Abstract

The Grand Canyon of the Colorado River is the traditional homeland of many Native American peoples, including the Southern Paiutes, Hualapai, Havasupai, Zuni Pueblo, Hopi Pueblo, and Navajo. Many massive volcanoes with widespread lava flows have been witnessed by these Native Americans over the past 40,000 years, so their various cultural understandings and ceremonial responses to volcanism are grounded in experience. Pilgrimage is one example of a persistent ceremonial response to volcanic areas by Native American peoples. This analysis is based on 902 ethnographic interviews with Paiute elders conducted over decades by the authors. The Paiute response to volcanism is typical of Native Americans in the Southwestern United States but manifests itself uniquely in the geology of the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River. The analysis argues that these are heritage places and landscapes to be protected by the IUCN World Conservation Congress (IUCN 2024) which is where the world comes together to set priorities and drive conservation and sustainable development action. More than 9,000 people participated in the 2021 Congress in Marseille. Experts shared the latest science and best practice, and IUCN Members voted on 39 motions to guide humanity’s relationship with our planet for the decades ahead.

Keywords

Volcanic cultural heritages, Geosites, Geoscapes, Geoheritage, Native Americans, Southern Paiutes aboriginal lands, Grand Canyon, Colorado river

Introduction

Piapaxa ‘uipi: The river there is like our veins. Some are like the small streams and tributaries that run into the river there. So the same things; it’s like blood- -it’s the veins of the world… This story has been carried down from generation to generation. It’s been given to them by the old people… it would be given to the new generation, too… (San Juan Southern Paiute elder, (interviewed about the Colorado River at Willow Springs, September 27, 1993).

The analysis contributes to the burgeoning academic literature that has responded to the United Nations’ call for the identification of geological places and landscapes as cultural heritage deserving preservation [1]. The ICUN and the WCPA have a Geoheritage Specialist Group that has documented the need for such new heritage preservation approaches [2]. That literature is illustrated by the 20 published peer reviewed papers in the Special Issue of the journal Land entitled Geoparks, Geotrails, and Geotourism – Linking Geology, Geoheritages, and Geoeducation edited by Brocx and Semenluk (2022) [3]. This Special Issue included studies from Europe, Australia, USA, Latin America, and Asia. Subsequently, published articles on this topic are illustrated by Geoheritage and Cultural Heritage Overview of the Toba Caldera Geosites, North Sumatr, Indonesia [4]. These studies [5] document a range of complexities involved in preserving, interpreting, and managing complex geoheritage. The Geology profession through the International Commission on Geoheritage [6] has responded by identifying significant geosites around the world using both their importance to science and to humans as criteria [6]. This analysis describes a long Native American pilgrimage trail that has been used for tens of thousands of years and located north of the Grand Canyon in Arizona. The analysis is based on 902 ethnographic interviews of which 149 interviews were conducted specifically in the study area. Interviews on this topic were conducted with Southern Paiute elders over decades with the authors. Especially important are two points (1) the pilgrimage trail is responsive to massive volcanic activities that have produced major lava flows, lava dams, and lakes in the Grand Canyon Colorado River Corridor (Figure 1 and 2) the analysis illustrates the need for holistic geoheritage understandings of Native American pilgrimage routes including the spaces between places, the presence of functionally integrated geosites along the routes, and multipurpose ceremonial destinations.

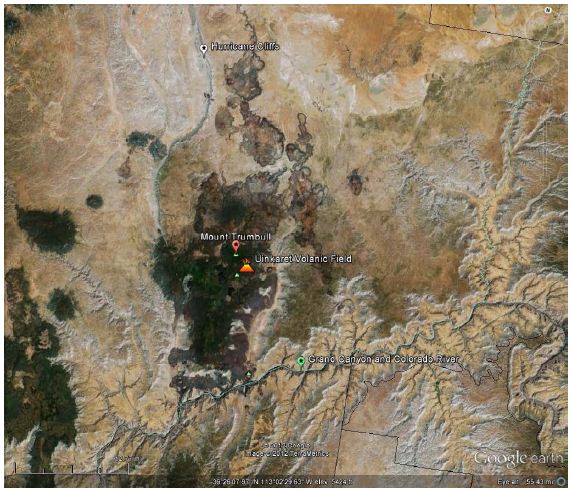

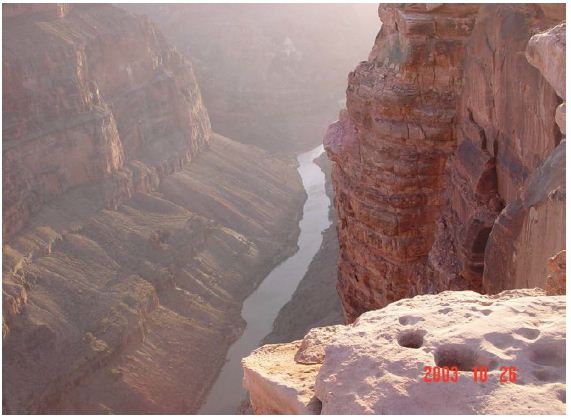

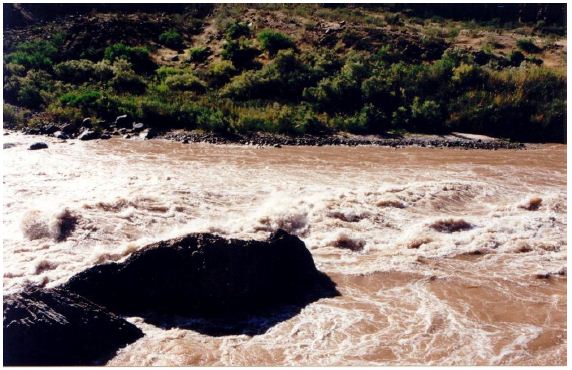

Figure 1: The Colorado River’s flow through the Grand Canyon

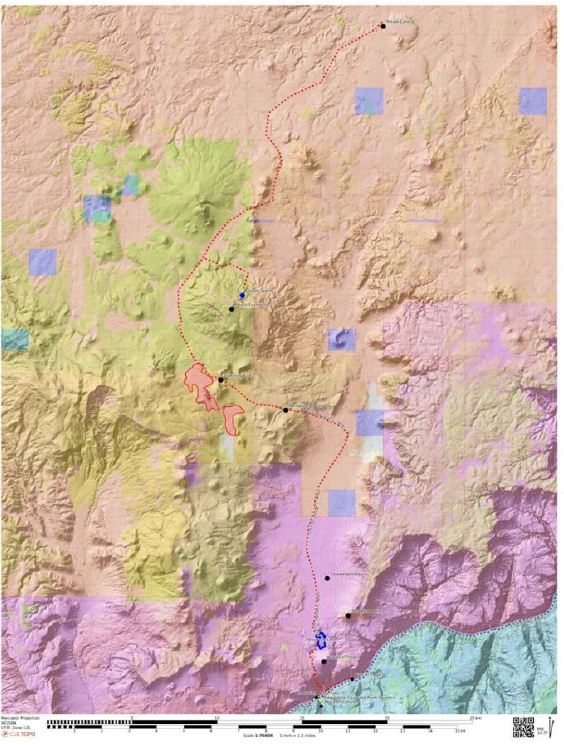

Figure 2: The Uinkaret Volcanic Field, the Grand Canyon, and the Colorado River

A Paiute described the Colorado River as a living cultural resource as follows:

Piapaxa ‘uipi: The river there is like our veins. Some are like the small streams and tributaries that run into the river there. So the same things; it’s like blood- -it’s the veins of the world… This story has been carried down from generation to generation. It’s been given to them by the old people… it would be given to the new generation, too (Stoffie et al. 1994) [7-8]. The focus of the analysis is the Uinkaret volcano field (the dark areas centered in Figure 2), which is a central component of USA federal lands managed by the following agencies: (1) the Grand Canyon National Park, North Rim Unit (NPS); (2) Grand Canyon – Parashant National Monument, (NPS and Bureau of Land Management); (3) Arizona Strip Bureau of Land Management (BLM); and (4) the Grand Canyon Colorado River Corridor, Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) (Figure 3). The analysis documents challenges associated with accurately knowing about, interpretating, and conducting culturally sensitive management of this and similar spatially long and temporarily deep Native American heritage areas. Management issues are dominated by problems of Environmental Communication especially when this involves Epistemological Divides [9].

