Introduction

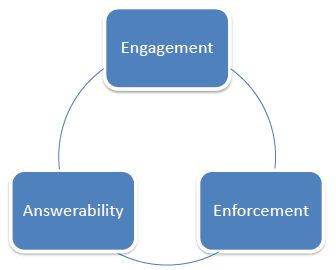

Accountability describes a relationship between a duty holder and a person or organization to whom a duty is owed. Accountability is constituted of three different elements: engagement of citizens with power holders in shaping responsibilities, answerability of power holders to citizens, and enforcement of action on power holders who fall short on their duties (Figure 1) [1].

Figure 1: Different elements of accountability

WHO states SRHR “encompasses efforts to eliminate preventable maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity, to ensure quality sexual and reproductive health services, including contraceptive services, and to address Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) and cervical cancer, violence against women and girls, and sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescents” [2].

Accountability for sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) in the context of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) entails:

- Power holders engaging citizens and SRHR organizations while framing UHC legislation, policies, plans, financing arrangements and budgets; as well citizens and SRHR organizations influencing these processes from outside,

- Citizens/clients, rights-based organizations, professional bodies and research institutions holding Ministries of Health, other relevant Ministries, and private health sector answerable for implementing SRHR sensitive UHC plans. It also entails the state holding private health sector and its own functionaries answerable internally, and

- The state or/and citizens enforcing sanctions when power holders are not able to ensure comprehensive SRHR universally and without catastrophic expenditure.

Accountability for SRHR in the context of UHC is important if Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target 3.8 and 5.6 are to be achieved. SDG target 3.8 states “Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all”. SDG 5.6 specifically refers to SRHR. It emphasizes “Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights as agreed in accordance with the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development and the Beijing Platform for Action and the outcome documents of their review conferences”. In the context of these international commitment, this paper fleshes out concepts in accountability, and show cases accountability strategies, interventions, tools, systems and mechanisms from different countries. It then pulls out lessons on making accountability for SRHR work in the context of UHC.

Unpacking Accountability

It is possible to distinguish between an accountability strategy, accountability intervention, accountability tool, accountability system, and accountability mechanism [3]. The first three are discussed in the context of SRHR, while the last two are outlined with reference to SRHR and its social determinants. “Accountability strategy” for SRHR in the context of UHC is an overarching set of interventions of governments, rights-based organizations, professional bodies, marginalized sector etc. to ensure accountability of power holders from national to local level. An “accountability intervention” refers more narrowly to the implementation of components of accountability strategy. Examples including, holding public hearings on unsafe abortions or strengthening village health committees to encourage men to adopt contraception, institutional delivery and expand access of women to iron tablets. An “accountability tool” is the use of particular accountability tool within the context of a given intervention. Examples include community scorecards of SRH services in facilities to assess qualities and public interest litigation to find out what kind of SRH services has been covered under public health insurance. Several different tools may feed into an accountability intervention. An “accountability system” for SRHR in the context of UHC may involve a “larger system” of accountability to gender and equity in general, beyond SRHR. Gender based violence protection committees, land and housing rights movement are examples. Accountability mechanisms explain what accountability strategy, instrument and tool works or does not work in what contexts.

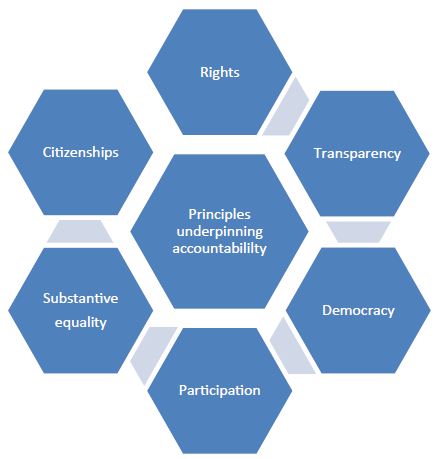

The principle of participation, transparency & democracy, citizenship & human rights and substantive equality are crucial to any accountability process, including for SRHR in the context of UHC (Figure 2). These principles are elaborated below.

- Participation: Participation can range from being “informed” to “influencing”, “agenda setting” or “decision making” on SRHR in the context of UHC. The higher order of participation is important.

