Abstract

Objective: In recent years, the rate of nurses changing jobs has continued to exceed that of new graduates entering the workforce. Kato (2019) identified happiness as an individual-level factor accounting for this trend, but the happiness nurses derive from their work has not been fully examined. Therefore, this study examined the constructs and factor structure of the sense of job happiness of nurses.

Methods: A self-administered questionnaire was administered to 1099 nurses working in 28 facilities. The study period was from October 2021 to January 2022. The survey included 109 items on the perception of job happiness of nurses (Tanaka & Fuse, 2022), and an exploratory factor analysis was conducted.

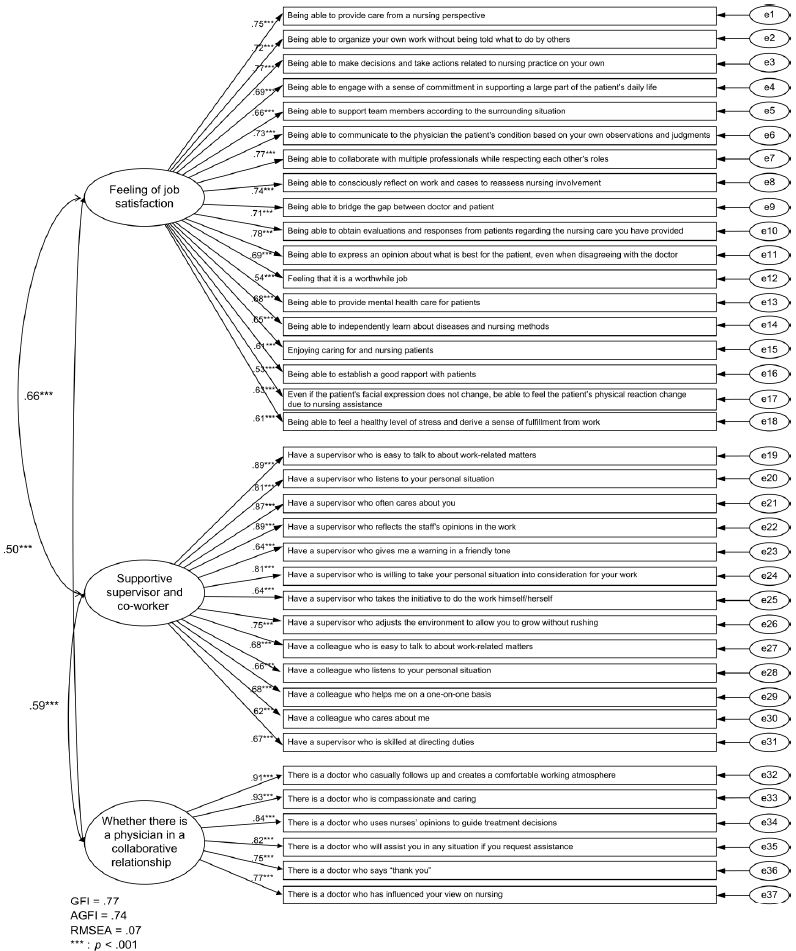

Results: The number of valid responses was 486 (valid response rate: 77.0%). A main factor analysis with Promax rotation was conducted, and three factors with 37 items were extracted. The first factor consisted of 18 items and was named feeling of job satisfaction (α=0.94). The second factor consisted of 13 items and was named supportive supervisor and coworker (α=0.94). The third factor consisted of six items and was named whether there is a physician in a collaborative relationship (α=0.92).

Conclusion: The results suggest that the perception of job happiness of nurses is shaped by three aspects: feeling of job satisfaction, supportive supervisor and coworker, and whether there is a physician in a collaborative relationship.