Figure 3: USA Federal Land Jurisdiction Map

This analysis is situated within the greater Uinkaret volcanic field and its related geosites and geoscopes (Figure 4). Using this geographic focus, this analysis aims to understand and elaborate upon the cultural understandings of the greater Uinkaret geoscape by Southern Paiute people, as well as their deep heritage connections to this aboriginal land. These heritage connections are further situated in time with new, scientifically backed occupation dates for Native People in the Southwestern United States of about 40,000 years Before Present (BP). The temporal frame for this heritage analysis is operationally defined as the late Pleistocene, which occurred between 128,000 BP and 11,700 BP, as well as the Holocene, which has occurred from 11,700 BP through modern times. Scientific studies have placed Native Americans in the region at least by 37,000 BP with the geoarchaeology dates of 23,000 to 21,000 BP at White Sands National Park in New Mexico [10-11] and 38,900 to 36,250 BP at the Harley Rock Shelter on the Rio Puerco, New Mexico [12]. These new geoscience dates indicate that Indigenous Peoples experienced this area as both a massive wetland filled with lakes, rivers, and swamps and then as an arid desert with intermittent streams, sand dunes, small artesian springs, and heritage playas.

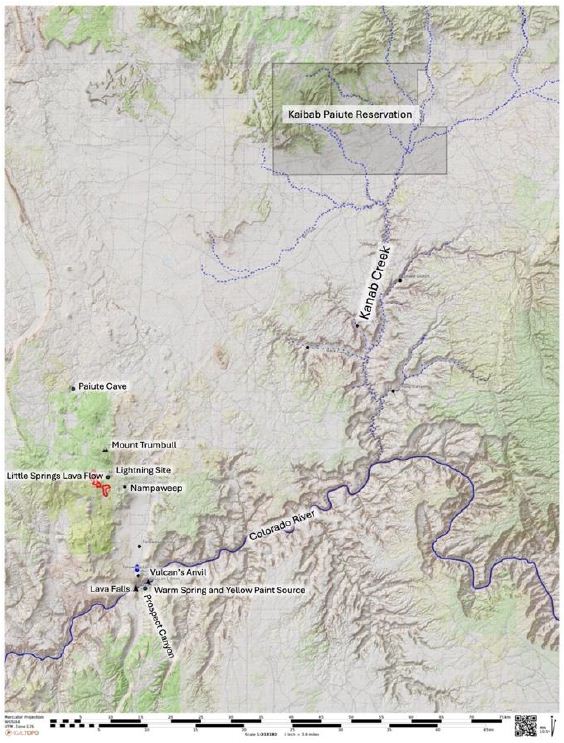

Figure 4: Geoscape and Southern Paiute Aboriginal Lands North of the Grand Canyon

The data used in this analysis argue that the Uinkaret volcanic study area contains a Native American heritage landscape that is best understood as being composed of geosites and geoscapes, also known as geoheritage [1, 13] as defined by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature [14]. The concept of heritage landscape implies that both natural and cultural components combined over time to produce a phenomenon that is clearly located somewhere and can be considered for identification and protection by contemporary nations and the guidelines of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature [14]. Native people argue that their traditional volcanos, lava flows, hot springs, charismatic viewscapes, the Grand Canyon, and the Colorado River all have been alive since Creation, and they remain so today. Native Americans argue that these geosites and geoscapes are key to their contemporary heritage because these contain the songs, prayers, ceremonies, and memories of ancestors who lived in this area since Creation.

Geoscapes of the Uinkaret Volcanic Field

The geology of the western Grand Canyon (Figure 5) represents what is perhaps the most spectacular three-dimensional display of volcanological processes in the world [15]. The dramatic sight of frozen basaltic lava falls cascading over the Canyon’s inner gorge was first documented during John W. Powell’s initial expedition into the region in 1869 [16]. The Uinkaret volcanic field is a tectonically controlled lava field whose southern reaches meet with both the Colorado River and Grand Canyon. Over the past two million years, lavas have erupted from both fissures and central vents, forming the volcanic field [15]. Mount Trumbull and its associated lava flows and volcanoes are located within the northern portion of the large Uinkaret volcanic field [17-18]. The Uinkaret lava field lies 120 km south of St. George, Utah, and is tectonically defined by two major normal faults — the Hurricane to the west and the Toroweap to the east. At its southern reaches where the Uinkaret volcanic fields borders the northern rim of the Grand Canyon, there are cinder cones that have produced lava flows that have repeatedly cascaded into the canyon, creating temporary lava dams [19]. While most of the volcanic activity in the Uinkaret volcanic field dates to the Pleistocene, some of the volcanic activity has been dated later to the Holocene including about 1000 AD [20].

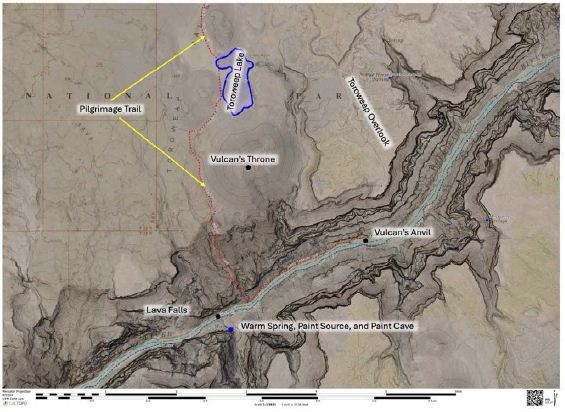

Figure 5: Uinkaret volcanic field where it meets the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River, with pilgrimage trail marked in red.

The latest lava flows that erupted close to the northern edge of the Grand Canyon’s rim flowed down and formed cascades over 900 meters high [15, 21]. In addition to this activity, multiple vents erupted within the canyon itself. The products of this activity effectively dammed the Colorado River a total of 13 times – the remnants of which are still visible along the canyon walls today. The largest of the dams formed a 700-meter-deep lake which extended upriver into present day Utah [21-22, 23].

Paiute Epistemology

The ways in which societies relate to their environments are grounded in their epistemologies. In Southern Paiute society, relationships and deep connections with the environment were formed during Creation. Southern Paiutes maintain that the Creator gave them the responsibility and the rights to manage their environment to promote environmental growth and sustainability. To fulfill these responsibilities endowed upon them since Creation, over tens of thousands of years, they have developed numerous strategies and activities that increase biodiversity and biocomplexity throughout their homeland. The basic tenets of Southern Paiute epistemology have helped forge the relationship they have with their environment. To Southern Paiutes, the universe is alive and everything is interconnected through all types of relations, what anthropologist Roy Rappaport (1999: 263-271; 446) [24] calls “the ultimate sacred postulate.” The universe is alive in the same way that humans are alive, and the universe possesses most of the same anthropomorphic characteristics as well. The universe has discrete physical components such as power and elements. It is a living system. This concept of the living universe is so fundamental that any discussion of Southern Paiute culture cannot occur without it.

As explained by Liljeblad (1986: 643-644) [25], to the Southern Paiutes, power is everywhere and is “a source of individual competence, mental and physical ability, health, and success.” Power is referred to as Puha. This concept is similar to that of many different tribes living throughout the western United States. Other Numic language speaking people, such as the Ute, Western Shoshone, Owens Valley Paiutes, and Northern Paiutes have similar words. In his article, “Basin Religion and Theology: A Comparative Study of Power (Puha),” Miller (1983: 79-89) [26] noted that: Ute- Puwavi, Western Shoshone- Puha and Poha, Northern Paiute- Puha, the Chemehuevi and Southern Paiute- Puhaare the same people with a common language. The term for Puha is the same among all of these cultural groups. Alternate spellings aside, Puha is a fundamental principle of each of their epistemologies as well. The concept of spiritual power is not limited to the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau peoples, however; it is also a core epistemological principle in the cultures of nearby Upland and Colorado River Yuman-speaking peoples such as the Mojave, Hualapai, and Havasupai. According to Numic beliefs, Puha is derived from Creation and permeates the universe, which resembles a spider web. Sometimes it is like a thin scattering, and at other times it occurs where there are clusters of life in definite concentrations with currents. Puha exists throughout the universe, but varies in intensity from person to person, place to place, element to element, and object to object. This is similar to how strength differs among humans. Puha can also vary in what it can be used for, and it determines the tasks certain elements (air, water, rocks, plants, animals) can perform or accomplish. Puha is networked; it connects, disconnects, and reconnects elements in different ways. This occurs because of the will of the elements that have the power. Puha is present in and can move between the three levels of the universe: the upper level— where powerful anthropomorphic beings live, the middle level—where people live now, and the lower level—where extraordinary beings with reptilian or distorted humanoid appearances live [27].

