DOI: 10.31038/ALE.2024121

Abstract

This paper presents a new approach to understand FMI (foreign malign influences) such as disinformation and propaganda. The paper shows how to combine AI with the emerging science of Mind Genomics to put a “human face” on FMI, and through simulation suggest how to counter FMI efforts. The simulations comprise five phases. Phase 1 simulates a series of interviews from people about FMI and their suggestions about how to counter the effects of FMI. Phase 2 simulates questions and answers about FMI, as well as what to expect six months out, and FMI counterattacks. Phase 3 uses Mind Genomics thinking to suggest three mind-sets of people exposed to FMI. Phase 4 simulates being privy to a strategy meeting of the enemy. Phase 5 presents a simulation of a briefing document about FMI, based upon the synthesis of dozens of AI-generated questions and answers. The entire approach presented in the paper can be done in less than 24 hours, using the Mind Genomics platform, BimiLeap.com, with the embedded AI (ChatGPT 3.5) doing several levels of analysis, and with the output rewritten and summarized by AI (QuillBot). The result is a scalable, affordable system, which creates a database which can become part of the standard defense effort.

Keywords

AI simulations, Disinformation, Mind genomics, Foreign malign influences

Introduction: The Age of Information Meets the Agents of Malfeasance

Information warfare is a powerful tool for adversarial governments and non-state actors—with propaganda, fake news, and social media manipulation being key strategies to undermine democracies, particularly the United States. Foreign actors like Russia and China exploit socio-political divides to spread fake news, amplifying racial tensions and cultural clashes. The U.S. government is increasingly concerned about disinformation and propaganda efforts from foreign adversaries, with agencies like the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) warning about evolving tactics. The private sector, particularly social media companies, has a key role in countering propaganda but has been criticized for being insufficient. To combat these threats, the U.S. government, social media companies, and civil society organizations need to collaborate effectively, using innovative techniques to detect and counter malign influences without infringing on civil liberties [1-4].

The war on disinformation continues apace. Sustained efforts are evermore vital to preserve the integrity of democratic systems. Malign influences do their evil work through their deliberate use of deceptive or manipulative tactics. The actors may be state or non-state actors, who spread false information, distort public perception, or undermine trust in democratic institutions. Traditional media plays one of two roles, or sometimes both roles. Traditional media either amplifies misinformation by reporting unverified stories or counteracts it by adhering to journalistic standards of fact-checking and verification. The outcome is a tightrope, balancing act, one part being freedom of expression, the other being the structural harm from the willy-nilly acceptance of potentially injurious information. Balancing freedom of expression with the need to protect citizens from harmful deceit can be difficult [5-7].

Strategies currently in use include increased investment in fact- checking initiatives, creating algorithms to detect fake accounts and bots, public awareness campaigns about media literacy, and stricter regulations about political ad funding, respectively. Nonetheless, it is inevitable that challenges remain in detecting and removing disinformation, clearly in part due to the avalanche effect, the sheer volume of content and evolving tactics. Fact-checking can help reduce the spread of false stories, but it is often limited by reach, speed, and the willingness of individuals to believe corrections. Artificial intelligence may identify patterns in disinformation campaigns, flagging suspicious accounts or content, but may struggle to distinguish among opinion, satire, and deliberately harmful misinformation [2,8].

Misinformation can erode trust in traditional media by making it difficult for the public to discern what is true and what is propaganda. Broad laws targeting online speech often raise concerns about censorship and the infringement of free speech. Media literacy programs give people the tools to critically evaluate sources and identify fake news, but they require widespread implementation and can be hindered by existing biases [9-11].

This paper moves the investigation of malign influences such as fake news into the direction of the analysis of the everyday. The paper attempts to put a human face on malign influences by using AI to simulate interactions with people, with questions that people might ask, and with ways that people deal with information sent out by “actors” inimical to the United States. The paper presents AI “exercises” using the Mind Genomics platform, BimiLeap.com.