Keywords

Nurse, Turnover, Happiness

Introduction

The nursing industry is characterized by a high turnover of personnel because it is easier than in other industries for people to leave and re-enter the workforce. In recent years, the rate of nurses changing jobs has continued to exceed that of new graduates entering the workforce, and further promotion of the acceptance of people changing jobs or re-entering the workforce is required to secure human resources (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2018) [1]. Previous studies on job change have examined the factors that increase individual job satisfaction and their causal relationships to retain personnel, and have sought to improve factors on the organizational side that decrease job satisfaction. However, when looking at the relationship between job satisfaction and intention to change jobs, it is evident that a high level of job satisfaction does not necessarily encourage retention. According to a previous study, people sometimes change jobs even when they are highly satisfied with their professional status [2]. Teramoto [3] reported that more than half of the nurses surveyed felt a sense of satisfaction and fulfillment in their work, yet more than 80% of them wanted to change jobs. These results suggest that a high level of commitment to the nursing profession and satisfaction with daily tasks are not sufficient to predict or evaluate the likelihood of retention in an organization. Tanaka and Fuse [4] focused on nurses who repeatedly change jobs while showing satisfaction and high commitment to their workplace. They showed that these nurses were motivated by personal factors and changed jobs to fulfill self-actualization values. They further stated that individual factors matter more than organizational factors, as previously indicated, and pointed out the need for research that considers individual factors. Kato [5] identified happiness as one of the personal factors that encourage people to stay in the same workplace. According to Seligman [6], a pioneer of positive psychology, happiness can be categorized into three measurable elements, namely “enjoyment,” “being engaged,” and “finding meaning,” and pursuing only one of these elements will not produce happiness. In other words, happiness is a concept that encompasses satisfaction, and we believe that it is necessary to incorporate the perspective of happiness in one’s professional life to comprehensively examine the retention of human resources in the study of job change. To facilitate research on happiness, the WHO developed a self-assessment questionnaire (Subjective Well-Being Inventory), which is mainly used in the field of psychiatry to measure the degree of fatigue. Therefore, a psychological well-being scale was developed by Nishida (2000) [7] to measure the mental health of nurses. This scale assesses overall well-being in life and consists of six dimensions: “personal growth,” “purpose in life,” “autonomy,” “self-acceptance,” “ability to control environment,” and “positive relationships with others.” However, a construct validity problem has been pointed out in that there are factors that belong to neither psychological wellbeing nor subjective happiness [8]. In the area of nursing, the happiness that nurses experience in their work has not been sufficiently examined. Studies related to job change have focused on the relationship with job satisfaction and organizational commitment, and we found no studies that examined the relationship between individual nurses’ happiness and their intention to change jobs. We believe that it would be useful for retention management to clarify the concepts that constitute nurses’ happiness and to examine the relationship of this variable with nurses’ intention to change jobs.

Objective

We extracted the constructs of the sense of job happiness of nurses working in hospitals and examined the factor structure model.

Operational Definitions of Terms

Job change: Many nurses start working for another medical institution within five years after leaving their jobs (Japan Medical Association, 2008) [9]. Therefore, a job change for a nurse is like a transfer to a new company by changing only the place of work, regardless of the length of time until the nurse is reemployed. Accordingly, in this study, a job change is defined as “a transfer to another organization as a nursing professional, regardless of the period of unemployment.” Happiness: In this study, happiness is defined as “enjoyment, being engaged, and finding meaning” based on the definition by Martin Seligman, the pioneer of positive psychology.

Methods

Surveyed Facilities

A simple random sampling method was used to select 184 facilities from hospitals with at least 20 beds nationwide. Among these, consent was obtained from 28 facilities (14.7%), which were selected for the survey.

Participants

The study sample consisted of 1099 nurses working in hospitals with 20 or more beds throughout Japan who provided their consent to participate in the study. The survey method was a self-administered questionnaire by mail. We asked the representatives of the nursing departments of the facilities that had provided their consent to cooperate in the study to specify the number of nurses to be included in the study and sent a survey request for the number of participants, a survey form, and a return envelope to the representatives. The questionnaires were collected at the participants’ discretion using the enclosed return envelope. Individual nurses’ consent to cooperate in the study was confirmed if the consent box on the cover page of the survey form was marked when returned.

Survey Period

The survey period was from October 2021 to March 2022.

Survey Items

Attributes of Participants

The questionnaire included questions on gender, age, years of experience as a nurse, years of experience, position, assigned patient care area and work pattern at the current hospital, highest level of education in nursing, number of job changes as a nurse, whether having a spouse, whether having a child, whether providing a family member nursing care, household income in the last 12 months, and the level of happiness.