- Citizenship and human rights: Citizenship refers to the state of being a member of a particular country and having rights because of it. It is distinct from the term patient or client in the context of SRH services, in that one is referring to a rights holder vis a vis the state who may make demands even when healthy. The concept of citizenship is linked to the concept of human rights inherent to all human

- Transparency and democracy: Transparency means placing all financial and public information and data including on SRHR in UHC in an easy-to-use and readily accessible manner. This allows citizens to see clearly how public servants are spending tax money and gives citizens the ability to hold their elected officials accountable. A vibrant democracy is central to transparency.

- Substantive equality: Substantive equality recognizes that everybody is not the same and the specific needs of marginalized people have to be taken into account while framing SRHR in UHC plans and delivering services. Substantive equality financing packages will allow women to access abortion facilities anywhere within a district or province to allow for privacy.

Figure 2: Principles underpinning accountability

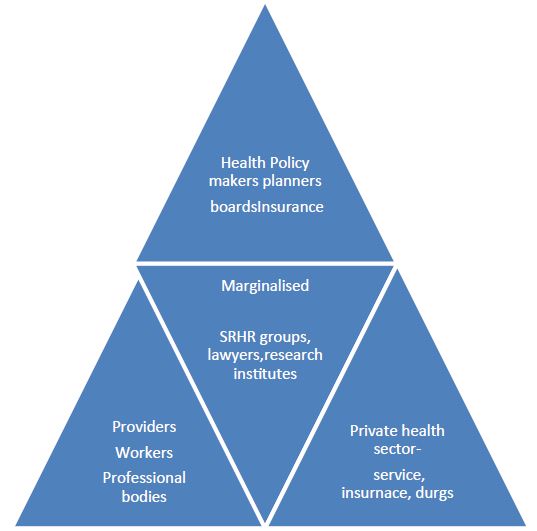

Stakeholders in Accountability for SRHR in UHC and Their Roles

Several stakeholders need to be involved in accountability processes. These include policy makers, planners, service providers, health research institutes, health economists’ donors, professional bodies, local government, private health sector, marginalized groups, unions, organizations working on SRHR, lawyers collective etc. (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Stakeholders in accountability for SRHR

Policy makers, and planners can bring the national perspective on SRHR in UHC into accountability, monitoring, evaluation and review. Donors can harness their international and regional perspectives. Involvement of professional bodies- doctors to village nurses- in accountability mechanisms ensures that technical perspectives and practical constraints that have a bearing on SRH are examined, and also ensures self-regulation towards SRHR in the context of UHC. Involvement of professional associations/unions of health workers is also important to ensure that there is no backlash against them through accountability processes. Involving health research institutes and health economists is crucial to use available research on SRHR for fostering accountability. Further, they may help to strengthen accountability interventions and tools itself from a SRHR in UHC lens. Groups working with a legal perspective on SRHR, may highlight legal measures that are required to make SRHR in UHC effective, or even go beyond like address social determinants of health. Involvement of private-not for profit health sector may also point to innovative ways of approaching SRHR in UHC.

From the bottom up, groups representing marginalized groups in terms of SRHR help to ensure that intersecting disadvantages and needs related to SRHR have been addressed the UHC and hold power holders to account in its translation. Citizens groups often draw up their own charter and could monitor the inclusion of SRHR in UHC plans and examine issues of quality of care and affordability. Local, national, and regional level SRHR organizations help generate qualitative data outside the health management information system on SRHR in UHC which can strengthen accountability. If these SRHR organizations are invited by the national government for review of progress on UHC they may help analyses public data from the vantage view of most marginalized. They can also create shadow reports before the official national level health reviews or before the Voluntary National Report on SDGs, and promote accountability from the bottom up.

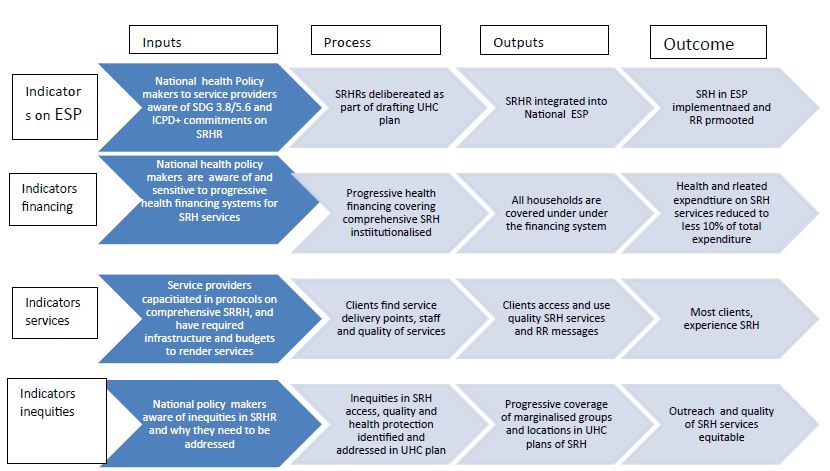

Accountability with Respect to What SRHR Indicators?