Phase 1: Putting a Human Face on the Topic Through Snippets of Stories with Recommendations

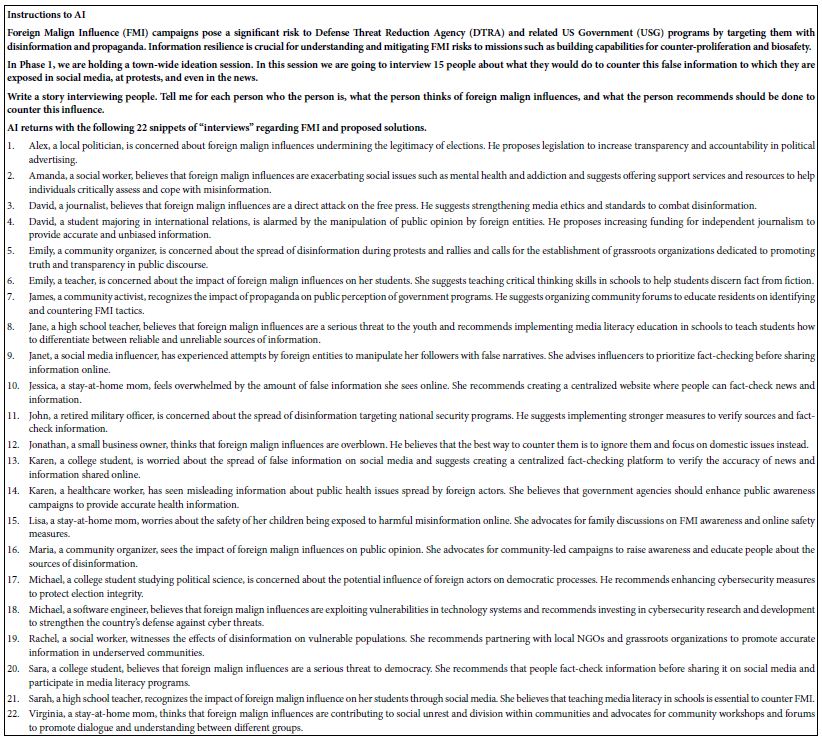

The psychological principle of presenting a “human face” to issues like foreign malign influences (FMI) resonates with people as they are naturally driven by stories. Simulating interviews with individuals recounting personal struggles with misinformation injects warmth, vulnerability, and relatability, making it easier to feel empathy [12-14]. Building trust and emotional connection is essential in addressing the erosion of trust in media, government, and social institutions. To this end, Table 1 presents 22 short, simulated interviews with ordinary people, as well as the recommendation that they make.

Table 1: AI simulated snippets of interviews and recommendations about FMI (foreign malign influences).

