Abstract

Background: Sadomasochistic fantasies are often stigmatized and not easily disclosed to friends and family members. Although the nature of these fantasies is still incompletely understood, more frequent unconventional sexual fantasies seem to be associated with male gender with non-heteronormative sexual orientation and with higher educational level.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional study in which subjects provided information through a self-reported questionnaire in a face-to-face interview. This tool included questions assessing sociodemographic characteristics, the Beck Depression Inventory, and the subscale “sadomasochistic fantasies” of the Wilson Sexual Fantasy Questionnaire. A total of 412 medical students aged 18 and over attending first through sixth year at a medical school were randomly selected and recruited to participate.

Results: Non-heteronormativity and illicit drug use were directly and positively correlated with higher scores on sadomasochistic sexual fantasies. In addition, non-heteronormativity was a mediator variable in the model between being male and having higher scores on sadomasochistic sexual fantasies.

Conclusion: It is possible that unconventional sexual fantasies are more frequent in certain social groups, such as non-heteronormative males with high educational level. Although the use of psychoactive substances was correlated with sadomasochistic sexual fantasies, there are scarce scientific data to support this finding.

Keywords: Sadomasochistic fantasies, University Students,Heteronormativity

Introduction

The deliberate act of mentally envisioning a sexual scenario involving a target and/or behavior is a normal part of human sexuality. The content of the mental imagery or sexual fantasy frequently reflects one’s sexual interest and is experienced as sexually arousing [1]. In fact, some studies have shown a positive correlation between the experience of arousing sexual fantasies and sexual satisfaction [2].

There are important reasons for studying the diversity of sexual fantasies. First, although sexual fantasies are universally experienced, they can affect sexual behavior; second, sexual fantasies can be influenced by what people have previously seen, read, or done; third, repetitive sexual fantasies can help to shape our sexual schema or script; fourth, as sexual fantasies are private, they may be more revealing than actual behavior [1]. In sum, sexual fantasies can reflect our sexual behavior, which in turn can reflect them.

Of the enormous variety of sexual fantasies, sadomasochistic fantasies are often stigmatized and not easily disclosed to friends and family members by the fantasizers [3,4]. In addition, individuals with ingrained sadomasochistic sexual fantasies might need to reshape their identity to cope with shame, guilt, self-labeling, and self-hatred, and might need to overcome phases of dissatisfaction and depression before assuming or even expressing these sexual fantasies [5].

In fact, sadism and masochism have also been stigmatized medically. It was only in the 1970s and 1980s that a growing body of studies from the social sciences took a non-pathological view of sadomasochistic fantasies, practices, and behaviors [6]. Studies of consensual sadomasochistic practices have shown the healthy aspects of this behavior, such as improvement of intimacy between practitioners and greater creative stimulation [7]. In addition, associations of sadomasochistic practices with mental instability, depression, anxiety, and antisocial or psychotic traits have not been supported [8, 9]. Thus, since the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [10] the terms sexual sadism and sexual masochism were changed to sexual sadism disorder and sexual masochism disorder in order to draw a line between non-pathological and pathological sexual behavior. In truth, one of the most important distinctions between deviant and normal sadomasochistic behavior is the presence or lack of consent. This perspective is also assumed within sadomasochistic communities, where consensual play and sex are unbreakable principles [11]. Despite this, the nature of sadomasochism is still incompletely understood, even though many studies have applied a broad variety of qualitative and quantitative methods [12].

Despite the demedicalization of consensual sadomasochistic behaviors, we should nonetheless consider that certain psychosocial factors seem to be linked to a higher diversity of sexual fantasies and practices in general. Higher diversity of sexual practices is consistently found to be associated with male gender, non-heteronormative sexual orientation, and higher educational level [13-16]. Considering these findings, nonclinical clusters of people with more intense unconventional sexual fantasies could be grouped into certain socio-demographic profiles [17]. In a somewhat different way, some studies have suggested that, although men show more frequent sadomasochistic fantasies, there are a large number of women in sadomasochistic communities [18-20]. In addition, [21] contends that “those who are most attracted to masochism may be the women (…). The women turn to masochism to live out the humiliation, the submission that they no longer have to endure anywhere else, or to remind themselves of other realities.” Based on these contrasting assumptions, it is possible that there is a mediator variable between biological sex and sadomasochistic sexual fantasies.