Power is diffused everywhere in continuous flux and flow, which, however, is not haphazard because, as an aspect of memory, power is rational. From all available evidence, the routes of concentrated power within generalized dispersion are web-like, moving both in radial patterns and in recursive concentric ones, out from the center and back again… The web image is reflected in the stories where Coyote assumes the form of a water spider to carry humans to land and Sun takes the form of a spider who is webbing the firmament of the universe… The web of power, however, is not static like that of a spider because the webbing actually consists of the flow of power rather than filaments per se. Rather, the web is pulsating and multidimensional, even having aspects of a spiral, sometimes regular and sometimes erratic, intersection with the radials from the center. This spiral movement is represented most graphically by an in-dwelling soul of a person that can be seen escaping the body at death as a whirlwind. While operating in a dynamic equilibrium within the universe, Puha is also entropic [27-29]. This means that over time, Puha has gradually diminished since Creation in quality, quantity, and availability. The reason for this is that human beings at various times treated it improperly, and failed to uphold their responsibilities in the relationship they have with the interdependent system. Indigenous people believe that a very rapid loss of Puha occurred after the European encroachment. Knowledge concerning how to regulate relationships with powerful elements was lost through the processes of colonization. Despite this, Puha is always retrievable in some form, as long as new guidelines are established for obtaining, maintaining, and respecting it. In Southern Paiute culture, there are rules for handling Puha and powerful objects. These rules function to control the person with the Puha and prevent him or her from misusing it in one of two ways. First, power can only be used at proper times and places and must be used in accordance with standardized procedures, such as preparation and pilgrimage to ceremonial areas. Secondly, people who have obtained and controlled Puha and its knowledge may withhold information on procedures for acquiring and maintaining power from uninitiated persons or persons who are deemed unworthy candidates.

As Stoffie, Zedeño, and Halmo (2001: 65) [27] wrote, “the diversity and unpredictability of power was consistent with an ecosystem that was equally diverse and unpredictable, although often kind and bountiful in the resources provided.” In her ethnography of the Northern Paiute – a tribe that is culturally and linguistically similar to Southern Paiutes – Catherine Fowler (1992: 170-172) [30] described how the people of Fox Peak believe Puha is present in all elements of the Earth:

One of the most basic beliefs that guided the interactions of people with the land and its resources was the concept that the Earth was a living being, just as were the Sun and Moon, the Stars and natural forces such as Water, Wind, and Fire. The life force within all of these, as well as particular geographic features and classes of spirit beings, was power (Puha)… Although power potentially resides anywhere, its association with mountains caves, spirits or other water sources, and the results of past activities by Immortals or humans was particularly apparent.

This discussion of Puha in her ethnography emphasizes that power concentrates in all aspects of the universe and serves as the life force in these elements as well. Fowler also notes that power is attracted to special people who can channel it and use it during prayer and ceremony. For Numic-speaking peoples of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau, this concept and understanding of Puha frames how they relate to, understand, interact with, and use the lands around them.

Puha and Ceremony

People use Puha in a number of different ceremonies, each of which occurs in a unique place and thus requires people to seek those places out for ceremony. One type of place that people visited for ceremonies was one where they could perform activities that brought individuals, communities, and the world in balance, also known as Round Dances. A suitable place for a ceremonial Round Dance required a large, flat space that had associations with Creation. Round Dance sites are found throughout the Great Basin and the Southwestern United States, and they can be sites that involve human participants or animal participants. The ceremony involved a large number of people, all of whom have traveled some distance away from their home community. One Round Dance site is the Rabbit Circle Dance site in the Spring Mountains [31]. Its name reflects the Southern Paiute belief that the site was used by Rabbit, a Creator being, in the mythic times to balance the world.

Other significant Round Dance places in southern Nevada are Corn Creek, Indian Springs, and Wellington Canyon. Another well documented Round Dance site is found near Kanab, Utah. On January 6, 1872, John Wesley Powell and Fredrick Dellenbaugh saw a Round Dance at this site. Dellenbaugh stated that the entire Kaibab Paiute band was camped together, which at the time would have been approximately 200 people. At the center of the dance circle was a cedar tree with most of its branches removed. All that remained was a tuff at its top. The entire group formed a large circle around the tree and danced and sang. A man who was in charge led the group in song and stood at the center of the dance circle [32]. Round Dances were performed seasonally in order to keep the world in balance. Some Round Dances took place following the harvest of planted crops or the gathering of wild plant resources like pine nuts or agave. There were other types of Round Dances performed on an irregular basis such as the Ghost Dance, when extraordinary forces seemed to place the world more out of balance than normal [33-34]. Some ceremonies, like pilgrimages, were performed by a small number of specialized shamans. These activities required physical and spiritual preparation to handle being isolated from normal daily lives, and for making the long difficult journey to high mountain peaks. Shamans also needed to be prepared to acquire large amounts of power during their ceremonial trek. Southern Paiute shamans went on pilgrimage for two predominant reasons—rites of passage activities for young males, and for obtaining knowledge and power to be used in doctoring and balancing ceremonies. The knowledge and power they gained during these ceremonies aided their communities, districts, and the entire Southern Paiute nation. Puha’gants, or the shamans who journeyed for themselves and their communities, gained the knowledge to conduct rain making ceremonies, heal the sick, and put the world in balance.

Puha and Volcanism

Volcanos have a special place in Southern Paiute epistemology, and Southern Paiute people are strongly culturally attached to volcanic places and events. Volcanic episodes are distinctive moments when Puha moves from lower to higher levels of existence, causing the power to accumulate in these areas [35-41]. Puha moves from the lower portions of the Earth to form hot springs, mountains, volcanic cones, basalt mesas, lava tubes, basalt bombs, and obsidian deposits. Volcanic places and materials play important roles in the formation of special minerals and biotic communities found here. Some resources can be found only where volcanic activity has created power landscapes. Southern Paiute people respect and interact with places of volcanic activity; because these places contain powerful forces and spiritual beings who can help balance human society at local, regional, and world levels. As one Southern Paiute elder said, “Volcanoes are sacred mountains. The old people knew it was alive, like the mother earth is alive. We have a song about the rocks shooting out of a volcano near home,” [42]. Places that contain volcanic activity are considered sacred and powerful. Numic peoples believe that volcanic events are moments when Puha deep inside the Earth is brought to the surface as a way for the land to renew itself or be reborn. Volcanism is also a way for Puha to be distributed across a landscape. Above ground, Puha follows the flow of water and distributes itself across a landscape. This distribution occurs similarly below the surface, where Puha follows the flow of magma rather than that of water. As Puha moves through underground channels, it distributes itself and connects volcanic places over vast distances.

Methods

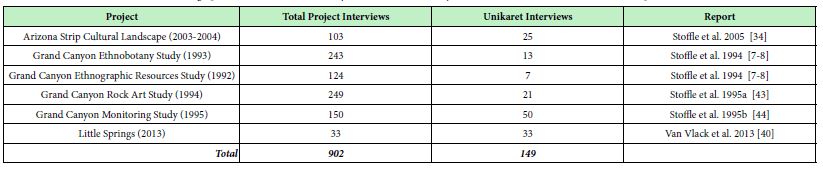

BARA ethnographers collected cultural interpretations about natural resources, places, and landscapes by using both formal and informal interviewing techniques. These data gathering instruments have been drafted, approved by tribal governments, and applied in nine ethnographic studies of volcanic landscapes. This report is primarily based on such interviews conducted at field sites chosen as part of the six ethnographic research studies that are listed in Table 1, which presents the number of formal and informal interviews. Interviews are defined as a conversation between an ethnographer and a cultural representative during which information specific to the project is shared and recorded. Most interviews were guided by a set of prewritten, culturally sensitive questions, but informal interviews occurred when these types of formal interviews were not possible or appropriate. Informal interviews and discussions can occur for various reasons, with one of the most common reasons being that the ethnographer and the cultural representative are walking to or from a geosite that is being studied. Either the place or the conversation may elicit a response that is relevant to some cultural dimension of the study. In most cases, the information is offered at a time when it is difficult to record, and the ethnographer instead records a personal account of the conversation. Informal interviews are a common and important source of cultural information and have occurred throughout these studies. A number of formal interviews were conducted with survey instruments during six ethnographic studies. The spatial extent of these studies exceeded the narrower focus of this Uinkaret analysis, so of the 902 total interviews, only 149 interviews were conducted in areas specifically considered in this analysis. It is important to note, however, that cultural interpretations from places in the vicinity of the Uinkaret volcanic field were conducted with Southern Paiute tribal representatives, and therefore these other interviews helped to situate the Uinkaret data. Issues such as the purpose of pilgrimage and the cultural reasons for visiting kinds of geosistes were components of all 902 Grand Canyon Colorado River Corridor and Arizona Strip interviews (Table 1).

Table 1: Ethnographic Studies Used in This Analysis from the Grand Canyon Colorado River Corridor and Arizona Strip Studies.

