (FGC) is dangerous and humiliating traditional practice that violates the right of girls and women and it is serous public health problems as it affects the health of poor Ethiopian girls and woman. Moreover, it is proved that all forms of FGC entail an immediate and long-term life treating damage to the physical, mental and social well-being of girls and women.

Objective: The objective of the study was to assess knowledge, attitude & practice towards FGC among women of reproductive age group in Jigjiga town.

Methodology: A community-based cross-sectional study design was used from January to March 2016. Structure questionnaires were used to collect data from-311study participants. Descriptive statistics was used to calculate frequency/percentage, mean and medium & the results were presented using tables, graphs and charts.

Results: A total of 311 women were included in the study. One hundred and thirty (43%) of the respondents were within the age of 15-30years. Majority 264 (84.9%)] were from Somali ethnic group and 272 (87.5%) were Muslims. 140(45%) were house wife and about 201 (64.6%) were found to be illiterate. All of the respondents have heard about FGC and 32.5% of them got information regarding FGC from Media. A total of 226 study participants practiced one or more type of the different forms of FGM/C on their daughters making the prevalence of FGC 72.7%. Of these, 158 (70.1%) were circumcised during the age < 8years. Most of the respondents 280(90.1%) knew that FGC has negative health effect. Common reasons for the practice of FGC they mentioned was to preserve virginity (49.8%) Most of those respondents (75.7%) reported that FGM/C was performed at their own home. The decision to have FGM/C was made by respondents’ mothers (42.5%), followed by father (25%]).

Conclusion: There is high practice of FGC among the community (72.7% prevalence) though they know the health impact of the FGC. As majority agrees to stop the practice efforts towards FGC prevision should focus on supporting the community on the factors that favour the practice. In addition, interventions focusing on behavioral change towards harmful traditional practices including FGC should be strengthened.

Keywords

KAP, FGC, Jigjiga, Somali region, Ethiopia

Introduction

Female Genital Cutting (FGC), sometimes called female circumcision or female genital mutilation, means piercing, cutting removing, or sewing closed all part of a girl’s or women’s external genitals for no medical reason. The operation, which lasts around 15-20 minutes, is carried out by traditional birth attendants and other untrained personnel living in the community with unsterile settings. According to its severity WHO/UNICEF/UNFPA, jointly adopted in April 1997 four type of FGC. Among the four types, Type II is commonest while the most extreme type is III [1].

There have been no comprehensive global surreys of prevalence of FGC. However, WHO estimated that 140 million of girls and women have under gone the operation and three million girls are at risk each year in 28 African countries including Ethiopia with estimated prevalence of 90% [2].

In Ethiopian FGC is practiced by Muslims and Christians as well with 90% prevalence. Study undertaken by National Committee on Traditional Practice in Ethiopia (NCTPE) about national base line survey to determine the prevalence of this practice 1997/1998 revealed regional statistics of prevalence; Afar 94.5%, Addis Ababa 70.2%, Somali 69.7%, Benishangul 52.9%, Tigray 48% and Southern region 46.3%. Other two studies conducted at Serbo and Seko Woredas, Jimma zone, Western Ethiopia revealed a prevalence of 96% & 78% respectively [3,4]. Similar study conducted on FGC in Somali on 1998 by Mohamed Omer, reported elimination of this practice would result in more than 40% and 50% reduction of Neonatal mortality and female child mortality, respectively [5].

Study done by Egyptian Care Society, showed that 39% of study women perpetuate FGC due to custom. Eighty percent believed that practice should continue. 15%-20% refused to give opinion on FGC. Sixty percent believed FGC was religious practice [6].

A study done by United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) indicated that reproduction and sexual health are affected over the entire life course of FGC- despite the seriousness of the issues, there are major gaps in knowledge about extent of the problem and the nature of successful intervention. On a report of qualitative research on KAP related to FGC in Serra Leone, all 300 interviewees (adult and young men) were strongly; opposed to FGC because of it is determinant impact on Female (women’s) health and the drain of family financial resources [1]. Another study done in Sudan mentioned that 45 people of women interviewed believed that FGC is a good practice because of it is promote cleanliness, and keep virginity [7].