Design of a Questionnaire on the Sense of Job Happiness of Nurses

Tanaka and Fuse (2022) [10] examined items on the perception of job happiness of nurses by using a quantitative analysis method with a quantification on qualitative data, using the text mining software KH Coder developed by Higuchi et al. In total, 351 statements regarding happiness were extracted and categorized into 10 variables: salary, professional status, nursing management, nurses’ relationship with each other, doctor–nurse relationship, patient–nurse relationship, professional autonomy, nursing work, work–life balance, and self-actualization. A hierarchical cluster analysis was performed, and from each cluster 109 important sentences that reflect the concept of the cluster were extracted. These 109 statements were selected as the items for our survey. The participants were asked to rate on a five-point scale how important the 109 items were for their own happiness: “Not important at all” (1 point), “Somewhat unimportant” (2 points), “Neither important nor unimportant” (3 points), “Somewhat important” (4 points), and “Very important” (5 points).

Analysis Methods

The statistical software SPSS (version 22 for Windows) and AMOS (version 22) were used to conduct the analyses.

Analysis of Question Items

All questions were tabulated to calculate frequencies and percentages, as well as means and standard deviations. The test was two-tailed, and p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Happiness Assessment

The Cantril ladder scale (Cantril, 1965) [11], which assesses cognitive judgments about the extent to which respondents currently feel happiness, was used for the happiness assessment. This scale requires respondents to reflect on their lives to date and make deliberate judgments, and has been widely used since its development. The respondents were asked to provide ratings on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 0 being the most unhappy and 10 being the most happy.

Factor Analysis

Selection of Question Items

We examined the ceiling/floor effect of the responses to the 109 items on the perception of job happiness of nurses.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

An exploratory factor analysis was conducted using a main factor analysis with Promax rotation to ascertain the factor structure of the perception of job happiness of nurses. A G-P analysis was conducted to examine the reliability of the questionnaire items. To examine internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the questions of the extracted factors were calculated.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

A covariance structure analysis was performed as a confirmatory factor analysis. The chi-square value, GFI (Goodness of Index), AGFI (Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), and RMSEA (Root Mean Square of Approximation) were used as fit indexes for the factor structure. The factor structure was partially evaluated with the test statistic, and the criterion was that the absolute value of the test statistic should meet or exceed 1.96, p < .05 [12].

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted with the approval of the Ethical Review Committee of the organization that the researchers belong to. The following were explained in writing to the representative of the nursing department of each surveyed facility and to the participants of the survey: the purpose of the study, the method, the time required, that participation in the study is voluntary and that the participants will not be disadvantaged if they decline, that the responses are anonymous, that the data obtained will be processed statistically and that it will not be possible to identify individuals, that the responses will not be used for any purpose other than this survey, whether or not the respondents provide their consent to participate in the survey and their responses will not affect any individual or the institution to which the individual belongs, that it will be determined that consent has been obtained if the consent box on the cover page of the survey form was marked when returned, and that there are no conflicts of interest related to this research. The survey form and return envelope did not include the names of the participants or the names of institutions, and were strictly sealed and addressed to the researcher for return. The questionnaires and electronic media containing the recorded data were kept locked until the study was completed to protect personal information.

Results

The survey forms were distributed to 1099 nurses, and 631 were returned (57.4% response rate). Data from 145 respondents with inappropriate or missing answers on the survey form were excluded. As a result of the above process, the number of valid responses was 486 (valid response rate: 77.0%).

Attributes of the Participants

There were 433 female (89.1%) and 53 male (10.9%) participants. The mean age was 41.1 ± 10.9 years, and the mean years of nursing experience was 18.1 ± 10.5 years. As for the means of the other variables, 303 (62.3%) had a spouse, 258 (53.1%) had at least one child, and 131 (27.0%) had household incomes between 3 and 5 million yen, and the level of happiness was moderate, being 5.7 ± 1.7 (Table 1).