Still considering differences between sadomasochistic fantasizers and non-fantasizers, drug use has been scarcely investigated. It is important to note that it is possible that some sexual fantasies or feelings may be related to urges or cravings for drugs. Many drug users become trapped in a “reciprocal relapse” pattern in which a sexual behavior precipitates relapse to drugs and vice-versa [22]. According to some sadomasochistic communities, “just as in the greater population, there are many people in these communities who identify as clean and sober, and there are many who do not” [23]. This statement demonstrates the heterogeneity of those that have sadomasochistic sexual fantasies in terms of drug use. Examining such heterogeneity, a study with 164 sadomasochistically oriented males showed that the use of psychoactive substances before or during sadomasochistic sessions is not negligible. About 26%, 17%, and 5% of the participants of this sample admitted to using alcohol, poppers, and marijuana, respectively [24]. It is important to note here that poppers (volatile nitrites) are forbidden for recreational use in Brazil by the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (volatile nitrites are approved for use only for industrial purposes).

Also in line with other studies linking psychological problems with unconventional sexual fantasies, an association of traumatic childhood with sadomasochism and intermittent depression has been suggested [25]. In truth, depression symptoms can consist of a phase that individuals with sadomasochistic fantasies have to overcome before accepting and expressing them. Although these mental problems, drug use and depressive symptoms, may be directly or indirectly associated with unconventional sexual fantasies and behaviors, there does not seem to be any causal nexus. That said, we understand that sexual science would benefit from more systematic assessments of sadomasochistic fantasies and behaviors in clinical and nonclinical samples.

This study aimed to investigate whether psychosocial aspects, such as male gender and non-heteronormative sexual orientation, are associated with more frequent sadomasochistic sexual fantasies. In addition, we evaluated whether drug use and depressive symptoms are correlated with these sexual fantasies in a nonclinical sample of university students.

Method

Procedure

Permission to use the Wilson Sexual Fantasy Questionnaire (WSFQ) was obtained from the instrument’s marketers (CymeonTM Research, Sydney, Australia). Prof. Glenn Wilson was also contacted by our staff, and he referred us to the CymeonTM Research team. The original version was translated using the standard processes of back translation [26]. The English version of the instrument was translated into Portuguese by a team including one professor, four psychiatrists, and two psychologists with experience in sexual disorders and competency in both English and Portuguese languages, and two independent bilingual native speakers. The staff worked collaboratively to ensure that the instrument had semantic equivalence across the languages and conceptual equivalence across cultures. The translation coordinator compared both versions and reconciled any differences. Finally, the team compiled the Portuguese version and chose the most appropriate wording for clarity and similarity to the original. The final Portuguese version was formalized after the team discussed culturally problematic issues.

The Portuguese version was then independently translated back to English by two separate translators, neither of whom had previously seen the original scale. The back-translated versions were also evaluated and discussed by the team. A pilot study was then performed on a small sample (N = 10) of healthy individuals from diverse educational levels to examine whether any items on the WSFQ were perceived as difficult. No problematic items requiring revision were found.

Subsequently, a cross-sectional study was conducted to investigate associations or correlations between some psychosocial variables, mainly among those potentially related to unconventional sexual fantasies, such as biological sex, sexual orientation, illicit drug use, and depression. The investigators were specially trained medical graduate and postgraduate students. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of ABC Medical School, Santo André, São Paulo, Brazil.

Participants

Between November 2016 and August 2019, a total of 412 medical students aged 18 and over attending the first through sixth year at one medical school were randomly selected and recruited to participate in this study. They were assured that their participation was voluntary, that only the researchers would see the data, and that all data would be kept confidential. A financial reward was not provided because this is not allowed under Brazilian law.

Important participant outcomes were compared based on 11 variables: biological sex, age, race or ethnicity, marital status, lifetime alcohol use, lifetime illicit drug use (marijuana, poppers, and cocaine were grouped into just one group), family members with alcohol use problems, family members with illicit drug use problems, sexual orientation, scores on depression symptoms, and scores on sadomasochistic sexual fantasies. Sex was coded as male, female, and intersex. Monthly income was not coded because our participants follow a full-time course of study.