Confidence in interview findings, and thus this analysis, increases with the number of interviews that occur at a given place. In general, four interviews with the same form are required at each geosite for a minimal confidence level to be achieved. Four to 11 interviews were conducted at all sites. It is important to note that a few quotes were used in this analysis to represent both the primary and alternative interpretations of geosites. In any ethnographic study, participating tribal governments may request that some other interpretations remain confidential and not be used in technical reports. Such was the case on several occurrences with the studies that make up this report, so the requests of the tribal governments have been respected and these confidential interpretations have not been presented here, nor in past reports pertaining to the same studies. To further preserve the integrity of culturally significant places, the data of geosites is deliberately vague unless they are already marked on public maps. The vague locations are used to protect less well known culturally sensitive resources. Tourism is a critical threat to all geosites involved in the studies. The public copies of the study reports were reviewed by the participating elders and their tribal governments.

The Uinkaret Volcanic Case Study

There are spatially large geoscapes that involve hundreds of geosites that are connected by an extensive network of spiritual and physical trails. The following section is a reconstruction of two ceremonial geoscapes found near Mount Trumbull in the southcentral portion of the Arizona Strip. This analysis is based on geosite and geoscape interpretations made by Southern Paiute elders who participated in ethnographic studies and the interpretations of many others over the last forty years. Some of the geosites have cultural meaning and ceremonial roles in other geoscapes creating what can be best be described as an overlapping mosaic of nested geoscapes. Therefore, it is always important to think of Native American geoscapes and geosites in terms of having multiple cultural meanings for Native Americans with meanings that are both established at the same and different time periods. Mount Trumbull is connected to two local geoscapes. The first focuses on a pilgrimage to Toroweap Overlook (and Vulcan’s Throne) at the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. The second geoscape is a pilgrimage to a ceremonial landscape at Vulcan’s Anvil at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. Both geoscapes involve trails along the pilgrimage which lead to Mount Trumbull, followed by a visitation at Coyote Spring. One landscape, and perhaps both given the spiritual needs of the pilgrims, involves purification, acquiring Puha, and Puha’pah (power water) at Little Spring. These places have been interactive since they fundamentally conclude where past lava flows from the North Rim have filled the Colorado River— from top to bottom forming a massive upstream lake. Evidence of former lava flows exist in abundance at the Vulcan’s Anvil, Vulcan’s Throne, and Lava Falls.

Northern Pilgrimage Trail

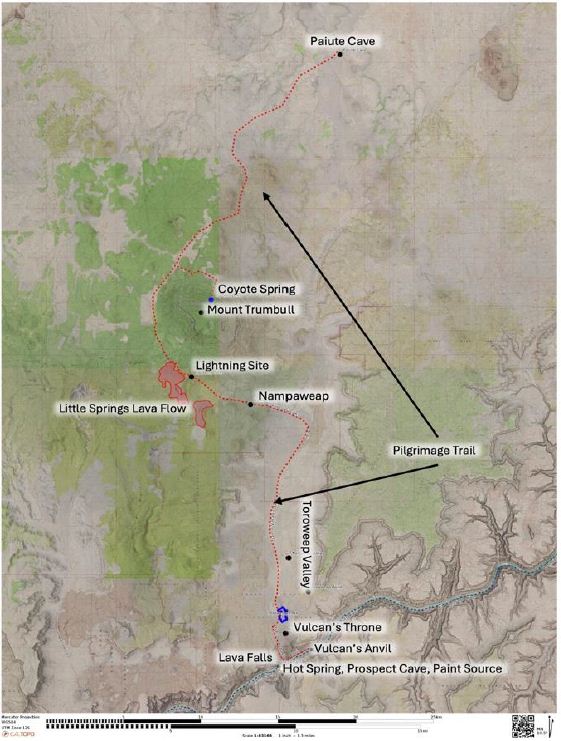

This northern portion of the Uinkaret geoscape (also called the Arizona Strip) contains five geosites: (1) Coyote Springs, (2) Paiute Cave, (3) Little Springs Lava Flow and Hot Spring, (4) Nampaweap, and (5) Vulcan Volcano and Toroweap Overlook which are looks on the edge of the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, above Lava Falls (Figure 6). For Southern Paiute people seeking visions, spirit helpers, or medical cures, each of these places has a unique function. In addition, each place is sequentially linked, thus creating a ceremonial pilgrimage landscape that is integrated in terms of time, function, and space. For this geoscape, we consider the hypothesis that Southern Paiutes might not have been the only people using this area. Other Indigenous groups, such as the Hopi, Havasupai, and Hualapai may have also used the Mount Trumbull area for ceremony. As an example, it is well documented that the Hualapai frequently traveled across the Grand Canyon to participate in joint ceremonies with Southern Paiute people [45]. There are a total of twenty-three traditionally used trails across the Colorado River where it passes through the Grand Canyon making access possible [46]. Based in part on his work with Dan Bulletts, Stoffie (1982: 124) [47], wrote that “Trails tied Indian people together affording a regular exchange of goods, services, innovations, news, marriage partners, and occasionally warring parties. It is no wonder, then, that trails and often the people who used them became culturally significant.”

Figure 6: Northern Mount Trumbull Geoscape

Paiute Cave

Southern Paiute representatives and UofA ethnographers visited a place located 15 miles north of the Little Springs Lava Flow and Mount Trumbull [42]. This site, known as Paiute Cave (Figure 7), is part of the northern portion of the Uinkaret Lava Field. The cave is found at the base of a large volcanic deposit which is bordered by the eastern edge of the Uinkaret Plateau. Given its geological composition and cultural resources, this cave is linked to ceremonial activity at the Little Spring Lava Flow and to geosites in the Grand Canyon.

Figure 7: Entryway to the Paiute Cave

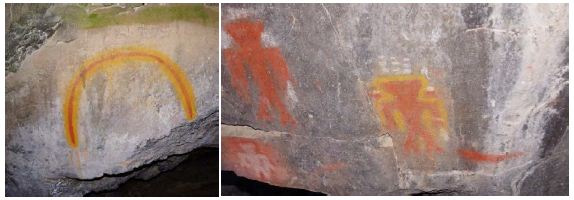

Paiute Cave is a collapsed volcanic lava tube. The area around and on top of the cave is part of a large pyroclastic deposit. These types of deposits are characterized as being cinder, bomb deposits, and reddish-gray, black, red, and gray tuff. These deposits are found near a pyroclastic cone. This cone is located near one or more vents that overlap the coalescing basalt flows [19]. Paiute Cave is one of these volcanic vents. Volcanic vents allow air to flow from deep inside the air outward which from a Southern Paiute perspective is a testament to the Earth breathing and being an active living entity. Caves in Southern Paiute culture are understood as powerful sacred places. Caves in general are deemed important because they provide shelter and collect water—both vital for all life. Caves also tend to be dark and moist like what Miller (1983) [26] refers to as the initial world. Caves have been described by Southern Paiute religious leaders as being the mouths of mountains [27]. Additionally, Liljeblad (1986) [25] noted that caves were often used during power acquisition ceremonies and that caves served as entrances to underground pathways. Each cave has its own purpose, and thus, no two caves can be considered the same. Caves were used by Puha’gants (medicine men) to gain spirit helpers or knowledge such as songs or prayers. Paiute Cave is unique in that it contains red, yellow, and white painted figures at various locations inside the cave which indicates that the cave was used for ceremonial activity (Figure 8). Tribal representatives maintain that the ceremonial activities conducted at Paiute Cave were linked to the Little Spring Lava Flow and Puha acquisition.

Figure 8: Red and Yellow Figure on the Left side of the Cave (L) and Painted Cave Figure on the Back Wall (R).

As one travels south from Paiute Cave towards Mount Trumbull, the valley becomes bounded by high volcanic mountains and lava flows. These types of constrictions are important physical attributes to Southern Paiute pilgrimage trails, because culturally narrow and constricted spaces influence cultural meaning and affect the movement of natural elements like wind and water. Pilgrimage trails pass through these narrow spaces because these are areas where Puha converges and collects in a manner similar to how water will pool in constricted places. As a trail passes through these types of locations, a pilgrim can experience and draw upon the power of the area as he or she progresses on the journey.