There are four set of indicators that could be used in accountability system for SRHR in the context of UHC (Figure 4).

First, the extent to which comprehensive SRH services are covered under UHC, in a progressive manner (that is, with most marginalized being given priority).

Second, the extent to which financing arrangements prevent catastrophic expenditure on these services, again with a focus on the most marginalized groups [4]. The expenditure could be on getting to the service delivery point, accessing services, accessing drugs and supplies, and (direct/indirect costs of) adherence to treatment.

Third, inequalities in access to services under UHC, in health expenditure as a percentage of total household income and inequities in SRH and RR outcomes Inequities could be across class, caste, race, ethnicity, religion, migration status, marital status, spatial location, gender orientation, sexual identity, national identity etc.

Fourth, is around quality of SRHR services and promotional activities.

All four aspects- SRH service coverage, financing arrangements, quality of care, and inequities- can be discussed in terms of input, outputs and outcomes and related indicators, leading to a matrix of indicators (Nigel et al. 2016). Figure 4 gives an illustration of such a matrix, though it cannot claim to be a comprehensive list of indicators on SRHR in UHC. Data for inputs can be collected from qualitative and quantitative studies by health research institutions and SRHR groups. Data for process indicators can be gathered through review of policy documents, facility readiness assessment and client feedback at service delivery points. Outputs require review of policy documents, interviews with clients back home of different identities and in different locations and, health financing data.

Figure 4: Accountability for SRHR in UHC – Examples of Indicators

Some sub-indicators to be looked into while focusing on service coverage and financial protection is what SRH services are covered and protected, what are not and for whom. It is important to examine if culturally sensitive services like safe and legal abortion and male sterilization, and low priority but expensive ones like sex realignment surgery are included, and whether services for adolescent girls, never married women, transwomen and transmen, women in sex work etc. are available.

Country Case Studies

Using Universal Progress Reviews to Advocate SRHR in the Context of UHC: The Case of Philippines

The Universal Progress Reviews (UPRs) were institutionalized in 2008 by the UN General Assembly as a mechanism for countries to report on their countries’ progress on human rights. The outcome of the review by reviewing countries includes a set of recommendations form the reviewing states, response of the national government and any voluntary commitment by the state on follow up of the recommendations. A total of 21,956 recommendations and voluntary commitments were made between 2008 and 2012, of which 5,720 (26%) pertained to SRHR and gender equality [5]. Seventy-seven of these were formally accepted by the states. There were 12 sessions held during this period, and the proportion of recommendations and voluntary commitments on SRHR and gender equality increased form 20% in the first session to 33% in the last session. Issues of lifting of reservations, gender-based violence, discrimination based on sexual orientation, maternal mortality, female genital mortality, and morbidity received attention in the UPRs [5].

The potential and challenges in using the UPR to promote SRHR is illustrated by the case of Philippines, wherein Family Planning Organization of the Philippines and Sexual Rights Institute lobbied in the UPR, 2012 for a comprehensive SRH law and policy, legalization of abortion age appropriate sexuality education, better contraceptive services, sexuality education, posting adequate number of midwives, and conduct of maternal death reviews [6]. The reviewing countries recommended passing of Reproductive Health law, legislation protecting rights of sexual and gender minorities, access to universal SRH services, enrolling poor in health insurance, addressing gender-based violence, strengthening family planning services and providing abortion for rape, incest, and risk to life of mothers [7]. A Reproductive Health Bill was passed by the Assembly of Philippines in 2012, but it has been as the pressure from the Church which is high in some provinces, and implementation is devolved. Contraception for adolescent is far from reality. Further, budget for contraception has been reduced and but parental/spousal consent is still required in some provinces, and emergency contraception is not easily available [8].

