Abstract

We present a new, systematized way to teach critical thinking, using AI (artificial intelligence) incorporated into a research tool created for a newly emerging science, Mind Genomics, that is concerned with how people respond to ideas concerning everyday experiences. Mind Genomics methodology requires the researcher to develop four questions which ‘tell a story,’ and for each question to provide four alternative answers. Previous studies showed that many users experienced difficulty creating the questions. To overcome this problem, Mind Genomics incorporates AI through the mechanism of the Idea Coach. This mechanism allows the researcher to describe the problem being addressed, and then generates 15 questions the researcher evaluates and chooses for returns with 15 questions during the course of setting up the study’s story. Idea Coach provides additional analyses on the questions returned to reveal deeper structure and stimulate critical thinking by the researcher. We demonstrate the capabilities of the process by comparing the results for ‘food sustainability’ for people who are defined to be poverty stricken, first in the United States, and then in Ghana, and finally in Egypt. The effort requires approximately 10 minutes in total and is scalable for purposes of education and practical use.

Introduction: The Importance of Critical Thinking to Solve Problems

In order to address issues facing humanity, such as sustainability, it is important to be able to think clearly about the nature of the problem, and from there proceed to solutions. The importance of critical thinking cannot be underestimated, most apparently in education [1,2], but also in other areas, such as dentistry [3], not to mentioned the very obvious importance of critical thinking in areas where there are opposing parties confronting each other with the weapons of knowledge and thinking, such as the law [4]. The very idea of dealing with the United Nations’ (UN) 24 defined Global Issues (United Nations, undated) calls into play the need to understand and then deal with the problem. Critical thinking, or its absence has been recognized as a key feature in the solution of these problems. From the UN’s perspective, their 24 issues need to be addressed continually over time, strongly suggesting that the need for critical thinking is not limited in time but needs to be engaged with through time.

In today’s world, critical thinking is recognized as important for society [5]. The key question is not the recognition of critical thinking, but rather how to encourage it in a way which itself is sustainable, in a way which is cost-effective, scalable, and productive in terms of what it generates. To the degree that one can accelerate critical thinking, and even more so to focus critical thinking on a problem, one will most likely be successful . Finally, if such critical thinking can be aided by technical aids, viz., TACT (Technical Aids to Creative Thought), there is a greater chance of success. The notion of the aforementioned approach TACT was first introduced to the senior author HRM by the late professor Anthony Oettinger of Harvard University in 1965, almost 60 years ago. This paper shows how today’s AI can become a significant contributor to TACT, and especially to critical thinking about UN based problems, this one being food sustainability [6].

The topic of food sustainability is just one of many different topics of the United Nations, but one seeing insufficient progress (UN undated). From the point of view of behavioral science, how does one communicate issues regarding food sustainability? And how does one move beyond the general topic to specific topics? It may well be that with years of experience in a topic the questions become easier, but what about the issue of individuals wanting to explore the topic but individuals without deep professional experience? Is it possible to create a system using AI which can teach in a manner best called Socratic, i.e., a system which teaches by laying out different questions that a person could ask about a topic?

The Contribution of Mind Genomics to Critical Thinking about a Problem

During the past 30 years, researchers have begun to explore the way people think about the world of the everyday. The approach has been embodied in an emerging science called Mind Genomics (REF). The foundation of Mind Genomics is the belief that we are best able to understand how people think about a topic by presenting them with combinations of ideas, and instructing these people to rate the combination of ideas on a particular rating scale, such scales as relevance to them, interest to them, perceived solvability, etc. The use of combinations of ideas is what is new, these combinations created in systematic manner by an underlying structure called an experimental design. The respondent who participates does not have to consciously think about what is important, but rather do something that is done every day, namely choose or better ‘rate’ the combinations on a scale. The analysis of the relation between what is presented and what is rated, usually through statistics (e.g., regression) ends up showing what is important.

The process has been used extensively to uncover the way people think about social problems [7], legal issues [8], etc.. The process is simple, quick and easy to do, prevents guessing, and ends up coming up with answers to problems.