Coyote Spring

Ceremonies are conducted at places with high concentrations of puha, too dangerous for non-religious specialists to stay for long periods at ceremonial places. Therefore, people who use a ceremonial area must have had to travel to it from safe home bases. Southern Paiutes would have come from oasis-based agricultural villages located away from ceremonial places elsewhere, like those located north of Mount Trumbull in the Kanab River area, the Virgin River area near present-day Zion National Park, and the Santa Clara River area [48- 50]. People traveling to the Mount Trumbull area traveled major trails, many of which have since been given Anglo names as a result of the frequency with which Euro-Americans traveled these trails during the exploration and expansion periods. These old Indian trails cut across large portions of Arizona, Utah, Colorado, and Nevada. The Mormon Temple Trail, the Honeymoon Trail, and the trail used by Escalante and Dominguez were originally Indian trails. These were the kinds of trails that would have been taken by people en route to the Trumbull area for ceremony in the Coyote Spring located on the southwestern flank of Mount Trumbull. The nearby Uinkaret Pueblo was formed in part from volcanic stones. When people traveled to the Mount Trumbull area for ceremonies, it was not uncommon for their families to come too. The families would have stayed in the Coyote Spring area while the others went on their pilgrimage. It would have been too dangerous for family members to accompany the pilgrims to the ceremonial places. These puha places were only visited by types of people who have certain amounts of puha and had begun a long series of preparations prior to arriving in the Mount Trumbull area. The people who remained at Coyote Spring carried on with daily activities while the pilgrims were away. Depending on the time of year, the families would have gathered different kinds of plants, like three- leaf sumac, cedar, or pine nuts. Family members could also take this opportunity to hunt animals like deer, rabbits, elk, or antelope.

Little Springs Flow and Hot Spring

The pilgrims traveled south to Little Springs Lava Flow and hot spring, which were produced by a recent basaltic lava flow. This analysis is shorted because information regarding this geosite has been published elsewhere [40-42, 51]. Pilgrims would have interacted with the lava flow spring to cleanse and purify themselves for their journey. The hornitos located throughout the lava flow would have been places for sweat lodges and the lava rocks are well suited for holding heat. Indian people have formed miles of trails on top of the lava flow connection places near the Hornitos. Pilgrims prepared for ceremony and travel by singing songs and saying prayers to the lava flow, the surrounding volcanic mountains, the water, the plants, and the animals. They asked for a safe journey to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon where some ceremonies were conducted. Water was taken from the spring and brought with them to Nampaweap where it would have been used in ceremony and left as an offering.

The Lighting Site

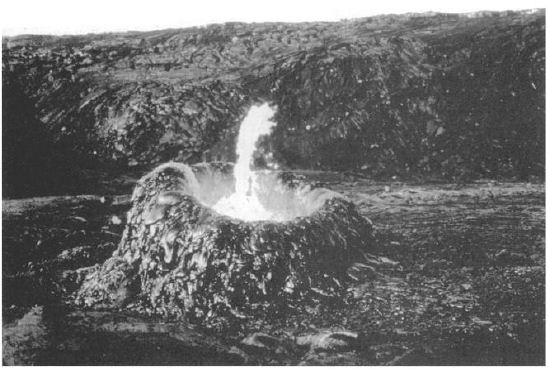

The Lighting Site is an enclosed and one roofed structure whose walls are formed of volcanic boulders carried from the Little Spring volcanic flow. Some of the boulders were made by puha’gants at hornitos (Figure 9) on the active lava flow at the time of the eruption [42]. The process of going on to active lava flows and making artifact boulders from splashes of lava at hornitos is documented for Sunset Crater [52]. There the boulders were imprinted with corn whereas at Little Spring the puha’gants placed ceramic pots on the edge of the hornito. These are generally called sherd rocks whereas at Sunset Crater they are called corn rocks. At both locations the artifact rocks were subsequently taken away and made into a structure used for ceremonies. Many Native American cultures had religious specialists who gathered, used, and prayed with volcanic rocks. Round volcanic rocks are often used in the Sweat Lodge fires where they are called Grandfather Rocks. These boulders and the places where they were taken are extremely sacred because they contain pottery sherds deriving from that ceremonial connection of a volcanic source and a human artifact. This site is not further discussed here due to its cultural sensitivity. The site continued to be used for ceremonies long after the eruption and is visited by tribal members today.

Figure 9: Hornito at Kilauea Volcano, Hawai’i for a Visual Example (Elson et al. 2002)

Nampaweap

From Little Springs, the pilgrims would travel roughly three miles to Nampaweap; a small basaltic canyon that constricts the trail to the North Rim. The upper portion of the canyon has a series of peckings, a rock shelter, and a spring, and thus it has high concentrations of puha. The pecking were interpreted as associated with Origin Stories given some pecking were only used where such stories were recounted. The Ocean Woman’s Net is in the upper left of the image below (Figure 10). When people came to Nampaweap, they would have first offered the place water brought from Little Springs, and then explained the purpose of their visit and asked for the puha they need to continue to the North Rim.

Figure 10: Peckings found at Nampaweap, Ocean Women’s Net Upper Left

According to representatives the small canyon provided a song to be sent to the big canyon and used during the ceremony at that place. Additionally, more water was collected from the spring found above the rock art panels. It would have served both as an offering and for members of the vision quest, support camp at the North Rim.

Toroweep Overlook and Vulcan’s Throne

Following prayers at Nampaweap, people traveled east towards Toroweap Valley and then south towards the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, covering a distance of twelve miles. While traveling, the pilgrims continued to pray and announce to the canyon and the mountains why they were there, and they would ask for permission to enter the area. The people would have been given a sign, like an eagle flying by that would have signaled they had permission to enter the area. Upon reaching the north rim of the Grand Canyon and receiving permission to enter, the vision seekers could go to either one of two locations to obtain their vision — Vulcan’s Throne or Toroweap Overlook. From these locations, there are impressive views of the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River (Figure 11).

Figure 11: The Toroweap Overlook View Down into the Colorado River

Vulcan’s Throne is a pure cinder cone volcano located on the North Rim. This volcano erupted on five separate occasions and is recognized as a port of the volcanic system that was responsible for filling the Grand Canyon with lava twelve times during the last 1.2 million years. The lava flows created a series of dams in the Grand Canyon which were responsible for creating a series of lakes in the canyon that extended to the head of today’s Lake Powell. The Vulcan’s Throne flow was approximately eight to ten miles long. The flows from Vulcan’s Throne are some of the oldest and largest in terms of volume in the Grand Canyon (Hamblin 1989: 190-192) [53]. Pilgrims stopping at this volcano would have prayed to explain their purpose. They would bring puha’pah, plants, and stones to this place to leave as an offering. At Toroweap Overlook, people have a clear view of Vulcan’s Anvil and Lava Falls, two important powerful ceremonial features located within the Grand Canyon (see next local landscape description). It is important to note that Toroweap Overlook is the only place where a person can look from the upper rim of the Grand Canyon directly down at the Colorado River. This allows the pilgrim to have a clear view of the powerful places below. The person would be able to talk directly to the Colorado River and draw from its puha. The pilgrim would seek some type of puha from the place, such as a vision, song, or spirit helper. The person could seek more puha to confront new problems facing him or his people. Perhaps the pilgrim would be preparing to go into the canyon for ceremony at Lava Falls.

A small camp would be set up to serve as support for the vision seeker. This location would be near to where the vision seeking would occur but would be sufficiently removed from the location to give the vision seeker privacy. Little is known about vision quest support people except they had two roles: (1) to advise the seeker and help interpret what was happening and (2) to ensure that the vision seeker did not become comatose. The vision was sought over a period of two to three days. When the vision was achieved or at such time that the support person suggested the time to leave had come, they would leave the North Rim area and make their way back to their villages. On the return they would stop at Nampaweap, Little Springs, and Paiute Cave to say exit prayers thanking the spirits for protecting them during their pilgrimage and providing enough puha to withstand the intensity of the vision quest. It was very likely that the returning pilgrims collected puha’pah from Little Springs to bring back to their communities. The puhapah would have been used in curing and blessing ceremonies.

South Pilgrimage Trail: The Grand Canyon Geotrail

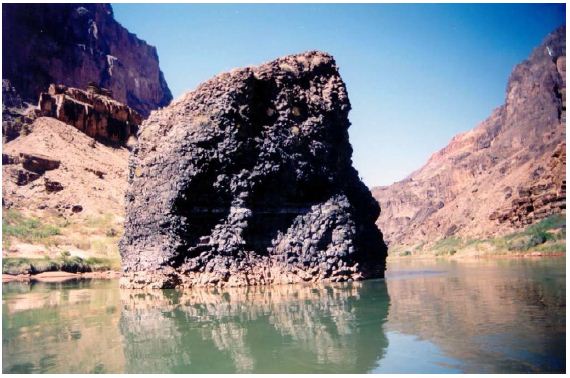

The second portion of the pilgrimage trail is the Grand Canyon Geoscape (Figure 12), which connects geosites on the North Rim with a functionally integrated ceremonial area that is centered on Lava Falls and nearby geosites along the Colorado River downriver from Vulcan’s Anvil. Considered in this analysis are (1) Vulcan’s Anvil, (2) Hot Mineral Spring, (3) Yellow Paint Source Wall, (4) Preparation Rock Shelter, and (5) Lava Falls and Water Babies Peckings Cave. This geoscape is especially critical given it is the location of several volcanic flows deriving from the north, south, and from the walls of the Grand Canyon. These often (apparently 13 times) created dams that filled the Grand Canyon, thus causing the Colorado River to become a massive lake. The remains of some lava flows are visible, and Vulcan’s Anvil is a flat-topped volcanic plug in the middle of the Colorado River. Lava Falls was produced by these lava flows, which formed a truly spectacular volcanic geoscape.