Measures

This was a cross-sectional study in which subjects provided information through a self-reported questionnaire. This tool included questions assessing sociodemographic characteristics and the following inventories: The Beck Depression Inventory and the subscale “sadomasochistic fantasies” of the Wilson Sexual Fantasy Questionnaire.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

This inventory measures behavioral responses related to depression among adults and adolescents. In this 21-item instrument, scores above 10 (score range: 0–63) indicate the presence of a depressive syndrome [27, 28]. A sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 0.83 are obtained with a cut-off score of 9/10.

The Wilson Sex Fantasy Questionnaire (WSFQ)

This questionnaire is a 40-item self-report measure of sexual fantasies comprising a range of sexual themes “from the normal to the deviant and potentially harmful” [29]. Each item is scored on a four-point scale ranging from Never (0) to Often (3) across five different contexts (e.g., Daytime fantasies, Fantasies during intercourse or masturbation, Dream while asleep, Have done in reality, and Would do in reality). When assessing the frequency of sexual fantasy use, it is considered advisable only to use responses for Daytime fantasies, since scores for the other four contexts are highly correlated with Daytime dreams [30, 31]. Four subscales are derived from this instrument, including intimate (e.g., kissing passionately, having intercourse with a loved partner, being masturbated to orgasm by a partner), impersonal (e.g., sex with strangers, watching others having sex, fetishism), exploratory (e.g., group sex, promiscuity, mate-swapping), and sadomasochistic sexual fantasies (e.g., whipping or spanking, being forced to have sex). Each subscale has 10 items and this 4-factors structure has demonstrated consistency across multiple assessments [32, 33]. In line with the aims of this study, we only used the sadomasochistic sexual fantasy subscale. The following question was constructed for the participants: How often do you fantasize about the theme below at various times?

Analysis

Univariate analyses were used to compare the sociodemographic and psychometric features between men and women and between heteronormative and non-heteronormative participants. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests, following the Monte Carlo method. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test.

In order to develop a correlational model, we performed a Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). Maximum likelihood estimation was used to estimate the fit of the model. TheComparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted GFI (AGFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) were used to evaluate model fit. Some standard recommendations regarding values for global model fit were followed. Specifically, CFI, TLI, GFI, and AGFI values greater than 0.90 and RMSEA and SRMR values lower than 0.08 were deemed indicative of acceptable model fit [34, 35]. As the chi-square value is dependent on the sample size, we calculated the ratio of chi-square to the degrees of freedom (c2/df), where a value of 2 or lower is an acceptable c2/df ratio [36].

Results

Of the questionnaires applied, 8 (1.94%) were discarded due to incomplete answers, leaving 402 participants. Of the participants, 200 (49.75%) were male and the mean age of the total sample was 21.45 (SD = 2.35) years old. Our sample had neither intersex nor transgender participants.

Descriptive analysis

As it is shown in Table 1, when biological male and female respondents were compared, male students showed more frequent non-heteronormative sexual orientation, and female students demonstrated higher mean scores on the BDI. There were no significant differences between the sexes in age, marital status, alcohol and illicit drug use, family members with alcohol and drug use problems, or mean scores on sadomasochistic sexual fantasies. As shown in Table 2, when heteronormative and non-heteronormative students were compared, those that admitted to non-heteronormativity demonstrated higher scores on the BDI and on sadomasochistic sexual fantasies, and more frequent family members with alcohol use problems. There were no statistically significant differences regarding the other psychosocial variables.

Table 1. Psychosocial and Psychometric features between male and female Medical University students.

