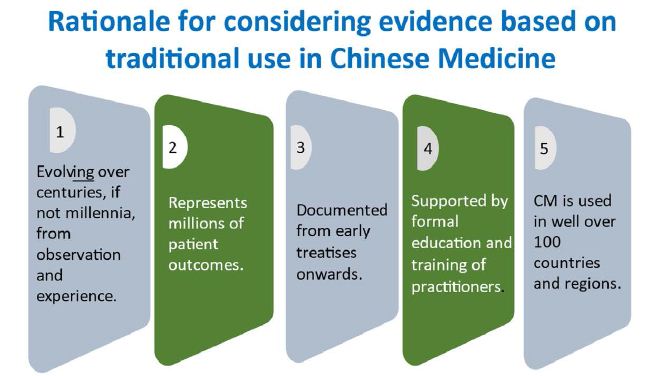

For reasons including affordability, accessibility, cultural heritage and health benefits, traditional medicines are still important contributors to health care. As the regulation of medicines becomes increasingly evidence and risk based, regulators have the challenge of dealing with the role of traditional use evidence in assessing the safety and efficacy of traditional medicines. Regulators must protect the consumer while also respecting the rights of consumers to have access as far as possible to medicines of their choice. Evidence for the safety and efficacy of traditionally used medicines is based largely on observation and experience over extended periods, sometimes gained over centuries of use. If Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is used as an example, the evidence has evolved over millennia of use, and is still evolving, and the information is passed on through documentation such as in treatises and the education and training of practitioners (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Rationale for considering evidence based on traditional use in Chinese medicine.

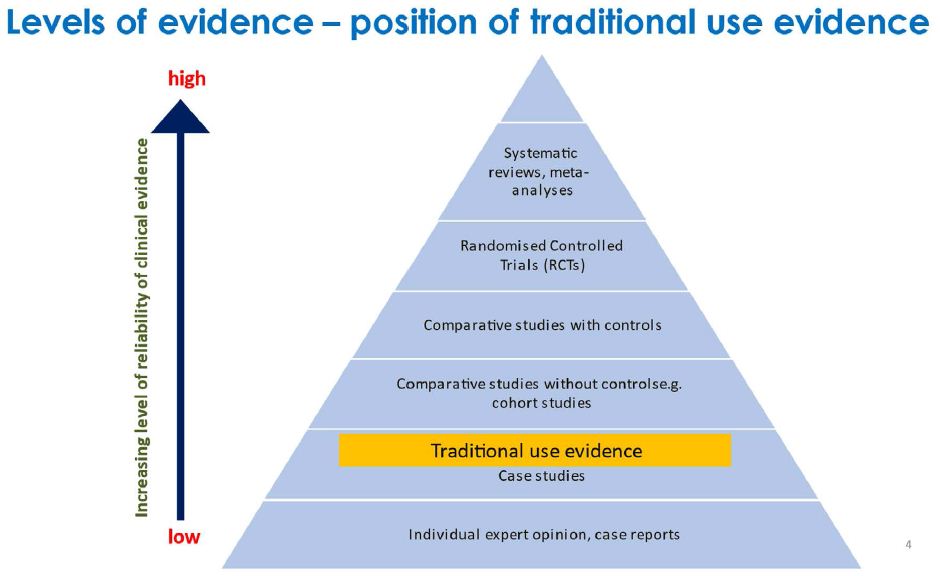

However, in recent times more reliable scientific methods for establishing the safety and efficacy of medicines and medical treatments have been developed. While there is considerable activity by industry and researchers in using these newer methods to substantiate the safety and efficacy of traditional medicines, evidence of traditional use will still be used to justify the supply of many of traditional medicines due to their compositional complexity such as from using raw herbs and the lack of incentives to conduct expensive clinical studies when the intellectual property from studies on natural materials may not be able to be protected. A dilemma is that traditional use evidence, while an important source of information, ranks quite lowly on the scale of reliability of evidence (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Levels of evidence – position of traditional use evidence.

The challenge for regulators therefore is how to apply adequate care to protect consumers from unsafe or ineffective medicines without denying access to traditional medicines. While some countries have avoided the issue by classifying such products as foods or unregulated products, Australia has taken a pragmatic approach towards their risk management for both the supply of proprietary medicines and the individualised formulation of prescriptions by practitioners.