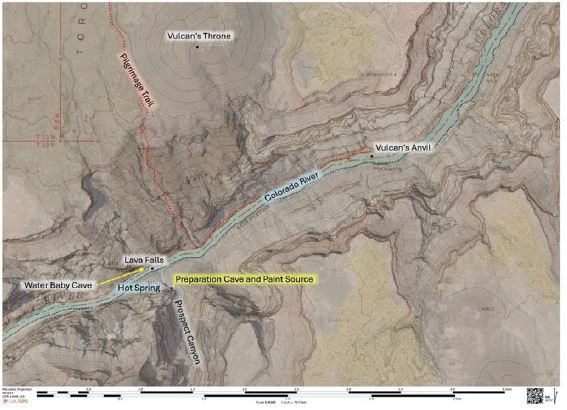

Figure 12: South Pilgrimage Geoscape with Geosites and Geotrail in the Grand Canyon

Vulcan’s Anvil

The Colorado River, as it passes through the Grand Canyon, is a culturally special landscape comprised of many culturally important and interconnected places. The Grand Canyon has always (since Creation) played a critical role in the lives of Southern Paiutes. The canyon and the Colorado River define the boundary of four Southern Paiute sociopolitical districts – Shivwits/Santa Clara, Uinkaret, Kaibab, and the San Juan. Elders identified a network of more than twenty-three trails that permitted free movement across the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River. These allowed Paiutes to have access to many things within the canyon, such as farming, hunting, trade, and ceremony with the Hopis, Havasupai, and Hualapai. This section focuses on a particular local landscape involving places on the North Rim and a series of locations found within the Grand Canyon. This landscape is associated with Paiute doctoring, ceremony, and acquisition of spirit helpers. This landscape is linked to ceremonies discussed in the previous local landscape. This landscape involves steps in preparation for ceremonies at Vulcan’s Anvil near Lava Falls. Vulcan’s Anvil is a powerful doctoring area, which would require long periods of preparation and ceremony before a person or persons could enter this area. The Vulcan’s Anvil-Lava Falls complex was also known as a powerful doctoring site. A well-known Southern Paiute religious leader was associated with this area. Eventually, he moved across the Colorado River and married two Hualapai women, and because of this, he became one of their primary medicine persons. As such, he became an important figure in Hualapai history and a lesson in the meaning of cultural differences in the Grand Canyon region.

Hot Mineral Spring

Pilgrims swam or floated directly across the river to the southern bank of the river where there was and is a hot mineral spring (Figure 13). The spring water is heavily mineralized and was used for prayers and purification. Water was collected at the spring and brought to a nearby ceremonial rock shelter where the pilgrims would have used it as an offering. The spring was cleaned of natural fibers that were either blown out or produced when the Colorado River flooded. Plants, such as willows, were cut back from the spring so pilgrims could use them without interference.

Figure 13: Mineral Springs

Yellow Paint Source Wall

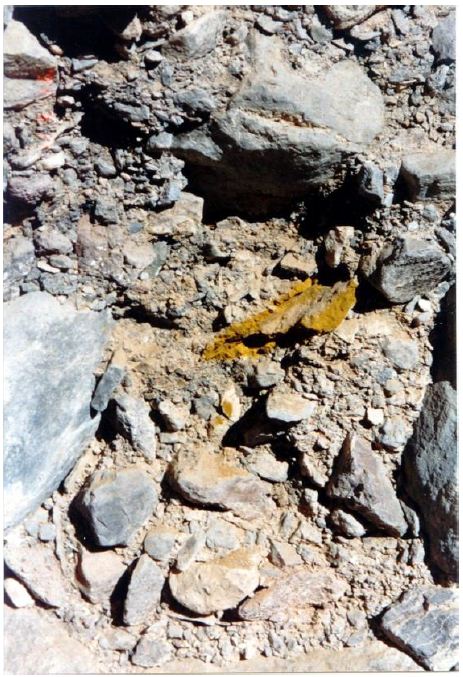

From the spring, pilgrims traveled to a deposit of yellow ochre nodules (Figure 14), which occurs in a vertical gravel wall which is part of the boundary of Prospect Canyon. The yellow ochre deposits in this wall were formed as lava flowed past the wall, which was made of nonvolcanic materials some of which became ochre due to the intense heat and pressure. The Yellow ochre nodules deposit are pure power about the size of a large potato and situated in the wall composed of gravels. The Yellow ochre nodules can be removed easily as a single nodule. When the nodule is broken open it contains almost pure yellow ochre. Yellow ochre, like red ochre, is a powerful element associated with ceremony. The yellow ochre wall is covered in red ochre blessing smudges, which are produced when red paint is dipped with fingers and drawn as lines on the wall.

Figure 14: Yellow Paint Ochre

The yellow ochre was used in medicine and ceremony conducted at Vulcan’s Anvil. To be used in ceremony, the pigment had to be mixed with water to make the yellow paint. To collect the pigment, the pilgrims would have left water from the Hot Mineral Spring as an offering as they collected the pigment. Once the pigment was gathered, the pilgrims ventured to a nearby ceremonial rock shelter where both yellow and red paint figures were painted on the rock walls.

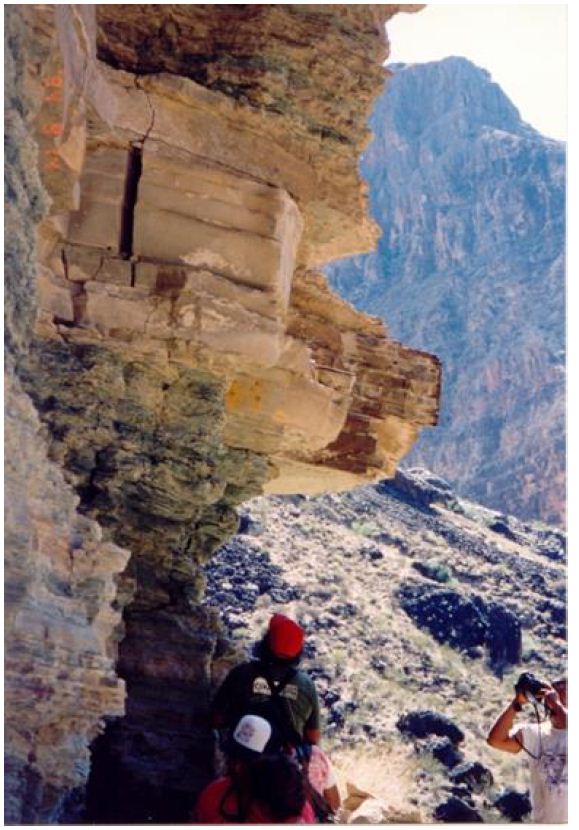

Preparation Rock Shelter

At a ceremonial rock shelter (Figure 15), which is located directly above the yellow paint wall, is where the people continued their preparations for ceremonies at Vulcan’s Anvil and elsewhere like the Water Baby Peckings Cave across the river. The rock shelter contains paint figures made in part from the yellow paint nodules found in the nearby Prospect Canyon wall paint deposits. Inside the rock shelter, the pilgrims would have prayed and prepared themselves. They used the water brought in from the mineral spring. After prayers, the pilgrims would have waited for a spiritual signal to proceed with their journey.

Figure 15: Yellow Paint Rock Shelter

Some Quotes:

- It was a place they went to prepare for something to keep spirits away – that is what we do Images are not a ghost, which would be dots – a drowned person, flat and bloated.

- It is a place where people with supernatural powers came. Women would come here if they needed to be healed by the shaman.

- It may have been a female site – a woman’s isolated site for the moon.

More than half the representatives specifically discussed a connection between the panels and Vulcan’s Anvil. A majority of the representatives perceived the rock art site to be connected to other sites in the area.

People could have received songs during this period to take with them to Vulcan’s Anvil. According to Southern Paiute epistemology, rock shelters are powerful places that people visit to acquire puha and songs that are remembered from earlier times. Once the pilgrims received puha from the rock shelter, and after the appropriate signal, they could continue to visit and climb atop Vulcan’s Anvil. The pilgrim’s support persons would remain at the river’s bank –perhaps in the rock shelter during the pilgrim’s time on Vulcan’s Anvil.