Phase 2: Simulating Advice

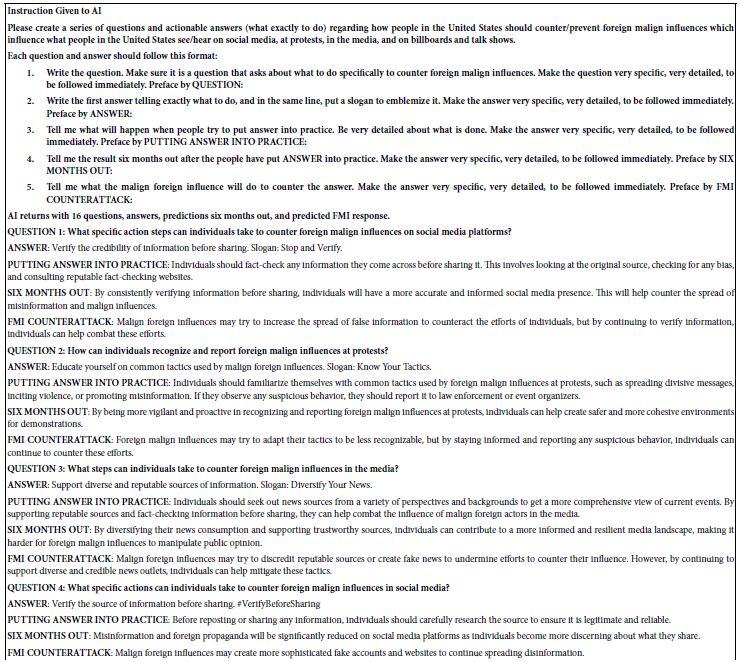

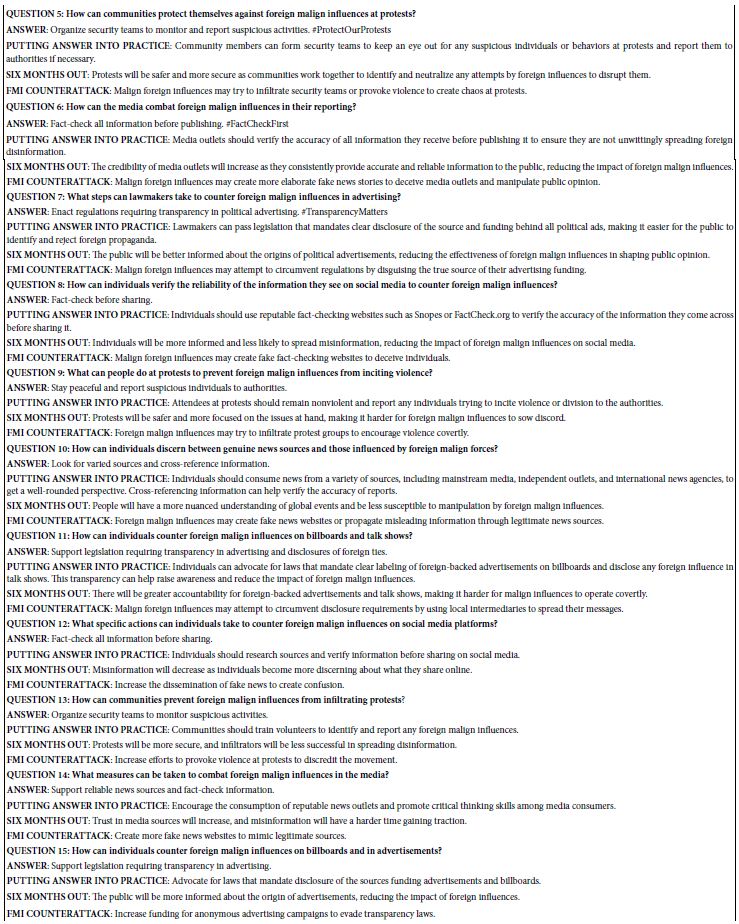

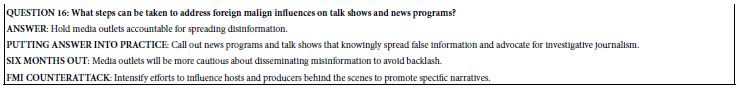

AI can be used to generate specific questions and detailed, actionable answers to counter foreign malign influences (FMI). This approach allows for quick identification of common points of intrusion or manipulation by foreign actors, providing an organized strategy to address key vulnerabilities. AI-driven directives prioritize immediate actions, enabling individuals or institutions to respond swiftly to rapid information warfare. AI’s ability to flesh out complex situations while accounting for multiple variables allows it to present tangible alternatives and outcomes with ease through simulation, providing a “what if ” perspective. This actionable level of detail bridges the gap between theory and practice, making recommendations feel natural and embedded in the broader scenario being played out in real-time simulation. The iterative nature of AI allows for constant feedback and improvement, making it better suited to the evolving circumstances of FMIs. AI’s role also provides clarity and simplicity, making it suitable to create directives for targeted messaging campaigns, media outlets, and the general public [15-17].

Table 2 shows questions and answers based on a simple AI “understanding” of the topic, along with additional analyses such as predictions of what might happen six months out, and FMI’s counterstrategy. Information presented in this manner may produce more compelling reading, and a greater likelihood that the issues of FMI end up recognized and then thwarted.

Table 2: Questions, answers, strategies and counterstrategies for FMI efforts.

Phase 3: Mind-sets of People in the United States Exposed to FMI

Mind-sets are stable ways individuals react to stimuli or situations which are shaped by cognitive processes, personal experiences, emotional predispositions, and sociocultural factors [18-21]. AI- generated mind-sets can be crucial for understanding how different people process misleading material, such as the topic of this paper, Foreign Malign Influence (FMI). Machine learning algorithms use clustering methods, unsupervised learning, and statistical analysis to generate or simulate these mind-sets. By feeding AI real-world data, AI can identify distinct groups of people who respond to information in specific ways. This enables predictions on how these groups will behave when confronted with different types of foreign malign influence, making interventions more effective. Table 3 shows the simulation of three mind-sets of individuals responding to FMI information.

Table 3: AI simulation of three mind-sets, created on the basis of how they respond to misinformation presented by the FMI.