|

Variables |

Male |

Female |

Test |

p |

|

Age, mean (SD) |

21.56 (2.54) |

21.34 (2.16) |

t = 0.90, 402df |

0.90 |

|

Race, n (%) |

173 (86.50) |

165 (80.88) |

χ2 = 2.33, 1df |

0.13 |

|

Marital status, n (%) |

198 (99) |

200 (98.04) |

χ2 = 0.64, 1df |

0.43 |

|

Alcohol use, n (%) |

163 (81.50) |

176 (86.27) |

χ2 = 1.71, 1df |

0.19 |

|

Illicit drug use, n(%) |

60 (30) |

54 (26.47) |

χ2 =0.62, 1df |

0.43 |

|

Family members with alcohol use problems, n (%) |

61 (30.50) |

53 (25.98) |

χ2 = 1.02, 1df |

0.31 |

|

Family members with illicit drug use problems, n (%) |

34 (17) |

32 (15.69) |

χ2 = 1.28, 1df |

0.72 |

|

Sexual orientation, n (%) |

180 (90) |

195 (95.59) |

χ2 = 4.73, 1df |

0.03* |

|

BDI, mean (SD) |

5.78 (4.97) |

8.36 (6.43) |

t = -4.50, 402df |

< 0.01** |

|

Sadomasochistic fantasies, mean (SD) |

4.01(4.01) |

4.43 (3.36) |

t = -1.13, 402df |

0.26 |

Note: * p < 0.04; ** p < 0.01; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory

Table 2. Psychosocial and Psychometric features between Medical University students in accordance with the sexual orientation.

|

Variables |

Heteronormative |

Non-Heteronormative |

Test |

p |

|

Age, mean (SD) |

21.46 (2.38) |

21.35 (1.97) |

t = 0.25, 402df |

0.81 |

|

Race, n (%) |

314(83.73) |

24 (68.96) |

χ2 = 0.19, 1df |

0.80 |

|

Marital status, n (%) |

369 (98.40) |

29 (100) |

χ2 = 0.47, 1df |

>0.99 |

|

Alcohol use, n (%) |

314 (83.73) |

25 (86.21) |

χ2 = 0.12, 1df |

0.73 |

|

Illicit drug use, n(%) |

104 (27.33) |

10 (34.48) |

χ2 =0.61, 1df |

0.44 |

|

Family members with alcohol use problems, n (%) |

99 (26.40) |

15 (51.72) |

χ2 = 8.52, 1df |

<0.01** |

|

Family members with illicit drug use problems, n (%) |

59 (15.73) |

07 (24.14) |

χ2 = 1.39, 1df |

0.24 |

|

BDI, mean (SD) |

6.89 (5.94) |

9.59 (4.66) |

t = -2.39, 402df |

0.02* |

|

Sadomasochistic fantasies, mean (SD) |

4.11(3.58) |

5.62 (4.81) |

t = -2.13, 402df |

0.03* |

Note: * p < 0.04; ** p < 0.01; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory

SEM analysis

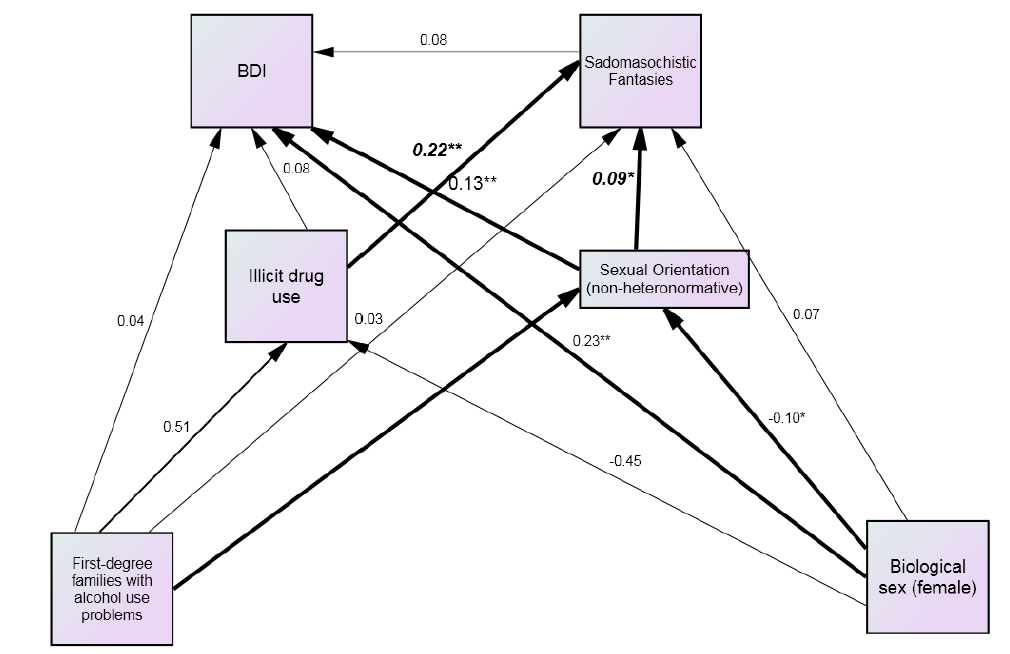

For the purposes of our SEM analysis, items were loaded uniquely on their respective factors and the factor loadings were fixed at 1.0. The sample was then evaluated using bootstrapping (800 bootstrap samples) with the Bollen-Stine Bootstrap statistic being calculated to verify absolute fit. As shown in Figure 1, the model fitted the data well, with c2/df= 0.69; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.99; GFI = 0.99; AGFI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.012 [95% CI = 0.010-0.191]; SRMR = 0.02; and a Bollen-Stine statistic of p = 0.51.

Figure 1. Psychosocial and psychometric features correlated with sadomasochistic fantasies.

This model showed that non-heteronormativity and illicit drug use were directly and positively correlated with higher scores on sadomasochistic sexual fantasies. In addition, this model showed that non-heteronormativity was a mediator variable between having family members with alcohol problems and higher scores on sadomasochistic sexual fantasies. Furthermore, the variables of female sex and non-heteronormativity were directly and positively correlated with higher scores on depression. Non-heteronormativity also mediated the correlation between female sex and higher scores on depression.

Discussion

This study supports previous ones that have shown no correlation between depression symptoms and sadomasochistic fantasies, and that non-heteronormative persons have a higher frequency of these sexual fantasies. In addition, it found a correlation between illicit drug use and sadomasochistic fantasies.

Being male was not correlated with more frequent sadomasochistic sexual fantasies; however, being male was correlated with non-heteronormativity, which in turn was correlated with these unconventional sexual fantasies. We should consider that non-heteronormativity was a mediator variable between being male and having more frequent sadomasochistic fantasies in the correlational model. That said, it is possible that unconventional sexual fantasies are more frequent in certain social groups, such as non-heteronormative males with high educational level.

With regard to drug use, there is scarce evidence of an association with unconventional sexual fantasies. A few studies have investigated this use among sadomasochistically oriented people [24] and therefore it is necessary to devote greater attention to this theme, since our study shows a positive and direct correlation. It is possible that users of a variety of psychoactive substances experience strong aphrodisiac effects and disinhibition. This combination may result in obsessive pornography viewing, diverse sexual fantasies (including unconventional ones), and unsafe sexual practices [37]. Nonetheless, there is no definitive link between “kinky” sex and drug use to date.

Although comparisons between male and female and between heteronormative and non-heteronormative students in terms of depression symptoms were not the main goal of this study, the higher mean scores on depression in females than in males, mainly among young people [38-40] and in non-heteronormative persons [41-43] are widely supported in the scientific literature. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that sexual minorities show a higher risk of having a family history of alcohol use problems than heterosexuals [44, 45]. Although the interpretation of this last association is politically sensitive [46] the fact is that this study does not show a causal relationship between sexual orientation and parental problems. It is possible to say here that non-heteronormative students may show higher self-reflection during the coming-out process or have a desire to endorse their own sexual orientation, leading them to reveal this fact more emphatically [47].

Although some authors have found significant associations between non-heteronormativity and alcohol and/or illicit drug use [48, 49] our study was not able to show this type of association. It is possible that given the notable and welcome reduction of the stigma, shame, and secrecy surrounding non-heteronormativity, the differences in the incidence of alcohol and drug use may be diminishing between heterosexuals and homosexuals/bisexuals. Also, the social context where people live can have a notable influence on the differences between heteronormative and non-heteronormative persons regarding alcohol and drug use [50] and this sample consisted of university students at a private institution.

In addition, the correlation between being male and non-heteronormative is not surprising. In Brazil, like in other diverse countries, the prevalence of homosexuals and bisexuals is higher in men, that is, almost 6% of males identify as gay and 2% identify as bisexual, while almost 3% of women identify as lesbian and 1% as bisexual [51].

This study showed that sadomasochistic fantasies in this sample of university students are more frequent in a group characterized by a non-heteronormative sexual orientation and reporting drug use. Although the first assertion has empirical support, the drug use among fantasizers needs further investigation.