The important thing here is that the researcher has to ask questions, provide answers, and then the computer program matches the answers together into small groups, vignettes, presents these to the respondent, who has to rate he group or the combination.

Of interest here is the front end of the process, namely, how to ask the right question. It is asking questions which has proved to be the stumbling block for Mind Genomics, since its founding in 1993 (REF). Again, and again researchers have request help to formulate the studies. It is no exaggeration to state that the creation of questions which tell a story has become one of the stumbling blocks to the adoption of Mind Genomics.

Early efforts to ameliorate the problem involved work sessions, where a group of experts would discuss the problem. Although one might surmise that a group of experts in a room certainly could come up with questions, the opposite was true. What emerged was irritation, frustration, and the observation that the experts attending either could not agree on a question, or in fact could even suggest one. More than a handful of opportunities to do a Mind Genomics project simply evaporated at this point, with a great deal of disappointment and anger covering what might have been professional embarrassment. All would not be lot, however, as many of the researchers who had had experienced continued to soldier on, finding the process relatively straightforward. Those who continued refused to let the perfect get in the way of the good. This experience parallels what has been previously reported, namely that people can ask good questions, but they need a ‘boost’ early on [9].

The Contribution of AI in 2023

The announcement of AI by Open AI in the early months of 2023 proved to provide the technology which would cut the Gordian knot of frustration. Rather than having people have to ‘think’ through the answer to the problem with all of the issues which would ensue, it appeared to be quite easy to write a query about a topic and have the Mind Genomics process come up with questions to address that query. It was, indeed, far more enjoyable to change the ingoing query, and watch the questions come pouring out. It would be this process, a ‘box for queries’ followed by a standardized report, which would make the development fun to do.

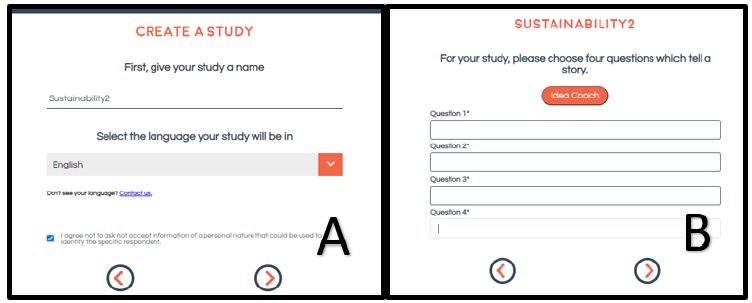

Figure 1 shows what confronted the researcher before the advent of AI, namely an introduction page which required the researcher to name the study, followed immediately by a dauntingly empty page, requesting the research to provide our questions which tell a story. The researcher has the option to invoke AI for help by pressing the Idea Coach button.

Figure 1: Panel A shows the first screen, requiring the respondent to name the study. Panel B shows the second screen, presenting the four questions to be provided by the respondent.