National Health Insurance: Weaving in SRH and Progressive Coverage in Zambia

The government of Zambia established UHC as a priority in its most recent National Health Strategic Plan (NHSP 2017-2021). In September 2017, the government developed a 10-year national health financing strategy and the mandatory National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS). A National Health Insurance Act was then in April 2018 and a National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) with a board was formed to manage the insurance scheme with an ambitious target of 100% coverage. In the early stages of designing the scheme there was little participation of SRHR groups. It is in this context that Population Action International and national organization Center for Reproductive Health Education came together in 2018 to organize a two-day workshop for 20 advocacy and service delivery civil society organizations, academicians, and representatives of medical associations. The objective of the workshop was to understand Zambia’s UHC financing policy reforms, their implications for SRH services, drugs and supplies and to develop an advocacy strategy for constructive engagement of civil society actors with the Ministry of Health and National Health Insurance Authority. A Ministry of Health official and a Zambian legal expert participated in the workshop, helping to understand Zambia’s health financing and legal landscapes, and timelines and functioning of the National Health Insurance Authority governing body and fund. Population Action International provided technical inputs as health financing and National Health Insurance Scheme was new to the civil society groups. It was also able to harvest relevant experience from other countries. The workshop examined whether National Health Insurance Scheme protects the existing National Health strategy – which prioritizes maternal health, adolescent sexual health education, contraception, Sexually Transmitted Infections, human immunodeficiency virus, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, cervical cancer screening and health services for survivors of violence. Three advocacy agendas emerged through the workshop: a) gather evidence on of out of pocket spending on SRH services and commodities and to advocate that comprehensive SRH is included in the essential service package b) include a civil society representative in the board of National Health Insurance Authority and its technical committees c) Help achieve communications objectives of National Health Insurance Scheme, in particular to reach information to women and girls in the informal sector, While the exact impact is not known of this advocacy, sexual and reproductive health organizations are being consulted by the government in deciding service package and they are represented in the National Health Insurance Authority committees, though not Board. Information is reaching women and girls in the informal sector on the scheme [9]. Population Action International is also intervening in India, Ghana, Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda on UHC to strengthen integration of SRHR into package and financing.

Political Accountability to SRH through Interparliamentary Forums: The Case of Eswatini

Southern and Eastern African Parliamentary Alliance of Committees of Health (SEAPACOH) acts as a forum to strengthen political accountability to SRH in the region. Not only Parliamentarian, but also civil society and regional organizations attend the meetings of SEAPACOH to exchange information, facilitate policy dialogue, and identify concrete actions to advance health equity and sexual and reproductive health in the region. One of the countries that presented in the 2011 meeting of SEAPACOH was Swaziland (now called Eswatini). The Parliamentarian form Swaziland observed that the country had put in place an SRH strategic plan (2008-2015), a National Condom Strategy for men and women and a strategy to integrate SRH and HIV interventions. Nevertheless, he/she observed that implementation has been constrained by absence of SRH Policy, difficulty in mobilizing financial support and over prioritization of HIV over other SRH needs [10]. Comments then followed from the larger SEAPCOH forum on the need for the country to put in place overarching comprehensive SRH policy, strategies to accelerate reduction in maternal mortality, strengthen maternity waiting huts or homes near the hospital. Information on how far these comments have been acted on is not clear, and whether integrated into essential service packages and financing under UHC plans.

The UHC Card: The Case of Argentina

Argentina, an upper-middle-income country, has a well-developed health system, particularly comparing to standards of low- and middle-income countries. Although all inhabitants of Argentina are entitled to receive health carefree of charge in public facilities, UHC is still aspirational rather than actual. Quality of care is still an issue and inequalities in access and outcomes between rich and poor provinces. Variations in infant mortality rate, maternal mortality rate and cervical cancer screening and treatment prevail. To bridge such gaps officials from the Ministry of Health evolved a dashboard of key indicators that would be used to monitor UHC, called the UHC score card. Sixty-five indicators at primary health care level were selected of a total of 166 indicators identified initially. These UHC indicators were classified into five domains: system, inputs, service delivery, results and impact. Of the 65 indicators the ones that could have a bearing on SRH in the context of UHC are given in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Indicators across domains pertaining to SRH in Argentina UHC scorecard

| Domains | Indicators |

| 1. System | • Proportion of people with exclusive public coverage that have access to basic health services