There are several limitations in this study that need to be pointed out:

a) Response accuracy of research using self-response questionnaires may be less than fully satisfactory;

b) The university population is unrepresentative of the general population; and

c) The study’s cross-sectional design precludes drawing causal inferences and only provides information about population frequency and characteristics in a “snapshot” at a specific time.

References

- Leitenberg H, Henning K(1995) Sexual fantasy. Psychological Bulletim117: 469-496.

- Colon Vilar G, Concepcion E, Galynker I, Tanis T, Ardalan F, et al.(2016) Assessment of sexual fantasies in psychiatric inpatients with mood and psychotic disorders and comorbid personality disorder traits. The Journal of Sex Medicine 13:262-269.[Crossref]

- Bezreh T, Weinberg TS, Edgar T (2012) BDSM disclosure and stigma management: Identifying opportunities for sex education. American Journal of Sexuality Education7: 37-61.[Crossref]

- Wright, S. (2006). Discrimination of SM-identified individuals. Journal of Homosexuality, 50, 217-231.

- Kamel GWL (1983) The leather career: On becoming a sadomasochist. In T. K. Weinberg (Ed.), S and M: Studies in sadomasochism. Buffalo: Prometheus Books.

- Weinberg TS (2006) Sadomasochism and the social sciences: A review of the sociological and social psychological literature. Journal of Homosexuality 50: 17-40.[Crossref]

- Williams DJ (2009) Deviant leisure: Rethinking “the good, the bad, and the ugly”. Leisure Science31: 207-213.

- Connoly PH (2006) Psychological functioning of Bondage Domination Sado-Masochism (BDSM) practitioners. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexualitys 18: 79-120.

- Cross PA, Matheson K (2006) Understanding sadomasochism: An empirical examination of four perspectives. Journal of Homosexuality, 50: 133-166.[Crossref]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013)Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th edn.). Washington: Author.

- Sagarin BJ, Cutler B, Cutler N, Lawler-Sagarin KA, Matuszewich L (2009) Hormonal changes and couple bonding in consensual sadomasochistic activity. Archives of Sexual Behavior38: 186-200.[Crossref]

- Weierstall R, Giebel G (2017) The sadomasochism checklist: A tool for the assessment of sadomasochistic behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46: 735-745.[Crossref]

- Bhugra DRB, Rahul B (2006) Sexual fantasy in gay men in India: A comparison with heterosexual men. Sexual and Relationship Therapy21: 197-207.

- Gagnon JH, Simon W (1987) The sexual scripting of oral genital contacts. Archives of Sexual Behavior16: 1-25.[Crossref]

- Moser C, LevittEE (1987) An exploratory-descriptive study of a sadomasochistically oriented sample. The Journal of Sex Research23: 322-337.

- Nordling N, Sandnabba NK, Santtila P, Alison L (2006) Differences and similarities between gay and straight individuals involved in the sadomasochistic subculture. Journal of Homosexuality50: 41-57.[Crossref]

- Joyal CC (2015) Defining “normophilic” and “paraphilic” sexual fantasies in a population-based sample: On the importance of considering subgroups. Sexual Medicine3: 321-330.[Crossref]

- Breslow N, Evans L, Langley J (1985) On the prevalence and roles of females in the sadomasochistic subculture: Report of an empirical study. Archives of Sexual Behavior 14: 303-317. [Crossref]

- Holvoet L, Huys W, Coppens V, Seeuws J, Goethals K, e (2017) Fifty shades of Belgian gray: The prevalence of BDSM-related fantasies and activities in the general population. The Journal of Sex Medicine14: 1152-1159.[Crossref]

- Rehor JE (2015) Sensual, erotic, and sexual behaviors of women from the “kink” community. Archives of Sexual Behavior44: 825-836.[Crossref]

- Phillips A (1998)A Defence of Masochism. London: Faber and Faber Ltda.

- Washton AM, Stone-Washton N (1993) Outpatient treatment of cocaine and crack addiction: A clinical perspective. Washington: National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

- Ortmann DM, Sprott RA (2013)Sexual outsiders: Understanding BDSM sexualities and communities.Toronto: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Sandnabba NK, Santilla P, Nordling N (1999) Sexual behavior and social adaptation among sadomasochistically-oriented males. Journal of Sex Research36: 273-282.

- Gabriel JBS (2007) Early trauma in the development of masochism and depression. International Forum of Psychoanalysis 6: 231-236.