Exploring mind-sets in the context of FMI provides insights into social resilience and helps design better defense mechanisms against misinformation. Educational platforms can teach people how to recognize manipulation techniques based on their underlying mind-set. Furthermore, governments, social media companies, and other stakeholders can measure the effectiveness of counter- disinformation campaigns by targeting specific mind-sets and adjusting their message based on real-time feedback or simulation predictions from AI.

Phase 4: Predicting the Future by Looking Backwards

The “Looking Backwards” strategy is an innovative method for predicting trends and outcomes, inspired by Edward Bellamy’s “Looking Backwards” process. By mentally placing ourselves in 2030 and reviewing the events of 2024, we can distance ourselves from innate biases, misinformation, anxieties, and uncertainties of the present moment. This mental distance allows for clearer, more holistic insights into the trajectory of ongoing issues, such as foreign malign influences attempting to flood the U.S. with disinformation. Table 4 shows the AI simulation of looking backward from 2030.

Table 4: Predicting the future by looking backward at 2024 from 2030 to see what was done.

By looking back at 2024 from 2030, we can better assess the societal, political, and psychological ramifications of foreign influence operations, especially disinformation campaigns. By identifying the steps taken today that resulted in negative or positive outcomes by 2030, we might adjust our efforts now, fortifying our democratic resilience against foreign ideologies seeking to undermine our stability. This approach also holds potential when shared with the public, as it can help improve resilience and empower the democratic system to remain agile [22-26].

Phase 5: Creating a Briefing Document — Instructing the AI Both to Ask 60 Questions and Then to Summarize Them

In this step AI was instructed to create 60 questions, and provide substantive, detailed answers to each. The questions focused on various aspects regarding the impact of foreign disinformation on public opinion, civic engagement, and stability. These responses were then condensed into a more digestible briefing using summarizing tools like QuillBot [27-29]. This process allows for the inclusion of ideas and hypotheses that might not be immediately apparent to human analysts due to cognitive biases or blind spots [30,31] (Table 5).

Table 5: A simulated “set of five questions briefing document” about FMI, based upon the AI-generated set of 60 questions and answers, followed by an AI summarization of the results.

In the short term, AI-generated answers are objective and free from emotional bias, allowing analysts to base their next moves on data-driven insights. In the long term, AI technologies can be used for long-term planning and resilience strategies, allowing for rapid adjustment to evolving situations and trend recognition. This AI- driven approach also contributes to international cooperation against FMI, fostering a united front against foreign disinformation.

Discussion and Conclusions

The paper shows how the team developed a system using artificial intelligence, Mind Genomics, and real-time simulation capabilities to identify, counteract, and neutralize foreign malign influences (FMI). The system aims to understand the psychological and tactical mechanisms driving disinformation campaigns, and in turn generate strategic responses to reduce their efficacy.

AI simulations mimic real-world strategic meetings, interpersonal interviews, and situational dynamics, revealing the “human face” of the enemy and transforming large volumes of data into actionable intelligence. Mind Genomics thinking creates mind-sets, allowing for the identification of different tactics employed by adversaries. This allows mapping of a psychological landscape, understanding which messages take root and which defensive strategies resonate best with different audience segments. Real-time insights are crucial for adjusting countermeasures in sync with the adversary’s shifting methods.

The system has potential to influence public perception and bolster civic resilience by simulating the actions of enemy actors and the reactions of different segments of society. It could enable preemptive action, enabling policymakers and national security analysts to deploy specific public information campaigns or strategic maneuvers based on projections. The system’s broader geopolitical implications extend beyond national borders, creating a cooperative defense mechanism against foreign powers which exploit misinformation to sow international discord.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the ongoing help of Vanessa Marie B. Arcenas and Isabelle Porat in the creation of this and companion papers.

References

- O’Connell E (2022) Navigating the Internet’s Information Cesspool, Fake News and What to Do About University of the Pacific Law Review 53(2): 252-269.

- Schafer JH (2020) International Information Power and Foreign Malign Influence in In: International Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security; Academic Conferences International Limited.

- Weintraub EL, Valdivia CA (2020) Strike and Share: Combatting Foreign Influence Campaigns on Social The Ohio State Technology Law Journal 702-721.

- Wood AK (2020) Facilitating Accountability for Online Political The Ohio State Technology Law Journal 521-557.