Results Emerging Immediately and After AI Summarization

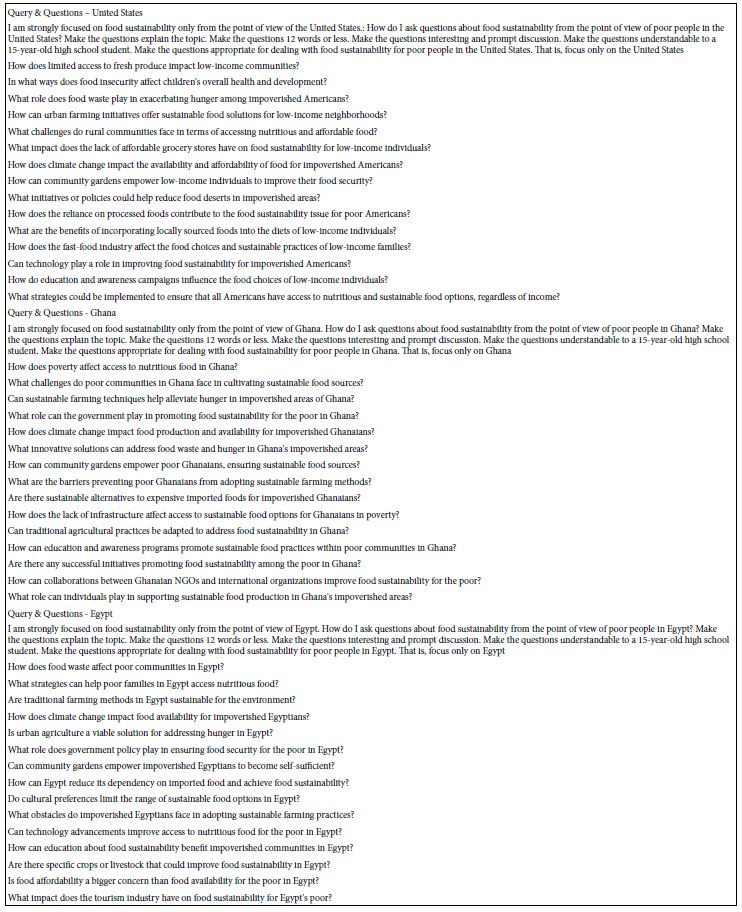

The next set of tables shows the questions submitted through the query to Idea Coach, the immediate set of 15 questions returned within 5-15 seconds. Later on, we will see the results after AI summarization has been invoked on the different set of questions.

In the typical use of Mind Genomics, the researcher often ends up submitting the squib to Idea Coach from a minimum of one time, but more typically 3-5 times, occasionally modifying the squib, but often simply piling up different questions. These different questions, 15 per page, provide a valuable resource of understanding the topic through the question. Typically, about 2/3 of the questions are different from those obtained just before, but over repeated efforts many of the questions will repeat.

Table 1 shows the first set of 15 questions for each of three countries, as submitted to Idea Coach. Note that the squib presented to Idea Coach is only slightly different for each country, that difference being only the name of the country. The result, however, ends up being 15 quite different questions for each country, questions which appear to be appropriate for the country. It is important to emphasize here that the ‘task’ of AI is to ask questions, not to provide factual information. Thus, the issue of factual information is not relevant here The goal is to drive thinking.

Table 1: Query & Questions for United States, Ghana and Egypt. These 15 questions emerged 10-15 seconds after the query was submitted to Idea Coach.