Table 1

|

n = 486 |

||||

|

n |

(%) |

|||

| Gender | Female |

433 |

(89.1) |

|

| a | Male |

53 |

(10.9) |

|

| Age | Mean ± standard deviation |

41.1 ± 10.9 |

||

| Years of experience as a nurse | Mean ± standard deviation |

18.1 ± 10.5 |

||

| Years of experience at the current hospital | Mean ± standard deviation |

12.3 ± 9.9 |

||

| Position at the current hospital | Staff |

319 |

(65.6) |

|

| Assistant chief nurse |

7 |

(1.4) |

||

| Chief nurse |

66 |

(13.6) |

||

| Vice nurse manager |

42 |

(8.6) |

||

| Nurse manager |

38 |

(7.8) |

||

| Other |

13 |

(2.7) |

||

| N/A |

1 |

(0.2) |

||

| Assigned patient care area at the current hospital | Ward |

357 |

(73.5) |

|

| Outpatient |

49 |

(10.1) |

||

| ICU |

6 |

(1.2) |

||

| ER |

8 |

(1.6) |

||

| Operating room |

24 |

(4.9) |

||

| Home-based care |

6 |

(1.2) |

||

| Other |

36 |

(7.4) |

||

| Work pattern at the current hospital | Three-shift system |

148 |

(30.5) |

|

| Two-shift system |

195 |

(40.1) |

||

| Day shift only |

77 |

(15.8) |

||

| Night shift/ evening shift |

1 |

(0.2) |

||

| Other |

64 |

(13.2) |

||

| N/A |

1 |

(0.2) |

||

| Highest level of education in nursing | High school, nursing major |

40 |

(8.2) |

|

| Two-year program for nurses (Training school/college) |

84 |

(17.3) |

||

| Training school for nurses, three-year program |

265 |

(54.5) |

||

| Nursing college, three-year program |

24 |

(4.9) |

||

| Nursing university |

34 |

(7.0) |

||

| Public health nurse/midwifery school |

17 |

(3.5) |

||

| Graduate school of nursing |

5 |

(1.0) |

||

| Other |

15 |

(3.1) |

||

| N/A |

2 |

(0.4) |

||

| Number of job changes as a nurse | Mean ± standard deviation |

1.2 ± 1.6 |

||

| Whether having a spouse | Yes |

303 |

(62.3) |

|

| No |

182 |

(37.4) |

||

| N/A |

1 |

(0.2) |

||

| Whether having a child | Yes |

258 |

(53.1) |

|

| No |

228 |

(46.9) |

||

| Whether providing a family member nursing care | Yes |

33 |

(6.8) |

|

| No |

451 |

(92.8) |

||

| N/A |

2 |

(0.4) |

||

| Household income | Under 3 million yen |

41 |

(8.4) |

|

| 3 million to under 5 million yen |

131 |

(27.0) |

||

| 5 million to under 7 million yen |

121 |

(24.9) |

||

| 7 million to under 10 million yen |

125 |

(25.7) |

||

| 10 million yen or more |

57 |

(11.7) |

||

| N/A |

11 |

(2.3) |

||

| The level of happiness | Mean ± standard deviation |

5.7 ± 1.7 |

||

Factor Structure of Job Happiness of Nurses Working in Hospitals

Exploratory Factor Analysis

To clarify the factor structure of the sense of job happiness of nurses, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted on 109 questions using a main factor analysis with Promax rotation. First, we calculated the means and standard deviations of 109 items on the sense of job happiness of nurses and checked the distribution of scores. Sixteen items with ceiling or floor effects were excluded from the analysis. Next, a main factor analysis with Promax rotation was conducted for the remaining 93 items. The number of factors was determined by referring to the scree plot and the decay of eigenvalues in the initial solution, and 3 factors were extracted. Three factors were assumed, and items that showed factor loadings of below .40 and two or more factors of .40 or higher were excluded from the analysis. Finally, three factors were extracted consisting of 37 items with factor loadings of .40 or higher for only one factor. The final factor patterns and inter-factor correlation after Promax rotation are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

|

n = 486 |

|||

|

Factor 1 |

Factor 2 |

Factor 3 |

|

| Factor 1: Feeling of job satisfaction | |||

| Being able to provide care from a nursing perspective |

0.75 |

-0.10 |

.07 |

| Being able to organize your own work without being told what to do by others |

0.72 |

-0.06 |

-0.04 |

| Being able to make decisions and take actions related to nursing practice on your own |

0.71 |

-0.04 |

-0.01 |

| Being able to engage with a sense of commitment in supporting a large part of the patient’s daily life |