According to study in entitled female genital mutilation a new challenge for health service; most Children or women are circumcised by local women and traditional midwives. Often the practice is part of cultural rituals that make the transition to womanhood and preparation for marriage. There are four forms of FGM, most of community in Somali region practice at least one of it [8-10].

All types of female genital mutilation involve removal or damage to the normal functioning of the external female genitalia and can give rise to a range of well documented physical complications. They are irreversible and their effects last a lifetime. Studies on health effects of FGC shown this practice has negative consequences for delivery, first sexual intercourse, and during menstruation. Studies on the psychological effects of FGC are scarce and need to be given due emphasis, given that FGC is one of the reported risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in women [11-16].

It is important to bear in mind that FGC is a serious public health problem, as it affects the health of poor girls and women, particularly places where the most aggressive type (infibulations) is highly practiced. Despite recognition of this sensitive issue and realization of its extent that it should be addressed, if the health, social and economic development of girls are to be met for there is still major gap in knowledge about the extent and nature of the problem and the kinds of intervention that can be successful in eliminating reducing the FGC practice.

It is thus important to assess knowledge, attitude and practice of FGC to ensure existing health priorities of the women’s reproductive age group, in order to tackle the problems with community (teachers, student/Family) participation and other partnership or stakeholders.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess the knowledge, attitude, and practice towards FGC among women of reproductive age group in Jigjiga town Somali regional state, Eastern Ethiopia in 2016.

Methods and Materials

Study Area and Study Period

The study was conducted in Jigjiga town, Capital of Somali region from January to May 2016. Jigjiga is located in Eastern part of Ethiopia 635km from the capital city, Addis Ababa. The town’s climate is sub tropic climate and receives 300-500mm annual rain fall a year, the mean annual temperature of the town is 24-26 degree Celsius (Figures 1 and 2).

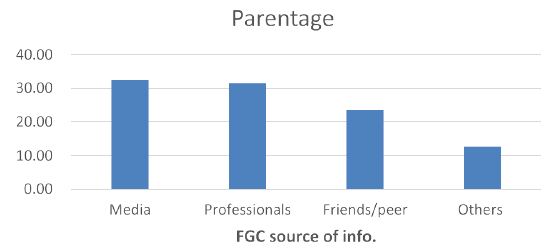

Figure 1: Source of information on Knowledge on Female Genital Cutting (FGC) of the respondents in Jigjiga town, Somali regional state, Ethiopia, April 2016.

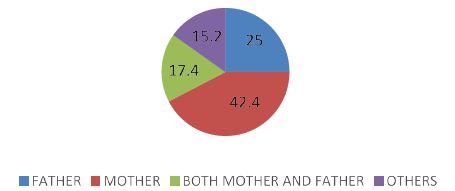

Figure 2: Decision maker for Practice towards FGC of the respondents in Jigjiga town, Somali regional state, Ethiopia, April 2016.

Study Design

A community based cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the knowledge, attitude and practice to Female Genital Cutting (FGC) of females of reproductive age group in Jigjiga town of Somali regional state, Eastern Ethiopia.

Source Population

The source populations of the study were all women of reproductive age group of Jigjiga town, Somali regional state, Eastern Ethiopia.

Study Population

The study population was randomly selected women of reproductive age group in the selected kebeles who fulfilled inclusion criteria.

Sample Size

Sample size determination was done using the sample size formula using single population proportion formula with P=proportion of women’s reproductive age group, 74% (0.74) in 2005 EDHS and adding 5% (15) to it the final sample size was 311.

Data Collection Procedure

Face to face interview method was applied by using structured questionnaires to collect the data on knowledge, attitude and practice and other socioeconomic and demographic variables from the women of reproductive age group.

Data Quality Control and Analysis

Pre-test was done on to 5% women of reproductive age who did not participate in actual study. All collected questionnaires were checked for completeness and correctness on daily basis. The data was analyzed using descriptive statistics using mean, frequency/percentages and was presented by tables, graphs and charts,

Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from Jigjiga University College of medicine and Health Science College and letter of permission was obtained from Jigjiga counsel to undergo the study. In addition participants were informed about the voluntary nature of participation and that they can exit the interview any time they decided. All data of the respondents were kept confidential.