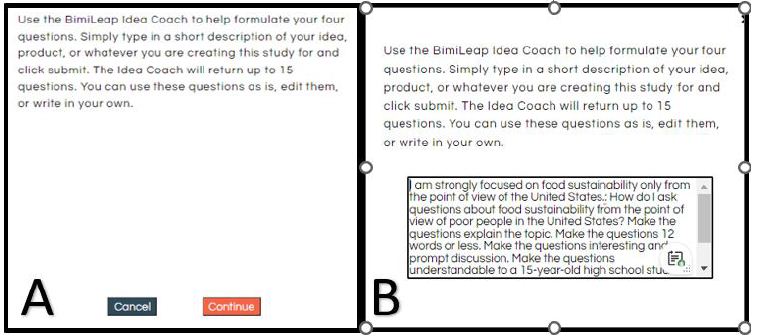

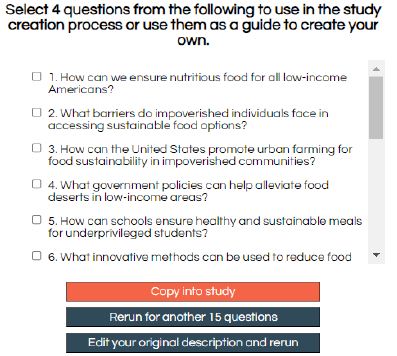

It is important to note that Table 1 can be replicated as many time as the researcher wishes. The questions end up allowing the researcher to look at different aspects of the problem. The results come out immediately to the researcher, as well as being stored in a file for subsequent AI ‘summarization’ described below. At the practical level, one can imagine a student interested in a topic looking at the questions for a topic again and again, as the student changes some of the text of the query (viz, the squib shown in Figure 2, Panel B). It is worth emphasizing that the Idea Coach works in real time, so that each set of 15 questions can be re-run and presented in the span of 5-15 seconds when the AI system is ‘up and running.’ Thus, the reality ends up being a self-educating system, at least one which provides the ‘picture of the topic’ through a set of related questions, 15 questions at a time. The actual benefit of this self-pacing learning by reading questioning is yet to be quantified in empirical measures, however (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Panel A shows the information about Idea Coach. Panel B shows the ‘box’ where the researcher creates the query for Idea Coach, in terms of ‘shaping’ the structure and information of the question.

Figure 3: The first six questions out of the 15 returned by Idea Coach to answer the request shown in Figure 2, Panel B. The remaining nine questions are accessed by scrolling through the screen.

It is relevant to note that AI-generated questions are beginning to be recognized as an aid to critical thinking, so that the Idea Coach strategy can be considered as part of the forefront of what might be the 21st century TACT program, Technical Aid to Creative thought (Oettinger, 1965, personal communication). Papers such as the new thesis by Danry [10] of MIT reflect this new thinking. Half-way around the world the same approaches are being pioneering in the Muslim world [11].

Once the questions are presented, it is left to the researcher to move on to completing the set-up of the Mind Genomics study, or to further request additional sets of 15 questions. When the creation of questions is complete, the researcher is instructed to provide four answer for each question. A separate paper will deal with the nature of ‘answers’ to the questions. This paper deals only with the additional analysis of the questions generated by Idea Coach.

AI Summarization and Extensions of Sets of 15 Questions

The second part of Idea Coach occurs after the researcher has competed the selection of the four questions, as well as completing the generation or selection of the four answers for each question. This paper does not deal with the creation of answers, but the process is quite similar to the creation of questions. The researcher creates the set of four questions, perhaps even editing/polishing the questions to ensure proper understanding, and tone. Once the questions are published, the Idea Coach generates four answer to each question. The entire process of summarization, for all of the set of 15 questions, takes about 15-30 minutes. The Excel file containing the ‘Answer Book’ with all summarizations is generally available 20 minutes after the questions and answers have been selected. The Answer book is available for download at the website (www.BimiLeap.com) and is emailed to the researcher as well.

We now go into each part of the summarization. The actual summarization for each set of 15 questions is presented on one tab of the Idea Book. We have broken up the summarizations into each major section, and then present the summarization by AI for the USA, followed by for Ghana, and finally for Egypt In this way the reader can see how the initial squib, the prompt to Idea Coach, differing only in the country, ends up with radically different ideas.

Key Ideas

The output from the first prompt had produced full questions. The ‘Key Ideas’ prompt strips the question format away, to show the idea or issue underlying the question. In this way, the ‘Key Ideas prompt can be considered simply as a change in format, with no new ideas emerging. Table 2 shows these ideas. It is not clear which is better to use. To the authors, it seems to be more engaging to present the ideas in the form of a question. When presenting the same material as ideas seems to be more sterile, less engaging, and without grounding.

Table 2: Key Ideas underlying the 15 questions

The use both of questions and of the ideas on which these questions are based have been addressed as part of an overall study of the best ways to learn. In the authors’ own words ‘Likewise, being constructive is better than being active because being constructive means that a learner is creating new inferences and new connections that go beyond the information that is presented, whereas being active means only that old knowledge is retrieved and activated.’ [12]

Before moving on to the next section, one may rightfully ask whether a student really learns by being given questions which emerge from a topic, or whether it is simply better to let the student flounder around, come up with questions, and hopefully discover other questions, either by accident, or by listening to the other students answer the same question and gleaning from those other answers new points of view [13]. The point of view taken here is that these aids to creative thought do not provide answers to questions, but rather open up the vistas, so that the questioner, research or student, can think is new but related directions. The output are additional, newly focused questions, rather than answers which put the question to rest. Quite the opposite [14]. The question opens up to reveal many more dimensions perhaps unknown to the researcher of the student when the project was first begun. In other words, perhaps the newly surfaced questions provide more of an education than one might have imagined.