0.71 |

-0.04 |

0.09 |

| Being able to support team members according to the surrounding situation |

0.70 |

-0.02 |

0.06 |

| Being able to communicate to the physician the patient’s condition based on your own observations and judgments |

0.70 |

-0.02 |

0.12 |

| Being able to collaborate with multiple professionals while respecting each other’s roles |

0.69 |

-0.03 |

0.13 |

| Being able to consciously reflect on work and cases to reassess nursing involvement |

0.69 |

-0.07 |

0.13 |

| Being able to bridge the gap between doctor and patient |

0.68 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

| Being able to obtain evaluations and responses from patients regarding the nursing care you have provided |

0.66 |

0.12 |

0.06 |

| Being able to express an opinion about what is best for the patient, even when disagreeing with the doctor |

0.66 |

-0.10 |

0.18 |

| Feeling that it is a worthwhile job |

0.66 |

.13 |

-0.27 |

| Being able to provide mental health care for patients |

0.55 |

.08 |

0.14 |

| Being able to independently learn about diseases and nursing methods |

0.55 |

-0.03 |

0.18 |

| Enjoying caring for and nursing patients |

0.55 |

-0.09 |

0.12 |

| Being able to establish a good rapport with patients |

0.54 |

-0.05 |

0.30 |

| Even if the patient’s facial expression does not change, be able to feel the patient’s physical reaction change due to nursing assistance |

0.52 |

-0.02 |

0.26 |

| Being able to feel a healthy level of stress and derive a sense of fulfillment from work |

0.51 |

.10 |

0.07 |

| Factor 2: Supportive supervisor and co-worker | |||

| Have a supervisor who is easy to talk to about work-related matters |

-0.05 |

0.86 |

0.08 |

| Have a supervisor who listens to your personal situation |

0.01 |

0.85 |

-0.08 |

| Have a supervisor who often cares about you |

-0.02 |

0.84 |

0.04 |

| Have a supervisor who reflects the staff’s opinions in the work |

-0.01 |

0.80 |

0.03 |

| Have a supervisor who gives me a warning in a friendly tone |

-0.19 |

0.77 |

0.01 |

| Have a supervisor who is willing to take your personal situation into consideration for your work |

0.01 |

0.70 |

0.14 |

| Have a supervisor who takes the initiative to do the work himself/herself |

-0.08 |

0.70 |

0.01 |

| Have a supervisor who adjusts the environment to allow you to grow without rushing |

0.03 |

0.64 |

0.17 |

| Have a colleague who is easy to talk to about work-related matters |

0.09 |

0.60 |

0.06 |

| Have a colleague who listens to your personal situation |

0.10 |

0.58 |

0.04 |

| Have a colleague who helps me on a one-on-one basis |

0.15 |

0.58 |

0.02 |

| Have a colleague who cares about me |

0.11 |

0.58 |

-0.02 |

| Have a supervisor who is skilled at directing duties |

0.03 |

0.53 |

0.19 |

| Factor 3: Whether there is a physician in a collaborative relationship | |||

| There is a doctor who casually follows up and creates a comfortable working atmosphere |

-0.01 |

0.07 |

0.81 |

| There is a doctor who is compassionate and caring |

-0.01 |

0.09 |

0.80 |

| There is a doctor who uses nurses’ opinions to guide treatment decisions |

0.04 |

0.09 |

0.76 |

| There is a doctor who will assist you in any situation if you request assistance |

-0.02 |

0.14 |

0.72 |

| There is a doctor who says “thank you” |

0.01 |

0.05 |

0.70 |

| There is a doctor who has influenced your view on nursing |

0.10 |

0.10 |

0.64 |

| Factor correlation matrix Factor 1 |

1.00 |

0.62** |

0.41** |

| Factor 2 |

1.00 |

.51** |

|

| Factor 3 |

1.00 |

||

| Reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s α) |

0.94 |

0.94 |

0.91 |

| Factor extraction method: Main factor analysis, Rotation method: Promax rotation | |||

| The percentage of the total variance of the 37 items explained by the three factors before rotation is 51.06% | |||

| KMO sample validity: 0.90 | |||

| *:p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 | |||

The percentage of the total variance of 37 items explained by the three factors before rotation was 51.06%. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy, which indicates factor validity, was .90. A G-P analysis was conducted to examine the reliability of the questionnaire items. The results showed that the mean scores for the top 25% of the 37 items were significantly higher than those for the bottom 25% (p=0.00). Therefore, we determined that sufficient reliability was obtained.