Lava Falls and Water Baby Peckings and Cave

At a place immediately next to Lava Falls the pilgrims would stop to interact with Water Baby peckings located on large lava boulders at the entrance to a small cave. Water babies arespirit helpers for shamans who bring the rain and they are dangerous and powerful. These peckings were on a large boulder in a small cave splashed by water from the churning rapids. The peckings, boulders, and cave occur where the trail crosses the river. The peckings were interpreted as indicating the presence of water babies (Figure 16 and 17).

Figure 16: Lava Falls

Figure 17: Lava Falls Rock Shelter With Water Baby Peckings Inside

Some Quotes

- It was a place where a medicine man or other people came to conduct ceremonies and get their spiritual healing before crossing the river to get the red paint or to visit Vulcan’s Anvil.

- This is where they came to get their spiritual healing and their being able to go across the river and get the paint that they need to protect themselves from the spirits that are bad.

- The majority of people interviewed said that Southern Paiutes visited or used the panel in the One said his family had traditionally visited or used the panel and two said that Southern Paiutes currently visit or use the panel.

- A majority of the representatives said there would be stories or legends associated with the One individual interpreted the panel as reflecting a story or legend about Paiute philosophy.

- A majority of the representatives said the panels would have been used by other Indian people. The Indian people named include the Havasupai, Hopi, Hualapai, and Navajo.

Pilgrims came to this location to say prayers of introduction and to request protection while crossing the river. It is possible that some spiritual leaders came to this spot to receive a water baby as a spirit helper for making rain [54]. The pilgrims drew upon the Puha from the peckings to continue their journey and in return they left offerings of tobacco and Puha’pah for the water babies represented by the peckings.

Vulcan’s Anvil

In order to reach Vulcan’s Anvil, the pilgrims (including medical patients if doctoring was the purpose of the pilgrimage) would have to swim to the center of the Colorado River where Vulcan’s Anvil occurs as a large volcanic plug or throat. Here Vulcan’s Anvil is surrounded by a calm and very deep portion of the Colorado River created in part with the backwater of materials that constitute Lava Falls. Vulcan’s Anvil is the only rock of its kind along the entire Grand Canyon Corridor. Vulcan’s Anvil can best be described as a power rock in a power place thus making it a very special destination for Puha’gants (medicine men) (Figure 18).

Figure 18: Vulcan’s Anvil

When the pilgrim(s) reached Vulcan’s Anvil, they swim from the river’s edge and climb from the water up its vertical slick sides to the wide flat top. On top, a person had a view of the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River up and downstream. Looking up, the pilgrim would view the vertical canyon face containing evidence of a dozen previous volcanic dams and many separate lava flows. Here people could draw from the power of the volcanic rocks, the river, the canyon, and the presence of volcanic plug sitting in the bottom of the river. After a period (up to three days could be needed if medicine healing or if vision quest was involved), the pilgrims would leave the top of Vulcan’s Anvil, swim to the south shore, spend time in the ceremony rock shelter, cleanse themselves in the hot mineral spring, and begin to reverse their journey back to Mount Trumbull. Pilgrims return to the geosites they visited on the path to Vulcan’s Anvil in order to conduct exit prayers and offer expressions of gratitude for safety. Puha’pah was collected by the pilgrims at the base of Lava Falls and the mineral spring to bring back to their villages to be used in curing or other ceremonies. The yellow pigment was carried to be used again in Paiute Cave. There is evidence of the use of this yellow paint at ceremonial sites in Kanab Creek.

Discussion

This is a holistic ethnographic analysis of a long and ancient Native American pilgrimage trail that is situated in a volcanic field composed of cinder cones, lava flows, collapsed lava tubes, and mineral deposits made by lava flows. The area of analysis includes a large volcanic mountain to the north and the Colorado River as it passed through the Grand Canyon. The trail crosses an area of volcanic events where the Grand Canyon was filled with lava thus disrupting the flow of the Colorado River. When these massive dams were formed lakes then extended upriver and along canyons for hundreds of miles. Eventually the dams were eroded away, only to occur again a dozen times. Native people have lived in this area for 40,000 years or more and are documented as actually interacting with lava flows during the past thousand years [51]. In this volcanic landscape or geoscape are unique places or geosites that have special cultural importance to Native American people. Some of these places are culturally organized into the pilgrimage trail or geotrail described and explained in this analysis. The technical prefix – geo – is utilized to describe the trail, places along it, and the broader landscape withing which it occurs. Places along the geotrail are organized and utilized as central component of Native American heritage. The volcanic geology of the area is a primary foundation for Native ceremony. Thus, volcanic events are places critical to Native American heritage [55]. According to Native American Creation accounts volcanos are alive and intended for the benefit of all other (emphasis added) living beings including the wind, rain, animals, plants, and humans. Pilgrims traveled along this trail to perform ceremonies at these locations since Time Immemorial according to Native beliefs. The oldest types of artifacts are regularly found in the area [56,57]. The performance of these ceremonies increases balance between the involved beings, the communities and habitats where they reside, and the Earth itself. For Native Americans, the act of pilgrimage along the geotrail is essential because here they can draw on the most powerful Earth forces and thus can better form relationships between other beings and increase balance in the World [40]. The analysis is intended to explain Native American relationships with what in Western culture and science is call Nature [41]. The reason for participating in the ethnographic studies by tribal governments and their cultural representatives has been and continues to provide an alternative cultural interpretation of the volcanic landscape by which to better inform those people and agencies who manage and use this geoscape. Currently the geoscape is threated by spiritual and physical disruptions deriving from uranium mining, livestock grazing, offroad travel, river raft adventures, and millions of tourist visitors. Native participants in these studies believe (trust) that these actions and their impacts potentially can be mitigated through environmental education using Native American perspectives of the Living Earth. Also essential is Native American ceremonial use of the geotrail, geosites, and geoscape.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the representatives of the USA federal agencies who are both land managers and funders of these ethnographic studies. For the Arizona Strip we thank the Bureau of Land Management Staff especially Gloria Bulletts-Benson. Tribal government support was provided by the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, the Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians, and the San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe. There were six Grand Canyon Colorado River Corridor ethnographic river trips, all of which were supported by the David E. Ruppert for the National Park Service and David Wegner for the Glen Canyon Environmental Studies, the Bureau of Reclamation. Special professional experts included Henry F. Dobyns, Helen C. Fairley, Arthur M Phillips, III, Gilford Harper, Angelita Bulletts and Vivienne C. Jake. Betty Cornelius, Director, Colorado River Indian Tribes supported the participation of the tribal video team. Special thanks to the dozens of tribally appointed cultural representatives who participated. This is their story.

References

- Brocx, M, Semeniuk, V (2017) Towards a Convention on Geological Heritage (CGH) for the protection of Geological Geophysical Research Abstract. 19.

- IUCN WCPA (2024) Geoheritage Specialist Group.

- Brocx M, Semeniuk V (2022) Geoparks, Geotrails, and Geotourism—Linking Geology, Geoheritage, and Geoeducation. Land: An Open Access Journal by MDPI.

- Muzambiq S, Sibarani R, Nasution Z, Gustanto (2024) Geoheritage and cultural heritage overview of the Toba caldera geosite, North Sumatra, Indonesia. Smart Tou 5.

- Moretti R, Moune S, Jessop D, Glynn C, Robert V, et al. (2021) The Basse-Terre Island of Guadeloupe (Eastern Caribbean, France) and Its Volcanic-Hydrothermal Geodiversity: A Case Study of Challenges, Perspectives, and New Paradigms for Resilience and Sustainability on Volcanic Geosciences 11.

- IUGS (2024) https://iugs-geoheritage.org.

- Stoffie RW, Halmo DB, Evans MJ, Austin DE (1994) Piapaxa ‘Uipi (Big River Canyon) Southern Paiute ethnographic resource inventory and assessment for Colorado river corridor, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area Utah and Arizona, and Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Tucson, AZ: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona.

- Stoffie RW, Halmo DB, Evans MJ, Austin DE (1994) Piapaxa ‘Uipi’ (Big River Canyon): Southern Paiute ethnographic resource inventory and assessment for Colorado River Corridor, Tucson, Az: University of Arizona Bureau of Applied Research In Anthropology.

- Sjölander-Lindqvist A, Murin I, Dove ME eds (2022) Anthropological Perspectives on Environmental Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Bennett MR, Bustos D, Pigati, JS, Springer KB, Urban TM, Holliday VT, Reynolds SC, Budka M, Honke JS, Hudson AM, Fenerty B, Connelly C, et (2021) Evidence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. Science. 373: 1528- 1531. [crossref]

- Pigati JS, Springer KB, Honke JS, Wahl D, Champagne MR, et (2023) Independent age estimates resolve the controversy of ancient human footprints at White Sands. Science. 383: 73-74. [crossref]

- Rowe TB, Stafford TW, Fisher DC, Enghild JJ, Quigg JM, et al. (2022) Human Occupation of the North American Colorado Plateau ~37,000 Years Frontiers. Ecology and Evolution. 10.