Themes

With themes Idea Coach moves toward deconstructing the ideas, to identify underlying commonalities of issues, and the specific language in the questions supporting those commonalities. With ‘Themes’ the AI begins the effort to teach in a holistic manner, moving away simply from questions to themes which weave through the questions. For the current version of Idea Coach, the effort to uncover themes is done separately for each set of 15 questions, in order to make the task manageable. In that way the researcher or the student can quickly compare the themes generated from questions invoking the United States versus questions invoking Ghana, or questions invoking Egypt. Table 3 gives a sense of how the pattern of themes differ [15]. It is also important that the organization shown in Table 3, is the one provided by the Idea Coach AI, and not suggested by the researcher. Note that for Egypt, as contrasted with the USA and Ghana, Idea Coach refrained from grouping ideas into themes, but treated each idea as its own theme.

Table 3: Themes emerging from the collection of 15 questions for each country

Perspectives, an Elaboration of Themes

Perspectives advances the section of themes, which had appeared in Table 4. Perspectives takes the themes, and puts judgment around these themes, in terms of positive aspects, negative aspects, and interesting aspects. Perspectives are thus elaborations of themes. In other words, perspectives ends up being an elaboration of themes, useful as a way to cement the themes into one’s understanding.

Table 4: Perspectives (an elaboration of Themes)

What is Missing

As the analysis moves away from the clarification of the topic, it moves towards more creative thought. The first step is to find out what is missing, or as stated by Idea Coach, ‘Some missing aspects that can complete the understanding of the topic include: ’ It is at this point that AI moves from simple providing ideas to combining ideas, and suggesting ideas which may be missing.

It is at this stage, and as the stage of ‘innovation’ that AI reaches a new level. Rather than summarizing what has been asked, AI now searches for possible ‘holes’ and a path towards greater completeness in thinking. Perhaps it is at this level of suggesting missing ideas that the user begins to move into a more creative mode, although with AI suggesting what is missing one cannot be clear whether it is the person who is also thinking in these new directions, or whether the person is simply moving with the AI, taking in the information, and enhancing their thinking (Table 5).

Table 5: What is missing

Alternative Viewpoints

Alternative viewpoints involve arguing for the opposite of the question. We are not accustomed to thinking about counterarguments in the world of the everyday. Of course, we recognize counterarguments such as what occurs when people disagree. Usually, however, the disagreement is about something that people think to be very important, such as the origin of climate change or the nature of what climate change is likely to do. In such cases we routinely accept alternative viewpoints.

The Idea Coach takes alternative viewpoints and counterarguments to a deeper stage, doing so for the various issues which emerge from the questions. The embedded AI takes an issue apart and looks for the counterargument. The counterargument is not put forward as fact, but simply as a possible point of view that can be subject to empirical investigation for proof or disproof (Tables 6-9).

Table 6: Alternative viewpoint, showing negative arguments countering each point uncovered previously by Idea Coach using AI.

Table 7: Interested audiences.

The next AI analysis deals with the interested audiences for each topic. Rather than just listing the audience for each topic, the Idea Coach goes into the reasons why the audience would be interested, once again providing a deeper analysis into the topic, along with a sense of the stakeholders, their positions, their areas of agreement and disagreement.

Table 8: Opposing audiences.

Once again, in the effort to promote critical thinking, the Idea Coach provides a list of groups who would oppose the topic, and for each group explain the rationale for their opposition.

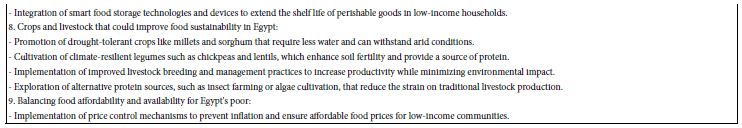

Table 9: Innovations.