Factor Naming

The first factor consisted of 18 items, including “be able to provide care from a nursing perspective,” “be able to organize your own work without being told what to do by others,” and “be able to make decisions and take actions related to nursing practice on your own.” These items showed high loadings on attitudes and behaviors toward working autonomously, positive self-evaluation of work, and being able to feel fulfilled. Therefore, we named the factor feeling of job satisfaction based on the semantic content of each item. The second factor consisted of 13 items, including “have a supervisor who is easy to talk to about work-related matters,” “have a supervisor who listens to your personal situation,” and “have a supervisor who often cares about you.” These items showed high loadings on the content of seeking direct and indirect extra care from supervisors and peers and being a supportive presence physically, mentally, and emotionally in their workplace. Therefore, based on the semantic content of each item, we named the factor supportive supervisors and coworker. The third factor consisted of six items, including “there is a doctor who casually follows up and creates a comfortable working atmosphere,” “there is a doctor who is compassionate and caring,” and “there is a doctor who uses nurses’ opinions to guide treatment decisions.” These items showed high loadings on the content that required physicians and nurses to collaborate in caring for the patient and have a mutually respectful relationship. Therefore, based on the semantic content of each item, we named it whether there is a physician in a collaborative relationship. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each factor were α=0.94 for feeling of job satisfaction, α=0.94 for supportive supervisor and coworker, and α=0.91 for whether there is a physician in a collaborative relationship, confirming a high degree of internal consistency.

Examination of Construct Validity

In the primary survey, the perception of job happiness of nurses was investigated by means of an open-ended questionnaire and interviews, and the questions were developed by content analysis. We compared the items falling into the 10 categories extracted when developing the questionnaire (Tanaka & Fuse, 2022) [10] with the items in the three factors extracted by the exploratory factor analysis. The results showed that feeling of job satisfaction corresponded to the concepts of “professional autonomy,” “nursing work,” “self-actualization,” and “patient–nurse relationship”; supportive supervisors and coworker to “nursing management” and “mutual influence among nurses”; and whether there is a physician in a collaborative relationship to “doctor–nurse relationship.” To examine construct validity, a covariance structure analysis was conducted as a confirmatory factor analysis. The three factors extracted in the exploratory factor analysis were used as latent variables, and the analysis was conducted assuming that there was a correlation among the three factors based on the results of the inter-factor correlation. The resulting fit index was χ2=2475.30, p=0.00. The χ-square value has the tendency of being rejected as the number of samples increases. After checking other fit indices, GFI=0.77, AGFI=0.74, and RMSEA=0.07, which met statistically acceptable levels, we concluded that construct validity was confirmed. The test statistic was 1.96 or higher for all items (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Results of a covariance structure analysis of the sense of job happiness of nurses

Discussion

Evaluation of the Reliability and Validity of the Factor Structure Model

In evaluating content validity, the primary survey was conducted, supervised by an expert panel to determine whether it captured the perception of job happiness of nurses, and the questionnaire was developed and modified. This ensured content validity. Construct validity determines whether the scale is actually measuring the construct that it is assumed to be measuring. Comparing the three factors extracted by the exploratory factor analysis with the 10 categories extracted when the questionnaire was developed, the results showed a decrease in the number of items, but the categories consisted of almost similar items. The percentage explaining the total variance of the 37 items of the three factors before rotation was 51.06%; this indicates that the three factors measure the level of happiness that nurses feel in the workplace. To examine the internal consistency reliability of the three factors, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated: α=0.94 for feeling of job satisfaction, α=0.94 for supportive supervisor and coworker, α=0.91 for whether there is a physician in a collaborative relationship. Since Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is considered to indicate high internal consistency if it is greater than 0.7 [13], the reliability of each factor in this study is considered high. In the covariance structure analysis, the fit indices were GFI=0.77, AGFI=0.74, and RMSEA=0.07. The closer the values of GFI and AGFI are to 1, the better the fit to the data, and models with significantly lower AGFI compared to GFI are not preferred [14]. Based on the overall evaluation of the fit indices, we believe that the validity of the 37 items of the three factors has been verified. Based on the above, it was concluded that the factor structure model of happiness among nurses working in hospitals was reliable and valid.