• Proportion of people with exclusive public coverage assigned to a primary care facility • Proportion of primary care facilities with geographical responsibility defined • Proportion of primary care facilities that bill to social security • Current primary health-care expenditure per capita |

| Inputs | Nurse density (per 10 000 population)

• Primary care doctor density (per 10 000 population) • Health-care facility density (per 100 000 population) • Vaccine supply according to risk groups • Essential drugs availability according to target population |

| Service delivery | • Barriers to access due to cost of treatment

• Barriers to access due to distance • Dropout rate of treatment Success rate of treatment

|

| Results | • Rate of women aged 25–64 years with cervical cancer screening

• Women aged 25–64 years that have started treatment for high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions or invasive cervical cancer

|

| Impact | • Adult mortality from non-communicable diseases

• Maternal mortality • Neonatal mortality • Rate of hospitalization for primary-care-sensitive conditions |

These indicators could be more SRH and RR aware, like availability of essential drugs related to SRH morbidity could be included under inputs, barriers to access due to health providers attitude (like on provision of safe and legal abortion) could be included under ‘service delivery’, rate of adolescents who get contraception on demand could be included under results and indicators like reduction in anemia amongst women of reproductive age could be included under impact.

Near Miss Maternal Case Review: Armenia, Georgia, Latvia, Republic of Moldova and Uzbekistan

WHO has been advocating “near miss maternal case reviews” since 2004, and guidelines were evolved in 2015. As there are less legal implications of near miss maternal case reviews than maternal death audits, the reviews will lead to more honest analysis and recommendations. Further the user’s views can potentially be secured unlike the case of maternal deaths. The WHO 2015 checklist for near miss maternal case reviews consisted of 50 items, grouped in 11 domains (internal organisation, ground rules, case identification, case presentation, inclusion of users’ views, case analysis, recommendations, follow up, documentation and diffusion and ensuring quality of near miss maternal case reviews). This checklist was used in the review of near miss maternal case reviews in the five countries. The sources of information for the assessment include direct observation of one or more near miss maternal case reviews sessions, discussion with participants, coordinators and managers and review of documents [11]. The findings from the review suggest that the quality of the near miss maternal case reviews implementation was heterogeneous among different domains, different countries, and within the same country. Overall, the first part of the audit cycle (from case identification to analysis) was performed on most indicators. However, users’ views were rarely secured. The second part (developing recommendations, implementing them and ensuring quality) was poorly performed- in particular implementation. There were inter country and intra country variations. In the ex-Soviet countries, hierarchies prevailed and even midwives were not involved. The tendency was for the doctors to affix blame on one staff, rather than look at health system issues and coming with organizational solutions. There were intra country variations too. Each country had at least one champion facility, where quality of the near miss maternal case reviews cycle (around one and a half years) was well completed from analysis to implementing recommendations. In the context of UHC, the implication of health financing policies needs to be examined in maternal health service access, utilization and outcomes.

Monitoring of Insurance Schemes from an SRH Lens: Mexico and India

In Mexico, the maternal mortality rate is 60 per 100,000 live births. While this is lower than many African counties, these deaths are concentrated among rural indigenous women and Afro-descendant women living in extreme poverty. The World Bank-funded “Coverage Extension Program” target marginalized communities and include maternal health among their priorities. In addition, there is the “Fair Start in Life” (APV) program which was specifically designed to address maternal and infant health. Fundar (an independent and interdisciplinary organization devoted to research issues) and its partners’ analysis of fund allocation of APV revealed that the maternal health budget was insignificant and that per capita expenditures were lowest in the regions of the country with the highest concentration of poverty. Furthermore, targeted programs did not improve health infrastructure or provide emergency obstetric care and mainly focused on prenatal care. Fundar and its partners also examined the government ‘s Seguro Popular or popular health insurance. On the positive side, the insurance program receives the majority of its funding from the federal government, with small contribution from the states. This reduces inequalities across states and between employed and unemployed. However, detailed budget information that had been previously available became hidden within huge budget categories. Seguro Popular did not initially include emergency obstetric care services. The coalition working on maternal mortality undertook the task of pricing the provision of basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care and demonstrated its viability and life-saving relevance. As a result, a series of emergency obstetric care-related services and interventions were ultimately included in the program. Other areas the coalition advocated was utilisation of budget earmarked for infrastructure between 2004 to 2007, as 70% of funds for infrastructure was unspent. Through the analysis and advocacy strategies of Fundar and its partners, the profile of maternal mortality has been raised, and it is had become a public issue related social justice, gender, class and race. Allies in the Ministry of Health and Gender Equality Commission in Congress helped push emergency obstetric care. On the other hand, budget transparency varied across regimes and posed challenges [12].