- Rasler K, Thompson WR (2007) Malign autocracies and major power warfare: Evil, tragedy, and international relations theory. Security Studies 10(3): 46-79.

- Thompson W (2020) Malign Versus Benign In: Thompson WR (ed.), Power Concentration in World Politics: The Political Economy of Systemic Leadership, Growth, and Conflict. Springer pp. 117-142.

- Tromblay DE (2018) Congress and Counterintelligence: Legislative Vulnerability to Foreign Influences. International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence 31(3): 433-450.

- Lehmkuhl JS (2024) Countering China’s Malign Influence in Southeast Asia: A Revised Strategy for the United Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs 7(3): 139.

- Bennett WL, Livingston S (2018) The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication 33(2): 122-139.

- Bennett WL, Lawrence RG, Livingston S (2008) When the Press Fails: Political Power and the News Media from Iraq to University of Chicago Press.

- Wagnsson C, Hellman M, Hoyle A (2024) Securitising information in European borders: how can democracies balance openness with curtailing Russian malign information influence? European Security 1-21.

- Feuston JL, Brubaker JR (2021) Putting Tools in Their Place: The Role of Time and Perspective in Human-AI Collaboration for Qualitative Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 5(CSCW2): 1-25.

- Jiang JA, Wade K, Fiesler C, Brubaker JR (2021) Supporting Serendipity: Opportunities and Challenges for Human-AI Collaboration in Qualitative In: Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 5(CSCW1): 1-23.

- Rafner J, Gajdacz M, Kragh G, Hjorth A, et al. (2022) Mapping Citizen Science through the Lens of Human-Centered AI. Human Computation 9(1): 66-95.

- Aswad EM (2020) In a World of “Fake News,” What’s a Social Media Platform to Do? Utah Law Review 2020(4): 1009.

- Garon JM (2022) When AI Goes to War: Corporate Accountability for Virtual Mass Disinformation, Algorithmic Atrocities, and Synthetic Propaganda. Northern Kentucky Law Review 49(2): 181-234.

- Hartmann K, Giles K (2020) The Next Generation of Cyber-Enabled Information 2020 12th International Conference on Cyber Conflict 233-250.

- Brownsword R (2018) Law and Technology: Two Modes of Disruption, Three Legal MindSets, and the Big Picture of Regulatory Indian Journal of Law and Technology. 14(1): 30-68.

- Dang J, Liu L (2022) Implicit theories of the human mind predict competitive and cooperative responses to AI Computers in Human Behavior 134: 107300.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006) Founding a New Science: Mind Journal of Sensory Studies 21(3): 266-307.

- Papajorgji P, Moskowitz H (2023) The ‘Average Person’ Thinking About Radicalization: A Mind Genomics Cartography. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology; 38(2): 369-380.

- Levinson MH (2005) Mapping the Causes of World War I to Avoid Armageddon ETC: A Review of General Semantics 2(2): 157-164.

- Rapoport A (1980), Verbal Maps and Global Politics. ETC: A Review of General Semantics 37(4): 297-313.

- Rapoport A (1986) General Semantics and Prospects for Peace. ETC: A Review of General Semantics 43(1): 4-14.

- Sadler E (1944) One Book’s Influence Edward Bellamy’s “Looking ” The New England Quarterly 17(4): 530-555.

- Vincent JE (2011) Dangerous Subjects: US War Narrative, Modern Citizenship, and the Making of National Security 1890-1964 (Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

- Bayatmakou F, Mohebi A, Ahmadi A (2022) An interactive query-based approach for summarizing scientific documents. Information Discovery and Delivery 50(2): 176-191.

- Fan A, Piktus A, Petroni F, Wenzek G, et al. (2020) Generating Fact Checking Briefs. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing 7147-7161.

- Fitria TN (2021) QuillBot as an online tool: Students’ alternative in paraphrasing and rewriting of English writing. Englisia: Journal of Language, Education, and Humanities 9(1): 183-196.

- Radev DR, Hovy E, McKeown K (2002) Introduction to the Special Issue on Computational Linguistics 28(4): 399-408.

- Safaei M, Longo J (2024) The End of the Policy Analyst? Testing the Capability of Artificial Intelligence to Generate Plausible, Persuasive, and Useful Policy Analysis. Digital Government: Research and Practice 5(1): 1-35.