Three Factor Characteristics of Job Happiness of Nurses Working in Hospitals

The first factor feeling of job satisfaction consisted of items such as “be able to provide care from a nursing perspective,” “be able to organize your own work without being told what to do by others,” and “be able to make decisions and take actions related to nursing practice on your own.” Ryan and Deci (2000) [15] stated that the desire to choose one’s own actions in life must be satisfied in order to be reflected in the performance of one’s work duties. Feeling of job satisfaction includes gaining high self-esteem and confidence in performing their duties while proactively gaining experience as a nurse and finding satisfaction in their own nursing method through providing care, regardless of their patient’s awareness. These findings suggest that nurses perceive happiness as an internal reward based on their own approach to and evaluation of nursing. The second factor, supportive supervisor and coworker, consisted of items such as “have a supervisor who is easy to talk to about work-related matters,” “have a supervisor who listens to your personal situation,” and “have a supervisor who often cares about you.” Social relationships are particularly powerful enhancers of happiness [16] and it has been reported that happiness is amplified when an individual’s desire to maintain close and stable relationships in social settings is satisfied [15]. The factor supportive supervisor and coworker focuses on the most familiar relationships in the work environment, particularly supervisors and coworkers, and includes a desire for these relationships to be a source of support for the individual nurse and a place where tolerance and passivity are acceptable. This suggests that nurses perceive happiness from an adaptive aspect, passively accepting the support of others in their workplace relationships. The third factor, whether there is a physician in a collaborative relationship, consisted of items such as “there is a doctor who casually follows up and creates a comfortable working atmosphere,” “there is a doctor who is compassionate and caring,” and “there is a doctor who uses nurses’ opinions to guide treatment decisions.” Yoshii (2003) examined the collaboration between physicians and nurses through a literature review of nursing research in Europe and the United States, and found that it is necessary to respect the opinions and concerns of both their own profession and those of the other profession in establishing an equal power relationship. Kusakari et al. [17] stated that the relationship and collaboration between physicians and nurses directly relates to the job satisfaction of nurses, suggesting that a collaborative physician is a key person for nurses. The factor whether there is a physician in a collaborative relationship includes nurses’ hope that they are not subordinate to the physician, but rather influence the physician’s decision-making, and that a collegial relationship is achieved. These findings suggest that nurses perceive happiness in terms of aspects related to the formation of relationships with physicians.

Significance and Potential Use of Factor Structure Models

Nurses who are satisfied with the organization they are currently employed by but have a high intention to change jobs prioritize the acquisition of a sense of well-being in their professional life and are willing to change jobs in pursuit of self-fulfillment [15]. Therefore, it is meaningful to examine the sense of job happiness of nurses in considering future interventions to support nurses’ retention in the organization. In this study, a questionnaire was developed using a combination of interviews and open-ended questionnaire surveys to analyze the sense of job happiness of nurses. We believe that this finding is useful in understanding the relationship between individual nurses’ level of happiness in their work and their intention to change jobs. In addition, it may be possible to identify the characteristics of happy nurses that lead to retention by analyzing the relationship between the three factors constituting happiness and personal attributes, intention to change jobs, and level of happiness. Furthermore, this study is expected to clarify assessment items to support retention management and to guide the examination and development of effective measures to support nurse retention.

Limitations of This Study

In this study, we clarified the factor structure of the sense of job happiness of nurses and elucidated the characteristics of their happiness. As this study was a cross-sectional analysis only, it was not possible to estimate the effects of job changes and other life events on happiness. Future studies are needed to examine changes in the levels of happiness over the course of one’s career and life, using follow-up surveys.

Conclusion

- The mean age of the nurses was 41.1 ± 10.9 years, the mean years of nursing experience was 18.1 ± 10.5 years, and the mean level of well-being was 5.7 ± 1.7.

- An exploratory factor analysis revealed that the sense of job happiness of nurses consisted of 18 items (α=0.94) for feeling of job satisfaction, 13 items (α=0.94) for supportive supervisor and coworker, and six items (α=0.91) for whether there is a physician in a collaborative relationship, resulting in a total of 37 items comprising three factors.