Private Health Sector Accountability to Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health

The government policies in India seek to engage the private sector through public-private partnerships, insurance, and other schemes, including for reproductive, maternal, new-born, and child health (RMNCH). Through the USAID supported Vriddhi project, John Snow Inc (JSI), India conducted an assessment of RMNCH service delivery in the private sector [13]. Using a mixed-methods approach, the assessment gathered information from over 300 respondents, including facility-based private providers; professional associations; pregnant women and mothers with children under five years of age; government representatives at the national, state, and district levels; and social enterprises in 7 districts across 6 states, namely Delhi, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Uttarakhand. The study revealed that only 37 of 87 Inpatient Departments had legal registration to provide medical services. Very few facilities were accredited under recognized systems. None of the facilities provided all RMNCH services as per global or national guidelines. There were gaps in knowledge of contemporary treatment guidelines. The study also found that only 20 of 67 of facilities provided the entire range of RMNCH services. The most commonly provided service was delivery care. The number of reported caesarean sections was much higher than expected, and many did not provide newborn care services. Private providers had reservations about participating in a government-supported health insurance program for the poor, citing that the program does not cover actual costs and that reimbursement is often delayed. In contrast, government representatives suspected that private providers submitted inflated bills and wrongful claims under the program. At the same time the study found that pregnant women often prefer to seek treatment from private providers. Almost all clients highlighted ease of access, time given by providers, better nursing facilities and cleanliness as top reason for private sector preference. However, clients revealed a preference for government facilities if doctors were accessible around-the-clock, as better counselling services were provided on RMNCH. The results of the assessment and recommendations were discussed at a national consultation with public and private sector stakeholders in 2017. The recommendations include establishing public-private partnerships cells at state level and building capacities of private medical professionals on RMNCH and government-endorsed RMNCH guidelines and protocols. Seven thousand medical practitioners were trained through the process.

Community and Service Provider Accountability to SRHR

SRHRs are co-produced/fulfilled by health providers and communities- comprising of marginalized citizens and gate keepers. The Center for Health and Social Justice (CHSJ), an Indian health rights-based organization, formed father’s groups and adolescent boys’ groups with the objective of fostering them to be responsible partners and caring fathers/brothers. The larger goal was to promote women’s rights. As of 2018 this initiative of CHSJ was operational in five states of India. In the state of Jharkhand, marginalized men and women (form indigenous groups, Dalits, women headed households) came together with local government representations, front line health and nutrition workers and interested schoolteachers to prioritize problems related to health and its social determinants through a secret ballot. On the basis of this participatory exercise, a citizen’s charter was evolved in 30 villages in three districts of the state of Jharkhand. A unique feature was that the charter was on what men would do to foster women and children’s health and empowerment. The charter included men’s commitment to monitor health and nutrition services and public distribution system along with women’s groups, encourage women and children to make use of the anganwadi centers (centers for early childhood development and care of pregnant and breast feeding mothers) centers and health sub centers, accompany pregnant women go to health facilities for ANC and institutional delivery, taking children for immunization, (men) adopting contraceptive methods, ending child marriage, and preventing acts of violence on women and children. The charter is hung in prominent places like tea shops, anganwadi centers and schools. However, the use of the chart for actually strengthening accountability of men or service providers varies across villages, dependent on vibrancy of women’s and fathers’ groups. In some villages, there were reports of reduction in domestic violence, men helping in housework, and accompanying women and children to facilities. However, issues like access to safe abortion, screening of reproductive cancers, health referral in instances of gender-based violence or adolescent access to SRH services did not appear in the charter [14-17]. Neither did issues of health financing and monitoring expenditure on health as a percentage of total health expenditure.

Key Lessons and Messages

- Accountability for SRHR in UHC (SDG 3.8) needs to be seen along with accountability to SRHR in general (SDG 5). When SRHR policy and legislation is weak, like the case of Philippines, accountability to SRHR in UHC cannot be promoted.

- Accountability for SRHR in the context of UHC entails attention to SRHR in essential service package, access to marginalized, quality of SRH services, and issues of health financing and avoidance of catastrophic expenditure. The case study on health insurance in Mexico is a good illustration of this lesson.