Result

Three hundred eleven (311) women in the reproductive age group of Jigjiga town were interviewed. Majority of the respondents were Somalis (84.9%) & Muslims (90.67%) in religion. Nearly half (45%) of the study participants were house wives. Regarding their educational status, most of them were not able to read and write (67.85%). More than half of the respondents (62.4%) were single (Tables 1-4).

Table 1: Socio demographic and economic characteristics of the respondents in Jigjiga town, Somali regional state, Ethiopia, April, 2016 (N=311).

|

Feature |

Variables | Number |

% |

| Age of women in years |

15-29 |

154 | 49.5% |

|

30-49 |

157 |

50.5% |

|

|

Total |

311 |

100% |

|

| Ethnicity |

Somali |

264 | 84.9% |

|

Oromo |

18 | 5.8% | |

|

Amhara |

14 |

4.5% |

|

|

Others |

15 |

4.8% |

|

|

Total |

311 |

100% |

|

| Religion |

Muslim |

282 | 90.67 |

|

Orthodox |

11 |

3.5% |

|

|

Catholic |

7 | 2.3% | |

|

Others |

11 |

3.5 % |

|

|

Total |

311 |

100% |

|

| Occupational status |

Government worker |

70 | 22.5% |

|

Private worker |

85 |

27.6% |

|

|

House wife |

140 | 45% | |

|

Others |

16 |

5.14% |

|

|

Total |

311 |

100% |

|

| Educational Status |

Not able to read and write |

211 | 67.85% |

|

Elementary school (1-8) |

50 |

16.1% |

|

|

High school (9-12) |

36 | 11.6% | |

|

College & above |

14 |

4.5 % |

|

|

Total |

311 |

100% |

|

| Marital Status |

Single |

194 | 62.4% |

|

Married |

70 |

22.5% |

|

|

Divorced |

39 | 12.5% | |

|

Separated |

8 |

2.6% |

|

| Total |

311 |

100% |

Table 2: knowledge about the health effects of FGC on health & Common reasons why the community practice FGM Jigjiga city, Ethiopian Somali in April 2016.

|

Effects of FGC |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Ill-effect |

179 |

57.56% |

| Bleeding during delivery |

39 |

12.54% |

| Urinary infections |

54 |

17.4% |

| No effect |

31 |

9.97% |

| Others |

8 |

2.57% |

| Total |

311 |

100% |

| Reason for FGC practice | ||

| Religious approval |

47 |

15.1% |

| Preserve virginity |

155 |

49.8% |

| Avoid sexual problems |

70 |

22.5% |

| To keep hygiene and aesthetics |

23 |

7.4% |

| Others |

16 |

5.14% |

| Total |

311 |

100% |

Table 3: Distribution of woman’s attitude towards the practice of FGC Jigjiga city, Ethiopian Somali in April 2016.

|

Response towards FGC |

Variables | Frequency % | Remark | |

| NO |

% |

|||

| FGC should be stopped | Strongly agree |

162 |

52.1% |

|

| Agree |

78 |

25..1% |

||

| Neutral |

16 |

5.14% |

||

| Disagree |

39 |

12.5% |

||

| Strongly disagree |

16 |

5.14 |

||

| Total |

311 |

100% |

||

| Female should actively participate in FGC eradication | Strongly agree |

147 |

47% |

|

| Agree |

78 |

25% |

||

| Neutral |

78 |

25% |

||

| Disagree |

8 |

3% |

||

| Strongly disagree |

0 |

0% |

||

| Total |

311 |

100% |

||

Table 4: FGC practice in Jigjig city, Somali region, Ethiopia, April 2016.

|

S/N |

performed FGC practice | Number |

Percent (%) |

| 1 | Yes |

226 |

72.7% |

| 2 | No |

85 |

27.3% |

| Total |

311 |

100% |

|

| Age at which circumcised | |||

| 1-8 |

158 |

70.1% |

|

| 8-16 |

56 |

24.76% |

|

| >16 |

12 |

5.14% |

|

| Total |

226 |

100% |

|

| Place of FGC occurrence | |||

| Home |

171 |

75.7% |

|

| Do not know |

29 |

12.8% |

|

| Others (TBA, traditional healer etc home) |

26 |

11.5% |

|

| Total |

226 |

100% |

|

Knowledge on Female Genital Cutting (FGC)

All of the respondents have heard about FGC and 32.5% of them got information regarding FGC from Media followed by professionals (31.5%).