- A confirmatory factor analysis showed that the factor structure fit index of the sense of job happiness of nurses was GFI=0.77, AGFI=0.74, and RMSEA=0.07, indicating the validity of the factor structure.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the nurses who participated in this study.

References

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2018) Nenrei ni kakawari nai tensyoku saishusyoku-sya no ukeire sokusin no tame no sisin [Guidelines for promoting the acceptance of people changing jobs or re-entering the workforce regardless of age].

- Sawada T, Hatano H, Sakai J. (2002) Zyosei kangosi no syokumu manzoku to sono eikyou insi. Kyoubunsankouzoubunseki wo motiita inga moderu no kensyo [Job satisfaction of female nurses and its influencing factors: A causal model using covariance structure analysis]. Bulletin of Ehime College of Health Science 15: 1-9.

- Teramoto K, Kita I, Yamaoka K (2006) Tyuken kangosi no risyoku genin wo tyousa suru. Tyuken kangosi no teityaku-ritu wo takameru tame ni [The causes of job turnover of mid-career nurses: to increase the retention rate]. Proceedings of the Japanese Nursing Association, Nursing Management, 37.

- Tanaka S, Fuse J (2019) Keikaku-teki kodo riron ni motodzuku kangoshi no tenshoku ishi kettei moderu no kochiku [Development of a Decision-Making Model of Job Change in Nurses Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior]. Journal of International Nursing Research 42: 787-802.

- Kato T (2019) Naze anata bakari turai me ni au noka? [Why do only you have a hard time?]. Asahi Shimbun Publishing.

- Seligman ME (2004) Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Simon and Schuster.

- Nishida Y (2000) Seizin zyosei no tayou na raihusutairu to sinriteki well-being ni kansuru kenkyu [Studies on Diverse Lifestyles and Psychological Well-Being in Adult Women]. The Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology 48: 433-443.

- Sawada T (2013) Kankoshi no Well-being to komittomento shokuba no ningen kankei to no kanren-sei [The relationships among occupational and organizational commitment, human relations in the workplace, and well-being in nurses]. Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology 84: 468-476. [crossref]

- Japan Medical Association (2008) Senzai kango shokuin saishugyu shien moderu jigyo hokoku-sho [Report on the 2008 model project to support re-employment of potential nursing staff.] (Retrieved on March 15, 2022)

- Tanaka S, Fuse J (2021) Byouin kinmu no kangosi wo taisyo to sita syokumumanzokudo kenkyu no kadai [Issues in job satisfaction research for nurses working in hospitals]. Journal of North Japan Academy of Nursing Science 24: 1-10.

- Cantril H (1965) The pattern of human concerns. Rutgers University Press.

- Toyoda H, Maeda T, Yanai H (1992) Genin wo saguru toukei-gaku [Statistics to find the cause: Introduction to covariance structure analysis]. Kodansha.

- Oda T (2013) Urutora-bigina no tame no SPSS ni yoru toukei kaiseki nyumon [An introduction to statistical analysis with SPSS for ultra-beginners]. Pleiades Publishing.

- Oshio A (2012) SPSS to Amos ni yoru sinri tyousa deta kaiseki dai 2 han [Psychological and survey data analysis using SPSS and Amos] (2nd ed). Tokyo Tosho.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL (2000) Self-determination theory and the Facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development and well-being. American Psychologist 55: 68-78.

- Boniwell I (2012) Positive psychology in a nutshell: The science of happiness: The science of happiness. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- Kusakari J, Mamada T, Yanagibori R, Oshima Y, Sato ES, et al. (2004). Kango-shoku ― ishi no kyodo to ishi oyobi kangoshoku no shokumu manzokudo to no kanren no kento Aichi ken nai no byoin o taisho to shita chosa no kekka kara [A study of associations between nurse-physician collaboration and their job satisfaction based on a survey at hospitals in Aichi Prefecture]. Bulletin of Aichi Prefectural University School of Nursing & Health 10: 19-25.

a) Shokugyouanteikyoku-Koyouseisakuka/0000200624.pdf

b) (Retrieved on March 15, 2022)