- Examples of accountability for SRHR as answerability are more common than as enforcement and engagement (Table 2).

- There are many accountability interventions and instruments for SRHR. These include involvement of international to local women’s groups in monitoring, implementing UHC score cards and near miss maternal reviews, using UPRs to press for accountability, analysis of health expenditure and financing data, getting into health insurance committees and consultations. No one size fits all situations, and a strategy/system combining mix of interventions and instruments need to be adopted.

- Few of the examples of strengthening accountability for SRHR are in the context of UHC. This is particularly true at the community level. There is a need to demystify UHC and take it to community level, like what is happening in Mexico.

- There are few examples of ways in which controversial or sensitive SRH services were brought into the UHC through accountability strategies, interventions and instruments. This includes safe and legal abortion, treatment for violence etc. There are more examples related to maternal and child health. However, the Mexico case study illustrates how even emergency obstetric care was not included till it was provided “financially” viable.

- There are examples of UHC plans reaching MCH services to the poor, but few to stigmatized groups like sex workers, sexual and gender minorities. The Argentina scorecard is an example.

- There are more examples of citizens groups monitoring or holding state accountable on SRH in the context of UHC but few on strengthening private sector accountable to SRHR in the context of UHC. The Vriddhi project example from India is an exception. This is also true of holding private insurance and pharmaceutical industries to account for SRHR.

- SRHR in the context of UHC requires that gender and social norms in society change too. Men, community leaders and local governments need to be held accountable as well. The CHSJ example from India illustrates this.

- Many of the examples pertain to “surrogates” for marginalized – civil society actors or donors- holding national governments and service providers to account, but not the marginalized. The challenge is to reverse this.

- Higher middle-income countries are able to afford services in essential service package which some of the lower income/lower middle-income countries cannot. It is hence important to track donor funding to SRHR. Further it is crucial to monitor funding to health by government as part of GDP, and not just SRHR in UHC. The politics of budget allocation is crucial.

- Democratic framework a must to strengthen accountability for SRHR in UHC. It cannot be implemented from top (Eastern Europe/Central Asia case study). At the same time while working with local elected government is important, they also hold discriminatory views, and need to be challenges (the Philippines case study).

Table 2: Examples of accountability for SRHR sector

|

Country/focus |

Accountability as engagement |

Accountability as answerability |

Accountability as enforcement |

Mode of accountability |

Instruments |

| 1Philippines- Weaving SRH Legislation and policy | Engagement of civil society with Universal Progress Reviews to advocate legal abortion, contraception and sexuality education | Monitoring provision of contraception and abortion budget allocated | Intervention | Lobbying at Universal Progress Reviews

Monitoring

|

|

| 2 Accountability in SRH sector through interparliamentary forums

|

Southern and Eastern African Parliamentary Alliance of Committees of Health monitoring implementation of SRH plan and condom strategy. | Intervention | Monitoring by Inter Parliamentary Committee on Health | ||

| 3.Zambia- Weaving SRH and progressive coverage insurance

|

Engagement of SRHR groups with national health insurance authority (NHIA) to prioritize SRH services for informal sector | SRHR groups represented in NHIA committees | Intervention | Lobbying nationally

Capacity building of SRHR groups on health financing

Representation in NHIA committee |

|

| 4. Mexico – Monitoring health insurance schemes

|

Evaluation of Fair start programmed and health insurance programmed; highlighting poor attention to EmOC, outreach to indigenous | Evidence to show viability of EmOC in insurance; and its subsequent inclusion | Intervention

|

Cost Benefit analysis

Lobbying |

|

| 5. Argentina- SRH integrated UHC scorecard

|

Monitoring inputs, service delivery, results and impact- includes maternal health and reproductive cancer | Instrument | UHC score card | ||

| 6. Armenia, Georgia, Latvia, Republic of Moldova and Uzbekistan –

Near miss maternal case review

|

Evaluation of “Near miss maternal care reviews” using checklist revealed the tendency to fix blame, not involve midwives and users, and not draw systemic lessons” | Instrument | Evaluation

Check list |

||

| 7. India: Private health sector reproductive, accountability in maternal, newborn, and child health (RMNCH)

|

An assessment of RMNCH service in private facilities, capacity building of private providers based on findings – including on protocols on RMNCH[1] | Intervention | Review