Accommodating Traditional Use Evidence in Risk-based Regulation of Proprietary Medicines

Premarket Regulation

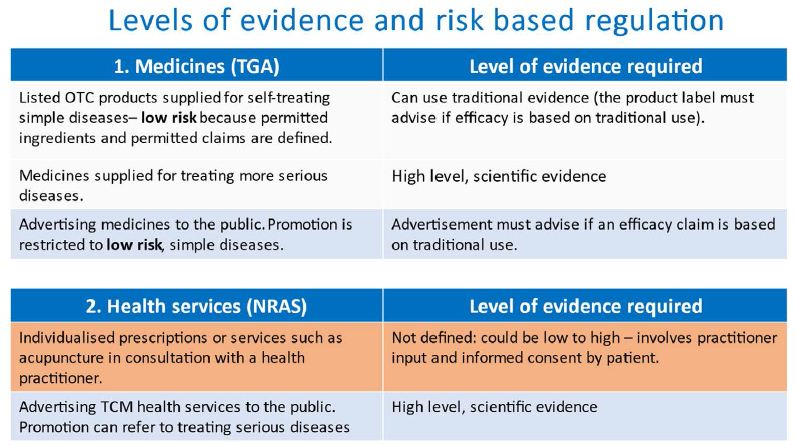

In Australia, medicines other than some very low risk classes, must be entered onto an Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) based on to their acceptable quality, safety and efficacy before they can be supplied into the market.All medicines on the ARTG are expected to be manufactured in compliance with Good Manufacturing Practice by licensed manufacturers. For dealing with quality and safety, there are two levels of entry into the ARTG; ‘listed’ medicines for lower risk products and ‘registered’ medicines for higher risk products. Any medicine whose safety and efficacy are based on traditional use evidence is classified as a listed medicine and can only contain active ingredients in a defined list for which safety is well established [1], is limited to therapeutic claims in a defined list which mainly refer to the treatment of minor, self-limiting conditions [2] and the supplier must be able to provide the traditional use evidence upon which the therapeutic claims are based. The product label must indicate that the intended purpose of the medicine is based on traditional use. If the supplier wishes to make more substantial therapeutic claims outside this framework, the justification must be based on scientific evidence.

Post Market Regulation

The channels of supply of medicines in the marketplace is determined through a Standard for the Uniform Scheduling of Medicines and Poisons (SUSMP) [3] which restricts the supply of certain substances to the prescription of primarily western medical practitioners or to supply through a pharmacy or to supply directly by a pharmacist. Most proprietary traditional medicines because of the premarket controls to minimise their risk are unscheduled thus allowing unrestricted supply. Advertising of non-prescription medicines to the public is limited to their therapeutic claims included in the ARTG and must indicate that the claims are based on traditional use evidence [4]. The regulator (the Therapeutic Goods Administration) monitors and responds to adverse events to medicines.

Accommodating Traditional Use Evidence in the Regulation of Traditional Medicine Practitioners

TCM practitioners are a nationally regulated, allied health profession under the jurisdiction of the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme (NRAS) [5]. They must be registered to practice subject to similar educational and professional practice standards as other important health professions such as practitioners in medicine, nursing, dentistry and pharmacy. While the level of evidence to support professional health services provided by the practitioner to a patient is not defined in law, individualised prescriptions based on traditionally used ingredients cannot contain ingredients restricted by the SUSMP and the practitioner’s registration standards require that appropriate informed consent is given by the patient after receiving information about their intended treatment and any associated risks. While advertising of professional health services to the public can refer to more substantial medical conditions, the advertising must be able to be supported by scientific evidence, not just traditional evidence. This is because advertising to the public is providing information usually without any consultation with the practitioner. Traditional health professions other than TCM come under the regulation of each Australian State or Territory. These practitioners operate via negative licensing whereby they can practise without being registered but are subject to a national Code of Conduct for Health Care Workers [6] which contains similar principles for practice and advertising to those required for health professions subject to the NRAS. There are strong complaint systems in place whereby anyone can submit concerns about individual practitioners (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Levels of evidence and risk based regulation.

Conclusion

The primary role of health regulators is to apply a regulatory scheme that moderates risks sufficiently to protect consumers without inappropriate hindrance to access or to industry. This paper describes the procedures used in Australia to moderate risks when relying on evidence based on traditional use for the efficacy and safety of traditional medicines.

References

- Therapeutic Goods (Permissible Ingredients) Determination: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2021L01108

- Therapeutic Goods (Permissible Indications) Determination, tables 14 and 15: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2021L00056

- Standard for the Uniform Scheduling of Medicines and Poisons (SUSMP): https://www.tga.gov.au/publications/poisons-standard-susmp

- Therapeutic Good Advertising Code: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2021C00845

- National Registration and Accreditation Scheme (NRAS): https://www.coaghealthcouncil.gov.au/NRAS

- National Code of Conduct for Health Care Workers: https://www.coaghealthcouncil.gov.au/NationalCodeOfConductForHealthCareWorkers