- Guillemin F, BombardierC, Beaton D (1993) Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: Literature review and proposed guidelines. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology46: 1417-1432.[Crossref]

- Beck AT, Rial WY, Rickels K (1974) Short form of depression inventory: Cross-validation. Psychological Reports 34: 1184-1186. [Crossref]

- Furlanetto LM, Mendlowicz MV, Romildo Bueno J (2005) The validity of the Beck Depression Inventory-Short Form as a screening and diagnostic instrument for moderate and severe depression in medical inpatients. Journal of Affective Disorder86: 87-91. [Crossre]

- Wilson G (1988) Measurement of sex fantasy. Sex and Marital Therapy3: 45-55.

- Bartels RM, Lehmann RJB, Thornton D (2019) Validating the utility of the Wilson Sex Fantasy Questionnaire with men who have sexually offended against children. Frontiers in Psychiatry10: 206. [Crossref]

- Wilson G (1978)The Secrets of Sexual Fantasy.Toronto: JM Dent & Sons Ltda.

- Plaud JJ, Bigwood SJ (1997) A multivariate analysis of the sexual fantasy themes of college men. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy23: 221-230.[Crossref]

- Sierra JC, Ortega V, Zubeidat I (2006) Confirmatory factor analysis of a Spanish version of the sex fantasy questionnaire: Assessing gender differences. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy32: 137-159.

- Gilson KM, Bryant C, Bei B, Komiti A, Jackson H, et al., (2013) Validation of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ) in older adults. Addictive Behaviors38: 2196-2202.[Crossref]

- Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling6: 1-55.

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2007)Using Multivariate Statistics.Boston: Pearson Education.

- Slavin MN, Kraus SW, Ecker A, Sartor C, Blycker GR, et al., (2017) Marijuana use, marijuana expectancies, and hypersexuality among college students. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity24: 248-256.[Crossref]

- lbert PR (2015) Why is depression more prevalent in women? [Editorial]. Journal of Psychiatry Neurosciences40:219-221.[Crossref]

- Cyranowski JM, Frank E, Young E, Shear MK (2000) Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression: A theoretical model. Archives of General Psychiatry57: 21-27. [Crossref]

- Ford DE, Erlinger TP (2004)Depression and C-reactive protein in US adults: Data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Archives of Internal Medicine164: 1010-1014.[Crossref]

- King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, et al., (2008) A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry8: 70.[Crossref]

- Lee C, Oliffe JL, Kelly MT, Ferlatte O (2017) Depression and suicidality in gay men: Implications for health care providers. American Journal of Men`s Health11: 910-919.[Crossref]

- Pompili M, Lester D, Forte A, Seretti ME, Erbuto D, et al., (2014) Bisexuality and suicide: A systematic review of the current literature. The Journal of Sexual Medicine11: 1903-1913.[Crossref]

- McCabe SE, West BT, Hughes TL, Boyd CJ (2013) Sexual orientation and substance abuse treatment utilization in the United States: Results from a national survey. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment44: 4-12.[Crossref]

- McCabe SE, West BT, Hughes TL, Boyd CJ (2013) Sexual orientation and substance abuse treatment utilization in the United States: Results from a national survey. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment44: 4-12.[Crossref]

- Roberts AL, Glymour MM, Koenen KC (2013) Does maltreatment in childhood affect sexual orientation in adulthood? Archives of Sexual Behavior42: 161-171.[Crossref]

- Corliss HL, Cochran SD, Mays VM (2002) Reports of parental maltreatment during childhood in a United States population-based survey of homosexual, bisexual, and heterosexual adults. Child Abuse & Neglect 26: 1165-1178.[Crossref]

- Green KE, Feinstein BA (2012) Substance use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: An update on empirical research and implications for treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors26:265-278.[Crossref]

- Hughes T, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, Boyd CJ (2010) Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction105: 2130-2140.[Crossref]

- Duncan DT, Hatzenbuehler ML, Johnson RM (2014) Neighborhood-level LGBT hate crimes and current illicit drug use among sexual minority youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence135: 65-70.[Crossref]

- Abdo C (2004)Estudo da vida sexual do brasileiro (Study on the Sexual Life of Brazilians) (1st edn.). São Paulo: Bregantini.