Most of the respondents 280(90.1%) knew that FGC has negative health effect. As to why FGC conducted in the community, Common reasons for the practice of FGC (nearly half of the respondents (49.8%)) mentioned to preserve virginity. In addition they reported religious approval (15.1%) as the next reason of the practice.

Attitude towards Female Genital Cutting (FGC)

Majority of the respondents 240(77.2%) agree that FGC should be stopped More than half 201(64.9%) of the respondents also believe FGC results poor sexual pleasure. In addition, majority 225(72%) of the respondents agree that female should actively participate on FGC eradication.

Practice towards FGC

A total of 226 study participants reported that one or more type of the different forms of FGM/C practice making the prevalence of FGC 72.7%. Of these, 158 (70.1%) were circumcised during the age < 8years. Most of those respondents (75.7%) reported that FGM/C was performed at their own home. The decision to have FGM/C was made by respondents’ mothers (42.5%), followed by father (25%]).

Discussion

Female genital cutting/mutilation (FGC/M) is a procedure that involves physically altering a woman’s/girl’s genitals for no health benefits. This is a practice that is deeply rooted in culture, religion, and social tradition primarily in some African and Middle East countries. It is performed by a midwife, barber, traditional healer with no surgical training, or a physician. The practice of FGC/M has been gaining increased attention as women from those countries have been migrating to the United States and Western Europe [9]. This community based cross-sectional study has attempted to assess the knowledge, attitude & practice towards FGC among women of reproductive age in Jigjiga town.

In this study, all of the respondents have heard about FGC and 32.5% of them got information regarding FGC from Media followed by professionals (31.5%). Most of the respondents 280 (90.1%) knew that FGC has negative health effect. a study done in Somalia revealed that, about 66.9% of women had good knowledge on the effects of FGC. In that Somalia study, respondents mentioned, infection 60%, bleeding 20%, and 68% difficult of labor to be the main ill effect of FGC [10-15]. This is consistency with our study finding, in contrast to our current findings, a study done in northwest Ethiopia shows that only 46.2% of women had good knowledge about the ill health effect of FGC and 53.8% of the mothers had poor knowledge about the ill health effect of FGC. This discrepancy might be due difference in study setting (facility Vs community) [9].

As to why FGC conducted in the community, Common reasons for the practice of FGC (nearly half of the respondents (49.8%)) mentioned to preserve virginity our study. In addition, they reported religious approval (15.1%) as the next reason of the practice similarly; more than half of Egyptian women believed that FGM would prevent adultery and that it is proof of a girl’s virginity and perceived that it improves marriage prospects for unmarried girls in Nigeria. This shows that traditional and religious reasons for practicing FGM are also widely accepted by females in the societies in different regions [10].

In this study, majority of the respondents 240 (77.2%) agree that FGC should be stopped More than half 201 (64.9%) of the respondents also believe FGC results poor sexual pleasure. In addition, majority 225 (72%) of the respondents agree that female should actively participate on FGC eradication. Similarly, in study conducted at Harari & Somali regions, the finding of the study reveals that 86% of study participants condemn the practice of FGC [12]. But in Similar study conducted in eastern Ethiopia showed, 47.9% of women have positive attitude, while 52.1% of women have favorable attitude against FGC practice [10]. This discrepancy might be due to combination efforts from different stake holders against FGC in the region & community awareness difference.

A total of 226 study participants reported that one or more type of the different forms of FGM/C practiced in their area making the prevalence of FGC 72.7%. As they reported 158 (70.1%) were circumcised during the age < 8years. Most of those respondents (75.7%) reported that FGM/C was performed at their own home. The decision to have FGM/C was made by respondents’ mothers (42.5%), followed by father (25%]). In Study conducted at Hadiya zone of southern Ethiopia, about 60% of the circumcisions were performed by traditional circumcisers while health professionals had performed 30% of them [14]. Similar study in Jigjiga on 2014 depicted that the prevalence of FGC among the respondents was found to be 82.6%. The dominant form of FGC in this study was type I FGC, 265 (49.3%). Four hundred and seven (62.7%) study participants had positive attitude toward FGC discontinuation. Religion, residence, respondents’ educational level, maternal education, attitude, and belief in religious requirement were the most significant predictors of FGC. The possible reasons for FGC practice were to keep virginity, improve social acceptance, have better marriage prospects, religious approval, and have hygiene [15].