The final table selected for the Idea Coach summarization is innovations, shown in Table 9. The table suggests new ideas emerging from the consideration of the questions and the previous summarizations. Once again the ideas are maintained with the constraints of the topic and reflect a disciplined approach to new ideas.

Discussion and Conclusions

The goal of the paper has been to show what is currently available to students and researchers alike. The objective of the demonstration has been to take a simple problem, one that might be part of everyday discourse, and use that problem to create a ‘book of knowledge’ from the topic, using questions and AI elaboration of the questions.

We hear again and again about the importance of critical thinking, but we are not given specific tools to enhance critical thinking. As noted in the introduction, in the 1960’s, the late professor Anthony Gervin Oettinger of Harvard University began his work on creative thought. We might not think that programming a computer to go shopping is an example of creative thought, but in the 1960’s it was (Oettinger, xxx). Now, just about six decades later, we have the opportunity to employ a computer and AI create books that help us thinking critically about a problem. We are not talking here about giving factual answers, actual ‘stuff,’ but really coaching us how to think and how to think comprehensively about the ideas within a societal milieu, a milieu of competing ideas, of proponents and opposers who may eventually agree on solutions that address or resolve issues as thorny as food sustainability. If sixty years ago teaching a computer (the EDSAC) to go shopping was considered a TACT, a technical aid to creative thought, perhaps now co-creating a book of pointed inquiry about a topic might be considered a contribution of the same type, albeit one more attuned to today. The irony is that sixty years ago the focus was on a human programming a machine ‘to think,’ whereas today it is the case of a machine coaching a human how to think. And, of course, in keeping with the aim of this new to the world journal, the coach is relevant to thinking about any of the topics germane to the journal. This same paper could be created in an hour for any topic.

References

- Cojocariu VM, Butnaru CE (2014) Asking questions–Critical thinking tools. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 128: 22-28.

- Lai ER 2011. Critical thinking: A literature review. Pearson’s Research Reports 6: 40-41.

- Miller SA& Forrest JL (2001) Enhancing your practice through evidence-based decision making: PICO, learning how to ask good questions. Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice 1: 136-141.

- Nicholar J, Hughes C & Cappa C (2010) Conceptualising, developing and accessing critical thinking in law. Teaching in Higher Education 15: 285-297.

- ŽivkoviĿ S 2016. A model of critical thinking as an important attribute for success in the 21st century. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 232: 102-108.

- Bossert WH, Oettinger AG 1973. The Integration of Course Content, Technology and Institutional Setting. A Three-Year Report, 31 May 1973. Project TACT, Technological Aids to Creative Thought.

- Moskowitz H, Kover A & Papajorgji P (eds), (2022) Applying Mind Genomics to Social Sciences. IGI Global.

- United Nations, Undated. “Global Issues,” accessed January 27, 2024.

- Rothe A, Lake BM & Gureckis TM 2018. Do people ask good questions? Computational Brain & Behavior 1: 69-89.

- Danry VM (2023) AI Enhanced Reasoning: Augmenting Human Critical Thinking with AI Systems (Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

- Fariqh N 2023, October. Developing Literacy and Critical Thinking with AI: What Students Say. In .Proceedings Annual International Conference on Islamic Education (AICIED) 1: 16-25.

- Chi MTH 2009. Active-Constructive-Interactive: A Conceptual Framework for Differentiating Learning Activities. Topics in Cognitive Science 1: 73-105. [crossref]

- Moskowitz HR, Wren J & Papajorgji P 2020. Mind Genomics and the Law. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

- Niklova, N (2021) The art of asking questions: Flipping perspective. In: EDULEARN21 Proceedings Publication 2816-2825.

- Oettinger AG. Machine translation at Harvard 2003. In: Early Years in Machine Translation, Memoirs and Biographies of Pioneers, (ed. W.J. Hutchins), John Benjamin’s Publishing Company, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, pp. 73-86.