Capacity building

|

||

| 8. India: Men’s and service providers’ accountability in SRHR

|

Implementation of citizen’s charter on men’s role in MCH, contraception, reducing gender-based violence (GBV) and monitoring inter sectoral services | Intervention

Eco system

|

Implementing charter on men’s responsibility for care of women and children, making local providers accountable and preventing GBV |

To sum up this paper argues that accountability for SRHR and accountability for UHC are both important. Further, accountability for addressing social determinants of SRHR is also crucial, including in the context of disasters, conflicts and pandemics. Accountability for SRHR to policy makers and planners is more common than to marginalized (in addressing intersectional barriers). Accountability for sensitive SRHR issues is less like accountability to provide safe and legal abortion services and health services for gender-based violence and making sure these are part of essential service package. On the other hand, accountability to bring down fertility is higher. Accountability for SRH Services within UHC for controversial groups like adolescents, sex workers, transgenders, religious minorities, and migrants is limited. Accountability systems, strategies, interventions and tools can be seen more for answerability, than enforcement of sanctions (for lack of accountability) and somewhere in between for engagement of citizens in policy making, planning and budgeting. Few examples exist of accountability of private health services and insurance for SRHR. Democracy, active citizenship and resources are a must for accountability for SRHR in the context of UHC. Ultimately accountability to SRHR in the context of UHC is about the tilting the balance of power towards marginalised, public health sector and front-line workers.

References

- Caseley J (2003) Blocked Drains and open minds: multiple accountability relationships and improved service delivery performance in Indian city. Institute of Development Studies (IDS) Working Paper 211.

- World Health Organisation (2014), Sexual and reproductive health and rights: a global development, health and human rights priority, Comment, Lancet 384: e30-1. [crossref]

- Belle Van Sara, Vicky Boydell, Asha S George, Derrick W Brinkerhof, Rajat Khosla (2018) “Broadening Understanding of Accountability Ecosystems in Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: A Systematic Review” edited by J. P. van Wouwe 13: e0196788. [crossref]

- O’Neill K, Viswanathan K, Celades E, Boerma T (2016) Monitoring, evaluation and review of national health policies, strategies and plans. Strategizing national health in the 21st century: a handbook. Geneva: World Health Organization 1-39.

- Gilmore K, Mora L, Barragues A, Mikkelsen IK. (2015) The universal periodic review: A platform for dialogue, accountability, and change on sexual and reproductive health and rights. Health & Hum. Rts. J 17: 167. [crossref]

- Family Planning Organisation of the Philippines and Sexual Reproductive Rights Institute, 2012

- (2012) UPR of the Philippines 2nd Cycle 13th Session, Matrix of Recommendations https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/UPR/Pages/PHindex.aspx Last accessed 20th February, 2020.

- Lloyd, Cristyn 2018, Whatever happened to The Philippines’ reproductive health law.

- Population Action International, (2019) Seizing the Moment: How Zambian Sexual and Reproductive Health Advocates are Accelerating Progress on Universal Health Coverage Finanicng.

- Ministry of Health, 2011, Presentation of the portfolio health committee from the parliament ofSwaziland, SEAPACOH meeting Kampala, Uganda.

- Bacci A, Hodorogea S, Khachatryan H, et al. (2018) What is the quality of the maternal near-miss case reviews in WHO European Region? Cross-sectional study in Armenia, Georgia, Latvia, Republic of Moldova and Uzbekistan. BMJ Open 8: e017696. [crossref]

- International Budget Partnership and the International Initiative on Maternal Mortality and Human Rights (2009), THE MISSING LINK Applied budget work as a tool to hold governments accountable for maternal mortality reduction commitments, USA.

- John Snow Inc, (2019) News and Stories: Engaging the Private Sector to Improve Reproductive Maternal and Reproductive Health in India.

- Murthy RK (2018) New Frontiers in working towards gender equality and child rights? Evaluation of the project.

- UPR Submission on the Right to Sexual and Reproductive Health in the Philippines 13th Session of the Universal Periodic Review – Philippines – June 2012.

- Population Action International, 2019 UHC Country Level Action, Last accessed 20th February, 2020.

- Rubinstein, Adolfo Mariela Barani, Analía S Lopez c2018) Quality first for effective universal health coverage in low-income and middle-income countries 6: e1142-e1143. [crossref]