On the other hand, in some countries, medical personnel, including doctors, nurses, and certified midwives perform FGM under anesthesia in health care facilities, even though it is forbidden and subject to prosecution in the west. The highest rate of use of medical personnel to perform FGM can be found in Egypt (61%), Kenya (34%), and Sudan (36%), with rates of 9% and 13%, respectively. These findings were inconsistency with our present study findings [12,16].

Limitation

Bias related to social desirability; since the study is self-reporting there is more likelihood of the participants to give culturally acceptable answer. There may be also information or recall bias as mothers were asked to recall events occurred long time.

Conclusion & Recommendation

There is high practice of FGC among the community (72.7% prevalence) though they know the health impact of the FGC. As majority agrees to stop the practice efforts towards FGC prevision should focus on supporting the community on the factors that favor the practice. In addition, interventions focusing on behavioral change towards harmful traditional practices including FGC should be strengthened.

Acknowledgment

I would like to pass my gratitude for Jigjiga town community specially the study groups who keenly supported by accepting the consent for the data collection. I would also like to pass my thanks to data collectors for their continuous effort during the data collection.

References

- World Health Organization (1997) “Female genital mutilation: a joint WHO/UNICEF/UNFPA statement,” WHO, Geneva.

- WHO (1998) “Female genital mutilation overview,” Geneva, Switzerland press.

- National committee on traditional practices in Ethiopia (NCTPE) (1997) “FGM,” Ethiopia, Addis Abeba.

- Abate A, Kifle M (2002) “Prevalence of female genital mutilation and attitude of mothers towards it” 12.

- Mahamed OA (1999) “Female circumcision and child mortality in urban Somali region”.

- “Egyptian Fertility care society, population council, Asia and East operation research and technical assistance final report,” Egypt, Cairo, November, 1996.

- Herieka E, Dhar J (2003) “Female genital mutilation in the Sudan: survey of the attitude of the Khartoum University students towards this practice” Sexually Transmitted Infect 79: 220-230. [crossref]

- UNICEF, “Female genital mutilation/cutting among Iraqi Kurdistan,” 2013.

- CM Little (2015) “Caring for Women Who Have Experienced Female Genital Cutting” MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 40: 291-297. [crossref]

- M. e. Nurilign A, (2015) “Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Women Towards FGM in Lejet Kebele, Dembecha Woreda, Amhara Regional state” Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 3: 21-25.

- Tag-Eldin MA, Gadallah MA, Al-Tayeb MN, Abdel-Aty M, Mansour E, et al. (2008) “Prevalence of female genital cutting among Egyptian girls” Bull World Health Organ 86: 269-274. [crossref]

- Abathun AD, Gele AA, Sundby J (2017) “Attitude Towards the Practice of Female Genital Cutting Among School Boys and Girls in Somali and Harari Regions, Eastern Ethiopia” Obstet Gynecol Int. [crossref]

- Muktar A (2013) “Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of FGM among women in Jigjiga town, Eastern Ethiopia; Cross sectional study” Gaziantep med J 19: 164-168.

- Tamire M, Molla M (2013) “Prevalence and Belief in the Continuation of Female Genital Cutting Among High School Girls: A Cross – Sectional Study in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia” BMC Public Health 5: 1120. [crossref]

- Gebremariam K, Assefa D, Weldegebreal F (2016) “Prevalence and associated factors of female genital cutting among young adult females in Jigjiga district, eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional mixed study”, International Journal of Women’s Health 8: 357-365. [crossref]

- Banks E, Meirik O, Farley T, Akande O, Bathija H, et al. (2006) “Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries” Lancet 367: 1835-1841. [crossref]

- Nurilign A, Getechew M, et’al. (2015) Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Women

towards Female Genital Mutilation in Lejet Kebele, Dembecha Woreda, Amhara

Regional State. Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 3: 21-25.