- Brocx M, Semeniuk V (2007) Geoheritage and geoconservation – History, definition, scope and Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia. 90.

- Osipova E, Shi Y, Kormos C, Shadie P, Zwahlen C, et (2014) IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2014: A conservation assessment of all natural World Heritage sites. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. Pg: 64.

- Ramsey MS (1995) A conflict of water and fire: Remote sensing imagery of the Uinkaret Volcanic Field, Grand Canyon, Arizona. JPL, Summaries of the Fifth Annual JPL Airborne Earth Science Workshop. Volume 2: TIMS Workshop 19-23 (SEE N95- 33789 12-42).

- Powell JW (1873) Exploration of the Colorado River of the West and its tributaries: Explored in 1869, 1870, 1871, and 1872, under the direction of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution, pp. 94-196.

- Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History Global Volcanism Program (2024) Uinkaret Field.

- USGS (2024) Uinkaret Volcanic Field.

- Billingsley GH, Hamblin KW (2001) Geologic Map of Part of the Uinkaret Volcanic Field, Mohave County, Northwestern Arizona: US Geological Survey. Miscellaneous Field Studies MF-2368, scale 1: 31,680, with accompanying 35-page pamphlet.

- Fenton CR, Mark DF, Barfod DN, Niedermann S, Goethals MM, et al. (2013) 40Ar/39Ar dating of the SP and Bar Ten lava flows AZ, USA: Laying the foundation for the SPICE cosmogenic nuclide production-rate calibration project. Quaternary Geochronology. 18: 158-172.

- Hamblin WK (1994) Late Cenozoic Lava Dams in the Western Grand Geological Society of America, Boulder, Colorado, Pg: 1-110.

- Koons ED (1945) Geology of the Uinkaret Plateau, Northern Arizona. Geological Society of America 56: 151-180.

- Maxon JH (1950) Lava Flows in the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River, Geological Society of America Bulletin. 61: 9-15.

- Rappaport RA (1999) Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Liljeblad S (1986) Oral Tradition: Content and Style of Verbal In: Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 11, Great Basin. Warren L. d’Azevedo, ed., Pg ; 641-659. Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

- Miller J (1983) Basin Religion and Theology: A Comparative Study of Power (Puha) Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. 5.

- Stoffie RW, Zedeño MN, Halmo DB, (eds) (2001) American Indians and the Nevada test site: a model of research and consultation. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- Bean LJ (1976) Power and Its Applications in Native California. In Native Californians: A Theoretical Retrospective. J. Bean and T.C. Blackburn, eds. Pg: 407-20. Ramona, CA: Ballena Press.

- Blackburn T (1974) December’s Child: A Book of Chumash Oral Narratives. University of California, Los Angeles.

- Fowler C (1992) In the Shadow of Fox Peak: An Ethnography of the Cattail-Eater Northern Paiute People of Stillwater Marsh. Cultural Resource Series 5. Fallon: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service Region 1, Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge.

- Stoffie RW, Chmara-Huff FP, Van Vlack KA, Toupal RS (2004b) Puha Flows from It: The Cultural Landscape Study of the Spring Mountains. Tucson: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona.

- Dellenbaugh FS (1926) A Canyon Voyage: The Narrative of the Second Powell Expedition Down the Green-Colorado River from Wyoming, and the Explorations on Land, in the Years 1871 and Yale University Press. 2nd Edition.

- Carroll AK, Zedeño MN, Stoffie RW (2004) Landscapes of the Ghost Dance: A Cartography of Numic Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 11.

- Stoffie RW, Van Vlack K, Carroll AK, Chmara-Huff F, Martinez A (2005) Volume One Of The Arizona Strip Landscapes and Place Name Study. Tucson, AZ, USA: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona.

- Carroll A, Stoffie R, Van Vlack K, Arnold R, Toupal R, Fauland H, Haverland A (2006) Black Mountain: Traditional Use of a Volcanic Landscape. Report prepared for Nellis Air Force Base—Air Command Nevada Test and Training Range Native American Interaction Program. Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson.

- Stoffie RW, Carroll AK, Eisenberg A (2000a) Ethnographic Assessment of Kaibab Paiute Cultural Resources in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah. Tucson, AZ: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology (BARA), University of Arizona.

- Carroll AK, Stoffie, R (2005) Ghost Dance Movement. In American Indian Religious Traditions An Encyclopedia (Volume 1, Pg: 337-344) Suzanne Crawford and Dennis F. Kelley editors. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO Books.

- Stoffie R, Arnold R, Van Vlack K, O’Meara S, Medwied-Savage J (2009) Black Mountain: Traditional Uses of a Volcanic Landscape, Vol. 2. Report prepared for Nellis Air Force Base—Air Command Nevada Test and Training Range Native American Interaction Program. Tucson, AZ: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson.

- Toupal R, Stoffie R (2004) Traditional Resource Use of the Flagstaff Area Tucson, Arizona: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona.

- Van Vlack K (2012a) Puaxant Tuvip: Powerlands Southern Paiute Cultural Landscapes and Pilgrimage Trails, [PhD Dissertation]. [Tucson, AZ]: University of Arizona.

- Van Vlack, A. (2012b) Southern Paiute Pilgrimage and Relationship Formation. Journal of Ethnology 51(2): 129-140.

- Van Vlack K, Stoffie R, Pickering E, Brooks K, Delfs J (2013) Unav-Nuquaint: Little Springs Lava Flow Ethnographic Investigatio Report prepared for the National Park Service and Bureau of Land Management. Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson.

- Stoffie RW, Austin DE, Fulfrost BK, Phillips AM, Drye TF, (1995a) Itus, Auv, Te’ek (past, present, future): managing Southern Paiute resources in the Colorado River corridor. Tucson, AZ: Southern Paiute Consortium; Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology University of Arizona.

- Stoffie RW, Austin DE, Halmo DB, Phillips AM (1995b) Ethnographic Overview and Assessment: Zion National Park, Utah, and Pipe Spring National Monument, Pp. 320. Tucson, AZ; Pipe Spring, AZ: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona and The Southern Paiute Consortium.

- Stoffie RW, Loendorf L, Austin DE, Halmo DB, Bulletts A(2000b) Ghost Dancing the Grand Canyon: Southern Paiute Rock Art, Ceremony, and Cultural Current Anthropology 41: 11-38. [crossref]

- Stoffie R (1979) Interview with Dan Bullets.

- Stoffie RW, Dobyns HF (1982) Puaxant Tuvip: Utah Indians Comment on the Intermountain Power Project, Section of Intermountain Adelanto Bipole 1 Proposal. Kenosha, WI: University of Wisconsin- Parkside, Applied Urban Field School.

- Fowler DD, Fowler CS, eds (1971) Anthropology of the Numa: John Wesley Powell’s Manuscripts on the Numic Peoples of Western North America 1868-1880. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Kelly, IT (1971) Southern Paiute ethnography. New York: Johnson Reprint Corp.

- Stoffie RW, Austin DE, Halmo DB, Phillips AM (1997a) Ethnographic Overview and Assessment: Zion National Park, Utah and Pipe Spring National Monument, Arizona. Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona. Tucson, AZ.

- Van Vlack K (2022) Dancing With In Sjölander-Lindqvist, A., Murin I., Dove M.E. eds. Anthropological Perspectives on Environmental Communication. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Elson MD, Ort MH, Hesse SH, Duffield WA (2002) Lava, Corn, and Ritual in the Northern Southwest. American Antiquity. 67: 119-135.

- Hamblin, KW (1989) Pleistocene Volcanic Rocks of the Western Grand Canyon, In Geology of Grand Canyon, Northern Arizona. D.P. Elston, G.H. Billingsley, and R.A. Young, (eds.) Washington, D.C.: American Geophysical Union.

- Stoffie R, Toupal R, Zedeño M (2002) East of Nellis: Cultural Landscapes of the Sheep and Pahranagat Mountain Ranges: An Ethnographic Assessment of American Indian Places and Resources in the Desert National Wildlife Range and the Pahranagat National Wildlife Refuge of Nevada. Report prepared for Science Applications International Corporation and Nellis Air Force Base and Range Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson.

- Van Vlack KA (2018) The Journey to Kavaicuwac. The International Journal of Intangible Heritage 13: 129-141.

- Ruuska Alex K (2023) When The Earth Was New: Memory, Materiality, and the Numic Ritual Cycle. Pre-print Version. University of Arizona Campus Repository. March 14, 2023.

- Stoffie RW, Loendorf LL, Austin DE, Halmo, Bulletts DB, et al.(1995) Tumpituxwinap (Storied Rocks): Southern Paiute Rock Art in the Colorado River Corridor. Tucson, AZ: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona.